Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 84

August 22, 2017

New in the Forward: an essay on midlife and Elul

I just wrote my first piece for Scribe at the Forward. It's about the work of midlife -- and the work of this time in the Jewish year. Here's a taste:

...Every life involves course corrections, and the midlife years are a ripe time for change.

For those of us who’ve had children, perhaps our children are old enough now that we can step back and think about something bigger than diapers and sleep deprivation. For those of us who’ve been partnered, this can be a time to look at whether our partnerships are sustaining us in body, heart, mind and soul. For those of us who care for aging parents, this can be a time to readjust the balance of responsibility to reflect current realities. For all of us, these years are a good time to say: are my choices working? Should the remaining decades of my life look like the previous ones? And if not, what do I need to shift?...

Read the whole thing: This Hebrew month, challenge yourself to look inward.

Support new Jewish poetry in 5778

I'm a longtime admirer of Ben Yehuda Press. They published Rabbi Jay Michaelson's The Gate of Tears, and Sue Swartz's we who desire, and Rabbi Shefa Gold's Torah Journeys, and they've recently brought out Jews Vs. Zombies. (No, really.) They also published my most recent volume of poetry, Open My Lips -- and will be publishing my next one, Texts to the Holy. And I've had the opportunity to read a couple of the other poetry volumes they'll be bringing out in the coming year, and oh, wow, are they fantastic.

They're doing a Kickstarter to support the publication of six volumes of new Jewish poetry in the year 5778 (that's 2017-2018, for those of you on the Gregorian calendar). Here's some of what they have to say about that:

People need poetry. Jewish people need Jewish poetry. Not only Jewish poetry, God forbid — we would never part with our Robert Frost or Wendell Berry or Mary Oliver or the rest of our shelf — but we also need poetry that expresses our specific culture and language. "Poetry," Frost wrote, "is what gets lost in translation." So too, translated yiddishkeit isn't quite the same. Hence, Jewish poetry. At Ben Yehuda Press, we publish poems (and other genres) whose Jewishness is integral.

Our Jewish umbrella casts a very wide shadow. Some of the poets we publish are intoxicated by God. Others look for spirituality in a world without God. Some allude to the Bible, others to Jewish experience. Ben Yehuda Press believes there is no one true Judaism, no one authentic Jewish voice. It is the multiplicity that defines our community, and our Judaism, and, optionally, our God.

With this Kickstarter campaign, Ben Yehuda Press is launching its poetry volumes for the Jewish year 5778. Immediately after Rosh Hashanah, we hope to publish three books of poetry. Three more volumes will be published in the spring.

These six titles come on the heels of the four we already published, starting with one volume in 2007, then three more in 2015. Now, with our ambitious line-up for 5778, we hope to begin a regular commitment to publishing Jewish poetry. But we need your help, to prove that there is a community of readers open to these new Jewish voices, and to help us grow that community.

I've donated toward this project, because as far as I'm concerned this is holy work that the world needs. (In the words of William Carlos Williams, "It is difficult to get the news from poems yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.")

Take a look at their Kickstarter, and if you can throw a few bucks toward the project, please do. Support the bringing of new Jewish poetry into the world!

August 13, 2017

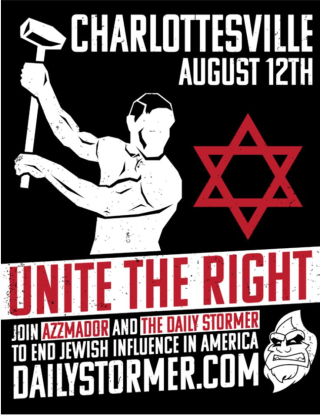

After Charlottesville

I spent Shabbat in an increasing state of horror about the white supremacist march in Charlottesville. Chants of "blood and soil," "white lives matter," and "Jew will not replace us;" white men carrying torches or wielding swastika-emblazoned flags; the death of a counter-protester at the hands of a maniac driving a car -- all of these led me to a heartspace of commingled grief and fury.

I spent Shabbat in an increasing state of horror about the white supremacist march in Charlottesville. Chants of "blood and soil," "white lives matter," and "Jew will not replace us;" white men carrying torches or wielding swastika-emblazoned flags; the death of a counter-protester at the hands of a maniac driving a car -- all of these led me to a heartspace of commingled grief and fury.

