Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 88

May 4, 2017

Missing you

Dear one, I left love notes

for you everywhere today --

tucked into the petals

of the tulip magnolia

encoded in the braille

of black willow bark,

hidden in the patterns of rain

on your windshield

-- but you didn't notice.

My missives remain unread.

Your despair renders me

invisible. You forget

I'm right here. How

can I balm your sorrows?

If only you could hear me

in the ring of your phone.

Feel my fingers

twined with yours, my kiss

on the tender place

in the middle of your palm.

What if everything in our lives were a love note from God, but most of us are too distracted most of the time -- by life, by our to-do lists, by our griefs -- to experience ordinary things like blooming trees or rainfall as expressions of love? That's the question that sparked this poem.

Lately I've been thinking of laying tefillin as "holding hands with God." The closing lines of this poem come from that image and that experience of wrapping my fingers with the leather straps and feeling as though the Holy One of Blessing were holding my hand.

This is part of the series I've been thinking of as God's responses to my Texts to the Holy poems. Others in the series: Because, Always, God says yes.

May 2, 2017

How to embrace living in the unknown, in The Wisdom Daily

...When I accept that I can’t wholly know what my future will hold, I open myself to possibility. There are things I hope will happen. There are things I hope won’t happen. But I affirm that I don’t actually know what will be, and that there is a gift for me in the not-knowing. Because I don’t know, I can hold my imagined futures lightly. I can cultivate openness to learning from whatever unfolds. I can cultivate the bravery I need to keep moving forward, even when I don’t always know for certain where I am headed or how I will get there....

That's from my latest essay for The Wisdom Daily: How to embrace living in the unknown. I hope you'll click through and read the whole thing.

May 1, 2017

Because

ואהבת לרעך כמוך: אני הוי׳׳ה

Love your other as yourself: I am God. - Lev. 19:18

Because I am God

I ache

to give sweetness

my cup spills over

every time you need

or hurt

Because I carry

your heart

in mine

Because you carry my heart

in yours

you ache too

in the yearning

between us

is holiness

This week's Torah portion, Kedoshim, is at the heart of the Torah: the middle portion of the middle book of the five. And in the very heart of the heart of the Torah is the verse cited at the top of this poem -- the injunction to love one's neighbor, one's other, as oneself.

This year I found myself thinking about the juxtaposition of that verse with the words "I am God." What is Torah trying to tell us -- what's the connection between God being God, and us being called to love others? I thought about the teaching from Talmud (Pesachim 118) about how God yearns to give us blessing. I thought about how when we love one another, we feel (and want to balm) one another's losses. I thought about how it is the nature of God to ache to give to us, and how we are made in the divine image and therefore we partake in that same aching. And I thought of the word kadosh, "holy" -- a root which appears repeatedly in this week's Torah portion, and also appears in the word kiddushin, the sanctified relationship between two beloveds.

This poem arose out of all of those. It's not part of my Texts to the Holy series (it's spoken in the Divine voice to us, rather than in our voice to the beloved or Beloved) but is part of the newer series I've been writing lately, along with Always and God says yes.

April 28, 2017

Healing and second chances

[image error]A few days ago we entered into the new month of Iyar. Here's my favorite teaching about the month of Iyar: its name is an acronym for something beautiful. Torah teaches that after the children of Israel crossed through the Sea of Reeds and reached the far shore, they sang and danced -- and then, once they began their journey in the wilderness, they became afraid. What if there were no potable water for them to drink? What if there weren't enough to nourish them in life's journey?

So God instructed Moshe to throw a piece of wood into a stagnant pond, and the water became sweet. And then God offered one of Torah's most beautiful reassurances, saying "I am YHVH your healer." That's the phrase we can see hidden in the name of the month Iyar: אני יה רפאך / I am God, your healer.

In the words of my friend and teacher Rabbi Yael Levy of A Way In:

Iyar is an acronym for this promise the Divine Mystery has made to us: I am your healer. On life’s journeys you will face the seas of struggle, celebration, fear and joy, and whatever comes, I am there to heal and guide you. (Exodus 15:26)

She continues:

Iyar is a month of second chances because the full moon of Iyar provides the opportunity to make up for something that has been missed. During Temple times, it was considered essential for a person’s spiritual and material wellbeing to compete a sacrificial offering for Passover. If circumstances kept someone from someone from making this offering, he/she was given another opportunity to do so on the 15th day of the month of Iyar.

Iyar says it is never too late -- no matter what situation we find ourselves in, no matter how far away we have traveled from our intentions or goals, it is possible to find our way back.

Every life contains missteps and missed opportunities -- times when we look back and realize we wish we'd chosen differently. If only I had reached out to that person then, instead of staying silent. If only I had walked through that door, instead of staying outside. If only I had said "I love you" while I still could. If only, if only.

Part of what it means to me to say that God is our healer is to say that God accompanies us into our second chances. I don't have a time turner; I can't actually go back in time to undo my mistakes, so that I could do then what I wish now that I had done. But Rabbi Levy points out that just as our ancestors were given the opportunity to offer the Pesach sacrifice late, we too can find opportunities to make up for where we missed the mark... and I think that's one way that God can help us to find healing.

Illness and healing are major themes in this week's Torah portion, Tazria-Metzora. Torah's ancient paradigm of tamei and tahor, impure and pure -- or charged-up with the energy of life and death, and absent that psycho-spiritual "electricity" -- may not speak to us. But part of what I relearn from this Torah portion each year is that when one is sick, whether physically or emotionally or spiritually, one may feel exiled from the community. Cut off and isolated. "Outside the camp" in an existential sense: alone even when surrounded by other human beings.

And in those times God comes to us and reminds us אני יה רפאך -- I am God, your healer. I am the One Who is with you in sickness and in health, the One Who accompanies you even when you feel most existentially alone.

When we are sick and feel isolated, the One Who Accompanies is with us. And when we are sick at heart because of the places where we missed the mark, the One Who Accompanies is with us too. May this month of Iyar be a time when our second chances gleam bright before us, so we can find healing in making amends, and making new choices, and remembering that -- as Rabbi Levy teaches -- no matter how far we've strayed from where we meant to be, it's never too late to find our way back.

This is the d'var Torah I offered at CBI this morning. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

Coming to Maine!

The month of May is almost upon us, and with it comes a weekend I've been looking forward to for some time: an opportunity to visit Congregation Bet Ha'Am in Portland, Maine with Rabbi David Evan Markus! We're honored to be this year's Bernstein Scholars-in-Residence there. (Previous years' scholars have included Dr. Nehemia Polen, Rabbi Lawrence Kushner, and Rabbi Art Green.)

Over the course of our weekend, we'll be co-leading a Kabbalat Shabbat service, offering Shabbat morning Torah study, offering a Shabbat evening se'udah shlishit ("third meal") and havdalah program with teaching and poetry, and sharing some teaching with their community Hebrew school on Sunday morning. Through song, text, teaching, and experience we'll offer an introduction to Jewish Renewal.

Here's what they've shared about our visit on their website:

Congregation Bet Ha'am, through the Rosalyne S. & Sumner T. Bernstein Scholar-in-Residence Fund, is proud to welcome this year’s Bernstein Scholars-in-Residence, 'The Velveteen Rabbi" Rachel Barenblat and Rabbi David Markus, co-chairs of ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal. Mark your calendars and plan to join us for the weekend of May 5-7, 2017.

The weekend marks the halfway point between Passover and Shavuot, exactly halfway between liberation and revelation. Here, the Torah teaches us “Love your neighbor as yourself.” Activities and discussions will focus on the themes of love, community, and holiness through various practical and spiritual lenses. We’ll look at how Jewish Renewal can use themes and motifs to deepen the spiritual experience of public prayer services timed to the Torah cycle and the spiritual flow of the year, how mitzvot are intertwined with ritual, and the support of Jewish community in modern times.

Friday, May 5, 7:30 PM - Kabbalat Shabbat Evening Service: Holiness, Love, and Community - Loving your neighbor in modern times.

Saturday, May 6 9:00 AM - Torah Study: The spiritual and practical of community and renewal.

6:00 PM - Potluck Seudat Shlishit and Havdalah: Havdalah Service with a program on Illness and Healing.

Sunday, May 7 10:30 AM - Adult and Children’s Workshop Mitzvah and Mysticism - Holy Doing and Holy Being.

All are welcome!

Please contact Benjamin Gorelick in the Bet Ha'am office at 879-0028 or benjamin@bethaam.org for more information about this exciting weekend.

If you're in or near Portland Maine, we hope to see you there next weekend.

