Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 726

June 15, 2015

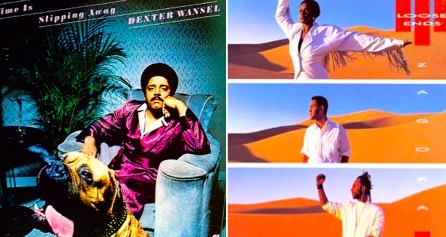

Soul vs. Soul: "The Sweetest Pain"--Dexter Wansel + Loose Ends

Dexter Wansel was like the genius child at Philly International, bringing Afrofuturism into the mix with albums like the classic Life on Mars (1976) featuring tracks like "Together Once Again" and the surrealist "One Millions Miles from the Ground." Though he contributed production to many a Philly Soul hit, his own hist were scarce. Yet "The Sweetest Pain" with Jean Carne from Time is Slipping Away (1979) found its way across the Atlantic to Loose Ends, who covered the track on their second US release Zagora (1986).

Dexter Wansel was like the genius child at Philly International, bringing Afrofuturism into the mix with albums like the classic Life on Mars (1976) featuring tracks like "Together Once Again" and the surrealist "One Millions Miles from the Ground." Though he contributed production to many a Philly Soul hit, his own hist were scarce. Yet "The Sweetest Pain" with Jean Carne from Time is Slipping Away (1979) found its way across the Atlantic to Loose Ends, who covered the track on their second US release Zagora (1986).

Published on June 15, 2015 17:39

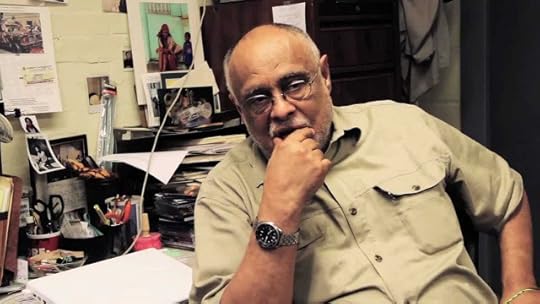

Reel Black: Filmmaker Hale Gerima on Black Imagination + the 21st Century Plantation

In part two of his conversation with ReelBlack, filmmaker and Howard University Professor Haile Gerima talks about the current state of Black Popular Culture and the need for people of color to have equity in their creations. Support Haile's Indiegogo campaign by following @YetutLijMovie #ChildOf on twitter.

In part two of his conversation with ReelBlack, filmmaker and Howard University Professor Haile Gerima talks about the current state of Black Popular Culture and the need for people of color to have equity in their creations. Support Haile's Indiegogo campaign by following @YetutLijMovie #ChildOf on twitter.

Published on June 15, 2015 17:18

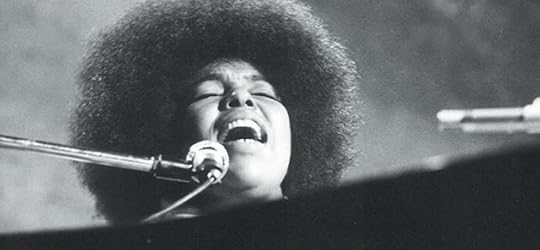

But the Mystery, like the Melody, Still Lingers on . . .: on Roberta Flack

But the Mystery, like the Melody, Still Lingers on . . .: on Roberta Flackby I. Augustus Durham | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

But the Mystery, like the Melody, Still Lingers on . . .: on Roberta Flackby I. Augustus Durham | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Roberta Flack is, unequivocally, my mother’s favorite artist of all time. Although Maxine gave Roberta to me as her own, I learned of her genius via my own listening. Which is to say perhaps my mother loved Roberta because my mother believed herself to be like Roberta and, through my own maturation, now I equally understand that in this identity of twoness, via Farah Jasmine Griffin, if Roberta somehow was not free, in various and sundry ways, my mother was certainly the mystery.

The Showtime documentary Roberta Flack: Killing Me Softly (if you can, watch it immediately!) resembles a whoisit instead of a whodunit. Flack’s black middle-class upbringing and her confirmation as a child prodigy, her proclivities for high (black) church musicality and the vicissitudes of becoming a classical pianist against the backdrop of a red Jim Crow curtain—these highlights are reminiscent of Maxine: birthed among a landscape of clay made red from bloodshed in a history willfully forgotten, she, at a young age, came to local renown for tickling churches’ ivory; she could play a whole service even if her feet barely touched the pedals.

Like Roberta, she was HBCU bred, Talladega specifically, where her classical skills were honed by majoring in piano, minoring in organ; touring with the College Choir; joining a sorority; and winning Miss Talladega 1976. She too chose teaching music in public schools over more “worldly” fare and eventually found a calling in a space that she loved even if it treated her with malcontent. Maxine loved Roberta because she was Roberta. But what the documentary taught me about my mother was precisely what it taught me about Roberta: I did not really know her.

There is this moment in the hour-long chronicle that brought to mind the beginnings of a dinner conversation, and forthcoming project, taken up by Alexander Weheliye around the (black) voice and labor: Dionne Warwick, who classifies herself (and Roberta!) as a “good girl”, states with relative aplomb regarding vocality, “Roberta is more lyrical, in her approach and her vocal prowess; she has a very, very clear, haunting, and soothing voice. Aretha’ll make you sweat, and Roberta makes you think.” These comments are spliced around a live performance of Flack’s “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face”. (Even when Dionne voices “sweat”, we glimpse a kind of doe-eyed ness . . .)

This Black Music Month, I have been thinking about the significance of me not listening to the radio, ad nauseam, anymore—an action I was born into, having spent many a morning, afternoon, and night in the backseat of my mother’s yellow-green Volvo where sing-alongs to the vehicular soundtrack trained my ear—, as well as what it would mean for me to wrestle with my mother’s voice and labor by way of her favorite musician. I say this because a famous Baptist preacher, one Rev. Dr. William Augustus Jones, Jr., once heard Maxine sing and, as she told it, walked up to her and said that God put sweetness in her voice.

Could I not say the same for Roberta? The clarity of her top range, trumpetic in stature, and the mo’nf’lness of her bottom register, a hull-like quality akin to Aunt Ester as renditioned by Phylicia in Gem (see “I Told Jesus” or “Reverend Lee” for both qualities singularly tracked), are suggestive to me that sweetness has infinite possibility or, better still, is innately fugitive: ever seeking, constantly reaching, for the potential that the voice is, a la Rachelle Ferrell, the first instrument. Que cuando cantamos como Angelitos Negros in the collective, it should be orchestral—lift every voice and sing! Considering both women’s mastery of the percussive instrument, perhaps in their primes, they sounded like pianos.

But the mystery, like the melody, still lingers on . . .

The documentation of Flack smoking cigarettes while songwriting with Eugene McDaniels, or her first marriage to her white bassist while thematizing, without proper recognition in many ways still, the late Civil Rights Movement as it transformed to the Black Consciousness/Power/is Beautiful Movement, requires that I reflect on Maxine’s own machinations around process and the ways in which what she produced, whether her creativity or her progeny, always took precedence over the easiest of ways out, no different than Roberta. Maybe it is that what I did not know about Roberta, she taught me through her music, in the same way that I encounter my mother’s love toward me because by gifting me with her music, she gave me her refuge.

To think about all the professorial wisdom Roberta has offered me over the years—that if I were to set my dissertation to music, it would be an EP with “Ballad of the Sad Young Men” as Track 1 on repeat; or that although our song, during happier times, was “Be Real Black for Me”, “Where is the Love” eventuated to be the dirge selected at the interment; or that if Killing Me Softly charts an ethnomusicological genealogy—a version of soul vs. soul—then Roberta making us think gives rise to Lauryn causing us to head nod—I have to acknowledge the female within, say yes to her: you, my mother, Roberta Flack.

