Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1051

October 19, 2011

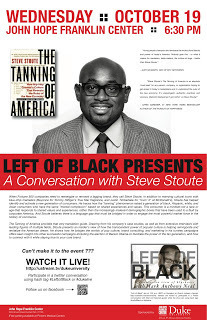

The Vision of Steve Stoute: My Passport Says Shawn

Left of Black Presents: A Conversation with Steve Stoute

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 19, 6:30 PM JOHN HOPE FRANKLIN CENTER FOR INTERDISCIPLINARY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES

Please join us on the set of Left of Black in room 240 of the John Hope Franklin Center for a live, streamed (http://www.ustream.tv/dukeuniversity), conversation with Steve Stoute, author of the newly The Tanning of America - How Hip-Hop Created a Culture That Rewrote the Rules of the New Economy and founder and chief creative officer of Translation Consultation + Brand Imaging .

Published on October 19, 2011 05:24

October 18, 2011

A King for Our Times

A King forOur Timesby Davarian Baldwin | special to NewBlackMan

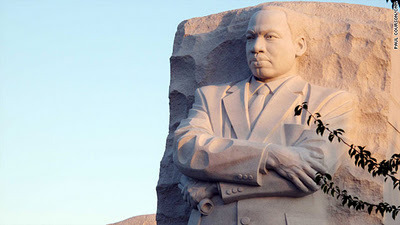

On Sunday, October 17, 2011, Dr. Martin Luther KingJr. stood, arms crossed, gazing out over the Tidal Basin on the National Mall.Once again he was surrounded by tens of thousands of people. Only this time, hewas 30 feet tall, ensconced in granite, and etched with quotes from hishistoric speeches. All had gathered for thededication of the long awaited monument for civil rights icon Martin LutherKing. Yet it's important to note that likeSisyphus pushing that boulder up a hill only to watch it roll back down, King'smonument dedication seemed destined to never happen. For decades the memorialfaced struggles with funding. Once plans moved forward many then grumbled aboutthe "political correctness" of placing a civilian, a common man, "who happenedto be African American," next to presidents. Finally, once the date had beenset, the monument dedication had to be rescheduled because of the howling windsof Hurricane Irene. So in a way that best commemorated the legacy of King, hismemorial faced a range of struggles and still…overcame.

Under clear blue skies it was apparent King had onceagain drawn a cross section of Americana to the seat of national governance. Inattendance were Civil Rights stalwarts who had walked next to King, some nowmoving much more slowly and aided by wheelchairs or walkers. The sun-kissedcrowd was a mix of young, old, some in strollers, some having no idea who Kingwas, staring behind searching eyes only knowing that they were told they wereattending an historic event. And to be sure, it was an historic event…for anumber of reasons. Notably, an African American president presided over theproceedings from the podium while the distinguished Princeton Universityprofessor and public intellectual, Cornel West looked on from the audience. Ina way, King had put a momentary hiatus on what had been months of politicaldisagreements (some say more ego-driven than ideological) between these twoprominent African American men, both inheritors of King's dream. But more importantthan who they were, it is equally telling to track where these two men were"coming from" on that clear and sunny day.

Obama had just come from a "beatdown" by Republicanrepresentatives over the defeat of his long-term health care insurance plan. Heeven not-so-subtly referenced the "Occupy" events taking the nation by storm:"I believe he [King] would remind us that the unemployed worker can rightlychallenge the excesses of Wall Street without demonizing all who work there."While West left the dedication and headed straight away to an Occupy D.C. eventwhere an estimated 250 people set up camp on the steps of the Supreme Courtbuilding. He was summarily arrested for occupying public space to reportedlydenounce the court decisions that have opened the door to greater corporateinfluence on governmental decisions. Many scoffed at the very audacity of Westor anyone, but especially Obama, "highjacking" the memorial dedication andmentioning in the same breath King and the more than 200 Occupy protest eventsthat spread from Tuscaloosa, Alabama to the Saskatchewan province in Canada.These caretakers of "The Dream" emphasize the "King qualities" of silentsuffering in the face of violent attacks, attempts to connect with a largermoral conscience, and a "rights-based" appeal through official politicalchannels. Therefore, mention of King in the same discussion of the Occupyevents is dismissed as sacrilegious.

