Exorcising the Academic Curse

Note: This is the final piece in a two-part essay. See Part 1 at this link:

When I received my PhD in February 2002, my perception was that most doctoral students in ANY field wanted to settle down in an academic research position. At least initially. This was the high-status goal for most of us when we started our programs in the 1990s.

As far as I know, no one collects data on doctoral students’ intended careers when they start out. However, federal data on PhD recipients’ immediate plans indicate that the percentage of people who have lined up an immediate academic or postdoc position has shrunk dramatically (from 63% in 2003 to 35% in 2023).1

The universe is NOT rewarding kids like me who naively dreamed of becoming a Professor of Something. And it has not been doing this for some time. It appears that doctoral students are figuring this out earlier in their programs than I did.

Academia’s Abdication of ResponsibilityOver the last thirty years, almost 1/3 of all PhD recipients have no clear commitments upon graduation. The data has slipped magnetically around the 30% mark in the past forty years but does not want to escape it. The percentage is especially high in the fields that the private sector does not desire openly (e.g., the humanities).

How the hell do we let students wind up in this situation in such large percentages? These are not stupid people, needless to say. They are more resourceful than the average Joe, especially if they closed on the degree.

Whether you are floating in this anti-climactic phase after graduation or have decided to leave an academic position that is killing you or a family move forced you to abandon tenure, here is what it feels like to say goodbye -

Instead of heading off to a new post, our family moved back into my parents’ basement. It was an anticlimactic end to my academic career and, frankly, one of the hardest periods of my life. Many professors don’t appreciate how difficult leaving academe can be on their students who expected to be professors. It can be a devastating loss of purpose and identity.2

The psychological devastation hinted at above may seem trivial to anyone who grew up in a working-class home, an inner-city home or an abusive, broken home in any social class. Boo-hoo, some readers will cry sarcastically. Yet, that’s the strange thing about the inner life - our assessment of our social status and psychological safety occurs first inside our minds. And this assessment is entirely relative to our original objectives.

Our misery can persist with no external validation of it—a true curse of the human imagination.

As adults, imagining ourselves in a future state we know nothing about and registering our feelings there isn't easy. Humans are more sophisticated at adaptation than squirrels or mosquitoes, but…we have limits, too.

It is even harder to imagine a happy future state beyond academia when NO ONE TALKS ABOUT leaving academia. When your peers never ‘return’ from beyond the cult to inform you. When the cult abandons you silently, my advisor never followed up after graduation and the final round of recommendation letters she wrote in 2001 (before I jumped out of the castle tower window).

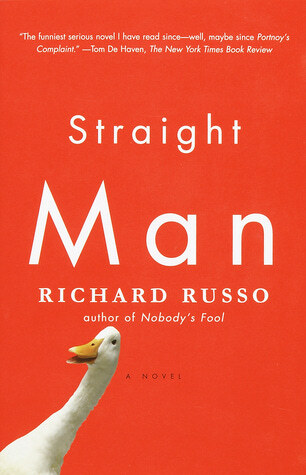

Should I have been surprised? No. And I wasn’t. After all, this person had confessed to me in my early years that “I originally wanted to be a writer, but I have to pay bills!” My advisor wanted to be a novelist but ‘settled’ for tenure in academia, where she ‘advised’ the kid who wanted to be a Professor of Something since he was 16. Richard Russo could have used that conversation in one of his satirical take-downs. I didn’t think it was funny at all, of course.

Academia has always been a vestige of medieval guilds, such as the artisan trades, medicine, law, and architecture. If a Master accepts an Apprentice and the Apprentice does the work, there is a straightforward process with which to advance. The path is laid out. The steps are known. You knew about most of them when you applied to your doctoral program. The goal - tenure - is absolute security in which to do your work.

What you didn’t know, perhaps, is that, unlike a medieval guild, the people in authority today in academia are not committed to everyone’s fate. Their commitment is to drive revenue, supporting their department’s budget and salary. Instead of a protective guild, each step on your journey is a chaotic weeding-out phase with no clear support - and not just during the normal weeding-out phase before being advanced to candidacy.

The first weeding out is no longer structural. It occurs inside the noncommittal relationship between you and your advisor. If this relationship does not spark more or less erotically, however figuratively this transpires, it is very unlikely your advisor will advocate for you like you need them to when it counts.3 You will not become the ‘anointed.’

If you also do not commit to following up on their work, you’ve thrown away the essential tool of flattery. Your advisor formally handed you your dissertation topic in previous eras, and you accepted. The system ensured alignment with the advisor. Smart. By the 1990s, though, America’s culture of lifestyle choice flowed into topic selection, creating the essential permission for advisors to abdicate responsibility for the students they agreed to train. “Hey, that’s not a topic I would pursue” is rarely spoken in a false, noncommittal advisory relationship. Not when everyone could use your tuition dollars.

At the other end of the career ladder in academia, budget cuts and the bizarre circus of ‘cancel culture’ assure PhDs that tenure is no longer permanent.

Academia has become no different than the private sector startup world.

You, the candidate, are the startup. Everything else is negotiable. Everything. You are supporting yourself in a market of oversupplied talent with little obligatory vetting or support from those in authority.

The guild has closed. Capitalism finally broke it.

How to Exorcise The Academic DemonToday, there are more resources for PhDs who need or want to escape the academic clown show, even though they, like me, made this decision at the end of their doctoral journey.

The key to making this work is to embrace being a startup in bodily form. Become that startup hustler you probably once despised as ‘crass’…and…you will ultimately conquer all the petty resentments of doctoral training. Maybe.

As a solopreneur and bestselling business author, I now have more interpersonal, financial, and emotional autonomy than I imagined I would receive with tenure. All I had to give up was an extreme definition of intellectual autonomy. I never enjoyed teaching much, so that was easy to let go of. Looking back, it’s crazy that I fought this change for so long in my head.

“Become the CEO of your life and career” - Our Canadian Friend (see quote above).

Superb advice, but easier said than done for a group of adults who skew highly introverted, suck at networking, and have traditionally gravitated to highly structured settings (i.e. a Guild environment).

There are at least seven kinds of PhD labor. Each has an internal status hierarchy primarily based on the prestige of the host institution. I won’t waste your time mapping that out for you.

The key is that each path demands one or more of the four trade-offs I introduced in Part 1. Some trade-offs are more severe than others.

Trade-Off #1: Intellectual autonomy is inversely correlated to making a lot of money

Trade-Off #2: Collaboration versus working alone.

Trade-Off #3: Intellectual idealism versus highly pragmatic concerns of the real world.

Trade-Off #4: The content of your degree may have very little to do with your new career. You have to become an expert all over again.

I leave it to you to see which of these doctoral clans suffers the ‘worst’ trade-off mix and who benefits the most. I’m too biased. Clearly.

The Intellectuals—This was my original objective and the objective of virtually all doctoral students in the humanities and social sciences. They are the super-opinionated ones who often hate teaching. They engage in vicious intellectual debates for sport and honor. They won’t discuss their ‘work’ with mere plebians. They are obsessed with intellectual purity and have difficulty trading this off in pragmatic work outside the academy. Very rarely, an Intellectual like Jonathan Haidt will write a nonfiction bestseller and morph into the Intellectual’s most highly resented form - the Media Intellectual. They will then quickly trade off many Intellectual friends (e.g., Stephen Jay Gould) and find new ones (desperate to get into the media themselves). These PhDs toil in total obscurity, often with barely grateful students. Even their University Press books rarely sell. Their intellectual labor is for a nanoscopic tribe, frequently highly critical and resentful. Their pay has eroded substantially to the point of outright insult.

The Teachers - This important clan gets paid the worst because they work in non-research positions in nonprofit institutions. Tsk. Tsk. Despite the financial trade-off, the Intellectuals look down on them for obvious reasons - they produce no intellectual output. They transmit the Intellectual’s output to students and savor the feeling of remaining an arbiter of ‘powerful knowledge.’ But the other clans just feel bad for their shitty salaries. If they do not engage in serious hypergamy, their life involves trading off income and prestige in their field. ‘Marry a surgeon or banker’ is my advice. Teachers LOVE their students. Seriously, they do. At my old private high school, these folks even write books to achieve some form of intellectual catharsis. Good for them. We Knowledge Workers pity their salaries but envy their ability to savor the Intellectual goods daily.

The R&D PhDs - These folks work in corporate labs or as mathematical modelers on Wall Street. They are ‘evil sell-outs’ to the Intellectuals, Teachers, and NGO clans. R&D labs are where the reliable money is for PhDs, especially if you can eventually run your own laboratory department funded by a major corporation (or, even better, by rich angel investors). Think of lab scientists in leading-edge labs at Pfizer, 3M, SpaceX, etc. - these PhDs often engage in era-defining research and are paid accordingly. But, there is also an army of corporate R&D PhDs in the less glamorous worlds of consumer goods, industrial manufacturing, and packaging. This work is crucial to the business models and cost containment of companies that make essential goods (e.g., groceries, steel girders, Post-It Notes). These PhDs can also easily point to their ‘work’ in the real world and be proud. Their invisible work becomes visible, unlike the work of the Teachers and Intellectuals. This can be very satisfying, more satisfying than much of the work done by the next clan I want to portray.

The Knowledge Workers - This is where soft social science and humanities folks like me end up. These firms or agencies have ways to use creative and highly analytical brains for all sorts of corporate purposes, from market research to strategy consulting. But they earn a wide salary range. The problem is that an enormous amount of this “work” is what David Graeber describes in his bestseller - Bullshit Jobs. I’ve never seen so much meaningless PowerPoint as I have in the market research sector. When you have to pretend to have a debate with an ad agency twit about human behavior, it’s infuriating and insulting. The Teachers have far more daily fulfillment than these folks and experience less weekly status humiliation. My experience is that the more a Knowledge Worker secretly cares about being an Intellectual, the more they will flounder in rage and the less they will advance and earn in the private sector. Once you can sell knowledge to clients by taking their analytical needs seriously, you can start making good money. Of course, if you are that good and client-focused, you should consider becoming a self-employed consultant. This took me way too long to realize and then execute. Very few of us pull this off. I wrote a book to do it. Not everyone has that opportunity. The worst thing about this clan is that almost all of them do permanently invisible work that leads to nothing in the real world. Maybe a package design on a food product. Maybe. Knowledge Workers make the most trade-offs until they can work for themselves. Because of this, I suspect they are grumpier on average than the Teachers but less so than the poorly paid Intellectuals.

The Startup PhDs - These are the genuinely sexy PhDs, the folks lending their degree halo onto all sorts of entrepreneurial ventures, from on-demand therapy apps to meal replacement nutrition products to SpaceX. They work closely with management and may even be co-founders. If you want a public face and many media opportunities, this is the opposite of the R&D folks toiling in corporate obscurity. I suspect the narcissism index is a wee high among these PhDs. They often make a lot more than the R&D clan, so it tends to be where more experienced, ambitious R&D people go. They are also satisfied with performing visible work worldwide, unlike the Knowledge Workers or Teachers. I’m not sure many feel that they reduced intellectual autonomy because there is a strong alignment between their doctoral work and what they now do. I suspect my elder son may wind up in this clan.

The NGO PhDs - Many of my non-academic anthropologist peers work in international development and foreign aid. They often enter doctoral programs intending to do this. Honestly, it is a more thoughtful approach to your entire program than thinking you’ll be the rare diamond who earns academic tenure. They work in : elite global organizations (e.g., WHO), mega-funded philanthropies (e.g., Bill Gates Foundation), famous NGOs (e.g., World Wildlife Fund, Doctors without Borders), and invisible NGOs (e.g., why would I give you an example?). NGOs perform invisible work mostly abroad, but recipients are grateful for the most part, like recipients of missionary schools and hospitals in prior eras. These folks are not super well paid, but better paid than the Teachers and Intellectuals. I suspect they experience few trade-offs because they are often not interested in Intellectual autonomy or financial glory. I suspect many equally well-paid Knowledge Workers envy the sh*t out these folks.

Government PhDs - This clan gets paid well from the start, better than many Knowledge Workers. But they do have to let go of the desire for intellectual autonomy. Quickly. If they intended to wind up here (and some in Sociology do), then it can be very satisfying and secure work. Government work also leads to more visible public outcomes than the Teachers, Intellectuals and Knowledge Workers experience. These folks can have real authority inside federal agencies where their PhD often confers daily status in the workplace. I can not say the same for the Knowledge Workers or Intellectuals. One other trade-off his clan makes is long-term salary upside. It is entirely dependent on limited promotions. Hence, the most ambitious continue to leave for the private sector (including the NASA to SpaceX parade).

Many career paths involve trade-offs, but the PhD experience is pretty extreme in large part because this degree magnetically attracts a combination of maniacal focus, stubbornness, and intellectual idealism. This is both a weakness when change is necessary (we react slowly) and an enormous superpower when the way to make your PhD work for you long-term is to become the “CEO of your own career.”

PhDs today are used to institutional neglect and indifference, which is precisely what the modern workplace feels like for many. Bring it!

1

1https://ncses.nsf.gov/surveys/earned-...

2https://www.insidehighered.com/advice...#

3Without trying, I collected at least five anecdotes of women fucking their dissertation advisors. I’m willing to bet they all got to tenure-track positions. Needless to say, unless you are a gay male, this approach is unavailable to men (who are rarely attracted to women 10-15 years older).