The Evolution of Tragedy - From Premature Deaths to Urban Disasters?

Lahaina, Maui, Hawaii, Aug. 8-16, 2023

Lahaina, Maui, Hawaii, Aug. 8-16, 2023High infant mortality and maternal mortality before modern prenatal and postnatal medicine. Smallpox, measles, polio, influenza, food poisoning, and tuberculosis before vaccines and antibiotics. Child malnutrition. Farm accidents. Death from heart attacks, strokes, and injury blood loss before 911 services. Rampant organized crime in urban centers. Cancer that was undetected and largely untreated. Severe mental illness that led to incarceration and unexplained holes in family trees.

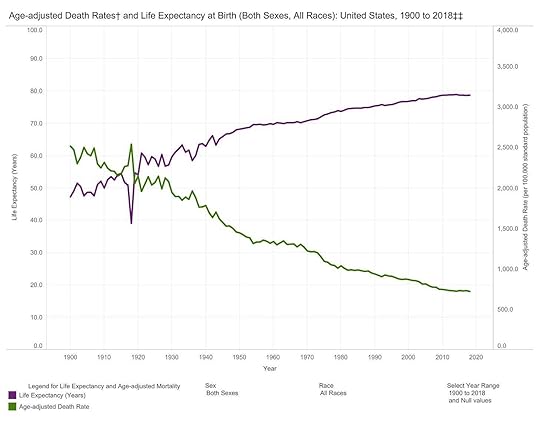

Before WWI, this was the reality in one of the world's top three wealthiest nations (GDP per capita). America was wealthy but infused with a steady flow of tragedy in most people’s social networks. The U.S. mortality rate was 3.3 times higher in 1900 than today. The chart below shows the long-term decline in age-adjusted mortality (the rate of annual deaths per 1,000 people) caused by advances in infectious disease containment through World War II.

On the left, you can see how the early waves of the Spanish Flu created a massive mortality spike in 1918, long before intensive and advanced respiratory care became available at most local hospitals.

This was the world in which my maternal grandparents came of age—a world of frequent premature death in family networks. My grandmother lost a sister to the Spanish flu. Her husband lost his first wife to an infectious disease and became a single Dad for several years in the 1930s. These tales are familiar to every family from this era if you were lucky enough to gather them up decades ago.1 Not only were deaths in 1900 disproportionately caused by infectious disease (the top three leading causes), but 40% of these infectious deaths were children under the age of five.2

The key social fact I’m pointing to is the much higher frequency of premature deaths in this era: the deaths of children and working-age adults needed by their families. An 85-year-old dying of old age is not really “tragic” for most of us. It’s sad, yet expected. But, in 1900, your average social network had both children and the elderly dying at much higher rates than today due to the specter of infectious disease.

When you consider that Americans tended to have tighter family networks and people living nearby during this era, it almost guaranteed encounters with tragedy (i.e. premature death) multiple times a year. In 2023, YouGov determined that only 37% of American adults had been to a funeral in the past year. Suppose that number includes people who went to just one funeral and that it was most likely not for a tragic premature death but simply for grandma. If true, death itself, let alone premature death, is unlikely to be a frequent reality for most Americans (who live outside of our most violent neighborhoods).

Death once spanned the entire age continuum. And you never joked about it, let alone the death of someone you knew. This ancient human rule still exists in poor communities worldwide, such as in rural India and Africa. It’s just not funny when a home’s primary earner suddenly disappears. Or when a future earner, a 2-year-old, dies of cholera. In the world circa 1900, social networks received routine, devastating wounds that families had to overcome.

Most importantly, premature death (as an ancient form of tragedy) makes local community bonds more critical. When I say ‘community,’ I’m referring to family and neighborhood-based resources - labor and cash - that allow grieving survivors to recover by covering for lost wages and offering domestic labor as individuals recover emotionally. If your family was broken or had alienated too many locals (i.e., through alcoholism or criminality), however, the premature death of a father often led to tragic dissolution and children winding up in state orphanages and child asylums.3

Here’s the thing. Even though premature death (and death overall) was more everpresent in the pre-WWII era, individuals still had to have a strong emotional bond with that individual for it to register as a tragedy (versus more sad news on CNN). A tragic, premature death that hurts is tricky to operationalize for a survey because defining an ‘intense emotional bond’ is very squirrelly. We might say that we experience tragic death in proportion to the social intimacy we have with the prematurely dead. These are the people we spend the most time with every week (minus those we hate at work), the people with whom we were socially intimate earlier in our lives, influential mentors and leaders from any point in our lives, and VIPs in our social network that we know.

The Banishment of Death From Everyday LifeNot only has America witnessed a massive drop in premature death from infectious diseases, but we have also banished death itself to the statistical margins of everyday life. For many, death is something we primarily experience as we age and our social network starts dying. In other words, the first 50-60 years or so can be shockingly death-free, especially premature death.

While very challenging to measure precisely (i.e., per capital funeral attendance trends do not exist), we can infer a decline in experiencing death in everyday life based on a few facts we do know -

significant decline in mortality per capita (death is simply less widespread)

decline in family intimacy (we most likely have strong emotional attachments to fewer family members than in prior eras)

decline in the average adult’s close friends in the last quarter century is pronounced

I am 52 years old, and I have been to just one funeral - for my maternal grandfather. I’ve experienced just one premature death in my social network of friends and family. Just one tragic death in the universe of individuals I have spent a lot of time with in my life. That individual was a tenure-track professor of anthropology who once taught me Tamil at the University of Chicago. Just one premature death of someone I knew closely.

Death has mainly become a phenomenon experienced by older Americans due to poor lifestyle choices and causes related to age itself. Why is this? One primary reason is the intensification of modern youth culture that separates youth from their elders and weakens their relationships with those most likely to die within their social network in any given year. Younger Americans live in a social network of middle-aged to younger folks, with sporadic contact with elders. Young people may go to the funeral of grandparents and perhaps their siblings…maybe. But, generally, they do not know their parents’ friends or have distant relations with their grandparents or parents.

In our society, not unlike Japan, we have physically segregated elders into apartments, 55+ communities, retirement homes, and nursing homes; the elders’ deaths are also far less visible in public spaces due to funerary laws that control the processing of the dead. In India, the dead are still processed right through the streets as a form of public announcement on the family’s way to equally visible and public cremation sites. There is no habit of using hearses where the identity of the dead is double-sealed from view. You may or may not ‘know’ the deceased passing by you on the shoulders of their relatives. Still, Indian funerary processions cause you to ask and inquire, further cementing community self-understanding.

Hindu Funeral Procession - Nimtala Ghat Street - Kolkata 2016-10-11. Wiki-Commons.

Hindu Funeral Procession - Nimtala Ghat Street - Kolkata 2016-10-11. Wiki-Commons.In modern America, not only is death less part of ordinary life, less likely than ever to be considered ‘premature,’ it is also primarily invisible and heavily concealed from the public.

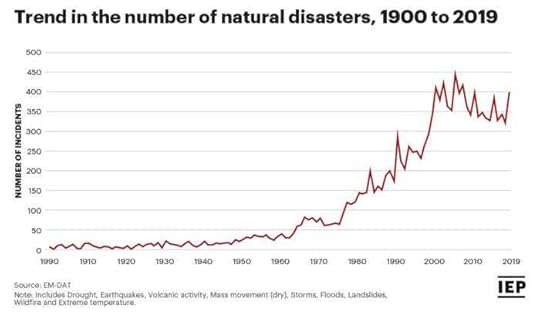

Have ‘Natural’ Disasters Replaced Premature Deaths?Our ancestors once used the phrase “Acts of God” to describe natural disasters. You’ll still see this old colloquial phrase in legal contracts (where many archaic vernacular language lives on). Solid evidence shows that global natural disasters increased rapidly in the late 20th century and occur at a sustained high-level today (mostly floods and hurricanes).4 And the impact on the built environment in terms of financial damages has been increasing steadily here in the U.S. when we look at inflation-adjusted data.5

Interestingly, the death toll from natural disasters has been going down in the U.S. due to increased public planning, media alerts, and a public that is financially capable of evacuating with a minimal heads up (1-2 days).6

The tragedy posed by natural disasters is less the death toll and primarily the destruction of our built environment. In a highly materialistic society like the United States, losing your home and its possessions is arguably a more devastating hit than it would have been to my grandparents in 1900. They owned little, and rebuilding a small, simple wooden house back then - a home with almost no modern amenities- was vastly cheaper.

In today’s urban world, we face increased risks of floods, storms, and wildfires taking away our physical home (and sanctuary) and neighborhoods. These rising Acts of God do not discriminate by social class any more than infectious disease did in 1900. They may strike the Pacific Palisades OR Altadena.

The jarring reaction of Palisades residents is understandable. These fires overtook neighborhoods in a matter of minutes. While most appear to have escaped, the tragedy occurred in the built environment. Very wealthy people lost everything, along with their middle-class neighbors. The wealthy Palisades elite also had more valuable ‘stuff’ to lose. Given how much more we fetishize our homes than our less materialistic, more family-oriented ancestors, the emotional intensity of natural disasters as tragedies has a very modern ring.

The experience of natural disasters today may become one of the most tremendous external forces (outside of war) that could bring communities back together and make them more cohesive than our 20th-century affluence could accomplish.

But will we come together and rebuild more physically resilient communities? Or will many just flee the state while the 1% quickly pay to rebuild fire-proof concrete mega-bunkers?

I am not sure.

After all, the known preventative urban wildfire prevention measures involve tactics that most homeowners are unlikely to observe—clearing plants and vegetation from a large radius around their house and spending tens of thousands to re-design their siding and rooflines.7 Setting the proper radius often runs up against your neighbor’s home, making population density in single-family home neighborhoods a considerable part of the problem in rebuilding resilient communities in a disaster-prone America.

Our individualistic fetish for separate, personally landscaped oases versus living in large concrete and steel congregate dwellings is staring right at us. Today's flood, storm, and fire damage points awkwardly to our obsession with high-density single-family home neighborhoods and our individualistic entitlement to ‘do whatever I want with my property.’

If we could overcome some 20th-century entitlements, such as extreme individualism, there could be a fantastic urban dwelling revolution in the next quarter century. One that hardens us against a rising occurrence of super-destructive natural disasters stoked in part by ongoing climate change.

1

1To be fair, there is simply no statistically valid measurement of the frequency of death in adult social networks, let alone one in the past to which we could compare. So, I’ll be using basic inference to make my point.

2https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwr...

3The era of elaborate individual entitlements (i.e., unemployment insurance, WIC, Medicaid) had not developed.

4https://www.visionofhumanity.org/what...

5https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/bill...

6https://www.visualcapitalist.com/cp/i...

7