James F. Richardson's Blog, page 3

January 8, 2025

Episode 17 - Anti-Individualist Counter-Trends

The crux of America’s problem - lifestyle fragmentation makes feeling obligated to others more difficult than ever before.

…the American individual as a rights-enabled consumer interested in defending her lifestyle autonomy against any confining claims by family or community…The result of training up a nation of rights-enabled consumers is a bewildering …

January 4, 2025

The Inevitability of Pharmacological Solutions to Obesity in America

Wegovy injection stick; courtesy of Shutterstock

Wegovy injection stick; courtesy of ShutterstockA tiny segment of American wellness advocates laments the spread of Wegovy and similar weight-loss drugs. This is the same elitist group that lamented the spread of bariatric surgery in the 2000s. These folks sit high on their nutritional thrones and fervently believe that ‘real’ people should only use food as medicine. They also detest the pharmaceutical industry, partly because they are often right when achieving significant health impacts quickly and conveniently for specific subpopulations (e.g., insulin for Type II diabetics). And drug regimens are far, far easier to adopt than large-scale dietary overhauls. I’ll explain why in a bit.

The more capitalist of America’s wellness influencers, like Dr. Mark Hyman, are pushing DTC supplements that they claim boost GLP-1 production ‘naturally.’ For example, Himalayan Tartary Buckwheat Sprout Powder is Hyman’s go-to magic supplement. At $45 for 8 ounces of powder (i.e., presumably to dump into a smoothie), this product is absurdly priced for anything approaching mass adoption, let alone adoption by the severely obese who skew low-income in the U.S. For comparison, cheap whey protein powders with mass distribution only cost 60-75 cents per ounce (e.g., GNC Whey), not the $5.63 an ounce Hyman’s marketing machine charges for Tartary buckwheat powder.

I have worked with alternative nutrition advocates as clients and, more intimately, as former colleagues. Theirs is an insufferable, very American snobbery because it’s anchored in voluntary lifestyle choices. It feeds all manner of online and offline virtue signaling. Ironically, as left-leaning social critics, these alternative nutrition geeks always seem to promote individual responsibility whenever these weight loss ‘shortcuts’ are mentioned in conversation. They mutter things like:

You have to put in the work

You have to cut out the junk and the “crap”

You have to alter your diet alone, if necessary

You must pick the morally superior diet, the most nutritious possible, exceeding FDA guidelines and venturing into a neo-Japanese extremism

The message of modern nutrition influencers derives from the ascetic, will-power-based dieting ideologies since the 19th century and an older belief in the Protestant work ethic. Michael Pollan and Alice Waters are their heroes. I can distill their philosophy down to:

Eat mostly plants.

Favor raw plants.

Don’t eat much.

Avoid packaged snacks and convenience foods in general.

Drink only water.

Few people in America eat this way. This is not visible, of course, if you live in West LA or Lower Manhattan.

Today’s nutrition influencers push modern nutrition ideologies to guide the recomposition of your daily foodways. These diet recommendations are not necessarily science-backed, yet most agree that these are the ‘healthier’ diets. Personal nutrition has also become competitive, a central part of the urban status game among educated people. Curating your diet is now as trendy as curating your social network: no more toxic foods or family members.

Quietly and in private, many of these nutritional geeks sneer at the ‘fatasses’ walking next to them at the mall or the airport. I’ve witnessed these comments all my life among upper-middle-class folks. Inevitably, the most condescending are the thin-fluencers (and always have been). The folks who say:

Eat like me. Look like me. (add optional “Bitch” for snide emphasis).

Besides enabling eating disorders, this cruel cultural logic among the educated, urban elite accomplishes something else - it points to the power of social accountability in getting the individual to commit, for a while, to ascetic body image ideals. It’s a group process to make it happen. Media imagery of thin people does not cause anyone to cut weight. However, having tons of “eat like me, look like me” people at your office may.

To chase skinny, you have to be in a social world where ‘thinness’ is not only an aspiration; it’s all around you. Where thin is normal, eating to be thinner makes sense. You will have visual reinforcement of your objective all around you. Yet, the overall rarity of skinniness in modern America also presents the mildly obese and even the merely overweight with a powerful incentive to regain their prior normal BMI status – join the ‘body elite.’ After all, many of us were thin once before in our lives. I was medically underweight in high school.

If, on the other hand, you are morbidly obese, the odds are pretty high that you live in an overweight social world - at work and home. Being thin will not seem very plausible in such social networks. With plus-size models appearing in more and more media content and commercials, you may feel relatively comfortable now with your BMI.

Here is one analysis that supports this view using the unique dataset of the Framingham Heart Study of ~12,000 adults:

A person's chances of becoming obese increased by 57% (95% confidence interval [CI], 6 to 123) if he or she had a friend who became obese in a given interval. Among pairs of adult siblings, if one sibling became obese, the chance that the other would become obese increased by 40% (95% CI, 21 to 60). If one spouse became obese, the likelihood that the other spouse would become obese increased by 37% (95% CI, 7 to 73). These effects were not seen among neighbors in the immediate geographic location. Persons of the same sex had relatively greater influence on each other than those of the opposite sex1

The intrinsic motivation most likely to cause the average obese American to do something radical with their diet to lose weight if they are obese is health. An elitist quest to become skinny or join the body elite is not likely to be either a) plausible or b) compelling to most of these folks. I know this because I’ve interviewed obese adults like this for market research studies. Their motives are primarily about eliminating chronic diseases and pain related to obesity. Health-oriented weight loss is about shedding chronic illnesses (heart disease, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, etc.) and extending longevity. It’s not about becoming skinny again. The more weight obese Americans want to lose, the more health-oriented and pragmatic their viewpoint always appears to be. It’s not about becoming a swimsuit model or snagging a shallow investment banker. Most of the obese skew older anyway; they have had more years to slowly over-eat and under-exercise. And their approach to dating is not as shallow as that of youth.

But imagine losing weight when your spouse, friends, and family could not care less about doing it themselves. You are alone in your quest, with maybe an app or a weight-loss Facebook group. You stand little chance of persisting with your dietary alterations long enough to derive much benefit. Why? Because the other people living in your house haven’t changed their diet. So, you must shop for the foods you probably need to keep out of the home. At the very least, you have to cook meals for yourself and then for everyone else (if you are the primary cook). This is a pain.

Source: Scarlett Bendixen Blog - https://madeitateitlovedit.com/organi...

Source: Scarlett Bendixen Blog - https://madeitateitlovedit.com/organi...Being surrounded at home by the food culture you’re trying to overcome is the primary reason diets do not last (see top two drawers above). The second reason they fail early is that the dieter is miserable and not socially rewarded enough to continue them for more than a few months. While researching some chapters for my recent book, I learned that only two branded diet programs (Jenny Craig and Atkins) have been proven to sustain measurable weight loss for a year. And, then, they, too, fail. Dieters either become bored or feel confined, or American foodways simply push right through the individuals’ dietary defenses. Call it entropy if you like.

If you are going to make radical dietary changes, you need extreme intrinsic motivation (e.g., painkiller-proof rheumatoid arthritis due to morbid obesity), extreme ideology (veganism), or operate within a near cult-like social network where the slightest fatness is cause for teasing and/or banishment (e.g., a New York fashion model).

Living alone becomes your best bet in these situations where your social network is uninterested in your quest. As a solo dweller, you can control your entire pantry and eating day without sarcastic comments, in-home temptations, or direct interference (i.e., being dragged out to the Cheesecake Factory). But you still need powerful intrinsic motivation. Restructuring your diet alone is mostly a privilege of middle-age and old age in America, a time when you can more easily afford to live alone. I have interviewed multiple successful weight-losers who lived alone (one in a 55+ community) and could drastically reshape their foodways with minimal interference. Their homes become a sort of temple to weight loss and weight control, which their friends and family learn to respect (as guests, not residents). And, as a solo dweller, it is very easy to avoid hosting large food-centered gatherings. You tend to be someone else’s guest and have total control over showing up versus a family where tradition may compel you to host various holiday feasts that further tempt backsliding.

If you have to live alone to best restructure your diet for weight loss or weight control, it is a weird solution, albeit successful. And, perhaps it is a tragic necessity in the long duree of human history that our overabundance of high-carb snack food (and cheap food in general) requires circumstances so extreme to make dietary weight loss feasible to sustain. If you can create a domestic cult of one, it might possibly last.

In America today, the lone dieter trying to lose a lot of weight through dietary modifications (and perhaps exercise) has to overcome:

a lifetime of palate adaptation to excessively salty, fatty, and sugary snack foods and to meals stuffed with meat and carbs and minimal high-fiber vegetable content

the continued, problematic eating behavior of household members

the constant presence of ‘enemy foods’ in the home

shopping for those ‘enemy foods’ so others are happy/content

constant visual reminders due to the over-distribution of tempting junk food in vending machines, C-stores, cash register displays at supermarkets, etc.

exposure to ‘enemy foods’ at the gatherings of friends and family

lack of any proximate role model for extreme weight loss in social networks of the obese and overweight

limited, effective social accountability (i.e., lots of people you love are ready to supply well-intended rationalizations for your lack of weight loss)

That was just a list of cultural inhibitors here in America, one of Earth’s fattest nations, oversupplied with cheap calories and people who love to eat out of stress. This is a horrendous country in which to attempt a 20% loss of excess body weight due to visceral or adipose fat. American food culture is a constant setup to failure without one of the extreme motivators I listed above.

Finally, exercise can help you lose a lot of weight, but only extreme amounts. According to Harvard Public Health research, it takes 3,500 burned calories to drop one pound of fat.2 That’s a ton of calorie burn compared to the average person’s concept of exercise. A 30-minute neighborhood power walk at 4 mph does more for the abdominal core strength than weight loss. This kind of activity burns anywhere from 150-200 calories per 30-minute increment, depending on your body weight. This does nothing to burn fat. Nothing at all. And it only takes a handful of trail mix to nuke its effect.

To drop 25 pounds, you need to burn 90,000 calories through exercise! That is like power walking at four mph for…(drum roll)…for 2,400 miles!! No one who lives in an obese social world, surrounded by non-exercisers, will get in anywhere near 2,400 miles of power walking without extreme motivators like a ‘death sentence’ from their primary care doctor (this does work, BTW).

Even my wife and I, who go on four-to-nine-mile trail hikes twice a week, are not losing weight. We’re just maintaining it well. Those ‘killer’ hikes burn 1,200-1.700 calories or maybe half a pound of fat. The math is depressing. But remember, it took years and years of slightly excess daily calorie intake to put on 25 pounds. Years. So, should it take anything less than years to shed it?

The weight gain did not happen as hastily as we desire to lose the weight.

Most Americans will never put in 2-3 hours a day of weight training and cardio six days a week to burn 3,500 calories every two days for months and months. If you could burn 1,500 excess calories a day through exercise AND switch to a low-carb, high-fiber diet, you’ll still eat more due to exercise. Still, you should be able to lose a fair amount of weight in 1-2 years—a massive disciplinary commitment in the cultural context of America’s consumer culture of passive, hasty consumption.

Who the hell is going to put in that effort? We are not college athletes. We are not motivated like Mark Wahlberg trying to shred for a $30M film contract. That’s a powerful motivation none of us mortals have. A lot of us would do extreme things to capture $30M. Don’t count yourself out too quickly, reader.

Retirement, ironically, is the best time to tackle this kind of extreme exercise, as my wife reminded me this morning. But, then, exercise becomes a part-time job of sorts. I rode my road bike 200-300 miles a week in college. So, I’ve done this extreme exercise before. I even scratch my head thinking about doing that in retirement. Would I really do that again to shed 10-15 pounds?

Once pharmacology invented a weekly injection (and soon a daily pill) that can have the dramatic effects of a year of extreme exercise or bariatric surgery, readers should understand why we gravitate toward this approach.

This is why Wegovy and similar GLP-1 agonist injections are experiencing exponential growth in new prescriptions.3 It’s spreading so fast, it’s hard even to track it.

Yes, we won’t become thin. But medicine will overcome the enormous forces hellbent on reverting us to old junk food habits without the extreme time commitment of heavy exercise regimens. I have no judgment anymore about those who choose bariatric surgery or GLP-1 agonist medications, especially if they are in a social network fighting against them.

Do you know anyone taking GLP-1 drugs? What are folks experiencing?

Recent Podcast interviews about my new book!

Discover More w/Benoit Kim - The Dark Side of American Individualism

EZ Conversations w/Furkhan Dhandia - Cultural Contrasts and Individualism

Meredith For Real - Is American Individualism Over-rated?

1

1https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17652...

2https://www.healthline.com/health/cal...

3According to my analysis for the Food Institute - 4.8% of Americans have ever taken Ozempic, Wegovy or another GLP-1 medication in order to lose weight. And 2024 is becoming the breakout year for GLP-1 anti-obesity medication prescriptions. Doctors wrote roughly half a million new anti-obesity GLP-1 scripts between Jan. 1 and June 30, 2024. This rate then nearly doubled between July 1 and September 30, 2024. In 2024, script acceleration will yield more than 2,000,000 new anti-obesity prescriptions for these medications. This constant acceleration is a strong sign of steady repeat prescription usage by a growing patient population that is doubling every six months. With the reliable Q1 surge in dieting behavior in America, this acceleration is likely to continue into 2025. In 2024 alone, roughly 1% of U.S. adults started Wegovy and similar meds in order to lose weight. Note: detailed sources and methodology are in the linked article.

January 1, 2025

Episode 16 - The Problem With A Culture Built On Never-Ending Growth

I was too busy curating my best life to hear about your alcoholism! My bad! Talk soon!

A real human community does not tolerate the above behavior. The challenge in 21st-century America is that our entire culture and economic system focuses our non-work time on consuming things, mostly passive media. We deprioritize maintaining relationships with those w…

December 28, 2024

A Secure Middle Class Is Autonomy's Fuel

Photo by Fons Heijnsbroek on Unsplash

Photo by Fons Heijnsbroek on UnsplashThe poor and the rich in complex, agriculture-based civilizations like ours have one thing in common: less interpersonal freedom than those born into the insecure middle classes. By understanding the psycho-social limitations of poverty and intergenerational wealth, we can better understand how middle-class heavy societies like America breathe “social autonomy” as a necessary fuel. And why we might unwittingly forsake it when it no longer delivers financial security.

So, let’s look at America’s social extremes for cultural insight into the vast middle of American society.

The Rich Live-in Lifestyle Prisons Based on Extreme Consumption and Public ReputationOnce wealth transfers across generations in quantities that make working for a wage unnecessary to support an expensive lifestyle, you are what I’m loosely calling “rich.” I’m referring to intergenerational wealth. This definition excludes nouveau riche billionaires and millionaires like Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffet, and, on the low end of the continuum, my own father. They haven’t transferred anything. Yet.

Historically, the rich in agricultural civilizations controlled vast amounts of income-earning land. This was the economic fuel of all aristocracies and is the original form of intergenerational wealth.1 Today, though, stock market investments create intergenerational wealth like never before. Land converts to investment cash pretty quickly. One result is America’s ~7,000 Family Offices, which, in the aggregate, control $7.6 trillion in wealth (and who quietly fund some of the early-stage companies I work with).2 The tiny percentage of people who have either kind of intergenerational wealth (land or investments) tend to live in prisons of social status maintenance, severely restricting acceptable marriage and career options. They are raised to see narrower, ‘suitable’ options. This is even true in America today, where the “rich” desperately try to mask their enormous economic power in public. Anderson Cooper can ‘work’ for a living and be gay, sure, but he can not marry a gay oil rig worker (unless his name is Robert Dupea). He was raised not to see the latter as a valid option.

The “rich” (i.e., transgenerationally wealthy) lose a lot of social autonomy because society has socially captured their families. What? Since intergenerational wealth is almost always tied to intergenerational institutions, titles, and status roles in local society, local communities expect the “rich’ to perpetuate a particular ultra-elite lifestyle. We expect the Rockefellers and Ambanis to live like the “rich” because they have always been “rich people.” We expect the rich to perpetuate their ultra-wealthy lifestyle like the sun rises and sets. And we gossip loudly via the media whenever one of their members forsakes the clan (e.g., the 24/7 crazy coverage of Prince Harry’s renunciation in 2020). Even if your “rich” family is not well-known nationwide, you are usually known locally as an intergenerational wealthy family. The locals have captured you symbolically. For the rich, as I define them here, the vast majority of careers and sexual partners become “less than” and “unworthy” choices. You have fewer alternatives than the average person. You could pursue the unsuitable, yes, but you will lose status in your family, perhaps access to money and privileges, and, if disowned, transition to an outcast, middle-class lifestyle. The total capture of the “rich” occurs because it’s not just your family trying to contain you in your “rich” lifestyle - it’s most of society around you. You are a prisoner of extreme, society-wide expectations. If you’re a rich introvert, this has to be a truly bizarre form of hell-on-earth. This ‘capture’ haunts any individual who has fallen back into the working middle class because their parent squandered their chunk of the family fortune.3

Should a “rich” young person desire to rebel against a narrow range of acceptable careers (managing the family money, philanthropy, or the arts) or marriage pools (i.e., other “rich” people), historically, they have had to be willing to throw away a luxurious lifestyle and rebuild their social status from scratch on earned wealth.4 Very few rich individuals have ever made such status-demoting choices.5 Siddartha was an early documented case in ancient India (he became the Buddha of Indian legend). Patty Hearst was another rare example from 20th-century America; she wound up in federal prison. Prince Harry also rebelled in spectacular form recently, partly because he and his Hollywood wife have enormous social media platforms to generate ‘media money.’ He knew he could re-earn his consumption lifestyle very quickly.

Despite the prison of “rich” social status, Hollywood loves to make up fanciful aberrations for an individualistic, middle-class audience. A great example from the film world is Robert Dupea, a near psychopathic black sheep from a rich Pacific Northwest dynasty played by Jack Nicholson in Five Easy Pieces. These are the ‘rich folk’ Americans love - the rich who escape the lifestyle prison of being born rich and give their “family” the middle finger. Paul Newman demonstrates the imprisoned feeling of the southern “rich” in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof - a feeling made worse by coming of age as a young man in a highly individualistic, post-WWII America.6 Most of Brick’s school buddies probably did not bear his particular “rich boy” burden.

In America, intergenerational wealth has an odor of illegitimacy because we are now a fully realized, achievement-based society whose wealthiest people are usually the nouveau riche (the initial robber barons and, today - Musk, Bezos, Blakely, Ellison, etc.).

The nouveau super-wealthy have almost always eclipsed the mere “rich” in American social life, even with a lower net worth. We have fantasized about creating ultra-rapid wealth since Rockefeller and Carnegie. It is the most crass expression of our idealization of the self-made person.

Most of us assume the “rich” have more social autonomy because they have more opportunities to accumulate (and spend) wealth. This misunderstanding originates in a conflation of intergenerational wealth with wealth itself. The rich (i.e., intergenerational wealthy) have enormous consumption autonomy. That’s about it. In reality, though, they have traded off tremendous opportunities in lifestyle autonomy for opportunities to remain in consumption lifestyles almost no one else can sustain.

Most "rich” folks also desire to maintain the family's public reputation. This is very ironic in America, where your reputation in your field of work is the only thing that matters anymore. You can be a philanderer, a psychopath, an asshole, or a quiet abuser, and it won’t affect your personal life if it does not affect your career. We are not an honor-based culture reinforced by public shaming. However, the “rich”, even here in America, have all their behavior scrutinized, as all families did in 16th-century England.

However, in modern society, you can not even have a family reputation to protect until wealth transfers across generations in massive quantities. This partly explains why the super-wealthy nouveau riche engages in some of the most eccentric, messed-up behavior you can imagine (and could care less what you think about their behavior) but not their equally wealthy, “rich” peers. Remember, the nouveau riche person is just a super-wealthy middle-class mind anchored in an individualistic achievement ethos.

It’s important to remember that this "rich" group is far less than 1% of any nation’s population (excluding the Vatican). It’s a super tiny group. We see them primarily in the media, not in real life.

The Poor Remain Trapped by a Lack of Earning Opportunities AND a Desire for ProtectionOn the other hand, the poor may desire a more comfortable lifestyle, sure, but few feasible opportunities to escape endemic poverty will ever appear in front of most of them. I say ‘feasible’ because escaping poverty involves -

Luck - those who escape poverty, when you dig around in individual cases, tend to have had some ‘dumb luck’ thrown in their lap at a young age. My father’s luck was having his working-class town placed inside the Hanover, NH school district, probably the best school system in the state in the 1950s. It is a perfect place for a high-IQ kid from a low-earning household to thrive. The second piece of luck was having a guidance counselor who insisted he apply to Ivy League schools with his 4.0 grades. Imagine being that good in school and not realizing this potential yourself. That is a key component of cultural ‘impoverishment.’ Someone must slap you into seeing the opportunities right before you.

Networking for opportunities - those who escape have to have some networking charm. They are good in school. They have a pleasant disposition. They do not display the anger that poverty continuously feeds. The raging A-holes in the ghetto don’t get middle-class opportunities presented to them by anyone. Instead, the angry will more readily see gangs as a productive way to earn money. The least angry poor who do well in school are suited well to escape. Among this tiny pool, those who naturally look for opportunities and desire to ‘get out’ from an early age are best suited. This also leads us to those least involved in local social networks in poor neighborhoods.

The partial or total abandonment of natal family and local social networks. Again, no one likes to talk about this, but any social historian knows what I’m talking about. In America, this abandonment of family can be and has often been emotionally severe for the socially mobile. The pull of impoverished social networks is immense, unlike in middle-class suburbs where everyone is quietly raised to flee the locality for opportunities. Yet, the poor (or even struggling working-class individuals) often need the local community's protection and the ability to share resources. The poor have a powerful incentive to be more group-oriented and less individualistic to survive. The most violent inner cities still demonstrate this every day. Escaping poverty requires a particular kind of neurology - one that is ultimately pretty damn antisocial. I say “antisocial” because abandoning one’s natal social world is about throwing away access to protection and resource-sharing (i.e., going it alone). Most of us leave our hometowns so easily that we think this is normative behavior nowadays. Those who do not bond easily with others, therefore, most easily escape poverty. The psychopathic and high-functioning autistic have a considerable advantage here (yet no social mobility experts I can locate ever discuss this possibility). These abnormal folks do not have the oxytocin chains binding them to their natal families. These emotional attachments keep some from pursuing opportunities put before them - opportunities most likely requiring long-distance resettlement.

The more your everyday life is survival, the more you will see others in your world, your family, as sources of protection and survival. This is a huge psychological inhibitor to escape that few acknowledge. You need the ‘luck’ of opportunities - elevators out of the pit - but you must be psychologically primed to see them as positive. In reality, many poor and disadvantaged folks find these opportunities downright terrifying because, to pursue them, you must let go of the “village.” Steinbeck was one of the first American writers to depict this emotional capture of the poor by the poor in beautiful, almost alluring prose that no one will ever replicate again (because today’s writers are too busy trying to reproduce their upper-middle-class social status).

Radical Social Autonomy is Largely a Middle-Class PhenomenonIf the rich are imprisoned by multi-generational wealth, elite social status, and costly consumer lifestyles they do not want to abandon; the poor are imprisoned by a multi-generational lack of opportunities to escape and by their strong attachment to natal social networks critical for basic survival (and emotional succor) in poor communities. A gravitationally heavy lifestyle pull is essential to the experience of poverty and intergenerational wealth. It is very hard to escape voluntarily when one is habituated to either.

So, who are the most autonomous members of a modern society? Free to work, love, and befriend as they choose?

It is the socially insecure middle class. These people must constantly re-earn their social status with each generation and their ability to consume as they did growing up. I am one of these folks. Our desire for maximal autonomy is born of a need to maximize opportunities for status re-earning. Our primal insecurity is that we need some kind of cash flow from wages or business earnings to fund our lifestyle. The money must continually come in. We do not sip on inherited wealth. Free-range careers and marriage strategies allow the middle classes to accumulate incremental chunks of social advantage. We have so many more alternatives than either the rich or the poor. This autonomy also allows people to make disastrous decisions and walk into tar pits of their own making. The middle classes are not surveilled as tightly as the poor and the “rich” are. This is why the most nervous social climbers tend to be highly religious, even fundamentalist. Deep down, they know that excessive autonomy is dangerous for individuals, even if it allows them to earn a better lifestyle.

A middle-class adult marrying an upper-middle-class person accesses an enhanced consumer lifestyle and more financial security. This is just one example of how broader life choices fuel greater social autonomy for those not stigmatized by poverty or socially captured by extreme family wealth.

The root of the middle class's need for autonomy is social and financial insecurity:

The middle classes are always financially insecure, even the intergenerational middle class.

The “rich” do not maneuver for financial security. That is assured from birth.

The “poor” never have financial security because they can not access middle-class social networks for marriage or middle-class employment.

Radical middle-class autonomy appears most eccentrically among the children of business owners and professionals (across cultures and time). The most cash-flow rich of these families are most likely to raise the most autonomous wanderers, entrepreneurs, and eccentrics. The upper-middle-class family’s relative lifestyle comfort when they were growing up (think upper-middle-class) confuses their children into a sense of financial security that the poor never have. They take more risks to re-earn their social status and consumer lifestyle. They have some cash safety net from earned parental wealth to warrant taking these risks. And, for the most part, these more affluent middle-class folks generally do a good job of reproducing the lifestyle they grew up with (or enhancing it). They had every advantage in preparing for the competition to re-earn their status. Sometimes, though, they slip—more than we Americans tend to discuss. Why would we discuss an autonomous failure?

The French Revolution was arguably the most violent cry of a repressed proto-middle-class in modern times. In the 18th century, social class consumption at modern middle-class levels involved a tiny % of any European society. This early, cash-heavy, urban middle class was buried politically inside France’s Third Estate (mostly landless peasants). These nouveau riche businesspeople had above-average wealth but limited voting power, no more than a peasant (!). As this class of business people and nouveau riche grew in a booming 18th century with accelerating global trade, their political frustration became impossible to contain. Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities is a searing, brilliantly written depiction of how the French Revolution began among the literate urban business elite, not the illiterate, rural peasantry. Disenfranchising the middle class is a recipe for disaster no modern, democratic nation would ever consider today. It’s now considered that dumb of an idea, except in Venezuela and Syria.

A vast middle class can not form in any nation without radical autonomy being possible for most of its citizens. Without this autonomy in careers and marriage, individuals can not maximize their opportunities to re-earn or slightly upgrade their consumer lifestyle.

The irony here is that nations built on a vast middle class also morph into societies featuring mass status anxiety and interpersonal status competition. The latent fear of financial insecurity is more palpable among the middle class than the poor because the middle class generally has sporadic financial security. They taste it and have something to lose. Talk to someone who has gone in and out of financial security, and you will not find a ‘woke’ campus activist.

When too many in the middle classes feel perpetually insecure financially, when their career and marital choices don’t guarantee financial security, a nation harbors a ticking time bomb. This is because the upper-middle-class, though now larger than ever in American history, can not contain the frustration of middle-class insecurity. We can only ratchet up our spending to create the appearance of a thriving macro-economy (weighted bizarrely to the spending of the “rich” and nouveau riche).

If you build an entire cultural ecosystem around middle-class autonomy so that individuals can pursue financial security, but then it stops delivering this outcome to a large percentage…then…the appeal of fascism and authoritarianism is remarkably easy to understand.

Even in a nation like ours that fought fascist Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union.

NEWS

- I recently gave a podcast interview about my new book that may interest many of you. It exposes the trade-offs the middle class makes in being highly autonomous social actors. It’s not normal in human history and we are still not good at figuring this out. We increased financial security for the majority, but at what cost?

The original, award-winning film starring Paul Newman and Elizabeth Taylor was adapted from a Tennesse Williams short story - “Three Players of a Summer Game.”

2https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam...

3This happens in America more than we acknowledge. I speculate that it happens more in our inheritance system than in others. One fascinating aspect of the American “rich” is that our bilateral inheritance customs have vastly expanded the number of “rich” offspring who can quickly sponsor multiple intergenerationally wealthy family lines. We do not automatically condense wealth control onto one male offspring. Our open-minded inheritance model encourages the broad spreading of wealth in the first generation of offspring (e.g., the Walton family), tons of resulting family infighting, and, potentially, a rapid squandering of diluted wealth (another fascinating American tradition few discuss publicly). The American approach does not ensure the inherited children have had any serious financial management training (versus a single male inheritor model where the boy grows up trained intensely to manage everything). The result is that third generations can witness individuals falling back into a middle-class lifestyle but with an ironic surname.

4Since the early 20th century, the ability for the rich to marry partners from affluent upper-middle-class families (including the children of the nouveau riche) has expanded their marriage pool a lot (vs. the aristocrats of the pre-WWI era).

5This discussion excludes inheritance systems where the eldest son captures all the inherited wealth and involuntarily creates siblings without direct access to family wealth.

6This 1958 film derives from Tennesee Williams’ short story - Three Players of a Summer Game

December 24, 2024

Episode 15 - A Diagnosis of American Individualism

As we have allowed ourselves the freedom to skip dinner, snack all day, and fine-tune our ingredient aversions, we have also allowed our foodways to become a moral and aspirational battleground that divides us from others…Individualism has made eating incredibly complicated and community more challenging to assemble in a very simple act: sharing a meal. - p. 312, Our Worst Strength

This is Chapter 32, the. master summary of all my book’s key points in narrative form. The book is a not solitary argument unpacked tediously over too many pages. It’s a fact-rich, sweeping exploration of how individualism operates in everyday American life, especially the glitches.

If you have too many unread books, let me read mine at your convenience…I’m almost done releasing it episodically— just a few more episodes to go! Upgrade that subscription to a paid to access the entire audiobook experience.

December 21, 2024

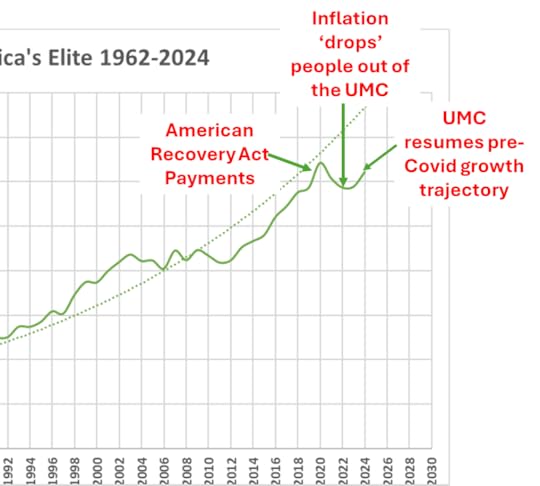

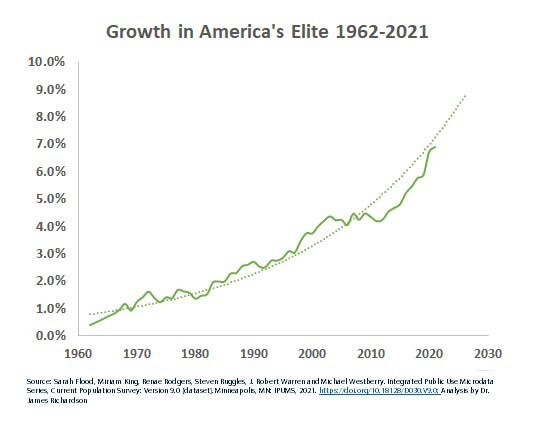

NEW DATA - Upper-Middle-Class Takes A Punch But Resumes Growth

Last week, I updated the analysis of a massive piece of Census analysis I did in 2022 and shared it with you all. I thought updating the chart through 2024 using the Community Population Survey data would be fun - making a little snack for everyone.

Oops.

Instead of having fun, I spent most of yesterday pulling and re-pulling the data from the IPUMS portal (a website where you, too, can pull your own raw, cross-tabulated US Census data!). And triple-checking my work. This “fun” was a reminder that the only difference between an amateur and a professional is that the professional assumes they made mistakes, looks for them rigorously, discovers them quickly, and fixes them.

And so I suffered the professional route.

The chart I published in 2022 (i.e., last week) used inflation data that is now moot. That is why the data for 2020 and 2021 are different. I forgot about this last week when I hit “publish.” So, our story from 2020-2024 has shifted.

Note: the analysis here does not follow the same individuals over time. It follows an SES group - i.e., adults aged 18+ holding college degrees or higher in educational attainment and earning $100K in 2019 equivalent personal income. This income threshold has moved up to $125K personal income for all sources (including retirement, gambling, etc.) It's personal income (INCTOT), though, not household income. A dual-income upper-middle-class home today must pull in $250K or more to qualify.

Who are these fancypants people, you ask? Well, people like me who got fancy letters to add to their names and who managed to monetize these degrees eventually (I thought I never would for about five years). PhDs today, for example, almost all make $100K or more if employed full-time outside of academia.

Enough background. Here’s the updated trend in the proportional size of America’s upper-middle-class. Wow.

Sarah Flood, Miriam King, Renae Rodgers, Steven Ruggles, J. Robert Warren, Daniel Backman, Annie Chen, Grace Cooper, Stephanie Richards, Megan Schouweiler, and Michael Westberry. IPUMS CPS: Version 12.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2024. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V12.0; my analysis of extracted data

Sarah Flood, Miriam King, Renae Rodgers, Steven Ruggles, J. Robert Warren, Daniel Backman, Annie Chen, Grace Cooper, Stephanie Richards, Megan Schouweiler, and Michael Westberry. IPUMS CPS: Version 12.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2024. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V12.0; my analysis of extracted dataEvery time I look at this chart, I picture the Capitol from Panem. You’ll recall that Panem reacted to an American civil war with fascism, not reconciliation or a New Deal. The totalitarian state in The Hunger Games not only concentrated its elite in one Capitol City, it also ensured that any hint of poverty or struggle remained well beyond its fortified walls. Squeaky clean. The world’s largest gated community.

Americans, like our counterparts in India, Indonesia, or Ecuador, just live in elite enclaves and drive right by and ignore the homeless, the poor, and the forsaken.

The long-term growth in America’s upper middle class is nonlinear, doubling first by 1967 (0.8%), then again by 1983 (1.6%), again by 1999 (3.2%), and most recently by 2024 (6.4%).

America’s upper-middle-class is returning to its long-term growth trend (based on sources of income, not unrealized investment earnings or property wealth). It will be 8% of the general population by 2028.

It’s like severe obesity for an entire class system.

Remember, America’s upper-middle-class are the folks who are:

most likely to be voting Democratic (and who are mighty pissed off right now)

most shocked by the recent Presidential election (refer to the bubble effect)

most likely to socialize in an upper-middle-class bubble exclusively (at work and in leisure)

If we Zoom in on the onset of the pandemic, we see the roller coaster and its primary mathematical causes (assumed by the author).

Sarah Flood, Miriam King, Renae Rodgers, Steven Ruggles, J. Robert Warren, Daniel Backman, Annie Chen, Grace Cooper, Stephanie Richards, Megan Schouweiler, and Michael Westberry. IPUMS CPS: Version 12.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2024. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V12.0; my analysis of extracted data

Sarah Flood, Miriam King, Renae Rodgers, Steven Ruggles, J. Robert Warren, Daniel Backman, Annie Chen, Grace Cooper, Stephanie Richards, Megan Schouweiler, and Michael Westberry. IPUMS CPS: Version 12.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2024. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V12.0; my analysis of extracted dataSo, what happened here? Well, a bunch of things. The 2020 ‘surge’ is most likely noise caused by American Recovery Act payments pushing individuals above the threshold in my SES definition. Not that important. As inflation soared in 2022 and 2023, the minimum income threshold effectively increased because the dollar’s real purchasing power decreased, making it harder to ‘earn’ or maintain your upper-middle-class status at the ‘bottom’ of the group.

The upswing appears mainly due to a delayed employer reaction to inflation. The average employer COLA (cost-of-living-adjustment) in 2021 was 5.1%. And in 2022, it was 5.9%.1 That was a total net average raise of 11.3% across diverse kinds of employers. But inflation rose by 15% from July 2020 through July 2022! Hmm..this kind of behavior sounds familiar. Dickens wrote about this kind of boss…

In 2023, American employers faced open rebellion or woke up a sweaty pile of guilt. Because the average COLA rose last year was 8.3%. Double the rate of inflation!

Why does the boss take so long to get it in America? Why! The federal data is updated monthly, people!!

And now, by 2024, wages have finally caught up with inflation. And voila! The upper middle class is back to growing.

But wait…there is more to this post-pandemic roller coaster—the absolute numbers involved.

1.8 million upper-middle-class adults fell out of the upper-middle-class by 2022. While a bunch were those hugging the minimum income threshold and are mere artifacts of math, many others simply lost their high-earning employment due to post-pandemic realities we prefer to forget. My amazing wife was one of these people.

She has a Master’s degree and, for years, has earned well within the personal income minimum to qualify for this ‘group.’ She earned this elite income tier steadily until she contracted long COVID-19 on an unnecessary business trip in June of 2022. She then took disability leave and returned to work three months later, only to be laid off six weeks later as part of a structural layoff. The job was taking a toll on a virus-weakened body, so it was a blessing in disguise.

Then, she took a job as a high school nurse as she continued to recover from muscle spasms, nerve pain, and chronic fatigue. I’m proud of this adaptation because it was a massive slice of ‘humble pie’ for an ambitious career person to eat. It was a big identity adjustment for her because highly educated women do NOT like being financially dependent on a man. They prefer to pay their way, so to speak.

My wife went from a corporate remote job in a custom-built office shed to an on-site job in a poverty-stricken public school with its own full-time security force (and vehicles) and with enormous daily health needs in its student body. Every day, she deals with anything from epileptic seizures to kids in diabetic shock, to severely autistic teens injuring teachers, to fistfight victims, to kids high on THC vapes, to opioid overdoses in bathrooms. At least 2-3 of the above every single week.

The irony of this job assignment is that my wife is now better integrated with the local Tucson community in all its demographic diversity than I am, sitting in my air-conditioned office shed running a mid-six-figure internet-based consulting business by myself.

I still live in the upper-middle-class bubble. She is a genuine part of the community.

Is the upper-middle-class bubble threatening America’s unity male-dominated, I wonder? Probably. If true, is having America’s men so segregated from each other by class a good thing for our future? Our elections? After all, most civil conflicts and wars are tied back to male anger in human societies, to men being unable to compromise and resolve their differences—angry elite men, for the most part.

As I wrote last week, I do not think that having an upper-middle-class operate as this large of an internally segregated group is wise for any modern nation. It prevents basic empathy about those less privileged because it is too easy to avoid/ignore even middle-class people.

PS - I did not dive deeper into cross-sectional variables. But I suspect most of these 1.8 million lost upper-middle-class adults were highly educated women. I hold this hypothesis because women remain structurally underpaid (mainly because of the white-collar positions they get the most access to).

While we have serious problems with internal class divisions in America, my recent book takes you on a story-rich tour through a standard cultural set of practices and tendencies most of us do share. We may not have similar ‘lifestyles’ or ‘traditions,’ but we have similar all-American tendencies. We should understand them better.

1

1Social Security Administration analysis

December 19, 2024

Episode 14 - Small Household Sizes and Family Trees Without Branches

In this episode, I finish reading Part Six on the Decline of Family as a key contributor to our American approach to individualism. Family-centered cultures do not let members wander the country or globe and disconnect from weekly visitations.

Urban America features couples and individuals as the foundation of households, not families. We do not even li…

December 14, 2024

America's Real Elite Problem

Since the Great Recession of 2008–2009, national media outlets and think tanks have reported on the growing income inequality in the United States. Yet, the problem is more complex and troubling than just income inequality. Regulatory or tax solutions alone will not be enough to address inequality on the scale it is now occurring. Inequality is always about far more than money—especially the kind of inequality we’re seeing now in the United States.

When I began my second career — in market research— in 2003, one of my first clients was Whole Foods Market. At the time, food industry veterans mocked the chain and its ‘revolution’ in quality standards for the American pantry. Some even openly predicted that ‘organic’ was a pretentious fad that would blow over when the overheated economy reset. Most of these naysayers were white men in their 70s (now either dead or in their 90s). I bring this up because they represented the last generation born before America’s educated elite underwent a dramatic sociological and demographic transformation. Before things that seemed basic - food safety - became disrupted by new notions of purity (i.e. natural, organic).

The economy did bomb in 2009, but the organic food revolution kept growing right through it and has now only become more extensive in scale. As a field researcher for the food industry at the time, I noticed something in the home pantries of Whole Foods Market’s heavy shoppers (they call them the ‘Core’ shopper internally). These folks were both affluent and educated and almost always Moms with young kids. These young families reminded me of my own, growing up in Bedford, NH., in the 1980s. Except for one thing: the Moms were more likely to be post-grad educated, not just college degree holders. And they had lots of questions about people in authority. Not all of them were friendly questions either.

It made intuitive sense that affluent Moms would now gravitate to premium food choices simply to maintain social status. The 1990s consumer economy of trade-up, as documented by David Brooks in Bobos in Paradise, had already made this very likely. Yet, this didn’t fully explain what I saw in the field since I kept hearing a health-related critique of the American food system. This critique took off with the assault on hormones in milk and the parental fears it ignited among Whole Foods Moms. This fear fed off increasing distrust in America’s central institutions, distrust by educated elites themselves. All that education of Baby Boomers and Generation X generated a much larger group of critical thinkers unwilling to take institutional pronouncements at face value.

And this was also the generation who came of age during the 1960s and 1970s, experiencing the violent crackdown on civil rights and the tragedy of the Nixon administration and its crooked minions.

The more educated they were, the less they believed in traditional institutions. Some of this elite were also the children of Holocaust survivors, an experience that could only strengthen one’s distrust in authority and the “mainstream.”

After the birth of our first child in 2007, I found myself joining the ranks of Whole Foods Market core shoppers as a participant observer. And I became fascinated with how much a Whole Foods Market family spends each month on groceries. So, I started collecting our receipts as a non-representative but directional case study. And I was shocked to discover we were paying five times the annual grocery bill of a typical family of four at the time (per the available BLS data).

That’s some class privilege, for sure. But I assumed my home represented less than 1% of Americans who wanted to trade up this way and could afford to live like this. But was I such a rarified snowflake?

Five years later, in 2012, my consulting team and I looked into a related hypothesis triggered by Pew Research data on the shrinking middle class. Our publicly traded client base was concerned about stalled growth and the shrinking household reach of their brands. We suspected that a steady increase in organic and premium food consumption and declining purchases of formerly iconic food brands reflected upward mobility into the upper-middle-class elite's ranks.

So, who is this upper-middle-class elite (or upper class)? Social scientists generally like to use the SES (socio-economic status) concept when analyzing class issues. As the acronym implies, they use multiple variables to define various social classes, not just income (as seen so frequently in the media and in business).

So, the team I led back then at a market research firm used a) educational attainment and b) income as the components of our SES model. It yields about nine or ten SES segments, depending on how you define things. Why did we pick these two variables? There are a couple of reasons. 1) these standard demographic variables allow anyone else to connect the findings to many other databases since these two demographic variables exist in most surveys. Most importantly, educational attainment is critical because we know it leads to different consumer choices, especially as you approach the extremes of privilege and underprivilege.

Since 70% of our economy derives from consumer choices, it’s critical NOT to assume that adults with similar incomes behave similarly in everyday life. I know from prior corporate research that brand preferences tend to exhibit substantial divergence at the extremes of educational attainment, regardless of income. Education better predicts consumer choices than mere income levels. I learned this touring the pantries of America in person. So, I believe it’s critical to intersect education with income to understand better how we make big decisions, like who we live near, and small decisions, like how expensive our produce is. It is the unconsciously held rules behind all these decisions

Using these two variables, I originally defined the upper-middle-class in 2012 as the following: 4-year college graduates with $100K or more in 2012 household income. Notice that this definition deliberately avoids a narrow focus on the 1% over which the modern media loves to obsess for rhetorical impact.

And when my colleagues and I looked at this group in Census data, adjusting for inflation, we found it had doubled in size from 1991 to 2012

This doubling of America’s elite was remarkable and helped explain the dramatic, double-digit growth of natural/organic consumer brand purchasing (our client focus at the time).

But what has happened since then to the upper-middle-class, roughly the same group David Brooks popularized in his fascinating book- Bobos in Paradise? And more importantly, why do we care?

______________________________________________

I recently did a similar analysis of the upper-middle class. This time, though, I raised the class ‘membership’ standard and analyzed the group as individuals, not households, with $100K or more in 2019 total personal income. Raising the income threshold allows us to see a tighter group of adult individuals who have more than enough income to live in nice apartments (or homes with two incomes) and buy lots of discretionary goods and services.

For this updated view on the growth of the upper-middle-class, I had access to a 60-year chronicle of Census data from 1962 until 2021 (w/help from IPUMS at the University of Minnesota). When I ran the raw line graph last November, I nearly fell off my chair. I initially hypothesized that the upper-middle class had grown primarily in the 1990s and early 2000s. In fact, in 2012, I just assumed the growth in the size of America’s elite would decelerate. After all, the economy already appeared overheated coming out of the Great Recession.

However, the long-term growth of the upper-middle class, adjusting for inflation, actually accelerated during the 2010s. I was too busy changing diapers to notice. America’s elite inhaled millions more Generation X and Millennials, mainly born into middle-class families. It is now 7% of the U.S. population or twenty-three million adults 25 and over. That’s the same size as the state of Florida population or the seating capacity of 353 large-sized NFL stadiums!

Instead of the mythic rags-to-riches journey the media still loves to highlight, especially with immigrants, this journey never happens. The most recent longitudinal studies tracking class mobility in real-time (with a fixed cohort) indicate that only 6% of Americans born into the bottom income quintile make it to the top quintile (Source: Getting Ahead Or Losing Ground: Economic Mobility in America, 2006, p. 19 Figure 5, Brookings Institution).

The vast majority of the inter-class social mobility in the last half-century appears to have been from the middle-class to the upper-middle-class. As you’re reading this, like me, you can probably list off a bunch of relatives who experienced this dramatic journey, maybe even yourself — climbing from the middle to the upper-middle-class sounds like a less cinematic American dream but a good outcome., correct?

______________________________________________

Why should this exponential growth in the upper-middle-class concern us as a nation?

There are three big reasons, but they are probably not the only ones. 1) The elite has become a functionally endogenous social world in everyday life. Members don’t have to interact with ordinary Americans much at all. They are large enough to develop internal schisms operating at a large scale. 2) Most venture capital funding any innovation focuses on servicing the elite at the expense of social cohesion and public infrastructure investments. 3) This elite shares a core value of consumer hyper-individualism, making them more distracted with trading up to seek distinction than any other elite group in history from the social forces influencing them.

The Inward-Focused Elite — the class stratification of American neighborhoods and zip codes allows most elites to spend their free time mainly in the company of similarly privileged adults. They also work in companies primarily composed of similar elites (i.e., not just the executives). They can hang out in coffee-house third-places full of the similarly privileged. Today, the American elite is so vast that it has developed multiple internal schisms, not all overtly political. Yet, what the Whole Foods elites of the 2000s made me realize at the time was that a large macro-schism was emerging within the American elite. It was dividing the media. It was dividing elite zip codes, even neighborhoods. The schism is between a) ‘left-leaning’ elites favoring individualist techno-modernism instead of social tradition and b) ‘right-leaning’ elites trying to return to an imagined patriarchal past of strict gender roles, limited class mobility for non-whites, even white supremacy. The first group anchored itself in an optimistic future free from the constraints of tradition. The second group arrived in an imagined past, a nervous reaction to multi-factorial social change they find offensive. And in the middle are millions left undecided and confused by both of these divergent perspectives on which way we should be looking: to a hyper-individualist future or a neo-communitarian past. The ‘elite’ is now so enormous that it is more than capable and highly likely to fight internal battles to control our significant institutions; and deploy less ambitious elites and, more importantly, the broader population as mere pawns in intra-elite power struggles. It was far easier for this elite group to get along when it was a minuscule proportion of the population and when 99% of Americans didn’t fit into it. It is the HGTV class. And it’s enormous!

Innovation for Elites by Elites– Elites represent a large audience that consumes more per capita than other SES groups. It is not surprising that most venture capital-funded innovation aims at products and services with these folks as the initial core audience. I don’t see anyone investing in fintech solutions for the unbanked or appliances for use in housing projects where the goal is minimal electricity usage. In consumer products, the innovation audience is usually the same elite subworld as the founder, and if it takes off, it spreads to the middle classes through price reductions. Looking at the Top 10 2021 unicorns, we see that the majority are services most valuable to well-capitalized elites — Instacart, Stripe for small business owners, SpaceX, Canva, and Databricks. In consumer-packaged goods, almost all the funding goes to premium-priced innovations that re-frame existing offerings as inferior in quality (to some audiences). Elite concerns with quality of life, finance/wealth management, and techno-futurism best explain the underlying, non-financial motives for the narrow concentration of funding into IT, finance, healthcare, and consumer products (Source: CB Insights. These cultural domains attract the imagination of elites who have the luxury to contemplate and imagine alternative or ‘better’ futures for themselves (and for others who do not do the initial imagining). This is another reason why elites talk incessantly in business about ‘visioning’ and ‘vision-setting.’ This is a class of people freed of any survival-related issues at all, able to live, like the aristocrats of yore, inside their imaginations and to make those imaginings real (e.g., through innovation). There is no evil intent per se, just an unusually privileged set of base conditions for this degree of future-leaning imagination to become a lifestyle for 23 million adults (see above chart). And to inspire similar thinking among equally well-educated people.

Hyper-individualism Focused on a Personalized Future — David Brooks’ popular ethnography of the upper-middle-class in the late 1990s focused on the seemingly unlimited capacity for Bobos to parse nuances of distinction that they didn’t care at all about even ten years prior. Bobos led a revolution in redefining ‘high quality’ in hundreds of consumer categories starting in the 1990s and continuing through this day. Almost all of these new products reflected emerging values within a portion of the upper-middle-class elite. When I step back, though, most can roll up into very elitist buckets: greater longevity, higher quality of life, elite fitness, thin/skinny body image; the list keeps growing. These newer values or objectives rest on a more fundamental cultural ideology or version of it: hyper-individualism. It continually optimizes life choices for something better, more contemporary, more modern. It is a class ideology anchored in the near future with its sights set way into a future that upper-middle-class people intend to get better and better. Hyper-individualism is not about actually being unique or acting solipsistically. It’s about optimizing and refreshing/updating choices that have just become habits as much as you can until you run out of energy or time. And we all do.

Low Trust in Authorities/Institutions - This long-term trend in the U.S. appears to be intensified among educated elites (though I wish someone would study this more rigorously to confirm it). Those who work close to the owners and leaders of major private and public institutions (i.e. the upper-middle-class elite described here) have the most access to the backstage reality of how institutions function (which does not inspire confidence in many cases). If you are post-grad educated but not leading anything, you will most likely be hyper-critical of the institutions you work for /interact with. You probably think you are more than capable of doing it better. Want a typical example? Many upper-middle-class corporate managers scoff at how the local PTA or public schools communicate and organize events. The professional communicators are NOT impressed.

So, what are the social questions raised by America’s exploding upper-middle-class elite (again, excluding the 1%)?

I do not think it is harmless that a society develops a large elite group this vastly more educated and wealthy than the majority it lives near but with whom it does not interact in any meaningful way. An elite living among Americans but only with transactional monetary relations to the broader public. An elite whose consciousness lies anchored in a personalized, optimized future state and how to get there.

The questions this group raises include, but are not at all limited to, the following:

How do we reconnect elites to ordinary Americans whom they almost never meet?

What constraints on individual freedom need to emerge in the media and finance spheres to prevent toxic misuses of individual freedom?

What forms of new, inclusive community can be created to keep the elite in check?

How do we defend against elite misuse of populism to fight intra-elite battles?

How do we shrink the elite to strengthen the majority?

How does America avoid a neo-nationalist (and likely tyrannical) solution to intra-elite conflict between the old and future order of things?

Oh! Click the banner to buy my latest book for the social critic in your family!

December 11, 2024

Episode 13 - Focus NOT on the Family

To understand how the American family shriveled as the free-range individual took off, we must know how the romantic couple conquered household formation (with or without marriage). Romance is the apotheosis of individualistic household formation, as an act of freely choosing individuals unencumbered by traditional family concerns.

In this episode, I r…

December 7, 2024

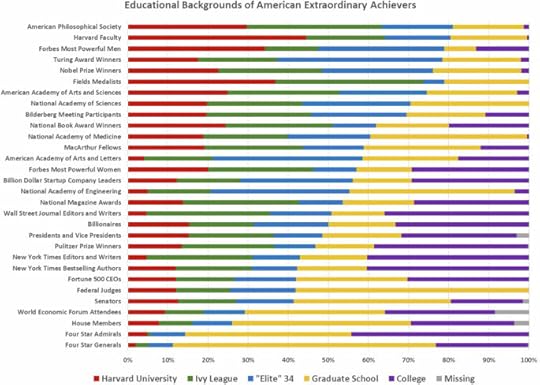

Is There Still a Harvard Effect?

I remember the first and last time I attended a local Harvard Club event when I lived in Seattle. It was the Seattle club’s annual alumni interviewing information session, held on a rainy November evening at a lakeside estate in Yarrow Point (a Lake Washington neighborhood for the ultra-rich).

Let me be clear. I have no issue socializing with wealthy Americans. I’m not a Bolshevik. In fact, as a social scientist, I find their attempts to be “normal” and non-elitist highly amusing to observe. Everywhere else I have lived and studied on planet Earth, the rich are obnoxiously rich, don’t give a sh*t that you’re offended, and want you to never forget their wealth (e.g., India’s Ambani family). I understand the basics of dealing with these folks (i.e., don’t gasp when they cursorily mention some obscene service expenditure you would never pay for - like full-time, on-site housekeeping staff). I went to school with these folks from grade 7 through college. They’re just humans with far too much money. Again, not a Bolshevik.

I first recognized that most club members attending knew each other well. And the host never once greeted me after I signed in. I never even met him. Or I did, and I didn’t realize he was the host (!). It was like his home had been turned into a business convention ballroom where the gatekeeping had been done elsewhere. As I circulated awkwardly, I noticed the attendees were almost all in finance or hi-tech (shocker). They did not know what to talk to me about when I introduced myself as an anthropologist doing market research.

Shouldn’t you be a professor with an ‘important’ book plugged on NPR? They probably wondered to themselves. Have you achieved enough, James?

No one was overtly rude or dismissive that night. It’s the West Coast, so folks don’t slam judgmental statements at you like a snarky New York City party. It was simply an evening of polite non-connection. I was not high-achieving enough for these folks, even with my dusty PhD.

I mean, doesn’t everyone have a PhD, James?

I guess. 2.5 million PhD holders live in the U.S., and I once worked in an office with 12 of them. PSA - Don’t ever work in such a place, trust me. PhDs are anti-social and need lots of territory, like the male Andean Puma (i.e., 100-200 square miles). A Tesla Gigafactory is not large enough to contain 12 PhDs without growling and biting.

After the perfunctory presentation on how to help with alumni interviewing, I wrote down my name and contact info so that I could volunteer my time. I had low expectations. And no one followed up. Um, do I need to sign quicker next time? Is this too a competition?

Indifference was the ‘vibe’ I got that evening. Who are you, again? Oh, the anthropologist without a real job in anthropology. Sad. Should have gone to business school, my man.

WTF? Weren’t we all Harvard College graduates? And why are we all here measuring the length of our career penises in front of each other? Aren’t we supposed to be singing Fair Harvard and telling tall tales of eating 2 AM bowls of Chop Suey while under the influence?

Argh! Ivy League people are infuriatingly competitive sh*theads.

As I left, I congratulated myself for marrying outside the tribe.

I met a few College grads that night, but as I discovered in person, most Harvard Club members are only members because they have Harvard graduate degrees…mostly from Harvard Business School. Sigh.

I had been looking for the wrong club that evening, the one that wants Harvard College grads to interview applicants to Harvard College!! Outrageously elitist, I know! How dare I presume to have superior judgment to a mere HBS grad!

That evening clarified that the local Harvard Club was not really for all Harvard alumni. It was a club for the Seattle 1%, who happened to be Harvard alumni and mostly held MBAs. I'm sure many of these folks were nouveau riche, but the primal tribe was still class - class privilege linked to specific ultra-high-earning professions (or entrepreneurship). This party was chock full of the hard-charging, ultra-meritocratic elite, which David Brooks laments for ruining America in a recent Atlantic piece. (Brooks is the ‘low achieving’ NY Times journalist who graduated from the ‘humble and nonselective ’ University of Chicago)

Please don’t despair at how plebeian the Harvard Club has become; there is still a splash of the multi-generationally wealthy. You’ll always find one (with or without an MBA) nursing a Scotch in a chair, wondering what it’s like to “work” because you’ll lose your house if you don’t. What does that feel like?

That bizarre cocktail party of plate-mail-wearing W-2 Crusaders was not the first time I realized that my Harvard degree would not matter much for networking or that stumbling on a Harvard peer would not lead to anything remotely approaching the fist-bumpish reaction fellow “Badgers” from the University of Wisconsin give to each other.

Years earlier, my dissertation advisor (a Sarah Lawrence grad) could not have cared less about my Ivy League degree, OR she incorrectly assumed I was from the Harvard-educated 1% (a group she openly disdained as a left-wing anthropologist).

The more successful and typically employed you are as a Harvard College grad, the more likely you’re working somewhere where nowhere gives two sh*ts about your elite degree. The last place anyone cares about your Ivy League college degree is in fields like academia, management consulting, federal employment, Congress, philanthropy, or finance. These fields are awash in Ivy League degree holders, especially Congress, finance, and consulting.

As college attendance has exploded in the U.S., educational pedigree has ironically become increasingly meaningless among the very professional elite the Ivy League degree disproportionately sends its graduates to join. The Ivy League tribe itself is simply too vast now to create tight bonds of social trust. 500,000 living people have one of these degrees.

And we stand divided by far more critical identity markers. No, I’m not talking about race or gender. Sorry. I’m talking about the superior cultural power of professional tribes that transect alumni communities into a miniature version of the American caste system (i.e., a system of hierarchically arranged labor groups).

The triumph of professional identities in modern life has made elite alumni networking more or less pointless or simply an initial filtering device. Post-pedigree professional networking is vastly more powerful. This has certainly been true in my career. Again and again.

I suspect this is, in part, a logic of evolutionary human biology, in which humans gravitate to the most tightly aligned tribe they can muster in their social world. We really do prefer parish-sized social groups of 100-150…large enough to prevent incest but small enough so that we can know a ton about everyone.

As the upper-middle class has grown in proportion to the general population in the last fifty years, there are now simply too many ultra-highly educated people in close social proximity. And, if we are one of those professionals, we are more likely than ever to socialize entirely within this bizarre world of un-American Americans, chock full of Ivy League degrees.

So, our primitive human brains seek to find a smaller tribe. And our profession works better in terms of local social networks.

I can not establish it empirically, but the value of “Harvard” or “Yale” when networking within professions that don’t tend to have many of these punks is the most powerful. I’ve often experienced this power because I work in a non-elite industry vertical.

In the consumer packaged goods industry, for example, when asked where I went to school, the reaction, to my surprise, is usually flattering.

I found something eerily similar with regard to the PhD occasionally placed after my name. In my current industry, most non-Ivy grads are impressed and willing to call me “Dr.” until I ‘permit’ them not to do this. In academia or consulting, no one calls anyone else “Dr. Blah Blah.” Ever. Not anymore. In elite professions, harking back to prior educational achievements is gauche.

And here’s why.

Pedigree-based networking can NOT have much value in an urban culture focused on individual achievement in work and love. It really shouldn’t. You are only as powerful a social force as your most recent, significant achievement.

Always. Achieve. More.

Or face certain social death.

My expectation that rainy November evening at Yarrow Point was painfully antiquated because it rested on believing that my past should influence my access to current social resources.

Nope.

Only my most recent massive professional achievement. And I was languishing at the time. It was clear in my narrative and tone.

I have found that an Ivy League degree consistently impresses those in the general college-educated population—even the MAGA voter. It is a rare and well-cultivated national symbol pointing to someone likely to achieve a lot. Even, as in my case, it comes in an awkwardly wrapped package requiring loads of therapy.

The powerof this symbol can only be felt outside of the tribe itself, in the general population. Not as a networking tool but as a personal branding “badge.” You won’t get a phone call because you went to Harvard. You may do better on that call because Harvard and all the elite U.S. colleges tend to filter for a rarified bunch with better language skills than the average bloke. We tend to communicate very well in writing, verbally, or both.

But there’s something else.

Ivy League, especially Harvard College graduates, are far more likely than the average peer to achieve extraordinary things marked off by most of us as culturally significant. This is the conclusion of a large national study published in Nature.

The extreme liberal arts luminaries of America tend to come from this tiny group of elite schools, not a typical college or university. However, if you’re a four-star general, no one cares that you went to Harvard or Princeton.

But, remember that this study is measuring over-representation in class of achievement.

This study does not prove that going to an Ivy League school guarantees extraordinary success. My network of Harvard friends from the Class of 1994 is a good case in point. I have classmates who have lost their lives to boring corporate careers that are of minimal interest to them. I also have U.S. District attorneys, voter registration activists, and published authors.

Yes, the definition of extraordinary achievement used in the study above is awfully narrow. But extreme behavior tends to reveal hidden dynamics of power and access in complex societies. This is an old social science technique. Measuring the margins.

It’s still debatable how much the Ivy League filters for people more likely to be high achievers or transform young adults into high achievers. I lean toward the filtering hypothesis myself.

Here’s a stray conclusion from the Nature study that I find quite revealing:

…the incredible influence of Harvard University—overrepresented among remarkable achievers by up to 80 times in a pattern one might call the Harvard Effect—is documented quantitatively here for the first time. Perhaps attending Harvard is not only a reflection of inputs, a gateway to critical educational and social experiences, or access to invaluable alumni networks, but also a more subtle treatment effect that increases one’s ambitions or expectations.1

It’s almost impossible to quantitatively analyze the latter hypothesis. Still, I strongly suspect it is at play because I’ve seen it present in the careers of my Harvard roommates and conspicuously absent in the careers of many of my business colleagues.

On more than one occasion, I’ve counseled someone informally, including a few paid clients, that “Your problem, [INSERT NAME], is that you lack Ivy League ego confidence.”

I’m not talking about cockiness, over-confidence, or delusional egoism. That is way too common among all men to be helpful here.

I mean a baseline confidence that makes you emotionally invincible against random idiots who want to challenge your contributions or potential in your chosen field.

Nope. You just remain quiet and smile internally at their folly. You may even decide they are correct, learn something, and improve! This would make them wrong for denying your potential.

Ivy Leaguers tend not to let others deny their potential. Ever.

As I’ve journeyed through the business world for the past 25 years, I’ve worked for both post-grad-educated professionals at huge multinationals and less well-educated business amateurs, acting as startup founders. The farther I get away from the professional classes, the more influential the “Harvard effect.” I’m referring specifically to the “ego confidence” effect.

People respond to unusual social confidence.

I’ve even worked for an owner who routinely mocked the Ivy League yet frequently hired its graduates (!) and promoted me five times in a row due to my “incredible potential.” (I just had to learn to control my mouth in the hair-trigger conversational business world.) Hmmm…