James F. Richardson's Blog, page 2

March 29, 2025

The Modern Cruise Experience Will Exceed Your Snarky Expectations

An essay for normies…not twits…

Harmony of the Seas- AquaTheater -Aft

Harmony of the Seas- AquaTheater -AftThe modern literary writing corpus on the cruise ship experience is as needlessly voluminous as it is awful in tone. The authors who write these sarcastic, holier-than-thou missives make no attempt to see the experience from the inside. Not the slightest attempt. That would require good faith interviewing. And research. Such bother.

But the real problem with this homogenous genre stems from the fact that the authors are the least predisposed possible cruisers; male individuals who attend as singles against their lifestyle instincts and, then, shockingly, discover the most suspicious of findings: they were right all along in their disgust.

Their predetermined finding, which I also shared for most of my adult life, is that the cruise ship is “Vegas at sea.” Not the gambling so much as the focused desire for maximum hedonic bliss per calendar day. Excessive drinking. Screaming. Whatever a highly introverted, over-educated, misanthropic ‘writer’ can not in any way personally relate to - going alone into a large crowd and ‘working it.’

I have read David Foster Wallace’s piece - a supposedly fun thing I’ll never do again https://g.co/kgs/fQUPwGV. And, more recently, the much more self-indulgent whining in a 2024 “whin-ary” by Gary Shteyngart at the Atlantic (I refuse to cite this disingenuous piece even though I am a subscriber).

There is a truism where I come from in cultural anthropology- with our small sample sizes and limited access, you should favor the insider point of view with minimal critique. You don’t swoop in with elitist criticism resting on bullshit empirical foundations. You take the side of your audience and perceive things as best as possible from their point of view.

So, here are my ‘trenchant’, empathetic and honest observations as a good faith, paying cruise ship attendee on board with my family for a week on Royal Caribbean’s Harmony of the Seas.

We had mediocre expectations but wanted to be surprised.

1) The Bubble Within the Floating Bubble

It’s visually obvious that a cruise ship is a self-contained world. Look at the thing. It’s also a fully resourced social bubble supplied with everything it needs for the entire voyage. Virtually no ships onboard anything at ports of call. Not even water or fuel! Royal Caribbean (RCL) does not set sail and run out of fuel at the second port like your ADHD Uncle ran out of gas on that famous, multi car family vacation in ‘93. Nope. Royal Caribbean and most cruise lines forward buy their diesel using a business process called “hedging.” And they store it at their massive source terminals.

Yet, the most interesting thing about cruising I can ascertain is that most people overwhelmingly book in groups. Singles are a radical minority. And everything on board works towards ending any temporary alienation. In the U.S., only 10% of passengers are traveling solo.https://cruising.org/-/media/clia-media/research/2024/2024-state-of-the-cruise-industry-report_updated-050824_web.ashx

The preponderance of groups involve families, family reunions, grandparents plus kids plus grandkids, college friends, post-college girlfriend groups, you name it.

Cruise ships are ironic vestiges of all ages group fun in a world where youth culture and the labor market have estranged grandparents from their grandchildren, older generations from the youngest.

Yet, the mostly two-person staterooms allow everyone a bubble to retreat to from their de facto group. Your tiniest bubble could be solo or duo.

You can scale up and scale down your group socializing on demand very easily. The ship is designed to allow lots of hiding and lots of manic engagement. And without the cross-town trips a normal urban vacation would require to accomplish this.

This does not happen by accident. I’m sure it was designed this way, though these ships appear to be more simplistic in design than they actually are.

2) Masters of Inclusion

Honestly, as an introvert, I feared most the potential for sensory overwhelm and extroverted suffocation as I boarded. So did my wife. But, Royal Caribbean’s megaships are masters of design for sensory inclusion.

The rooms are so incredibly soundproofed, we could not hear our boisterous teens through the adjoining wall, only when we stood right next to the door. So, the quiet introverts can easily retire to their staterooms for a nap or quiet time and recharge. We do this at home all the time, but intentional ship design is crucial to making this happen. The large ships are also amazingly ADA accessible, far more than your average hotel property.

RCL also manages to have onboard music everywhere at just the right genre and volume to motivate ‘action’ and with omnigenerational music (not easy). But, if you want to walk around with airbuds in, no one will stop you.

In the 18+ Solarium, there is only ethereal instrumental music playing. It’s basically Enya to the max. Perfect for talking and reading. Lots of adults reading here. Young introverted couples also hang out here. It’s never been full except the first afternoon (when no one knew how to make use of the ship).

In the Aft you find loud hip hop and popular music booming to keep those 3-17 year olds moving (and exhausted later!) on water slides, Flowrider venues and in the splash pools.

The two sound zones never mix. At all.

There is also enough culinary diversity inside every dining venue’s menu to satisfy a newer, multicultural, beyond-steak-and-potatoes crowd. The specialty dining charges a steep premium for culinary snobbery, as it should. We did it twice!

See Figure 3 for the bizarre, lushly landscaped row of specialty dining venues on our ship. We even got our kids to wear pants, which is a miracle for any parent who lives in Tucson. Pants?!

Figure 3 - Specialty Dining That Does Not Fail

3) Reliable Hospitality

Prior to boarding, I had assumed that real hospitality from energetic, motivated staff was pretty much dead in my lifetime outside of $500 a person restaurants. My expectations are that low today in the U.S. restaurant world. Management treats these folks so poorly on average that it’s a miracle wait staff can even muster a smile at your average sit down restaurant (I.e. Applebee’s). And the folks that used to provide amazing table service have far more lucrative job opportunities in their 20s and 30s. Usually.

As I correctly hypothesized before boarding, RCL at least operates at the standard of Disneyland when it comes to hospitable staff. Seriously, better than Disneyland.

I realize that the U.S. Cruise ship industry depends heavily on foreign crew and staff. Thank God they do! I would pay double for what we received in terms of service.

For the first few days, I struggled to understand how RCL pulls it off beyond its own incentives and work culture. Then, it hit me, the vast majority of the staff you encounter are from the Philippines, India and SE Asia. These are cultural worlds where hospitality, including faking it well, is an ancient art form and a source of high social status. Being very hospitable is how you perform elite status in the countries. It’s how you distinguish yourself from the ‘rude villagers.’ Rude, obnoxious people can succeed in America because we are hyper-individualistic and reward non-hosting professions so well. Just look at Elon Musk for a prime example.

Modern cruise ships may offer the best behaved staff of any possible vacation scenario for a well-heeled American.

I have seriously seen only one depressed staff person (who may be in the wrong industry?)

This is critical, not because the average guest is an entitled wanker but because you have to interact with so many staff people in a service-dense cruise environment. You would go crazy if they all had the attitude of a local diner waitperson (who should be depressed BTW).

4) Remarkable Attention To Detail

No. Not a throw away header. Let me share but one of many design elements that reflect nuanced thInking. Push button bathroom doors on the top decks (i.e. open to the wind)

On the lower right of Figure 1 - notice the open door button. I’m guessing this is an ADA feature, yet it is NOT marked as such. And, when at sea, you discover how hard it is to open these swing doors with a) AC suction from the inside and b) 20 knot winds outside keeping the door shut. Hard even for an adult who lifts weights. After yanking on the door twice, I converted to push button open (from both sides)! Another example of inclusion as well for the elderly and kids. I did not stand there to count, but I did see kids struggle with these massive metal doors. Until they found the buttons with their Gen Z technophilic vision.

Figure 4 - Exterior Bathroom Doors w/Push button opening

Other examples included: showers preset to a comfortable, not-hot temperature with a simple rotating tab, very high quality beds, stateroom cabinets/shelving that does not bang and clang, carpeted double stairwells with gorgeous art to invite you to walk up/down 2-3 floors instead of clogging elevators, and on-demand soft serve ice cream cone stations for nine hours a day near the kiddie zones!

Cruise ships are probably the most well thought group spaces in modern civilization it would appear. Why can’t our local governments match this standard?

5) Disney-grade hygiene

The number one stigma of cruise ships among my upper-middle-class set would be - “They must be filthy! Norovirus! Ahhh!”

And yet, nothing could be further from the truth. Not since Disneyland have I seen so many staff constantly, and I mean constantly cleaning…everything. The sun decks. The pool decks. The bathroom floors. The buffet dining areas. The interior carpeting. The everything.

Just when you notice dirt and want to find someone to inform, he-she appears. Feels like magic but it’s just a product of detailed planning and service intervals.

They are so good at just-in-time cleaning on our ship that you can not leave your buffet table for even 10 seconds or your dishes will be collected! Only happened once to us though. Do. Not. Fuck. With. The. Cleaning. Not sorry.

Figure 5- Nonstop Cleaning

The key standard they observe on RCL and similar ships is to train staff to look for filth and jump on it. The use of lithium battery-powered cleaning packs is genius because it has eliminated cord tripping by guests!

And, they have hand washing stations at the entrance to ALL the buffets!

Figure 6- Nurse-approved hand washing stations!

I can’t understate the hygiene joy I experienced when coming onboard with very low expectations (of me hiding in my stateroom out of filth terror).

Epilogue

My wife was the most nervous about the crowds, filth and sensory cuckoo we might find on a ship housing 6,000 plus guests and 2,500 staff. Yet she has converted so hard to cruising, that we spent time in the RCL sales office on board exploring a Japanese itinerary! True to the marketing savvy of cruise ship companies like RCL, the sales office is called Next Cruise, not “Sales.”

For families today where you want to multiple rooms for privacy between you and your kids, the value per person per night of modern cruising is hard to find anywhere else.

Modern travel with individualists is annoying and stressful and prone to argument because every element, every move, must be planned to incorporate divergent preferences. Every day is a battle over meals, destinations, timing.

PITA.

A modern cruise ship allows your group to segment as needed according to its individuals’ preferences and reform when preferences converge. Miracle!

All you do is select from a short list of curated options. It’s called forced choice in survey design. Ironically, it forces productive family coordination and increased group dining, something lost from many households in America today.

Don’t believe the misanthropes.

March 15, 2025

No, Most of You Would Not Last Six Months Living Abroad - Part 2

You will be corrected often after you become fluent and trusted…

You will be corrected often after you become fluent and trusted…Like several million kids in my Gen X cohort, I grew up listening to Curious George at bedtime. Not once did I find it odd that I admired a smiley monkey who stole, broke, and vandalized things….all for the sake of public art. (The floating newspaper boat parade was pure genius).

George was excessively curious, and it generally got him in trouble on a routine basis.

Curious George is a very American archetype of the rule-breaking entrepreneur, artist, and activist with a ‘good’ objective. His curiosity gets the better of him, but he is forgiven. And, so, the curiosity gets rewarded. Most kids identify with the rebel side of George very quickly, partly because they wish they could break all of Mom and Dad’s annoying rules, too. [Kids also like rebels because kids are society’s most disempowered age group].

I fear that more kids take away the American rebel theme from this iconic series than the theme of unwavering curiosity.

And it is curiosity that ultimately determines how well you adapt long-term to a foreign culture. Not IQ. Not money. Not even language fluency. Language, after all, is just a tool. It takes curiosity to suffer through the language learning process.

In last week’s piece, I discussed how learning a country’s native language is critical to building normal, high-trust relationships with local people. Without some fluency, you can not enter local social networks (except through marriage) because they will never fully trust you. In many cultures, lack of fluency will mark you as “stupid,” even if you appear well off. This is very true in the U.S.

However, gaining access to social networks through fluency is one thing. Once you gain access to proper relationship formation (i.e., friendships), the awkwardness and complexity of crossing a cultural boundary ratchet way up.

Things get more challenging for you, not easier.

The first nine months I lived in Tamil Nadu in 1997, I was in an American-backed language institute, where we spoke too much English during class, ate breakfast and lunch with Americans, and you get the picture—too much of an expat bubble. Most students did not intend to become orally fluent (they often intended to study Asian literature or history).

As I mentioned in last week’s piece, it took me over a year of hanging out on the streets at night to develop my conversational fluency. It sucked speaking Tamil like a drunk, stammering four-year-old at first. But I persisted, staring at the long-term objective of social access in front of me. And the language fascinated me, honestly. It makes your brain think differently. Speaking Tamil will change your personality.

After nine months at the American Institute for Indian Studies, I returned to the U.S. to obtain my research visa and then flew back to begin fieldwork.

After returning to Tamil Nadu, I was totally alone, renting a house inside a local suburb with no other foreigners. No more daily temptation to speak English. No more expat lunches. And, in six months, I became really depressed. My atypical neurology aside, part of the issue that confronted me (and anyone else who gets to this point living abroad with fluency) is that local people are now criticizing and correcting you as a local and at a furious pace. And yet your relationship with them is not super deep yet either. But much deeper than any tourist will experience.

Part of you will want to scream, “For crying out loud, I just got here!!!”

And, because you are linguistically competent but still culturally incompetent, you will be getting quite an earful. There is no real way to avoid this transitional awkwardness as an immigrant. And, ironically, your admirable fluency is what has earned you this ‘prize.’ More trust in you means locals now evaluate your behavior as if you were a local, not a silly tourist (i.e., a walking bank account from whom to extract the maximal amount of cash).

This period of maximal awkwardness is when your intrinsic level of human curiosity will either save you or send you rushing to the nearest international departures lounge. This happens even to graduated students.

Here’s one example of where something fundamental gets screwed up by Americans all the time where I lived in India.

The Art of Saying Goodbye in Tamil CultureI want to use a straightforward human behavior to illustrate how living abroad is about more than language fluency. It is about understanding more subtle codes and values. These codes are the beating heart of human cultures, if the concept has any analytical value.

Tamil speakers use a verb compound, a phrase, to say “goodbye” to each other. They do not use the dictionary translation for the English word “goodbye.”1

“வரேன்.”

It literally means - “I’m coming.” It is only one word, because spoken Tamil uses verb endings to indicate the subject, so pronouns are optional. Very efficient.

And this word is short for the “schoolyard” Tamil version of goodbye which I often used-

“போயிட்டு வரேன்.”

Denotatively, this formal phrase translates as “I’m going and coming.”

If you’re confused, welcome to Tamil Nadu, where people ensure you know they are “returning” as they depart your presence.

Why is THIS so polite in Tamil culture? It signals that the relationship between you and your audience is highly valued. They value it, so they want to signal their return, i.e., this relationship continues. Leaving a conversation at a coffee stall or someone’s home requires you to validate the status of the relationship at a minimal level. That’s how important relationships are in Tamil culture.

If you ever say something Americans routinely say, “I’m going now,” or if you think “goodbye” and say the Tamil verb for “I’m going” as a substitute (very common mistake), you’re not signaling what you think you are.

“I’m going” in Tamil is an utterance that breaks a relationship. It is the language of estrangement. It is incredibly disrespectful if you use it with a parent or other family elder. It is a verbal slap.

Instead, Tamils saying goodbye to a friend or loved one or respect person, always say “I’m coming.” It means - “I’m coming back for sure. We’ll talk again soon.” But it does this in two phonemes using one present tense verb.

This level of linguistic efficiency and deep coding is shared only among classical world languages, most of them being Asian languages, born of cultures accustomed to incredibly nuanced relationship management and advanced social skills. You will not find it in English, but someone is welcome to challenge me here.

From a Tamil point of view, American English speakers saying “goodbye” routinely dishonor their closest relationships with sloppy language. That’s because we rely on a departing hug, a gesture, to really indicate the relationship’s value. And not always.

Does it matter if you use language or gesture to validate a relationship that matters to you?

Yes. I’m going to say it does in human cultures. Because disrespectful language is rarely forgotten when deployed. Saying “I’m going” is just rude in Tamil culture in a way it is not in American English. 2

No one in Tamil Nadu will forget someone who says the following to them, often in a disgusted tone,

Rough translation: “What kind of person are you (disrespectful form) My God! You useless fool. I’m outta here.” Notice how many fewer phonemes it takes (in my recording) than in English to tell someone to ‘fuck off’ without swearing.

An American hug can be perfunctory. Who knows what it means?

But telling your friend “I’m going” won’t be ambiguous to her. Nope.

Why Curiosity Matters in Adapting to Foreign CulturesYour reaction to being corrected for a social faux should be, “Wow. That’s fascinating. I won’t do that again, sure.” You must treat the local culture like a dynamic puzzle you need to decode. Then, your curiosity accelerates your learning because mistakes become a positive learning process.

If you see faux pas abroad as humiliating, annoying, and frustrating, you won’t be staying very long. Your inner “George” is probably dead. You simply do not have the muscle to adapt. Even if you are fluent, you may still leave.

Most who try to live abroad fail to meet this crucial curiosity test, in my experience. Whatever curiosity they have is not enough to withstand being culturally incompetent like a child—the constant corrections.

You have to be comfortable with a lot of awkwardness. A lot.

1

1This word is highly formal and I only heard it used at bureaucratic functions by VIPs.

2The one vestige of this kind of relationship emphasis in English is found in using informal phrases like “bye” or “see you soon” instead of “goodbye.” The latter is pretty formal and dose signal the relationship is either formal/hierarchical or just plain weak.

March 8, 2025

No, Most of You Would Not Last Six Months Living Abroad - Part 1

Wait! I have to really learn to speak French? Like, for real?

Wait! I have to really learn to speak French? Like, for real?In the late 1990s, I lived in India for nearly three years, studying Tamil and conducting immersive field research in a large temple city. I never intended to settle there, and my opinion did not change before I left. I was happy to return to the U.S. in December 1999 and end my voluntary celibacy (i.e., only white women had free, safe sexual ‘options’ in conservative Indian towns back then, and I watched them pair off repeatedly!).1

South India in 1997 was a highly unfavorable space-time target destination for an upper-middle-class American single male. Just about everything was working against you. At the time, I viewed it as a monastic boot camp, akin to a Catholic missionary living at a fur trading outpost in 18th-century Illinois. My intent in going to such a cultural place was not to have “fun.” I went there to learn and explore. Curiosity was my primal intent.

Ironically, settling in India to work made it significantly easier to adapt. I expected it to be arduous. And I had considerable incentives to generate goodwill. Curiosity also made it easier to swallow the many minor humiliations of being culturally incompetent.

Overall, I give myself a B for adopting local norms—I did enough to avoid being driven out of town by a mob and sent packing to the Chennai airport. But I pissed people off with American moves and assumptions. Absolutely. I was not incentivized like an actual immigrant.

How Fluency Yields Social AccessIf there’s one piece of advice I can give anyone considering resettling abroad, it is this: treat it like Basic Combat Training. The first ‘test’ in your training is becoming fluent in the local language. You will tire of being treated like a tourist without passing the language test. Then you’ll have to decide between loneliness or hanging out with the jingoistic Americans of your choosing (often your American expat colleagues). You’ll be trapped in a tourist-heavy, English-speaking limbo that loses its charm quickly. Rick Steves’ admonition to interact with local people with some tourist speak is nice for a two-week vacation, but does not make you any friends. Sorry. Rick has bilingual friends all over Europe because he revisited the same places dozens of times as work—an irrelevant data point.

If you think being a couple helps you withstand your linguistic isolation, all I can say is that you would need to be a very ‘special’ anti-social couple to put up with this level of disconnection—the kind who reads books all day long in retirement. You won’t last more than six months before one of you becomes severely depressed.

You do not need to be able to riff slang with the local teenagers, although that is a fantastically useful standard to set for yourself. You would impress everyone if you can achieve that degree of adult fluency. But you need to be damn good conversationalist within two years at least. That’s your deadline. Ready?

Learning a local language well is not about permitting interpersonal communication. It’s about signaling trustworthiness to local people. If someone can not fluently converse with you, how can they pretend to know you? That’s why a language barrier prevents deep trust formation. Humans need language to probe each other’s origins, values, motivations, etc.

It’s shocking how much you can communicate with basic hand gestures and facial expressions across any language barrier. I could have even done most of my Indian fieldwork by speaking English and supplementing where necessary with an interpreter. Easily. But this would have killed my access to people’s real lives and feelings. The interviews would have sucked. It would have vastly reduced local trust in me.

One of my local friends once told me, “People only tell you things because they respect that you learned Tamil, James. Otherwise, they wouldn’t tell you anything.”

The correlation between verbal fluency and trustworthiness is one of the least discussed aspects of moving abroad to a non-English speaking country. Even when many educated locals in your destination country know English, refusing to learn the local, dominant language will still prevent them from giving you access to their lives. Popular travel shows orchestrated between media networks and local ‘experts’ give a false impression of how easy it is to access local social worlds with English. You won’t get far beyond the most transactional forms of retail or government offices. Even most of the fluent English speakers will keep their distance.

The inescapable link between fluency and social trust is no different for a new immigrant to America. One of the most disabling features of being a working-class, poorly educated, non-English speaking migrant to the U.S. is that you will gravitate very quickly to a community/neighborhood/social network that enables your ongoing inability to learn English. Not great for your income.

For an immigrant to America, acquiring English fluency is more powerful than anything, save a college degree, when it comes to opening up opportunities to generate real income and provide for yourself. The alternative is an ethnic trap.

Believe it or not, even the most globally curious American reacts differently to immigrants fluent in English (with an accent) versus those who can not string a basic English sentence together correctly. I am not here to encourage snobbery or judgment. The dark truth is that we tend to assume the poor English speaker is stupid or even a bad faith person who does not care about fitting in. Americans are unusually prone to these flawed assumptions because most of us are not bilingual.2 We have not been through the second language acquisition process, and have no idea what is involved cognitively and emotionally.

How I Became Conversationally Fluent in Tamil in 18 Months - Ready to Do This?If you think you want to resettle abroad, read about how I gained verbal fluency in Tamil. Are you ready to do this…

Never one to shy away from an absurd goal, I gave myself a year to become fluent in Tamil in time for my fieldwork. It took six months longer than this primarily due to the total lack of structural overlap between English and Tamil. “Street Tamil” also varies massively from written Tamil, more than the English language crossing from written to spoken word.

I had already spent two years studying the language in the U.S., where I also supplemented course work with vocabulary cramming. Anyone who knew me in 1996 and 1997 would have seen me constantly burning through hand-made Tamil flashcards to boost my working vocabulary. I carried four or five big, rubber-banded stacks in my pant pockets wherever I went. I crammed Tamil vocabulary at the dining hall, in the coffee shop, at the diner up the street, before class started, or whenever I had an hour of downtime and nothing to do. I crammed Tamil as often as you scroll feeds on your phone today.

But once I was in the country, I took the obsession even further. I set a policy of not socializing with Americans, avoiding them like a criminal gang. I knew the temptation to socialize abroad would be too great, including falling into relationships with American college women on year-abroad programs. That would have been a disaster for language acquisition time. In other words, being single and aloof from local Americans was a massive advantage to immersion.

I also deliberately chose to live downtown in a monolingual, working-class neighborhood. This placement ensured that virtually no one would saunter up trying to develop their English with the local white man. If I let myself become a free English Tutor, it would be like finding an American girlfriend. Your brain does not want to dance between languages, even though it can. It would prefer to nestle within one all day.

Every night until 10 p.m., I hung out on the busy downtown street at the end of the alley I lived on. There was a constant throng of passing motorcycles, bikes, cars, and rickshaws to keep you from falling asleep early. A steady stream of pedestrians supplied numerous shops, street vendors, and sidewalk food stalls with customers. People were constantly hanging on the sidewalk and retail stoops—dozens and dozens of them, next to their uncle’s store or their brothers’ shoe stall. All day. Almost all of these folks were monolingual Tamil speakers with at most 10-30 words of English to deploy. They were relieved and overjoyed that I wanted to speak Tamil. Otherwise, they would have never met me.

The one asset a foreigner has learning a local language in India is that so few ever try or pull it off, that you become a truly remarkable human being to them. You have shown them massive amounts of respect they don’t expect from a white person, not in a former British colony.

No one in Europe will give you this much credit (and applause) for becoming fluent in their native language. They couldn’t care less, honestly. When I traveled through Germany during the summer of 1993, I got no love for speaking broken German with anyone, just lots of irritated looks and corrections. Or indifference. I lost motivation.

Reflecting on Gaining Fluency AbroadThis is a ton of work. You may have time as an empty-nester or retired person, sure. But can you handle the identity regression when you speak a new language like a two-year-old? For months on end? Or will you hide out with an English-speaking partner in your downtime and throw away thousands of opportunities to immerse yourself? Do you have the monastic self-discipline to sustain constant immersion when Americans are found everywhere, even in Lesotho?

Unless you are exceptionally gifted at languages, you will need at least a year of waking-hour-immersion to become conversationally fluent in a new language. 3Verbal fluency is very difficult, but it gets harder and harder the more remote the target language is from your native tongue. Consuming media only in the local language will help. This means you have to deliberately not speak English to anyone or spend time on English language newsfeeds. The total immersion is not just for bragging rights. It’s about forcing your brain to think in the new language and stop the process of thinking first in English and then translating to the target language. The latter is NOT fluency. Learning to speak a new language takes massive amounts of repetitive use. And lots of correction early on.

While a year of immersion seems like an incredibly long time, it’s really fast and assumes you are an average or above-average language learner. It takes human children 6-12 years to achieve adult conversational fluency in their native language. Anyone good at languages who arrives with grammar and ~1000 essential words in their head can do usually do this (unless it’s Class III or IV language). Still, a year is a long time to be an awkward, child-like communicator for a grown adult. This regressive quality to language acquisition is much easier to handle emotionally when you’re 16 or 25. Not at 55.

If your intent to resettle abroad is to flee Trumpistan, you are not motivated enough to put yourself through a regressive process of language acquisition that five-year-olds have no choice but to live through. No way.

And no one will trust you if you strap a phone to your face and turn on Google Translate. Sorry. You’re always welcome to try.

Further ReadingIn the past few months, a flurry of really well-done Substack pieces on relocating abroad has emerged, inspired by the dark turn in American politics. Most of these pieces focus on the difficulty of resettling to Europe, the one place most naive Americans assume would be relatively easy. has the most insightful piece to date, well worth reading.

Living ElsewhereAre You One of the Few Americans Who Really Could Move to Europe?If you are considering moving to Europe, I want to offer you ten questions to ask yourself before you decide…Read more4 months ago · 1022 likes · 307 comments · Gregory Garretson

Living ElsewhereAre You One of the Few Americans Who Really Could Move to Europe?If you are considering moving to Europe, I want to offer you ten questions to ask yourself before you decide…Read more4 months ago · 1022 likes · 307 comments · Gregory GarretsonNext week, I’ll explore why moving to Europe could be as challenging, even more difficult, than moving to India. We must dive into subtler cultural dynamics that make resettling or living abroad challenging for Americans.

We have unique cultural handicaps few of us recognize.

NOTE: If you still can not understand how something like Project 2025 gets written and implemented in the Executive branch, you should dive into my new book. A society that privileges lifestyle diversity by making individual autonomy a sacred value will protect both conservative and liberal lifestyles equally. That is how we get to where we are right now. America protects the scientologist, Amish, and atheist, which only leads to greater and greater values incoherence. It is a slow unraveling process.

1

1White men who screwed local Tamil women invited a quick violent response from male relatives and the lifelong guilt of destroying her marriageability within her social class. On the other end, Indian prostitutes were top vectors for AIDs in the 1990s. Exciting options. I was once offered sexual access to a business owner’s niece, but let’s just pretend I did not hear him. Yeah.

278% of Americans age 5 and over speak only English. The bilingual population is less than 22%, since there is a considerable monolingual non-English immigrant population here. Source: US Census, ACS 2023.

3According to the Foreign Service Institute, Tamil is a Class III language for English speakers. It promises a tough slog toward fluency but is not as painful as learning to speak Mandarin or Korean.

March 2, 2025

How We All Got So Rude and Cringe

White Lotus Series 1 Cast - all cringe, all the time

White Lotus Series 1 Cast - all cringe, all the timeHow did we reach a point where incivility, rudeness, and the self-absorption required for each are as likely to come from the old as from the young (who have the excuse of immaturity)?

It’s not reducible to “selfishness.” Selfishness is simply an outcome that restates the problem of weakly connected, low empathy societies (often those recently devastated by invasion, colonialism, or war).

And American civility weakened from within, without a violent civil conflict.

Much of the blame connects to how we think about age and aging.

Let me explain how I got here.

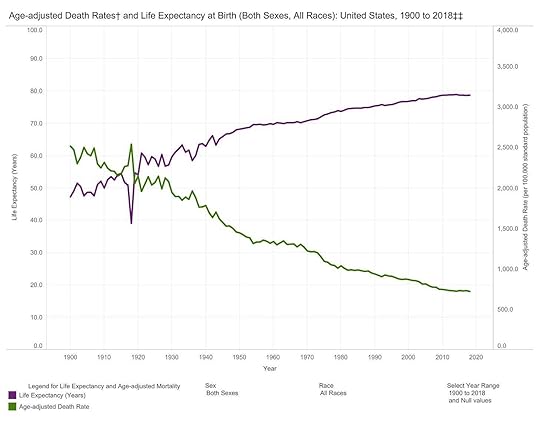

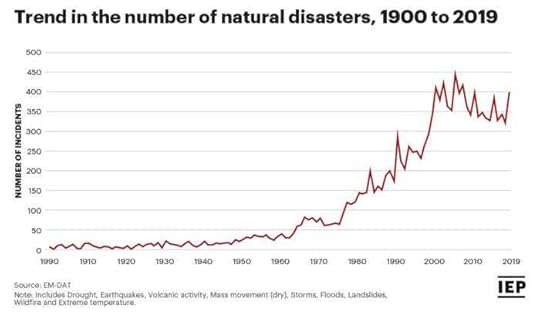

In my 2022 research on older Americans, I learned that age strongly aligns with classic notions of individualism and the primacy of individual agency as the real prize of modern life. ‘The more empowered you are to do whatever you want, the better’ we have been told for generations now (and my grandparents would disagree). The 20th century, in many ways, was the launch of overlapping liberation movements, most of which are still ongoing. We are drunk on personal autonomy.

[Insert grumpy anthropologist].

Growing older has lent men (and many women) maximum relative agency in most human cultures (i.e., relative to their youth). In subsistence-based societies, this was a pure age-based status within resource-sharing clans and had little to do with wealth or income accumulation. However, most human societies also encumbered those elders with more significant obligations as they aged into elder status. One of the most central obligations of the elder has been to enforce social norms and coach naive youth in relatively slow-changing adult behaviors required to contribute to the group. This requires spending time with youth, observing them, and carefully intervening. It required extended copresence. Elders in most societies once lived enmeshed in the lives of youth, not forced to ‘catch up’ twice a year on holidays or less frequently or, in tragic cases, never at all. You must also be trusted as an elder, or no one will listen.

But what if society morphs into a loose association of social network CEOs who are primarily interested in their personal lifestyles rather than social norms?

Then what?

This norm of no-norms has prevailed since the Boomer generation aged into elder status, and it is at the root of most local—and national-level political problems we are dealing with right now. The last generations, who honestly believe in deep intrafamilial obligation, are primarily dead or gone. The usual social variables are not really at play in this shift. It is a naked, societal obsession with lifestyle curation with minimal social obligations. We all love it. Let’s be honest. This truth is so uncomfortable that we refuse to face it, let alone imagine a different way of living together across the ages or simply in broader, tight-knit networks of mutual obligation that we choose.

One reason that older Americans voted for Trump in such large percentages is their obsessive belief in the power of individual autonomy sans the slightest interference from the state. This old demon in America is rooted heavily in the history of our violent frontier and the small farmer’s “off-grid” homestead. Yet, for a long time, even this suspicion of the state did not conquer the bonds of family. Family was too crucial for survival until the mid-20th century. By then, we had rolled out massive federal and state entitlements as safety nets for the poor, weak, and elderly. Now, family was optional as a survival tool.

Once family becomes optional, the elders become optional members of our social lives. And the state becomes more crucial, ironically. The state essentially replaces the old people.

And more than one anthropologist will back me up when I say that once elders are optional, you have hollowed out the entire spinal cord of interpersonal respect in any society. It will only thrive in two forms - the peer-to-peer gang and the bureaucracy. If you can disrespect an elder just for being older and “cheugy,” you have a modern form of social unraveling, not one born from the usual suspects: famine, plague, or war.

America has created an aging process that undermines our most basic forms of relational coherence beyond the romantic couple and the parent/child dyad. As we empty the nest, retire, and experience spousal death, each stage reduces our net total social obligations at the individual level. The primary exception is the aging family business patriarch or matriarch. In its place, older Americans put leisure activities and media consumption (much more than any other age group but teens) ahead of socialization, often unconsciously and with a fair bit of regret. Others love their 55+ rec centers and Netflix.

As I explain in my recent book, modern youth culture has sustained ‘youth contra elder’ age-based social segregation since the 1940s for no reason other than the demands of education-based income growth, labor market evolution, and the consumption both facilitate. Maximizing individual autonomy delinks people from all temporal constraints on personal lifestyle provided by traditional, time-intensive social obligations. It enables lifestyle-based over-consumption (i.e., the engine of GDP growth in modern societies).

As a market researcher who conducted in-depth interviews with hundreds of baby boomers early in my career, I can not easily describe to the non-Boomer how much the average Boomer hates their parents, at least one of them. This hate is not for the usual reasons but because of their parents’ values and value system. And I mean real hatred and disgust, not just annoyance or irritation. This intergenerational parent/child malaise has significantly improved with younger age cohorts because modern parents are better adapted to a world of rapid change (i.e., they know that the rigidity of conservative societies is maladaptive).

Readers may agree or disagree with the long-term societal value in the Boomer rupture of traditional values. Still, their generation set in motion a perpetually reproducing, mass youth culture of norm-rejection that seems normal and progressive to many but has been a crucial muriatic acid on local communities.

This age-based segregation is carved into our lived landscape. It is geographic (or perhaps residential). It has created two Americas - one with less empathy for youth and one with less respect for elder wisdom. As Boomers aged, their individualism simply ran free and wild as they retired, disconnected from any proper understanding of their grandchildren’s world.

A broader age cohort of Gen X and Boomers exhibit high rates of childlessness (i.e., they never raised any children) or only had one child, contributing to relative disinterest in youth issues.1 This only ensures that millions of elders are both disconnected and have little reason to connect with youth.

Some grandparents try harder to understand the reality of today’s youth and do, but no one surveys this tricky, intangible behavior. Grandparents’ physical segregation well beyond a 30-minute drive from their grandkids ( a distance my research has shown is essential to intra-family visitation) makes it implausible that they can meaningfully surveil and intervene in their grandchildren’s lives (and many parents do not want this ‘dated’ advice either).

If you grew up like my maternal grandmother in a large working-class family, lived at home until marriage, then raised a family and took care of your ill spouse, the increasing ‘agency’ or freedom from social obligation you received as a widow may have been enjoyable, even ecstatically so. But she never yearned for this or expected it. Ironically, the Greatest Generation was among the first to experience this bizarre decline in social responsibility as they aged (even though they were raised in a different world).

Now, we consider it a civil right.

The problem that America’s aging process feeds is excessive autonomy. Yet, freedom from social obligation is ultimately a trap. It hands you enormous amounts of leisure time, sure. By itself, this autonomy will not make you happy or happier. We know that functional relationships of mutual obligation make humans happiest.

Decades of living with radical autonomy will also make the inevitable temporary period when you suddenly have to deal with a painful family obligation, like care for a dying parent, all the more strange, stressful, and perceptibly onerous. You may realize that your social responsibility muscle is weak and atrophied (or it never developed, which is my case). You feel guilty that the family obligation annoys you (or you are accidentally callous). And the aging adult with a family obligation intruding on their personal life has far less real help with that family obligation today due to everyone’s precious ‘schedules.’

We are not taught to prioritize this fundamental social fitness because America worships autonomy and agency, not social obligation. The latter is a “drag,” a “cramp in my style,” or whatever today’s teens call it (I looked in slang dictionaries but could not figure this out).

The great challenge of the 21st century in America will be to talk ourselves back into tighter relationships of kin and nonkin that slowly heal us from the adolescent autonomy we’ve turned into an adult way of life.

This is not about returning to the past.

It is not about joining mystical, violent religious movements like the New Apostolic Revolution.

Check out my new book (click the banner below) for more on the 20th-century slow creep of modern individualism as a civil and consumer right. It’s a story-driven, data-rich tour through everyday American life, with many tangents and side branches.

1

1My 2022 national survey discovered that 27% of adults now 50-79 never raised kids at home. n= 2983 adults with a high school degree or older.

February 23, 2025

Exorcising the Academic Curse

Note: This is the final piece in a two-part essay. See Part 1 at this link:

When I received my PhD in February 2002, my perception was that most doctoral students in ANY field wanted to settle down in an academic research position. At least initially. This was the high-status goal for most of us when we started our programs in the 1990s.

As far as I know, no one collects data on doctoral students’ intended careers when they start out. However, federal data on PhD recipients’ immediate plans indicate that the percentage of people who have lined up an immediate academic or postdoc position has shrunk dramatically (from 63% in 2003 to 35% in 2023).1

The universe is NOT rewarding kids like me who naively dreamed of becoming a Professor of Something. And it has not been doing this for some time. It appears that doctoral students are figuring this out earlier in their programs than I did.

Academia’s Abdication of ResponsibilityOver the last thirty years, almost 1/3 of all PhD recipients have no clear commitments upon graduation. The data has slipped magnetically around the 30% mark in the past forty years but does not want to escape it. The percentage is especially high in the fields that the private sector does not desire openly (e.g., the humanities).

How the hell do we let students wind up in this situation in such large percentages? These are not stupid people, needless to say. They are more resourceful than the average Joe, especially if they closed on the degree.

Whether you are floating in this anti-climactic phase after graduation or have decided to leave an academic position that is killing you or a family move forced you to abandon tenure, here is what it feels like to say goodbye -

Instead of heading off to a new post, our family moved back into my parents’ basement. It was an anticlimactic end to my academic career and, frankly, one of the hardest periods of my life. Many professors don’t appreciate how difficult leaving academe can be on their students who expected to be professors. It can be a devastating loss of purpose and identity.2

The psychological devastation hinted at above may seem trivial to anyone who grew up in a working-class home, an inner-city home or an abusive, broken home in any social class. Boo-hoo, some readers will cry sarcastically. Yet, that’s the strange thing about the inner life - our assessment of our social status and psychological safety occurs first inside our minds. And this assessment is entirely relative to our original objectives.

Our misery can persist with no external validation of it—a true curse of the human imagination.

As adults, imagining ourselves in a future state we know nothing about and registering our feelings there isn't easy. Humans are more sophisticated at adaptation than squirrels or mosquitoes, but…we have limits, too.

It is even harder to imagine a happy future state beyond academia when NO ONE TALKS ABOUT leaving academia. When your peers never ‘return’ from beyond the cult to inform you. When the cult abandons you silently, my advisor never followed up after graduation and the final round of recommendation letters she wrote in 2001 (before I jumped out of the castle tower window).

Should I have been surprised? No. And I wasn’t. After all, this person had confessed to me in my early years that “I originally wanted to be a writer, but I have to pay bills!” My advisor wanted to be a novelist but ‘settled’ for tenure in academia, where she ‘advised’ the kid who wanted to be a Professor of Something since he was 16. Richard Russo could have used that conversation in one of his satirical take-downs. I didn’t think it was funny at all, of course.

Academia has always been a vestige of medieval guilds, such as the artisan trades, medicine, law, and architecture. If a Master accepts an Apprentice and the Apprentice does the work, there is a straightforward process with which to advance. The path is laid out. The steps are known. You knew about most of them when you applied to your doctoral program. The goal - tenure - is absolute security in which to do your work.

What you didn’t know, perhaps, is that, unlike a medieval guild, the people in authority today in academia are not committed to everyone’s fate. Their commitment is to drive revenue, supporting their department’s budget and salary. Instead of a protective guild, each step on your journey is a chaotic weeding-out phase with no clear support - and not just during the normal weeding-out phase before being advanced to candidacy.

The first weeding out is no longer structural. It occurs inside the noncommittal relationship between you and your advisor. If this relationship does not spark more or less erotically, however figuratively this transpires, it is very unlikely your advisor will advocate for you like you need them to when it counts.3 You will not become the ‘anointed.’

If you also do not commit to following up on their work, you’ve thrown away the essential tool of flattery. Your advisor formally handed you your dissertation topic in previous eras, and you accepted. The system ensured alignment with the advisor. Smart. By the 1990s, though, America’s culture of lifestyle choice flowed into topic selection, creating the essential permission for advisors to abdicate responsibility for the students they agreed to train. “Hey, that’s not a topic I would pursue” is rarely spoken in a false, noncommittal advisory relationship. Not when everyone could use your tuition dollars.

At the other end of the career ladder in academia, budget cuts and the bizarre circus of ‘cancel culture’ assure PhDs that tenure is no longer permanent.

Academia has become no different than the private sector startup world.

You, the candidate, are the startup. Everything else is negotiable. Everything. You are supporting yourself in a market of oversupplied talent with little obligatory vetting or support from those in authority.

The guild has closed. Capitalism finally broke it.

How to Exorcise The Academic DemonToday, there are more resources for PhDs who need or want to escape the academic clown show, even though they, like me, made this decision at the end of their doctoral journey.

The key to making this work is to embrace being a startup in bodily form. Become that startup hustler you probably once despised as ‘crass’…and…you will ultimately conquer all the petty resentments of doctoral training. Maybe.

As a solopreneur and bestselling business author, I now have more interpersonal, financial, and emotional autonomy than I imagined I would receive with tenure. All I had to give up was an extreme definition of intellectual autonomy. I never enjoyed teaching much, so that was easy to let go of. Looking back, it’s crazy that I fought this change for so long in my head.

“Become the CEO of your life and career” - Our Canadian Friend (see quote above).

Superb advice, but easier said than done for a group of adults who skew highly introverted, suck at networking, and have traditionally gravitated to highly structured settings (i.e. a Guild environment).

There are at least seven kinds of PhD labor. Each has an internal status hierarchy primarily based on the prestige of the host institution. I won’t waste your time mapping that out for you.

The key is that each path demands one or more of the four trade-offs I introduced in Part 1. Some trade-offs are more severe than others.

Trade-Off #1: Intellectual autonomy is inversely correlated to making a lot of money

Trade-Off #2: Collaboration versus working alone.

Trade-Off #3: Intellectual idealism versus highly pragmatic concerns of the real world.

Trade-Off #4: The content of your degree may have very little to do with your new career. You have to become an expert all over again.

I leave it to you to see which of these doctoral clans suffers the ‘worst’ trade-off mix and who benefits the most. I’m too biased. Clearly.

The Intellectuals—This was my original objective and the objective of virtually all doctoral students in the humanities and social sciences. They are the super-opinionated ones who often hate teaching. They engage in vicious intellectual debates for sport and honor. They won’t discuss their ‘work’ with mere plebians. They are obsessed with intellectual purity and have difficulty trading this off in pragmatic work outside the academy. Very rarely, an Intellectual like Jonathan Haidt will write a nonfiction bestseller and morph into the Intellectual’s most highly resented form - the Media Intellectual. They will then quickly trade off many Intellectual friends (e.g., Stephen Jay Gould) and find new ones (desperate to get into the media themselves). These PhDs toil in total obscurity, often with barely grateful students. Even their University Press books rarely sell. Their intellectual labor is for a nanoscopic tribe, frequently highly critical and resentful. Their pay has eroded substantially to the point of outright insult.

The Teachers - This important clan gets paid the worst because they work in non-research positions in nonprofit institutions. Tsk. Tsk. Despite the financial trade-off, the Intellectuals look down on them for obvious reasons - they produce no intellectual output. They transmit the Intellectual’s output to students and savor the feeling of remaining an arbiter of ‘powerful knowledge.’ But the other clans just feel bad for their shitty salaries. If they do not engage in serious hypergamy, their life involves trading off income and prestige in their field. ‘Marry a surgeon or banker’ is my advice. Teachers LOVE their students. Seriously, they do. At my old private high school, these folks even write books to achieve some form of intellectual catharsis. Good for them. We Knowledge Workers pity their salaries but envy their ability to savor the Intellectual goods daily.

The R&D PhDs - These folks work in corporate labs or as mathematical modelers on Wall Street. They are ‘evil sell-outs’ to the Intellectuals, Teachers, and NGO clans. R&D labs are where the reliable money is for PhDs, especially if you can eventually run your own laboratory department funded by a major corporation (or, even better, by rich angel investors). Think of lab scientists in leading-edge labs at Pfizer, 3M, SpaceX, etc. - these PhDs often engage in era-defining research and are paid accordingly. But, there is also an army of corporate R&D PhDs in the less glamorous worlds of consumer goods, industrial manufacturing, and packaging. This work is crucial to the business models and cost containment of companies that make essential goods (e.g., groceries, steel girders, Post-It Notes). These PhDs can also easily point to their ‘work’ in the real world and be proud. Their invisible work becomes visible, unlike the work of the Teachers and Intellectuals. This can be very satisfying, more satisfying than much of the work done by the next clan I want to portray.

The Knowledge Workers - This is where soft social science and humanities folks like me end up. These firms or agencies have ways to use creative and highly analytical brains for all sorts of corporate purposes, from market research to strategy consulting. But they earn a wide salary range. The problem is that an enormous amount of this “work” is what David Graeber describes in his bestseller - Bullshit Jobs. I’ve never seen so much meaningless PowerPoint as I have in the market research sector. When you have to pretend to have a debate with an ad agency twit about human behavior, it’s infuriating and insulting. The Teachers have far more daily fulfillment than these folks and experience less weekly status humiliation. My experience is that the more a Knowledge Worker secretly cares about being an Intellectual, the more they will flounder in rage and the less they will advance and earn in the private sector. Once you can sell knowledge to clients by taking their analytical needs seriously, you can start making good money. Of course, if you are that good and client-focused, you should consider becoming a self-employed consultant. This took me way too long to realize and then execute. Very few of us pull this off. I wrote a book to do it. Not everyone has that opportunity. The worst thing about this clan is that almost all of them do permanently invisible work that leads to nothing in the real world. Maybe a package design on a food product. Maybe. Knowledge Workers make the most trade-offs until they can work for themselves. Because of this, I suspect they are grumpier on average than the Teachers but less so than the poorly paid Intellectuals.

The Startup PhDs - These are the genuinely sexy PhDs, the folks lending their degree halo onto all sorts of entrepreneurial ventures, from on-demand therapy apps to meal replacement nutrition products to SpaceX. They work closely with management and may even be co-founders. If you want a public face and many media opportunities, this is the opposite of the R&D folks toiling in corporate obscurity. I suspect the narcissism index is a wee high among these PhDs. They often make a lot more than the R&D clan, so it tends to be where more experienced, ambitious R&D people go. They are also satisfied with performing visible work worldwide, unlike the Knowledge Workers or Teachers. I’m not sure many feel that they reduced intellectual autonomy because there is a strong alignment between their doctoral work and what they now do. I suspect my elder son may wind up in this clan.

The NGO PhDs - Many of my non-academic anthropologist peers work in international development and foreign aid. They often enter doctoral programs intending to do this. Honestly, it is a more thoughtful approach to your entire program than thinking you’ll be the rare diamond who earns academic tenure. They work in : elite global organizations (e.g., WHO), mega-funded philanthropies (e.g., Bill Gates Foundation), famous NGOs (e.g., World Wildlife Fund, Doctors without Borders), and invisible NGOs (e.g., why would I give you an example?). NGOs perform invisible work mostly abroad, but recipients are grateful for the most part, like recipients of missionary schools and hospitals in prior eras. These folks are not super well paid, but better paid than the Teachers and Intellectuals. I suspect they experience few trade-offs because they are often not interested in Intellectual autonomy or financial glory. I suspect many equally well-paid Knowledge Workers envy the sh*t out these folks.

Government PhDs - This clan gets paid well from the start, better than many Knowledge Workers. But they do have to let go of the desire for intellectual autonomy. Quickly. If they intended to wind up here (and some in Sociology do), then it can be very satisfying and secure work. Government work also leads to more visible public outcomes than the Teachers, Intellectuals and Knowledge Workers experience. These folks can have real authority inside federal agencies where their PhD often confers daily status in the workplace. I can not say the same for the Knowledge Workers or Intellectuals. One other trade-off his clan makes is long-term salary upside. It is entirely dependent on limited promotions. Hence, the most ambitious continue to leave for the private sector (including the NASA to SpaceX parade).

Many career paths involve trade-offs, but the PhD experience is pretty extreme in large part because this degree magnetically attracts a combination of maniacal focus, stubbornness, and intellectual idealism. This is both a weakness when change is necessary (we react slowly) and an enormous superpower when the way to make your PhD work for you long-term is to become the “CEO of your own career.”

PhDs today are used to institutional neglect and indifference, which is precisely what the modern workplace feels like for many. Bring it!

1

1https://ncses.nsf.gov/surveys/earned-...

2https://www.insidehighered.com/advice...#

3Without trying, I collected at least five anecdotes of women fucking their dissertation advisors. I’m willing to bet they all got to tenure-track positions. Needless to say, unless you are a gay male, this approach is unavailable to men (who are rarely attracted to women 10-15 years older).

February 17, 2025

Status Ironies of the Doctoral Degree - Pt. 1

“I have no idea what I’m going to do for a living now,” I said to my temp working peer as we ran simple kinesiological tests for prospective TSA security workers in 2002 at the Grand Hyatt near Chicago O’hare airport.

“Yeah, James, but at least you have a real education,” he replied, referring to my newly minted PhD. Dave was more than a year out of college. The tech stock bubble had burst just as he graduated, so he could not find any meaningful work for a white-collar salary, even at the entry level.

His praise for my PhD was the first signal from the broader public since I had received my degree a few months earlier that a PhD confers some nominal social status. I was not the complete loser I felt after receiving 20+ job rejections in the fall. That experience and other personal factors would soon lead me to leave the tenure-track rat race before it even started.

My un-American philosophy of life was starting to form - when your chosen career track is destroying your mental health and promising no meaningful income, you have to quit early to retain control of your life. You must quit before you are desperate (emotionally or financially). You must quit when your confidence is still strong. This attitude would serve me well again fifteen years later.

But, where was I headed? I had no earthly idea. Anywhere beyond the academy.

Some Doctoral Facts“They seem to give out PhDs like napkins these days,” one of my now-retired former colleagues muttered in contempt of a peer whose mind he did not respect.

Yes, there are a lot of us. 5.6M American adults have a doctoral degree, and about 4.1M have not retired yet.1 One out of a hundred American adults is a working PhD-holder. What? Yes. We’re four times more common than physicians with MD degrees. Only 1.1M doctors are practicing today in the U.S.2 But, don’t worry. The massive pile of PhDs is not due to an outbreak of English literature disease or a pandemic of concern with medieval Anglo-Saxon literature. Not at all.

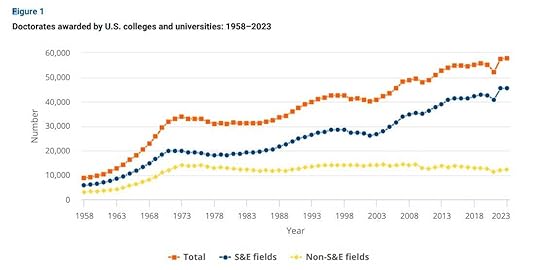

2023 U.S. Survey of Earned Doctorates - The National Science Foundation

2023 U.S. Survey of Earned Doctorates - The National Science FoundationAmerica has grown its annual production of PhDs sixfold in the past sixty years - from 9,000 in 1958 to 59,000 in 2023. That’s a visually significant increase in this chart, but, more importantly, this annual production grew three times faster than population growth during the same period (i.e., from 174M to 334M). And 90% of this increase in annual PhD granting has been in science and engineering, not my sad, low-status world of the humanities and social sciences.

As PhDs graduate, the humanities and social sciences continue to have the worst immediate employment records.

2023 Survey of Earned Doctorates - The National Science Foundation

2023 Survey of Earned Doctorates - The National Science FoundationWhen 35% of newly minted Ph.D.s in a field can not find jobs (presumably worthy of the degree), we are either overproducing them or not preparing them intelligently for employment. Universities are abdicating their responsibility to throttle admissions and set up applied tracks in return for lazily harvesting tuition income. I can assure you that MBA programs would get shut down if their immediate employment record was this bad. They shoot for 99%.

But the story gets weirder for those who chose PhDs in low-status, chronically under-employed fields.

The percentage of all PhDs going straight into private sector industry jobs is now 50%, more than twice what it was in 2003, roughly when I graduated. And the chronically under-employed social science fields are still the lowest producer of PhDs headed into the capitalist beast. Most of “us” work in government, NGOs or teach. The lack of movement from school into the private sector is not structural. It’s not a resume problem. I can tell you from direct immersion that a PhD recipient not going into the private sector originates in the personal hang-ups of the PhD holder. They simply can not escape the ‘cult.’ Luckily for me, I was never fully ‘captured.’

As humanities and social science PhDs continue to be overproduced and avoid private sector work, the PhD has slowly become a lucrative, mostly corporation-inspired degree, heavily weighted toward the hard sciences.

The dominance of ‘intellectuals’ in any field of doctoral study is long gone.

The Financial Prize of a PhDThe most basic and all-American definition of social status is annual personal income. If you’ve ever gone through a considerable income loss (even due to a career switch you otherwise wanted), you know how much that income loss can haunt you mentally. When my wife saw her first paycheck as a high school nurse, after being a highly paid customer success executive, she described it correctly as “insulting.”

Highly educated Americans tend to be salary-strokers because it’s costly to live here and because chasing higher salaries means we can consume more. Consumption, not work, is our national religion and our most sacred obligation. We may mask our consumption with lifestyle activities of a higher purpose (e.g., trail running and $300 trail-running shoes), but it’s still there. So, aligning our identities firmly with our salary is part of life here.

Coming from the lowest-earning segment of PhDs (those with humanities and soft social science degrees), I can attest to thousands of my peers who earn little in academia, journalism, and high school/college teaching. Some are pretty happy. Most I suspect are not as happy as they claim at Thanksgiving. Not really. They swallow their failed intellectual dreams every night when they go to sleep. And they’re tired of the bitter kale taste of their low salaries. Not caring about money has a certain status glow when you’re in your 20s. By 40, you just look sad. Here’s an extreme example to ponder - A Ph.D.-holding physics professor who is now homeless because his department won’t provide a living wage for a single adult in the local area.

@209timescaUCLA Physics Professor Says He’s Homeless Due to Low Pay In a viral video with over a million views on TikTok, UCLA professor, Dr. Daniel McKeown, says only being paid $70,000 a year by the state of California has left him homeless. His video is made outside of a storage unit he put all of his belongings in because he says he lost his apartment in Westwood and now is staying at a friend’s hours away. As a result he has to teach virtually online. He says he asked for a raise to $100,000 a year so he could afford his rent, but was denied by the university. He also calls out the administration and asks others to protest with him stating that, “tuition is being stolen” because it’s going to administration and not professors. Both the CSU and UC systems have continued to raise “fees” in a system that was designed to be tuition free for California students. The Newsom administration has done nothing to curb the rate hikes that are part of the California government. McKeown says in a separate video that his rent was $2,500 a month. According to online real estate sources, the average rent in Westwood is $3,700.. The average cost to attend UCLA is $34,667 for in-state students with the cost of tuition and fees alone costing $13,225. This is a problem not only happening at UCLA, but statewide at other universities in the CSU/UC system from Chico and Sac State in Northern California to UC Merced and Stanislaus State in the Central Valley. The rent and tuition is too damn high and the pay is too damn low! #losangeles #LA #sacramento #merced #chico #sacstate #ucla #csula #stanislausstate[image error]Tiktok failed to load.

@209timescaUCLA Physics Professor Says He’s Homeless Due to Low Pay In a viral video with over a million views on TikTok, UCLA professor, Dr. Daniel McKeown, says only being paid $70,000 a year by the state of California has left him homeless. His video is made outside of a storage unit he put all of his belongings in because he says he lost his apartment in Westwood and now is staying at a friend’s hours away. As a result he has to teach virtually online. He says he asked for a raise to $100,000 a year so he could afford his rent, but was denied by the university. He also calls out the administration and asks others to protest with him stating that, “tuition is being stolen” because it’s going to administration and not professors. Both the CSU and UC systems have continued to raise “fees” in a system that was designed to be tuition free for California students. The Newsom administration has done nothing to curb the rate hikes that are part of the California government. McKeown says in a separate video that his rent was $2,500 a month. According to online real estate sources, the average rent in Westwood is $3,700.. The average cost to attend UCLA is $34,667 for in-state students with the cost of tuition and fees alone costing $13,225. This is a problem not only happening at UCLA, but statewide at other universities in the CSU/UC system from Chico and Sac State in Northern California to UC Merced and Stanislaus State in the Central Valley. The rent and tuition is too damn high and the pay is too damn low! #losangeles #LA #sacramento #merced #chico #sacstate #ucla #csula #stanislausstate[image error]Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

He looks like and sounds like Steve Jobs. And, I presume, only a tenured (or insane) professor could openly attack his boss by name on the internet. That Monday faculty meeting must be fun.

Like him, many doctoral students do not originally care much about money. Many have intellectually intense research desires. I was the same way. Yet, in aggregate, PhDs correlate with very high incomes typical of most post-grad educated adults. And at 52, after many twists and turns, I am a perfect example of this.

My Dad clung to this hope without any data supporting it as he floated my rent in 2002. It turns out that he was mostly correct in his optimism.

Here’s what the 2024 annual CPS survey from the US Census reveals about the financial power of the average PhD:

IPUMS CPS database of 2024 CPS data collected every March; this chart covers 185M working, underemployed, and unemployed adults; retirees were filtered out to tighten the accuracy

IPUMS CPS database of 2024 CPS data collected every March; this chart covers 185M working, underemployed, and unemployed adults; retirees were filtered out to tighten the accuracyThe chart above anchors the earning power of a PhD in a broad national context, including high school dropouts. The bars are not equal income jumps. They are multiples of U.S. personal median income (i.e. $45,000) to expose the pattern better. Green = those who earn at or below the median personal income (i.e., 50% of Americans earn below $45,000).

Here’s what it shows:

85% of PhD holders earn more than the median personal income.

65% earn more than twice the median.

30% earn more than four times the median!

By the time PhD holders hit their 50s, 36% earn more than four times the median income.

The PhD, in general, pays off…eventually…quite well. On average, it’s as good as a professional degree in boosting your income. But not for everyone. In a loosely regulated labor and higher education marketplace, America is more than happy to let a minority fall right through the cracks and shrug out shoulders. The reality of an early-twentieth-century PhD holder, almost certainly an academic with secretaries, staff, and an excellent salary, is long gone. That clarity of elite social status is just no longer true for all of those who slog through a doctoral program.

Around 5,000,000 adults with only a high school degree earn more than 2X the median personal income - more than 1.3M PhD holders (including tenured professors)!

35,000,000 college graduates with no advanced degree make more than 2X the median personal income, crushing the incomes of 15% of PhD holders. Yes, these people sometimes bump into each other (often at kids’ soccer games!)

A master’s degree is almost as effective in raising your earnings as a PhD, mostly because MBAs dominate this group.

The percentage of PhDs earning low incomes (the green bars) only drops from 14% to 10% as we shift from younger to older PhD workers. 11% of PhDs in their 50s are still under-earning their peers and have been for quite some time.

I could have been one of the latter ironies. I came pretty close. And it was more than an issue of a low-status anthropology PhD. Let me explain.

When I started in corporate market research in 2003, I earned $45,000 or $78,000 in today’s dollars. That put me above the median personal income at the age of thirty-one. At the same time, I had college roommates earning twice as much. But, I had escaped the nightmare of touring rural America to grab visiting college teaching positions that paid around $20,000.

Joining the market research sector doubled my earnings immediately.

But get this. When I was interviewing for the market research job I eventually took, I was also three days away from flying to DC to interview for a Leadership Analyst job at the Directorate of Intelligence inside the CIA. Because the federal government has automatic base pay based on your educational attainment, even for an entry-level worker, a newly hired PhD traditionally confers immediate GS-11 status. I remember using federal websites to calculate my Virginia-based GS-11 minimum salary at around $90,000 in 2003.

So, in the span of a few weeks in February of 2003, I scanned jobs offering $20K, $45K, and $90K for the same PhD in Cultural Anthropology! Um, that’s a lot of variance, folks. From ‘ineligible bachelor’ to ‘attractive chap.’ At least, that’s how my lonely brain processed these numbers at the time. How can nine years of work, including three of mildly dangerous fieldwork, yield so much differing value? This variance then puts an enormous responsibility on one’s shoulders. And it also invokes a complicated set of trade-offs outsiders have a hard time understanding.

Almost 1,000,000 PhD holders today earn less than the median personal income for all that hard work, with all that debt. In 2003, I was hellbent on NOT being one of these people.

But how do I select a career I know nothing about and within which I know absolutely no one at all?

I remember thinking, “It's crazy that I’m making this decision almost entirely by myself with so little information.”

The Awkard Trade-Offs In PhD Employment No One DiscussesTrade-Off #1: Intellectual autonomy is inversely correlated to making a lot of money with your PhD. Not until you are elite enough in your field to set up your own institution (most never get this chance). If you did not intend to work outside the academy, this is a big psychological issue you must overcome. To regain intellectual autonomy, you must become an expert a second time in your new industry. After 5-9 years of slog, this is very bitter, raw kale to chew.

Trade-Off #2: Collaborating in tightly managed work teams will also pay better (e.g. corporate labs or consulting firms), though you, the PhD, may prefer working alone. Again, this is very true for those in the humanities and social sciences (a refuge for many a bright introvert).

Trade-Off #3: Intellectual idealism runs into highly pragmatic bureaucratic concerns of the real world…and very quickly. For example, being asked to do specious, low-quality research due to a client’s temporal expediency and political nervosity is not uncommon in market research.

Trade-Off #4: The content of your degree may have very little to do with your new career. This is most true for humanities and social sciences PhDs. The PhD has become mainly a labor market symbol of a rare combination of traits: high intelligence + strong work ethic + advanced critical and imaginative thinking. Translation: we’re superb, intrinsically motivated individual contributors in an ocean of externally motivated, average-IQ worker drones. I used to think this last bit was just snobbery until I entered the American workforce. Oh. My. God. No wonder I got promoted five times. And I always hired people with strong work ethics as well. That honestly matters more than raw intelligence to anyone managing a team.

Like most Americans, PhD holders view their degree’s status power based on how the following variables play out: how much income they receive, the prestige of their institution in their social world, the deference they receive at work, and the general prestige they have in public.

Most PhDs do not earn 1% incomes, work at high-prestige institutions (e.g., Yale), have elite media brands (e.g., Jonathan Haidt), or have high status in their workplace; virtually none have all four. When I was at Harvard in the early 1990s, the late Stephen Gould’s colleagues did not consider him a serious biologist. He was a media sell-out to them. His books are excellent. Gould provided an outstanding public service during the back half of his career by making evolutionary biology exciting and accessible to everyday readers. No one remembers his jealous, snide colleagues. Status incongruity even for the “celebrity professor.”