Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 89

April 11, 2017

Layers of Hallel, layers of time

On the first morning of Pesach I took my pocket siddur onto my mirpesset (balcony) and davened the psalms of Hallel. I sang them quietly enough not to disturb my neighbors, but loud enough to hear myself singing.

On the first morning of Pesach I took my pocket siddur onto my mirpesset (balcony) and davened the psalms of Hallel. I sang them quietly enough not to disturb my neighbors, but loud enough to hear myself singing.

I hadn't really spent time on the mirpesset since Sukkot ended. The weather got cold, I folded up the chairs and table, and I didn't go onto the balcony for months.

This was my first time back out there, and just like at Sukkot, I was singing Hallel. But unlike at Sukkot, this time I was sustained by memories of last time. When I sang these psalms at Sukkot I put down a first layer of spiritual experience in this place, and when I returned to them at Pesach, that first layer gleamed beneath the layer of the now and the new.

Sitting on my mirpesset now, I remember how it felt to have my little sukkah over me, spangled with autumn garlands. The location -- both physical (the mirpesset) and spiritual (the festival, the singing of Hallel) layers the now over the then, links what is and what was.

The festivals serve in this way regardless of physical location. Their melodic motifs in particular work this way for me, hyperlinking Pesach with Shavuot with Sukkot, one year with the last and with the next. But because my move last year was such a big deal for me (after seventeen years in that house, and eighteen years in that marriage), the shift from my old life to my new one was seismic in ways I'm only now beginning to recognize.

That, in turn, means there is extra comfort in beginning to put down roots here -- both in this physical place, and in this new chapter in which I am a single person rather than a partnered person, a divorcée rather than a wife. Singing hallel on my mirpesset from festival to festival helps to ground me in this new normal. And it's a piece of the life I had hoped to build for myself, and for that I am grateful.

מן המצר כראתי יה, ענני במרחב יה –– from the narrow place I called to You; You answered me with expansiveness.

Amen, amen, selah.

Deep Ecumenism and Being a Mixed Multitude

One of the things I love about the Passover story is that every year the story is the same, and every year I hear it anew. (This is true of the whole Torah, too, but I knew and loved the Pesach story before I knew and loved the whole Torah.) Every year we retell how we were slaves to a Pharaoh in Egypt and God brought us out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. And every year, something different about the story leaps out at me and says pay attention.

One of the things I love about the Passover story is that every year the story is the same, and every year I hear it anew. (This is true of the whole Torah, too, but I knew and loved the Pesach story before I knew and loved the whole Torah.) Every year we retell how we were slaves to a Pharaoh in Egypt and God brought us out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. And every year, something different about the story leaps out at me and says pay attention.

This year the thing that leaps out at me is the erev rav, the "mixed multitude" that went forth with us from Egypt. When we left Mitzrayim, tradition teaches, we did not leave alone. A mixed multitude came with us. One tradition holds that some Egyptians chose to leave with us, to strike out toward freedom and self-determination. Another tradition holds that even Pharaoh's daughter came with us, and in so doing acquired a new name: Batya, "Daughter of God."

I imagine us as a vast column of refugees walking together into the wilderness... and in that great crowd of people were people who were born into this community, as well as fellow-travelers who chose to accompany us on our journey toward freedom. Together they redefined identity, so everyone became an insider, not divided by label or practice. This is the story that constitutes us as a people, the story we retell every Pesach, the story we allude to in the kiddush every Friday night and in the Mi Chamocha prayer every single day -- and in this core story, we are a mixed multitude. From the moment of our formation as a community, we are diverse.

Immediately upon leaving Egypt, we came to an insurmountable obstacle: the Sea of Reeds. On Monday night, Ben Solis-Cohen gave a beautiful d'var about Nachshon ben Aminadav, the brave soul who took the first steps into the waters. Nachshon kept going until it seemed that he would drown, and then the waters parted. This is a story about trusting in something beyond ourselves and getting through adversity we didn't think we could get through. Because in and of ourselves, we couldn't. As a theist, I would say God accompanied us, and therefore we became more than we thought we could be. That language may or may not work for you, but what matters is this: when the journey ahead seemed impossible, we found the courage to keep going, and the impossible became possible.

This is the story that constitutes us as a people, and it's not entirely an easy story. After we came through the sea, the waters rushed back in and swept away the Egyptian armies that had pursued us. Midrash teaches that God rebuked the angels for rejoicing, saying, "My children are perishing, and you sing praises?" Both "we," and "they," are equally God's children. The story that constitutes us as a people demands that we ask what price is being paid for our liberation, and by whom. Whose bondage or suffering is the price of our freedom and comfort, and what right do we have to exact that price?

It's our job as Jews to rejoice in our freedom, and it's our job to look at this system, this community, this nation, this planet, and ask how and whether we're complicit in the suffering of others who are not yet free. What is the price of our spiritual freedom, and who is paying that price, and what can we do about that? And considering our complicity isn't enough. It's also our job as Jews to work toward liberation for everyone. Until everyone is free, our liberation is incomplete.

The mixed multitude who left Egypt included people who were not Jews... as our Shabbat dinners here include those who walk on other spiritual paths. On most Christian calendars today is Good Friday. In their tradition, today commemorates the death of Jesus on the cross. In their tradition, the price of spiritual freedom for humanity was the death of the rabbi they call Jesus who was both human and divine.

For our Christian friends, tonight is a dark night that will give way on Sunday to the brightest of new dawns. The emotional journey of going from Good Friday to Easter does for them what the emotional journey of Pesach can do for us. Remembering the tenth plague, the death of the Egyptian firstborns -- remembering the Egyptian army swept away in the Sea of Reeds -- impels us to recognize the preciousness of this life, and to cultivate openness to growth and change.

Following the teacher of my teachers, Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi z"l, I want to suggest that the best way we can relate to Good Friday is not by trying to be Christian, but by being all the more Jewish. This is what he called "deep ecumenism." From the authenticity of our spiritual practice, we can walk alongside others in theirs, partaking in a universal human journey that has multiple forms. And that journey would be darkened and diminished if even a single one of us didn't take part.

Every religion, Reb Zalman taught, is like an organ in the body of humanity. We need each one to be uniquely what it is, and we also need each one to be in communication with the others. If the heart tried to be the liver, we'd be in trouble, but if the heart stopped speaking to the liver, we'd be in even more trouble! Each community of faith -- including those who identify as atheist, agnostic, or secular -- needs to live up to its own best self, and each needs to be in dialogue with the others.

Humanity hasn't quite mastered this yet... but the rest of the world could learn a lot from Williams campus life. When the Chaplains' Office organizes a multifaith prayer experience after the desecration of Jewish cemeteries and Muslim mosques. When Williams Catholic, or Williams Secular, or the Feast, shows up to cook Shabbat dinner for WCJA. When Feminists of Faith gather on a Saturday afternoon, as we will do here on April 29. This is what it means to be a mixed multitude: not because we're stuck with each other, but because we embrace each other. Because our pluralism is part of who we are.

On Sunday night we'll enter into the seventh day of Pesach, which tradition says is the day when we actually crossed the sea. We'll remember how after crossing that sea, Miriam and the women danced with their timbrels, singing in gratitude to the One Who makes our transformation possible.

That's our job too: to sing out in praise. To cultivate gratitude and joy, without ignoring the things that are hard, either in our past or in our anticipated future. Miriam and the women are my role models in that. They'd experienced trauma and loss, they were on a journey with an unknown destination, they were carrying their whole lives on their backs -- and they danced anyway.

Miriam and the women teach me that no matter what I've been through and no matter what challenges lie ahead, there is always reason for hope and rejoicing. "Look around, look around: how lucky we are to be alive right now!"

This is the story that constitutes us as a people: a mixed multitude, welcoming and diverse -- growing and becoming, taking a leap of faith singly and together -- grappling with systems of oppression -- supporting each other on our various spiritual paths -- aware that transformation is always possible -- with hearts expansive enough to hold both life's adversity and life's joy.

We live into this story through every act of tikkun olam (healing the world) that we do singly and together: in our learning, in our fellowship, in our activism, in our prayer, in our community-building. Each of these is a step on the road to Sinai, a step en route to the land of promise awaiting us all.

This is the d'var Torah I offered tonight during dinner at the Williams College Jewish Association. (Cross-posted to Under the Kippah: Thoughts from the Jewish Chaplain.)

Image: "Multitude," by Sam Miller. (Source.)

April 10, 2017

Pesach is almost here!

Pesach is almost upon us!

Many of you may be scurrying around today making final preparations for seder -- but on the off-chance that you're looking for some thematic reading, here are some posts I've shared on Pesach themes over the years:

Passover, matzah, dialectics (2006)

On mindfulness and matzah (2007)

Birth (2008)

Exiting Mitzrayim (2009)

Matzah; open space; constriction (2012)

Leaving and Learning (2013)

Always more to learn [seder poem] (2014)

The seder as time machine (2015)

And the day came (2016)

Parsley dipped in tears and Cleaning the internal house (2017)

Also, if you’re still looking for a haggadah to use tonight, here is a link to mine, which is available as a free download: Velveteen Rabbi’s Haggadah for Pesach.

May your festival of Pesach be liberating and sweet!

April 8, 2017

Thanks, JWI!

Deep thanks to the folks at Jewish Women International for the lovely write-up on the Velveteen Rabbi's Haggadah for Pesach! Here's a taste:

Deep thanks to the folks at Jewish Women International for the lovely write-up on the Velveteen Rabbi's Haggadah for Pesach! Here's a taste:

“I know some people use my Haggadah whole cloth and some use excerpts with whatever Seder they are doing,” Barenblat told me when I spoke to her this week. “I am thrilled that it speaks to people. I hope it provides inspiration so people can relate to the story not as something that happened then, but as something happening now.”

“Anyone can be changed by the themes of the Seder,” Barenblat added. “It can resonate if you are ready.”

You can read their article here: A Powerfully Relevant Haggadah to Download.

Please know that I've asked them to make one correction to the article: the reading "Long ago at this season," which Sue Tomchin cites in the article, isn't mine. As the footnotes in my haggadah indicate, it's from Chaim Stern's Gates of Freedom.

If you're interested, please download the haggadah from the haggadah page on my website, here: Velveteen Rabbi's Haggadah for Pesach.

(The page on my website also has the cover file available for download, which is not available on the JWI page; and if and when I revise the haggadah, the most up-to-date version will always be available on my website, whereas the link on the JWI page may not always be the most-current version.)

Wishing everyone a meaningful Pesach!

April 7, 2017

Cleaning (the internal) house before Pesach

It's Shabbat HaGadol, "The Great Shabbat" -- the Shabbat that comes right before Pesach. Traditionally, this is the day when rabbis are supposed to give lengthy sermons on the importance of properly cleaning one's house for Pesach and getting rid of every crumb of leavenable grain.

It's Shabbat HaGadol, "The Great Shabbat" -- the Shabbat that comes right before Pesach. Traditionally, this is the day when rabbis are supposed to give lengthy sermons on the importance of properly cleaning one's house for Pesach and getting rid of every crumb of leavenable grain.

So that's what I'm going to do, except that mine will be very short, and mine isn't actually about housecleaning.

I mean, it's great if you want to remove the chametz from your dorm room, and by all means show up on Sunday to help us turn over the kitchen for Pesach here at the JRC! But tonight I'm less interested in the details of how to kasher a kitchen, and more interested in what this practice can teach us spiritually.

The word chametz (חמץ) comes from l'chimutz, to sour or ferment. In the world of tangible practicality, chametz means leavened bread, or things made from the five officially (according to Talmud) leavenable grains. But in the realms of emotion and thought and spirit, chametz can mean the old stuff in our hearts. Old patterns, old baggage, old hurts that we hold on to. The puffery of ego and pride. The sourness of old angers and insults. That thing somebody said, or did -- or that thing that we ourselves said or did -- of which we've never been able to let go.

Monday night we'll enter into the Festival of Freedom. Tradition teaches that we thank God on Pesach for what God has done for us in bringing us out of Mitzrayim -- not some mythic "them" back "then," but us, in our own lives, right now. The name Mitzrayim, usually translated as "Egypt," comes from the root צר (tzr), which means narrowness or suffering. We all experience suffering and inhabit narrow places. Pesach comes to remind us that we can leave emotional and spiritual constriction behind.

And when it's time to embrace change and new beginnings, we have to leap at that chance -- even if we don't feel fully ready, even if our bread dough hasn't had the time to rise. That's why our mythic ancestors baked unleavened bread for their journey. Walking in their footsteps, we too are called to leave behind our chametz, our old habits and patterns, the wounds we've been unwilling to forget, the disappointments that color our relationships with others and with ourselves.

Traditionally we search for chametz on the night before the holiday by the light of a candle. This practice comes to remind us that we find our chametz, the old and maybe painful stuff we need to relinquish, in darkness -- in the dark night of the soul, the tough times in our lives when light and hope seem distant and hard to find.

Clearing out internal chametz isn't easy. Often we feel resistance: we don't want to let go of an old story, or to forgive someone who's hurt us, or to believe that we ourselves can be forgiven for our missed marks. It requires some scrubbing, metaphysically speaking. Our work is discerning which of our old stories still serve us, and which have become chametz that we need to shed in order to move toward liberation.

There's a Zen parable about two monks whose vows instructed them not to touch women. They came to a flooded river and found a woman in need of transport across. One of them picked her up and carried her. After they reached the other side, the other monk fumed for about an hour, and finally burst out with "Why did you do that? We made a vow not to touch women!" The first monk looked at his friend and said, "I put her down an hour ago. Why are you still carrying her?"

What's the chametz you're carrying that you need to release in order to approach Pesach with unburdened shoulders? What's the old stuff in you that you need to clear away so that you can enter Pesach with a heart that is open and whole?

This is the d'varling I offered tonight at the end of Kabbalat Shabbat services at the Williams College Jewish Association. (Cross-posted to Under the Kippah: Thoughts from the Jewish Chaplain.)

There's a practice of ritually hiding, and then discovering and disposing of, some leaven on the night before Pesach. Here's a one-page handout containing the ritual, the blessing, and a poem: Bedikat Chametz [pdf]

April 3, 2017

Parsley dipped in tears

A few weeks ago, on a Friday morning, I walked with a dear friend in the Atlanta Botanical Garden.

A few weeks ago, on a Friday morning, I walked with a dear friend in the Atlanta Botanical Garden.

Where we live the world was covered with a winter coat of snow, but in Georgia the first stirrings of spring were underway. There were daffodils blooming, and leaves preparing to pop free.

But the thing that most drew my attention was one of the beds in the herb garden, filled with different varieties of parsley. The moment I saw the parsley plants growing, I tasted Passover.

The third step of the seder journey is karpas. We bless and eat something green, dipped in salt water. The green represents the new life of springtime, while the salt water represents the bitter tears of slavery.

There's a deep truth hidden in that bite of green. New beginnings may not come easy. Often they require hard work, and willingness to name and to take responsibility for what's been bitter.

We've all had moments when we feel as though whatever constraints we habitually inhabit are permanent. Maybe we've had moments of losing hope that whatever narrow place we're in -- depression, or tough life circumstances, or grief -- will ever be different.

But spring does come, even when winter feels most entrenched and unmovable. And Jewish tradition teaches that when we cry out from the depths of our lives' narrow places, there is One Who hears us and helps us to break free. And every year we retell the story: not as something that happened to them back then, but as something that is happening to us right now.

It's okay if the green of new life is bathed in salt tears, if our new growth is tender, if change sometimes hurts. That's exactly the flavor of the parsley dipped in salt water. Sharp, and intense, and a little bit salty: sadness for what was, mingled with hope for what's coming. Remembrance of the old, and embrace of the new.

March 31, 2017

Glimpses of a week in Alabama

There are so many things about my week in Alabama that I wish I could share with y'all.

There are so many things about my week in Alabama that I wish I could share with y'all.

The preaching at 16th Street Church in Birmingham last Sunday. I had thought I would miss the service, but the Jewish student and I who flew in that morning both arrived just in time, and holy wow, I have never actually seen preaching like that before.

The rosemary in the rose garden in front of the Presbyterian church where we stayed in Tuscaloosa, which I touched every time I went by, like a mezuzah. It scented my fingers, an olfactory hyperlink to many places and moments I have loved.

Building a "safe room" on our first day, in hard hats, on a bare slab on Juanita Drive, right in the heart of where the tornado devastated the city in 2011. Nailing two-by-fours together, framing walls, adding steel brackets, adding steel cladding -- to keep the inhabitants of that Habitat home safe if a tornado should come through town again.

Building a "safe room" on our first day, in hard hats, on a bare slab on Juanita Drive, right in the heart of where the tornado devastated the city in 2011. Nailing two-by-fours together, framing walls, adding steel brackets, adding steel cladding -- to keep the inhabitants of that Habitat home safe if a tornado should come through town again.

Leading our first evening discussion on brokenness and mending through the lens of Rabbi Isaac Luria's teaching about the breaking of the vessels and our obligation to lift up sparks. Connecting that with Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel's teaching about how when he marched in Selma, his feet were praying.

The quality and caliber of our conversations all week long. Each of my colleagues taught one night, and each offered beautiful teachings drawn from their own tradition. (You can see the four of us in one of the photos illustrating this post -- taken outside of Habitat for Humanity's office in town. They'll print the photo and tack it up on a wall there as part of their illustrated address book of people who've come through town to serve in this way.)

Crouching in a patch of clay outside one of our rehab homes with a Muslim student, showing each other how to write and pronounce the root of the verb "to write" in our respective holy languages. (In Hebrew it is spelled כתב - k/t/v. In Arabic it is k/t/b. We both beamed.)

Working on rehabilitating a home for someone in need. I was based primarily in her kitchen, putting doors and veneer on cabinets, tiling and grouting the backsplash, fitting baseboards and nailing down thresholds. I take comfort from knowing that when we leave, her home will be safer and more beautiful and more functional than when we arrived.

Working on rehabilitating a home for someone in need. I was based primarily in her kitchen, putting doors and veneer on cabinets, tiling and grouting the backsplash, fitting baseboards and nailing down thresholds. I take comfort from knowing that when we leave, her home will be safer and more beautiful and more functional than when we arrived.

Taking on a long list of carpentry and construction tasks that I had never done before. I'm comfortable now with a circular saw, a table saw, a mitre saw, two different kinds of tile saw, not to mention nail guns powered by compressed air. (Comfortable enough to maintain a healthy respect for them! But no longer afraid of them.)

Today (Friday) is our last day on our various job sites. We'll knock off slightly earlier than usual so we can return to First Presbyterian Church, clean ourselves and the church, and make our way to Birmingham. The coming Shabbat will feature Friday dinner and activities at the Islamic Society of Birmingham, Shabbat morning services and lunch at Temple Emanu-El, and afternoon mass at St. Francis Xavier before our closing reflections and havdalah.

As the week draws toward its close, my body is tired but my spirit is soaring. I'm endlessly grateful to my chaplaincy colleagues at Williams for the opportunity to take part in this extraordinary week, to our hosts at First Presbyterian Tuscaloosa and St. Francis Xavier Birmingham for putting us up, and to the kind and patient teachers at Habitat for Humanity Tuscaloosa who so graciously and warmly helped us believe in ourselves as we learned new ways to serve.

March 27, 2017

What silence conceals and reveals - at My Jewish Learning

...It’s easy to shy away from Leviticus. The middle book of the Torah, Leviticus is rife with the details of a sacrificial system we haven’t practiced in the better part of 2,000 years. (And most contemporary Jews have no interest in returning to pre-rabbinic Judaism, which makes Leviticus even more alien and alienating). The first portion in the book of Vayikra (Leviticus) is also called Vayikra. The word means “And God Called.”

The first word of this biblical book is characterized by a textual oddity. In Torah scrolls, which are still handwritten with quill and ink on parchment, the final letter of that first word is always written extra-small. (It looks like this.) The silent aleph (א) at the end of the word is written in miniscule.

Without that aleph, the word would mean “and God happened upon.” With the aleph, it means “And God called.” Midrash teaches that Moses wanted to write “vayikar,” without the final aleph — as though God had merely happened upon him. But God insisted otherwise God didn’t just “happen upon” Moses, but called out to Moses on purpose! In the end, they compromised: The letter is there, but it’s tiny.

Set aside for the moment whether or not you believe that Torah was given to Moses in full on Mount Sinai, and whether or not you believe that the details of scribal practice are divinely foreordained. What interests me about this story — this push-and-pull between Moses’ humility and God’s insistence that Moses has a role — is that it’s in our canon in the first place...

That's an excerpt from a longer piece I wrote for My Jewish Learning for the Torah portion Vayikra. Read it here: What silence conceals and reveals.

March 24, 2017

An interfaith service trip to Alabama (after Shabbat)

At the blessed crack of well-before-dawn on Sunday I'm heading south for what promises to be a truly extraordinary week.

At the blessed crack of well-before-dawn on Sunday I'm heading south for what promises to be a truly extraordinary week.

Each year, the chaplains at Williams College partner with the Center for Learning in Action on an interfaith service trip to Tuscaloosa, Alabama. (See Alabama Calling, Williams Alumni Review, July 2012.) This year I am profoundly blessed to be one of the chaplains serving my alma mater, which means I get to take part!

The four chaplains (Jewish, Christian, Roman Catholic, and Muslim) will travel to Alabama with a group of a dozen students from a variety of faith backgrounds. This year's group includes students who self-identify as Jewish, Christian, Roman Catholic, Muslim, Buddhist, Deist, and atheist.

We'll begin the week by visiting the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute (and those who are there on that Sunday morning will attend services at the 16th Street Baptist Church; I'm sorry to miss that, though am grateful that those of us who are flying in on Sunday morning will get there in time for the Civil Rights Institute.)

Then we'll spend the week working on a Habitat for Humanity building project together, building a home for someone in need and continuing to help our host community there recover from tornadoes that devastated the area a few years ago. We'll camp out in a local church social hall, and cook vegetarian meals together each night. (I've packed my sleeping bag. The whole thing is giving me fond memories of touring with the Williams College Elizabethans during my own undergraduate days.)

Each night a different chaplain will offer teachings on the shared theme of brokenness and mending. Those evening sessions offer an opportunity to introduce students to our four different faith-traditions, and also to get them talking with each other and with us about how the conversations we're having in the evenings relate to the holy work we're doing during the day.

Over the course of the week, as we engage with the civil rights movement and how that historic and historical struggle for human rights dovetails with today's politics, I expect that (alone and together) we'll wrestle with our own relationships to race and privilege. For most of us, the American South will be unfamiliar territory, so there's learning to do there. And for most of us, the kind of conscious multi-faith community we're aspiring to co-create will be unfamiliar territory, too. I suspect that all of us will find ourselves pushing up against our usual boundaries from time to time.

We'll seal the week with what feels to me like a gloriously multi-modal celebration of Shabbat: first we'll attend Friday dinner and activities at the Islamic Society of Birmingham, then Saturday morning Shabbat services and lunch at Temple Emanu-El, and then Saturday afternoon mass (or as I've been thinking of it, Shabbat mincha in a different key) at St. Francis Xavier, with havdalah as part of our closing reflections and integration work on Saturday night.

(As a student of the students of Reb Zalman z"l -- he who famously called himself a "Spiritual Peeping Tom" and said he liked to see how other people "get it on with God" -- I think that Shabbat sounds like an actual foretaste of heaven!)

I know that this will be an exhausting and overwhelming week -- and I anticipate that it will be at least as wonderful as it is challenging. I don't know that I'll manage to blog much while I'm away, but I imagine that I will harvest spiritual riches from this trip for a long time to come.

March 23, 2017

Looking ahead to the Omer

I have loved Pesach since I was a kid. All my life it has been the brightest star in my firmament, the holiday I look forward to the most. And many of the things that I loved about it when I was a kid are still things that I love! But part of the joy of coming to a mature adult relationship with the holiday has been discovering new facets to savor. One of those facets is a little practice that begins at the second seder -- the counting of the Omer. "Omer" means "measures," and the counting of the Omer is the practice of counting the 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot, between liberation and revelation.

This was not a big part of my childhood Pesach observance... and I had no idea as a kid that Pesach was the first step on the journey toward Sinai. But the winding path connecting our festival of freedom with our festival of revelation is a rich opportunity for contemplation and inner work. As the spring unfolds, so too can our hearts and souls.

If you're looking for resources for the Counting of the Omer, here are a few that I recommend:

Rabbi Yael Levy’s Journey Through the Wilderness: A Mindfulness Approach to the Ancient Jewish Practice of Counting the Omer

Rabbi Min Kantrowitz’s Counting the Omer: A Kabbalistic Meditation Guide

Rabbi Jill Hammer's Omer Calendar of Biblical Women

Rabbi Simon Jacobson's Counting the Omer

Lea Gavrieli's Counting the Days: Growing Your Family's Spirit by Counting the Omer

And if visual art speaks to you more than does text, try D’vorah Horn’s Omer Series of paintings, available on beautiful printed cards for $36.

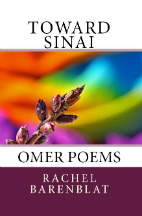

And, of course, there's my own Omer offering. Last year I released a collection of 49 Omer poems, one for each day of the count. It's called Toward Sinai, and it's available on Amazon for $12. Here's a description:

The Omer is the period of 49 days between Pesach (Passover) and Shavuot. Through counting the Omer, we link liberation with revelation. Once we counted the days between the Pesach barley offering and the Shavuot wheat offering at the Temple in Jerusalem. Now as we count the days we prepare an internal harvest of reflection, discernment, and readiness. Kabbalistic (mystical) and Mussar (personal refinement) traditions offer lenses through which we can examine ourselves as we prepare ourselves to receive Torah anew at Shavuot. Here are 49 poems, one for each day of the Omer, accompanied by helpful Omer-counting materials. Use these poems to deepen your own practice as we move together through this seven-week corridor of holy time.

The Omer is the period of 49 days between Pesach (Passover) and Shavuot. Through counting the Omer, we link liberation with revelation. Once we counted the days between the Pesach barley offering and the Shavuot wheat offering at the Temple in Jerusalem. Now as we count the days we prepare an internal harvest of reflection, discernment, and readiness. Kabbalistic (mystical) and Mussar (personal refinement) traditions offer lenses through which we can examine ourselves as we prepare ourselves to receive Torah anew at Shavuot. Here are 49 poems, one for each day of the Omer, accompanied by helpful Omer-counting materials. Use these poems to deepen your own practice as we move together through this seven-week corridor of holy time.

Praise for Toward Sinai: Omer Poems

Rachel Barenblat has gifted her readers with a set of insightful poems to accompany our journey through the wilderness during the Counting of the Omer. Deft of image and reference, engaging and provocative, meditative and surprising, this collection is like a small purse of jewels. Each sparkling gem can support and enlighten readers on their paths toward psycho-spiritual Truth.

— Rabbi Min Kantrowitz, author of Counting the Omer: A Kabbalistic Meditation Guide

Rachel Barenblat comes bearing a rich harvest. In Toward Sinai, her series of poems to be read daily during the counting of the Omer, a poem chronicles every step between Exodus and Sinai. The poems exist in the voices of the ancient Hebrews measuring grain each day between Passover and Shavuot, and also in a contemporary voice that explores the meaning of the Omer in our own day. Together, the poems constitute a layered journey that integrates mysticism, nature, and personal growth. As Barenblat writes: “Gratitude, quantified.”

— Rabbi Jill Hammer, author of The Omer Calendar of Biblical Women

Your Torah is transcendent and hits home every time.

— Rabbi Michael Bernstein, Rabbi Without Borders Fellow

Toward Sinai: Omer poems is available for $12 on Amazon. If you pick up a copy, I hope you'll let me know what you think and how and whether it shapes your Omer journey this year.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers