Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1046

November 13, 2011

Transforming Juvenile Justice in California

from the Ella Baker Center

Our youth prison system is broken. It's expensive and it doesn't help our youth. Community-based programs have been proven to work in other states and California's youth deserve better.

ellabakercenter.org/booksnotbars

Published on November 13, 2011 15:10

Deconstructing the 1%: Are the Koch Brothers Denying Your Vote?

from Brave New Foundation

Through their web of political influence, billionaire political operatives Charles and David Koch have bought access to democracy's lifeblood: free and fair elections. The Kochs have funded efforts to thwart 21 million Americans from voting and Koch dollars helped write and propose voting suppression bills in 38 states.

Published on November 13, 2011 09:43

November 11, 2011

Alondra Nelson: The Black Panther Party and Health Care Equality @ Vanderbilt University

from Vanderbilt University

Watch video of Alondra Nelson, associate professor of sociology at Columbia University, speaking Nov. 8.

Typically associated with the revolutionary rhetoric and militant action of the Black Power movement of the 1960s and 1970s, the Black Panther Party did significant and lesser-known work pursuing equality in the health care system. Efforts included a network of free health clinics, a campaign to raise awareness about genetic disease and challenges to medical discrimination.

Nelson, the author of Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination , discusses the legacy of this advocacy as well as the relevance today in the campaign for universal health care.

The talk was sponsored by the Center for Medicine, Health, and Society.

Published on November 11, 2011 19:18

Permanent Markers: Race & The Cultural Politics of Tattoos

PermanentMarkers: Race & The Cultural Politics of Tattoos byLisa Guerrero and David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

We'resports fans. We enjoy most sports,but basketball is really our true love. And typically during this time of year love is in the air. However, with the owners continuing todeny us our NBA (I want my, I want my NBA), we are forced to fill the void withsomething besides more football. Lucky for us, we're also what's known in the postmodern lexicon as "foodies,"so we have been distracting our lovelorn, NBA-deprived hearts with cookingshows. From the more competitiveshows like Top Chef to the voyeuristicand instructional options on Food Network,we have found ourselves watching a lot more cooking shows than normal.

Besides becoming formidable cooks inour own right, our increased viewing of food television programming has broughtto light interesting connections between the masters of the hard wood and themasters of the hard boil. Both arebound together by the shared creativity found in the kitchen and on the court,the competitive spirits, and the emphasis on spontaneity, but it is the prevalenceof tattoos in both worlds that offers a particularly rich perspective on thepopular discursive signs placed on racialized bodies, the continued absence ofclass in the framing of our understanding of pop culture, and the curiouslylinked, yet distinct place of the baller and the chef in the Americanconsciousness of the 21st century.

Inher 2010 storyin LA Weekly: "Chefs with Tattoos: A colorful rebellion against kitchenrules," Amy Scattergood says "Cooks turn to tattoos as a preferred expressionof individualism, a form of rebellion against kitchen environments that demandconformity. For chefs, as forprisoners, soldiers, and NBA point guards, a tattoo is a mark that can be wornwith the uniform." And interestinglist of tattoo aficionados, indeed; all in various ways are linked, albeitdifferentially, to notions of containment and discipline. Setting this differential aside for amoment, it is interesting to consider the sociocultural code of transgressionmapped onto the very literal "markers" of tattoos. Focusing specifically on the popular trending of tattoo artin the late-20th century into the 21st century, theintersecting meanings of rebellion, creativity, and individualism are framedthrough selective lenses depending on whois "rebelling" or asserting their "individuality," and against or for whom.

Chefsdon't typically invoke fear in the imagination of the public at large. Though the contemporary clichésurrounding the "chef narrative" is that they are the "new rock stars," it islargely a romanticized version of professional chefs stoked by theever-increasing fascination with commodified foodie culture, and is reified bya performative rebellion that isn't linked to any substantive notions of danger(unless you count being afraid of a chef spitting in your food). Sometrace this "bad boy" chef image to the emergence and popularity of AnthonyBourdain, whose own performative rebel persona, replete with foul mouth, crankydisposition, heavy drinking, and daredevil attitude toward food cultures, isactually elaborate window dressing for an articulate, thoughtful, passionateand skilled professional.

Thisbrings us back to the idea of the differential relationship to containment anddiscipline of various tattooed populations, and the two main reasons why thecommodified image of the tattooed rebel chef is problematic. First, though it is true that many oftoday's most popular and celebrated chefs have working class, hard-scrabblebackgrounds, the elite training most (though not all) have, and the eliteechelons they have reached professionally setting the palates of mainly moniedclasses, puts their tattooed markings in a very different light than those ofprisoners, soldiers, and NBA point guards, just for example. For the chefs, it becomes a little likedress-up. Meanwhile, their rebelpersonas render invisible the class and labor realities of the line cooks,apprentices, and other kitchen staff who provide the central foundation for thesuccess of the head chefs. Thesebehind-the-scences people, many of whom are also "marked" with tattoos, areactually positioned on the social peripheries that the head chefs play atoccupying. Paraphrasing acommenter on an online story about a reader of Food & Wine magazine being disgruntled by having to see thetattooed arms of chefs on an October 2009 cover: if the tattoos of the head chefs are disturbing, then youdefinitely don't want to see the tattoos they keep in the kitchen. In other words, even in their imagined transgression embodied in theirtattoos, the head chefs remain positioned in a privileged and respected role,unlike their support staff.

Second,not only does the larger social conception of cooking remain gendered in feminizedterms (despite most of the world's most famous and renowned chefs being male),it is also dominated by whiteness, neither of which are attached tosociocultural assumptions of threat. That is to say that a white chef could be covered from head to toe intattoos and never reach the discursive heights of threat and transgression thata black NBA player can reach with just one tattoo. The differential meaningemanating from ink on racially different bodies was evident from the momentplayers started branding themselves in ways that the corporate gatekeepersnever could.

A1997 Associated Press article explained the proliferation of tattoos in the NBAbegan with the following: "Tattoos always have been popular among inmates,sailors, bikers and gang members. Now they're showing up in increasing numbers in the NBA." While noting that 35% of the league hadtattoos (more recent reports put this number at around 75%), the article spendsample time dissecting the tattoos of Cherokee Parks and Greg Ostertag, twowhite players in the NBA who have "goofy" tattoos.

Similarfocus and attention has been directed at Chris Anderson's fully covered bodywith a narrative that depicts him as a free-spirit, a loose cannon, or simplyeccentric. This points to thelarger racial scripts operating through the spectacle of player tattoos. In a brief 2001 article (from the Chicago Sun Times) entitled "Now NBAaction is just tattoos and tantrums," Richard Roeper elucidates the ways inwhich racial scripts and the signifying meaning attached to tattoos operatewithin both the demonization of today's players and the celebration of playersof yesteryear.

InPhiladelphia, coach Larry Brown was so frustrated by his players' attitude thathe took two days off. That did little to alleviate Brown's ongoing feud withscoring prodigy Allen Iverson, who has more tattoos than the average convictand is perpetually surly to fans and the media. (Iverson did nothing to helphis image last year with the release of his homophobic rap album.)

The NBA isback where it was 20 years ago, before Larry Bird and Magic Johnson revitalizedthe game and left it to Jordan, who took it to unprecedented heights. Theleague has more thugs than stars, more selfish whiners than team players.

Morerecently (2009), Kyle McNary lamented the ubiquity of NBA ink in "Tattooshave made NBA almost unwatchable." Arguing that people who get tattoos likely "lack self-esteem"and burdened by "poor decision-making skills," McNary see the NBA's tattooepidemic as indicative of a larger cultural problem within the league: "Basketball,when played right, can be a thing of beauty. But, the two-bit punkattitudes, tattoos and chest-beating has made a great sport look like a thugconvention." The deployment of "thug"is particularly revealing given the racial connotations here, one that pointsto the ways in which blackness and tattoos are a troubling combination in thateach confirms hegemonic stereotypes about black masculinity.

In2000, Allen Iverson appeared on the cover of Hoop Magazine where his tattoos and his diamond necklace wereairbrushed out of sight and out of mind. More recently, controversy erupted when Kevin Durantrevealed that his back and stomach were covered in tats. The sight of Durant, often celebratedas "one of the good ones" (inthis article he is noted to be "likable" and "humble") covered in tatsbrought into question his acceptance into the "good black athlete" club. It further brought into question thecontinued meaning of tats within the primarily black NBA evident not only inthe reaction but in the fact that all of his tattoos are concealed by hisjersey. Eric Freemen reflects on the meaning of his tattoos, their placement,and the changing level of acceptance of NBA tats. Yet, he concludes by arguing that Durant's tats should causelittle to his marketing potential and fan popularity in part because he isdifferent.

It'stempting to say that Durant is trying to hide his tattoos to appeal to a largermarket of fans, but it's possible that he just prefers to put tattoos on historso and not his extremities. Plus, we've reached a point as basketball fanswhere tattoos are not an automatic sign of a thug. They're perfectly normal anda common feature of the league's most popular players. LeBron James is coveredin tattoos, but any marketing issues he has are tied to his lack of achampionship, not the belief that he's a gang member. That point of view isthankfully a thing of the past.

Whatever thecase, Durant's tattoos prove that he's not the squeaky clean figure many peoplemake him out to be. As I've said before, he has an edgy streak. He has a lotmore in common with the rest of the NBA than many people are willing to admit. Itis important to understand that the NBA, as with other institutions within theUnited States, generates competing images of blackness. At one end of the spectrum, we have "'badboy Black athletes" (Collins2005, p. 153) who are consistently depicted as "overly physical, out ofcontrol, prone to violence, driven by instinct, and hypersexual" – they arecommonly depicted as "unruly and disrespectful," "inherently dangerous" and "inneed of civilizing" (Ferber2007, p. 20). In other words,they are consistently imagined as thugs. At the other end of the spectrum arethose players, who "are perceived as controlled by White males" (Ferber 2007,p. 20) and are thus "defined as the 'good Blacks'" (Ferber 2007, p. 20). Tattoos have long functioned as amechanism of designation, a way of demarcating good versus bad, desired versussuspect, marketable versus unmarketable.

JemeleHill writes about the ways in which blackness overdetermines the largermeaning and implications of a tatted body:

The samegoes for appearance. The Denver Nuggets' Chris "Birdman" Anderson,who is white, has so many tattoos that you can barely see his actual skin. Anddespite a troubled past that includes serious drug abuse, he's a fan favoritewho is characterized as a free spirit. But that wasn't the way a lot of peoplefelt about Allen Iverson, whose tattoos and diamond necklace were airbrushedout when he appeared in the NBA's publication, HOOP magazine, in 2000.

Thesight of tatted black bodies, and the association to thuggery, criminality, anddanger is evident here. Here, Hillillustrates the intersection of varied meanings within tattoos depending on theattached body, with race being one element of importance. For many, tatted black bodies signifycriminality, danger, bad role models, thugs, and undesirability. In many ways the demonization andfetishization of tattoos within the NBA points to a larger place of blackbodies within American culture: as demon, as spectacle, as commodity, and asfetish. Yet, it also points to theways in which blackness is imagined as a polluted with the markings of a tattedblack body conceived seen as a visual corrupting body to a pure NBA game.

Inboth the kitchen and the arena, the view of tattoos as infiltrating spacesimagined as at one time pristine and somehow honorable, is a shared myth with verydifferent effects and different racial implications. Today the tatted "rebels" in the culinary world typicallyreceive buzz, accolades, and followings, while the tatted "thugs" on the court typicallyreceive disdain, chastising, and surveillance. It is difficult to deny that the primary difference betweenthe two popular geographies of the chef and the baller is race, which leads usto conclude that while tattoos and race are both permanent markers, tattoos areonly ever skin deep.

***

Lisa Guerrero is Associate Professor of ComparativeEthnic Studies at Washington State University Pullman, editor of Teaching Race in the 21st Century: CollegeProfessors Talk About Their Fears, Risks, and Rewards (Palgrave Macmillan,2009) and co-author of AfricanAmericans in Television, co-authored with David J. Leonard. (PraegerPublishing, 2009).

DavidJ. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Genderand Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written onsport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular andacademic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture,examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popularrepresentations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is theauthor of Screens Fade to Black:Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop(SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan and blogs @ No Tsuris.

[image error]

Published on November 11, 2011 18:35

'Uncovering Race' and Racism in America's Newsrooms on the November 14th Left of Black

Uncovering Race andRacism in America's Newsrooms on the November 14th Left of BlackLeft of Black Host and DukeUniversity Professor Mark Anthony Nealis joined via Skype© by veteran journalist AmyAlexander, the author of Uncovering Race: ABlack Journalist's Story of Reporting and Reinvention (Beacon Press).Alexander, who has worked at the Miami Herald, Boston Globe, National PublicRadio (NPR) and Africana.com, shares her inspirations and reasons for writingher book, and highlights the importance of a diverse newsroom. Neal andAlexander also discuss the ways internet culture and social media have impactedquality journalism and they share the triumphs and pitfalls of thewriter-editors relationship. Alexander uses compelling personal storiesto illustrate the challenges she faced as a journalist. Later, Neal is joined in the Left of Black Studios at Duke University by British filmmaker John Akomfrah. A foundingmember of the Black Audio Film Collective ,Akomfrah's films include Handsworth'sSong (1987), Seven Songs for MalcolmX (1993), The Last Angel of History (1996), Urban Soul (2004), which features Neal as a commentator, and The Nine Muses (2010). Neal and Akomfrah discuss theimplications of migration across the Black Diaspora, the Black Cultural Studiesmovement and go in depth about the contributions of political leaders Malcolm Xand Britain's Michael X's as critical thinkers. ***

Left of Black airs at 1:30 p.m. (EST) on Mondays on Duke's Ustream channel: ustream.tv/dukeuniversity. Viewers are invited to participate in a Twitterconversation with Neal and featured guests while the show airs using hash tags#LeftofBlack or #dukelive.

Left of Black is recorded and produced at the John Hope Franklin Center of International and InterdisciplinaryStudies at Duke University.

***

FollowLeft of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlackFollowMark Anthony Neal on Twitter: @NewBlackManFollowAmy Alexander on Twitter: @@AmyAlex63

###[image error]

Published on November 11, 2011 04:34

November 10, 2011

"I'm a fan of yo' 'I'm Gay'": Fat Joe on LGBTs in Hip-Hop

[image error]

Published on November 10, 2011 19:51

Kevin Powell: Joe Paterno, Herman Cain, Men, Sex, and Power

Joe Paterno, Herman Cain, Men, Sex, and Power

Joe Paterno, Herman Cain, Men, Sex, and Power

by Kevin Powell | special to NewBlackMan

Joe Paterno. Herman Cain. Penn State football. Presidential campaigns. Men. Sex. Power. Women. Harassed. Children. Abused.

These are some of the hash tags that have tweeted through my mind nonstop, these past several days, as multiple sexual harassment charges have been hurled at Republican presidential candidate Herman Cain; as Jerry Sandusky, former defensive coordinator for Penn State's storied football program, was arrested on 40 counts related to allegations of sexual abuse of eight young boys over a 15-year period. Sandusky's alleged indiscretions have not only brought back very ugly and unsettling memories of the Catholic Church sexual abuse mania a few short years ago, but has led to the firing of legendary coach Joe Paterno and Penn State president Graham Spanier, plus the indictments of athletic director Tim Curley and a vice president, Gary Schultz, for failing to report a grad assistant's eyewitness account of Sandusky allegedly having anal sex with a ten-year-old boy in a shower on the university's campus in 2002.

In the matter of Mr. Herman Cain I cringed, to be blunt, as I watched his press conference this week denying accusations of sexual harassment against him, which has swelled to four different women, two identified and two anonymous, for now. I was not there, so I don't know, only he and the women know the truth. But what was telling in Mr. Cain's remarks is that he was visibly defensive and defiant, rambled quite a bit about the media's smear campaign and, most curious, only once mentioned sexual harassment as a major problem in America, and it was just one quick, passing sentence. Then he went back to discussing himself, which he is particularly adept at doing.

What Herman Cain and the disgraced male leaders of Penn State have in common is the issue of power and privilege we men not only wield like our birthright, but which has come to be so inextricably linked to our identities. So much so, in fact, that many of us, regardless of race, class, religion and, in some cases, even sexual orientation or physical abilities, don't even realize what a disaster manhood is when it is unapologetically invested in power, privilege, patriarchy, sexism, and a reckless disregard for the safety and sanity of others, especially women and children.

The question begs itself: Why not? I feel it has to do with how we construct manhood from birth. Most of us boys are taught, basically from the time we can talk and walk, to be strong, tough, loud, dominating, aggressive, and, yes, even violent, even if that violence is masked in tales of war or Saturday afternoon college football games. Without anything to counteract that mindset like, say, that it is okay for boys and men to tell the truth, to show raw emotions and vulnerability, to cry, to view girls and women as our equals on every level, we are left with so many of us, far into adulthood, as fully formed physically but incredibly undeveloped emotionally. And if you are a male who happens to have been sexually assaulted or abused yourself, and never got any real help in any form, highly likely you will at some point become a sexual predator yourself. And if you are a man who still thinks we are in pre-feminist movement America where it was once okay to, well, touch, massage, or caress a female colleague inappropriately, to talk sex to her, as she is either working for you or attempting to secure a job (and has not given you permission to do so), then you are also likely to be the kind of male who will deny any of it ever happened. Again and again and again-

The bottom line is that our notions of manhood are totally and embarrassingly out of control, and some of us have got to stand up and say enough, that we've got to redefine what it is to be a man, even as we, myself included, are unfailingly forthright about our shortcomings and our failures as men, and how some of us have even engaged in the behaviors splashed across the national news this year alone.

But to get to that new kind of manhood means we've got to really dig into our souls and admit the old ways are not only not working, but they are so painfully hurtful to women, to children, to communities, businesses, institutions, and government, to sport and play, and to ourselves. Looking in the mirror is never easy but if not now, when? And if not us in these times, then we can surely expect the vicious cycles of manhood gone mad to continue for generations to come, as evidenced by a recent report in the New York Times of a steadily climbing number of American teen boys already engaging in lewd sexual conduct toward girls. Where are these boys learning these attitudes if not from the men around them, in person, in the media, on television and in film, in video games, or from their fathers, grandfathers, uncles, older brothers, teachers, and, yes, coaches?

For sure, nothing sadder and more tragic than to see 84-year-old Coach Joe Paterno, who I've admired since I was a child, throwing away 46 years of coaching heroism and worship (and 62 total years on the school's football staff) because the power, glory, and symbolism of Penn State football was above protecting the boys allegedly touched and molested by Sandusky. Equally sad and tragic when Mr. Cain's supporters are quick to call what is happening to him a lynching when this man, this Black man, has never been tarred and feathered, never been hung from a tree, never had his testicles cut from his body, never been set on fire, as many Black men were, in America, in the days when lynching was as big a national sport as college football is today. Anything, it seems, to refute the very graphic and detailed stories of the women accusing Mr. Cain of profoundly wrong, unprofessional, and inhuman conduct.

But, as I stated, when our sense of manhood has gone mad, completely mad, anything goes, and anything will be said (or nothing said at all), or done, to protect the guilty, at the expense of the innocent. We've got to do better than this, gentlemen, brothers, boys, for the sake of ourselves, for the sake of our nation and our world. It was Albert Einstein who famously stated that insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result. Then insanity may also mean men and boys doing the same things over and over again, for the sake of warped and damaged manhood, and expecting forward progress to happen, but then it all crumbles, once more, in a heap of facts, finger-pointing, and forgetful memories when convenient.

If any good can come of the Cain and Penn State disasters it is my sincere hope that spaces and movements are created, finally, where we men can really begin to rethink what manhood can be, what manhood might be. Manhood that is not about power, privilege, and the almighty penis, but instead rooted in a sense of humanity, in peace, in love, in nonviolence, in honesty and transparency, in constant self-criticism and self-reflection, and in respect and honor of women and girls, again, as our equals; in spaces and movements where men and boys who might not be hyper-macho and sports fanatics like some us are not treated as outcasts, as freaks, as less than men or boys. A manhood where if we see something bad happening, we say something, and not simply stick our heads in the sand and pretend that something did not happen. Or worse, yet, do something wrong ourselves, and when confronted with that wrongness, rather than confess, acknowledge, grow, heal, evolve, we instead dig in our heels and imagine ourselves in an all-out war, proclaiming our innocence to any who will listen, even as truth grows, like tall and daunting trees in a distant and darkened woods, about us.

A manhood, alas, where we men and boys understand that we must be allies to women and girls, allies to all children, and be much louder, visible, and outspoken about sexual harassment, rape, domestic violence, sexual abuse and molestation. Knowing that if we are on the frontlines of these human tragedies then we can surely help to make them end once and for all, for the good of us all.

That means time for some of us to grow, and to grow up. Time for some of us to let go of the ego trips and the pissing contests to protect bruised and battered egos of boys masquerading as men. Before it is too late, before some of us hurt more women, more children, and more of ourselves, yet again-***

Kevin Powell is an activist, public speaker, and author or editor of 10 books. His 11th book, Barack Obama, Ronald Reagan, and The Ghost of Dr. King: And Other Blogs and Essays, will be published by lulu.com in January 2012. You can reach him at kevin@kevinpowell.net, or follow him on Twitter @kevin_powell

Published on November 10, 2011 13:12

The Tanning Effect: How Dr. Dre And Snoop Dogg Broke Down Barriers (VIDEO)

Last week HuffPost Black Voices premiered the second episode of its ongoing video series, "The Tanning Effect," which featured hip-hop mogul Jay-Z discussing his performance as the first major hip-hop act to headline British festival Glastonbury (in 2008) and the effect of his 2003 hit single, "Change Clothes," on the stock of sports apparel.

In the latest installment of the series, legendary music producer Jimmy Iovine opens up on breaking down barriers with Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg's 1993 single "Nuthin But A 'G' Thang" [Watch the clip above in part two of the interview]. The Interscope Records chairman revealed the trick that influenced radio programmers to play the classic hit on Pop radio stations.

Published on November 10, 2011 05:02

Short Film | Pharoahe Monch "Clap (One Day)"

Starring Gbenga Akinnagbe (The Wire), Kim Howard & Josiah Small.

Published on November 10, 2011 04:52

November 9, 2011

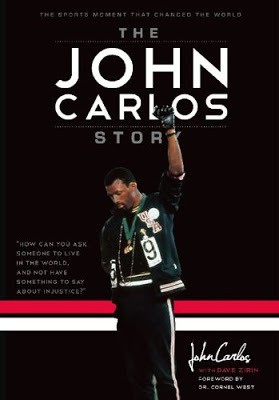

Book Review | The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World

Daring Then, Daring Now: The John Carlos StoryBookReview by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

Havingstudied the 1968 Olympic protest, havingconducted an interview with Harry Edwards on the revolt of the black athlete,and being someone dedicated to understanding the interface between sports, raceand struggles for justice, I was of course excited about the publication ofJohn Carlos' autobiography, The John Carlos Story: The Sports Momentthat Changed the World . Written with Dave Zirin, the book provides an inspiring discussion of the1968 Olympics without reducing the amazing life of John Carlos to the 1968Olympics. More than 1968 or theprotests in Mexico City, it chronicles a life of resistance, of refusing toaccept the injustices that encompass the African American experience.

JohnCarlos challenged American racism from an early age. Readers learn of a young man who "went around Harlem handingout food and clothes like Robin Hood and his merry men in Technicolor" (p. 21). Recognizing the level of poverty andinjustice in Harlem, and refusing to stand idly by, a young Carlos would breakinto freight trains to steal food with the purpose of giving it to those whohad been swallowed up by the system.

Theexperience of stealing groceries and good and giving the people something fornothing was positive. Just doingthis kind of so-called work opened up my mind and got me to notice what wasgoing on around me. I couldn'tturn my back when I saw evidence of discrimination in the community. I captured it in my mind every time Isaw anyone in my neighborhood mistreated by the police (p. 27).

Theseexperiences, like his having to give up on the dream of becoming an Olympicswimmer as a result of societal racism, not only politicized Carlos, but alsoinstilled in him a passion and commitment to help others reach theirdreams. It taught about the powerand necessity of imagining and fighting for "freedom dreams."

The John Carlos Story chronicles the ways he has lived a life guided bythe philosophy articulated by Fredrick Douglas that "power concedes nothingwithout demand." From hisorganizing a strike at his high school against "the nasty slop they called'food'" (p. 33) to his insistence that the manager at the housing protectswhere he lived address the problem of caterpillars in the courtyard, JohnCarlos demanded accountability and justice long before 1968.

Hisbook illustrates the level of courage he has shown throughout his life. When the manager refused to address thecaterpillar problem, which prevented his mother from joining others in thecourtyard because of allergic reactions, Carlos once again lived by the creed:power concedes nothing without demand. John Carlos has lived a life of demanding justice and in the face of refusaldemanding yet again. He describeshis response in this case as follows:

Then I tookthe cap off the can and doused the first tree in front of me withgasoline. Then I reached for a boxof long, thick wooden matches. After that first tree was soaked, I struck one of the stick matchesagainst my zipper and threw it at the tree and watched. It was a sought: the fire just as thattree like it was a newspaper and turned it into a fireball of friedcaterpillars (p. 41).

Thecompelling life that Carlos and Zirin document extends beyond his youth furtherreveals a life dedicated to justice. His refusal to accept the racism and the mistreatment experienced whileliving in Texas encapsulates how America's racism and systematic efforts todeny both the humanity and citizenship of African Americans compelled Carlos'activism as a young man and ultimately as an Olympian.

Theprotest at the 1968 Olympics should not be a surprise given the racial violenceexperienced by Carlos and his brothers and sisters throughout United States(and the world at large). Hisinvolvement was in many ways an organic outgrowth of his life:

I rememberthe moment when I was locked in on the medial stand protest and I knew in mygut that it wasn't just about 1968. It wasn't just about Vietnam, Dr. King's assassination, the murders ofthe Mexican students, or the media tag about some Age of Aquarius 'Revolts ofthe Black Athlete.' It was abouteverything that led up to 1968. Itwas about the stories my father told me about fighting in the First WorldWar. It was about the terriblethings he was asked to do for a freedom he was denied when he returned home. It was abouthim being told where he could live, where his kids could go to school, and howlow the ceiling would be on his very life. I thought about how long ago the First World War seemed tome. It felt, on the other hand,like a time and place beyond my understanding. But on the other, I thought about how similar things were in1968 compared to those long ago days. I thought about a world where I was encouraged to run but not to speak(p. 111)

Thepower and beauty of the book rests with its efforts to contextualize or explainwho John Carlos is rather than simply chronicle what he did in 1968. John Carlos is not an athlete whoprotested at the 1968 Olympics, but a man, an activist, a freedom fighter whochallenged racism and equality throughout his life. The Olympics was one stop in his journey to "Let America beAmerica again."

Yetthe power of the book extends beyond telling his life's story but with its effortsto challenge the ways that the 1968 Olympic protest is used in contemporarymedia discourse. So often used todemonize contemporary athletes or to reflect on the purported conflicts thatplagued Carlos and the other participants, TheJohn Carlos Story pushes back against the continued exploitation of thishistory to advance contemporary arguments. It challenges the sensationalism that has become commonplacewithin our historic memory. Forexample, while much of the historiography juxtaposes Smith and Carlos withGeorge Foreman, who at the Mexico City games carried an American flag in thering, The John Carlos Story takes adifferent tone, focusing instead on the shared experiences (and Foreman helpinghim during a time of need), elucidating the ways in which their constructedidentities as good and bad black athletes are used to control, silence, andstifle protest.

Thepower of the book is made clear in the afterword, where Dave Zirin brilliantlycelebrates John Carlos in relationship to the courage and fighting spirit oftoday's athletes:

As a newgeneration of athletes and activists raise its fist, they can rest in theconfidence that it's been done before, John Carlos dared and continues to dareto more than just a brand. He hasdared to live by a set of principles of great personal and professionalcosts. It's a standard we shouldall aspire toward . . . if we dare(p. 184)

Carloscontinues to dare and inspire athletes and activists alike, traversing thecountry with Dave Zirin, often joining the Occupymovements in various cities. This is fitting since the struggle for justice and equality didn't beginor end in 1968 for John Carlos. The fight continues.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of CriticalCulture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He isthe author of Screens Fade to Black:Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop(SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan and blogs @ No Tsuris.

Published on November 09, 2011 20:45

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.