Peter Smith's Blog, page 107

July 31, 2014

Hilbert’s Foundations/Logic Lectures

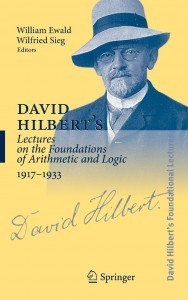

I’ve just been spending a couple of days looking at the massive volume of David Hilbert’s Lectures on the Foundations of Arithmetic and Logic 1917-1933, edited by William Ewald and Wilfried Sieg (Springer 2013), which has at last arrived in the library here.

I’ve just been spending a couple of days looking at the massive volume of David Hilbert’s Lectures on the Foundations of Arithmetic and Logic 1917-1933, edited by William Ewald and Wilfried Sieg (Springer 2013), which has at last arrived in the library here.

The original material is all in German, and since my grasp of the language is non-existent, what I have been reading is in fact the general editorial introduction, and the introductions to the various chapters of book covering different lecture courses and supplementary material (like Bernays’s Habilitationsschrift published here for the first time). There’s a lot of other editorial apparatus (the whole project seems to have been done to an extremely high standard), but the discursive introductions themselves amount to upwards of 130 pages. These are extraordinarily interesting and illuminating even if you can’t (or simply don’t) read the texts they are introducing. True, some of the material in these introductions overlaps heavily with Sieg’s essays already published in his Hilbert’s Programs and Beyond, but it is all still well worth reading (again).

I take it that few people by now cleave to the old myth — propagated e.g. by Ramsey — that Hilbert was a gung-ho naive (or even not-so naive) formalist. But that myth (already surely fatally damaged by Sieg and others) should be well and truly buried by the publication of these various lecture notes which witness Hilbert’s explorations and developing positions over the 1920s.

Let me just remark on two things that struck me, not about the development of Hilbert’s program(s) and the search for consistency proofs but about his contribution to the modern logic. First, it is now clear that the wonderful book by Hilbert and Ackermann published in 1928 isn’t the fruit of a decade’s intensive work after Hilbert’s 1917 return to thinking hard about foundational matters. Rather, the early sections of that book are based very closely on notes for a 1920 lecture course ‘Logik-Kalkül’ prepared by Bernays, and then the core of the book is equally closely based on Bernays’s notes for a 1917/1918 course ‘Prinzipien der Mathematik’. (Ackermann’s contribution to the substantive content of the book indeed seems to have been markedly less than that of Bernays). So suddenly, within seven years of the first volume of Principia (which seems now to belong to a remote era), Hilbert has the makings of a logic text of a recognisable form can still be read with profit. That really is an astonishing achievement.

But second, there are more key ideas about logic in those early lectures which are left out of the book. Thus, in the 1920 lectures, the editors tell us

The logical calculus seems to have been designed to present propositional and first-order logic in a purely rule-based form which allows logical calculations to be presented as they naturally arise within a mathematical proof, and thus to furnish an analysis of logical inference and of the activity of mathematical reasoning.

This aspect of Hilbert’s logical investigations is lost from view in the later book Hilbert and Ackermann 1928 , where the rule-based version of quantificational logic is omitted altogether, and where the canonical versions of both sentential and first-order logic are presented axiomatically. But in these lectures the goal is to obtain a more direct representation of mathematical thought. In the 1922/23 lectures, Hilbert would formulate a calculus that presents, axiomatically, the elimination and introduction rules for the propositional connectives. Here, in early 1920, … Hilbert describes his rules for quantificational logic as ‘defining’ or ‘giving the meaning’ of the quantifiers. (pp. 279-80)

So here then already are intimations of ideas that Bernays’s student Gentzen would bring to maturity a dozen years later. Remarkable indeed.

July 29, 2014

Cutting the TYL Guide down to size

The Teach Yourself Logic Guide was getting rather ridiculously bloated — 138 pages in the previous version. Oops. That was getting distinctly out of hand. I was losing sight of the originally intended purpose of the Guide.

Time to re-boot the project!

So there’s now a new version of the Guide available that weighs in at a much trimmer 78 pages (OK, that probably still sounds a lot, but the layout involves small pages and largish print for on-screen reading, and the first quarter is very relaxed pre-amble). Some of the now deleted material has been re-packaged as supplementary webpages. So I hope that the resulting Guide looks a lot less daunting both in size and coverage. It should certainly be easier to maintain, having divided the core Guide from the supplements which can be updated separately.

The Guide and the add-ons can be accessed here. Spread the word to your students (or if you are a student yourself, I do hope you find something useful here).

July 24, 2014

Category theory in two sentences

Tom Leinster’s book Basic Category Theory arrived today on the new book shelves at the CUP bookshop. I just love the opening two sentences, which seem about as good a minimal sketch of what category theory is up to as you could hope for:

Category theory takes a bird’s eye view of mathematics. From high in the sky, details become invisible, but we can spot patterns that were impossible to detect from ground level.

That’s a brilliantly promising start: and thirty pages in, the book is still proving a really good, if moderately taxing, read.

July 20, 2014

Parsons #5: Gödel on analyticity

The delay in getting round to talking about the next couple of papers in Charles Parsons’s Philosophy of Mathematics in the Twentieth Century signals, I’m afraid, a certain waning enthusiasm. I’m still hopeful that the essays in Part II of the book, on his contemporaries, will prove more exciting, but I found the two pieces on Gödel that end Part I of the collection rather frustrating. Though perhaps the problem is more with Gödel as a philosopher rather than with Parsons. Gödel’s more general remarks — e.g. about platonism, or the role of intuition in mathematical knowledge — too often seem un-worked-out (to put it charitably), and Parsons is too careful a philosopher to leap to giving readings which attribute to Gödel a more developed (and hence more interesting) position than the texts really warrant. So we are left, after reading Parsons’s discussions, not much clearer about what Gödel’s position comes to than we were before.

We’ll look at Parsons’s familiar piece on Gödel’s Platonism in the next post. But first comes ‘Quine and Gödel on Analyticity’, written for a 1995 volume of essays on Quine, but in fact concentrating on Gödel.

The initial theme is that there are some similarities between what Quine and Gödel say about analyticity and mathematics that arise from their shared opposition to the views they attribute to Carnap. Both argue against the view that arithmetic, say, can be held to be empty of content (in Tractarian spirit) by noting that in developing that view, the contentual truth of arithmetic must be already be presupposed in arguing that arithmetic, as a syntactic system, has the properties required of it. (In his Postscript to the reprinted paper, Parsons revisits the question of the force of Gödel’s arguments against the real Carnap.)

But Gödel of course goes on to make a claim that Quine would strongly resist: namely that, while e.g. arithmetic is not analytic in the sense of vacuously-true-by-definition, it is analytic in the sense that (as Parsons puts it) “mathematical truths are true by virtue of the relations of the concepts denoted or expressed by their predicates”.

The trouble is that on the face of it Gödel doesn’t have anything much by way of a theory of concepts, or any very helpful way of explicating his talk of “perceiving” a relationship between concepts except from some opaque remarks about intuition. Or so it will seem to the inexpert reader of the relevant passages in Gödel. And Parsons, as our expert reader, doesn’t seem to find much to help us out here, but rather confirms first impressions that Gödel lacks a serious theory. Which isn’t to say that Gödel must be barking up the wrong tree. Indeed, in the Postscript, Parsons goes as far as to say that “a view something like Gödel’s on this point [that mathematics is in a sense analytic] has always seemed to be the default position”, being something that developed out of his experience as a mathematician, and — which Parsons implies — should chime with the experience of other mathematicians. And I’m tempted to agree with Parsons here. But he too doesn’t do much to hint at how we might develop that view. Which leaves the reader – or at least, leaves this reader – not much further forward.

July 6, 2014

Pavel Haas Qt play the opening movement of Smetena’s 1st Qt.

Sinfini Music have just posted a decent quality video of the Pavel Haas Quartet playing the opening movement of the first Smetena String Quartet, “From My Life”, with their usual intensity.

Apparently, they have now recorded both the Smetena quartets, and the CD will be released by Supraphon early next year. It should be utterly outstanding – certainly, their live performances of both that I have heard have been so.

July 4, 2014

Three requests/suggestions

The Teach Yourself Logic reading guide to logic textbooks, aimed at beginning grad students or thereabouts, is now at version 10.1, 136 exciting pages, and a real snip at zero pounds, zero dollars, and zero anything else. The latest version (and yes, I know it’s time for another update) has a stable URL at http://www.logicmatters.net/tyl/ – students do keep saying that they find it pretty helpful, so why not check that it is mentioned in the relevant logic course handouts?

LaTeX (not just) for Logicians has been going for about 10 years – gulp! – and covers everything you’d expect plus some. It seems more relevant to more grad students than ever, given the popularity of using LaTeX (or close variants). I still tinker with it when I stumble across worthwhile additions (and please do let me know about anything I should add). This too has a stable URL, http://www.latexforlogicians.net which really ought to feature in the relevant info pack or on-line resource webpages for graduate students. Again, worth checking whether it is appropriately linked?

July 3, 2014

Not that smart …

An exhortation, repeated with approval on various philosophy blogs: “We’re all smart. Distinguish yourself by being kind.”

I’m all for being kind, and hope that — when I was in the business — I mostly was (and of course regret the times I knowingly wasn’t). But if you didn’t realize it before, then one thing you would learn by editing a philosophy journal, as I did for a dozen years (reading every submission that Analysis received in that time), is just how many philosophers aren’t smart. Honest plodders, no doubt: but quite capable of sending off for publication dull-witted, uncomprehending, point-missing, or thumpingly fallacious offerings. And we are just kidding ourselves if we suppose otherwise.

Of course, there’s a lot of public bullshit about this, for understandable and not wholly disreputable reasons. We rate each other’s works as “world-class” to help colleagues get grants; we rate someone as outstanding to aid accelerated promotion so that they get paid a tolerable wage. But that doesn’t mean that we really are outstanding, or world-class, or smart.

Mathematicians aren’t under much illusion about this sort of thing. Some are smart, and get to prove important stuff. Others plod, tinkering at the margins. (I was brought up in that hard school, and in part left it because I didn’t think that continuing to be a plodding mathematician was likely to be as much fun as becoming a plodding philosopher).

And it surely isn’t really very different for philosophers, is it? Extra kindness is called for exactly because quite a few of us lots of the time, and no doubt all of us some of the time, aren’t smart — and it hurts to have it rubbed in.

July 1, 2014

Recommending two recent CD releases

CDs take up room, even if they are not as space-hungry as books (sigh! — it must be time for another trip to Oxfam to offload more never-to-be-read-again philosophy books: but that’s a story for another day). Still, despite running out of shelving, I can’t quite bring myself to just buy mp3s or whatever. So there is a little pile of new acquisitions physically sitting there beside me. I’ll mention only two the moment, with warm recommendations for both (not that I’m not sticking my neck out here — I’m just adding my voice to a wider chorus of approval).

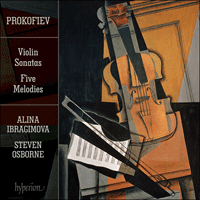

The most recent purchase is Alina Ibragimova’s new recording with Steven Osborne of Prokofiev’s two Violin Sonatas, and the Five Melodies op. 35. Their live performances together have received wonderful reviews (here, for example), and this CD is indeed very fine indeed.  Initially, as you start listening, the piano seems to be recorded surprisingly far forward. But do persevere: this balance is evidently very much intended, and leads to some wonderful effects as Ibragimova’s violin weaves around the piano line — sometimes like `wind in a graveyard’, as Prokofiev told Oistrakh he wanted. (On a second hearing, the balance indeed sounds just right.) Rather to my surprise, I found I didn’t know this music at all — I say a surprise, as once upon a time I used to listen to a lot of Prokofiev (that dates me to the time when Supraphon, with its wonderful list of recordings of Russian and Czech composers, was one of the very few sources of inexpensive LPs, and I then got quite a few). This is another deeply impressive disk from Ibragimova: I’m rather a fan.

Initially, as you start listening, the piano seems to be recorded surprisingly far forward. But do persevere: this balance is evidently very much intended, and leads to some wonderful effects as Ibragimova’s violin weaves around the piano line — sometimes like `wind in a graveyard’, as Prokofiev told Oistrakh he wanted. (On a second hearing, the balance indeed sounds just right.) Rather to my surprise, I found I didn’t know this music at all — I say a surprise, as once upon a time I used to listen to a lot of Prokofiev (that dates me to the time when Supraphon, with its wonderful list of recordings of Russian and Czech composers, was one of the very few sources of inexpensive LPs, and I then got quite a few). This is another deeply impressive disk from Ibragimova: I’m rather a fan.

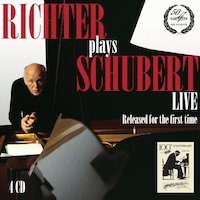

Continuing the Russian theme, I have also recently got the new (and not very expensive) 4CD set of live recordings of Richter playing Schubert in 1978 and 1979 – seven sonatas on the first three discs, and assorted Impromptus, Moments Musicaux, Ländler etc. on the fourth.  It is difficult to keep track of Richter’s recorded legacy, but these performances haven’t been released before. And they are mostly remarkably well recorded, with only occasionally intrusive audience noise. The highlights include a performance of the G major sonata, D 894, slightly less extreme in its handling of the first movement than the (in)famous London recording a decade later, and a really wonderful performance of the first of the last three sonatas, D. 958 (Richter never recorded D. 959, and D. 960 doesn’t feature here). Even if you have other versions of Richter’s Schubert (sometimes wayward, yes, but always compelling), you will surely want this set. For the price of a single concert ticket, one of the greatest Schubertians in his prime.

It is difficult to keep track of Richter’s recorded legacy, but these performances haven’t been released before. And they are mostly remarkably well recorded, with only occasionally intrusive audience noise. The highlights include a performance of the G major sonata, D 894, slightly less extreme in its handling of the first movement than the (in)famous London recording a decade later, and a really wonderful performance of the first of the last three sonatas, D. 958 (Richter never recorded D. 959, and D. 960 doesn’t feature here). Even if you have other versions of Richter’s Schubert (sometimes wayward, yes, but always compelling), you will surely want this set. For the price of a single concert ticket, one of the greatest Schubertians in his prime.

Recommending a couple of recent CDs

CDs take up room, even if they are not as space-hungry as books (sigh! — it must be time for another trip to Oxfam to offload more never-to-be-read-again philosophy books: but that’s a story for another day). Still, despite running out of shelving, I can’t quite bring myself to just buy mp3s or whatever. So there is a little pile of new acquisitions physically sitting there beside me. I’ll mention only two the moment, with warm recommendations for both.

The most recent purchase is Alina Ibragimova’s new recording with Steven Osborne of Prokofiev’s two Violin Sonatas, and the Five Melodies op. 35. Their live performances together have received wonderful reviews (here, for example), and this CD is indeed very fine.  (Initially, as you start listening, the piano seems to be recorded rather too far forward: but do persevere – this balance is evidently very much intended, and leads to some wonderful effects as Ibragimova’s violin weaves around the piano line. On a second hearing, everything indeed sounds just right.) Rather to my surprise, I found I didn’t know this music at all — I say a surprise, as once upon a time I used to listen to a lot of Prokofiev (that dates me to the time when Supraphon, with its wonderful list of recordings of Russian and Czech composers, was one of the very few sources of inexpensive LPs, and I then got quite a few). This is another deeply impressive disk from Ibragimova: I’m rather a fan.

(Initially, as you start listening, the piano seems to be recorded rather too far forward: but do persevere – this balance is evidently very much intended, and leads to some wonderful effects as Ibragimova’s violin weaves around the piano line. On a second hearing, everything indeed sounds just right.) Rather to my surprise, I found I didn’t know this music at all — I say a surprise, as once upon a time I used to listen to a lot of Prokofiev (that dates me to the time when Supraphon, with its wonderful list of recordings of Russian and Czech composers, was one of the very few sources of inexpensive LPs, and I then got quite a few). This is another deeply impressive disk from Ibragimova: I’m rather a fan.

Continuing the Russian theme, I have also recently got the new (and not very expensive) 4CD set of live recordings of Richter playing Schubert in 1978 and 1979 – seven sonatas on the first three discs, and assorted Impromptus, Moments Musicaux, Ländler etc. on the fourth.  It is difficult to keep track of Richter’s recorded legacy, but these performances haven’t been released before. And they are mostly remarkably well recorded, with only occasionally intrusive audience noise. The highlights include a performance of the G major sonata, D 894, slightly less extreme in its handling of the first movement than the (in)famous London recording a decade later, and a really wonderful performance of the first of the last three sonatas, D. 958 (Richter never recorded D. 959, and D. 960 doesn’t feature here). Even if you have other versions of Richter’s Schubert (sometimes wayward, yes, but always compelling), you will surely want this set. For the price of a single concert ticket, one of the greatest Schubertians at his best.

It is difficult to keep track of Richter’s recorded legacy, but these performances haven’t been released before. And they are mostly remarkably well recorded, with only occasionally intrusive audience noise. The highlights include a performance of the G major sonata, D 894, slightly less extreme in its handling of the first movement than the (in)famous London recording a decade later, and a really wonderful performance of the first of the last three sonatas, D. 958 (Richter never recorded D. 959, and D. 960 doesn’t feature here). Even if you have other versions of Richter’s Schubert (sometimes wayward, yes, but always compelling), you will surely want this set. For the price of a single concert ticket, one of the greatest Schubertians at his best.

June 23, 2014

Parsons #4: Gödel

There are four pieces on Kurt Gödel in Parsons’s Philosophy of Mathematics in the Twentieth Century. The first is just ten pages long, and is an encyclopaedia-style entry on Gödel from the 2005 Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers. It seems to me an entirely admirable piece of its kind, though surely rather misplaced in a book whose other chapters are addressed to a significantly more knowledgeable and sophisticated reader.

The second piece is a reprint of Parsons’s introduction to the paper ‘Russell’s Mathematical Logic’ in Gödel’s Collected Works, Vol. II. Again, but for different reasons, this perhaps doesn’t sit entirely comfortably in this collection, for to get the most out of it, you really need to have Gödel’s paper in front of you – in which case you probably already have Parsons’s introduction to hand too. And I do wonder if Parsons has missed a trick here. His introduction in its originally published version very likely had to conform to quite severe space-constraints, and the most interesting sections are hard going because rather compressed. I suspect Parsons had a fair bit more to say, so a more expansive re-presentation of some of the most interesting material would have been a very welcome bonus. In particular, it would have been good if the section on the theory of types – the toughest bit of the paper — could have been reworked at a more leisurely pace.

The topic of one interesting part of the paper — the last main section, on Gödel’s views on whether the axioms of Principia are “analytic” in some sense — does, however, get revisited at much greater length in the third of Parsons’s discussions of Gödel. So I’ll say no more here about Parsons’s first two Gödel essays (this is indeed an insubstantial blogpost!) and instead turn speedily to the essay “Quine and Gödel on Analyticity”.