Peter Smith's Blog, page 108

June 17, 2014

Bernays on sets and classes

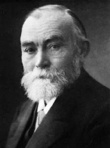

Prompted by his two pieces on Bernays as philosopher, I’ve found myself pausing before reading on in Parsons’s book to step sideways and take a look at Bernays the set-theorist.

I’d not before dipped into Bernays’s little 1958 book Axiomatic Set Theory (long available as a Dover reprint). This gives a first introduction to the kind of set theory Bernays had developed in that long series of papers ‘A System of Axiomatic Set Theory’ published in seven instalments in the JSL between 1937 and 1954 (a promised second volume elaborating on further issues from those papers never appeared).

What we get here is, of course, a set theory with classes as well as sets. Careless classroom talk can make this style of theory seem ad hoc or a pointless cheat. So I was struck by Bernays’s lucid explanation here — albeit in slightly fractured English — of what is going on. In summary,

Th[e] distinction between sets and classes is not a mere artifice but has its interpretation by the distinction between a set as a collection, which is a mathematical thing, and a class as an extension of a predicate, which in comparison with the mathematical things has the character of an ideal object. This point of view suggests also to regard the realm of classes not as a fixed domain of individuals but as an open universe, and the rules we shall give for class formation need not to be regarded as limiting the possible formations but as fixing a minimum of admitted processes for class formation.

In our system we bring to appear this conception of an open universe of classes, in distinction from the fixed domain of sets, by shaping the formalism of classes in a constructive way, even to the extent of avoiding at all bound class variables, whereas with regard to sets we apply the usual predicate calculus. So in our system the existential axiomatic method is joined with a constructive formalism.

By avoiding bound class variables we have also the effect that the class formation

is automatically predicative, i.e. not including a reference by a quantifier to the realm of classes … Further the conception of classes as ideal objects in distinction from the sets as proper individuals comes to appear in our system by the failing of a primitive equality relation between classes. (pp. 56-57)

And so on. There’s helpful elucidation in the last two appendices of Michael Potter’s Set Theory and its Philosophy. But I wish I’d known Bernays’s own presentation a long time ago!

June 16, 2014

Pavel Haas Qt play Smetena 2nd Qt

The Pavel Haas, playing Smetena’s 2nd Quartet live on the BBC, starting about 36 minutes into this programme.

June 14, 2014

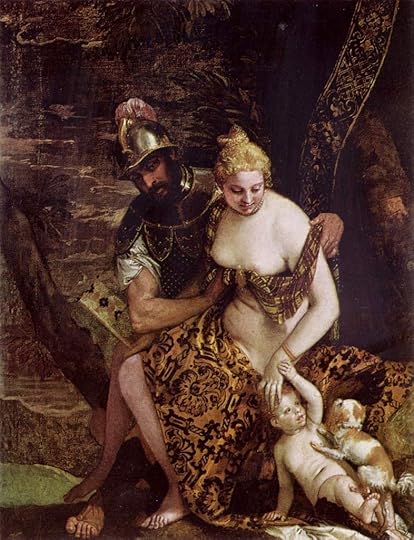

Veronese again

We went to the Veronese exhibition at the National Gallery just after it opened, and were quite bowled over. So we revisited it yesterday, and are more than glad we did so. It was a particular delight to see again the portraits of Iseppo da Porto and his wife Livia, he with a protective arm round their oldest son, she with one of their daughters who is still looking at us quizzically across four and a half centuries (click to enlarge). Now Livia lives on in Baltimore, and Iseppo is in the Contini Bonacossi Collection you can visit one day a week in Florence. But the works belong together — they are not just wonderfully executed but also make a quite extraordinarily humane and very touching pair.

By the datings in the catalogue, Veronese was just 24 when he painted the da Porto portraits in 1552. Which is surely remarkable. And below, painted near the end of his life some 30 years later, is another of our favourites, Venus, Mars and Cupid (from the Scottish National Gallery). Bolder, so richly coloured, but yet for gods at play still rather touchingly human.

Some huge altarpieces, teeming with life and movement, had been allowed to travel from Italy, and the National displayed them very dramatically. By using some of large galleries upstairs (rather than the smaller rooms in the basement of the Sainsbury Wing usually used for special exhibitions), we were allowed vistas through one room to another to see pictures framed by great doorways. The whole exhibition was a triumph (and so it was a surprise that we could just walk in without booking or even queuing, two days before it closed).

So yes, sorry, if you haven’t seen it, and can’t be in London tomorrow, you have missed your chance (the exhibition closes on June 15th). But I can warmly recommend the catalogue as a typically fine piece of book-production by the Gallery (the text is more historical than art-critical, but none the worse for that). The paperback seems to be sold-out at the moment, but the hardback is still something of a bargain. And is full of delights such as this …

Parsons #3: Bernays (continued)

We noted a couple of the most familiar early papers by Bernays, and picked out a prominent theme – a kind of anti-foundationalism (as Parsons labels it). Perhaps we can give finitary arithmetic some distinctive kind of justification (in intuition? in ‘formal abstraction’?), but classical infinitary mathematics can’t receive and doesn’t need more justification than the fact of its success in applications — assuming it is consistent, of course, but (at least pre-Gödel) we might hope that that consistency can be finitarily checked. And for a second theme, we remarked that while Bernays endorses classical modes of reasoning — if not across the board, then in core analysis and set theory — he is not a crude platonist as far as ontology goes: if anything there is a hint of some kind of structuralism.

The anti-foundationalism and hint of structuralism are exactly the themes which are picked up in Parsons’s paper ‘Paul Bernays’ later philosophy of mathematics’.

In discussing the a priori in a number of places, the later Bernays certainly “distance[s] himself from the idea of an a priori evident foundation of mathematics” (to quote Parsons); rather in “the abstract fields of mathematics and logic … thought formations are not determined purely a priori but grow out of a kind of intellectual experimentation” (to quote Bernays himself). But what does this mean, exactly? Bernays proves elusive, says Parsons, when we try to discern more of how he views the “intellectual experience” which is involved in the growth of mathematics. Still,

There’s no doubt that [Bernays] continued to accept what has been called default realism … which amounts to taking the language of classical mathematics at fact value and accepting what was been proved by standard methods as true. … In fact a broadly realist attitude was part of his general approach to knowledge in the post-war years. In one description of the common position of the group around Gonseth [including Bernays], he emphasizes that the position is one of trust in our cognitive faculties. He also introduces the French term connaisance de fait; the idea is that one should in epistemology take as one’s point of departure the fact of knowledge in established branches of science. The stance is similar to the naturalism of later philosophers, though closer to that of Penelope Maddy … than to that of Quine.

True, at least from the evidence Parsons provides, Bernays’s proto-naturalism remains rather schematic (in the end, negatively defined, perhaps, by the varieties of foundationalism he is against). But the theme will strike many as a promising one.

As for the structuralist theme, Parsons says that Bernays “in later writings … took important steps towards working it out.” On the evidence presented here, this is rather generous. Certainly Parsons finds no hint of the key thought, characteristic of later structuralisms, that mathematical objects have no more of a nature than is fixed by their basic relationships in a structure to which they belong. What we do get is a discussion of mathematical existence questions, proposing that these typically concern existence-relative-to-a-structure (an idea that might seem much more familiar now than it would have done when Bernays was writing). Still that can’t be the end for the story since, as Bernays recognises, there remain questions about the existence of structures themselves. According to him, with those latter questions

We finally reach the point at which we make reference to a theoretical framework. It is a thought-system that involves a kind of methodological attitude: in the final analysis, the mathematical existence posits relate to this thought-system.

But then, Parsons says, “Bernays is not as explicit as one would wish as to what this framework might be”, though Bernays seems to think that there are different framework options. There are hints elsewhere too of views that might come close to Carnap’s. But then Parsons also doubts that Bernays would endorse any suggestion that choice of framework is merely pragmatic (and indeed, that surely wouldn’t chime too well with the naturalism). So where are we left? I’m not sure!

“I have claimed,” says Parsons, “some genuine philosophical contributions, but their extent might be disappointing, given the amount Bernays wrote.” Still, Bernays comes across as an honest philosophical enquirer striking off down what were at the time less-travelled paths, paths that many more would now say lead in at least promising directions. So I remain duly impressed.

June 11, 2014

Parsons #2: Bernays

I guess for many – most? – of us, our initial acquaintance with Paul Bernays as a philosopher of mathematics was via his 1934 lecture ‘On platonism in mathematics’ reprinted in the Benacerraf and Putnam collection Philosophy of Mathematics. In retrospect, the important point (insight?) in that lecture is that what is characteristic of what Bernays calls “platonistically inspired mathematical conceptions” is not primarily an ontological view — not the idea of “postulating the existence of a world of ideal objects” (whatever that comes to) — but rather a preparedness to use “certain ways of reasoning”. He has in mind a willingness to apply the law of excluded middle, to apply classical logic in quantifying over infinite domains, to adopt choice principles (appealing to the existence of functions we can’t give a rule for specifying), and the like. And different domains may call for different principles of reasoning: platonism isn’t an all-or-nothing doctrine, but rather we should aim to bring about “an adaption of method” suitable to whatever it is we are investigating.

If we have met Bernays the philosopher again later, then — apart from a rather fleeting appearance in the van Heijenoort volume — it may well be through the translations in Mancosu’s extremely useful 1998 volume From Brouwer to Hilbert which includes four pieces by Bernays. The longest of these is a somewhat earlier essay from 1930 on “The philosophy of mathematics and Hilbert’s proof theory”. Here, he starts by reviewing changing views of what mathematics is about, concluding (at least as at a first pass) that

We have established formal abstraction as the defining characteristic of the mathematical mode of knowledge, that is, focusing on the structural side of objects …

So note that the junior but more philosophically sensitive member of Team Hilbert seems here to be, if anything, hinting at a proto-structuralism as far as ontology is concerned. Bernays then reflects, however, on the fact that formal abstraction from the experienced world doesn’t get us to the (actual) infinite which classical analysis presupposes. What to do? Accept the intuitionist critique of the actual infinite? The price is too high. Turn to the logicists and try to secure the infinite by translating analysis into a purely logical framework? This doesn’t do the desired work, given the problematic role of the axiom of infinity and the even more problematic axiom of reducibility.

We “postulat[e] assumptions for the construction of analysis and set theory” based on supposed analogies between finite and infinite cases. These analogies however don’t by themselves show that “the mathematical idea-formation on which the edifice of [analysis] rests” is in good order. But no matter. The resulting edifice turns out to prove its worth in a spectacular way by its systematic success:

As a comprehensive conceptual apparatus for theory-formation in the natural sciences, [analysis] turns out to be not only suitable for the formulation and development of laws, but it is also invoked with great success, to a degree earlier undreamt of, in the search for laws.

Is that enough? We’d like in addition a consistency proof to confirm that there are no so-far-hidden problems lurking. But note, it is not being said that a proof of consistency “suffices as a justification for this idea formation”: the main justification comes from mathematical and scientific success – so the epistemology is, if anything, “naturalist”. Still, Bernays concludes his 1930 paper as you’d now expect, explaining how the process of rigorous axiomatization makes mathematical theories themselves available as finite objects which can can be studied by finitary modes of reasoning and (we hope, pre-Gödel) shown to be not just spectacularly successful but comfortingly consistent.

Re-reading these two papers, I am struck by how congenial the take-home messages are: and note, by the way, that there is no hint here of the naive, strawman, formalism that Hilbertians used to get accused of. Ok, the ideas are not worked through as thoroughly (or always as clearly) as we would now want: but Bernays’s philosophical inclinations seem to be going very much in the right direction, by my lights anyway. So it could be very interesting to have more of his philosophical work made available by being collected together and translated into English. And yes, just such a project is under way: a volume Paul Bernays: Essays on the philosophy of mathematics edited by Wilfried Sief and others has been announced as in preparation and to be published by Open Court.

Charles Parsons has a long-standing interest in Bernays: indeed he was the translator of that lecture on Platonism for the Benaceraff and Putnam volume, and he has had a role in preparing the Essays volume. And Bernays now makes two extended appearances in Parsons’s own essays in Philosophy of Mathematics in the Twentieth Century. The first is in the longish, previously unpublished, opening piece in the book, ‘The Kantian legacy in twentieth-century foundations of mathematics’. This paper in fact discusses Brouwer, at some length, and Hilbert more briskly, as well as Bernays. But despite Parsons’s efforts, Brouwer’s philosophy remains as murky as ever; and the residual Kantian themes in Hilbert’s “articulation of the finitary method” have been explored before. So the interesting news from this opening piece is perhaps going to be found, if anywhere, in the treatment of Bernays.

Now, as with Hilbert, if there is a Kantian residue in Bernays’s philosophical work, we’d expect to find it in his account of the nature of finitary reasoning and its respects in which it is “intuitive”. And as Parsons remarks, Bernays is actually not very explicit about this: indeed, “I have not found any place where Bernays gives what might count as an ‘official’ explanation of the concept of intuition”. And Parsons later remarks that Bernays e.g. “seems quite unworried” about how we get our knowledge that however far we go along the number series, we can always continue one more step.

There is a hint of admonition here, that Bernays ought to be worrying about these things. But perhaps the dialectical situation is such that these aren’t really his problem. After all, the Hilbertian hopes to work with (a rather restricted portion of) whatever the intuitionist or predicativist or other critic of infinitistic mathematics will allow, and show that those agreed materials are enough in fact to show the consistency of classical analysis. It is the critic, then, who needs e.g. a defence-in-depth of claims about the special “intuitive” status of the agreed materials which he wants to contrast with the infinitary excesses of classical analysis: it is the critic who might have a problem about whether his stringent epistemological principles allow him even to know that we can always continue one more step along the number series. The Hilbertian need only say, e.g., “the kind of finitary reasoning that I am using in my proof theory counts as intuitive by your standards (in so far as I understand them), so you at least can’t complain about that“.

Be that as it may, the discussion of Bernays in the ‘Kantian legacy’ paper is perhaps not very exciting. So let’s now turn to the third piece in Parsons’s book, a substantial paper on ‘Paul Bernays’s later philosophy of mathematics’.

To be continued …

June 4, 2014

Aberystwyth sunset

Old College, Aberystwyth, at sunset

The Guardian has published its latest rankings of UK universities. These things mustn’t be taken too seriously, of course. But I see that Aberystwyth, where I taught for the first half my career, has now plummeted from 50th overall three years ago to 106th (out of 116). And it isn’t just the Guardian which perceives a rapid falling off: the Complete University Guide has Aber dropping over the same period from 47th to 87th. Those are, surely, huge drops, signalling something pretty dire going on. And apparently, applications are dropping sharply too, with the number of new undergraduate students at the university dwindling from 3,283 in 2011 to just 2,510 in 2013, and entry requirements for some courses hitting rock bottom. (There’s now an online petition with some excoriating comments about the current vice-chancellor who, incidentally, got nearly a 10% “performance-related” pay rise for presiding over the first two years of this plunge down the ratings, and now earns 50% more than the Prime Minister …)

When I was in Aber, there were some very distinguished people scattered round the college. My colleagues in the philosophy department included D.O. Thomas, who wrote the definitive book on Richard Price, the Berkeley scholar Ian Tipton, and O. R. Jones – all extraordinarily nice men, and thoughtful serious philosophers (and very hard-working and productive too, by the standards of the day). We had some very good students too: for example, Sue Mendus started as a student the year I arrived there. A department very ripe for closure, then, as happened in the “Thatcher cuts” of the later 1980s. At that time, the institution faced hard choices but seemed to jump the wrong way repeatedly, and the slow diminution as a serious place started that has now accelerated alarmingly. I do wonder what would have happened if Aber had gone down the route of turning itself into a liberal arts college of a quite distinctive kind (which was a rather natural direction to go) …

Aber was the founding college of what became the University of Wales (a national institution which also no longer exists in its original form). It is sad to see the place, which used to be held in quite unusual but very understandable affection by its students, in such precipitous decline.

June 1, 2014

M.M. McCabe: the crisis of the universities

Talking together, talking to ourselves: Socrates and the crisis of the universities.

Here Prof. McCabe says with passion and eloquence and learning what many of us think and sometimes, so much more stumblingly, try to express. Three cheers!

I hope that she makes available a written version of this valedictory lecture for those — normally including me — who, if only for time reasons, don’t get round to watching lectures online. But yes, as Richard Baron says in his comment, the live performance in this case carries an impact that indeed makes it more than worth watching.

Ah, “impact” …

May 30, 2014

Parsons #1: Predicativity

As I’ve said before, I’m planning to post over the coming weeks some thoughts on the essays (re)published in Charles Parsons’s Philosophy of Mathematics in the Twentieth Century (Harvard UP). I’m going to be reviewing the collection of Mind, and promising to comment here is a good way of making myself read through the book reasonably carefully. Whether this is actually going to be a rewarding exercise — for me as writer and/or you as reader — is as yet an open question: here’s hoping!

This kind of book must be a dying form. More and more, we put pre-prints, or at least late versions, of published papers on our websites (and with the drive to make research open-access, this will surely quickly become the almost universal norm). So in the future, what will be added by printing the readily-available papers together in book form? Perhaps, as in the present collection, the author can add a few afterthoughts in the form of postscripts, and write a preface drawing together some themes. But publishers will probably, and very reasonably, think that that’s very rarely going to be enough to make it worth printing the selected papers. Still, I am glad to have this collection. For Parsons doesn’t have pre-prints on his web page, the original essays were published in very widely scattered places, and a number of them are unfamiliar to me so it is good to have the spur to (re)read them. And I should add the volume is rather beautifully produced. So let’s make a start. For reasons I’ll explain in the next set of comments, I’ll begin with the second essay in the book, on predicativity.

Famously, Parsons and Feferman have disagreed about whether there is a sense in which there is an element of impredicativity even in arithmetic. Thus Parsons has argued for “The Impredicativity of Induction” in his well-known 1992 paper. And Feferman (writing with Hellman) explores what he calls “Predicative Foundations of Arithmetic”, in a couple of equally well-known papers, the second of which is in fact in the festschrift for Parsons published in 200o, edited by Sher and Tiezsen. Now the second essay in the present collection is in turn reprinted from Parsons’s contribution to the Feferman festschrift published a couple of years later, edited by Sieg and others. He again returns to issues about predicativity; but perhaps rather regrettably he doesn’t continue the substantive debate with Feferman but instead offers an historical piece “Realism and the Debate on Impredicativity, 1917-1944.” What can we get out of this?

As a preliminary warm-up, let’s remind ourselves of a familiar line about predicativism (the kind of thing we tell — or at least, which I used to tell — students by way of a first introduction). We start by noting the Russellian term of art: a de�finition is said to be impredicative if it de�fines an entity E by means of a quanti�cation over a domain of entities which includes E itself. Frege’s de�finition of the property natural number is, for example, plainly impredicative in this sense. But so too it seems are more workaday mathematical definitions, as e.g. when we define a supremum by quantifying over some objects including that very one.

Now: Poincar�é, and Russell following him, famously thought that impredicative definitions are as bad as more straightforwardly circular defi�nitions. Such de�finitions, they suppose, off�end against a principle banning viciously circular defi�nitions. But are they right? Or are impredicative de�nitions harmless?

Well, Ramsey (and G�ödel after him) famously noted that some impredicative definitions are surely quite unproblematic. Ramsey’s example: picking out someone, by a Russellian defi�nite description, as the tallest man in the room is picking him out by means of a quantifi�cation over the people in the room who include that very man, the tallest man. And where on earth is the harm in that? And the definition of a supremum, say, seems to be exactly on a par.

Surely, there no lurking problem at all in the case of the tallest man. In this case, the men in the room are there anyway, independently of our picking any one of them out. So what’s to stop us identifying one of them by appealing to his special status in the plurality of them? There is nothing logically or ontologically weird going on. Likewise, if we think that, say, the real numbers are there anyway, picking out one of them by its special status as the supremum of a set of numbers is surely again harmless.

It is similar – to continue the familiar story – for other contexts where we take a realist stance, at least to the extent of supposing that reality already in some sense supplies us with a �fixed totality of the entities to quantify over. If the entities in question are (as I put it before) ‘there anyway’, what harm can there be in picking out one of them by using a description that quanti�fies over some domain which includes that very thing?

Things are surely otherwise, however, if we are dealing with some domain with respect to which we take a less realist attitude. For example, there’s a line of thought which runs through Poincar�é, through the French analysts (especially Borel, Baire, and Lebesgue), and is particularly developed by Weyl in his Das Kontinuum: the thought, at its most radical, is that mathematics should concern itself only with objects which can be defi�ned. As the constructivist mathematician Errett Bishop later puts it

A set [for example] is not an entity which has an ideal existence. A set exists only when it has been de�fined.

On this line of thought, defi�ning e.g. a set (giving a predicate for which it is the extension) is — so to speak — defi�ning it into existence. And from this point of view, impredicative defi�nitions involving set quanti�fication can indeed be problematic. For the defi�nitist thought suggests a hierarchical picture. We de�fine some things; we can then defi�ne more things in terms of those; and then defi�ne more things in terms of those; and we can keep on going on (though how far?). But what we can’t do is defi�ne something into existence by impredicatively invoking a whole domain of things already including the very thing we are trying to de�fine. That indeed would be going round in a vicious circle. [Strictly speaking, that's not a reason to ban impredicative definitions entirely: but we will have to restrict ourselves to using such definitions to pick out in a new way something from among things that we have already harmlessly defined predicatively at an earlier stage.]

So much then for at least part of a familiar story (part of the conventional wisdom?). On the one side, the idea is that worries about impredicativity were/are generated by a constructivist/definitist view of some mathematical domain (and are indeed quite reasonable on such a view); on the other side, we have some view which takes the things in the relevant domain to be suitably ‘there anyway’ and so can insist that it is harmless to pin down one them by means of a quantification over all of them including that one.

Now, enter Parsons at the beginning of his paper:

There is a conventional wisdom, to which I myself have subscribed in some published remarks, that the defense of impredicativity in classical mathematics rests on a realist or platonist conception. Such a view is fostered by Gödel’s famous discussion of Russell’s vicious circle principle. Still, I want to argue that this conventional wisdom is to some degree oversimplified, both as a story about the history and as a substantive view. I don’t think it even entirely does justice to Gödel.

On reflection, at some level this got to be partly right. If the attack on impredicativity is generated by constructivist/definitist views, then the defence just needs to resist going down a constructivist or definitist road. And there is clear water between (A) resisting some form of constructivism strong enough to make predicativism compelling, and (B) defending a view that is realist or platonist in some interestingly strong sense.

That’s because one way of doing (A) without doing (B) would be just to resist the whole old-school game of looking for extra-mathematical, ‘foundational’, ideas against which mathematical practice needs to be judged. Mathematicians should just go about their business, without worrying whether it is warranted – from the outside, so to speak — by this or that conception of the enterprise. Just lay down clear axioms — e.g. for the reals, as it might be — and adopt a clear deductive framework and that’s enough: doing this “is logically completely free of objections, and it only remains undecided …whether the axioms don’t perhaps lead to contradiction”. To be sure, a (relative) consistency proof would be nice if we can get it, but that’s just mathematical cross-checking: we don’t need external validation by some philosophically motivated constructivist standards or by realist standards either. Thus, of course, the modern “naturalist” about mathematics. But we can read Hilbert (from whom the quote comes) this way — and Bernays too, who gave a very early lecture commenting on Weyl. So yes, as Parsons nicely explains, from the very outset one line of defence against predicativist attack was (not to substitute a realist for a constructivist philosophical underpinning of mathematics but) in effect to resist the pressure to play a certain foundationalist game. The paradoxes call us to do mathematics better, more rigorously, not to get bogged down in panicky revisionism. Or so a story goes.

However, Weyl in his predicativist phase, or other philosophically motivated mathematical revisionists like the intuitionists (including Weyl in a later phase) will presumably complain that this riposte is thumpingly point-missing. And again, those like Feferman who don’t go the whole hog, but still find considerable significance in the project of seeing how far we can get using predicative theories because they minimize ontological and proof-theoretic baggage, will presumably also want to resist a Hilbertian refusal (if that’s what it is) to engage with any reflections about the conceptual motivations of various proof-procedures. And given Parsons’s own philosophical temperament (as evinced e.g. by his well-known interest in how far you can get one the basis of something like Kantian ‘intuition’), you would have thought that here at any rate he would side with Feferman.