Watching this ugliness unfold was not a "Shabbesdik" (Shabbat-appropriate) way to spend a day when we're meant to live as if the world were already redeemed. Ordinarily I ignore the news on Shabbes, and seek to inhabit a different kind of holy time. But it felt important to bear witness, both to the white supremacist protests that blended the KKK with Nazism, and to those who bravely stood up to offer a counter-message.

Throughout the day I sought strength and hope in the fact of rabbis who traveled to Charlottesville to stand against bigotry alongside clergy of many faiths, "praying with their feet," as it were. I took comfort in the number of people I saw donating to progressive causes in Charlottesville (per Sara Benincasa's suggestion). But the weekend made clear just how much work we have to do to root out the cancers of racism and prejudice in this country.

Bigotry and xenophobia are among humanity's worst impulses. White supremacy and antisemitism are two particularly ugly manifestations of those impulses (and they're clearly intertwined -- I recommend Eric Ward's essay Skin in the game: how antisemitism animates white nationalism, which is long but is deeply worth reading). After Charlottesville, I recognize that there is far more hatred than I knew.

I was appalled by the ugliness we witnessed this weekend, and I know that's a sign of my privilege. I haven't had to face structural racism. I imagined that modern-day Nazis were laughable, and that the moral arc of my nation would bend toward justice without my active assistance. No longer. These hatreds are real, and alive, and playing out even now. They will not go away on their own.

The work ahead is long, but we must not give up. We have to build a better nation than this: more just, more righteous, concerned with the needs of the immigrant and the refugee, cherishing our differences of origin and appearance, upholding the rights of every human being to thrive regardless of race or religion or gender expression, cherishing every human being as made in the image of the Infinite One.

In offering that core Jewish teaching, I don't mean to parrot the "all lives matter" rhetoric that erases the realities of structural racism. Every human being is made in the divine image. That doesn't change the fact that in today's America, we don't all have equal opportunities or receive equal treatment. In today's America, racism is virulent. So are other forms of bigotry and hatred. We have to change that.

We have to mobilize, and educate, and hold elected officials accountable, and combat voter suppression, and give hatred no quarter. Those of us who are white have to work against racism and the malignant rhetoric of white supremacy. We have to combat antisemitism in all of its forms. We have to recognize that all forms of oppression are inevitably intertwined, and we need to work to disentangle them all.

This is a marathon, not a sprint. We won't all be able to participate in this holy work in the same ways. Some will be able (for reasons of gender or skin color or finances) to put their bodies on the line in direct action and protest. Others will participate by calling congresspeople, running for office, writing op-eds, or teaching children how to be better than this. But it's incumbent on all of us to do what we can.

I've often heard people muse aloud that we wonder how we would have reacted if we'd been alive during the Shoah, or the Civil Rights years, or any number of other flashpoint times of crisis and injustice. Would we have protected the vulnerable? Would we have spoken out? Would we have been upstanders? This is a time of crisis and injustice, and the only unacceptable response is doing nothing at all.

Some links:

Showing Up For Racial Justice

How to fight white supremacy in Charlottesville and beyond

Former Neo-Nazi Says It’s On White People To Fight White Supremacy

Five ways to fight back against antisemitism

How Jews can fight white supremacy in Trump's America

A call to my beloved Jews: we gotta talk about privilege

My Family is Black and Jewish. Here's what Charlottesville means to me.

Hate in Charlottesville: the Day the Nazi Called Me Shlomo

Ten Ways to Fight Hate: a Community Response Guide

Cross-posted, with some additional framing material, to my From the Rabbi blog.

August 11, 2017

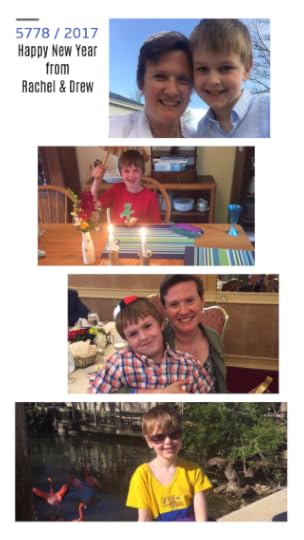

Elul Poem 5777 / New Year's Card 5778

God says: face facts. The old year

God says: face facts. The old year

is ending. You’ve outgrown it.

The flowerpot that used to be home

isn’t big enough anymore. Once

it was spacious. Now your roots

push uncomfortably against the walls.

It's time to stop contorting yourself

to fit inside a story that's too small

for who you can become. God whacks

the bottom of your pot, sends you flying.

Once you're pried from the old year

your roots will ache, shocked

by open air. You'll wonder whether

you could have stopped growing.

But one morning you'll wake, realize

you've stretched in ways you never knew

you hadn't done before. The sun

will feel like a benediction, like

grace. You can't help turning

and re-turning toward the light,

toward becoming. And wait 'til you see

what dazzling flowers you'll discover

springing from your fingertips:

your life renewed, beginning again.

שנה טובה תכתבו ותחתמו

May you be written & sealed for a good year to come!

For those who are so inclined: here are my annual Elul / High Holiday card poems from 2003 until now.

August 10, 2017

Eat, be satisfied, and bless - a d'var Torah for Eikev

I was working a few days ago with a friend's daughter who's becoming bat mitzvah in a few weeks. I found myself remembering a moment shortly after my own celebration of bat mitzvah.

I was working a few days ago with a friend's daughter who's becoming bat mitzvah in a few weeks. I found myself remembering a moment shortly after my own celebration of bat mitzvah.

Faced with the prospect of writing a mountain of thank-you notes. I took up my pretty new stationery and I wrote, "Dear so-and-so, thank you for the gift, love Rachel" over and over and over.

When my mother found out that I hadn't been personalizing the notes, she made me throw them all out and start again. She insisted that I say what each gift was and why I appreciated it.

And that's how I learned that one must be specific in a thank-you note. "Thank you for the thing, whatever it was" will not cut it. (Not for my mother, anyway.) Enter this week's Torah portion, Eikev:

וְאָכַלְתָּ֖ וְשָׂבָ֑עְתָּ וּבֵֽרַכְתָּ֙ אֶת־יָה אֱלֹהֶ֔יךָ עַל־הָאָ֥רֶץ הַטֹּבָ֖ה אֲשֶׁ֥ר נָֽתַן־לָֽךְ

And you shall eat, and you shall be satisfied, and you shall bless YHVH your God for this good land that God has given you.

From this springs the custom of birkat hamazon, the "grace after meals," also called bentsching. Our tradition teaches us to offer that prayer after any meal at which bread is consumed in a quantity as large as an olive. Even for a bite-sized gift, we're meant to say thank You.

The traditional birkat hamazon contains four blessings: for the food, for the land, for the holy city of Jerusalem, and for God's goodness. Those blessings are adorned with an introductory psalm and a series of blessings that call God The Merciful One, plus additions for Shabbat and festivals. This is how our tradition works: a short text is embroidered with additions, and the additions become canon too.

And while it's easy to roll our eyes at that process of accretion -- this is how we wind up with long prayers: because we get attached to the new additions, but we can't bear to get rid of the original material! -- the process often yields liturgy that I truly love singing. And I do love bentsching (singing the birkat hamazon) when I'm lucky enough to gather a table of people who want to sing it with me.

Besides, one could argue that the impulse comes out of the same place as my mother's decision to make me rewrite all of my thank-you notes. It's not enough to just say "Hey, thanks for the thing." If we're doing it right, we ought to articulate gratitude for the food, and for the land in which the food arises, and for our holy places, and for the goodness of God that leads to the gift of sustenance in the first place.

Then again, it's often our custom here to sing abbreviated liturgy. This is true in its most concentrated form when we have contemplative services. But most of the time we opt for fewer words and greater connection with those words, rather than singing the full text of what the most liturgical versions of Judaism might prescribe. Most often when we bless after a meal here, we sing brich rachamana:

בּרִיךְ רָחָמַנָה מָלְכַא דְעָלמַע מָרֵי דְהָאי פִתָא.

You are the source of life for all that is and Your blessing flows through me.

(Aramic translation: Blessed is the Merciful One, Sovereign of all worlds, source of this food.)

You have probably heard me say that that blessing originates in Talmud. You may also have heard me say that it's the shortest possible grace after meals that one can offer -- for instance, if one were being chased by robbers and needed to make the prayer quick. This is a popular teaching, though I can't actually source it! But it shows awareness, in the tradition, that sometimes we can't manage full-text.

For me, then, the question becomes: how do we sing the one-liner in such a way that we invest it with the kavvanah (the meaning and the intention) that the long version is designed to help us cultivate? How do we sing the short version without falling into the trap that I fell into as an overeager thirteen-year-old writing "thanks for the thing"?

One answer is to go deep into the words. This short Aramaic sentence tells us four things about God: God is blessed, and merciful, and is malkah, and is the source of our sustenance. I want to explore each of those, but I'm going to save the untranslated one for last.

1) God is blessed. What makes God blessed? We do, with our words of blessing. We declare God to be blessed, and by saying it, we make it so. (If this intrigues you, read Rabbi Marcia Prager's The Path of Blessing -- it's in our shul library.)

2) God is merciful. The Hebrew word "merciful" is related to the Hebrew word for "womb." God is the One in Whose Womb all of creation is sustained. When I really think about that metaphor, it blows my mind. The entire universe is drinking from God's umbilical cord!

3) God is the source. The source of all things; the source of every subatomic particle in the universe; the source of the earth in which our food comes to be, and the hands that raised or harvested or prepared what we eat, and the source of the things we eat that sustain us.

4) And God is malkah. That word can be translated as King, or Queen, or if you prefer gender-neutral, Sovereign. But to our mystics, the root מ/ל/כ connotes Shechinah: the immanent, indwelling, feminine Presence of God -- divinity with us, within us, among us.

God is blessed because we invest our hearts and souls in speaking that truth into being. God is mercy made manifest in our lives. God is the source from Whom all blessings flow. And God is that Presence that we feel in our hearts and in our minds, in our souls and in our bones. It's that Presence -- or, if you'll permit me some rabbinic-style wordplay, those Presents -- for which we articulate our thanks.

To be really grateful is to be grateful for the specific, not the general. (That was my mother's thank-you note lesson all those years ago.) The Aramaic says 'd'hai pita,' "for this bread," not just for bread. I'm grateful for this bread that I took into my body. That makes it personal, because gratitude is personal by definition. If we don't take our gratitude personally, then it's not gratitude; it's just rote words.

Our task is to eat, because ours is not an ascetic tradition. To be satisfied, because that is a healthy response to consumption. (Alexander Massey suggests that we cultivate satisfaction as a good in itself, and pray from there.) And then our task is to bless, and to really feel the awareness and the gratitude and the presence, to take them personally and make them real -- no matter what words we use.

Image source: a challah cover bearing the words "you shall eat, and be satisfied, and bless," available at one of my favorite Judaica stores, The Aesthetic Sense. Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.

August 7, 2017

A very special New York City Shabbat

This coming weekend I'll be in New York city for two very different and very special Shabbat experiences.

The first is Shabbat By the Sea with Temple Beth-El of City Island. You can read about it in the TBE newsletter. The short version is: 7pm on Friday night at the home of TBE members Ken and Steve Binder, 2 Bay Street on City Island. (If it rains, we'll meet at the shul instead.) I was blessed to be present for Shabbat by the Sea last year (here's their post about it) and it was a highlight of my summer. I can't wait to return and to dance in my Shabbes whites with TBE friends as we welcome Shabbat by the water's edge. There's nothing else like it.

The second is a Shabbat In The Garden adventure co-sponsored by TBE of City Island and by another Jewish Renewal community called Shtiebl, which will take place starting at 9:45am on Saturday at the New York Botanical Garden (meet inside the main gate, 2900 Southern Blvd). I'll be co-leading a contemplative morning Shabbat service with my friends Rabbi Ben Newman of Shtiebl and Rabbi David Markus of TBE. (Here's the Facebook event where you can RSVP; wear walking shoes and dress for the weather.)

The first time I came to City Island I was delighted and surprised. It feels entirely unlike what I associate with the phrase "New York City" (or "The Bronx"), which just goes to show that New York is vast and contains multitudes and is perennially surprising, maybe especially to outsiders like me. (Though I get the sense even some lifelong denizens of the Five Boroughs don't know City Island either.) I've never been to the New York Botanical Gardens but I'm guessing I will find them equally beautiful.

The coming Shabbat is a special one. It's called Shabbat Mevarchim Elul, the Shabbat immediately preceding the start of a new lunar month -- in this case, the lunar month of Elul, the month that leads directly to the Days of Awe. The name Elul can be read as an acronym for the phrase "I am my beloved's and my beloved is mine" -- a quote from Song of Songs that can be understood as an expression of love between human beloveds, and as an expression of love between us and the Divine.

Join us by the water's edge and in the garden of Shabbat. (And in the garden on Shabbat!) Let intimate encounter with the Divine be the updraft that lifts you into heightened readiness to prepare for the High Holidays. Join us as we savor high summer in two of New York City's most beautiful places. Join us as we seek the Face of the Beloved through song, dance, contemplation, and just plain being. I look forward to seeing you there.

August 2, 2017

49 days until Rosh Hashanah

There are seven weeks between Tisha b'Av and Rosh Hashanah. Forty-nine days between the spiritual low point of our year, and the newest of new beginnings.

There are seven weeks between Tisha b'Av and Rosh Hashanah. Forty-nine days between the spiritual low point of our year, and the newest of new beginnings.

Reb Zalman z"l taught that these 49 days parallel the 49 days of the Omer between Pesach and Shavuot. And Rabbi David Markus this year gave me a way to see how the parallel extends too to the themes of those two great festivals, which we now recapitulate in reverse. In the spring we move from liberation (Pesach) to revelation (Shavuot). As summer prepares to turn, he writes:

Tisha b'Av focuses us on what's buried in darkness (revelation), and in seven weeks Rosh Hashanah will open wide the teshuvah gates of spiritual renewal (liberation). Our summer/fall journey is our spring journey in reverse: we return to our beginnings.

During the Omer count, many of us focus on seven qualities that we and God share. Sometimes we call these middot, character-qualities. Sometimes we call them the seven "lower" sefirot, the spheres or realms or channels through which divinity flows and is modulated into different forms. As white light is revealed through a prism to contain all of the colors of the rainbow, so God's Oneness is revealed through this prism to contain these seven colors, these seven qualities, in which we too partake.

During the Omer count, we begin with a week of chesed, lovingkindness, and then work our way all the way to malchut (Shechinah, immanent divine Presence.) During this reverse count we begin with a week of Shechinah / malchut, and then work our way back "up the ladder" to chesed / love. (Here's a brief description of these seven qualities from R' Laura Duhan Kaplan, here's another way of thinking about them from Iyyun, and R' Simon Jacobson describes them in emotional terms.)

Tisha b'Av was Monday night and Tuesday. Now we've entered the first of the seven weeks between Tisha b'Av and the Days of Awe. This is our week of malchut: immanent, indwelling divine Presence. God with us, within us, among us. The divine feminine, the Shechinah. This is also the first of the seven weeks of consolation (see The Seven Weeks of Comfort.) After facing brokenness on Tisha b'Av, now we open ourselves to healing, to comfort, to balm for our wounded places as the Days of Awe approach.

Through a four-worlds lens, I'm asking myself: what do I need to do this week in order to begin preparing myself for Rosh Hashanah? What do I need to cultivate in my heart of hearts, what do I need to feel? What do I need to ruminate and reflect on? What would best feed my soul and uplift my spirit?What do I need -- what do you need; what do we all need -- to do and feel and think and be during these next 49 days in order to reach the new year with a whole and open heart, ready to be transformed?

Cross-posted to my congregational From the Rabbi blog.

July 26, 2017

Balancing joy with sorrow: a d'var Torah for Shabbat Shachor

It's Shabbat Shachor, the "Black Shabbat" that falls right before Tisha b'Av. Today our experience of the sweetness of Shabbat is tempered by awareness of what's broken, from our own ancient stories of destruction and becoming refugees to what we see and hear on the news even now.

It's Shabbat Shachor, the "Black Shabbat" that falls right before Tisha b'Av. Today our experience of the sweetness of Shabbat is tempered by awareness of what's broken, from our own ancient stories of destruction and becoming refugees to what we see and hear on the news even now.

Monday night will bring Tisha b'Av, when we'll go deep into this brokenness -- a paradoxical beginning to the uplifting journey toward the Days of Awe. In Hasidic language, that's a descent for the sake of ascent.

But how can we now celebrate Shabbat with awareness of these sorrows?

You might ask the same question of anyone whose loved one has received a fearful diagnosis, or of any mourner, or of anyone who knows the grief of ending a marriage or losing a beloved home or enduring any kind of loss.

In Jewish tradition, we suspend formal mourning on Shabbat and festivals. But someone who is grieving is likely to still feel their grief even on days that are supposed to be joyful -- maybe especially then, because the disjunction between how they are "supposed" to feel and how their hearts naturally flow can be so profound.

Shabbat Shachor offers us an opportunity to sit with that tension between joy and grief. For many of us, that's deeply uncomfortable. It's easier to paper over the sorrow and just be happy, or to keep joy at arm's-length and just sit with sorrow. Today our tradition asks us to resist both of those easy outs, and to sit with the dissonance of a psycho-spiritual chord that's both major and minor.

If you're feeling grief, today invites you to temper your sadness with Shabbat joy. If you're feeling Shabbat joy, today invites you to temper your happiness with an awareness of life's sorrows. This can feel like a grinding of our emotional gears. The heart wants to lurch to one extreme or the other -- sorrow or joy -- not to stretch wide enough to feel them both at the same time. Resist that temptation.

On Monday night we'll be wholly in a minor key. Tisha b'Av is a day of mourning for our communal losses: the destruction of the first Temple by Babylon, which led to our becoming refugees; the destruction of the second Temple by Rome; and a long list of other losses and griefs throughout our history. That day isn't quite here, but we can feel it just around the corner. We can see it coming.

I've learned as a pastoral caregiver that every loss evokes and activates every other loss. Sitting with our historical and communal losses can heighten our sadness around personal losses: the loss of a loved one, the loss of a job or a home, the loss of a relationship, the loss of health, the loss of hope. Maybe you're feeling that way today. If not, you've likely felt that way before... and will feel that way again.

And yet amidst all of that loss, both present and anticipated, today we're still called to open our hearts to the abundance and flow of Shabbat. On Shabbes we're still invited to taste perfection. Even if our ability to rejoice is subdued by circumstance or memory, we still offer thanks today for life's many blessings. We still open ourselves to the experience of feeling accompanied and cradled by divine Presence.

It's not a matter of either / or -- either we savor the sweetness of Shabbes, or we marinate in the bitterness of grief. It's a more nuanced and complicated both / and. On Shabbat Shachor we affirm that our hearts are flexible enough to hold both. And what we affirm today as a community carves pathways in our hearts that will help us affirm this truth in our own ways, on our own time, throughout our lives.

Today is our communal Shabbat Shachor, the day when we sit with this balance between grief and joy as a community. But in every life there are individual Shabbatot that take place in this middle ground, partaking in sweetness and in loss. Today reminds us that even when we grieve, Shabbat can still bring comfort -- and that even at our times of greatest joy, some of us will still struggle with sorrow.

Today invites us to cultivate compassion for ourselves and for each other, knowing that everyone lives in the balance, the tension, the middle ground between sorrow and joy. This is spiritual life. This is human life. May we recognize that even at times of rejoicing, we and our loved ones may be carrying grief...and may we help each other access gratitude and joy even during life's times of darkness.

Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.

Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg's Nurture the Wow

Somewhere in my first year or two of parenthood, it dawned on me -- through the haze of fatigue, laundry, diapers, and tantrums (Yonatan's and mine both) -- that I actually had access to a treasure trove of wisdom that could help me do the exhausting, frustrating, challenging work of loving and raising my kid. It took me a while to realize it, though, because how I was changing as a mom seemed to be taking me away from my tradition's ideas about what spiritual practice is supposed to be. It had been panic-inducing for some time there, honestly, feeling like I was on a boat that was drifting, slowly, from the island on which I'd made my home for almost fifteen years.

And yet, when I looked more closely, I realized that the treasures that had sustained me for so long could nourish me through this new, hard, bewildering thing. In fact, the Jewish tradition (as well as other religious traditions that I'd studied, even if I didn't live as intimately with them) can actually illuminate the work of parenting -- the love, the drudgery, the exasperation, all of it.

That's from the first chapter of Nurture the Wow by Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, and it is as good an encapsulation of this beautiful, thoughtful, necessary book as any review I could write. (You'll also find a good encapsulation in the subtitle: Finding Spirituality in the Frustration, Boredom, Tears, Poop, Desperation, Wonder, and Radical Amazement of Parenting.)

From what I just quoted, R' Danya continues:

This fact isn't necessarily intuitive, though, because, let's face it, for thousands of years, books on Jewish law and lore were written by men, mostly talking to other men. These guys were, by and large, not engaged in the intimate care of small children. Somewhere else, far from the house of study, other people -- women, mothers -- were wrangling tantrumy toddlers and explaining to six-year-olds that they really did have to eat what was on their plate. At least, I assume that was what was happening -- again, for most of history, the people who were raising children weren't writing books, so we don't totally know.

This means a few things. This means that a lot of the dazzling ideas found in our sacred texts about how to be a person -- how to fully experience awe and wonder; how to navigate hard, painful feelings; how service to others fits into the larger, transcendent picture -- was never really explicitly connected to the work of parenting. It just didn't occur to the guys building, say, entire theological worldviews around love and relationships to extend their ideas to the kinder -- probably because the work of raising children just wasn't on their radar screen.

Oh, holy wow, do I wish this book had existed when my son was born seven and a half years ago!

Those of y'all who were reading my blog during my early years of parenthood may remember my struggles with exactly these issues. At the very beginning I was too caught-up in postpartum depression (which I eventually wrote about for Zeek). But as the months went on and my PPD was treated, I still chafed against the sense that my beloved religious system seemed to presume that someone else was taking care of the baby so that the (male) person with a spiritual life could adequately pray (see Privilege, prayer, parenthood.)

R' Danya gets all of that -- intimately, and on every level -- because like me, she was an ardent and engaged Jew before she became a mom. Like me, she had a strong Jewish identity and strong Jewish practice that was rooted in her pre-child life. And then everything turned upside-down, and she did the impossibly hard work of wrestling with the dual angels of parenthood and religious tradition to figure out how to wrest a blessing not from one or the other but from both of them together.

Reading this book, I kept grabbing my pen to underline and make exclamation points in the margins. It's clear to the reader that R' Danya has a deep love of Jewish tradition and spiritual practice, and she also loves her children and the ways in which being a mom has expanded her capacity for growth and care, and she is not willing to cede either one of those loves. Instead she insists not only that they can inform each other, but that they must -- and that when they do, the rewards are rich and profound.

She writes beautifully about coping mechanisms and chosen family. ("Sometimes it's just about feeling like you're not stranded on an island, but rather sitting at the edge of a beach full of love and laughter and people who are a regular part of your life and adore your kid nearly as much as you do.") She writes beautifully about the covenant we as parents make with our children, and how easy it is to see the Biblical children of Israel as overtired toddlers who need a nap. (I wrote that in a d'var Torah once.)

She writes beautifully about how parenthood can teach us the importance of sacred play... ("Entering into play requires giving ourselves permission...for the game not to be played perfectly and for the money piles to get messed up, permission to be a fool, permission to let it be OK if we get to the bath a few minutes later today.") ... and about what we do spiritually with the inevitable boredom of parenting, because how we work with that boredom impacts the kind of parents or caregivers we aim to be.

For me the most powerful parts of the book are where R' Danya is writing explicitly about the tensions between parenthood and spiritual practice as defined by normative (male) Jewish tradition, and where she's writing explicitly about the challenges of being a female parent in particular and navigating parenthood alongside what society tells us about who and how women are supposed to be. Citing Luce Irigaray (whose work I remember reading for the first time as a religion major some 25 years ago), R' Danya writes:

When Irigaray said, "The path of renunciation described by certain mystics is women's daily lot," she was being sarcastic. Male mystics made a fuss about giving up freedoms and serving humbly because, for them, it was a countercultural move that produced radical effects. For women, it was just business as usual.

So where does that leave those of us who parent while female? Where does that leave our ego, our sense of selfhood, our real, actual love for our kids, our perhaps sometimes desperate desire to get out there in the world and, you know, do taxes or something, anything to reclaim our sense of being someone other than Mommy? What does it mean for our ego -- and our spiritual potential -- when we enter the crucible of self-sacrifice that is motherhood?

R' Danya's answer is deep, and radical, and resonates with me powerfully: that as some of us who are mothers discover, "our acts of selflessness can actually bolster the self, in a deep authentic way." The Jewish mystical tradition talks about bittul ha-yesh, often translated as "annihilating the self," though Reb Zalman z"l preferred the translation "becoming transparent." That's the kind of bittul I understand R' Danya to mean. Sometimes parenthood can teach us to become transparent conduits for a light and a love that comes from beyond us but also enlivens us and makes us more deeply who we really are.

And she goes on to say the following, about being truly seen:

I don't know about you, but there are a few people in particular in my life... who I feel really, actually see me. And when I'm with one or more of these people, I feel able to be the best, brightest, shiniest version of myself. And at the same time, these are the people who kick my butt, both explicitly and not, to be better than I am... Giving just feels different when it's offered from a rooted place of selfhood and connection.

And with my kids, well, more than anyone else they force me to really see myself.

I know what she means about those people in my life who really, actually see me. I know what it's like to feel pulled and pushed and inspired into being the best me I can be, because in their eyes I am already that person (or at least I have the capacity to be that person), and being seen as my best self helps me to live into what those loving eyes see in me. And when I apply that frame to the way I think about relating to my kid, and the way my kid sees me, my whole sense of myself comes into a different kind of focus.

Toward the end of the book, she writes:

Our growth in this spiritual practice of loving and caring for our children isn't always linear. It's most certainly a "practice" in the true sense of the word -- something we try, again and again and again, sometimes hitting the right notes and sometimes not quite getting there.

Yes indeed. But the great thing about a practice is that the more one does it, the deeper one can go, and the more thoroughly the practice and the experience of the practice can transform the one who is doing the practicing.

I'm grateful to R' Danya for writing this book, and I recommend it highly to anyone who's interested in parenthood or caregiving and in the life of the spirit, whatever form your spiritual life takes.

July 24, 2017

Breathing space

To be fully alive and fully human, we need space, or room to breathe. This need is fundamental: it is rooted in our everyday experience. We all know what it is like to feel crowded, pressed, or overwhelmed. We know what it is to face deadlines, expectations, demands. We know these pressures can originate from outside us as well as from within us. And we know the relief, release, and freedom that come from outer and inner space -- room to breathe and to be ourselves. We owe it to ourselves, individually and communally, to find such room, such space.

Those words come from Father Philip Carter, in his essay "Spiritual Direction as an 'Exchange of Gifts'," in the March 2017 issue of Presence: an International Journal of Spiritual Direction. From time to time I pick up back copies of that magazine and leaf through them, and often I find that an idea or a quotation leaps off the page and demands my attention. Today it was Carter's words that grabbed me.

"To be fully alive and fully human, we need space, or room to breathe..."

Shabbat is supposed to offer precisely that breathing room: one day of the week during which we can let go of our to-do lists and obligations, a day when we can focus on being rather than doing. Of course, that breathing room can be hard to come by -- especially for those who dedicate their days to caring for young children or aging parents, for whom Shabbat may not offer a genuine respite of any kind.

But this isn't just about our obligations. Even someone with a daily to-do list the length of my arm can still seek the internal and spiritual spaciousness that allows them to draw a full breath. This is the space the soul really requires: space to grow, space to change, the space of the freedom to become and in so doing to discern what would bring joy. Our souls need these things the way our bodies need air.

And without room to breathe, the soul can't flourish. Without space to grow, and maybe more importantly space to just be, the spark of divinity that enlivens us flickers and dims. A soul that is constantly constrained will be damaged by that constriction, in the psycho-spiritual equivalent of the maiming once experienced by women who endured having their feet bound and reshaped.

There are all kinds of circumstances that create constriction. Some of them are internal: grief, or depression, or personal struggles. Some are external: emotionally and spiritually abusive workplaces, or family relationships, or systems of oppression. The challenge lies in not internalizing the messages that tell us we either don't need to draw a full breath (spiritually speaking)... or, worse, don't deserve to.

You deserve to draw a full breath. You deserve to have room to breathe. You deserve to change and grow. You deserve to take up space in the world. You deserve to be honored, and valued, and treated like the precious soul that you are. Anyone in your world who tells you otherwise does not have your best interests at heart, and they have a vested interest in keeping you small, and they are wrong.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers