Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 91

March 1, 2017

Responding to fear with prayer and hope

In recent days, Jewish cemeteries have been vandalized and desecrated in St. Louis and in Philadelphia, and bomb threats at Jewish community centers and Jewish day schools are becoming commonplace. (There were 31 such threats on Monday; there have been more than 100 since the secular year began.)

My Facebook feed is filled with posts from friends whose children attend Jewish schools that got bomb threats this week, and friends who are grieving the desecration of the cemeteries where their loved ones are buried or the cemeteries where they provide pastoral care and preside over funerals.

Meanwhile, there was an arson attack on a mosque in Tampa, Florida -- the second such attack in Florida in six months. Four mosques have burned in the last seven weeks. Hate crimes against Muslims are at their highest since 2001. Hate crimes have risen massively, and the list continues growing.

My heart aches. I oscillate between grief and fury. I am not afraid -- I am fortunate enough to feel safe where I live and work and pray -- but I know that those who are more vulnerable than I, who occupy positions of less privilege by virtue of how they look or how they pray or where they live, are very afraid.

I can't do much to shift our national political climate. But I can take action in my own community to stand against hatred, anti-Semitism, and Islamophobia, and to stand with friends of many faiths in affirming that our differences are holy and that we stand in solidarity with each other in times of need.

The Chaplains' Office at Williams College is putting together an interfaith opportunity for prayer and togetherness for next week. We'll begin in the Muslim prayer space on campus, where the Jewish students and chaplain will offer a prayer for those impacted by Islamophobia and the fire at the mosque, and then in their sacred space we will say the prayers of our afternoon mincha service.

Then we'll walk together from there to the Jewish prayer space on campus, where Muslim students and chaplain will offer a prayer for those impacted by anti-Semitism and by the cemetery desecrations, and then in our sacred space they will say the prayers of their maghrib sunset worship.

There are a few things I love about this intention. One is that we will be consciously sharing our sacred spaces with each other, and saying our own late-afternoon prayers in each others' sacred spaces. (And for any participants who are neither Jewish nor Muslim, they'll have an opportunity to respectfully be present and bear witness during a few minutes of prayer in each of those traditions.)

I also love the fact that we'll be praying for each others' wellbeing. Jews will pray for the wellbeing of Muslim communities and sacred spaces (both local and global), and Muslims will pray for the wellbeing of Jewish communities and sacred spaces (both local and global). This shouldn't be a radical act, though today's political climate often mitigates against this kind of basic human connection of love and care.

And I love the fact that we're standing against terror and fear -- against arson and desecration -- against bigotry and hatred -- by coming together in companionship, prayer, and hope. I know that what we do on our small campus in our small town won't change national or global realities, but it might shift our own internal spiritual realities, and the prayerful connections it will strengthen will strengthen us.

Related news stories:

Jews supporting torched Tampa mosque $18 at a time (JTA)

Muslims give money to Jewish institutions that are attacked (New York Times)

Muslim students in Florida send flowers to Jewish organizations, synagogues (JTA)

Standing in Solidarity With Our Jewish Friends (Cordoba House)

Muslim Veterans Offer to Guard Jewish Spaces Across the US (JTA)

Jews Hand Muslims Synagogue Keys When Texas Mosque Burns (The Forward)

February 28, 2017

Gaze

I want to gaze at you

not through lowered lashes

protecting my tender places, but

heart splayed wide

to everything I learn

when I let myself be seen.

I want to gaze at you

without flinching, knowing

what you'll find in my eyes:

my aches and imperfections,

the cracks in my clay heart,

the tarnish clouding my silver.

I want to see all of you

even if your pure light

would burn out my circuits,

even if all I can glimpse

is your shadowed silhouette

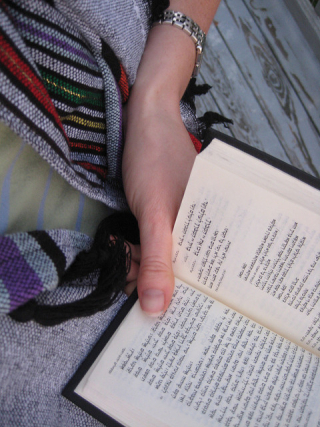

through my sheerest tallit.

If I bring my whole self

to yearning for you, if I seek

to see and to be seen wholly

can I call forth

the you who would be

in relationship with me?

[C]racks in my clay heart. Jewish tradition describes the broken-open heart as a clay vessel; see Vessel (2008) and A crack in everything (2016).

[E]verything I learn / when I let myself be seen. Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, the rabbi of the Warsaw Ghetto, teaches that when we relate to God as a "you," with willingness to bring our full selves to the experience, we receive revelation -- though it's not entirely clear whether it's revelation of God's self, or revelation of our own deepest self.

[E]ven if your pure light / would burn out my circuits. See parashat Ki Tisa. No one can look upon God and live; even Moshe only gets to see God's afterimage.

[T]he you who would be/ in relationship with me[.] This draws on another teaching from Kalonymus Kalman Shapira: when we stand in real relationship to God in prayer, we call forth the "Thou" with Whom we yearn to be in relationship.

This is another poem in my ongoing Texts to the Holy series, a collection of love poems to the Beloved / beloved (capital-B or lowercase-b, whatever resonates most for you.)

Offered with thanks to Rabbi Brent Chaim Spodek of Beacon Hebrew Alliance for introducing me to this text from Aish Kodesh by Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, also known as the Piaseczyner Rebbe, this past Shabbat afternoon.

February 27, 2017

Coming soon to Temple Sinai

This coming Sunday I'll be the featured poet at the eighth annual Jewish Poetry Festival at Temple Sinai. Temple Sinai is at 50 Sewall Avenue in Brookline, MA.

I'll be sharing poems at 2pm, followed by Q-and-A. I'm planning to share some poems from Open My Lips (Ben Yehuda, 2016) and from 70 faces: Torah poems (Phoenicia Publishing, 2011), as well as a few poems from my as-yet-unpublished next collection Texts to the Holy.

My reading will be followed by an open mike (sign up at the door to share your own poem on themes of family, community, and/or Jewish life) and snacks.

After the reading I'll have books for sale, and am happy to inscribe them for you. I hope to see some of you there!

For more information: 8th Annual Jewish Poetry Festival at Temple Sinai.

February 22, 2017

Intensive care

A few weeks ago I received a couple of photo albums in the mail from my parents. One of them contained photographs from the first months of my life, beginning with the weeks I spent at what they then called "the neonatal unit." (Today the standard name for such a ward is NICU, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. When I was born, the hospital at which I was born didn't have a NICU, so they rushed me to Santa Rosa. Today most hospitals have at least some capacity for neonatal care.)

That's me, about a month old, in an incubator at the neonatal unit at what was then known as Santa Rosa Children's Hospital -- now called The Children's Hospital of San Antonio. I spent forty days and forty nights there before I was well enough to go home. The number feels symbolic to me, since in the rabbinic understanding, that's a period of time that represents maturation, fruition, and change.

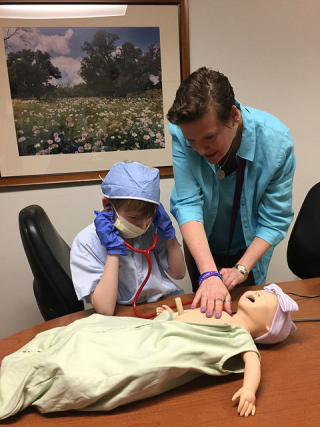

While visiting Texas with my son, I had the opportunity to visit Santa Rosa again with my parents and my son: not only to see the current neonatal unit (which I had seen once before), but also to visit the even newer NICU that they're building now.

Because of hospital regulations, my son couldn't go into the NICU, but he had the opportunity to use a stethoscope to listen to the heart of the baby mannequin they use in training, and to learn a little bit about the kind of care they provide to babies who are born too soon.

The whole visit was extraordinary, though there were two parts that were especially special for me. One was having the opportunity to walk through the NICU and say silent prayers for the babies who are being cared-for there. Sister Michele O'Brien told me that they are able now to operate on babies whose hearts are the size of a quarter. Dr. George Powers, who led us on our tour, showed us the equipment they use now and explained how it differs from what they had at their disposal when I came into the world.

The other thing that was special for me was visiting the hospital chapel with my son. When one first walks into the Children's Hospital, the chapel is the first thing one sees, which is intentional: a reminder that spiritual life and care are at the heart of what they do. It's a beautiful chapel, unsurprisingly, and we spent a few moments sitting there in contemplation.

There's a little metal "tree" in the back of the chapel. People are invited to write prayers on colored paper hearts and to hang them on the tree, and when the tree fills up, the hearts are taken out into the surrounding grounds and buried there, because -- in Sister Michele's words -- the place where the hospital stands is holy ground.

My son took a heart and carefully wrote "Thank You God for this," and then he paused. "Mom, can you write 'hospital'?"

I wrote "hospital," and he hung the heart on the tree.

Thank You God for this hospital indeed.

With gratitude for everyone at the Children's Hospital of San Antonio and the extraordinary work they do to provide care for families in need.

February 17, 2017

Yes we said yes we will yes

In this week's Torah portion, the children of Israel tell Moses, כל אשר דבר ה׳ נעשה / "All that God has spoken, we will do." After that, they receive the Ten Commandments.

In this week's Torah portion, the children of Israel tell Moses, כל אשר דבר ה׳ נעשה / "All that God has spoken, we will do." After that, they receive the Ten Commandments.

Wait. Doesn't that seem backwards? How could we accept the mitzvot, and only then learn what they are? How does it make sense to to agree to do, before we've heard what it is God is calling us to do? Almost every Torah commentator under the sun tackles this question, because it's a big one.

Lately I'm spending quality time with Menchem Nachum of Chernobyl, the Hasidic master also known as the Me'or Eynayim. And he says this is a teaching about how spiritually, no one ever stands still.

We're always rising and falling. Life-force ebbs and flows. Our connection with God ebbs and flows. Sometimes we feel connected with something beyond ourselves, and enlivened by that connection. Sometimes we feel we've fallen away and meaning is nowhere to be found.

Our task -- he says -- is to remember that all of creation is filled with divinity, that (in the words of the Zohar) לית אתר פנוי מיניה / there is no place devoid of the Presence. It's easy to feel that at spiritual high moments when we're feeling connected and full of love. It's harder to feel that when life is difficult and God seems distant.

When we feel that we've fallen far from God, when we feel conscious of our shortcomings that keep us feeling disconnected, when we're feeling existentially lonely, that's when we need to remember that there's no such thing as "far from God." God, he teaches, is never absent or far away -- only sometimes very hidden. God withdraws in order to make space for us, or perhaps to encourage us to seek.

When we feel that we're far away from God or from goodness, God is actually right there with us in our feelings of exile, our feelings of loneliness, our feelings of despair. Sometimes everything seems clear and we can feel God's presence with us. Sometimes the clarity departs and God feels far away. But the distinction is one of epistemology, not ontology.

And the answer to feeling existentially far-from-God is to say yes -- even when we can't feel the presence of the thing we're saying yes to. Say yes to life, even if you don't know where life will take you. Say yes to spiritual practice, even if you don't know how spiritual practice will change you. Say yes to the mitzvot, even when you don't wholly know what they are. Say yes to God, even if you aren't sure God exists, or is listening.

Agreeing to do before we've heard what it is we're supposed to do is an inversion. It's rising before falling. But the thing about falling is, it just spurs us to want to rise higher. One step back, two steps forward. At least, that's the Me'or Eynayim's take on it. Because spiritual life never stands still.

Standing still is stasis, and stasis is death. As long as we're living, we're growing and changing. My seven-year-old likes to say there's no such thing as doing "nothing" -- even if we're holding perfectly still, we're breathing, we're existing, blood is pumping through our veins. If we're alive, we're changing. In the Me'or Eynayim's terms, if we're alive, we're rising and falling.

We agree to do the mitzvot -- that's a moment of rising. Then we fall, because that's how life works. We touch elevated consciousness for long enough to give God an existential "yes we said yes we will yes," and then we fall away. But in our falling, we listen for God's presence in the world, and that's when we hear the Voice issuing forth from Sinai. שמע: we listen, and achieve a glimmer of understanding, and rise up again.

The first step is a leap of faith: כל אשר דבר ה׳ נעשה / "all that God has spoken, we will do." We leap even though we don't know what we're leaping to. We leap, saying "sure, we'll spend our lives with You" before we really know Who God is or where God might take us. We leap knowing that we will fall... and that from our place of having-fallen, we can rise to greater heights.

This is the d'varling I offered at WCJA at Kabbalat Shabbat this week. The teaching from the Me'or Eynayim that I cite here can be found in Hebrew in the app ובלכתך בדרך; if you'd like to read it in English, there's a translation at sefaria.

February 16, 2017

Davening: together, even when we're apart

Many years ago when I was in rabbinic school I used to daven one morning a week with a telephone minyan of rabbinic school friends. We were all in the eastern time zone, in states scattered across the country. We used a conference call phone line. We took turns leading davenen. It was a gift to me to hear the voices of beloved hevre, not to feel alone in my spiritual practice. Of course, the technology posed some challenges. If we wanted to sing along, we had to mute our own phones, otherwise our voices would cancel each other out. And eventually that telephone minyan came apart at the seams. Still, it was sweet, for a time.

Many years ago when I was in rabbinic school I used to daven one morning a week with a telephone minyan of rabbinic school friends. We were all in the eastern time zone, in states scattered across the country. We used a conference call phone line. We took turns leading davenen. It was a gift to me to hear the voices of beloved hevre, not to feel alone in my spiritual practice. Of course, the technology posed some challenges. If we wanted to sing along, we had to mute our own phones, otherwise our voices would cancel each other out. And eventually that telephone minyan came apart at the seams. Still, it was sweet, for a time.

In more recent years I've participated a few times in davenen via zoom, the videoconferencing app we use in ALEPH for Board meetings and other conversations. I have powerful memories of the Monday morning after Reb Zalman died, when the rest of the ALEPH Board was together in Oregon and I was far away in Massachusetts. I joined them via zoom that morning, and davened and sang and wept with them. I remember feeling like we were truly together. Of course, it helped that I knew everyone in the room; we were already a community. I remember being grateful that there was a way for me to be with them from afar.

The technological tools available to us for this kind of virtual community keep evolving. One recent morning shortly after I arrived at work at the synagogue I opened up Facebook to share a piece of synagogue news on my shul's Facebook page, and saw that Shir Yaakov was davening the morning service on Facebook Live. As is usual for me these days, my early morning had not offered me time for davenen. Early mornings in my house, these days, are all about getting myself and my kid fed and dressed, packing our lunches, making sure we both have what we need for the day ahead, and getting him on the schoolbus on time.

But here was one of my hevre davening in a way that I could join. It felt like a reminder from the universe of how I really ought to begin my work day! So I put on tallit and tefillin and sang with Shir. In the chat window alongside the video there was a steady stream of comments from others who were davening too. He asked us to name the places we were in, and the places for which we were praying. I saw the names of friends across the continent, and the names of people I don't know. From time to time a wave of little hearts would flow across the screen as people clicked on Facebook's "heart" button to share their love.

After the minyan ended I found myself thinking about how davenen connects us across places and times. Part of what's meaningful for me in davenen is knowing that others are singing these words too -- or perhaps other words that evoke these same themes -- around the world. As the hour for morning prayer moves across the globe, daveners enter in to morning prayer, together and alone. And there's also a way in which davenen connects us not only across time zones but across time -- some of these words have been recited in prayer for centuries, and will be recited for centuries to come.

In in the world of assiyah (geographically), those of us who joined this Facebook Live minyan were all over the place. But -- at least for a while -- in the worlds of yetzirah (emotion), briyah (thought), and atzilut (spirit), we were all together. Sometimes when I gather with community in person, we're in the same place physically but our hearts and spirits aren't necessarily aligned. Someone's distracted, someone's focusing on this morning's news, someone's grieving, someone's angry with someone else in the room -- there are all kinds of reasons why we can be disconnected. But at its best, prayer connects us both in and out -- with ourselves and with each other -- and also up.

("Up" is a metaphor, of course. As I taught my students last night in our intro Judaism class, Judaism's God-concepts include both transcendence and immanence, the Infinite and the relatable. God is in the vastness of spacetime, and as intimate to us as the beating of our own hearts. My favorite metaphor for God these days is Beloved. The God to Whom I need to relate right now is the One Who sees me and loves me in all that I am. Prayer doesn't always connect me with that One... but as with any other practice, the only way to reach the times when it "works" is to keep doing it even at the times when I feel like it "doesn't work.")

At its best, prayer connects us with our deepest selves, and with our Source, and with each other. No matter where in the world we are. Even when we feel most alone, when we "log in" to the cosmic mainframe (that's language Reb Zalman z"l used to use), we're connecting with the Network that links us all. Prayer can remind us to open our hearts. It can attune us to the subtle movements of soul. And though sometimes when I pray with others I feel that I am still alone, sometimes when I am praying alone I can remember that what appears to divide us is illusory, and what connects us -- always -- is infinite and deep.

Related:

Visitation, a tele-davenen poem, 2008

February 11, 2017

Haggadah for Tu BiShvat (5777)

It's Tu BiShvat, the New Year of the Trees!

A few people have asked for copies of the digital haggadah we used at our Tu BiShvat lunch seder. Here it is:

Tu BiShvat Haggadah 5777 / 2017 from Rachel Barenblat

Enjoy!

My strength balanced with God's song: a d'varling for parashat Beshalach

This morning we sang excerpts from the Song at the Sea. We sang my favorite line from that song: עָזִי וְזִמרָת יָה וַיְהִי–לִי לִישֻעָה.

This morning we sang excerpts from the Song at the Sea. We sang my favorite line from that song: עָזִי וְזִמרָת יָה וַיְהִי–לִי לִישֻעָה.

That line is often translated as "God is my strength and my might, and will be my deliverance." But zimra doesn't mean "might," it means "song" -- as in psukei d'zimra, our poems and songs of praise. Sometimes I translate this line as "God is my strength and my song, and will be my salvation." I like the idea that both my strength, and my song, are ways of finding God. But the best translation I know is Rabbi Shefa Gold's translation (and by the way, she also wrote the melody for this verse that we're singing this morning): "My strength (balanced with) God's song will be my salvation."

My strength, balanced with God's song, will be my salvation.

Some of us may be allergic to the word "salvation," which feels kind of... Christian, somehow. Though of course the notion of a God Who saves us was a Jewish idea long before the birth of Rabbi Jesus. One paradigmatic example of God's salvation is the crossing of the Sea of Reeds -- which is in today's Torah portion. God parted the waters and we came through. We sing about it every week when we sing Mi Chamocha -- "the water is wide..."

Y'all probably know by now that I don't understand this as a historical story. This is a true story in the way that great literature is true. This is a true story because it speaks to one of our deepest human hopes: that when we are in tight places, we will find a way out. That when we are trapped between an advancing army and the sea, we will find a way through. That if we step into the sea, if we cultivate faith in a better future, we can partner with something beyond ourselves to bring that better future into being.

We partner with something beyond ourselves. My strength, balanced with God's song.

We need our own strength in order to cross the sea, to face whatever difficulties arise in our lives -- and every life holds tsuris, "suffering," which comes from the same root as Mitzrayim, "the Narrow Place." Every life has times when we feel trapped in the narrowness of our own circumstance. Life's challenges call forth our strength. Our task is to feel our own strength flowing through us, and to know that we have the inner resources the moment demands.

And we need God's song in order to cross the sea. We need music that uplifts the heart. We need love to sing its melody in us. We need hope, and heart-opening, and joy. If we try to cross the sea without those things, we might manage to walk across the sand, but we'd be like the figures in the midrash who were so busy kvetching about the muddy sea floor that they forgot to notice the miracle all around them, and as a result, when they reached the other side they weren't really free.

My strength, balanced with God's song. That's what gets us across the sea. That's what gets us from the narrow place into expansiveness. That's what enables us to experience spiritual growth and transformation. Our own core strength, balanced with the ineffable: with song and joy, with meaning and love.

This is the d'varling I gave at my shul this morning (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

February 10, 2017

What's rising in you? - a d'varling before Tu BiShvat

Tonight is the full moon of the month of Shvat, which means that it's Tu BiShvat -- the new year of the trees. (I realize that here at WCJA you'll be celebrating Tu BiShvat next weekend. You get a week-long holiday! But tonight is the full moon -- on some secular calendars it's called the Full Snow Moon.)

Tonight is the full moon of the month of Shvat, which means that it's Tu BiShvat -- the new year of the trees. (I realize that here at WCJA you'll be celebrating Tu BiShvat next weekend. You get a week-long holiday! But tonight is the full moon -- on some secular calendars it's called the Full Snow Moon.)

Tu BiShvat is the first step toward springtime. I say that with awareness that the world around us does not look much like springtime right now. In Williamstown, mid-February means snow and ice, not soft spring breezes and almond blossoms. For me, that makes Tu BiShvat all the more meaningful, because Tu BiShvat becomes a holiday about hiddenness.

The Jewish mystics have a lot to say about what's hidden and what's revealed, נסתר and נגלה. The world we live in is a world of surfaces, and everything conceals deeper meaning and hidden sparks. On the surface, Tu BiShvat might seem to be about establishing an age for trees so that their fruits can be tithed. That's how the holiday originated, back in Talmudic times. But deep down -- say the mystics -- it's really about the spiritual sap of the universe beginning to rise for the spring to come.

It seems appropriate that this holiday remind us to pay attention to what's unseen. The outside world may be covered with snow, but deep down under the snow the roots of the trees are soaking up the water that will feed the sap that will support next summer's verdant greenery -- at least, that's what Jewish tradition teaches. Our work is to trust in the spring that we can't yet see.

Torah says that human beings are like trees of the field, and we too have hidden undercurrents that aren't always visible to the naked eye. As we move through this midwinter full moon, what is rising in you? What hopes are you nurturing, deep down in your most secret heart? What yearnings are enlivening you, even if you haven't spoken them aloud?

What gifts might you be able to bring to the world by the end of this semester? When the trees have leafed out, all chartreuse and fluttering in the spring breeze -- when the lilac bushes in front of the President's house bloom and scent the spring air -- what new ideas or artwork or music or activism or relationships might you bring into being?

That's what Tu BiShvat is about for me: the sap of our hopes, the sap of our dreams, the sap that will fuel our work in the world. Imagine your feet planted in the earth like roots. Reach deep down into the earth and draw up the sustenance you need. With every beat of your heart, you can draw up more hope, and more of the energy you'll need in order to create.

On the outside, the world looks like winter -- but in the heart of every tree, the first stirrings of spring are rising. This full-moon midwinter Shabbes, celebrate what's rising in you.

This is the d'varling -- the short-and-sweet teaching -- that I offered at the Williams College Jewish Association tonight at Kabbalat Shabbat services.

February 9, 2017

Winter prayer among the trees

"This is where I like to explore," my son tells me. To an adult eye, this is the smallish band of trees and underbrush between our condo development and the condo development down the road, but to him these are The Woods.

I remember exploring the woods across the street from my house with my friends who lived down the block, when I was a kid, and I am grateful that he has a place like this where his imagination can soar.

"Thank you for showing this to me," I reply, as I follow him.

"This is a place where we can talk to God," he offers.

"Thank You God for the beautiful snow," I say, feeling tickled that this is still something he and I can do. I know that someday he will outgrow the desire to let me overhear his conversations with God, but that hasn't happened yet.

"This is the special place where I feel God's spirit," he tells me. "When you cross through here, you put your hands like this." He brings his hands together in prayer. I'm not sure where he learned that posture, but I am not about to argue with him. Here in his special place, he is the guide and I am the student.

"Thank You God for the woods that you made and for the snow on the trees and for this place where we can talk to You," he says, and then emerges from the sacred grove. "You try," he tells me.

I cross into the place where he was standing and I emulate his posture. "Thank You God for this beautiful snow, and for the trees, and for my wise son who teaches me things every day. Amen."

He beams at me. "Thanks, Mom," he says. "Let's go explore some more."

So we do.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers