Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 722

June 27, 2015

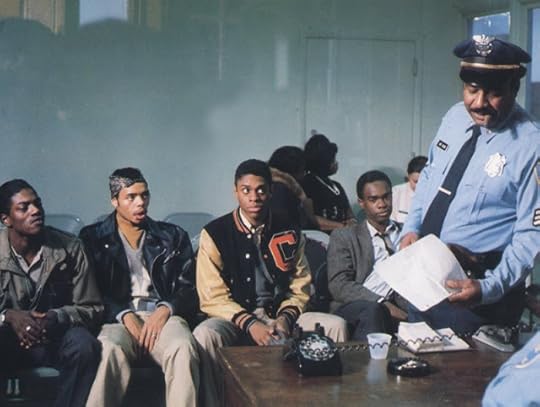

40 Years Later, The Cast Of 'Cooley High' Looks Back

WBEZ 91.5 talks with the cast of Cooley High, on the occasion of the 40th Anniversary of its release. The film, based on a script by Eric Monte and directed by Michael Schultz, starred Glynn Turman and Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs.

WBEZ 91.5 talks with the cast of Cooley High, on the occasion of the 40th Anniversary of its release. The film, based on a script by Eric Monte and directed by Michael Schultz, starred Glynn Turman and Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs.

Published on June 27, 2015 12:41

Bree Newsome Speaking on Art, Activism, Science Fiction and Horror @ Spelman

"Bree Newsome speaks about being an artist & activist and the importance of black science fiction/horror at the Octavia E. Butler Celebration of Arts and Activism, held at Spelman College in April 2014 by author and Spelman Cosby Chair Dr. Tananarive Due. Bree Newsome is a filmmaker whose horror short film Wake won numerous awards."

"Bree Newsome speaks about being an artist & activist and the importance of black science fiction/horror at the Octavia E. Butler Celebration of Arts and Activism, held at Spelman College in April 2014 by author and Spelman Cosby Chair Dr. Tananarive Due. Bree Newsome is a filmmaker whose horror short film Wake won numerous awards."

Published on June 27, 2015 10:21

Whose “Danny Boy”? on An Anthem of Black Loss and Longing by Mark Anthony Neal

Carrie Mae Weems, "Mourning" (2008)Whose “Danny Boy”? on An Anthem of Black Loss and Longingby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Carrie Mae Weems, "Mourning" (2008)Whose “Danny Boy”? on An Anthem of Black Loss and Longingby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)Jackie Wilson seems an unlikely place to think loudly about the matters of Black Lives or even the matters of Black Music. Though less remarked upon than his contemporary, ”the hardest working man in showbiz,” Jackie Wilson was no stranger to working hard. “Mr. Entertainment,” as was Wilson’s moniker (because you had to have one in the 1960s), literally worked himself to death collapsing on stage in 1975; he remained in a semi-comatose state until his death in 1984.

Mr. Wilson’s catalogue includes well known “classic oldies,” such as “Lonely Teardrops” and “(Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher.” This here is no history lesson, but we do take serious Patti LaBelle’s claim in her memoir Don’t Block the Blessings, that Mr. Wilson and a friend tried to rape her. If we are to consider James “Thunder” Early’s point that mid-20th century R&B--Rhythm and Blues--was shorthand for “Rough and Black,” then it’s reasonable to believe that many a Black woman tethered to the economy of the Chitlin’ Circuit were made black and blue. Mr. Wilson is no outlier; even the recent biopic of the “hardest working man in showbiz” admits as much, if only off-screen.

Though Mr. Wilson was from Detroit and Berry Gordy penned some of his early hits, he never recorded for Motown, which has become a catchall phrase for any upbeat, car-happy tracks recorded by African Americans in the 1960s. Ironically a track like Martha and Vandellas’ “Dancing in the Street,” which sonically epitomizes the classic Motown sound, was as much about taking it to the Streets, as it was about Happy Negroes dancing their troubles away.

Mr. Wilson though, was neither upbeat or car happy, when he lent his considerable vocal talents to renditions of the ballad “Danny Boy.” The song was written in 1910 by British songwriter Frederic Weatherly and set to the music of the Irish song “Londonderry Air.” Generally regarded as an anthem of Irish-Americans and often featured at the funerals of law enforcement officers, “Danny Boy” might seem an odd choice for Wilson to record.

Wilson’s connection to “Danny Boy” was personal; it was his first recording under the nickname of Sonny Wilson in 1953, before he replaced Clyde McPhatter as lead singer of The Dominoes. As Susan Whitall writes in her biography of Wilson’s Detroit friend and sometimes nemesis, Little Willie John, “Danny Boy” was a sentimental favorite that was included in both of their repertoires. As Wilson first wife Freda recalls, “He’d always win amateur nights doing “Danny Boy”, and when he recorded it, he did it the same way.” (quoted in Tony Douglas, Jackie Wilson: Lonely Teardrops).

“Danny Boy” was also covered by Sam Cooke and Patti Labelle & The Bluebelles in the period. What is important is that “Danny Boy” was not some novelty song explicitly designed to crossover to White audiences, but was a song that resonated among Black audiences.

“Danny Boy” was Wilson’s signature tune—he often closed his shows with it. As Music critic Don Walker notes in Tony Douglas’ Jackie Wilson: Lonely Teardrops (2005), “By the time Wilson hit the final cadenza in which he wrings 23 – count ‘em – notes out of the word “therefore”, I was convinced there wasn’t a pop singer alive who could stretch such a thin piece of material into the aural equivalent of an Armani suit” (25-26).

I surmise that LaBelle’s own earth-shattering version, recorded with the Bluebelles for the Parkway label in 1962, was at the root of Wilson’s attempt to “discipline” her for jacking his song. This was part of the reality of the Chitlin’ Circuit, where your money was tied to your billing on the marquee; If somebody out-sang you one night, they might appear higher on the marquee the next. But let me make this claim--both Mr. Wilson and Ms. Labelle owned that song, in the way that Black performers have often created an intimacy with pieces of art never intended for their use or consumption. Mr. Wilson and Ms. Labelle transform “Danny Boy” into something that Mr. Weatherly never intended; ain’t nothin’ “Irish Ballad” about the song the way they sing it.

Wilson’s second version appears on Soul Time, an album that finds him in between the successes of the early 1960s and his commercial resurrection in the late 1960s. Released in April of 1965 Soul Time may be one of Wilson’s most accomplished recordings, featuring “Danny Boy” and the opening track “No Pity (in the Naked City).”

“Danny Boy” begins to circulate among Black performance publics during the historical moment in which Paul Robeson re-imagines “Ol Man River”—a song written by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II, and featured in their musical Show Boat (1927), which starred Robeson. As Shana Redmond writes of Robeson’s revisions in the post-World War II period, “Robeson infused the song with the contemporary currents and political of the struggles for civil rights and self-determination in the workplace…‘Ol Man River’ was Robeson’s clarion call in Robeson’s crusade for civil and human rights.” (Anthem: Soul Movements and the Sound of Solidarity in the African Diaspora, 100).

As Redman further notes, per the work of Bernice Johnson Reagon, a significant amount of Black protest anthems from the first half of the 20th century can be described as “adapted songs with a new purpose.” Citing another example from that period, Redmond writes of “We Shall Overcome” that the song “rose to prominence as the anthem the Civil Rights Movement but began its political life as a freedom song in a labor battle on the southeastern seaboard.” (142).

In Wilson’s hands, “Danny Boy” is performed as nothing less than a dirge. Like so many of the hymns that Black Americans transformed into anthems of loss, resistance and resurrection—thinking Alfred E. Brumley's “I’ll Fly Away” or Civilla D. Martin and Charles H. Gabriel’s “His Eye is On the Sparrow” as quick examples—Wilson’s 1965 version “Danny Boy” indexes the immediate losses of his contemporaries Sam Cooke and Malcolm X, the on-going drama that was the Selma campaign, and perhaps the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church.

Incidentally, Patti LaBelle would transform another song—“Somewhere Over the Rainbow”—another sentimental pop song that was recorded by numerous black artists including a young Aretha Franklin. While the song remains in the national consciousness tethered to Judy Garland’s performance of it in The Wizard of Oz, LaBelle has turned it into her signature song that resonates very powerfully among Black LGBTQ communities.

Though “Danny Boy” never rose to the level of national recognition of “We Shall Overcome” or Robeson’s "Ol’ Man River", it was a Friday and Saturday night anthem, for those who most accessible freedoms might be the time they spent at the Apollo Theater in New York or Chicago’s Regal Theater.

And perhaps more importantly, “Danny Boy” highlights the important role that secular Black publics played in the tribute and memorializing of the Black Bodies that mattered in that era, and the Black Bodies that still matter today.

+++

Mark Anthony Neal is Professor of African & African American Studies at Duke University, where he directs the Center for Arts, Digital Culture and Entrepreneurship. He is the author of several books including What the Music Said: Black Popular Music and Black Public Culture, Soul Babies: Black Popular Culture and the Post-Soul Aesthetic, and Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities. Neal hosts the video podcast Left of Black; you can follow him on Twitter at @NewBlackMan.

Published on June 27, 2015 06:53

June 26, 2015

Terence Blanchard + The E Collective Offer Music of Protest with 'Breathless'

With Eric Garner's dying words "I can't breathe," as inspiration, Terence Blanchard's latest release

Breathless

(with The E Collective) musically addresses the realities of Black life in the contemporary moment. The album features cover art from Andrew F. Scott (Black Man Grove: Resilience) and a cover recording of Les McCann and Eddie Harris' "Compared to What?"

With Eric Garner's dying words "I can't breathe," as inspiration, Terence Blanchard's latest release

Breathless

(with The E Collective) musically addresses the realities of Black life in the contemporary moment. The album features cover art from Andrew F. Scott (Black Man Grove: Resilience) and a cover recording of Les McCann and Eddie Harris' "Compared to What?"

Published on June 26, 2015 20:25

Robert Glasper "Covers" Kendrick Lamar's "I'm Dying of Thirst" as Tribute to Black Lives Lost

On Robert Glasper's phenomenal new trio recording Covered, he closes with a cover of Kendrick Lamar's "I'm Dying of Thirst" that serves as a memorial to #BlackLivesLost.

On Robert Glasper's phenomenal new trio recording Covered, he closes with a cover of Kendrick Lamar's "I'm Dying of Thirst" that serves as a memorial to #BlackLivesLost.

Published on June 26, 2015 19:41

Immutable Fictions: on Protected Classes by Karla FC Holloway

Immutable Fictions: on Protected Classesby Karla FC Holloway | @ProfHolloway | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Immutable Fictions: on Protected Classesby Karla FC Holloway | @ProfHolloway | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)The phrase you are looking for, Americans-fascinated-by-the-Dolezal-fabrications, comes from Constitutional Law. It is “protected class.” That’s the legal issue that makes race matter in the “complicated” ways Dolezal insisted were a part of her identity determinations.

Yes. Of course race is an imagined social construction. In fact, race is a “legal fiction,” one that has evolved as a critical accompaniment to our country’s history. The United States has made race matter in ways that make policing its boundaries—who’s in, who’s out—an unpleasant, and sometimes odd necessity. The Supreme Court, the NAACP, scholars of black history and culture, everybody on #BlackTwitter become the hall monitors and bring a variety of membership requirements (or not) to this inevitably contradictory site. It’s historical and it’s not. It’s skin color and it’s not. It’s your mama and it’s not.

But when the proverbial “Miss Ann” slips into racial disguise, the shifting parameters make plain where the problem lies. The essential complication is a legal one. It’s the scaffolding we’ve had to construct alongside our social peculiarities—from slavery, to freedom, to #Ferguson (hashtag intentionally appended). It is through law that protected classes are maintained and established. Dolezal discovered this when she tried to sue HBCU capstone Howard University for discrimination and her suit was dismissed because she was without standing. She was not (then) a part of a constitutionally protected class. Is she today now that she “identifies as Black?” Nope.

Not if the restoration of voting rights legislation, access to federal remedies for discriminatory conduct, or legal review of a host of blatant and shadowed racisms matter. And they do in ways directly tied to our very mortality. #BlackLivesMatter is not just a hashtag. But this critical vulnerability doesn’t matter to Dolezal, who uses her privileged shape-shifting because she feels our pain and is drawn to the spirit of “black is beautiful.” But her willful ignorance of the precarity of race matters in U.S. law, especially given her professional affiliations, is offensive. She seems unconcerned that her race-based stunt will weaken the claims of others when race is just a matter of wanna-be.

I am concerned enough with race as a sustainable legal site to be one of the somebodies who turns her round. Not today Miss Ann. Back away from the house party.

Identities matter in America because we have made them matter. Despite our national imagination regarding race neutrality and the desideratum of post racial bliss, persistent structural discriminations have been necessarily and appropriately addressed through laws that make discriminatory conduct illegal. Federal laws that prohibit discrimination recognize some bodies with identities that are “immutable” in the language of constitutional law.

When Dolezal makes her race mutable, she makes a claim that does harm to the legal protections built on its arguably incoherent but nonetheless legal integrity.

Of course race can be culturally appropriated. There is something extraordinarily possible, flexible, and always in potentia in America that has constructed its special appeal. However, the “you can be anything you want—if you work hard enough…” exists outside of a critical interrogation that notices how harmful racialized conduct makes aspiration contingent.

When Justice O’Connor mused that in twenty-five years we may not need the structures of affirmative action to fix and assure educational equity, she imagined a future when the law would not be sutured to our social fictions. It was a musing some have taken to be a directive and aggressive moves to dismantle affirmative action proceed apace. It was also a musing that limned the edges of racial reasoning that have composed our legal fictions.

As a nation, we are nowhere near a race-neutral society—the resegregation of our schools, the vitality of race inequities in medical outcomes that are attached to medicine’s biases rather than intrinsic patient profiles, employment discrimination, patterns of police conduct and incarceration, the lack of diversity in technology sectors, the shootings in Charleston, these patterns shift with our cultural attainments but still, they are patterns.

Our conversations about race retain their aspirational component. We want to be whoever we think we are even though we express this wistfulness in a society that maintains patterns of discrimination. We are citizens standing in absolute need of legal protections because our conduct is a pattern of repeated racial discriminations. U.S. history and our contemporary social realities make the pairing of race and law necessary. It’s a fiction that has come to need its legal scaffold. Antics like Dolezal’s race-based fantasyland threaten the necessary protections of law.

If she’s so in-sync with black folk, that consequence should matter as much as her racial imagination.

+++

Karla FC Holloway is James B. Duke Professor of English at Duke University, where she also holds appointments in the Law School, Women's Studies, and African & African American Studies. Holloway is the author of BookMarks: Reading in Black and White and Codes of Conduct: Race, Ethics, and the Color of Our Character, as well as Private Bodies, Public Texts: Race, Gender, and a Cultural Bioethics and Passed On: African American Mourning Stories: A Memorial, both published by Duke University Press. Follow her on Twitter at @ProfHolloway.

Published on June 26, 2015 19:20

June 25, 2015

On Charleston: Black Genocide as Rapture by Ahmad Greene-Hayes

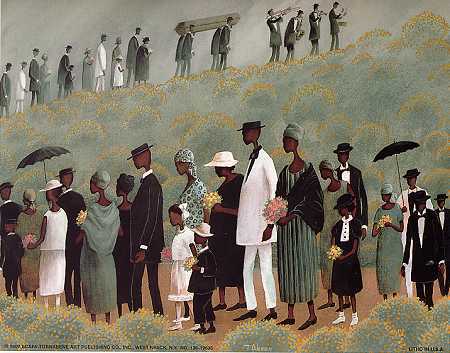

Image Credit: Funeral Procession by T. ColemanOn Charleston: Black Genocide as RaptureAhmad Greene-Hayes | _@BrothaG | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Image Credit: Funeral Procession by T. ColemanOn Charleston: Black Genocide as RaptureAhmad Greene-Hayes | _@BrothaG | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Published in 1992, Derrick Bell’s The Space Traders tells the story of munificent and powerful extraterrestrials offering the United States gold, advanced technology, clean nuclear power and a host of other benefits in exchange for all Black people living in the United States. In many ways Bell’s narrative depicts a long-standing truism in the history of Black life in the American nation-state: the dollar over Black humanity.

One of Bell’s characters, a pro-trade citizen, offered these words: “All Americans are expected to make sacrifices for the good of their country. Black people are no exceptions to this basic obligation of citizenship. Their role may be special, but so is that of many of those who serve. The role that blacks may be called on to play in response to the Space Traders’ offer is, however regrettable, neither immoral nor unconstitutional.” In true sadistic form, Black death, Black suffering, Black grief and Black mourning are the sacrifices that keep the god of white supremacy throned and unbothered. Forgoing commitments to justice or constitutionality, the U.S. government sacrificed Black people for capitalistic gain.

“The inductees looked fearfully behind them. But, on the dunes above the beaches, guns at the ready, stood U.S. guards. There was no escape, no alternative. Heads bowed, arms now linked by slender chains, black people left the New World as their forebears had arrived.”

The imagery of a spaceship taking away all Black people to a far away place likens to “the rapture,” or what some millenarian theologians posit as the snatching of “born-again Christians” off the earth at the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. Rapture theology is informed by popular readings of the Book of Revelation in the Bible, and in many Christian traditions across the globe, it informs believers’ life practices through a psychology of fear. Notions of “Be ye also ready” or “Don’t let [Jesus] catch you with your work undone” permeate the hearts of many. Believers are often led to live out strict spiritual lives in order to be sinless at the point of Christ’s supposed return.

In fact, as a teenager, I remember being shown “Are you ready?” a Youtube.com video of what the rapture may look like. I also remember being shown “Rapture cartoons,” which made rapture theology clear to young children. I also recall being told to read the book of Revelation when I had questions about sex in my teenage Sunday school class.

Today, as a follower of Christ, I’m no longer convinced by rapture theology or the scare tactics that Evangelicals have used to not only manipulate thousands (including myself) but to also make thousands off of “Left Behind” books, sermons, films and lectures (see Barbara R. Rossing’s The Rapture Exposed).

More importantly, as a Black person living in an anti-Black racist society, the safety of rapture is undeniably reserved solely for white Christians. In fact, under white supremacist Christianity, only white people can be saved and safe, because Black people are seen as inherently criminal, diabolical, and monstrous as former Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson opined last year.

In the aftermath of the Charleston Massacre, where nine innocent Black lives were ruthlessly taken, I am left wondering whether the god of white supremacy orchestrates Black people’s rapture from the perilous conditions of an anti-Black world. Note, however, that the rapture that Black people experience is not a peaceful one. In fact, our Savior does not meet us, but instead our rapture is only obtained through bloodshed. This rapture is also directed at Black people—not because we are so “good” as rapture theologians would posit, but rather, because white supremacists do not see us as human.

Our rapture is genocide, and like all genocides, we are snatched away from our communities never to return again. This god feeds off of Black death, and accordingly, Black people are in a perpetual state of rapture. The god of white supremacy must live, even if that means that Black people must perpetually die—socially, psychically, physically, or communally.

To be raptured away in a church during a Wednesday night Bible study would seem logical to many rapture theologians, however, how does one reconcile the grotesque and vicious “snatching away” of Black life—not as spiritual comfort, religious reward or even as a consensual act—but rather, as a sacrifice on the altar of white supremacy? How does one make sense of the multiplicity of ways that Black people are raptured away from their families every single day?

Dylann Roof chose to massacre those nine innocent lives as rapture, but his ancestors and even his comrades today, use a variety of tactics—everything from lynching, rape, bombings, redlining, gentrification and poverty to police brutality, hyperincarceration, and inaccessibility to healthcare.

The god of white supremacy has taken one bite too many from the table of Black communal suffering. Its gluttonous ways render Black life a delicacy to be eaten over and over again. However, in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement, and as the families of the slain lay their loved ones to rest this week, we unapologetically proclaim, “We fired up! Can’t take it no more!”

+++

Ahmad Greene-Hayes is a writer and organizer from New Jersey, discerning a call to ministry and theological study. He is also the creator of #BlackChurchSex and can be followed on Twitter @_BrothaG.

Published on June 25, 2015 14:41

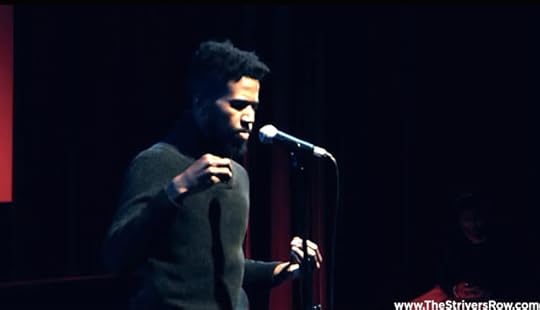

"Still Life With Black Death" -- Spoken Word from Joshua Bennett

Joshua Bennett performs "Still Life With Black Death" at The Strivers Row #BlackLivesMatter Benefit Show. Recorded Live at MIST Harlem, USA.

Joshua Bennett performs "Still Life With Black Death" at The Strivers Row #BlackLivesMatter Benefit Show. Recorded Live at MIST Harlem, USA.

Published on June 25, 2015 14:07

Sun Ra: Astro Black Mythology & Black Resistance (Panel)

Footage from the Sun Ra: Astro Black Mythology & Black Resistance symposium held at the University of Chicago in May of 2015, on the occasion of Sun Ra's 101st birthday. Panelist include Anthony Reed + William Sites + Greg Tate and moderator Will Faber.

Footage from the Sun Ra: Astro Black Mythology & Black Resistance symposium held at the University of Chicago in May of 2015, on the occasion of Sun Ra's 101st birthday. Panelist include Anthony Reed + William Sites + Greg Tate and moderator Will Faber.

Published on June 25, 2015 13:42

June 24, 2015

Digitally Connecting Inmates with Their Children through Books

'A new program uses technology to fill an important role in the development of the children of those who are incarcerated. Organizers say the TeleStory program is the first of its kind in the country. At the main branch of the Brooklyn Public Library in New York, families of inmates bring their children to a special room filled with toys and books. Even more unique: the room is virtually connected to a prison on Rikers Island.'-- Marketplace

'A new program uses technology to fill an important role in the development of the children of those who are incarcerated. Organizers say the TeleStory program is the first of its kind in the country. At the main branch of the Brooklyn Public Library in New York, families of inmates bring their children to a special room filled with toys and books. Even more unique: the room is virtually connected to a prison on Rikers Island.'-- Marketplace

Published on June 24, 2015 20:38

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.