Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 725

June 18, 2015

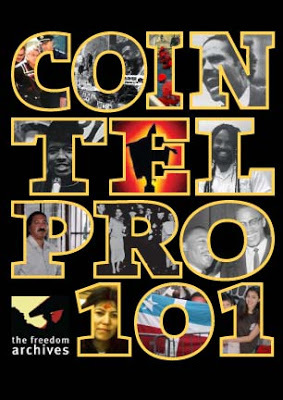

Monthly Film Series “Liberation Sundays” Presents, COINTELPRO 101 (June 28th)

“Liberation Sundays” Monthly Film Series Presents, COINTELPRO 101

On Sunday, June 28th the Durham Branch of Workers World Party in cooperation with Cuban Revolution Restaurant & Bar will be launching the “Liberation Sunday” Film Series, a free monthly event featuring films which highlight people's struggles against exploitation and oppression around the world.

This month's film will be COINTELPRO 101, a short documentary about the FBI's Counter Intelligence Program which repressed numerous social justice movements by means of surveillance, infiltration, imprisonment, frame-ups and even outright assassinations.

Community screenings will be held on the last Sunday of each month beginning at 5:30pm. Each screening will be followed by an open discussion. Complimentary refreshments provided by Cuban Revolution Restaurant and Bar located at 318 Blackwell St., Durham NC. For additional information contact Lamont Lilly at 919.904.8479 or via Twitter @LamontLilly.

Review via Black Agenda Report

“COINTELPRO 101 is an introduction to the often omitted history of the FBI’s illegal wars of terror waged against the full spectrum of radical Left movements in this country. The Counter Intelligence Program which emerged in the post-WWII era of international struggles for human rights and national liberation simply focused internally to the United States all that had been carried out against populations abroad. It turned so-called U.S. citizens in the 20thcentury into insurgent rebels to be dealt with as any foreign army or movement. Assassination, imprisonment, surveillance and encouraged internal strife were employed to forcibly dissolve these movements. But, as this film so skillfully demonstrates, this all was merely an extension of a continuing state project of enslavement, genocide, theft of land, culture and humanity that pre-dates even the official declaration of U.S. nationhood.” ~Jared A. Ball

Documentary Website: http://www.freedomarchives.org/Cointelpro.html

Cuban Revolution: http://www.thecubanrevolution.com/

Meet the Durham Branch of Workers World Party: https://www.facebook.com/DurhamWWP

Published on June 18, 2015 07:36

June 17, 2015

ReelBlack: Halie Gerima on Contented Black Folk and the Importance of Ava DuVernay

Filmmaker and Howard University professor Haile Gerima shares with ReelBlack his thoughts on filmmaker Ava DuVernay, the movie Selma and several recent Hollywood films about Black folks that have grossed over $100 million. Support Haile's new project @LETUTLIJMOVIE #ChildOf on Indiegogo. https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/ye... A Reelblack exclusive.

Filmmaker and Howard University professor Haile Gerima shares with ReelBlack his thoughts on filmmaker Ava DuVernay, the movie Selma and several recent Hollywood films about Black folks that have grossed over $100 million. Support Haile's new project @LETUTLIJMOVIE #ChildOf on Indiegogo. https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/ye... A Reelblack exclusive.

Published on June 17, 2015 19:26

New MOCA Exhibit Celebrates Legacy of Marlon Riggs' 'Tongues Untied'

'The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles, presents Tongues Untied (June 6 - September 13), an exhibition titled after the landmark film by poet, activist, and artist Marlon Riggs. Tongues Untied presents a selection of works from the museum’s permanent collection by John Boskovich, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and others, alongside Riggs’s deeply personal and lyrical exploration of black gay identity in the United States.'

'The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles, presents Tongues Untied (June 6 - September 13), an exhibition titled after the landmark film by poet, activist, and artist Marlon Riggs. Tongues Untied presents a selection of works from the museum’s permanent collection by John Boskovich, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and others, alongside Riggs’s deeply personal and lyrical exploration of black gay identity in the United States.'

Published on June 17, 2015 19:11

#OneWord: Black Men & Boys Ages 5-50 on 'America'

In this latest episode of #OneWord the folk at Cut asked Black men and boys from 5 - 50 to respond to one word: "America."

In this latest episode of #OneWord the folk at Cut asked Black men and boys from 5 - 50 to respond to one word: "America."

Published on June 17, 2015 18:57

"If you want to ride these curves, jump in your Chevy Nova"--Tamia "Sandwich and a Soda"

Published on June 17, 2015 08:41

What Happened to the “Black” in Black Music Month? by Mark Anthony Neal

What Happened to the “Black” in Black Music Month?by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan |

NewBlackMan (in Exile)

What Happened to the “Black” in Black Music Month?by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan |

NewBlackMan (in Exile)

In June of 2009, President Barack Obama proclaimed June as African American Music Appreciation Month. The President’s proclamation came thirty years after then President Jimmy Carter established June as Black Music Month, though it wasn’t made official until the 106th Congress (1999-2000) passed H.Res 509, the so-called African-American Music Bill. The post-racial sleight-of-hand in the re-branding of Black Music Month, made even more explicit with President Obama’s affirmation, highlights the subtle ways that the Black(ness) of Black Music Month has been muted for the more commercially viable African American Music Appreciation Month. What is lost when Black Music Month is no longer “Black”?

As Dyana Williams, often referred to as the “woman behind Black Music Month” recalls, the idea for Black Music Month came in the form of pillow talk with ex-husband, Kenneth Gamble, who with Leon Huff was the architect of Philadelphia International Records (PIR). Gamble was enamoured with the work of the Country Music Association, and through the creation of the Black Music Association and in concert with others like broadcaster Ed Wright and Clarence Avant, who founded Sussex Records (Bill Withers) and later Tabu Records (SOS Band & Alexander O’Neal) helped lobby the Carter administration for some kind of public celebration of the value of Black Music.

In a 2013 interview with The Root, Gamble is honest about his commercial interest in the founding of Black Music Month: “What happens when you have a music month? You get additional marketing dollars, and it helps to market and promote the artists,” also noting that theme for the month was “Black Music is Green.” Indeed, more than 30 years later, Black Music Month, like its more well known step-sibling Black History Month, offers an opportunity for labels to market “Black” music, cable networks like BET and TV One to offer “special” programming and for iTunes to discount its rather considerable digital catalogue. Recall, for example the deluge of “Black” titles that the trade publishers release in the weeks before Black History Month.

To be sure, Gamble was always clear about the connection he saw between commerce and politics; between the record company he co-founded--via a groundbreaking relationship with Clive Davis and Columbia Records--and economic independence. The legacy of Mr. Gamble’s vision is mixed income housing and a charter school in Philadelphia.

But Gamble was also very clear about the political value of the music. Where Berry Gordy, who was both inspiration and competition for Philadelphia International Record, branded his company “The Sound of Young America,” Gamble’s embraced the notion of the “message in the music.” While both men were committed to maintaining the bottom lines of their musical operations, Gamble believed that Black Politics was commercial, often packaging PIR with short essays to reinforce that point.

The Philadelphia International Records catalogue is like a primer into Black consciousness in the 1970s; Billy Paul singing “Am I Black Enough for You?;” The O’Jay’s offering “Don’t Call Me Brother,” Teddy Pendergrass’s sermon at the opening of Harold Melvin & Bluenotes “Be For Real” or the Three Degrees’s cautionary tale about sexual predators, “Dirty Ol’ Man.” I mention these particular songs to contrast the more celebratory songs in the catalogue like The O’Jays “Family Reunion” or The Intruders’ “I’ll Always Love My Mama” to highlight that Gamble and Huff mined both the pleasures and pitfalls of Blackness.

Of course Gamble and Huff were not functioning in a vacuum; PIR was simply making explicit the historical claims of Black Music--Amiri Baraka riffing in the background “The spirits do not descend without music”--and they were not alone. The 1960s and 1970s, represents a unique historical moment when the commercial production of Black music and Black politics were publicly synchronous (it is always privately or non-commercially synchronous), in part because movement was profitable--a point that Robert Weems makes in his book Desegregating the Dollar: African American Consumerism in the Twentieth Century.

The richness of the Black musical moment of the 1960s and 1970s is oft-romanticized, folks sometimes dismissing the structural needs that were met by making Black struggle commerical, bringing both curious White consumers and so called “conscious” Black consumers to the same mainstream marketplace; It was not accidental that television shows like Soul Train and The Jackson 5 cartoon launched nationally in the same era that Berry Gordy produced Lady Sings the Blues, Mahogany and Pippin, Columbia Records bankrolled PIR, or Clive Davis, who sanctioned the Harvard Report that foregrounded the creation of PIR, signed Gil Scott Heron as his first Black artist on his fledgling Arista label. When Black Music Month was created in 1979, the politics of Black Music were implicit.

In many ways PIR’s clear devotion to aspirational, urbane Blackness, ironically became the means in which R&B and Soul music--the foundational music of the Black working class and poor, and the music in which the rank-and-file of Black communities most accessed political critique in music--jettisoned its connection to the everyday realities of Black life. With the massive crossover success of artists with deep roots in R&B like Michael Jackson, Lionel Richie, Whitney Houston, and to some extent Prince--all were marketed as pop artists in the 1980s--traditional R&B groups largely followed suit, pursuing music with more “universal” themes.

Whereas the decade of the 1980s began with albums like Stevie Wonder’s Hotter Than July, where Wonder advocated for a national holiday for Martin Luther King, Jr. and paid tribute to Bob Marley, and Rick James’ Street Songs, which channeled his own days growing up in Buffalo, NY, the decade closed with albums by Babyface, Karyn White, Bobby Brown and Anita Baker. The exceptions at the end of the decade were the Hip-hop recordings that “crossed over” to the R&B charts, which mirror the ways that politics in Black music were shifted to rap music. Save a womanist critique that represented the sonic reflection of the burgeoning industry of popular Black women’s fiction in the late 1980s and 1990s, R&B was largely absent of politics.

Unfortunately the legitimate political critique and social commentary offered by Hip-Hop artists were often undermined by the presumed pathology of Hip-Hop culture and the Black youth that it represented in the mainstream. When rap music itself became more mainstream than R&B, the gutting of political commentary in much of mainstream Black popular music had been made complete, so much so, that even the mention of political ideas and social movement, as is the case recently with recordings from D’Angelo and Kendrick Lamar, elicited wild excitement.

The notion of “African American Music Appreciation Month” speaks to the important contributions that Black artists have made to American culture, but the celebration is largely devoid of the very real political concerns that have always been a formative aspect of Black musical culture in the United States.

While we can applaud the recognition of Black artists who are, in part, the architects of American music, to do so without explicitly naming the role of that music in the very social justice and revolutionary movements that have shaped this nation, is an insult to those musical traditions and those who crafted them.

+++

Mark Anthony Neal (@NewBlackMan) is Professor of African & African American Studies at Duke University, where he also directs the Center for Arts, Digital Culture and Entrepreneurship. Neal is the author of five books including Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities (2013) and Soul Babies: Black Popular Culture and the Post-Soul Aesthetic and the host of the video podcast Left of Black. Neal has been celebrating Black Music Month with the hashtag #BlackMusicMatters.

Published on June 17, 2015 05:13

June 16, 2015

NYC Dominicans Protest Haitian Deportations in the Dominican Republic

'In a powerful show of solidarity Dominican Americans protested at the Dominican consulate in New York City yesterday to say no to deportations of Dominicans of Haitian descent. The community of Dominicans in the diaspora in New York, where the largest population of Dominicans outside of the mainland reside, planned this protest as part of a larger coalition to fight the deportations and anti-Haitian racism that plagues Dominicans and other Caribbean countries as a result of historical and systemic oppression. #BastaYa #BlackLivesMatter #DominicanRepublic #DominicanosPorHaiti #WeAreAllDominican #YoTambienSoyHaiti #Ayiti'--RadicalLatina

'In a powerful show of solidarity Dominican Americans protested at the Dominican consulate in New York City yesterday to say no to deportations of Dominicans of Haitian descent. The community of Dominicans in the diaspora in New York, where the largest population of Dominicans outside of the mainland reside, planned this protest as part of a larger coalition to fight the deportations and anti-Haitian racism that plagues Dominicans and other Caribbean countries as a result of historical and systemic oppression. #BastaYa #BlackLivesMatter #DominicanRepublic #DominicanosPorHaiti #WeAreAllDominican #YoTambienSoyHaiti #Ayiti'--RadicalLatina

Published on June 16, 2015 17:52

The Outing of Rachel Dolezal and American Anxiety with Race by Lee D. Baker

The Outing of Rachel Dolezal and American Anxiety with Raceby Lee D. Baker | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

The Outing of Rachel Dolezal and American Anxiety with Raceby Lee D. Baker | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Rachel Dolezal, former president of the NAACP chapter in Spokane, Washington, resigned Monday amid allegations of lying about her race. The real news story was the social-media firestorm that surrounded her so-called lie that she was of African descent.

Genetically, anthropologically, and biologically, all Homo sapiens are from Africa. Nearly all anthropologists agree with the recent single-origin hypothesis that dates the dispersal of humans out of Africa a mere 60,000 years ago. For the vast majority of time that anatomically modern humans have lived, they lived in Africa.

In the course I teach at Duke University, called “The Anthropology of Race,” I tell my students that any American can check the box “African American,” and be on solid ethical and legal ground.

The “outing” of Rachel Dolezal exposed the collective anxiety Americans have about the racial politics of culture and the cultural politics of race. It was never about a technical discussion about the timing of the out of Africa hypothesis, it exposed the fact that one’s ethnic identity can change over time, that culture is learned (not inherited), and race is social and political, not biological.

In short, race is a social construct that can be produced, manipulated, and even fabricated. Human diversity cannot be sorted into neat racial boxes or discrete racial categories. Ironically, this collective anxiety about the plasticity of race, comes on the heels of the very public transformation of Bruce to Caitlyn Jenner amid unprecedented visibility, understanding, and legislative initiatives empowering transgendered people with more respect and rights.

The tight alignment of race, ethnicity, and culture in the United States is the product of history and politics, preceding the Declaration of Independence, but codified and ratified in that document when Thomas Jefferson penned, “we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” With these words, Jefferson fashioned an explicatory cudgel that many individuals and groups used with mighty force to bludgeon and suppress people by systematically dehumanizing and infantilizing those for whom it was self-evident should have no rights.

Americans have a deep investment in keeping race real, and when there is evidence of the plasticity of race, the perpetrator of this hoodwink gets lambasted, ridiculed, and collectively shamed. Identity is a multifaceted modality that involves the people you love, the language you speak, how you pray, and how you fashion your clothes, hair, and family. If one’s identity is not aligned with one’s heritage, it can still be authentic.

+++

Lee D. Baker is Mrs. A. Hehmeyer Professor of Cultural Anthropology and Dean of Academic Affairs for Trinity College of Arts and Sciences at Duke University. He is author of Anthropology and the Racial Politics of Culture (2010) and From Savage to Negro: Anthropology and the Construction of Race, 1896-1954 (1998)

Published on June 16, 2015 14:41

Traveling Haitian History Through Creole Proverbs

Join Duke University lecturer, Jacques Pierre as he travels through Haiti's history, culture, and geography with playful a second set of riddles or memonèt.

Join Duke University lecturer, Jacques Pierre as he travels through Haiti's history, culture, and geography with playful a second set of riddles or memonèt.

Published on June 16, 2015 10:08

Billy Paul: "Am I Black Enough for You?" (1972)

Published on June 16, 2015 04:47

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.