In a sense, once the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and theVoting Rights Act of 1965 were passed, King's relevance seemed to also pass.Therefore, the current struggles over health care, unemployment, the corporatecontrol of government, the protests of various interest groups work againstKing's grander appeals to an American "we." But then those of us with anyhistorical memory or those invested in social justice, scratch our heads andwonder precisely who is this King that has been memorialized in granite and ina sense frozen in time; caricatured at the "I Have a Dream" moment of his life andconfined to the "content of our character" phrase for at least the last thirtyyears. What do we lose in the struggle to make the American public feel that a Kingmemorial dedication stands in opposition to our current economic climate? We losea King for our times.

We lose the 1967 King, who at Riverside Church in NewYork City defied the Civil Rights establishment to make links between what hesaw as a colonial war in Vietnam with a failure to achieve racial equality andsocio-economic justice at home. We lose the King who was assassinated inMemphis, Tennessee organizing primarily Black garbage workers fighting forbetter wages and racial dignity as part of his larger Poor People's campaign.We lose the King who said Progress is meaningless when the economy expands andstock values rise but millions of people remain unemployed or underpaid,without health care, a pension or economic security. We lose a King whodescribed American capitalism as "socialism for the rich and free markets forthe poor;" who linked urban poverty with suburban plenty. We lose a King thatwould comfort and rest beside those occupy protestors, as they sleep under thestars in open air encampments. We lose a King for our times.

Now I am not one who peddles in useless speculationsabout how King would vote or which political position sitsthatone day all of God's children will have food and clothing and materialwell-being for their bodies, culture and education for their minds and freedomfor their spirits.

In my mind, this is the King for our times. This isKing the Christian preacher and the world citizen. This is the King who openlyadmired American presidents and Trinidadian Marxist C.L.R. James. This is theKing who made appeals to Civil Rights but when faced with urban northernpoverty strangling black communities that had rights, he expanded his politicalvision to something greater. This is a King who saw the redistribution of statepower and economic wealth as part of the American Creed. This is the King whounderstood social justice as an act of love and not mere sentiment. Perhaps ifcitizens had listened to all King had to say we wouldn't be faced with such adaunting task ahead. And therefore as we dedicate a memorial to Dr. MartinLuther King Jr. let nobody turn us around, let no one tell us who he is. Kinglives in our current struggles and remains a drum major for justiceunfulfilled. We need his full legacy now, more than ever before.

***

Davarian L. Baldwin the Paul E. Raether Distinguished Professor of American Studiesat Trinity College. Baldwin is the author of Chicago's New Negroes: Modernity, the Great Migration, and Black UrbanLife (UNC, 2007). He is also co-editor, with Minkah Makalani, of the essaycollection Escape From New York! The'Harlem Renaissance' Reconsidered (forthcoming from the University ofMinnesota Press). Baldwin is currently at work on two new projects, Land of Darkness: Chicago and the Making ofRace in Modern America (Oxford University Press) and UniverCities: How Higher Education isTransforming the Urban Landscape.

Published on October 18, 2011 19:45

The Vision of Steve Stoute: Gwen Stefani and HP

Left of Black Presents: A Conversation with Steve Stoute

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 19, 6:30 PM JOHN HOPE FRANKLIN CENTER FOR INTERDISCIPLINARY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES

Please join us on the set of Left of Black in room 240 of the John Hope Franklin Center for a live, streamed, conversation with Steve Stoute, author of the newly The Tanning of America - How Hip-Hop Created a Culture That Rewrote the Rules of the New Economy and founder and chief creative officer of Translation Consultation + Brand Imaging .

Published on October 18, 2011 19:17

The Vision of Steve Stoute: The S. Carter Collection

Left of Black Presents: A Conversation with Steve Stoute

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 19, 6:30 PM JOHN HOPE FRANKLIN CENTER FOR INTERDISCIPLINARY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES

Please join us on the set of Left of Black in room 240 of the John Hope Franklin Center for a live, streamed, conversation with Steve Stoute, author of the newly The Tanning of America - How Hip-Hop Created a Culture That Rewrote the Rules of the New Economy and founder and chief creative officer of Translation Consultation + Brand Imaging .

Published on October 18, 2011 13:10

The Vision Of Steve Stoute: Reebok, Allen Iverson & Jadakiss

Left of Black Presents: A Conversation with Steve Stoute

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 19, 6:30 PM JOHN HOPE FRANKLIN CENTER FOR INTERDISCIPLINARY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES

Please join us on the set of Left of Black in room 240 of the John Hope Franklin Center for a live, streamed, conversation with Steve Stoute, author of the newly The Tanning of America - How Hip-Hop Created a Culture That Rewrote the Rules of the New Economy and founder and chief creative officer of Translation Consultation + Brand Imaging .

Published on October 18, 2011 05:53

October 17, 2011

Left of Black S2:E6 w/ Dr. Kenneth Montague and Kellie Jones

Left of Black S2:E6w/ Dr. Kenneth Montague and Kellie JonesOctober 17, 2011

Dr. Kenneth Montague, a Toronto-based dentist and the curator of Becoming: Photographs from the Wedge Collection , joins Left of Black host Mark Anthony Neal at the Nasher Museum in Durham, Carolina. The Windsor, Ontario born Montague has collected contemporary art since the 1990s, and was influenced by African American culture from across the Detroit River. Neal and Montague discuss some of the featured artists in the collection including Jamel Shabazz, Carrie Mae Weems, Malick Sidibé, and James VanDerZee, and the importance of collecting Black Art.

Later in the episode, Neal is joined via Skype© by Columbia University Art Historian Kellie Jones, author of the new book Eyeminded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art. Neal and Jones discuss her famous parents, Hettie Jones and Amiri Baraka, and her work as curator of the new exhibit, Now Dig this! Art and Black Los Angeles, 1960-1980 at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles.

***

Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University.

***

Episodes of Left of Black are also available for download @ iTunes U

Published on October 17, 2011 19:19

Not About a Salary, but a Racial Reality: The NBA Lockout in Technicolor

Not About a Salary, but a RacialReality: The NBA Lockout in TechnicolorbyDavid J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

Withthe NBA lockout reaching a new low (or a return low) with David Stern'sannouncement of the cancellation of the first two weeks, the class of punditshave taken to the airwaves to lament the developments, to asses blame, andoffer suggestions of where to go from here. Not surprisingly, much of the commentaries have blamedplayers for poor tactical decisions, for wasting any potential they may havehad over the summer, and for otherwise being too passive. Take HarveyAraton, from The New York Times,who while arguing that the players will need to take risks in order to secureleverage, speculates about a potential missed opportunity:

If it sounds unrealistic tosuggest that the modern player might have considered striking first — or atleast threatening one before last spring's playoffs — that is only because thetactic has become virtually anathema, which is a mighty curious weapon for aunion to concede.

While on the phone, Fleisherlooked up the language in the expired collective bargaining agreement on Pages264-265 that prohibited players from impeding N.B.A. operations. But supposingthe players had gone ahead and walked out on the eve of the playoffs afterthey'd all been paid their regular-season hauls?

Fleisher guessed they wouldhave opened themselves and their individual contracts up to a court action. Ormaybe the owners — petrified at the thought of their profit season beingflushed — might have agreed to a no-lockout pledge for the start of thisseason. Who knows? But sometimes risk begets reward.

Whileabstract at a certain level, the argument makes sense. Had the players been more aggressive,had they taken steps earlier, had they capitalized on past leverage, thesituation might be different. Yet,we don't live in an abstract world. The realities on the ground precluded such steps (seehere for my past discussion). If the efforts to blame players, to demonize them as greedy,selfish, and out-of-touch during a LOCKOUT is any indication how the publicmight have reacted to a player strike, especially one starting at the playoffs,the strategy suggested here is pure silliness.

Moreover,it fails to understand the ways in which race operates in the context of sportsand within broader society. Thepublic outcry against LeBron James for exercising his rights of free agency,the condemnation of Deron Williams or Carmelo Anthony for deciding that theywanted to play elsewhere, and the overall vitriol directed at playersillustrates both the impossibility of any player leverage and the ways in whichrace undermines any structural power the players may enjoy. The owners possess the power of theracial narrative that both guides public opinion and fan reaction.

Wecan make similar links to the larger history of African American laborstruggles, where black workers have struggled to secure support from the publicat large because of longstanding ideas of the lack of fitness/desirability ofAfrican Americans in the labor force. In other words, fans, just as the public in past labor struggles, seethe black body as inherently undeserving and thus any demands for fairness, equality,and justice are seen as lacking merit. On all counts, the commentaries fail to see the ways andwhich blackness and anti-black racism constraints the tools available to theplayers.

Eventhose commentaries that ostensibly exonerate the players in highlighting DavidStern's strategy of throwing the players under the proverbial racial bus (hisrace card) with the hopes that the public will ultimately turn against theplayers (mostly there already) erases race from the discussion. For example, in "Stern ducks, lets NBA players take hit," AdrianWojnarowski highlights the difficulty facing NBA players and how that realityguides the intransigent position from the firm of Stern and owners. "So, there was the biggest star in thesport waddling onto the sidewalk on 63rd Street in Manhattan on Monday nightwithout the kind of big-stage, big-event scene that the commissioner alwaysloves for himself in the good times," he writes. "He knows the drill now: Stepout of the way, and let the angry mobs run past him and the owners. Let themchase his players down the street, around the corner and all the way to thelockout's end and beyond." Similarly, BudShaw penned the following:

Blaminglocked-out players in a work stoppage? Sounds like a plan, just one that defieslogic.

A playerstrike didn't cause a partial cancellation of the schedule. Commissioner Bully madethe call, doing the bidding of an ownership whose strategy is to watch playerssquirm when they start missing checks and wait for the inevitable wave ofpublic resentment to crash down on their heads.

After DavidStern's announcement, LeBron James tweeted an apology to fans for the lost games.Steve Nash aimed his regrets at those hurt most by the cancellation, saying"sorry to all the employees in and around NBA arenas losing work."The owners are betting you'll read over that and do what fans always do inthese situations. Scoff and say, "Sorry? Sure they are. I'd play for aquarter of what those guys make

Thereason Stern can step aside and "let them chase his players down the street"(he certainly uses language to convey a lynch mob mentality) are grounded inanti-black racism.

Classmatters and surely the current economic crisis matters, but when the strategyof ownership is to lock their workers out and when those workers offer a concessionof at least 160 million (reduction of player's take of the BRI from 57% to53%), it is hard to argue that class disintentification drives fans and thepublic at large from players to owners. Race and the power of a white racial frame that imprisons black malebodies to a narrative of criminality, danger, pathology and greed, thatconstructs blackness as undeserving, unintelligent, unprofessional, and notpart of the mainstream, highlights the basis of this strategy.

Thelockout isn't simply about increased profits and changing the structure of theNBA so that the Cavs, Kings, and Bobcats have as much of a chance of winning anNBA championship as the Heat and the Lakers (this portion of the argumentremains suspect to me since clearly a NBA finals between the Bobcats-Kingsfinals does little to improve revenues). It as much about breaking the union, disciplining and managing theleague's black bodies in an effort to secure victory in the NBA's assault onblackness. It is both an effort tocapitalize on anti-black racism through playing on fan/media contempt all whileenhancing their profit margins (constrained by anti-black racism) and power totransform the criminalized black body into a more profitable entity.

In 2006, Kobe Bryant had not yet returned to his prominence within theNBA. In wake of accusations ofsexual violence and his often-publicized feud with Shaquille O'Neal, Koberemained a suspect superstar incapable of converting talents to profits for theleague and its corporate sponsors. That year, he did secure his place inhistory when he scored 81 points in a January game. Notwithstanding the historic nature of this performance, hisdropping 81 on the Raptors led numerous commentators to question Kobe'scommitment to his team/the game, using the moment to lament his inability tobecome the next MJ. On the web, innewspapers, on sports talk radio, and on the various television sports debateshows, fans and sport commentators debated whether scoring 81 points was indeeda great accomplishment or a sign of a character flaw in Bryant, and thus a signof the precarious future for the NBA.

Interestingly,similar conversations took place earlier in the season, when Bryant dropped 61on the Dallas Mavericks in three quarters. With his team up by 40, Bryant did not play the fourthquarter, prompting fans and sports reporters to deem Bryant as selfish for hedid not return to the game in search of Wilt Chamberlin's 100 points in a gamerecord. Greatness on the court wasone thing, but his purported selfishness, his me-first attitude, and overalldisrespect for his teammates, opponents, the fans, and the game itself,embodied the problems facing the NBA.

Scoring 81 pointsserved as a signifier for his place as both a dollar sign and a thug within thedominant white imagination; he was marketable, yet limited as a commoditybecause he was unable to transcend the meaning of blackness. In this instance, he, like so many NBAballers, functioned as the ultimate marker of the decay facing the NBA,functioning as both a source of celebration and a spectacle where thediscursive logic and ideological rhetoric played out on, through and within hisbody. In other words, Bryant'sgreatness did not propel the league forward because his greatness fedanti-black stereotypes and narratives.

The NBA'sstrategy of marketing players over teams, of commodifying stars over rivalries provedineffective because of the wider meaning conveyed by blackness within the whiteimagination. The lockoutrepresents a reversal of this strategy by both undermining the star power ofthe NBA's elite players all while trying to create team parity. Since the next Michael Jordan, asa post-racial fiction, appears no where in the NBA's future, the league is seton restructuring itself to further conceal its blackness even while it playsupon anti-black sentiments to cultivate support for ITS cancellation ofgames. It ain't about their salary,it's about the race of the NBA reality that guides the NBA lockout and itsreception.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of CriticalCulture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He isthe author of Screens Fade to Black:Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop(SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan and blogs @ No Tsuris.

Published on October 17, 2011 19:06

#OccupyWallStreet Brings Back a Great New York Tradition of Street Speaking and Open Air Debate

Parliament ofthe People: #OccupyWallStreetBrings Back a Great New York Tradition of Street Speaking and Open Air Debate byMark Naison | special to NewBlackMan

Oneof the most remarkable features of Occupy Wall Street is the number of teachins, discussions and debates that take place at Zucotti Park during daylight hours. Discussion and debate is continuous, some of it one on one, someof it in small groups, some taking the form of large assemblies .And the rangeof topics is broad, ranging from education policy, to problems in the middleeast, to the sources of the current economic crisis, to problems of racism andanti-semitism, to how to diversify the Occupation. I have not, since thedays I was an undergraduate at Columbia in the mid 60's and participated indebates and rallies at the Sundial in the middle of campus experienced this much intellectual vitality in an outdoor setting. And it was something I had never seen first hand in a New York neighborhood.

Butas a historian of social movements, who had once written a book about Harlem inthe 1920's, 1930's and 1940's this was all familiar to me. There was once atime in the history of New York City when Harlem, and to a lesser degree theLower East Side, Brownsville and the South Bronx were filled withspeakers on every corner explaining Socialism and Capitalism, promotingor attacking organized religion, extolling the value Zionism, BlackNationalism, or Irish Independence, and at times, giving impromptu courses onworld history.

Noplace was this tradition of street speaking more developed than inHarlem, the nation's largest and most diverse Black community during theyears in question, where one commentator referred to it as the "Parliament ofthe People." On any afternoon in 1919, you might find Marcus Garvey, APhillip Randolph, Richard Moore and Hubert Harrison on different streetcorners, each espousing their particular philosophies before large andenthusiastic crowds. During the 1930's, those same streets featureddebates between Communists and Garveyites, while leftists organizedcommunity members to put back the furniture back of evicted families,nationalists urged them join "Don't Buy Where You Can't Work"campaigns," and religious orators promised salvation in various forms. This tradition continued on into the 1950's and early 1960's where on a givenday, you could hear Malcolm X holding forth about the Nation of Islam, QueenMother Moore and Carlos Cooks talking about reparations, or Charles Kenyattaurging the community to "Buy Black."

Thisopen air forum created an atmosphere where working class people in Harlemand other New York neighborhoods, whether domestics, Pullman porter, cabdrivers, factory workers or teachers and nurses,, had an almost daily exposure topolitics, religion, history and current events right in their own neighborhood.It created a working class public that was alert, vigilant, andpolitically active and fought for its interests. It was no accident that in thepost war years, New York was a city which had free zoos and museums, greatafter school programs and sports and arts in its public schools, and freetuition at its City Universities, as well as a vibrant civil rightsmovement that fought discrimination in housing, education and employment.

Throughthe 1970's, 1980's and 1990's this tradition of street speaking and publicdebate gradually disappeared. The streets of working class neighborhoodsretained their vitality, but it came largely from street vendors and religiousspeakers rather than people promoting political activism or knowledge of worldhistory.

Nowhowever, at Zuccotti Park, the Parliament of the People seems to have returned.Debates, both organized and spontaneous, break out at all hours of the day (andfor all I know, the night!) and people are able to get many points of viewacross to eager listeners. All of a sudden, political discussion hasbecome cool again, but more importantly, people are beginning to feel theirviews matter because they haveseen, as the Occupation evolves, how ordinary people when joined together foraction can do things they previously thought were impossible.

Nowyou can say that Occupy Wall Street is an elitist movement and that thepolitical vitality in open space displayed there once spread to the workingclass communities where it is most needed. But there are signs that it isspreading to communities of color around New York.

OnSaturday, I was at an Occupy the Bronx event on Fordham road which began with aTeach in about green cooperatives and ended with a speak out on conditions inthe Bronx at which more than 15 people presented their views. There were75 to 100 people assembled, but passerby's often stopped to listen. WhenI got up to speak, it was an incredibly moving experience because I had notgiven a speech on Fordham road since the heyday of the anti-war movement in theearly 1970's. But the issues here were not ones that were goingaway-unemployment, the mal-distribution of wealth, poor health care , lack ofaffordable housing, police harassment of Black and Latino youth. If theOccupation Movement continues to grow, discussions like this may proliferate,bringing with it a renewed confidence, not only that ideas matter, but thatpeople can change their communities through collective action.

Spacematters. The ability of the Occupy Wall Street movement to hold Zuccotti Parkin the for more than five weeks in the face of first profound skepticism of themovement's staying power and more recently of efforts by authorities to evictit has turned that park into a center of grass roots democratic practice anddiscourse. But thought the occupation is new, the discourse is not!It is something we once had in many New York working class neighborhoods.

Solet us follow the example of the Occupation and transform streets like FordhamRoad, 125th Street, Jamaica Avenue and Fulton Street into "Parliaments of thePeople" where political discussion and debate and thrive and people can planthe next steps to revitalize neighborhoods without driving working class peopleout, and to use the wealth created in our city to advance the common goodrather than the interest of the 1 Percent.

***

Mark Naisonis a Professor of African-American Studies and History at Fordham Universityand Director of Fordham's Urban Studies Program. He is the author of two books,Communists in Harlem During theDepression and White Boy: A Memoir.Naison is also co-director of the Bronx African American History Project(BAAHP). Research from the BAAHP will be published in a forthcoming collectionof oral histories Before the Fires: AnOral History of African American Life From the 1930's to the 1960's.

Published on October 17, 2011 14:04

October 16, 2011

A Tale of Two Publics: Reflections on the Anita Hill-Clarence Thomas Hearings

Anita Hill Defense Team including Charles Ogletree, JanetNapolitano & Kimberle Crenshaw

ATale of Two Publics: Reflectionson the Anita Hill-Clarence Thomas Hearings byMark Anthony Neal | NewBlackMan

Twenty-yearsago when Professor Anita Hill testified in front of the Senate JudiciaryCommittee, investigating sexual harassment charges against Supreme Courtnominee Clarence Thomas, I was in my first semester in graduate school. Twenty-years later I recall thosehearings as a foundational moment in my development as feminist. As is so oftenthe case with Blackness, the hearings resonated in contemporary Americanculture for years to come—largely as spectacle—continuing to frame many of ourconversations about sexual harassment in the work place. Few in mainstreamAmerican culture seemed inclined believe Professor Hill's claim that she washarassed; Justice Thomas was confirmed in the closet vote in the history ofSupreme Court confirmations. Yet such sentiment seemed even more palpablewithin Black publics, or what political scientist Lester Spence, Jr. calls the BlackParallel Public.

Inher book Codes of Conduct: Race, Ethics,and the Color of Our Character, literary and legal scholar Karla FCHolloway, notes that Professor Hill's testimony "captures the visual and spokendimension of a testimony of exile…the inquisition of her body and theinterrogation of her words demonstrated the displaced subjectivity of analtered state of black identity." Considered another way, Holloway's comments capture the distinctlydifferent ways that the Hill-Thomas hearings were consumed along racial,gendered and class lines. Most inWhite America were not privy to the rich and raucous debates over gender thatraged in Black publics; that the Hill-Thomas hearings raised the ante in theform of public spectacle only highlights that for Black America, it was neversimply about Justice Thomas replacing retired Justice Thurgood Marshall as thehigh court's "Black" justice.

TheHill-Thomas hearings came on the heels of several high profile controversiesregarding black female and male relations. Debates about Black gender politicsbecame particularly virulent after the publication and subsequent filmadaptation of Alice Walker's novel TheColor Purple. When the film premieredin December of 1985, journalist and talk-show host Tony Brown—who hadn't readthe book or seen the film—famously decried, "I know that many of us who are male and black are toohealthy to pay to be abused by a white man's movie focusing on our failures,"helping to spearhead public protests at the film's screenings.

Afew years later, as heavyweight boxer Mike Tyson rose to the pinnacle of hissport, his marriage to actress Robin Givens established them as the first Blackcelebrity couple of the digital era—before Bobby and Whitney, Will and Jada,Beyonce and Shawn. Tyson andGivens' train-wreck of a relationship reached its most critical moment during aprime-time interview with Barbara Walters, where Givens admitted that Tyson physicallyabused her, while a contrite—and heavily medicated—Tyson simply nodded hishead. Black public opinion though, focused not on Tyson's abuse—leta man, be a man, right?—but rather on Givens and her mother Ruth Roper, whowere easily cast as duplicitous Black women aiming to undermine Tyson (and takehis money), and by extension, Black patriarchy. Givens and Roper's ultimate crime was the airing of Tyson'sdirty laundry, a charge that resonated powerfully with some Black publicsduring the Hill-Thomas hearings.

Finallythere was the case of Denise "Dee" Barnes, then host of the weekly music videoprogram, Pump It Up. Members of the group N.W.A., thenled by producer Dr. Dre (Andre Young) and the late Eazy-E (Eric Wright), tookoffense when they perceived Barnes as allowing former NWA member Ice Cube (O'SheaJackson) to sleight them during her interview with him. Rather than physically confront IceCube over his comments—they would famously exchange barbed lyrics instead—Dr.Dre confronted Barnes at an industry party and assaulted her, while hisbodyguards kept on-lookers away. Occurring ten months before the Hill-Thomas hearings, the incident is perhaps most notable forthe lack of response it generated, both within hip-hop circles and Blackcommunities at large. The silenceled feminist writer and critic Pearl Cleage to opine, "There had been no outcryfrom the black women writers (including me) who are old enough to be [Barnes']mother and who have participated in vocal and sustained defenses of sistersAlice Walker, Ntozake Shange and Gloria Naylor when they were attacked by blackmen for creating 'negative images.'"

Providinga finer perspective, Cleage further queries, "What if Amiri Baraka had takenphysical issue with Ntozake Shange's play ForColored Girls… and punched her out at a reading at Oxford Bookstore?"Unspoken, yet clearly heard in Cleage's observations is that fact that within apolitics of Black respectability, where airing dirty laundry is a capitaloffense, often deserving or social death, the silence associated with Barnes'assault, as well as the castigation of Walker, Givens and Roper, was a policingfunction, that would have ramifications as Professor Hill sat in judgment (asopposed to Thomas) in October of 1991. Cleage's own work was in response to thepopularity of Shaharazede Ali's self-published pamphlet, The Blackman's Guide to Understanding the Blackwomen, whichliterally advocated hitting black women in the mouth for daring to speak criticallyabout Black men. While WhiteAmerica was oblivious to Ali (though the publishing industry would takenotice), she was viewed in far too many Black publics as a trusted arbiter ofBlack gender relations.

JusticeThomas and his advisors clearly understood these dynamics, mounting a responsethat tapped into centuries' old narratives about violence and Blackmasculinity. Thomas's invocation that the hearings functioned as a "high tech lynching" represented a specificgendered reference to racial violence that displaced the reality of genderedand racialized violence against Black women. As Johnnetta Cole and Beverly Guy-Sheftall argue in theirbook Gender Talk: The Struggle for Women'sEquality in African American Communities, for many in Black communities, Thomas, "became yet anotherexample of a Black man targeted by the system presumably for sexual crimes hedid not commit," adding that "Hill could not mobilize the Black community,including women, against a successful Black man for the 'lesser' crime of sexual harassment—even if they werewilling to acknowledge that Thomas was guilty."

Thomas'sinvoking of a "high tech lynching" is also a critical signpost of the emergingdigital era. In his book In Search for the Black Fantastic: Politicsand Popular Culture in the Post-Civil Rights Era political scientistRichard Iton notes that the burgeoning digital era of the late 1980s and early1990 was marked by a hypervisibility of Blackness, tantamount to forms of surveillance. What the Hill-Thomas hearings madeclear was that notions of Black sexual pathology, even amongst middle class figures likeProfessor Hill and Justice Thomas, would be intimately tethered to the newdigital landscape. ABC and NBC'sprime-time coverage of the hearings—on a Friday evening—drew a 40% televisionshare, practically portending the coming of the 24-hour-news cycle.

Theimpact of the Hill-Thomas hearings could be witnessed seven years later, whenBill Clinton's relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky becamepublic. That many viewed such arelationship as a form of coercion on the part of the Commander-in-Chief waslargely due to the ways that Anita Hill's charges against Clarence Thomasaltered the ways mainstream America viewed sexual discrimination and harassmentin the work place.

Notsurprisingly, such resonances were not quickly reflected within some Blackpublics, if we are to gauge responses to Mike Tyson's rape trial and hissubsequent conviction, the R Kelly rape trial and subsequent dismissal, the "TipDrill" protest at Spelman College and the Duke Lacrosse case, whereconventional wisdom placed focus on the culpability of the black women andgirls involved. As politicalscientist Melissa Harris-Perry observes in her book Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes and Black Women in America,these cases "hint at the continuing power of a common stereotype of black womenas particularly promiscuous and sexually immoral," adding that "while the mythof black women's hypersexuality may have been historically created andperpetuated by white social, political and economic institutions, it'scontemporary manifestations are often seen just as clearly in the internalpolitics of African-American communities."

Published on October 16, 2011 21:37

#Occupy The Public Schools? Will #OccupyWallStreet Trigger Movement to Reclaim Our Schools?

#Occupy ThePublic Schools? Will #OccupyWallStreet Trigger Movement to Reclaim OurSchools? byMark Naison | special to NewBlackMan

Yesterday'sGlobal Day of Protest was a milestone in modern history. Demonstrationsin support of Occupy Wall Street took place in more than 950 cities around theworld, with more than 300,000 coming out in Madrid, and 100,000 in Rome. In the US, demonstrations and marches took place in more than 240 cities. Youngpeople in the US, watching the news, listening to the radio, or evenseeing first hand what was going on in their neighborhood, or theircity's downtown business district, couldn't help but be aware that there was aprotest movement taking place that involved many people their age and that themood of these protests was alternately defiant, festive and joyful.

Butwhen Monday comes around, will there be any discussion of these events in ourpublic schools? The Occupation movement would be a perfect subject for classesin History or Social Studies. It could involve discussion of the globaleconomic system, the impact of the current recession on employmentprospects for young people, the history of social justice movements, the roleof young people in movements for social change and many other importantissues. It could allow students to connect what is going on intheir own lives to historical events, something which any teachers knows is agreat way to get students excited about studying history.

Butgiven the pressure put on students teachers and principals to register highscores on standardized tests, there is little chance of this happening unlessthese constituencies join together in a mini-revolt. The way current socialstudies curricula are set up in most public schools, virtually every day isdevoted to some form of test prep, and since teachers and administrators jobprospects are increasingly determined by results on those tests, littlerisk taking can be expected in opening up classes to free discussion .

Orcan it? Could this be the moment that teachers say ENOUGH IS ENOUGH andactually teach about something that students are interested in, and which openup avenues for students to become critical thinkers and social activistswho think they have the power to make history.

Wehave seen hundreds of thousands of people in the US, during these past weeks,overcome their fears and apathy, to step forward and protest against aneconomic system that has left large portions of the nation's population withoutemployment, without security, without hope. They have marched, theyhave chanted, they have camped out in the cold and rain to make their point.And they have prevailed in the face of police violence, and threats of evictionfrom the spaces they have gathered, to build a movement that grows larger everyday.

Perhapsthe same thing can happen in our schools. Perhaps teachers, students andparents can step forward and demand that schools make standardized testssecondary, that they set aside time for students to discuss issues of the day,that they give students outlets to express their thoughts, and over time realinfluence over what goes on in their schools.

The#OccupyWallStreet movement has marked a new phase in US and WorldHistory. The Global Economic system is broken and those of us ineducation must adapt to the times. This is the moment to begin transforming ourschools from centers of obedience into center of critical thought and actionthat will allow young people to participate in the greatest change movement ofthe 21st Century. They have little to lose The tests that are beingshoved down their throats prepare them for jobs that no longer exist. It's time to tell them the truth, let them draw their own conclusions, and takeactions they deem appropriate

Isn'tthat what education is supposed to be about. To give students confidence inthemselves and the power to make positive changes, not only in their own lives,but in the lives of those around them.

TheRevolution in our nation's classrooms can begin Monday. It's time to"Occupy Our Public Schools"

Teachers,students, and parents, are you ready?

***

Mark Naison is a Professor of African-American Studies andHistory at Fordham University and Director of Fordham's Urban Studies Program.He is the author of two books, Communistsin Harlem During the Depression and WhiteBoy: A Memoir. Naison is also co-director of the BronxAfrican American History Project (BAAHP). Research from the BAAHP will bepublished in a forthcoming collection of oral histories Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life From the1930's to the 1960's.

Published on October 16, 2011 07:06

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.