So yes, in remarking that the Hilbertians opposed Weyl without being platonists, Parsons has a real point against the familiar story that sets up too easy an binary opposition between predicativists and realists. But does he want to occupy the further ground thus marked out and be a refusenik about the role of a certain kind of conceptual reflection in justifying proof procedures? Well, see the first comment from Daniel Nagase below, and my note in reply!

Let’s turn now briefly to Parsons’s remarks on Gödel. Gödel undoubtedly wanted to do (A) and he did, famously, come to endorse (B), taking a strongly platonist stance – or so it seems, though what this really comes too is difficult to get straight about.

Now, Parsons urges that we need to distinguish a platonism about objects (the objects of the relevant domain are ‘there anyway’ as I put it, or ‘independent of definitions and constructions’ as Parsons puts it) and a platonism about truth (truth concerning the domain in question is ‘independent of our knowledge, perhaps even of our possibilities of knowledge’ as Parsons puts it). Gödel at first blush accepted both strands in platonism, in some form. Parsons then remarks that only the first strand seems to be involved in the rejection of predicativism, which Gödel takes to be rooted in the opposing idea that the entities involved are “constructed by ourselves”. But I’m not sure how exciting or novel it is to point that out, at least if this isn’t accompanied with rather more discussion about what platonism about a domain of objects really comes to, once supposedly distinguished from platonism about truth. (I say “supposedly” because it isn’t so clear on further reflection that we can elucidate what it is for e.g. numbers to be ‘there anyway’ except via the claim that certain truths that purport to refer to and quantify over numbers are true, where their truth is sufficiently independent of knowledge).

I found Parsons’s discussion here, which is quite brief, a bit unclear. But then, to put it baldly, the realist idea of objects being ‘there anyway’ remains pretty opaque, and Parsons really doesn’t help us out much in this essay (fair enough, it is a relatively modest length historically focused piece). In fact, speaking for myself, rather than appeal to such an idea in order to try to ground accepting predicative definitions over various domains, I’d be tempted to put it the other way about. I’d rather say: accepting the legitimacy of impredicative definitions over a domain constitutes one kind of realism about that domain. Understood that way, ‘realism’ at least has a tolerably clear shape. But then, thus understood, realism can hardly be a ground for accepting impredicativity, as the conventional wisdom would have it. So then, where do we go for arguments?

This wireless world

May 24, 2014

Charles Parsons’s new book — let’s discuss it (again)!

OK, I’m back from Cornwall (and very nice it was too, thanks for asking), and am trying to get the philosophical corner of my mind back into gear. Now, as I mentioned a couple of posts ago, Charles Parsons has published a new collection of some of his essays, Philosophy of Mathematics in the Twentieth Century, which (sensibly or otherwise) I’ve said I’ll review for Mind. So — on the principle that telling people you are going to do something is a good way of keeping yourself up to the mark — I said that I’ll start posting some comments here as I read through the essays. So I better make a start on the reading. Please do chime with and thoughts and comments of your own.

If you want to be reading along, now I’ve had a first skim through the beginning of the book, here’s the plan for the first few instalments. For my opening effort — which I’ll post at the end of the week — I’ll look at Parsons’s second essay ‘Realism and the Debate on Impredicativity, 1917-1944′ (originally published in the Feferman festschrift edited by Sieg et al.).

Parsons’s first essay, new to the present volume, is on ‘The Kantian Legacy in Twentieth-Century Foundations of Mathematics’, and perhaps the most interesting bit of this not-very-exciting essay is on Bernays, so it seems a good notion to discuss that alongside the third essay ‘Paul Bernays’ Later Philosophy of Mathematics’ (published in Dimitracopoulos et al., eds, Logic Colloquium 2005).

Then for my third instalment I’ll look at Parsons’s next two pieces, a short piece on Gödel from the Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers, and then the substantial piece on Gödel’s essay ‘Russell’s Mathematical Logic’ written as an Introductory Note for Gödel’s Collected Works, Vol. II.

So watch this space!