[image error]April 26, 2017

The Book of Joy

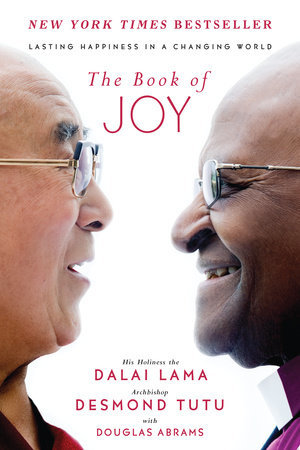

When a friend told me that she was reading a series of dialogues between His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu on joy, my first thought was "I need to read that too." Their dialogues are published in a book attributed to the two luminaries along with Douglas Abrams, called The Book of Joy.

When a friend told me that she was reading a series of dialogues between His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu on joy, my first thought was "I need to read that too." Their dialogues are published in a book attributed to the two luminaries along with Douglas Abrams, called The Book of Joy.

Here's the first place in the book that drew forth my impulse to make marginal markings. This is the Archbishop speaking:

Discovering more joy does not, I'm sorry to say, save us from the inevitability of hardship and heartbreak. In fact, we may cry more easily, but we will laugh more easily, too. Perhaps we are just more alive. Yet as we discover more joy, we can face suffering in a way that ennobles rather than embitters. We have hardship without becoming hard. We have heartbreak without being broken.

We may cry more easily, but we will laugh more easily, too -- that feels right to me. Joy is not the antithesis of sorrow. It doesn't cancel sorrow out, or make one less prone to the sorrows that come with human life. But joy can help us face our sorrows in a different way.

Abrams seizes on this, and brings it back to the Archbishop: "The joy that you are talking about," he says, "is not just a feeling. It’s not something that just comes and goes. It’s something much more profound. And it sounds like what you’re saying is that joy is a way of approaching the world." The Archbishop agrees, and adds that as far as he is concerned, our greatest joy arises when we seek to do good for others.

Coming from anyone else, that might sound insincere, but from Desmond Tutu I am inclined to believe it. Reading his words made me aware that I fear I don't spend enough time seeking to do good for others. But then I realized that he could be speaking not only about vocation or community service, but also on a more intimate scale about trying to do good for people I love. Doing something to brighten the day of someone I love brings me intense joy. (Maybe the real work is figuring out how to broaden the sphere of those whom I love.)

The Archbishop also says some things about hope that resonate deeply for me:

"Hope," the Archbishop said, "is quite different from optimism, which is more superficial and liable to become pessimism when the circumstances change. Hope is something much deeper..."

"I say to people that I'm not an optimist, because that, in a sense is something that depends on feelings more than the actual reality. We feel optimistic, or we feel pessimistic. Now, hope is different in that it is based not in the ephemerality of feelings but on the firm ground of conviction. I believe with a steadfast faith that there can never be a situation that is utterly, totally hopeless. Hope is deeper and very, very close to unshakable..."

"Despair can come from deep grief, but it can also be a defense against the risks of bitter disappointment and shattering heartbreak. Resignation and cynicism are easier, more self-soothing postures that do not require the raw vulnerability and tragic risk of hope. To choose hope is to step firmly forward into the howling wind, baring one's chest to the elements, knowing that, in time, the storm will pass."

I love his point that optimism depends on feelings, and it's the nature of feelings to be malleable. Often I know that the way I feel isn't necessarily correlated with how things "actually are" -- intellectually I can see that things aren't so bad, but emotionally I feel as though they are. (Or the other way around.) If my optimism depends on feeling good about the situation at hand, it will necessarily falter sometimes.

Hope, for the Archbishop, is something different. Hope is a choice, a way of being in the world. Hope is an affirmation that whatever challenges, or grief, or sorrow may be arising will pass. Hope says: there is more to life than this, even if we can't see that right now. In a sense, it requires a leap of faith. It asks us to operate on the assumption that there is more to life than whatever we are experiencing right now.

Abrams writes:

We try so hard to separate joy and sorrow into their own boxes, but the Archbishop and the Dalai Lama tell us that they are inevitably fastened together. Neither advocate the kind of fleeting happiness, often called hedonic happiness, that requires only positive states and banishes feelings like sadness to emotional exile. The kind of happiness that they describe is often called eudemonic happiness and is characterized by self-understanding, meaning, growth, and acceptance, including life’s inevitable suffering, sadness, and grief...

