Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1045

November 16, 2011

Vijay Prashad: Hip Hop Occupies

November 14, 2011 For Heavy D, 1967-2011.

I. We the 99.

"Nobody got more welfare than Wall Street /Hundreds of billions after operating falsely/And nobody went to prison that's where you lost me /But my home, my job, and my life is what it cost me."– Jasiri X, Occupy (We the 99).The students at UCONN invited Jasiri X to headline their "Political Awareness Rally" on November 4. Jasiri is a rapper from Pittsburg, PA., who burst on the scene with his powerful, political music, such as Free the Jena 6, What if the Tea Party Was Black, I Am Troy Davis and most recently Occupy (We the 99). Shortly before he was to come to the event, Jasiri received an email from the Chief Financial Officer of the Undergraduate Student Government at UCONN. The student wrote that Jasiri could perform most of his songs ("they all promote social justice and ending racism"), but the Student Government could not allow him to perform songs "that contain obvious political statements (such as Occupy – We the 99) – as referring to the Occupy movement."

I asked Jasiri what he made of this curious distinction between his other work and the Occupy song. "I do political songs," he said. "How can they say Occupy is a political song and not I Am Troy Davis?" At the event, Jasiri followed Ken Krayeske, who is running for U. S. Congress on the Green Party Ticket. Krayeske made his name through an interview with UCONN's star basketball coach (he asked Jim Calhoun if he'd give back some of his millions as austerity struck the campus, and Calhoun barked, "Not a dime back"). At the Rally, Krayeske invoked Occupy. Jasiri recalls looking out at the students and thinking, "they have got to hear the song." He went for it despite being warned that if he did the song he might not get paid.

Later Jasiri wrote, "At some point in this movement all of us are going to have to make sacrifices, if we truly want to see real change. The 1% control the 99% with promises of money, access, and comfort; we have to put our own souls above all three."

II. Contagious Struggles.

When I asked Toni Blackman, a rapper with the Freestyle Union, what she thought of the Occupy dynamic, she said that it brought her "a sense of relief. I exhaled and thought 'finally.' I believe the energy will be contagious." "Hip Hop is inching closer and closer to the Occupy movement. Soon singing about your riches and your bitches will be less and less acceptable. The Occupy movement has agitated the stagnant air just enough for artists who felt powerless to begin acknowledging their power again."

It is not just the artists. Nor is the contagion going in one direction.

Read the Full Essay @ CounterPunch

Published on November 16, 2011 08:08

Ed Garnes and R&B Artist Anthony David talk President Barack Obama

Ed Garnes, founder of From Afros To Shelltoes , and Grammy nominated singer/songwriter Anthony David discuss President Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, jessica care moore, and using his art as a teaching tool during this special Sweet Tea Ethics @Spelman College.

Published on November 16, 2011 07:53

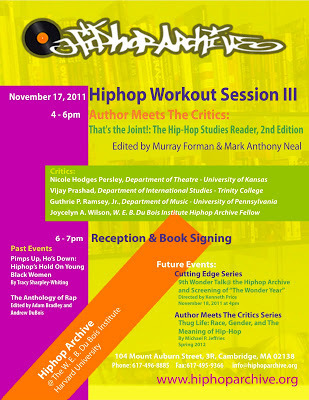

9th Wonder & Mark Anthony Neal at Harvard's Hip-Hop Archive | November 17 & 18

Hiphop Workout Session - Author Meets The Critics: That's The Joint! 2nd EditionThursday, November 17, 2011

Panel 4pm - 6pmReception at 6pm - 7pm

The Hiphop Archive, W. E. B. Du Bois Institute, Harvard University104 Mt Auburn St, 2R, Cambridge MA

Murray Forman (Northeastern) and Mark Anthony Neal (Duke), editors of That's the Joint!: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader (2nd edition)

Participants Nicole Hodges Persley (Kansas), Vijay Prashad (Trinity), Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr. (Penn), and Joycelyn Wilson (Du Bois Institute)

***

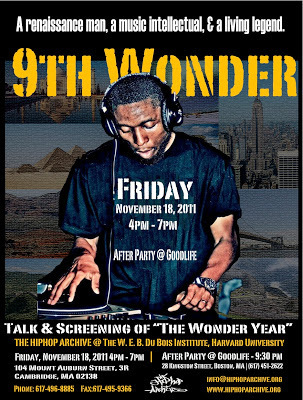

Screening of The Wonder Year (directed by Kenneth Price)Talk and Film Screening with Music Producer 9th WonderFriday, November 18, 2011

4:00pm - 6:00pm

The Hiphop Archive, W. E. B. Du Bois Institute, Harvard University104 Mt Auburn St, 2R, Cambridge MA

Published on November 16, 2011 06:48

November 15, 2011

Open Letter to Mayor Michael Bloomberg of New York

Mary Altaffer/Associated PressOpen Letter to Mayor Michael Bloomberg of New York

Mary Altaffer/Associated PressOpen Letter to Mayor Michael Bloomberg of New Yorkby Kevin Powell | special to NewBlackMan

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Dear Mayor Bloomberg:

I was awakened in the wee hours of this morning by texts and calls from friends and associates distraught that Occupy Wall Street protestors were being forcibly removed from Zuccotti Park in Lower Manhattan. Even more troubling is that you chose to make a mockery of the First Amendment of our United States Constitution by not only evicting the peaceful activists, but also by blocking media outlets from recording the police raid. This is America, Mr. Bloomberg, a nation that through much effort, tears, blood, and, yes, deaths, has evolved from a slaveholding country that also destroyed much of Native American culture, to one where women, people of color, the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community, the physically challenged, Jews, Muslims, White ethnics from places like Ireland and Italy, and so many others have been able to gain some measure of freedom and democracy. We are not the nation we ought to be, yet, but we are also not the nation we once were, either. We do that history, and ourselves, a great disservice when we in leadership positions resort to tactics used to deny freedom and democracy, in the old America of Jim Crow laws, in the old South Africa of apartheid.

As I watched the amateur video made of the raid online this morning, I got very choked up. I am a big supporter of Occupy Wall Street because it speaks directly to my history as a Black person in America. The occupation is nothing more than the bus boycotts, freedom rides, and sit-ins of the Civil Rights era. The nonviolent approach harkens back to the principles of Dr. King, borrowed, of course, from the great Indian leader Gandhi. The use of technology to spread the Occupy Wall Street messages is no different than how W.E.B. DuBois, Marcus Garvey, and other visionaries used the media at their disposal in their day to communicate with the masses. So when we choose to walk down the path of repression, of removing and silencing those who would speak out, Mr. Mayor, we are saying that we are choosing to be on the wrong side of history. That we are choosing to be in bed with the devil, instead of on the side of God, of the noble promises of our America.

But what message are we sending, Mayor Bloomberg, when we come like the thief in the night to remove people by extreme force? What message are we sending when we inhumanly destroy a community built to show what democracy can look like in our era? How condescending and nearsighted are we to state these people are dirty and unfocused, that they somehow are more of a public nuisance than certain banks and corporations that have wrecked the lives of so many Americans? How arrogant are we to assume, just because we may have a certain financial background, status, or title, to think we are above relearning lessons of democracy at various points in our American lives? And how can we ever again say it was not right for militaries in Middle Eastern and North African nations to crack down on the democracies there, then we turn around and do the same on our own shores, only months later, and to our own children, to our own people?

Mayor Bloomberg, you said on your weekly radio show, several weeks ago, that it was inevitable for Americans to take to the streets because of the state of our economy. But is the solution to beat these people back with batons and gloved fists, or is the solution to listen to their voices, hear their concerns, and figure out a way, together, for us as a people, all people, to transform America for these times and beyond?

I know somewhere in your person, Mayor Bloomberg, you have a soul and a moral conscience. You are going to have to ask yourself, billionaire or not, mayor of New York City or not, whose side you are on, because the Occupy Wall Street movement is here to stay, and will only get bigger and stronger when leaders like you attack the protestors, as you've done. Justice, Mr. Bloomberg, is not on the side of those who would misuse and abuse their power. Justice is, forever, on the side of those who would even sacrifice their own bodies because they believe so deeply in their cause. Those are the kind of people and the kind of Americans I stand with, Mayor Bloomberg. Those are the kind of people I know, from their tents, blankets, and makeshift occupied communities, will do for America exactly what those Civil Rights workers did with their shoes, overalls, songs of freedom, and voter registration cards a generation ago. And so it shall be, and so it shall be-

Respectfully,

Kevin Powell

***

Kevin Powell is an activist, public speaker, and author or editor of 10 books. His 11th book, Barack Obama, Ronald Reagan, and The Ghost of Dr. King: And Other Blogs and Essays, will be published by lulu.com in January 2012. You can reach him at kevin@kevinpowell.net, or follow him on Twitter @kevin_powell.[image error]

Published on November 15, 2011 13:19

Mark Naison: Why Bloomberg Had To Attack Occupy Wall Street

Why Bloomberg Had To AttackOccupy Wall Street by Mark Naison | special to NewBlackMan

OccupyWall Street is Under Attack by a huge force while the subways have been closed,along with the Brooklyn Bridge. Here are some key components of the Bloombergpolicies that might explain what the Mayor has to take such extreme measure tocrushDissent:

1)Subsidize luxury housing in Brooklyn and Manhattan and concentrate all affordablehousing in the hyper-segregated sections of the Bronx and East New York.

2)Undermine public education by closing schools over the opposition of parents studentsteachers and community members and replace them with charter schools thatpromote rote learning, obedience and militarized discipline for the children ofthe poor.

3)When a movement finally arises that challenges the Mayor's plan to turnManhattan and parts of North Brooklyn into a city for the wealthy of theglobe at the expense of the city's working class, middle class and poorwho live in the outer boroughs, you close the bridges and subways, bar thepress and crush that movement with Riot Police, pepper spray, water hoses.

Notsince 9/11 have the police of this city been mobilized to this degree.

Andfor what?

Democracyhas been under attack in this city for some time. Now even the illusion ofDemocracy has been removed.

***

Mark Naison is a Professor ofAfrican-American Studies and History at Fordham University and Director ofFordham's Urban Studies Program. He is the author of two books, Communists in Harlem During the Depressionand White Boy: A Memoir. Naison isalso co-director of the BronxAfrican American History Project (BAAHP). Research from the BAAHP will bepublished in a forthcoming collection of oral histories Before the Fires: An Oral History of African American Life From the1930's to the 1960's.

Published on November 15, 2011 13:09

November 14, 2011

Syl Johnson & Numero Group's Eccentric Soul Revue Come to Durham (11/19)

[image error] Numero Group's Eccentric Soul Revue featuring Syl Johnson, The Notations & Renaldo Domino + The Sweet Divines, The Divine Soul Rhythm Band & Horns from D-Town Brass

Saturday, November 19, 2011 | 8:00 pmCarolina Theatre of Durham $25 general • $5 Duke students Buy Tickets

In its flagship series, Eccentric Soul, the Numero Group of Chicago illuminates neglected soul gems through archival recordings and curated performances. This spectacular review reprises a storied tradition from the heydays of Motown and Stax: three vintage soul acts combine with one smoking band for a night of sweat-soaked entertainment.

The 1960s hit-maker Syl Johnson — a magnetic singer to rival Al Green — is enjoying a massive renaissance thanks to the Complete Mythology box set and a string of fantastic headlining performances. Curtis Mayfield protégés The Notations are a Temptations-style quartet with a rich four decade career, and Renaldo Domino is a best-kept-secret with a voice sweet as sugar. With vocal harmonies and backing by the Sweet Divines and their band, the authority and grit of authentic Chicago soul are revived at the Carolina Theatre.

Eccentric Soul Revue is a co-presentation of Duke Performances and the Carolina Theatre of Durham.

Duke students may purchase $5 tickets from the Duke University Box Office or the Carolina Theatre in person, on-line, or via phone.

Tickets to performances at the Carolina Theatre and DPAC are not available as part of a Pick-Four/25% package. However, patrons who purchase a Pick-Four package will receive a 25% discount code good for all Duke Performances' shows at the Carolina Theatre and DPAC.

Published on November 14, 2011 07:38

Syl Johnson & Numero Group's Eccentric Soul Revue Comes to Durham (11/19)

[image error] Numero Group's Eccentric Soul Revue featuring Syl Johnson, The Notations & Renaldo Domino + The Sweet Divines, The Divine Soul Rhythm Band & Horns from D-Town Brass

Saturday, November 19, 2011 | 8:00 pm Carolina Theatre of Durham $25 general • $5 Duke students Buy Tickets

In its flagship series, Eccentric Soul, the Numero Group of Chicago illuminates neglected soul gems through archival recordings and curated performances. This spectacular review reprises a storied tradition from the heydays of Motown and Stax: three vintage soul acts combine with one smoking band for a night of sweat-soaked entertainment.

The 1960s hit-maker Syl Johnson — a magnetic singer to rival Al Green — is enjoying a massive renaissance thanks to the Complete Mythology box set and a string of fantastic headlining performances. Curtis Mayfield protégés The Notations are a Temptations-style quartet with a rich four decade career, and Renaldo Domino is a best-kept-secret with a voice sweet as sugar. With vocal harmonies and backing by the Sweet Divines and their band, the authority and grit of authentic Chicago soul are revived at the Carolina Theatre.

Eccentric Soul Revue is a co-presentation of Duke Performances and the Carolina Theatre of Durham.

Duke students may purchase $5 tickets from the Duke University Box Office or the Carolina Theatre in person, on-line, or via phone.

Tickets to performances at the Carolina Theatre and DPAC are not available as part of a Pick-Four/25% package. However, patrons who purchase a Pick-Four package will receive a 25% discount code good for all Duke Performances' shows at the Carolina Theatre and DPAC.

Published on November 14, 2011 07:38

Black Boys Master the Chess Board

November 12, 2011

Masters of the Game and Leaders by Example by Dylan Loeb McClain | The New York Times

Fewer than 2 percent of the 47,000 members of the United States Chess Federation are masters — and just 13 of them are under the age of 14.

Among that select group of prodigies are three black players from the New York City area — Justus Williams, Joshua Colas and James Black Jr. — who each became masters before their 13th birthdays.

"Masters don't happen every day, and African-American masters who are 12 never happen," said Maurice Ashley, 45, the only African-American to earn the top title of grandmaster. "To have three young players do what they have done is something of an amazing curiosity. You normally wouldn't get something like that in any city of any race."

The chess federation, the game's governing body, does not keep records on the ethnicity of its members. But a Web site called the Chess Drum — which chronicles the achievements of black chess players and is run by Daaim Shabazz, an associate professor of business at Florida A&M University — lists 85 African-American masters. Shabazz said many of them no longer compete regularly.

Ashley, who became a master at age 20 and a grandmaster 14 years later, said the rarity was not surprising. "Chess just isn't that big in the African-American community," he said.

The chess federation uses a rating system to measure ability based on the results of matches in officially sanctioned events; a player must reach a rating of 2,200 to qualify for master.

In September last year, Justus, who is now 13 and lives in the Bronx, was the first of the three boys to get to 2,200, becoming the youngest black player to obtain the master rank. Joshua, 13, of White Plains, was a few months younger than Justus when he became a master last December. James, 12, of Brooklyn, became a master in July.

The three New Yorkers met several years ago during competitions. Justus has an edge over James, mostly because he won many of their early games, before James caught up. Head to head, James and Joshua each have several wins against the other. Justus and Joshua have rarely competed against each other.

Although they are rivals, the boys are also friends and share a sense that they are role models.

"I think of Justus, me and Josh as pioneers for African-American kids who want to take up chess," James said.

James's father, James Black, said he and Justus's and Joshua's parents were aware of what their sons represent and "talk about it a great deal," but tried not to pressure them too much.

Black said his son "knows that the pressure comes along with the territory. What is going to happen is going to happen. As long he plays, we're sure that things will work out for the best."

The three boys approach the game differently. Justus and Joshua say that James studies the most, and Joshua admits he would rather play than practice. "I like the competition," he said. "And I like that chess is an art."

Justus said he is the most aggressive of the three, and he and James agree that Joshua is the most unpredictable. "Joshua likes to change up his openings during tournaments," Justus said.

Supporting the boys' interest is not easy financially. Though there are many tournaments in the New York City area, the boys must travel to play in more prestigious competitions, sometimes overseas. This week, they are set to play in the World Youth Chess Championship in Brazil.

They study the game with professional coaches who are grandmasters. The lessons are expensive — $100 an hour is not unusual — and the boys' families have either found sponsors or have paid for the instruction themselves.

The boys aspire to be a grandmaster by the time they graduate from high school, something that only a few dozen players in the world have done. Ashley, who has met the boys but does not know any of them well, says the obstacles are substantial.

He said several children that he had coached to the junior high school national championships in the early 1990s went on to enroll at elite colleges and then to have successful careers. Along the way, he said, playing chess became less of a priority for them. It is difficult to make a living as a player, he said, adding, "I've seen many talented kids go by the wayside."

Ashley said he could not predict whether the success of Justus, Joshua and James would encourage other young African-Americans to play. Another black teenager, Jehron Bryant, 15, of Valley Stream, N.Y., became a master in September.

"Masters will never be epidemics," Ashley said. He said the rise of the young masters was a "phenomenon" that was " worth noting."

"It is special," he said, "and that we know for a fact."

Justus, Joshua and James all played in the Marshall Chess Club Championship in Manhattan last month. Justus and Joshua finished with disappointing results — a common problem for young players, who often lack consistency. But James tied for fifth. In the last round, he beat Yefim Treger, a strong veteran master who is in his 50s.

Treger is a tough opponent because he uses unorthodox openings. James kept his head, however, patiently seizing space and building up his attack until he was able to force through a passed pawn. He wrapped up the game by cornering and checkmating Treger's king.

Published on November 14, 2011 07:02

November 13, 2011

Bearing Witness: Mahalia Jackson & The Sanctified Bounce

The 7th Annual Mary Louise White SymposiumState University of New York College at FredoniaNovember 4, 2011

Music and Literature: Legacies in HarmonyA Symposium in Honor ofMahalia Jackson's Centennial

Bearing Witness: Mahalia Jackson &The Sanctified Bounce byMark Anthony Neal

The everyday realities of NewOrleans citizens prior to Hurricane Katrina stood in stark contrast toAmerica's view of itself, particualry before the recent finacial crisis. Priorto Hurricane Katrina, nearly 20% of the city's 450,000 residents live below theso-called poverty line. Within theblack community in the city, about 30% of that population was below the povertythreshold, though the national average for Black Americans was about 25%. The nationalpoverty levels for all Americans was 12.7% in the year before HurricaneKatrina. Inotherwords, the black poor in New Orleans–based on a statistical map thatcaptures little of the challegnes faced by those just above the povertyline—represented nearly three times the rate experienced by the average poorAmerican. For those musicanswho toiled in the city and represented its unique cultures nationally andinternationally, their music was often a way to bear witness—to testify, if youwill—on behalf of the city's people and their spirit of resistance. Though the sanitized image of MahaliaJackson, that her record companies Decca and Columbia largely contrived in aeffort to cross Jackson over as a beacon of "Black Respectbility" stood inopposition to the decidely secular, sexual and profane sounds and images of NewOrleans, Jackson musical sensibilities, like many of her peers born and rasiedin the city, always bore witness to its spirit.

The livelihoods of many of New Orleans working classand working poor communities were inextricably tied to their roles as serviceworkers in the tourism industry. In other words, for much of the year, some sections of New Orleans werelittle more than underdeveloped outpost—not of some so-called "third world" nation, but right in theUnited States. As Lynell Thomaswrites, the city's tourist industry "invites white visitors to participate in aglorified Southern past. Blackresidents, if they appear at all in this narrative, appear as secondarycharacters who are either servile or exotic—always inferior to whites and neverpossessing agency over their own lives." Thus perceptions of of the black poor on display at the the NewOrleans Convention Center or in the Louisana Superdome were framed by a nationalimagination that had historically viewed them as service workers or at best,entertainers. In many ways,the coverage of Hurricane Katrina survivors functioned as little more than anational travelogue.

In his essay "On Conjuring Mahalia: Mahalia Jackson,New Orleans and the Sanctified Bounce," scholar Johari Jabir suggest that itwas this very travelogue quality of New Orleans culture that led to Jackson'snow signature performance in the film The Imitation of Life. In the Douglas Sirk film, Jackson isfeatured performing "Troubles of the World," a classic New Orleans funeraldirge. Citing Laurent Berlant's reading of Imitationof Life, Jabir notes that Sirk deliberately framed Jackson's image asgrotesque; the director himself described Jackson as a "large, homely,ungainly" woman when her first witness her at a performance at UCLA, bringingto mind how ineffective Jackson's record was in really controlling how whiteaudiences read her, and indeed it was this grotesque image of blackness writ largethat Sirk aimed to present as a means of highlighting, ironically, blackhumanity in the face of immense tragedy. As Jabir writes, "When Mahalia enters the film with her New Orleansdirge interpretation of "Troubles of the World," we are reminded of that at anymoment, centuries of historically repressed crying, 'weeping and wailing'buried deep in the souls of black folk, could erupt."

In contrast to the kind of natural emotional releasethat Jabir, himself bears witness to, the invocation of New Orleans culturaland musical history in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina was more akin to amarketing plan. In the immediateaftermath of Hurricane Katrina and the failure of the levees in New Orleans,there were many high profiles efforts to raise awareness about the culturallegacy of New Orleans. Many ofthose efforts centered on the exaltation of New Orleans Jazz, with many eventsaimed at providing shelter and support for Jazz musicians dispersed by the tragedy.New Orleans Jazz seemed the most important resource to be protected in themonths after Katrina, more so than the people who made the city such a vitaland important, ever evolving cultural outpost. Lost in the focus on New OrleansJazz—arguably one of the nation's most important cultural exports—are otherforms of musical expression that were and continue to be crucial to thesurvival and spirituality of New Orleans and its citizens, including those whohave yet to return.

ThoughJazz was a critical component of Black political discourse and intellectualdevelopment throughout the 20th century—jazz musicians like JohnColtrane, Billie Holiday, Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln are some of the mostresonate examples of creative intellectuals—New Orleans Jazz is often depictedas being tethered to some imagined past, in which race relations and the powerdynamics embedded in them were far more simplistic. Indeed films like ThePrincess and the Frog and The CuriousCase of Benjamin Buttons and the television series Treme (despite it's progressive political critiques) contribute toa nostalgic view that New Orleans Jazz as a dated, static musical form thatoffers an "authentic" alternative to more commercially viable forms of popularmusic like rap and R&B music. Much of this has to do with the relationship between New Orleans Jazzand the leisure and tourist industries that were so vital to the city'seconomy. In this context,mainstreams desires to save New Orleans Jazz and to protect its musicians areless about strengthening the links between Jazz and Black cultural resistance—aresistance that historically fermented in New Orleans—but maintaining theeconomic vitality of what Johari Jabir calls the "theater of tourism" in whichBlack bodies are rarely thought of as citizens but laborers, servants andperformers.

Inthe introduction to the book, In the Wakeof Hurricane Katrina: New Paradigms and Social Visions, the late scholarClyde Woods places New Orleans Jazz in a much broader context, as part of whatWoods has famously described as a "Blues tradition of investigation." As Woods notes in his essay, "Katrina'sWorld: Blues, Bourbon and the Return to the Source," historically the city ofNew Orleans and the region was "latticed with resistance networks that linkedenslaved and free blacks with maroon colonies established in the city's cypressforests swamps." These traditionsof resistance would manifest themselves after Emancipation and beyond in theform of "societies and benevolent associations; churches, second lines,pleasure and social clubs; brass bands, the Mardi Gras Indians" and of courseNew Orleans Jazz. Two practices also linked to resistance in New Orleans areBounce music and what Jabir again refers to as the "sanctified swing," embodiedin the genres of Rap music and Gospel respectively.

Onepiece of post-Katrina cultural expression that gives voice and presence of thekinds of resistance that Woods highlights is the documentary Trouble the Waters; a film whichtroubles the national memory of places and spaces such as New Orleans. Indeed there's a haunting presence about Trouble the Water, a presence that isimmediately felt by anybody who has had the chance to journey across the cityof New Orleans in the past few years. While tourists travel about downtown New Orleans and the French Quarterblandly commenting on the limitedhours of some of the city's more authentic haunts, and the Lower 9thWard continues to serve as the most lasting monument of the destruction,portions of the city remain a decidedly barren reminder of the vibrant living cultures that once existed in thecity. Of course where there is nopeople, there is no culture and the slow pace of recovery in the city suggestthat something more sinister might be in play. Nevertheless, if Hurricane Katrina offered the rationale forwhat might be the only most contemporary example of ethnic cleansing in theUnited States, then the power of Troublethe Water comes from its brazen ability to summon the voices and spirits ofthose—who by force or choice—have not returned. As such Trouble theWater is a striking intervention, for a city that lacks the bodies—and thepolitical wills that such bodies possess.

Trouble theWatertells the story of Kim Roberts, a 24-year-old New Orleans resident and aspiringrapper and her husband Scott, as Roberts documents their experiences before andafter the hurricane on a hand-held video camera. Produced in collaboration with Tai Leeson and Carl Deal, thevery fact that the film exists speaks to the economic realities of so manyKatrina Survivors. As Rivers toldthe Brooklyn Rail, "We'd run out of money. We had about a hundred dollars left,and we was like, "We ought to try to see what we could do with this tape; wemight find somebody we could give this tape to; well not give it, but eithersell it, or license…you know, see what it's worth." Robert's comments capture the DIY ethic that has informed hip-hopgeneartion expression, but also taps into more traditional African-Americansensibilities that can be best captured in the notion of "make a way out of noway." If we think about survival as distinctly improvisationalmode of navigating in the world, Troublethe Water finds it grounding by harnessing the rhythms of blackimprovisation via Robert's audio and visual narration.

There's a telling scene early in the film, whenRoberts travels the streets of New Orleans alone shortly before the storm and sings to herself"On My Own" in reference to the Patti LaBelle recording. Seemingly a random utterance, thereference would have a particular resonance to African-American audiencesfamiliar with Labelle, who possesses iconographical stature in many blackcommunities. Mirroring thesampling practices of contemporary hip-hop, the film is littered with suchreferences, offering audiences the possibility of gaining greater literacy inBlack New Orleans culture and African-American culture more broadly. In another example the Roberts's familydog is named "Kizzy" in reference to a popular character from thegroundbreaking miniseries Roots. Within black vernacular expression, theterm has been utilized as a metaphor for overburdened black women. In fact, Robert's deployment ofAfrican-American vernacular culture as part of the metaphorical shelter thatshe and her comrades construct in response to Hurricane Katrina helps establishRoberts as the most credible intellectual agent in the film, despite her claimsto the contrary early in the film. Robert's use of black vernacular culture isakin to what Woods more formally describes as the "blues tradition ofinvestigation and interpretation." According to Woods, "the blues began as a unique intellectual movementthat emerged among desperate African-American communities in the midst of theashes of the Civil War, Emancipation, and the overthrow ofReconstruction." More specificallyin the context of Roberts's narration, Troublethe Water, "draws on African-American musical practices, folklore, andspirituality to reorganize and give a new voice to working class communitiesfacing severe fragmentation."

Though Roberts and her husband survive the hurricane,Trouble the Water still serves astribute to those who were lost in the storm and I'd like to suggest the filmserves as a kind of "second line" performance—the parade of dancing, shufflingbodies that occurs, often after a funeral. According to musician Michael White, "at the time oftheir origin, these parades offered the black community an euphorictransformation into a temporary world characterized by free open participation and self expressionthrough sound, movement and symbolic visual statements." White adds that "impositions andlimitations of 'second class' social status could be replaced by a democraticexistence in which one could be or become things not generally open to blacksin the normal world: competitive, victorious, defiant, equal, unique, hostile,humorous, aloof, beautiful, brilliant, wild, sensual, and even majestic." Assuch Trouble the Waters serves as acritical intervention into a national memory that would rather ignore thecultural gifts that New Orleans gave the young country, the dead bodies thatwere sacrificed in the midst of catastrophic circumstances, as well as the possibility of rebirththat the Katrina-Politians—those bodies dispersed by the floods—embody.

Mahalia Jackson knew a great deal about secondlines. According to Jazz historianRobert Marovich, Jackson was "exposed to, fascinated by and, most assuredly aparticipant in the second line of New Orleans Marching and Funeral bands." ThoughJackson came to prominence in Chicago, the legendary Gospel singer was born andraised in New Orleans's Lower Ninth Ward. Jabir suggest that one of the reasons that Jackson is rarely thoughtabout with regards to New Orleans has to do with "the ways the canon of NewOrleans music is recognized exclusively through the lenses of blues and jazz." More importantly Jabir writes, theimpact of New Orleans music on Jackson—what she called "a rhythm we held on tofrom slavery days"—allowed her to bring an element of "swing" (associated withJazz) to the decidedly anti-secular Gospel tradition of the mid-20thcentury.

Usingthe example of Jackson's often-recalled performance of "Didn't It Rain" at the1958 Newport Jazz Festival (for which she was heavily criticized by the "truebelievers"), Jabir suggest that Jackson's performance of the song anticipatesthe Hurricane Katrina disaster that occurs more than thirty years after herdeath. Jabir is not so much suggesting that Jackson had the capacity to tellthe future—though the history of the region might suggest otherwise—but thatthe "sanctified swing" that marked her music and others like Duke Ellington (orWynton Marsalis if you listen to In ThisHouse, On This Morning) is "a heartbeat, a pulse driven by a persistentrhythm" adding that "if music were a living organism, the pulse would hold themusic steady, sustaining life inthe midst of various rhythms." Ultimately, according to Jabir, Jackson'sperformance of "Didn't It Rain" isa "tenacious hope that finds the singer describing the disaster, accepting it,and living in spite of it"—a gift to those who would come well after Jacksonwho could grab hold to the "sanctified swing" when faced with their ownsurvival.

Marovichoffers even more distinct connections between Jackson's New Orleans roots orroutes, if you will, to sample a bit from political scientist RichardIton. Marovich specifically fivesuch examples in the "Rhythmic Pulse or "bounce" of Jackson's music, her use ofthematic variation and impr0visation—what Amiri Baraka has classically calledthe changing same, Jackson's mode of attack—accenting the first note the way ajazz trumpeter might start a solo, the physicality of her performance, akin tothe frenetic energy she witnessed during second-line celebrations, and finallyher trafficking in black southern church vernacular.

Evenless regarded by the mainstream consumers of New Orleans music is rap music, asmost popularly represented by figures such as Lil' Wayne, Juvenile, Master P,Mystical and others. Yet Woodssuggest that even Hip-Hop culture in New Orleans is an articulation of the"Blues tradition of investigation"particularly in the form of the regionally specific genre of Bounce music. TheNew York Times recently chronicled a contemporary strain of Bounce known asSissy Bounce, though the genre's roots go back to the late 1980s. It was the 1990song "Where Dey At" by MC T. Tucker that helped give the style some prominencebeyond New Orleans. Woods connectsBounce to earlier forms of New Orleans musical expression, as harkening back to"critiques of the plantation bloc found in the Calinda song and dance traditionperfected on Congo Square [the "birthplace" of Jazz] during the 18thcentury.

Inher essay, "'My Fema People': Hip-Hop as Disaster Recovery in the KatrinaDiaspora" Zenia Kish pushes the connection between Bounce and New OrleansHip-Hop more explicitly. As Bouncecreated an autonomous New Orleans based riff on Hip-Hop, it informed Hip-Hop'sresponses to Katrina including Mia X's "My Fema People," 5th WardWeebie's "Fuck Katrina (The Katrina Song)" and The Legendary K.O.'s now famous"George Bush Doesn't Care About Black People." Though mainstream rap artists like Jay Z, Lil Wayne, KanyeWest, Mos Def, and Juvenile ("Get Your Hustle On"), offered responses to Katrina,Kish suggest that tracks like those from Mia X and 5th Ward Weebieoffered a "collective first-person perspective" of the "frustrations,humiliations, and pleasures grounded in specifically local knowledge of themultiple socioeconomic disasters that intersected with Katrina."

Published on November 13, 2011 19:33

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.