And yet, if we were to prolong this staged competition, perhaps what we find is that the perfectly coiffed, evenly picked afro and the affinity for caftans in prints as wild as the wind may mean that when Maxine, like many other black girls, equally mimicked Roberta’s sartorial choices, we have in fact arrived at a draw, for all we know. Then again, maybe Roberta wins because in this contemporary moment of outrageous aping, why opt to see someone pull the (white) rabbit out of the (black) hat when you have always known what #blackgirlmagic looked like?

Just as one of the twosome now inhabits the turn of the phrase on earth as it is in heaven, Roberta, you are my heaven—praises be!

+++

I. Augustus Durham is a third-year doctoral candidate in English at Duke University. His work focuses on blackness, melancholy and genius.

Published on June 15, 2015 11:28

June 14, 2015

'baartman, beyoncé & me' -- a Film Project by Natalie Bullock Brown

How do the beauty ideals of a white, racist, male dominant culture affect black females? -- baartman, beyoncé, & me will be a 60-minute documentary film that explores the impact of white supremacy, racism, sexism and patriarchy on black female feelings about our beauty and sexuality. Among other issues, the film will look at the origins and lasting nature of the unspoken labels "desireable" - or "f---able" as sociologist and anti-porn activist, Gail Dines, calls it - versus "invisible," that male-dominated culture imposes on women in general, and black women in particular. Click to support

baartman, beyoncé, & me

How do the beauty ideals of a white, racist, male dominant culture affect black females? -- baartman, beyoncé, & me will be a 60-minute documentary film that explores the impact of white supremacy, racism, sexism and patriarchy on black female feelings about our beauty and sexuality. Among other issues, the film will look at the origins and lasting nature of the unspoken labels "desireable" - or "f---able" as sociologist and anti-porn activist, Gail Dines, calls it - versus "invisible," that male-dominated culture imposes on women in general, and black women in particular. Click to support

baartman, beyoncé, & me

Published on June 14, 2015 20:56

New Jersey High School Welcomes Kendrick Lamar for Conversation about 'The Bluest Eye'

Brian Mooney, a New Jersey high school teacher used Kendrick Lamar's To Pimp a Butterfly to teach a unit on Toni Morrison's novel, The Bluest Eye. Lamar found out about it, and decided to stop in for a visit.

Brian Mooney, a New Jersey high school teacher used Kendrick Lamar's To Pimp a Butterfly to teach a unit on Toni Morrison's novel, The Bluest Eye. Lamar found out about it, and decided to stop in for a visit.

Published on June 14, 2015 20:36

ReelBlack: Filmmaker Haile Gerima on Defending One's Imagination

Filmmaker and Howard University Professor Haile Gerima sat down with Reelblack to discuss the Indiegogo campaign to raise funds to make Letut Lij and dropped some jewels of wisdom on why controlling our own stories and building an infrastructure to support them is necessary. Look for more Words Of Wisdom throughout Hailie's Indiegogo Campaign (ends July 1) exclusively on Reelblack TV. Follow @LetutLijMovie and find out more at https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/ye...

Filmmaker and Howard University Professor Haile Gerima sat down with Reelblack to discuss the Indiegogo campaign to raise funds to make Letut Lij and dropped some jewels of wisdom on why controlling our own stories and building an infrastructure to support them is necessary. Look for more Words Of Wisdom throughout Hailie's Indiegogo Campaign (ends July 1) exclusively on Reelblack TV. Follow @LetutLijMovie and find out more at https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/ye...

Published on June 14, 2015 20:15

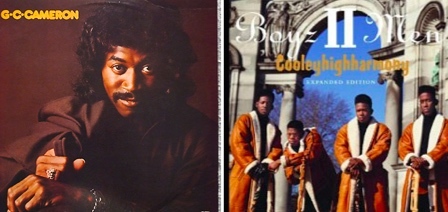

Soul vs. Soul: "It's So Hard to Say Goodbye to Yesterday"--GC Cameron + Boyz II Men

G. C. Cameron is the lead vocalist on

The Spinners'

breakthrough hit "It's a Shame" in 1970 but because of a contractual obligation to Motown, he was unable to remain with the group when they signed to Atlantic in 1972, and began their fabled run of hits with producer Thom Bell. Cameron remains much of a historical sidebar if not for his contribution to the film Cooley High; "It So Hard to Say Goodbye to Yesterday" sonically frames one of the most memorable scenes in the history of Black Cinema. Boyz II Men covered the track and directly referenced the film on their debut album Cooleyhighharmony, and though I am partial to original, thankful to the men from Philly for introducing the song to a new generation.

G. C. Cameron is the lead vocalist on

The Spinners'

breakthrough hit "It's a Shame" in 1970 but because of a contractual obligation to Motown, he was unable to remain with the group when they signed to Atlantic in 1972, and began their fabled run of hits with producer Thom Bell. Cameron remains much of a historical sidebar if not for his contribution to the film Cooley High; "It So Hard to Say Goodbye to Yesterday" sonically frames one of the most memorable scenes in the history of Black Cinema. Boyz II Men covered the track and directly referenced the film on their debut album Cooleyhighharmony, and though I am partial to original, thankful to the men from Philly for introducing the song to a new generation.

Published on June 14, 2015 06:41

June 13, 2015

Rachel Dolezal + the ‘Politics of Passing’: MHP Talks with Allyson Hobbs

Melissa Harris-Perry talks with Stanford Professor

Allyson Hobbs

, author of A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life about the politics of racial passing in light of the Rachel Dolezal case.

Melissa Harris-Perry talks with Stanford Professor

Allyson Hobbs

, author of A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life about the politics of racial passing in light of the Rachel Dolezal case.

Published on June 13, 2015 13:13

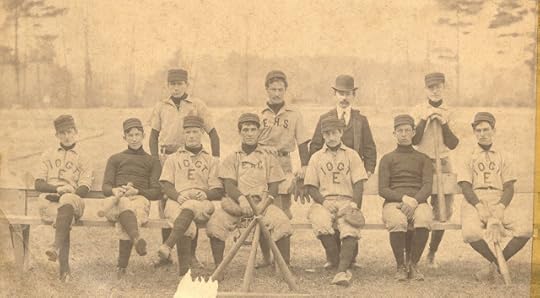

"Just a Friendly Game of Baseball"--Main Source's Classic Metaphor for Police Violence

Main Source's

Breaking Atoms

(1991) is a classic of sample-based Hip-Hop, as well as the album that introduced many to Nasir Jones. More than two decades later, Large Professor's words on "Just a Friendly Game of Baseball"--where America's pastime (Baseball) easily translates into another of this country's pastimes, police violence against Black + Brown bodies--remains prescient and timely.

Main Source's

Breaking Atoms

(1991) is a classic of sample-based Hip-Hop, as well as the album that introduced many to Nasir Jones. More than two decades later, Large Professor's words on "Just a Friendly Game of Baseball"--where America's pastime (Baseball) easily translates into another of this country's pastimes, police violence against Black + Brown bodies--remains prescient and timely.

Published on June 13, 2015 06:20

June 12, 2015

Choosing to be Black? "Space Traders" from Cosmic Slop (dir. Reginald Hudlin)

"Space Traders" was one Derrick Bell's more provocative essays from

Faces at the Bottom of the Well

, raising the ultimate existential question about what it means to be Black--and who gets to choose. The essay was brilliantly turned into a short film, with a screenplay from Trey Ellis and direction from Reginald Hudlin. Piece was part of a three-part one-time-only HBO series called

Cosmic Slop

(from the Funkadelic song).

"Space Traders" was one Derrick Bell's more provocative essays from

Faces at the Bottom of the Well

, raising the ultimate existential question about what it means to be Black--and who gets to choose. The essay was brilliantly turned into a short film, with a screenplay from Trey Ellis and direction from Reginald Hudlin. Piece was part of a three-part one-time-only HBO series called

Cosmic Slop

(from the Funkadelic song).

Published on June 12, 2015 16:42

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.