Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 92

February 6, 2017

Dave Bonta's Ice Mountain

I've been a fan of Dave Bonta's poetry for a long time. (I reviewed his chapbook Odes to Tools at the Best American Poetry blog some years ago.) So when I learned that his new collection was coming out from Phoenicia Publishing -- the same press that brought out his Odes to Tools (and, full disclosure, also the same press that published my first two books of poetry, 70 faces and Waiting to Unfold) -- I pre-ordered a copy instantly.

I've been a fan of Dave Bonta's poetry for a long time. (I reviewed his chapbook Odes to Tools at the Best American Poetry blog some years ago.) So when I learned that his new collection was coming out from Phoenicia Publishing -- the same press that brought out his Odes to Tools (and, full disclosure, also the same press that published my first two books of poetry, 70 faces and Waiting to Unfold) -- I pre-ordered a copy instantly.

Ice Mountain: an elegy is spare, elegant, and deeply moving. These are daily poems arising out of walks on Dave's home territory, a mountain which he describes in the foreword as "a high section of the Allegheny front across the valley to the northwest of our own mountain," in 2013 "desecrated by an industrial wind plant[.]"

In that introduction he writes eloquently about the price paid by wildlife for those wind turbines, and about the extent to which the Appalachians remain a "national sacrifice area" in our perennial quest for cheap energy.

The introduction offers a geopolitical framing. The poems simply offer windows into the landscape, interspersed with Beth Adams' linocut prints, as spare and elegant as the words themselves.

Some of them explore an interior landscape that hints at the outside world, like this one:

4 February

In a dream I run

through my half-remembered high school

still an outcast

I grew up with a woodstove

instead of a television

I know all the theme songs of oak

the crackle and bang

the hiss and whistle

and sudden sigh of collapse

I love "all the theme songs of oak," and how the phrase "sudden sigh of collapse" hints at (but does not directly reference) the ecosystem in distress.

Others are explicitly about the mountain and its power installation, and hint at an interior world, like this one:

4 March

Ice Mountain's propellors

spin at different speeds

face this way and that

you can't hear them from here

their low-frequency moans

like lost whales

what won't we sacrifice

to keep the weather just right

inside our homes

I love that he compares the propellors to whales -- lost indeed, so far from any ocean -- seeing even in their deadly monstrosity an analogy to something found in nature.

The natural world and the manmade world are always in uncomfortable proximity here, as in this poem:

15 March

the highway's tar has been bleached

by a winter's worth of salt

and in the mid-day sun

it almost shines

I squint at the shapes on the shoulder

as I pass

here some saltaholic's crumpled fur

there a fetal curl

of flayed tire

Dave resists easy binaries. There is a kind of beauty in the salt-bleached highway that "almost shines." But our human needs for progress come at the cost of animal lives, and this collection never lets us forget that.

Because it is deep midwinter in the hills where I live, I am most drawn to the February and March poems, the ones that unlock the austerity and beauty of winter landscape. The summer poems feel dreamlike to me now, both in their beauty and in their dark undertones. I'm looking forward to rereading this collection at different times of year and seeing what speaks most to me on future re-readings.

Ice Mountain: an elegy is available at Phoenicia Publishing.

February 5, 2017

Waking up, and waking again

One of the pieces of my work at Congregation Beth Israel for which I am most grateful is our Friday morning meditation minyan. We call it a "minyan" in recognition of the fact that the term can mean both the time of prayer ("I'm going to morning minyan") and the group that prays (a minyan is the quorum of ten adult Jews required by tradition for communal prayer that involves a call-and-response), but it's not a formalized group and there is no formalized prayer -- just sitting in meditation.

One of the pieces of my work at Congregation Beth Israel for which I am most grateful is our Friday morning meditation minyan. We call it a "minyan" in recognition of the fact that the term can mean both the time of prayer ("I'm going to morning minyan") and the group that prays (a minyan is the quorum of ten adult Jews required by tradition for communal prayer that involves a call-and-response), but it's not a formalized group and there is no formalized prayer -- just sitting in meditation.