"We are meant to live in joy," the Archbishop explained. "This does not mean that life will be easy or painless. It means that we can turn our faces to the wind and accept that this is the storm we must pass through. We cannot succeed by denying what exists. The acceptance of reality is the only place from which change can begin."

I'm struck by the Archbishop's assertion that we are meant to live in joy -- and that this doesn't mean that life can be, or even should be, devoid of pain. Joy and sorrow are so often intertwined: at the happy occasion when one remembers a loved one who has died, at the celebration of a joyous milestone when a loved one is struggling. We shatter a glass at every Jewish wedding to remind us that even in our moments of joy there is brokenness. Authentic spiritual life calls us to hold this disjunction all the time.

Archbishop Tutu is right that authentic spiritual life also calls us to begin by recognizing what is, and sometimes what is is painful. But we can hold that painful reality loosely, alongside awareness of the gifts we receive from loving others and aspiring to sweeten their circumstance. As the Archbishop also notes, when we seek to do good for others, we open ourselves to some of life's deepest joy. And that's a joy that is rooted not in what we have, but in what we give away -- in the love and caring that comes through us. And because it comes through us, rather than from us, it has no limits.

The Psalmist wrote, "Weeping may tarry for the night, but joy comes in the morning." The "night" in question may be long. It may be personal, or national, or global. But we can live in hope that morning will come and will bring joy, even if we don't know what that will look like, even if we don't know when or how that will be.

Related:

Joy, 2009

April 21, 2017

Always

When I say I love you

I mean always: when you greet

the day with exultation

and when you wake with tears

when you shine like the skies

and when you're clenched

in despair's grip,

every drop of joy wrung out.

Sometimes you're bare branches,

then chartreuse life bursts free.

Do you imagine I'm with you

only in the springtime?

You are precious to me

when you feel strong

and when you feel broken

and when you can't feel at all.

I'd give you a talisman

to carry in your wallet, a string

to tie around your finger

but I know you:

you'll stop wearing it

or stop remembering what it means.

It means always, even

when you can't see me.

When you push me away

because hope hurts too much.

Even then, what I feel for you

eclipses the light of creation.

I'm working on a new series of poems.

The Texts to the Holy poems (my next collection, coming out from Ben Yehuda later this year ) are in my own voice, spoken to the Beloved (or beloved). These poems are in response -- love poems that you might read as spoken by the Beloved to us.

(Related: God says yes.)

April 20, 2017

Learning to Walk in the Dark

If you are in the middle of your life, maybe some of your dreams of God have died hard under the weight of your experience. You have knocked on doors that have not opened. You have asked for bread and been given a stone. The job that once defined you has lost its meaning; the relationships that once sustained you have changed or come to their natural ends. It is time to reinvent everything from your work life to your love life to your life with God -- only how are you supposed to do that exactly, and where will the wisdom come from? Not from a weekend workshop. It may be time for a walk in the dark.

-- Barbara Brown Taylor

When we were in Tuscaloosa, my friend and colleague Reverend Rick Spalding mentioned to me that he was reading Barbara Brown Taylor's Learning to Walk in the Dark. "That sounds like a book I need to read," I said. Not long thereafter, I found his copy in my mailbox, waiting for me to read it.

And oh, wow, did I need to read this book. The copy I was reading wasn't mine, so I didn't give in to the temptation to underline and highlight -- but if I had, it would be marked up everywhere, because so much of what Barbara Brown Taylor writes here resonates with me. Like this:

Even when you cannot see where you are going and no one answers when you call, this is not sufficient proof that you are alone. There is a divine presence that transcends all your ideas about it, along with your language for calling it to your aid... but darkness is not dark to God; the night is as bright as the day.

Sometimes we feel that God is agonizingly absent from our lives, but this is a matter of epistemology, not ontology -- a matter of how we experience the world around us, not a genuine indicator of how that world actually is. This is a core tenet of my theology. I felt a happy spark of recognition, reading it in Brown Taylor's words.

Reading her words about cherishing darkness, I found myself thinking about the wisdom of my seven year old son. As I rejoice that the days are getting longer, he gets sad: "but Mom, that means I won't be able to see the constellations anymore, or the Evening Planet!" He means Venus, which he resolutely refuses to call the evening star because, he notes, it is not a star. His bedtime is 8pm, which means that in summer he doesn't see the stars most nights at all. I am grateful to him for reminding me that there is beauty in the dark... and grateful to Brown Taylor for exploring the valances of darkness so deeply.

Barbara Brown Taylor is clear that in our antipathy to darkness, we also manifest a discomfort with everything that isn't simple and solar and bright... but a full human life contains both light and darkness, both literally and metaphorically, and that's as it should be. She writes:

The way most people talk about darkness, you would think that it came from a whole different deity, but no. To be human is to live by sunlight and moonlight, with anxiety and delight, admitting limits and transcending them, falling down and rising up. To want a life with only half of these things in it is to want half a life, shutting the other half away where it will not interfere with one's bright fantasies of the way things ought to be.

[W]hen we run from darkness, how much do we really know about what we are running from? If we turn away from darkness on principle, doing everything we can to avoid it because there is simply no telling what it contains, isn't there a chance that what we are running from is God?

Isn't there a chance that what we are running from is God? As a spiritual director, I adore that question. I want to return to it often.

On waking in the night, she writes:

What if I could learn to trust my feelings instead of asking to be delivered from them? What if I could follow one of my great fears all the way to the edge of the abyss, take a breath, and keep going? Isn't there a chance of being surprised by what happens next? Better than that, what if I could learn how to stay in the present instead of letting my anxieties run on fast-forward?

What if I could learn to stay in the present: yes, that's it exactly.

She writes at some length about Miriam Greenspan's Healing Through the Dark Emotions. In this passage, she's describing Greenspan's story of her first child dying two months after he was born:

Like any parent struck down by such loss, she woke up every morning in the salt sea of grief and went to bed in it every night, doing her best to keep her head above water in between. This went on for weeks, then months, during which time she could not help but notice how uncomfortable her grief was making those around her, especially when it did not dry up on schedule...

[She explored] the idea that emotions such as grief, fear, and despair have gained a reputation as "the dark emotions" not because they are noxious or abnormal but because Western culture keeps them shuttered in the dark[.]

It is easy to imagine (or to hope) that grief has a schedule and will go away on a set timetable. It does not, and it will not. But that doesn't make grief or sadness a bad thing: sometimes they are the only reasonable reaction to the realities in front of us. And I believe wholly that the only way through them is through them -- not pretending them away.

This puts me in mind of Jay Michaelson's writings about sadness. (I posted about that a while back -- see my review of his book The Gate of Tears.) We get ourselves into trouble when we resist our sadness and our grief, or when we imagine that we are supposed to be able to sidestep them, or when we imagine that they will go away on schedule.

Brown Taylor cites Greenspan here also on spiritual bypassing -- "using religion to dodge the dark emotions instead of letting it lead us to embrace those dark angels as the best, most demanding spiritual teachers we may ever know....It is the inability to bear dark emotions that causes many of our most significant problems, in other words, and not the emotions themselves." Yes, yes, and yes. (A lot of my reactions to this book boil down to yes!)

For those of us who cherish religious practice, there is real risk of spiritual bypassing -- using our religious rituals or practices to distract us from what we're feeling, or to paper over what we're feeling. But authentic spiritual life calls us to do something different: to bring what we're feeling into our religious practice, even when what we're feeling hurts. (I've written about this before: see Sitting with sadness in the sukkah, 2015.)

There's so much else in this book that speaks to me. Like this brief passage on Jacob's night-time wrestle with the angel that earned him the new name Yisrael, God-wrestler:

Who would stick around to wrestle a dark angel all night long if there were any chance of escape? The only answer I can think of is this: someone in deep need of blessing; someone willing to limp forever for the blessing that follows the wound.

Or this:

"Since becoming blind, I have paid more attention to a thousand things," Lusseyran wrote. One of his greatest discoveries was how the light he saw changed with his inner condition. When he was sad or afraid, the light decreased at once. Sometimes it went out altogether, leaving him deeply and truly blind. When he was joyful and attentive, it returned as strong as ever. He learned very quickly that the best way to see the inner light and remain in its presence was to love.

The best way to see the inner light and remain in its presence was to love: yes, that feels right to me. I know that in my own darkest times, my own times when God's presence has felt so occluded as to seem absent altogether, my best way to open myself again to that presence is to cultivate love.

I don't want to minimize the dark night of the soul, and neither does she:

[T]he reality that troubles the soul most is the apparent absence of God. If God is light, then God is gone. There is no soft glowing space of safety in this dark night. There is no comforting sound coming out of it, reassuring the soul that all will be well. Even if comforting friends come around to see how you are doing, they are about as much help as the friends who visited Job on his ash heap. There is an impenetrability to the darkness that isolates the soul inside it. For good or ill, no one can do your work for you while you are in this dark place. It has your name all over it, and the only way out is through.

(She immediately distinguishes between the dark night of the soul as a spiritual condition, and depression as a medical condition, and I'm grateful that she does. Having experienced both, I can attest to the fact that they are qualitatively entirely different, even though some of their outward markers -- grief and tears chief among them -- are the same.)

In the end, what the darkness asks of us -- she says -- is simple presence:

When we can no longer see the path we are on, when we can no longer read the maps we have brought with us or sense anything in the dark that might tell us where we are, then and only then are we vulnerable to God's protection. This remains true even when we cannot discern God's presence. The only thing the dark night requires of us is to remain conscious. If we can stay with the moment in which God seems most absent, the night will do the rest.

I would argue that that's what life asks of us in general: our "dark" times, and our "light" ones alike.

Toward the end of the book, she writes about the moon -- which is a quintessential part of the Jewish religious calendar (and even more so the Muslim one), though not the Christian one, most of the time. The moon is a great teacher about the ebbs and flows of spiritual life. She writes:

Sometimes the light is coming, and sometimes it is going. Sometimes the moon is full, and sometimes it is nowhere to be found. There is nothing capricious about this variety since it happens on a regular basis. Is it dark out tonight? Fear not; it will not be dark forever. Is it bright out tonight; enjoy it; it will not be bright forever.

Is it dark out tonight? Fear not: it will not be dark forever. And even though darkness will inevitably return, so will its end. For me, right now, that is a profound theological statement about the return of hope and the hope for a future that is better than what we have known in the past. May it be so.

April 18, 2017

A ritual for the end of Pesach

"Is there something like havdalah for the end of Pesach?"

"Is there something like havdalah for the end of Pesach?"

That question was brought to me a few days ago by my friend and colleague Reverend Rick Spalding.

Reverend Rick has, in the past, expressed to me his "holy envy" of havdalah. (In Krister Stendahl's terms, one feels holy envy for that thing in another tradition which one wishes existed in one's own tradition.) I love that he thought to ask about whether we have a separation ritual for the end of Pesach... and I'm kind of sad that the answer is no.

(This is additionally complicated by the fact that as a people, we don't agree on when the end of Pesach is! Jews in the land of Israel observe seven days. Reform Jews everywhere do likewise. Conservative and Orthodox Jews outside of Israel observe eight days. To the best of my knowledge, the Reconstructionist movement doesn't set official policy on this matter. And Renewal Jews exist everywhere -- in communities of every denominational affiliation and no denominational affiliation -- so it's impossible to generalize.)

But regardless of whether the end of Pesach comes after the seventh day or the eighth day, we don't have a formal ritual for ending the festival. Those of us who remove leaven from our homes during the festival have probably evolved informal rituals for moving the Pesachdik dishes back into storage and the regular dishes back into rotation, or for buying or baking the first loaf of bread after the festival has come to its close. But there's nothing like havdalah to mark the end of festival time.

What we do have is the tradition of counting the Omer, the 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot. In a sense, counting the Omer blurs the boundary at the festival's end. Long after Pesach is over, we're still counting the days until the revelation of Torah at Sinai -- a journey we began at the second seder. The counting stitches the two festivals together, making the end of Pesach less stark. Passover ends, but the Omer continues as each day we turn the internal kaleidoscope to see ourselves through new lenses.

When weather permits, at this time of year, I like to sit outside on my mirpesset and watch the evening sky change. As darkness takes over the sky I make the blessing and count the new day of the Omer. Watching the sky slowly shift from one shade of blue to the next, it's clear to me that the end of a day isn't a binary. We don't go from day to night in a single moment of transition. As our prayer for oncoming evening makes clear, "evening" is a mixture of day and night, constantly shifting.

There's some of that same fuzziness in the end of Pesach. Even once we've moved the regular dishes back into the kitchen, or gone out for that first celebratory pizza after a week of matzah, the festival lingers. It lingers in the counting of the Omer. It lingers in the matzah crumbs we'll be sweeping up for weeks. It lingers in our consciousness, in our hearts and minds, in whatever in us was changed this year by re-encountering our people's core narrative of taking the leap into freedom.

Still, Reverend Rick's question continues to reverberate in me. Havdalah has four elements: wine, fragrant spices, fire, and a blessing for separation. If we were to dream a ritual for the end of Pesach, how would we re-imagine havdalah for this purpose? The one thing that's clear to me is that the ritual would need to be simple and accessible, not requiring additional preparation -- Pesach is so full of extra work that I don't think I could bear to add additional strictures or obligations or ritual items!

Blessing a glass of wine, symbol of joy, is easy. For the fragrant spices, this year, I want a scent of the outdoors -- from my mirpesset I can breathe the sharp scent of new cedar mulch -- to spark my soul's embrace of what is growing and unfolding and new. Instead of the light of a braided havdalah candle, I might hold my hands up to the ever-changing light of the sky. And as a blessing of separation, the new night's Omer count, separating and bridging between what was and what is yet to be.

April 14, 2017

Ready to be changed

This week we're taking a break from the regular cycle of Torah readings. Our special Torah reading for Shabbat Chol Ha-Moed Pesach, the Shabbat that comes in the midst of this festival, returns us to the book of Exodus.

This week we're taking a break from the regular cycle of Torah readings. Our special Torah reading for Shabbat Chol Ha-Moed Pesach, the Shabbat that comes in the midst of this festival, returns us to the book of Exodus.

In this Torah portion, Moshe pleads with God, "Let me behold Your presence!" And God says "Yes! -- and no." God says, "I will make My goodness pass before you, but no one can look upon Me and live." God says, "Let Me protect you in this cleft of a rock, and after I pass by, you can see my afterimage."

This is among the most intense and profound moments in Torah. We could spend hours exploring this text... and instead I have two minutes.

I was talking about that this week with my learning partner -- after all, rabbis keep learning too -- and the question arose: so how long did it take for God to pass by? Probably none of us believe that God has a physical body, so this question is about Moshe's awareness. In Moses-time, maybe it took two minutes. Probably it happened in a flash. An experience -- even a life-changing one -- can unfold in two minutes. But understanding that experience, integrating it into the fullness of our lives, can take a lifetime.

The teacher of my teachers, Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi z"l, said that "theology is the afterthought of the believer. You never have someone coming up with a good theology if he or she didn’t first have an experience." Experience comes first. Our attempts to understand that experience come after.

Understanding can happen in the body, when we feel something viscerally. Or in the mind, or the heart, or the spirit. Often it's one but not the other -- you know how sometimes you know something in your head, but your heart hasn't yet gotten the memo? Experience is easy. Understanding is harder.

Your years at Williams are like that too, filled with experiences that might take you weeks, or months, or a lifetime to fully explore. The thing is, we never know which moment will be the moment when an experience knocks us off our feet and changes us. We have to be open to it whenever it comes.

And that takes me back to Pesach. When it was time to leave slavery, the children of Israel had to go right then. No time to let their bread dough rise, just -- time to go, now, ready or not. One minute they were hemmed-in and trapped, and the next minute they were faced with wide-open possibility.

The haggadah says each of us should see ourselves as though we ourselves had experienced that transformation. Every life is filled with Exodus moments: when everything you thought you understood turns upside-down, when you realize your world is more expansive than you ever knew, when you have to take a leap into the unfamiliar and unknown.

A life-changing experience could happen anytime. Going from constriction to freedom could happen anytime. Liberation from life's narrow places, or God's presence passing before us in such a way that we feel the presence of goodness, could happen right now. Our job is to be ready for the experience of being changed.

That kind of mindful living takes practice. College is busy. Life is busy. The life-changing experience of a moment may be a gift of grace, or a total accident. But good practice makes us accident-prone.

So here's a blessing for being prone to the best kind of accidents, the serendipity that can change a life in the blink of an eye, the two minutes that can last a lifetime, two minutes that can change a life.

This is the d'varling I offered tonight at the end of Kabbalat Shabbat services at the Williams College Jewish Association. (Cross-posted to Under the Kippah: Thoughts from the Jewish Chaplain.)

Image by Jack Baumgartner. [Source.]

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers