Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1049

October 29, 2011

Musicians #Occupy Wall Street

?uestlove, Moby, Kweli, Kanye West, Russell Simmons, Bilal, Angelique Kidjo, and Gbenga Akinnagbe (from The Wire) stand in solidarity with the #Occupy protests on Wall Street and across the country.

For more information on how you can help and get involved, check www.okayplayer.com/wallstreet.

Published on October 29, 2011 12:23

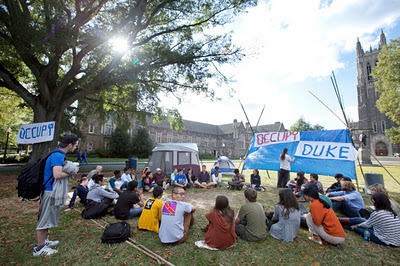

The Occupy Movements and the Universities

The OccupyMovements and the Universities by Mark Naison | Special to NewBlackMan

The Occupation movements spreading around the nationand the world have the potential to revitalize University life,particularly those initiatives involving community activism and thearts.. The role of arts activists in Occupy Wall Street is a storythat has not been fully told,. Community arts organizations in New Yorksuch as the South Bronx's Rebel Diaz Arts Collective and Brooklyn's Global Block Collective have been involved with Occupy Wall Street foralmost a month, making music videos on the site, documenting the movement'sgrowth through film, and trying to bring working class people and people of colureinto the movement. The Occupation has become an essential stopping point for awide variety of performing artists, none of whom have asked for payment fortheir appearances. Universityfaculty and participants in community outreach initiatives can only benefitfrom tapping into this tremendous source of energy and idealism. I have neverseen students on my campus so excited about anything political or artisticas they have about these Occupation movements, which have spread into outerborough New York neighborhoods ( We have had "Occupy the Bronx")as well as cities throughout the nation and the world. What themovement has done is reinvigorate democratic practice- much of it face to face-widely regarded as nearly extinct among young people allegedly atomized bytheir cell phones and iPods.

One my students,a soccer player at Fordham said the following about her experience on a march across the Brooklyn Bridge that led to mass arrests. "Going tothe protest I felt like this was the closest I was going to get to reliving myfather/uncle's young adulthood! While we were stuck on the bridge people werepassing around cigarettes, water, food anything anyone had they shared.Announcements were organized so everyone knew what was going on. People wereyelling were changing the world! THE WOLRD IS WATCHING. I called my father onthe bridge told him I was getting arrested, and I could tell he was proud! Itwas unbelievable". Her sense ofexcitement about the energy and communal spirit at OWN mirrors my own. Eachtime I have been at OWS I have sat in on discussion groups created on topicsranging from Mideast politics, to understanding derivatives, to educationalreform. The discussions I have participated in have been rigorous,political diverse, and to be honest much more vibrant than mostcomparable discussions I have been part of at universities.

Those of uswho work at Universities need to find ways of connecting to a movementwhich has inspired so much creativity and intellectual vitality.. As someonewho has been to many "Occupation" events, ranging from teach ins, to grade ins,to marches, and has spoken about this movement at my own university and toglobal media, I have experienced this energy and vitality first hand. But mostimportant, my STUDENTS have experienced this and it has given them a sense thatthey have the power to make changes in a society which they feared had becomehopelessly stagnant and hierarchical.

Consider theremarks of 2010 Fordham grad Johanne Sterling who works at Fordham's DorothyDay Center for Service and Justice, about what participating in this movementmeant to her, even though the experience got her arrested and sprayed withmace:

"I had plans to attend a peaceful protest on Wall Street. . . I was happy to know that I was offering my voice and my support to a movementI believed in. As a young person in this country, I cannot say that I have notgrown more and more unnerved with the injustices I see every day. The fact thatour government is quietly but surely taking away our democratic rights (Firstwith the Patriot Act, ironically named, and then with new voting restrictionsthat are being put into law), the fact that so many of my fellow graduatescannot find meaningful, rewarding work no matter how hard they try, the factthat our country's infrastructure is falling apart while the richest 1%continue to increase astronomical amounts of wealth, and the fact our justicesystem was able to execute and continue to execute and/or imprison innocentindividuals disproportionately based on their socio-economic position and theirethnicity are simply a few reasons as to why I decided to attend therally." This kind ofcivic consciousness and social justice activism is precisely what so manyprogressive scholars and university based community outreach programshave sought to inspire. It is being brought to life by young people themselvesin this growing national movement.

There are nowover 100 Occupations in cities throughout the nation. They are part of a globalawakening of young people that has caused governments around the world totremble, and financial elites to face the first real challenge to their powerin decades We in the Universities did not create this movement. Butwe ignore it at our peril. It brings to life many things we have been teaching.And it does something that we should be doing, but aren't doing enough- itempowers our students!

***

Mark Naison is a Professor of African-American Studies andHistory at Fordham University and Director of Fordham's Urban Studies Program.He is the author of two books, Communistsin Harlem During the Depression and WhiteBoy: A Memoir. Naison is also co-director of the BronxAfrican American History Project (BAAHP). Research from the BAAHP will bepublished in a forthcoming collection of oral histories Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life From the1930's to the 1960's.[image error]

Published on October 29, 2011 12:04

Putting the "Run Away Slaves" Ahead of the Plantation: Parity, Race and the NBA Lockout

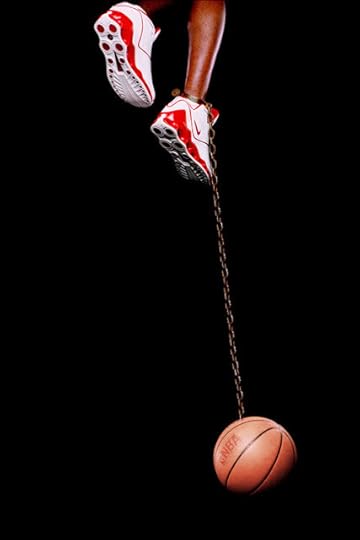

"Basketball and Chain" by Hank Willis Thomas

"Basketball and Chain" by Hank Willis ThomasPutting the "Run Away Slaves" Ahead of thePlantation: Parity, Race and the NBA Lockoutby David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

In wake of LeBron James'decision to take his talents, along with those of Chris Bosh, to South Beach tojoin forces with Dwayne Wade, the NBA punditry has been lamenting the demise ofthe NBA. This only became worsewith the subsequent trades of Deron Williams and Carmelo Anthony to New Jerseyand New York respectfully. Describedas a league "outof control in terms of the normal sports business model" where player power"kills the local enthusiasm for the customer and fan base," wheresuperstars leave smaller markets with no hope of securing a championship,where manipulating players and agents have created a game dominated by "players whose egosare bigger than the game," much has been made about player movement.

Commentators have lamentedhow players are yet again destroying the game from the inside, thinking ofthemselves ahead of its financial security and cultural importance. In "NBA no longer fan-tastic," Rick Reillylaments the changing landscape facing the NBA. Unlike any other sport, the NBA is now a league where "veryrich 20-somethings running the league from the backs of limos," are "colludingso that the best players gang up on the worst. To hell with the Denvers, theClevelands, the Torontos. If you aren't a city with a direct flight to Paris,we're leaving. Go rot." In otherwords, this line of criticism have warned that "theinmates are running the asylum," somuch so that the league "islittle more than a small cartel of powerful teams, driven by the insecuritiesand selfishness of the players who stack them."

While such rhetoric eraseshistory (of trades – players of the golden generation have certainly demandedtrades; the same can be said for other sports as well) and works from a faultypremise that parity is good for the economics of the NBA (the very differenttelevision monies for the NBA and NFL proves the faultiness of this logic), theidea that the league needs more parity remains a prominent justification forthe NBA lockout. "The ownersbelieve that the league should be more competitive and that teams should havean opportunity to make a profit," notes David Stern.Similarly, Adam Silver, deputy commissioner, argues,"Our view is that the current system is broken in that 30 teams are not in aposition to compete for championships."

Such rhetoric and Stern'subiquitous statements about the NBA needing a dramatic restructuring buildsupon argument that the NBA's future is tied to its ability to thwart playerslike LeBron James, Carmelo Anthony, Deron Williams, and potentially DwightHoward, Chris Paul, and others from taking their talents anywhere. The cautionary rhetoric was evident inJason Whitlock's "NBAplayers are wrecking their league:"

This whole NBA scenario — from LeBron's Decision to Melo's Madness toDeron's Escape — reminds me of the American housing bubble. . . .

For close to a decade, NBA players have walked the thin line betweenlove and hate with their customers. The players crossed it when Ron Artest and several Indiana Pacers climbed into the stands to brawl with spectators. Commissioner DavidStern instituted a string of new rules — dress code, tougher restrictionsprohibiting fighting, 19-year-old age requirement for the draft — to push theplayers back on the other side of the line.

Those Band-Aid policies are starting to break. The players, many ofwhom have never grasped the need to understand and satisfy their customer base,are beginning to unwittingly push back.Soaked in the arrogance of fame, wealth, immaturity and businessignorance, the players have dramatically reshaped the league with theirfree-agent and impending free-agent maneuvers.

In doing so — in destroying basketball in Cleveland, Utah and Denver —LeBron, Melo, Amar'e and Deron reinforced the perception among fans that teamsdon't matter.

"As a player, you have to do what's best for you," Wade told reportersin reaction to the Carmelo trade to New York. "You can't think about whatsomeone's going to feel or think on the outside. You have to do what's best foryou, and that's what some players are doing. I'm happy for those players thatfelt that they wanted to be somewhere and they got their wish."

That pretty much sums up the mentality of the modern-day American andmodern-day pro athlete. Pleasing the individual takes precedence overeverything else. It doesn't matter that the collective strength of the NBA madeWade rich. Wade and other NBA players must be concerned only with themselves.That's the American way.

He, like others, has called upon David Stern and the owners to protect theleague, the game, and the players from the players themselves. And that is what we are seeing with theNBA lockout. Yes, it is aboutmoney – yes, it is about free-agency, the mid-level exception, hard versus softcaps, splits in revenue, and countless other issues but in the end thisstruggle is one that is about power and control. It is a struggle to reverse if not end free agency, toguarantee profit and competitiveness (and lower salaries) through limitingplayer movement. It is aboutreversing the victories of pastcollective bargaining agreements and even Curt Flood.

It represents a strugglefrom the owners to make sure the future LeBron James' doesn't have the abilityto take his talents to South Beach; it is a fight to make sure the next wave ofstars doesn't follow in the footsteps of Carmelo and Deron Williams who purportedlyused the mere prospect of free agency to lead to force a trade. It is a fight about restricting thepower of the NBA's 40 million dollar slaves from exercising what little powerthey possess.

While the issues at workcertainly relate to notions of parity, small market versus big market, andcountless other issues, the scorn and rhetoric sounding the alarms plays upon fearsresulted from the increased perceived power of black athletes. The fears, the accusations, and thespeculation as to the demise of the league, all which play on the purportedselfishness, lack of intelligence, egos, and overall attitude of today's(black) players builds upon longstanding stereotypes regarding blackmasculinity. It is the livingembodiment of the infamous words said between two cops regarding Malcolm X:"that's too much power for one man to have." The NBA players, its primarily black players, have exhibitedtoo much power, leading to widespread panics and condemnation; it has led toaction in the form of the NBA lockout.

We can understand the NBAlockout by looking at the work of Herman Gray, who argued that blackness existsas a "marker of internal threats to social stability, cultural morality, andeconomic prosperity." It is similarity evident in the writings of Homi Bhabbiwho persuasively described blackness in the white imagination as "both savage(cannibal) and yet the most obedient and signified of servants (the bearer offood); he is the embodiment of rampant sexuality and yet innocent as a child;he is mystical, primitive, simple-minded and yet the most worldly andaccomplished liar, and manipulator of social forces." The NBA lockoutis justified by the ideas that blackness is "simple-mindedness" that blacknessis childishness, and that blackness is a space of manipulation, all of whichthreatens the long-term success and profitability of the NBA product. The lockout is an effort to get thatunder control, to prevent anymore runaway slavesfrom putting themselves ahead of the plantation, I mean the game.

***

David J. Leonard isAssociate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and RaceStudies at Washington State University, Pullman. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary AfricanAmerican Cinema and the forthcoming AfterArtest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press). Leonard is a regularcontributor to NewBlackMan andblogs @ No Tsuris.[image error]

Published on October 29, 2011 11:28

October 28, 2011

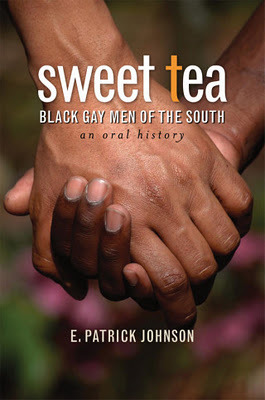

October 31st 'Left of Black' Explores The Experiences of Black Gay Men in the South and the Legacy of 18th Century Poet Phillis Wheatley

November 1st Left of BlackExplores The Experiences of Black Gay Men in the South and the Legacy of 18thCentury Poet Phillis Wheatley

Host and Duke UniversityProfessor Mark Anthony Neal is joinedvia Skype© by E.Patrick Johnson , author of SweetTea: Black Gay Men of the South; an Oral History. A Professor ofPerformance Studies at NorthwesternUniversity, Johnson's ethnographic work on this book evolved into a playcalled Pouring Tea: Black Gay Men of theSouth Tell Their Tales. Johnson shares his motivation to turn hisbook into a play, and also discusses how his journey through these projectshelped him better come to terms with his own personal issues. He shareshis reactions to the different responses he's gotten so far from to the stageperformance. Johnson, whose play premiered in Chicago's About Face Theaterand was recently staged at The Signature Theater in Arlington Virginia, alsodiscusses the significance of the title. Later Neal is joined by HonoreéFannone Jeffers , poet, commentator, satirist, blogger and professor ofEnglish at the University of Oklahoma. Jeffers, author of several collections of poetry including The Gospel of Barbecue and RedClay Suite, discusses her blog Phillis Remastered andher work-in-progress on the 18th century poet Phillis Wheatley. In a wide ranging conversation, Neal and Jeffers also discuss the legacy of AishahShahidah Simmons' groundbreaking film NO! The Rape Documentary, the Slut Walk protests & the conceptof Post-Black.

***

Leftof Black airs at 1:30 p.m. (EST) on Mondays on Duke's Ustream channel: ustream.tv/dukeuniversity.Viewers are invited to participate in a Twitter conversation with Neal andfeatured guests while the show airs using hash tags #LeftofBlack or#dukelive.

Left of Black is recorded and produced at the John Hope Franklin Center of International and InterdisciplinaryStudies at Duke University.

***

FollowLeft of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlackFollowMark Anthony Neal on Twitter: @NewBlackManFollowHonoreéFannone Jeffers: @BlkLibraryGirl

###[image error]

Published on October 28, 2011 05:26

October 27, 2011

Classic Black Cinema | John Akomfrah--The Last Angel of History (Intro)

A 1995 documentary directed by John Akomfrah discussing all things afrofuturistic. Features interviews with George Clinton, Derrick May, Kodwo Eshun, Stephen R. Delany, Nichelle Nichols, Juan Atkins, DJ Spooky, Goldie and many others. The film makes mention to Sun Ra, whose work centers around the return of blacks to outer space in his own Mothership. Produced in 1995.

Published on October 27, 2011 14:16

October 26, 2011

"Right Thru Me": Authenticity, Performance, and the Nicki Minaj Hate

[image error]

"RightThru Me": Authenticity, Performance, and the Nicki Minaj Hateby Javon Johnson | special to NewBlackMan

I began teaching at the University ofSouthern California in fall 2010 as the Visions and Voices Provost'sPostdoctoral Fellow. Among others, one of my duties as Postdoc is to teachAfrican American Popular Culture. One of the biggestdifficulties with teaching a course such as this is the seemingly impossibletask of trying to get my students to move beyond simply labeling aspects of Blackpop culture as good or bad – that is, getting them to unearth and criticallydiscuss the political, social, economic, and historical stakes in Black film,music, theater, dance, literature and other forms of Black popular culture.

I struggled mightily with getting them to see how a Blackartist or sports figure could simultaneously be good and bad and how thoselabels, even when collapsed, do little to explain how violent rap lyrics areused as justification for unfair policing practices in Black communities, howliterature and music is often used as a means for many Black people to enterinto a political arena that historically denied us access, or even how Blackpopular culture illustrates that the U.S., since pre-Civil War chattel slavery,has had, and will continue to have, a perverse preoccupation with Black bodies.

My class is not the only group of people who have troublemoving beyond the ever-limiting dualities of good and bad. Like my students whocould not wait to tell me all of the reasons they feel Nicki Minaj is a badartist, icon, and even person, many Black people that I speak with are quick tothrow the Harajuku Barbie under the bus on account that, as one of my studentsput it, "She makes [Black women] look bad, like all we are good for is ass,hips, and partying." Fellow rappers such as Lil Mama and Pepa have commented onNicki's over-the-top dress up and character voices, with Kid Sister asking, "dopeople take her seriously?" What is most troubling about comments such as theseis how reductive they are, how readily they dismiss Black women's identitypossibilities, in that anyone who dresses and talks like Nicki must be sellingout and doing a disservice to real hip-hop, real Black people, and real women.

The politicsof selling out aside, I am deeply troubled with how we read Lady Gaga as abrilliant postmodern pop artist and Nicki as little more than a fake who playsdress up for cash. What does that say about our understandings of Black womenas related to the politics of respectability? Nicki disserves applause forcarving out a space in an overly male dominated rap world, and, as she did in arecent Vibe.com interview, she often uses that space to tell women and girlsthey "are beautiful…sexy…[and powerful because] they need to be told that." Mixing thezaniness of ODB and Busta Rhymes with lyrical prowess of Lil Wayne and thecreativity of Lil Kim and Andre 3000, all wrapped in a Strangé Grace Jones bow,the fact that Nicki can tell all the men in rap, or perhaps the world for thatmatter, "you can be the king or watch the queen conquer," that is – join me orbe destroyed by me, highlights the strength and boldness she possesses. More than herability to dominate a male driven hip-hop community or the lines promotingwomen's empowerment throughout her work, it is her playfulness, coupled withher perceived sexuality and gender identity that causes the most panic. It isour inability to define and pin down Nicki's identities that scare us most. Hervoices and dress up lead many to question not only if Nicki is "real," thatindefinable quality that permeates every fiber of hip-hop, but also for some toquestion her sexuality. In a hip-hop world where the most valuable currency isauthenticity, the anxiety, or hate for that matter, Nicki causes stem mostlyfrom the fact that she puts front stage all the things most rappers hide behindthe curtains. Her entire persona, which relies on a healthy amount oftheatricality, exposes how the real is as constructed as the reel, which makesher performance shattering because too many of us invest a lot in the idea thathip-hop is undeniable and unapologetic truth. In this way,it is my larger contention that we are reading Nicki Minaj all wrong. Ratherthan figuring her characters, voices, and costumes as faking, I propose that weread it as making, as a performance of multiple reals that exist on the samebody. And, it is quite precisely her Barbie like plasticity, her ability tomold herself into the woman she needs to be at any given moment, which is mostamazing. Nicki's malleability, her ability to be such a monster and such a ladyin the same verse, complicates our understanding of identity performances toaccount for the ways in which people can be dynamic, complex, contradictory,and fractured beings all at once. Whether it is Onika Tanya Miraj, Nicki Minaj, RomanZolanski, or any of her other alter egos, Nicki plays with identity in waysthat would make any scholar of performance proud. And, how real and, moreimportant, brilliant is it for someone who studied theater to use characters intheir career in entertainment? Nicki's vague and playful gender and sexuality performancesstand as constant reminders that identity, never fixed, is always in flux. Thisis not to say that Nicki Minaj is unproblematic. Rather, her dynamicperformances both on and off the hip-hop stage open up spaces for amazing queerand feminist possibilities and they are constant reminders how frequentlyarchaic identity tropes fail in everyday life, and quite honestly we need to bereminded of that on a more regular basis.

I am not asking for the singular real Nicki, instead Iwelcome all of her. The ability to alter one's identity as one wishes ispowerful, after all, it is the stuff that makes up many superhero narratives. Iwonder, however, when we will begin to see this potentially subversivepossibility as less a hindrance and more of an ability.

***

JavonJohnson is currently the Visions & Voices Provost's Postdoctoral Fellow atthe University of Southern California, where he teaches in the Department ofAmerican Studies & Ethnicity. He earned his Ph.D. in Performance Studies,with a cognate in African American Studies and a certificate in Gender Studies,from Northwestern University. He is a back-to-back national poetry slamchampion (2003 & 2004), has appeared on HBO's Def Poetry Jam,BET's Lyric Café, and co-wrote a documentary titled Crossover, whichaired on Showtime, in collaboration with the NBA and Nike. He has written forOur Weekly, Text & Performance Quarterly, and is currently working on hisbook, tentatively titled, Owning Blackness: Poetry Slams and the Making ofSpoken Word Communities.[image error]

"RightThru Me": Authenticity, Performance, and the Nicki Minaj Hateby Javon Johnson | special to NewBlackMan

I began teaching at the University ofSouthern California in fall 2010 as the Visions and Voices Provost'sPostdoctoral Fellow. Among others, one of my duties as Postdoc is to teachAfrican American Popular Culture. One of the biggestdifficulties with teaching a course such as this is the seemingly impossibletask of trying to get my students to move beyond simply labeling aspects of Blackpop culture as good or bad – that is, getting them to unearth and criticallydiscuss the political, social, economic, and historical stakes in Black film,music, theater, dance, literature and other forms of Black popular culture.

I struggled mightily with getting them to see how a Blackartist or sports figure could simultaneously be good and bad and how thoselabels, even when collapsed, do little to explain how violent rap lyrics areused as justification for unfair policing practices in Black communities, howliterature and music is often used as a means for many Black people to enterinto a political arena that historically denied us access, or even how Blackpopular culture illustrates that the U.S., since pre-Civil War chattel slavery,has had, and will continue to have, a perverse preoccupation with Black bodies.

My class is not the only group of people who have troublemoving beyond the ever-limiting dualities of good and bad. Like my students whocould not wait to tell me all of the reasons they feel Nicki Minaj is a badartist, icon, and even person, many Black people that I speak with are quick tothrow the Harajuku Barbie under the bus on account that, as one of my studentsput it, "She makes [Black women] look bad, like all we are good for is ass,hips, and partying." Fellow rappers such as Lil Mama and Pepa have commented onNicki's over-the-top dress up and character voices, with Kid Sister asking, "dopeople take her seriously?" What is most troubling about comments such as theseis how reductive they are, how readily they dismiss Black women's identitypossibilities, in that anyone who dresses and talks like Nicki must be sellingout and doing a disservice to real hip-hop, real Black people, and real women.

The politicsof selling out aside, I am deeply troubled with how we read Lady Gaga as abrilliant postmodern pop artist and Nicki as little more than a fake who playsdress up for cash. What does that say about our understandings of Black womenas related to the politics of respectability? Nicki disserves applause forcarving out a space in an overly male dominated rap world, and, as she did in arecent Vibe.com interview, she often uses that space to tell women and girlsthey "are beautiful…sexy…[and powerful because] they need to be told that." Mixing thezaniness of ODB and Busta Rhymes with lyrical prowess of Lil Wayne and thecreativity of Lil Kim and Andre 3000, all wrapped in a Strangé Grace Jones bow,the fact that Nicki can tell all the men in rap, or perhaps the world for thatmatter, "you can be the king or watch the queen conquer," that is – join me orbe destroyed by me, highlights the strength and boldness she possesses. More than herability to dominate a male driven hip-hop community or the lines promotingwomen's empowerment throughout her work, it is her playfulness, coupled withher perceived sexuality and gender identity that causes the most panic. It isour inability to define and pin down Nicki's identities that scare us most. Hervoices and dress up lead many to question not only if Nicki is "real," thatindefinable quality that permeates every fiber of hip-hop, but also for some toquestion her sexuality. In a hip-hop world where the most valuable currency isauthenticity, the anxiety, or hate for that matter, Nicki causes stem mostlyfrom the fact that she puts front stage all the things most rappers hide behindthe curtains. Her entire persona, which relies on a healthy amount oftheatricality, exposes how the real is as constructed as the reel, which makesher performance shattering because too many of us invest a lot in the idea thathip-hop is undeniable and unapologetic truth. In this way,it is my larger contention that we are reading Nicki Minaj all wrong. Ratherthan figuring her characters, voices, and costumes as faking, I propose that weread it as making, as a performance of multiple reals that exist on the samebody. And, it is quite precisely her Barbie like plasticity, her ability tomold herself into the woman she needs to be at any given moment, which is mostamazing. Nicki's malleability, her ability to be such a monster and such a ladyin the same verse, complicates our understanding of identity performances toaccount for the ways in which people can be dynamic, complex, contradictory,and fractured beings all at once. Whether it is Onika Tanya Miraj, Nicki Minaj, RomanZolanski, or any of her other alter egos, Nicki plays with identity in waysthat would make any scholar of performance proud. And, how real and, moreimportant, brilliant is it for someone who studied theater to use characters intheir career in entertainment? Nicki's vague and playful gender and sexuality performancesstand as constant reminders that identity, never fixed, is always in flux. Thisis not to say that Nicki Minaj is unproblematic. Rather, her dynamicperformances both on and off the hip-hop stage open up spaces for amazing queerand feminist possibilities and they are constant reminders how frequentlyarchaic identity tropes fail in everyday life, and quite honestly we need to bereminded of that on a more regular basis.

I am not asking for the singular real Nicki, instead Iwelcome all of her. The ability to alter one's identity as one wishes ispowerful, after all, it is the stuff that makes up many superhero narratives. Iwonder, however, when we will begin to see this potentially subversivepossibility as less a hindrance and more of an ability.

***

JavonJohnson is currently the Visions & Voices Provost's Postdoctoral Fellow atthe University of Southern California, where he teaches in the Department ofAmerican Studies & Ethnicity. He earned his Ph.D. in Performance Studies,with a cognate in African American Studies and a certificate in Gender Studies,from Northwestern University. He is a back-to-back national poetry slamchampion (2003 & 2004), has appeared on HBO's Def Poetry Jam,BET's Lyric Café, and co-wrote a documentary titled Crossover, whichaired on Showtime, in collaboration with the NBA and Nike. He has written forOur Weekly, Text & Performance Quarterly, and is currently working on hisbook, tentatively titled, Owning Blackness: Poetry Slams and the Making ofSpoken Word Communities.[image error]

Published on October 26, 2011 15:14

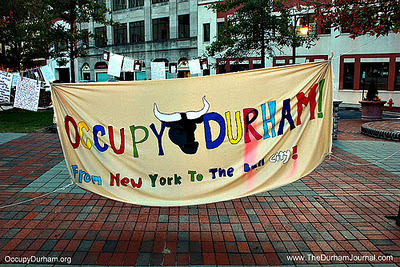

Belly of the Beast: From Durham to Wall Street

Bellyof the Beast: From Durham to Wall Street by Lamont Lilly | special to NewBlackMan

The scene was a perfect storm of organizedchaos. Here were the young andold, students & workers, immigrants and oppressed, all addressing thefailures of capitalism's current worldwide crisis, outlining the destructiveforces of global banking systems and highlighting the lack of communal valuesin a place that loves to cry patriotism. Right-winged conservative press wouldhave you to believe that the only "fanatics" there were Ivy League white collegekids—the privileged and idle-minded, or simply a cadre of recent graduates whohave yet to find jobs after completing Master's Degrees. But that wasn't trueat all. The idea of occupying WallStreet may have begun as a young white thing, but by the time we arrived on theevening of October 8th, there were participants of all nations, allraces and all ages—raising a range of pertinent issues.

There were Haitians from the Bronx who hadmarched the George Washington Bridge earlier that day in a show of solidarity.There were domestic and sanitation workers from Queens. There were the unionsand labor organizations from all over the country—Working Class adults whocurrently live the effects of capitalism from the front line, Blue-collarfolks whose wages have been decimated by the manipulation of global markets,international corporatism and "Third World" exploitation. For this one night, Iwas living what Democracy really looks like: the common masses united in a singlefront.

Creatively illustrated cardboard waseverywhere. Homemade signs and justice banners waited on deck for live action.While some were large and others were small, all were quite grand in stature,bearing sharp demands and philosophical ideals such as "Books not Bombs" and "Stopthe War on the Poor." It was atrue Who's Who of change slogans. There were also posters of Troy Davis and Mumia Abu-Jamal. However, nearly everyone possessed ananti-capitalist placard of some sort. The LGBT community was also infull-effect, but that was merely the surface.

There, within this tightly restrictedpark-ground was everything a revolutionary would need for a couple of months,that is, aside from a public restroom. There were mass water dispensers andcommunity chow lines, a first aid station equipped with medics, and an immenselibrary for learning and entertainment. There were sleeping bags, tents andthinly padded nap mats for rest and relaxation. There was art and music, loveand hope. There was one common cause and one loud voice: The People. No lobbyists or politicians wereallowed. No bureaucrats or corporate bourgeoisie were welcomed.

Sure, to some, it was a festival. Whilewalking around attempting to find a place to post my belongings, I ran across whatappeared to be an old makeshift reggae band—four middle-aged white men with goldenlocked hair and long beards, sitting on the ground with their guitars, fumblingthrough Bob Marley's, "Redemption Song." I jumped in, considering they onlyknew half the words to one of my personal favorites. There I was, howling to the top of my lungs with fourstrangers. We were 30 yards from the Occupy Wall Street drummers.

However, on the North End there were seriouspolitics being discussed. I wascompletely awed by their covert development of order and social structure. Formally entitled, The GeneralAssembly, there were 500 or so people tightly interwoven in a scattered circle,Indian style.

There were no microphones. Yet, all could beheard via the systematic rippling effect where each phrase was repeated backwards,twice. There was no President or Speaker of the House to go through in order tobe heard—no political red tape to be understood. Here, any man, woman or child who wanted to address themasses was permitted to do so by simply waiting behind "the podium," (a smallgroup of steep opal-shaped steps perpendicular from the street).

During the Assembly, it was clear that a widearray of interests were there in attendance. However, I don't recall one timethere being any certain individual or targeted companies mentioned. It wasn'tabout hate or animosity, at least not that particular night. It encompassedmore of a rallying of sociopolitical thought, a brewing of further direction—agalvanization based on commonality and mutual strands of oppression. Spiritswere high and emotions were free. For those who've grown up in the BlackChurch, it was the embodiment of a Pentecostal Worship Service, a Holy Ghosthour, primarily reserved for Human Rights activists, anti-capitalists andconcerned citizens at-large. Of course Dr. King would have supported the OccupyMovement. These were some of thesame issues MLK advocated for through his, Poor People's Campaign in the springof 1968—through his efforts with the Sanitation workers in Memphis, TN.

Purpose and the Point

What the general public or your casual Fox Newsconsumer has failed to understand, is the power of struggle and its catalyticability to unite the oppressed and disenfranchised. These whirlwinds of local protests sprouting across the countryaren't simply about disproportionate tax benefits, financial inequality andcorporate greed. It's far bigger than just the "rich and poor." Thecomplexities of the issues are much more intertwined than that. This is aboutthe mismanagement of Human Capital—the manipulation of the common massesworldwide. This is about the audacity of the "haves" who obviously don't give adamn, who could care less whether your home was foreclosed last year or not, orwhether your daughter had a decent meal at her public school today. The 1% aren'tconcerned with Racism, Sexism and Homophobia. Worker's Rights doesn't affect them. Social class is nonexistent from the elite's perspective. Homelessveterans are "no such thing," while universal healthcare is considered a "wasteof money." But really, what else should we expect from a socioeconomic system thatbreeds such chiseled individualism? It's me, me, me, with an emphasis on "I."

However, there's something uniquely rugged aboutthis generation. We were the "Crack Babies," the children of Ronald Reagan. Growingup in the 80's, we witnessed first-hand how greed drives poverty, and in turn, howpoverty perpetuates crime. We understand fully that within our current socialfabric, someone's always going to lose. We ARE the Prison Industrial Complex! And we're the same ones who keep beingtold educational funds have run dry. Yet, we operate under the guise of agovernment that somehow finds scores of resources for military occupations.

This isn't about demands, folks. The OccupyPhenomenon is really about the People reclaiming our own destiny, producing ourown change from the ground-up. "Occupying" is about the connection of ALLoppressed people. Ultimately, what we desire is something better than theflesh-eating machine we've been feeding since Reaganomics. It's been eating us from the inside outfor three decades now, patiently preying upon the same Proletariat and Underclassthat helped to build and stabilize it.

Some have deemed the Occupy Movement, a leaderlessstruggle, but that's the whole point. We're all leaders and should be respected as such—not lied to, cheatedon and outright deceived by state-sponsored pimps swindling billions from the fewcrumbs we do have. Well, "We the People," have decided it's time torepresent ourselves, whether it's Raleigh or Wall Street. We're tired of beingWage Slaves. We're tired of ourjobs skipping town for open borders and vast NAFTA experiments. We're also tiredof a justice system that bears no resemblance of justice, at least not from OscarGrant's perspective. Yet, Republicans and Democrats alike wonder why the Peopleare taking to the street. Probably because that's the one place they nevercome. Power to the People! Powerto the Street!

***

Lamont Lilly is a contributing editor with theTriangle Free Press who recently served as an organizer with Cynthia McKinney's2011, "Report from Libya Tour."

Published on October 26, 2011 15:04

October 25, 2011

Coming Home: On Returning to A Parent's Final Place of Rest

[image error]

Coming Home: On Returning to A Parent'sFinal Place of RestbyMark Anthony Neal | NewBlackMan

Inmy mind home had always been that place where my parents resided. This is not to say that I don't have ahome that I share with a wife and two daughters, but that the very idea ofgoing home—to some mythical, long past moment—was always concretely related tothe place where my parents resided. I can't say that my home as a child was particularly warm; morefunctional than anything, and that is not to say that I didn't know that I wasloved, since I was indeed Arthur and Elsie's baby-boy and only child. My father's matter-of-fact way of going to work, six days a week, without comment or complaint (and in the shadow of mymother's out-sized personality) continues to color my workman-like approach toeverything from writing, to cooking Sunday morning breakfast (as he did),parenting and marriage.

Thesensibility that my father bequeathed to me, his son, may have been hisgreatest gift in the months immediately after his death. He died in his sleep one Februarynight, with his 73rd birthday a few months on the horizon, asmatter-of-factly as he lived, with little fuss. In the spirit of my mother and father's ying and yang, meantthat I was left with ying, unhinged by the death of her mother and husband amonth apart that winter. Andunhinged is how I might have described my own state in those months followingmy father's death, my untreated hypertension out-of-control, closing out whathad been nearly three-years of sleeplessness, in which I slept no more thanfour hours of sleep a night.

Thecloseted demons in my head that I kept at bay, by staying awake as often asphysically possible—and by always punching the keys—were loosed sometime in thespring after my father's death, when the reality hit, that my mother could nottake care of herself anymore; the demons have not returned to their closets.Even when I slept, I cried, lamenting my inability to care for my own mother,putting her in a nursing home, with the faint voices of elders suggesting thatBlack folk don't do that. It wasall that I could do to keep my sanity.

Mypenance would be having to destroy my home—the Bronx apartment that my parentsshared for the final thirty-two years of their marriage and that my motherbarely survived five months in without her husband. That home had become the site of a few bad memories,baby-boy spreading his wings in a career and life, that nobody in that littleproject apartment could have imagined when the three of us moved there in thespring of 1976, from our tenement building in the South Bronx that happened toalso house a yet unknown Hip-Hop feminist. I suspect that my mother expected that I would alwayshave a presence in that apartment, she wanted to keep me as close to her, withthe same force, that she fled her own mother's home, at age sixteen, leavingBaltimore and settling in New York City, returning occasionally for shortfamily trips, almost always without my father who was, of course, working.

WhenI chose to fly or flee, my mother laid the blame initially at the feet of thewoman who would marry her son and finally at the feet of that son and hisambition, an ambition that she indeed cultivated, not quite knowing it wouldreproduce in me (and later her grand-daughters) the very independence that kepther and her own mother at arms length until that last phone-call, literally onthe eve of my grand-mother's passing. I have also come to understand that the dementia that would ravage mymother's mind like wildfires in August, might have already been at play; I wastoo ambitious to notice.

Andso in the spring of 2009, thirty-three years after I first walked into thatBronx apartment, it became my punishment to throw away the life that my parentshad built for a son (and perhaps his family), who had little interest in cominghome. It was a sad joke to hearthe unknowing and the never knowing, ask if I was gonna hold an estate sale,not quite understanding that my parents stuff—piles and piles of shitreally—were the kinds things thatno one wanted, even their son. Even the stacks of vinyl records that were once the greatest bondbetween a father and a son, had given way to new technologies. My father wasnever gonna listen to those Mighty Clouds of Joy albums that I had digitizedtwo years earlier. Piece by piece,over several months, and with a little help from my wife and a best-friend,whose friendship was even older than the time my parents spent in thatapartment, I gutted that apartment; gutted my home.

Iperiodically dream that I am back in that apartment, aged 16, my wings about totake flight, windows wide open and both my parents are there with me, and IsaacHayes's Black Moses in playing in thebackground. There are also dreamsof some breezy future that will never happen, where we are all wearing white,their grand-daughters bringing them scones and real cream for their coffee,sitting in a house that looks quite like the one I live in now.

Truthis, when my mother finally went home in the summer of 2009, I matter-of-factlymarked the occasion, as my father might have, had he been as ambitious as me. My blood pressure dropped twenty pointsthe day after. I had been mourning the woman that had been my mother since myfather's death; the last time she remotely resembled that woman. Fittingly, my mother died and wasburied in Baltimore, the very place she fled from as a teen-ager exactly fifty-years earlier, only to be buriednext to the woman she had fled from in the first place, along with my father'sremains. I had stopped calling NewYork—The Bronx—my home, I had no home, and no parents to return to, somethingthe younger, more ambitious version of myself could have never fathomed.

Ona recent October morning, I returned to that cemetery for the first time sincemy mother was lowered into the earth. Though my trip to Baltimore had been planned months inadvance and I had already made arrangements to spend some time with one of myaunts, the thought of visiting my parents' gravesite never once crossed my mind. Yet as I drove into the cityfrom the airport, I could hear my parents calling to me; they wanted me tovisit. As if choreographed inadvance, I spent several minutes trudging in the wet grass, searching for theirstone markers. It was only as Icomplained out-loud that it was typical of them to put me through suchchanges—I was checking my watch for a presentation that I would never make—thatI stumbled over their marker.

Itwas a matter-of-fact reunion—reinforced by the auntie, who later in the carasked me more than a few times if I was okay—as I told them how proud theywould be of their grand-daughters, both of whom possess their grandmother'sspirit, to my daily dismay. Ithanked them, for imagining a future for their baby-boy, that none of us couldhave ever expected, but that they had indeed planned for, not with money, butrather matter-of-factly. I clearedtheir stones of cut grass and that of my grandmother, and was back in the carminutes later; back to myambition.

Coming Home: On Returning to A Parent'sFinal Place of RestbyMark Anthony Neal | NewBlackMan

Inmy mind home had always been that place where my parents resided. This is not to say that I don't have ahome that I share with a wife and two daughters, but that the very idea ofgoing home—to some mythical, long past moment—was always concretely related tothe place where my parents resided. I can't say that my home as a child was particularly warm; morefunctional than anything, and that is not to say that I didn't know that I wasloved, since I was indeed Arthur and Elsie's baby-boy and only child. My father's matter-of-fact way of going to work, six days a week, without comment or complaint (and in the shadow of mymother's out-sized personality) continues to color my workman-like approach toeverything from writing, to cooking Sunday morning breakfast (as he did),parenting and marriage.

Thesensibility that my father bequeathed to me, his son, may have been hisgreatest gift in the months immediately after his death. He died in his sleep one Februarynight, with his 73rd birthday a few months on the horizon, asmatter-of-factly as he lived, with little fuss. In the spirit of my mother and father's ying and yang, meantthat I was left with ying, unhinged by the death of her mother and husband amonth apart that winter. Andunhinged is how I might have described my own state in those months followingmy father's death, my untreated hypertension out-of-control, closing out whathad been nearly three-years of sleeplessness, in which I slept no more thanfour hours of sleep a night.

Thecloseted demons in my head that I kept at bay, by staying awake as often asphysically possible—and by always punching the keys—were loosed sometime in thespring after my father's death, when the reality hit, that my mother could nottake care of herself anymore; the demons have not returned to their closets.Even when I slept, I cried, lamenting my inability to care for my own mother,putting her in a nursing home, with the faint voices of elders suggesting thatBlack folk don't do that. It wasall that I could do to keep my sanity.

Mypenance would be having to destroy my home—the Bronx apartment that my parentsshared for the final thirty-two years of their marriage and that my motherbarely survived five months in without her husband. That home had become the site of a few bad memories,baby-boy spreading his wings in a career and life, that nobody in that littleproject apartment could have imagined when the three of us moved there in thespring of 1976, from our tenement building in the South Bronx that happened toalso house a yet unknown Hip-Hop feminist. I suspect that my mother expected that I would alwayshave a presence in that apartment, she wanted to keep me as close to her, withthe same force, that she fled her own mother's home, at age sixteen, leavingBaltimore and settling in New York City, returning occasionally for shortfamily trips, almost always without my father who was, of course, working.

WhenI chose to fly or flee, my mother laid the blame initially at the feet of thewoman who would marry her son and finally at the feet of that son and hisambition, an ambition that she indeed cultivated, not quite knowing it wouldreproduce in me (and later her grand-daughters) the very independence that kepther and her own mother at arms length until that last phone-call, literally onthe eve of my grand-mother's passing. I have also come to understand that the dementia that would ravage mymother's mind like wildfires in August, might have already been at play; I wastoo ambitious to notice.

Andso in the spring of 2009, thirty-three years after I first walked into thatBronx apartment, it became my punishment to throw away the life that my parentshad built for a son (and perhaps his family), who had little interest in cominghome. It was a sad joke to hearthe unknowing and the never knowing, ask if I was gonna hold an estate sale,not quite understanding that my parents stuff—piles and piles of shitreally—were the kinds things thatno one wanted, even their son. Even the stacks of vinyl records that were once the greatest bondbetween a father and a son, had given way to new technologies. My father wasnever gonna listen to those Mighty Clouds of Joy albums that I had digitizedtwo years earlier. Piece by piece,over several months, and with a little help from my wife and a best-friend,whose friendship was even older than the time my parents spent in thatapartment, I gutted that apartment; gutted my home.

Iperiodically dream that I am back in that apartment, aged 16, my wings about totake flight, windows wide open and both my parents are there with me, and IsaacHayes's Black Moses in playing in thebackground. There are also dreamsof some breezy future that will never happen, where we are all wearing white,their grand-daughters bringing them scones and real cream for their coffee,sitting in a house that looks quite like the one I live in now.

Truthis, when my mother finally went home in the summer of 2009, I matter-of-factlymarked the occasion, as my father might have, had he been as ambitious as me. My blood pressure dropped twenty pointsthe day after. I had been mourning the woman that had been my mother since myfather's death; the last time she remotely resembled that woman. Fittingly, my mother died and wasburied in Baltimore, the very place she fled from as a teen-ager exactly fifty-years earlier, only to be buriednext to the woman she had fled from in the first place, along with my father'sremains. I had stopped calling NewYork—The Bronx—my home, I had no home, and no parents to return to, somethingthe younger, more ambitious version of myself could have never fathomed.

Ona recent October morning, I returned to that cemetery for the first time sincemy mother was lowered into the earth. Though my trip to Baltimore had been planned months inadvance and I had already made arrangements to spend some time with one of myaunts, the thought of visiting my parents' gravesite never once crossed my mind. Yet as I drove into the cityfrom the airport, I could hear my parents calling to me; they wanted me tovisit. As if choreographed inadvance, I spent several minutes trudging in the wet grass, searching for theirstone markers. It was only as Icomplained out-loud that it was typical of them to put me through suchchanges—I was checking my watch for a presentation that I would never make—thatI stumbled over their marker.

Itwas a matter-of-fact reunion—reinforced by the auntie, who later in the carasked me more than a few times if I was okay—as I told them how proud theywould be of their grand-daughters, both of whom possess their grandmother'sspirit, to my daily dismay. Ithanked them, for imagining a future for their baby-boy, that none of us couldhave ever expected, but that they had indeed planned for, not with money, butrather matter-of-factly. I clearedtheir stones of cut grass and that of my grandmother, and was back in the carminutes later; back to myambition.

Published on October 25, 2011 13:52

Left of Black Discusses Arab Spring and Hip-Hop Activism with Syrian American Artist Omar Offendum

Left of Black Discusses Arab Spring andHip-Hop Activism with Syrian American Artist Omar Offendum

OnWednesday October 26, 2011, Left of Black will feature SyrianAmerican Hip-Hop artist Omar Offendumand artist and educator Pierce Freelonof The Beast on a special live audiencetaping of the show, as part of the Wednesday at the Center programming at theJohn Hope Franklin Center for Interdisciplinary and International Studies atDuke University (Room 240).

Theconversation will also be streamed live on Duke University's Ustream channel. Viewers are invited to alsofollow the discussion via Twitter using the hashtags #LeftofBlack or #dukelive.

OmarOffendum is a Los Angeles-basedSyrian-American hip-hop artist. He began his musical career as member of theArabic-American Hip-Hop group N.O.M.A.D.S. Omar is committed to supportinghumanitarian aid for Palestine. His street performance and poetry projects havebeen reviewed among others by the BBC, ABC News and Al Jazeera. A bilingualartist, Omar performs in both Arabic and English, often bridging betweenAmerican and Middle Eastern cultures by translating and performingEnglish-language poetry in Arabic for Arabic audiences and Arabic songs forAmerican audiences.

Pierce Freelon is an emcee, professor, activist and the founder of Blackademcis.org .He earned his bachelors degree in African and African American Studies from theUniversity of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with highest honors and his mastersdegree in Pan-African Studies from Syracuse University. At UNC, Freelondeveloped a Hip-Hop curriculum, which he has taken into high schools anduniversities from South Central to Atlanta and from southeast Asia to WestAfrica. He is currently an adjunct professor at North Carolina CentralUniversity and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where heteaches Music and Political Movements and Blacks and Popular Culture.

Left of Black is hosted by DukeUniversity Professor Mark AnthonyNeal and recorded and produced at the JohnHope Franklin Center of International and Interdisciplinary Studies at DukeUniversity.###

Published on October 25, 2011 12:46

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.