The fact of this standing Friday morning meditation group is one of the things that drew me to CBI, back when my dear friend Reb Jeff was the rabbi and I was just beginning to contemplate whether I might be ready for rabbinical school. I figured, if this were a synagogue where people meditate and are interested in Jewish contemplative practice, it might be a good home for me. (Turns out I was right about that!) I've kept the minyan going since I began to serve the community as its rabbi in 2011.

Our practice is simple. We begin in silence. After about fifteen minutes I offer a very short teaching, or guided meditation, or practice. (Most recently our practice had to do with cultivating compassion for ourselves and others. Often I offer a meditation designed to help us release the week in preparation for Shabbat.) After another fifteen minutes, we close with a three-breath practice from Thich Nhat Hanh that I learned from my friend and colleague Rabbi Chava Bahle, and with a niggun.

I love sitting in companionable silence in our beautiful sanctuary. Sometimes sunlight streams in through the big windows; sometimes snow falls outside. Sometimes we hear the rooster crow next door. And at the end of our practice time, I love opening my eyes and seeing the dear souls who have joined in over the course of the morning. Emerging from contemplative practice can feel like opening my eyes in the morning -- leaving what is almost a dream-state, waking up to a new reality.

And immersing myself in prayer or contemplative practice can feel like a repeated opportunity to wake up. In my experience, spiritual life is characterized by a kind of ebb and flow between wakefulness and sleep. I wake up (to the realities of the world around me, or to my own inner life, or both) and then I fall asleep again, and then I notice that I'm asleep and wake up. Rinse, lather, repeat. Spiritual life is a perennial process of noticing where I have been asleep, and waking up again. And again.

There's a story about the teacher of my teachers, Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi z"l (of blessed memory) -- actually, it's about one of his children. His daughter asked him, "Abba [Father], when we're asleep we can wake up. When we're awake, can we wake up even more?" (His answer, of course, was yes -- as is mine. We can always wake up even more. Our daily liturgy blesses God Who wipes the sleep from our eyes, and I understand that as a truth both in the physical realm and the spiritual realm.)

Waking up even from our ostensible wakefulness is part of what spiritual practice is for. Prayer and meditation can help to wake us up -- even if we think we're already awake, we can always wake to deeper truths, to higher levels of reality, to the work we are here to do in the world. (Spiritual direction can also be a tool that helps us wake up to who we are called to be.) I'm grateful to my Friday morning meditation group for their willingness to return and return again to the work of waking up together.

Related:

A Short History of Jewish Meditation, 2014

and the posts in the "contemplative practice" tag here, from various years

February 4, 2017

Exile and expansiveness - a d'varling for parashat Bo

Right now in our cycle of Torah readings (parashat Bo) we're reading about the plagues and the start of the Exodus. Looking for inspiration on this week's parsha, I turned to the Hasidic master known as the Me'or Eynayim, "The Light of the Eyes." (His given name was Menachem Nachum of Chernobyl.) He writes about Egypt as a place of existential exile, and about what happens to us spiritually when we are brought forth from there.

Right now in our cycle of Torah readings (parashat Bo) we're reading about the plagues and the start of the Exodus. Looking for inspiration on this week's parsha, I turned to the Hasidic master known as the Me'or Eynayim, "The Light of the Eyes." (His given name was Menachem Nachum of Chernobyl.) He writes about Egypt as a place of existential exile, and about what happens to us spiritually when we are brought forth from there.

Slavery in Egypt is our tradition's ultimate example of גלות / galut, existential alienation from God. It's the paradigmatic example of constriction. When we talk about being slaves to a Pharaoh in Egypt, we're also always talking about experiences of constriction in the narrow places of our lives now.

For the Me'or Eynayim, galut is a state of not-knowing God. It's a state of having fallen so far from unity that we don't even realize we've fallen. This, he says, is what we experienced in the Narrow Place. And Pharaoh is the exemplar of exile. He saw himself as a god, and had no awareness of a Source greater than himself.

When one is in this kind of galut, it's hard to know the difference between what will give life and what will deaden us. Torah instructs us to "choose life," but it's hard to know what will enliven us when we're in a place of alienation from our Source. What the Exodus offers us is the opportunity to leave existential exile, and in that leaving, to regain the capacity for moral choice.

In the state of galut that we experience when we're in life's Narrow Places, there's only katnut-consciousness, small mind. It's a vicious cycle, because exile creates small mind, and small mind makes it hard to imagine breaking free from exile.

Emerging from the Narrow Place means being reborn from katnut into gadlut, from small mind into expansive consciousness. The words גלות / galut and גדלות / gadlut are similar, but there's one letter of difference between them: the letter ד / daled, which -- as I was powerfully reminded by Rabbi David Ingber in his extraordinary sermon on doorways and welcoming the stranger last night -- is a delet, a door. Galut is exile; gadlut is greatness, or expanded-mind. We begin in exile. We go through a door, a transformation, a state-change. And then we reach gadlut, "big mind." And once we've reached expansive consciousness, we can seek to know God wholly. That's why we were brought forth from Egypt, says the Me'or Eynayim: in order to know God wholly.

We were brought forth from Egypt in order to see beyond the binaries of our own constriction. Once we begin to glimpse gadlut, the constrictions of exile fall away.

Exile can be self-perpetuating, because when we're in it, it's hard to see a way out. Depression is like that. Despair is like that. Overwhelm is like that. Sometimes if I look at everything that's wrong with the world, exile rushes in and washes me away. But if we can open our minds even for an instant to glimpse the prospect of a better life, the fact of glimpsing a redemptive possibility makes that redemption possible.

Shabbat is our chance to glimpse the world redeemed -- to live for one day a week not in grief at the world as it is, but in celebration of the world as it should be. May we emerge from Shabbat ready to roll up our sleeves, to combat small-mindedness wherever we find it, and to choose to bring more life everywhere we go.

This is the d'varling (brief d'var Torah) I offered at shul this morning. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

Worth watching: an incredible sermon on doorways

Rabbi David Ingber's Friday night sermon from Romemu last night is some of the most powerful preaching I've ever seen. It's about doorways. I don't want to say any more, because I don't want to spoil it for you. Take 20 minutes and watch or listen to it -- it is extraordinary.

(If you can't see the embedded video, here's a link at youtube.)

February 3, 2017

With what we are to serve - a dvar Torah for WCJA

In this week's Torah portion, Moses argues with Pharaoh about letting the people go.

In this week's Torah portion, Moses argues with Pharaoh about letting the people go.

It's framed as "let the people go so they may worship Adonai." Torah doesn't speak in terms of freedom for its own sake. Moshe seeks his people's freedom from servitude and oppression and hard labor -- and, it's not just about being freed from, it's also about being freed toward.

Pharaoh suggests he might let them go, but only the men, which Moses rejects: no, we're not leaving women and children behind. Then Pharaoh suggests he might let them go, but says they can't take herds or flocks with them. And Moshe says no, because:

וַאֲנַ֣חְנוּ לֹֽא־נֵדַ֗ע מַֽה־נַּעֲבֹד֙ אֶת־ה׳ עַד־בֹּאֵ֖נוּ שָֽׁמָּה / "We shall not know with what we are to serve until we get there."

On the surface, he's making a practical point. The request was to let our people go so that we could worship God in the wilderness, and the way we did that back then was through animal sacrifice. In the physical world, when he says "we shall not know with what we are to serve" he's talking about goats and sheep. But in the worlds of emotion and spirit, Moshe's highlighting a fundamental truth of every new undertaking: we never know what a journey will ask of us.

Going from slavery to freedom, from servitude to Pharaoh to service to the One, from narrow straits to liberation: it's the core story of Jewish peoplehood. We retell it every year at the Passover seder. We remind ourselves of it every Shabbat when we sing Mi Chamocha, and when we make the kiddush over wine. Those of us who have the practice of daily Jewish liturgical prayer remind ourselves of it every day.

It's also a core story of our lives. We move from constriction to expansion, from unconsciousness to consciousness, from calcified habits to transformation, over and over again. As we grow up and leave a childhood home for college, or leave the Purple Valley for the wide world outside. As we outgrow old circumstances and start over. As we discover that we can be more than we have been, and then pursue that becoming.

Hold that thought, because I want to pause and look at what it means to serve. I said earlier that Moshe's request is to free the people, but not so they can be accountable to no one. He seeks to free them from Pharaoh so they can serve God instead. That may sound like trading one master for another. But I think it's not, and here's why.

Pharaoh dehumanized us. He signed an executive order to have our baby boys murdered. Pharaoh believed that we were inferior to "regular" Egyptian citizens. Pharaoh saw us as teeming masses of foreigners, people who prayed differently and dressed differently and therefore deserved a lifetime of slavery in the pyramid-industrial complex. When describing how Pharaoh saw us, Torah says "the Israelites were fruitful and they swarmed" -- swarmed, like bugs. Being enslaved to Pharaoh meant working for the betterment of someone who saw us as equivalent to cockroaches.

Service to God is the opposite of that. To Pharaoh we were indistinguishable insects, but in God's eyes each of us is infinitely precious. Torah teaches that every human being is made in the image and the likeness of the One -- regardless of race or religion, shape or skin tone. To serve God means to serve the source of love and liberation. It means to choose to align ourselves with the force that brought us out of slavery, and to seek to break the shackles of those who are still enslaved.

But maybe you don't believe in God, not even the one I just described. That's okay. We can talk another time about why I'm more interested in engaging with -- talking to, wrestling with, demanding things of -- than believing in. No matter what you "believe in," there is service that awaits you, if you're willing to hear the call. Leave the world a better place than you found it. Work toward justice and human rights for all. Feed the hungry, protect the powerless, speak up for those who are victimized by structures of power and domination. That's the calling to which Judaism summons us.

And you won't know what resources you'll need for that work until you get there. You can learn. You can study. You can prepare with all your might. But the work of making the world a better place will require all of who you are, and you'll have to reach for strength and courage and conviction that you didn't know you had. Not once, but over and over again.

Every new chapter requires us to grow and deepen what we can offer to the world. It's true of a new semester. It's true of a new relationship, or a new job, or a new Presidential administration. We won't know with what we are called to serve until we get there. We won't know what this new adventure demands of us, what internal qualities of kindness or strength, courage or resolve we're going to need -- until we get there.

And "getting there" may be a misnomer. Because every moment asks us to dig deep and draw on the best of who we are. I know what resources I needed for yesterday, but yesterday's over. I know what resources I needed an hour ago, but that's then, and this is now. וַאֲנַ֣חְנוּ לֹֽא־נֵדַ֗ע מַֽה־נַּעֲבֹד֙ אֶת–ה׳ עַד־בֹּאֵ֖נוּ שָֽׁמָּה -- We won't know what this new moment asks of us until we reach it. And then there will be another new moment, and another after that.

Right now it's Shabbes, a deep dive into holy time. This is the time to soak up what nourishes us, to set aside the pressures of the week. This is the time to remember who we truly are -- not when we're defining ourselves through what we do, or what we've accomplished, or what's on our to-do list, but through who our hearts and souls yearn to be.

And when we emerge from this Shabbat, life will ask things of us. The new week will make demands on us. Our professors, or bosses, or families, will make demands on us. The world at large will make demands on us. May you be blessed with the ability to dig deep and find the reserves you need for whatever liberation, whatever new adventure, whatever challenges lie ahead. Shabbat shalom.

This is the d'var Torah I offered tonight at the Williams College Jewish Association. (I also offered a d'varling, a mini-d'var, during Kabbalat Shabbat services.)

An Extra Soul - a d'varling for Kabbalat Shabbat at WCJA

I've been thinking this week about the Torah of new beginnings. It's a new semester, a new beginning for all of you and all of your professors. And tonight marks a new beginning for me, too, the beginning of a new chapter for me at Williams. The poet Jason Shinder teaches, "Whatever gets in the way of the work, is the work." Whatever's on your mind can be the text you need to delve into, the lived Torah of your own human experience. What's been on my mind is new beginnings.

And hey, speaking of beginnings, every Friday night we sing a reminder of the creation story:

וְשָׁמְרוּ בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶת הַשַּׁבָּת, לַעֲשׂוֹֹת אֶת הַַשַּׁבָּת לְדֹרֹתָם בְּרִית עוֹֹלָם: בֵּינִי וּבֵין בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אוֹֹת הִיא לְעוֹֹלָם, כִּי שֵֽׁשֶׁת יָמִים עָשָׂה יְיָ אֶת הַשָּׁמַֽיִם וְאֶת הָאָֽרֶץ וּבַיּוֹֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי שָׁבַת וַיִנָּפַשׁ.

"The children of Israel shall keep Shabbat as an eternal covenant throughout the generations. Between Me and the children of Israel it is an eternal sign, (says God). For in six days, God made the heavens and the earth, and on the seventh day, God rested and was ensouled."

A lot of translations will say "God rested and was refreshed." But I think "was ensouled" is a better translation. When God rested on the seventh day, something happened to the divine Soul. God got more of a soul. God's soul unfolded more fully. Something about Shabbat increased God's soulfulness.

First there was a new beginning -- the ultimate new beginning, the creation! And then God rested and was ensouled. As exciting as new beginnings are, it's not good for us to keep moving forward at their high energy level and frantic pace. Torah's creation story comes to remind us that it's important to take a break.

One of my favorite teachings says that we too receive an extra helping of soul on Shabbat. On Friday night as we light the Shabbat candles, remembering in their twin flames the light of creation and the light of the burning bush, we too are "ensouled." We get a נשמח יתרה, an extra soul. (And tomorrow night when we make havdalah, we'll inhale spices as spiritual smelling salts, so we don't faint when our extra soul departs for the week.)

The beginning of the semester holds all kinds of promise, and all kinds of challenges. It's easy to get caught up in thinking about your classes, your papers or lab projects, all the deadlines marching off into the distance between now and the end of the year. But tonight offers us something different: an opportunity to let go of the work of creating -- even the work of planning to create.

Tonight we get to pause in our work of new beginnings, and be re-ensouled.

An invitation to try something. Put your feet on the floor. Take a deep breath, and imagine the breath filling you all the way up, and all the way down -- from the crown of your head to the tips of your toes. Let that breath go, and with it, let go of all of the week's stresses and frustrations. Set aside everything that worries you about the semester now beginning. Take another breath, and let it fill you all the way up again.

That's one way of glimpsing the extra helping of soul Shabbat offers us. Extra breath. Extra breathing room. Room for your heart to expand.

Another way the mystics see that extra soul is that it heightens our ability to yearn and to feel joy. The Hasidic master Reb Nachman of Breslov goes a step further and says the extra soul comes into being through our yearnings. Because we yearn, we get an extra soul during Shabbat. Yearning reveals who we most deeply are. What do you yearn for as this Shabbat begins? Get in touch with your yearnings, and your extra soul will unfurl.

May your Shabbat be soulful and sweet -- and enliven you for all the new beginnings, and all the future yearnings, to come.

This is the d'varling that I offered at the Williams College Jewish Association during Kabbalat Shabbat services. (I also offered a longer d'var Torah during dinner.)

Full circle: back to Friday night at Williams

I'm not sure when I first went to Friday night services and dinner at the JRC -- the Jewish Religious Center -- at Williams. But I'm pretty sure it was the first Friday of my freshman year, fall of 1992, a few months short of 25 years ago. College was new, and I wanted something familiar. Sure enough, davening the prayers of Kabbalat Shabbat was comforting, and WCJA (the Williams College Jewish Association) offered a way of meeting new people, and also there was a home-cooked dinner made by students in the JRC's kosher kitchen. I went back. And I went back again. Going to Shabbat at the JRC became part of my routine.

This week I'm returning to Friday nights at the JRC, now as the interim Jewish chaplain to the College. During my days at the College this week I've been re-acclimating myself to what used to be a familiar environment. Much of the campus is as it was when I was a student, though of course there are new buildings -- new structures in places that used to be open and empty, or new structures in place of old ones -- and new names to learn. What once was Baxter Hall (the student union building, home of mailboxes, a dining hall, a snack bar, and WCFM radio station, among other things) is now Paresky -- where my office is.

But the JRC feels much the same to me now as it did then. It's still a white, airy wedding cake of a structure, lined with bookshelves, art, and plush couches. Another thing that hasn't changed is that Friday night Kabbalat Shabbat services aren't led by the Jewish chaplain, but rather by students. This empowers the students to take their spiritual lives into their own hands instead of depending on a clergyperson to create spiritual and liturgical life for them. I remember how important that was to me when I was an undergrad, and I'm grateful that that tradition of student leadership hasn't changed in the intervening decades.

Returning now as staff to an institution where I was once a student is a fascinating experience. From this vantage I begin to see things about the whole institution that weren't obvious to me when I was immersed in it as a student. I'm also aware that I need to be careful not to superimpose my experiences from then over what today's students are experiencing now. I've been there a week, and already I can tell that the institution has changed in some interesting ways. Today there is a vibrant chaplaincy team working together to support the complex tapestry of multi-faith campus community life. That didn't exist 25 years ago.

But one thing that I suspect hasn't changed (much) is Friday nights at the JRC. Kabbalat Shabbat services are still student-led, just as they were then (though they're no longer using denominational prayerbooks -- now they use the Purple Valley Siddur, created just for use at WCJA.) Shabbat dinner is still planned, shopped-for, and prepared by students, just as it was then. I know that far more students come to dinner now than used to in my day. I'm looking forward to getting to know them, and to learning about each unique soul who chooses to infuse their weekend at this secular institution with a sense of Shabbat holiness.

In college my dear friend David (now Rabbi David, my ALEPH co-chair) wore a kippah every Friday night, even after leaving the JRC. He would wear his kippah all evening, walking back to his dorm, or going to whatever social opportunity presented itself after our time at the JRC. It was a consciousness-raiser for him, a way of reminding himself that it was a a time out of time, even after he had re-entered the flow of secular campus life. (I think of that even now, sometimes, when I wear my kippah in secular spaces.) I'm pretty sure that if he could see me at WCJA tonight, he would be pleased for me -- and for this community that I'm now blessed to serve.

January 29, 2017

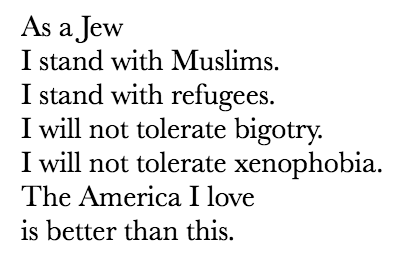

Outrage and heartbreak at Trump's #MuslimBan

I entered Shabbat and emerged from Shabbat heartsick at news of Trump's ban on Muslims and refugees entering this country. That he would issue such a ban at all is horrifying. That he did so on a day of remembrance of the wholesale slaughter of six million souls who were persecuted and killed for their religion (my religion) just makes this dystopian reality more surreal and more appalling.

Trump has suspended entry of all refugees into the United States for 120 days, barred Syrian refugees indefinitely, and blocked entry into this country for citizens of seven predominantly Muslim countries -- Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen -- for the next 90 days. His ban also blocks entry for green card holders from those countries.

There are already countless reports of permanent residents of this country held in airports across the country as they tried to return from funerals, travel, or study abroad, and family members of American citizens who sought to come here legally on family visas now facing immediate deportation. These are some of the instances we know about because they're making it into the media; surely there are other stories, equally heart-wrenching, that aren't known to us.

And the Syrian refugee crisis has been called the worst humanitarian crisis of our time. We should be responding to that crisis by welcoming refugees with open arms -- not, God forbid, closing our borders out of fear of people who look different, dress differently, or pray differently than we do.

Can you imagine escaping from wartorn Syria, living in a refugee camp for years, and finally making it through the red tape to be resettled here in a free country -- only to be turned away now by this? (That's exactly what happened to one family -- two parents and four children, one of whom is six years old. That child has been through hell I cannot imagine, and now that hell is prolonged.)

By the time I headed for bed on Saturday evening I was mildly heartened to see that a federal judge has blocked part of Trump's order -- but that's not enough.

In November, ALEPH was the first Jewish organization to insist that if the President requires Muslims to register, we will register with them. The Jewish people have living memory of being refugees barred from entry into nations (including this one) where our lives could have been saved. We of all people should be fighting this unconstitutional and unconscionable executive order with all our might.

This is not the America I want to live in.

The America I want to live in is one where religious freedom is uplifted and cherished -- not one where the person holding the highest office in the land demonizes adherents of any religion or people of any ethnicity.

The America I want to live in is one where refugees are welcomed and embraced -- not one where they risk being sent back to the horrors they fought so hard to escape.

The America I want to live in is a nation of opportunity and freedom -- not one where this kind of bigotry is allowed to stand.

The America I want to live in is the America of Emma Lazarus' poem The New Colossus:

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

The verse most often repeated in Torah is "love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt." The deepest wisdom of my religious tradition demands of us that we welcome refugees, not turn them away.

Torah demands that we love those who are different from us, not persecute them for their differences. My firmly-held principle of deep ecumenism reflects the truth that all religions are paths to the One, and my religious tradition calls me to stand firmly against bigotry and xenophobia in all of its forms.

I am outraged: as a rabbi, as the daughter and granddaughter of immigrants who fled the Holocaust to seek safety on these shores, as an American citizen, and as a human being. This policy is unconscionable. My nation must be better than this.

I donated to the American Civil Liberties Union and to T'ruah: the Rabbinic Call for Human Rights after Shabbat ended. Here's a list from HIAS (the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) of ways to help refugees. If you have suggestions of other actions we can take, I welcome them in comments.

It's a new week, friends, and we have work to do.

Although I cited, above, ALEPH's resolution urging all citizens to register as Muslims if the proposed Muslim registry were to come into being, I speak here as an individual, not as co-chair of ALEPH. I am also not speaking here for either of the institutions that employ me, the synagogue or the college. These views are my own.

January 28, 2017

How I sustain myself: Shabbat

A congregant asked me recently how I am managing. She meant both the circumstances of my life -- single parent, working one job and about to start a second -- and our national circumstances, as the new administration makes decisions that deeply distress me. What I really understood her to be asking was how I sustain myself during difficult times.

A congregant asked me recently how I am managing. She meant both the circumstances of my life -- single parent, working one job and about to start a second -- and our national circumstances, as the new administration makes decisions that deeply distress me. What I really understood her to be asking was how I sustain myself during difficult times.

One of my answers is Shabbat.

Every week we retell the creation story: for six days God labored creating the world, and on the seventh day God rested and was ensouled. We too can be ensouled, can experience an enlivening of our deepest selves, when we turn away from the world of work for 25 hours.

In some ways, the most sustaining Shabbatot are those I'm able to spend on retreat and/or with beloved hevre (rabbinic colleague-friends) because at those times I am able to truly set the world aside. There's no laundry or bills to ignore.

At those times I'm usually not leading davenen, and I can relax into the skilled hands of my colleagues, who I can trust to facilitate a spiritual journey through the liturgy. (If I am leading, I'm usually co-leading, which is its own kind of partnered dance and which gives me good "juice.")

At those times I can sink in to the rhythms of Shabbat in community with others who are attuned to those rhythms, from the high-spirited joy of welcoming the Sabbath bride to the full celebration of Shabbat morning to the poignant yearning of Shabbat afternoon as we prepare to bid farewell to our weekly "taste of the world to come."

But even Shabbatot when I am at home, "on duty" as rabbi and as mom, can be sustaining for me.

My Shabbat practices are sometimes idiosyncratic, and have shifted over the years, but here's one on which I am firm: I do not pay bills on Shabbes. If I open a bill on Friday afternoon and don't pay it by sundown, it waits on the desk until Sunday. It will still be there when Shabbat is over, and I need a day of respite from worrying about finances.

I also don't read the news on Shabbes. I give myself the gift of being able to look away from news media and political discourse for a day. This is good for me, maybe especially now. (Others have written about the importance of self-care in these times: see Mirah Curzer's How to stay #outraged without losing your mind.) Taking a day away from my own fury at the brokenness of our world strengthens me for the week to come.

In his book Jewish With Feeling, co-written with Joel Segel, Reb Zalman z"l (of blessed memory) wrote:

Save up for Shabbos those activities that pamper your soul. Here I would take a more lenient approach toward certain activities that traditional halakhah forbids, as long as they are done in the spirit of Shabbos. If you enjoy gardening for its own sake, rather than regard it as a chore you'd just as soon delegate to someone else; if you're enjoying spending time with your plants rather than working on a crop with which to feed your family, then gardening is a Shabbosdik activity for you. If you're a computer programmer by trade but a potter at heart, and if setting aside some Shabbos time each week would allow you to enjoy sitting down at the potter's wheel, then pottery is a Shabbosdik activity for you.

We might swear off the telephone during our Shabbos celebration -- nothing can introdude on a Shabbos like a telemarketing call! -- but have a special signal for family and friends (or simply use caller ID). A friend of mine used to have a telephone date on Shabbos aternoon with a woman he was engaged to, who lived in another city, and the first thing they'd discuss was their thoughts on the Torah portion of the week. The telephone becomes a sacred instrument when it allows us to do things like this.

Sometimes on Shabbes I cook a new recipe, something I've been wanting to try but haven't found time for. The traditional interpretations of the categories of "work" in which one does not engage on Shabbat would prohibit cooking on this day when we seek not to create change in the world but to find the gifts in what already is, but I've found that cooking something new can be restorative for me.

Sometimes on Shabbes I immerse in poetry -- whether writing or tinkering with my own poems, or the poems of others in which I can just luxuriate. Polishing the poems in Texts to the Holy, my collection of love poems to the Beloved, feels especially Shabbesdik to me these days -- but the simple fact of engaging with poetry can enliven my Shabbes.

Singing in harmony, when I can manage it, is an extra-special Shabbat treat. I'm an alto and some of my sweetest memories of the last many years of my life are of singing in harmony with others. When we are singing Jewish liturgy or psalms or Hebrew songs, that's even more true, but any singing at all can enrich the sense of connection that I look to Shabbat to help me access.

At the end of Shabbat I make havdalah. Sometimes that's bittersweet -- I can be reluctant to let go of the extra sense of connection with my soul and my Source that Shabbat can provide -- but I know that my Shabbat time will have strengthened my readiness to face the coming week... and I know it will come again, thank God, in six short days.

January 23, 2017

Light in the darkness

At the end of Shabbat, my son and I walked into the sanctuary of one of the synagogues in the bigger town south of here for a county-wide havdalah.

At the end of Shabbat, my son and I walked into the sanctuary of one of the synagogues in the bigger town south of here for a county-wide havdalah.

He immediately noticed the ner tamid -- the eternal light -- hanging on its chain in front of the ark where the Torah scrolls are kept.

(He compared it to something in an iPad game, because he is an ordinary seven-year-old boy, and animation is one of his frames of reference. This ner tamid is made of white glass shot through with lines of red, which made him think of digital fire. I couldn't find a picture of that particular ner tamid, so I'm illustrating this post with a different one. They come in many styles, and all are beautiful.)

"We have one of those at our synagogue too," I told him. "But ours is made of colored stained glass. Remember?"

"Oh yeah," he said. "I know what you're talking about."

"Every synagogue has one," I said. "It's supposed to always be on, all the time." And then I thought to ask him, "Why do you think that is?"

I don't know what I thought he would say. I was primed to give him a standard answer for why the ner tamid is there -- that it represents God's loving presence which is always with us. (To an adult, I might have also added that it represents the ancestral fire that Torah teaches was to be kept burning on the altar, not to go out.)

I should have known that he would have an answer of his own.

"To light our way through the darkness of our fears," he said confidently.

Now, maybe I primed him for that, the previous morning. We'd talked about people's hopes and fears upon the inauguration of a new President, and how he might hear something about those at the havdalah event on Saturday night.

But even if my mention of hopes and fears planted a seed for him, he made the leap from there to the ner tamid all on his own. He saw intuitively how our fears can feel like darkness, and how divine presence can be a beacon. It was obvious to him that the purpose of the ner tamid is to help us find our way when life feels dark.

"You just taught me something," I said to him. "Thank you."

"I did?" He seemed excited at the prospect. "Will you write it down?"

My child knows me well. "I will," I promised him.

And now I have.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers