Status Ironies of the Doctoral Degree - Pt. 1

“I have no idea what I’m going to do for a living now,” I said to my temp working peer as we ran simple kinesiological tests for prospective TSA security workers in 2002 at the Grand Hyatt near Chicago O’hare airport.

“Yeah, James, but at least you have a real education,” he replied, referring to my newly minted PhD. Dave was more than a year out of college. The tech stock bubble had burst just as he graduated, so he could not find any meaningful work for a white-collar salary, even at the entry level.

His praise for my PhD was the first signal from the broader public since I had received my degree a few months earlier that a PhD confers some nominal social status. I was not the complete loser I felt after receiving 20+ job rejections in the fall. That experience and other personal factors would soon lead me to leave the tenure-track rat race before it even started.

My un-American philosophy of life was starting to form - when your chosen career track is destroying your mental health and promising no meaningful income, you have to quit early to retain control of your life. You must quit before you are desperate (emotionally or financially). You must quit when your confidence is still strong. This attitude would serve me well again fifteen years later.

But, where was I headed? I had no earthly idea. Anywhere beyond the academy.

Some Doctoral Facts“They seem to give out PhDs like napkins these days,” one of my now-retired former colleagues muttered in contempt of a peer whose mind he did not respect.

Yes, there are a lot of us. 5.6M American adults have a doctoral degree, and about 4.1M have not retired yet.1 One out of a hundred American adults is a working PhD-holder. What? Yes. We’re four times more common than physicians with MD degrees. Only 1.1M doctors are practicing today in the U.S.2 But, don’t worry. The massive pile of PhDs is not due to an outbreak of English literature disease or a pandemic of concern with medieval Anglo-Saxon literature. Not at all.

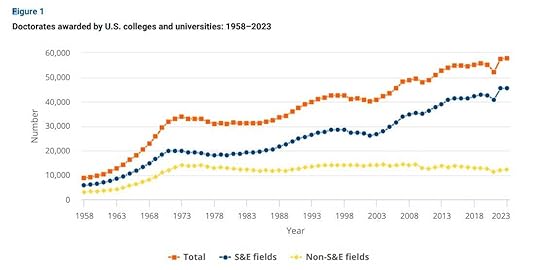

2023 U.S. Survey of Earned Doctorates - The National Science Foundation

2023 U.S. Survey of Earned Doctorates - The National Science FoundationAmerica has grown its annual production of PhDs sixfold in the past sixty years - from 9,000 in 1958 to 59,000 in 2023. That’s a visually significant increase in this chart, but, more importantly, this annual production grew three times faster than population growth during the same period (i.e., from 174M to 334M). And 90% of this increase in annual PhD granting has been in science and engineering, not my sad, low-status world of the humanities and social sciences.

As PhDs graduate, the humanities and social sciences continue to have the worst immediate employment records.

2023 Survey of Earned Doctorates - The National Science Foundation

2023 Survey of Earned Doctorates - The National Science FoundationWhen 35% of newly minted Ph.D.s in a field can not find jobs (presumably worthy of the degree), we are either overproducing them or not preparing them intelligently for employment. Universities are abdicating their responsibility to throttle admissions and set up applied tracks in return for lazily harvesting tuition income. I can assure you that MBA programs would get shut down if their immediate employment record was this bad. They shoot for 99%.

But the story gets weirder for those who chose PhDs in low-status, chronically under-employed fields.

The percentage of all PhDs going straight into private sector industry jobs is now 50%, more than twice what it was in 2003, roughly when I graduated. And the chronically under-employed social science fields are still the lowest producer of PhDs headed into the capitalist beast. Most of “us” work in government, NGOs or teach. The lack of movement from school into the private sector is not structural. It’s not a resume problem. I can tell you from direct immersion that a PhD recipient not going into the private sector originates in the personal hang-ups of the PhD holder. They simply can not escape the ‘cult.’ Luckily for me, I was never fully ‘captured.’

As humanities and social science PhDs continue to be overproduced and avoid private sector work, the PhD has slowly become a lucrative, mostly corporation-inspired degree, heavily weighted toward the hard sciences.

The dominance of ‘intellectuals’ in any field of doctoral study is long gone.

The Financial Prize of a PhDThe most basic and all-American definition of social status is annual personal income. If you’ve ever gone through a considerable income loss (even due to a career switch you otherwise wanted), you know how much that income loss can haunt you mentally. When my wife saw her first paycheck as a high school nurse, after being a highly paid customer success executive, she described it correctly as “insulting.”

Highly educated Americans tend to be salary-strokers because it’s costly to live here and because chasing higher salaries means we can consume more. Consumption, not work, is our national religion and our most sacred obligation. We may mask our consumption with lifestyle activities of a higher purpose (e.g., trail running and $300 trail-running shoes), but it’s still there. So, aligning our identities firmly with our salary is part of life here.

Coming from the lowest-earning segment of PhDs (those with humanities and soft social science degrees), I can attest to thousands of my peers who earn little in academia, journalism, and high school/college teaching. Some are pretty happy. Most I suspect are not as happy as they claim at Thanksgiving. Not really. They swallow their failed intellectual dreams every night when they go to sleep. And they’re tired of the bitter kale taste of their low salaries. Not caring about money has a certain status glow when you’re in your 20s. By 40, you just look sad. Here’s an extreme example to ponder - A Ph.D.-holding physics professor who is now homeless because his department won’t provide a living wage for a single adult in the local area.

@209timescaUCLA Physics Professor Says He’s Homeless Due to Low Pay In a viral video with over a million views on TikTok, UCLA professor, Dr. Daniel McKeown, says only being paid $70,000 a year by the state of California has left him homeless. His video is made outside of a storage unit he put all of his belongings in because he says he lost his apartment in Westwood and now is staying at a friend’s hours away. As a result he has to teach virtually online. He says he asked for a raise to $100,000 a year so he could afford his rent, but was denied by the university. He also calls out the administration and asks others to protest with him stating that, “tuition is being stolen” because it’s going to administration and not professors. Both the CSU and UC systems have continued to raise “fees” in a system that was designed to be tuition free for California students. The Newsom administration has done nothing to curb the rate hikes that are part of the California government. McKeown says in a separate video that his rent was $2,500 a month. According to online real estate sources, the average rent in Westwood is $3,700.. The average cost to attend UCLA is $34,667 for in-state students with the cost of tuition and fees alone costing $13,225. This is a problem not only happening at UCLA, but statewide at other universities in the CSU/UC system from Chico and Sac State in Northern California to UC Merced and Stanislaus State in the Central Valley. The rent and tuition is too damn high and the pay is too damn low! #losangeles #LA #sacramento #merced #chico #sacstate #ucla #csula #stanislausstate[image error]Tiktok failed to load.

@209timescaUCLA Physics Professor Says He’s Homeless Due to Low Pay In a viral video with over a million views on TikTok, UCLA professor, Dr. Daniel McKeown, says only being paid $70,000 a year by the state of California has left him homeless. His video is made outside of a storage unit he put all of his belongings in because he says he lost his apartment in Westwood and now is staying at a friend’s hours away. As a result he has to teach virtually online. He says he asked for a raise to $100,000 a year so he could afford his rent, but was denied by the university. He also calls out the administration and asks others to protest with him stating that, “tuition is being stolen” because it’s going to administration and not professors. Both the CSU and UC systems have continued to raise “fees” in a system that was designed to be tuition free for California students. The Newsom administration has done nothing to curb the rate hikes that are part of the California government. McKeown says in a separate video that his rent was $2,500 a month. According to online real estate sources, the average rent in Westwood is $3,700.. The average cost to attend UCLA is $34,667 for in-state students with the cost of tuition and fees alone costing $13,225. This is a problem not only happening at UCLA, but statewide at other universities in the CSU/UC system from Chico and Sac State in Northern California to UC Merced and Stanislaus State in the Central Valley. The rent and tuition is too damn high and the pay is too damn low! #losangeles #LA #sacramento #merced #chico #sacstate #ucla #csula #stanislausstate[image error]Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

He looks like and sounds like Steve Jobs. And, I presume, only a tenured (or insane) professor could openly attack his boss by name on the internet. That Monday faculty meeting must be fun.

Like him, many doctoral students do not originally care much about money. Many have intellectually intense research desires. I was the same way. Yet, in aggregate, PhDs correlate with very high incomes typical of most post-grad educated adults. And at 52, after many twists and turns, I am a perfect example of this.

My Dad clung to this hope without any data supporting it as he floated my rent in 2002. It turns out that he was mostly correct in his optimism.

Here’s what the 2024 annual CPS survey from the US Census reveals about the financial power of the average PhD:

IPUMS CPS database of 2024 CPS data collected every March; this chart covers 185M working, underemployed, and unemployed adults; retirees were filtered out to tighten the accuracy

IPUMS CPS database of 2024 CPS data collected every March; this chart covers 185M working, underemployed, and unemployed adults; retirees were filtered out to tighten the accuracyThe chart above anchors the earning power of a PhD in a broad national context, including high school dropouts. The bars are not equal income jumps. They are multiples of U.S. personal median income (i.e. $45,000) to expose the pattern better. Green = those who earn at or below the median personal income (i.e., 50% of Americans earn below $45,000).

Here’s what it shows:

85% of PhD holders earn more than the median personal income.

65% earn more than twice the median.

30% earn more than four times the median!

By the time PhD holders hit their 50s, 36% earn more than four times the median income.

The PhD, in general, pays off…eventually…quite well. On average, it’s as good as a professional degree in boosting your income. But not for everyone. In a loosely regulated labor and higher education marketplace, America is more than happy to let a minority fall right through the cracks and shrug out shoulders. The reality of an early-twentieth-century PhD holder, almost certainly an academic with secretaries, staff, and an excellent salary, is long gone. That clarity of elite social status is just no longer true for all of those who slog through a doctoral program.

Around 5,000,000 adults with only a high school degree earn more than 2X the median personal income - more than 1.3M PhD holders (including tenured professors)!

35,000,000 college graduates with no advanced degree make more than 2X the median personal income, crushing the incomes of 15% of PhD holders. Yes, these people sometimes bump into each other (often at kids’ soccer games!)

A master’s degree is almost as effective in raising your earnings as a PhD, mostly because MBAs dominate this group.

The percentage of PhDs earning low incomes (the green bars) only drops from 14% to 10% as we shift from younger to older PhD workers. 11% of PhDs in their 50s are still under-earning their peers and have been for quite some time.

I could have been one of the latter ironies. I came pretty close. And it was more than an issue of a low-status anthropology PhD. Let me explain.

When I started in corporate market research in 2003, I earned $45,000 or $78,000 in today’s dollars. That put me above the median personal income at the age of thirty-one. At the same time, I had college roommates earning twice as much. But, I had escaped the nightmare of touring rural America to grab visiting college teaching positions that paid around $20,000.

Joining the market research sector doubled my earnings immediately.

But get this. When I was interviewing for the market research job I eventually took, I was also three days away from flying to DC to interview for a Leadership Analyst job at the Directorate of Intelligence inside the CIA. Because the federal government has automatic base pay based on your educational attainment, even for an entry-level worker, a newly hired PhD traditionally confers immediate GS-11 status. I remember using federal websites to calculate my Virginia-based GS-11 minimum salary at around $90,000 in 2003.

So, in the span of a few weeks in February of 2003, I scanned jobs offering $20K, $45K, and $90K for the same PhD in Cultural Anthropology! Um, that’s a lot of variance, folks. From ‘ineligible bachelor’ to ‘attractive chap.’ At least, that’s how my lonely brain processed these numbers at the time. How can nine years of work, including three of mildly dangerous fieldwork, yield so much differing value? This variance then puts an enormous responsibility on one’s shoulders. And it also invokes a complicated set of trade-offs outsiders have a hard time understanding.

Almost 1,000,000 PhD holders today earn less than the median personal income for all that hard work, with all that debt. In 2003, I was hellbent on NOT being one of these people.

But how do I select a career I know nothing about and within which I know absolutely no one at all?

I remember thinking, “It's crazy that I’m making this decision almost entirely by myself with so little information.”

The Awkard Trade-Offs In PhD Employment No One DiscussesTrade-Off #1: Intellectual autonomy is inversely correlated to making a lot of money with your PhD. Not until you are elite enough in your field to set up your own institution (most never get this chance). If you did not intend to work outside the academy, this is a big psychological issue you must overcome. To regain intellectual autonomy, you must become an expert a second time in your new industry. After 5-9 years of slog, this is very bitter, raw kale to chew.

Trade-Off #2: Collaborating in tightly managed work teams will also pay better (e.g. corporate labs or consulting firms), though you, the PhD, may prefer working alone. Again, this is very true for those in the humanities and social sciences (a refuge for many a bright introvert).

Trade-Off #3: Intellectual idealism runs into highly pragmatic bureaucratic concerns of the real world…and very quickly. For example, being asked to do specious, low-quality research due to a client’s temporal expediency and political nervosity is not uncommon in market research.

Trade-Off #4: The content of your degree may have very little to do with your new career. This is most true for humanities and social sciences PhDs. The PhD has become mainly a labor market symbol of a rare combination of traits: high intelligence + strong work ethic + advanced critical and imaginative thinking. Translation: we’re superb, intrinsically motivated individual contributors in an ocean of externally motivated, average-IQ worker drones. I used to think this last bit was just snobbery until I entered the American workforce. Oh. My. God. No wonder I got promoted five times. And I always hired people with strong work ethics as well. That honestly matters more than raw intelligence to anyone managing a team.

Like most Americans, PhD holders view their degree’s status power based on how the following variables play out: how much income they receive, the prestige of their institution in their social world, the deference they receive at work, and the general prestige they have in public.

Most PhDs do not earn 1% incomes, work at high-prestige institutions (e.g., Yale), have elite media brands (e.g., Jonathan Haidt), or have high status in their workplace; virtually none have all four. When I was at Harvard in the early 1990s, the late Stephen Gould’s colleagues did not consider him a serious biologist. He was a media sell-out to them. His books are excellent. Gould provided an outstanding public service during the back half of his career by making evolutionary biology exciting and accessible to everyday readers. No one remembers his jealous, snide colleagues. Status incongruity even for the “celebrity professor.”

In Part Two, I’ll explore how different career paths involve different trade-offs that my PhDs generation was unprepared for.

1

1US Census, CPS Basic Monthly January 2025.

2