Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 82

October 24, 2017

On Avram and Sarai and #MeToo

This d'var Torah mentions mistreatment of women, including sexual assault. If this is likely to be triggering for you, please exercise self-care.

This week's Torah portion is rich and deep. It begins with God's command to Avram לך–לך / lech-lecha, go you forth -- or, some say, go into yourself. It contains God blessing Avram. It contains, too, the birth of Ishmael to Avram through Hagar, which we just read on the first day of Rosh Hashanah.

This week's Torah portion is rich and deep. It begins with God's command to Avram לך–לך / lech-lecha, go you forth -- or, some say, go into yourself. It contains God blessing Avram. It contains, too, the birth of Ishmael to Avram through Hagar, which we just read on the first day of Rosh Hashanah.

But reading it this year, I was struck by a passage I've always glossed over: the part where Avram and Sarai go into Egypt, and Avram says to her, "You're beautiful, and if they think you're my wife they'll kill me and take you -- so pretend to be my sister instead." And Pharaoh takes Sarai as a wife.

Avram benefits greatly from this deception: he acquires "sheep, oxen, asses, male and female slaves, she-asses, and camels." Meanwhile, Pharaoh is punished for sleeping with Sarai. God brings plagues on him and his household, until he comes to Avram and says, "Why didn't you tell me she was your wife?! Take her back!"

Perhaps predictably, the text says nothing about what all of this was like for Sarai. She has been asked to lie about her identity to protect her husband. Also to protect her husband, she allows herself to be taken into Pharaoh's court. She gives Pharaoh access to her body. Torah tells us nothing about how she felt, but I think I can imagine.

I don't want this to be in our Torah -- our Torah that I cherish and teach and love. But on the matter of women's rights and women's bodies and women's integrity, our Torah here is painfully silent. It may not explicitly approve women being treated as property, but neither does it explicitly disapprove.

Or: neither does it explicitly disapprove here. As we move from right to left through our scroll, Torah changes. Genesis contains this story, and the story of Dinah, raped by Shechem, who then seeks to wed her. Like Sarai in this passage, Dinah has no voice and no apparent agency.

But by the time we get to Numbers, Torah gives us the daughters of Tzelophechad, a surprisingly feminist narrative that gives women both voice and power. We can understand this dissonance from a historical-critical perspective as the weaving together of texts from different time periods. From a spiritual perspective, we can see this as the Torah herself evolving.

Torah reflects a trajectory of growth and progress: on humanity's part, and arguably even on God's part. But this moment in our ancestral story is distressingly patriarchal. It reminds me that the word "patriarchal" comes to us from our relationship with these very forefathers, who weren't always ethical in the ways we may want them to have been.

This year I read these verses juxtaposed against the #MeToo movement that unfolded in recent weeks on social media: woman after woman after woman saying, harassment and misogyny and sexual assault and sexual abuse and rape are all part of a whole, and I too have been a victim of these proprietary and predatory behaviors.

Maybe Sarai chose to pretend for Avram's sake. We don't know; Torah doesn't say. Maybe she was willing to allow herself to be raped to protect her husband. I can imagine situations in which I would allow myself to be violated to protect someone whom I love. But that is not a choice any woman should ever have to make.

I read recently about an exercise that Jackson Katz did in a mixed-gender classroom. He asked the men, what do you do to protect yourselves from being raped? And there was silence, and uncomfortable laughter, and eventually one of the men said, I don't do anything; I've never really thought about it.

And then they asked the women, and the women generated a long list without even trying. I don't walk alone. I don't go out at night. I don't park in dark places. I make sure I keep my drink in sight so no one can slip a roofie into it. I carry mace. I don't wear certain clothes. I don't make eye contact with men...

Most of us don't even think about these things: not the men, who have the privilege of not having to worry about being treated as property, and not the women, who do these things almost unconsciously. Sexual harassment, assault, and violence against women are the water we swim in, the air we breathe.

Reading this story in Torah makes my heart hurt. I don't want Avraham Avinu, our patriarch, to have behaved this way toward Sarai. But he did, and in the context of the time it was unremarkable. Notice how everyone assumed Sarai was going to get raped no matter what. That's the assumption when women's bodies are property.

Guess what: it's still unremarkable. This is what patriarchy is, what patriarchy does: it allows men's need to have sex, or to feel powerful, to trump the needs of women to have bodily integrity or to be whole human beings. Patriarchy is still real, and it is still damaging us. All of us. Of every gender.

Here are some things we can do to be better than this:

Listen to women. (Here's a good essay about how exactly to do that.) Sarai doesn't have a voice in this story: don't replicate that today by not listening to women. Listen to us and believe us. When a woman says she was assaulted or violated, believe her.

Don't say "but men get raped too." Yes, they do, and that is terrible, and don't derail the conversation to make it about men right now. Patriarchy is a system that centers the needs and perspectives of men over the needs and perspectives of women, in every way. Make the radical choice not to perpetuate that.

If you're sexually active, keep active consent as your guiding light, and teach your children the importance of active consent too. If someone's not enthusiastic, stop. If someone says no -- or "not right now" -- even if they say it through body language instead of words -- then don't do it. Whatever it is. Because no one ever is entitled to someone else's body.

Understand that men feeling entitled to women's bodies takes a million different forms: from harassment, to the way men talk to women or talk about women, to the way men look at women (and the way women are depicted in media), to the way men touch women. Understand that all of these things are part of a whole that we need to change.

If you are a man, you may be thinking, "but I don't do those things!" I hear you. And: sexual violence is insidious. It's in the media we consume, the scripture we study, the air we breathe. It's shaped the way I think about my own body, and there's a lot that I'm working to unlearn. Inevitably these dynamics have shaped you too. But here's the good news: you can become aware of it and change it. And you can call out sexism, misogyny, sexual harassment, and rape culture in ways that I can't.

I wish this story weren't in our Torah. But Torah holds up a mirror to human life. What I really wish is that this weren't such a familiar story, then and now. We are all Avram: God calls all of us to go forth from our roots, from our comfort zone, into the future that God will show us. We need to go forth and build a world that is better than the one Avram knew.

That trajectory -- seeking to build a better world than the one we inherited -- is itself encoded in Torah, and in the prophets, and in the whole Jewish idea of striving toward a world redeemed. This week's Torah portion comes to us from a very early time in our human story. The familiarity we feel, upon reading this troubling text, reminds us how far we still have to go.

Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.

Posted with gratitude to my hevruta partner, who helped me think through this. Shabbat shalom to all.

Rabbi Roundtable at the Forward

The next installment in the Forward's Rabbi Roundtable has gone live. This week they chose to feature our answers to the question "Are Jews the inheritors of Eretz Yisrael?" Read all of our answers -- including mine -- here at the Forward.

October 21, 2017

The Open Invitation

Chodesh tov: a good and sweet new month to you!

Chodesh tov: a good and sweet new month to you!

Today we enter the month of Cheshvan, a month that is unique because it contains no Jewish holidays at all. (Except for Shabbat, of course.) After the spiritual marathon of Tisha b'Av and Elul and the Days of Awe and Sukkot and Hoshana Rabbah and Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah, now we get some downtime. Some quiet time. Time to rest: in Hebrew, לנוח / lanuach. We've done all of our spiritual work, and now we get to take a break. Right?

Well, not exactly.

When we finish the Days of Awe, we might imagine that the work is over. But I want to posit that the work of teshuvah, of turning ourselves in the right direction, isn't something we ever "complete"... and that Torah's been giving us hints about that, if we know where to look.

Last week we began the Torah again, with Bereshit, the first portion in the book of Genesis. The creation of the cosmos, "and God saw that it was good," the forming of an earthling from earth. Last week's Torah portion also contains the story of Cain and Hevel, the first sibling rivalry in our story. The two bring offerings to God. Hevel brings sheep, and Cain brings fruits of the soil, and God is pleased with the sheep but not with Cain's offering. Cain's face falls, and God says to him, "Why are you distressed?"

It's an odd moment. Surely an all-knowing God understands perfectly well why Cain is upset. This is not rocket science. Two brothers make gifts for their Parent, who admires one gift and pointedly ignores the other one?! Of course Cain feels unappreciated. This is basic human nature. How can it be that God doesn't understand?

The commentator known as the Radak says: God asked this rhetorical question not because God didn't understand Cain's emotions, but because God wanted to spur Cain to self-reflection. God, says the Radak, wanted to teach Cain how to do the work of teshuvah, repentance and return. Imagine if Cain had been able to receive that lesson. Imagine if Cain had had a trusted rabbi or spiritual director with whom he could have done his inner work, seeking to find the presence of God even in his disappointment. But that's not how the story goes. He misses the opportunity for teshuvah, and commits the first murder instead.

That was last week. This week, we read that God sees that humanity is wicked, and God decides to wipe out humanity and start over. But one person finds favor with God: Noach, whose name comes from that root לנוח, "to rest."

And God tells Noah: make yourself an ark out of gopher wood, and cover it over with pitch: "וְכָֽפַרְתָּ֥ אֹתָ֛הּ מִבַּ֥יִת וּמִח֖וּץ בַּכֹּֽפֶר / v'kafarta otah mibeit u-michutz bakofer." Interesting thing about the words "cover" and "pitch:" they share a root with כפרה / kapparah, atonement. (As in Yom Kippur.) It doesn't come through in translation, but the Hebrew reveals that this instruction to build a boat seems to be also implicitly saying something about atonement.

Rashi seizes on that. Why, he asks, did God choose to save Noah by asking him to build an ark? And he answers: because over the 120 years it would take to build the ark, people would stop and say, "What are you doing and why are you doing it?" And Noah would be in a position to tell them that God intended to wipe out humanity for our wickedness. Then the people would make teshuvah, and then the Flood wouldn't have to happen. God wanted humanity to make teshuvah, and once again, we missed the message.

The invitation to make teshuvah is always open. The invitation to discernment, to inner work, to recognizing our patterns and changing them, is always open. And to underscore that message, last week's Torah portion and this week's Torah portion both remind us: the path of teshuvah was open to Cain, and it was open for the people of Noah's day, and it's open now.

Even if we spent the High Holiday season making teshuvah with all our might, the work isn't complete. We made the teshuvah we were able to make: we pushed ourselves as far as we could to become the better selves we know we're always called to be. But that was so last week. What teshuvah do we need to make now, building on the work we did before?

The word kapparah (atonement) implies covering-over, as Noach covered-over the ark with the covering of pitch. What kapparah hasn't worked for you yet? Where are the places where you still feel as though your mis-steps are exposed? What are the tender places in your heart and soul that need to be lovingly sealed and made safe? This week's Torah portion comes to remind us that we still have a chance to do this work. Will we be wiser than the generation of Noah? Will we hear Torah's call to make teshuvah now with all that we are?

Here's the thing: as long as we live, our work isn't done. I don't know whether that sounds to you like a blessing or a curse. But I mean it as a blessing. Because it's never too late. Because we can always be growing. Because we can always choose to be better.

May this Shabbat Noach be a Shabbat of real menuchah, which is Noah's namesake, and peace, a foretaste of the world to come. And when we emerge into the new week tonight at havdalah, may we be strengthened in our readiness to always be doing the work of teshuvah, and through that work, may our hearts and souls find the kapparah that we most seek.

I'm honored and delighted this week to be at Kol HaNeshama in Sarasota, Florida, visiting my dear friend Rabbi Jennifer Singer who blogs at SRQ Jew. This is the d'var Torah I offered there for Shabbat Noach -- which I share with deep gratitude to Rabbi David Markus for sparking these insights.

October 17, 2017

Rabbi Roundtable at the Forward

The good folks at the the Forward have started up a new series they're calling Rabbi Roundtable. They chose 17 rabbis from across the denominational spectrum, and they're posing questions to us and sharing our answers.

The good folks at the the Forward have started up a new series they're calling Rabbi Roundtable. They chose 17 rabbis from across the denominational spectrum, and they're posing questions to us and sharing our answers.

The first one of these has just gone live, and the question they chose to ask this week is, "What is the biggest threat facing the Jewish people today?" Here are our answers: Rabbi Roundtable / What's the Biggest Threat to the Jewish People? Deep thanks to the editors at the Forward for including me as a leading voice of Jewish Renewal.

October 16, 2017

On stillness after the holidays

...This is our time to rest, like bulbs cradled in the embrace of the earth. It’s time to slow our breathing, like the shavasana pose that ends many yoga classes. We’ve been pouring out our hearts: now it’s time to wait and see what flows in to replenish us. Like the trees, like the bulbs, our souls need to lie fallow....

That's from my latest essay for The Wisdom Daily.

Read the whole thing: Why the stillness after the wave of Jewish holidays is so important.

October 15, 2017

Visions of Renewal in Connecticut

One of the great joys of being an unofficial ambassador for Jewish Renewal is getting invited to share spiritual technologies that have deeply shaped my life and my rabbinate with new communities that may not yet have experienced them.

One of the great joys of being an unofficial ambassador for Jewish Renewal is getting invited to share spiritual technologies that have deeply shaped my life and my rabbinate with new communities that may not yet have experienced them.

Over the weekend of November 3-5, Rabbi David Markus and I will be scholars-in-residence at Temple B'nai Chaim in Georgetown, Connecticut!

We'll be there over the weekend of parashat Vayera (the Torah portion is named after its first word, "And God appeared" or, more broadly "And God caused Abraham to see") so we've framed our introduction to Jewish Renewal through the lens of vision.

We'll be co-leading a musical, poetic, uplifting Kabbalat Shabbat service on Friday night; offering a Torah study on Shabbat morning; gathering with the community at 5pm for se'udat shlishit (the "third meal" of Shabbat, where we'll "dine" on poetry and song themed around yearning at that most poignant time of the week), havdalah, and some learning about angels in Jewish tradition. On Sunday morning we'll offer two short programs on "spirituality on the go" and on the mysticism of ordinary mitzvot.

Here's the full schedule for our weekend, and here's a Facebook event where you can indicate if you're coming. If you're in or near Connecticut and are able to join us, we'd love to see you there!

October 12, 2017

What we pray for

Today we shift from praying for dew to praying for rain, and as we made that shift, something occurred to me.

Today we shift from praying for dew to praying for rain, and as we made that shift, something occurred to me.

We say a special prayer for rain today on Shemini Atzeret, launching our season of asking God for rain in the daily amidah. (At Pesach, we say a special prayer for dew, launching our season of asking God instead for dew.)

No matter where in the world we live, between Pesach and Shemini Atzeret Jews don't pray for rain. Why? Because rain is an impossibility in the Middle East during the summer, and our tradition teaches us that we don't pray for the impossible. We don't ask God for what's just plain not possible. That would make a mockery of our prayer. Since rain can't fall in Jerusalem at that season, we don't ask for it. We ask for dew, instead: a form of abundance that's actually available at that time of year.

And yet I can't help noticing that we pray for peace all year long, on Shabbat and weekdays and festivals alike. On weekdays, when we're comfortable making requests of God, we pray for wisdom, and forgiveness, and abundance, and justice. No matter what day it is, we pray for healing for our broken hearts and our fallible bodies. Every night we pray for God's presence to accompany us and to spread a sukkah of peace over us while we sleep.

We don't pray for the impossible. Which must mean that all of those things -- peace and wisdom, forgiveness and abundance, justice and healing, God's presence with us and within us -- are possible, always.

On this day of holy pausing, may we be blessed with the felt sense that the things for which we most fervently pray are always already within our grasp.

Chag sameach.

October 11, 2017

Hoshana for Right Relationship

הושע הא / Hosha na, please save!

For the sake of Acting in good faith

For the sake of Boundaries and their maintenance

For the sake of Choosing to see clearly

For the sake of Directly naming what is broken

For the sake of Ending unconscious patterns

For the sake of Finding strength to speak

For the sake of Growth and transformation

For the sake of Holding firm to principle

For the sake of Integrity in all things

For the sake of Justice in every moment

For the sake of Keeping ourselves honest

For the sake of Love and awe in equal measure

For the sake of Making real teshuvah

For the sake of Noticing when we're culpable

For the sake of Opening ourselves to becoming

For the sake of Power wielded justly

For the sake of Questioning and discernment

For the sake of Repairing what we've damaged

For the sake of Standing in our truth

For the sake of Taking responsibility

For the sake of Understanding our own choices

For the sake of Victims of abuse, believed and honored

For the sake of Walking away from toxicity

For the sake of eXamining our behavior

For the sake of Yin and yang in balance

For the sake of Zeal to do what's right, not just what's easy:

הושע הא / Hosha na, please save!

Today -- the seventh day of Sukkot -- is also a minor festival in its own right, called Hoshana Rabbah. On this day it's customary to recite alphabetical acrostic prayers called hoshanot.

This is the hoshana that I most needed to pray this year. May its words ascend on high; may its implications sink deep into our hearts and shape our actions as we move into the new year.

For those who are interested, here is another contemporary Hoshana for Healing and Consolation by Rabbi Dr. Dalia Marx, published at the Open Siddur project in Hebrew and in English translation.

Chag sameach / a joyous festival to all.

October 8, 2017

Sukkah sky

If I could, I would invite you into my mirpesset sukkah when morning light paints the valley golden, or when twilight pinks the horizon, or when the moon is visible over the mountains to the east.

It's hard for photographs to capture the feeling of being in the sukkah: the rustling of the schach and decorations overhead, the scent of the cornstalks and the etrog, the way the structure sketches a room around you, at once indoors and outdoors.

But I can show you glimpses, photos taken from the place where I usually sit. I can show you slices of the light and the changing sky over the hills and houses. There are many bigger and fancier sukkot than ours, but none with a prettier view.

This year (so far) we've been blessed with warmth and fair weather over the first few days of the holiday. We've dipped in and out of the sukkah: eating there, reading there, hanging out with friends there, just relaxing there.

There's a poignancy to the sukkah: it's so beautiful, and so temporary. A reminder to enjoy every moment we can, before the sukkah comes down, before the decorations are packed away for another year, before the snows fall.

Related: Letter from the sukkah (2014), A sukkah of sticks and string (2016)

October 5, 2017

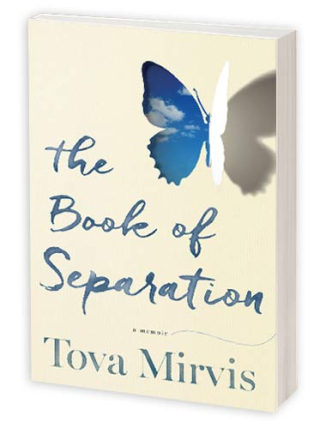

The Book of Separation, by Tova Mirvis

I don't entirely know how to write about Tova Mirvis' The Book of Separation. It is beautiful, of course. It is painful. It is rich. It is hopeful. It is the intertwined story of her divorce and her leaving Orthodoxy. And it's especially poignant for me to read as my own divorce continues; I can't help reading her journey through the lens of my own.

I don't entirely know how to write about Tova Mirvis' The Book of Separation. It is beautiful, of course. It is painful. It is rich. It is hopeful. It is the intertwined story of her divorce and her leaving Orthodoxy. And it's especially poignant for me to read as my own divorce continues; I can't help reading her journey through the lens of my own.

To leave a marriage, to leave a religion, you never go just once. You have to leave again and again.

Our divorce stories are not the same (moving out on my own was my first opportunity to keep a kosher kitchen; moving out on her own was her first opportunity to eat non-kosher pizza). But I am dazzled and sometimes griefstricken by how familiar her story feels to me. You never go just once. You have to leave again and again. Yes, that's my experience too.

Once the dishes are put in the oven -- my zucchini lined up in the pan like a fleet of green canoes -- I leave the kitchen to go check on the kids, who are playing happily. I study them as if searching for symptoms of a dreaded fever, worrying that the divorce fills their minds as persistently as it does mine, that they too cannot stop noting that this is the first Sukkot of the divorce, that during this year, everything is a first.

There were times when I had to put the book aside because reading it was too resonant with my own experience of ending a 23-year relationship and coming unmoored from every certainty I used to think I knew. There were other times when I eagerly picked it up again, unable to set it aside. Not only because it's well-written, although it is. Because it's authentic and real, and that's something I crave, especially now.

When the kids come to the table, we sing "Shalom Aleichem" -- the song that has started every Shabbat dinner I've ever attended, my whole family gathered round -- but with only our four voices, the prayer feels slight and vulnerable. // Here is the freedom and, alongside it, the price to be paid: loneliness.

Reading this book, I often found myself thinking of Leah Lax's beautiful and heartbreaking memoir Uncovered. Uncovered is about living a closeted life in the Hasidic world -- and eventually leaving Hasidism and, in her own words, finally coming home. Both of these are stories of painful growth and self-discovery and ultimately coming home into a self that the author tried for years to pretend that she didn't need to authentically be.

"Life," I continue on, wanting to impart this not just to Josh but to my younger self, "is about exploring and grappling and growing. You're allowed to change, even when it's painful. You're allowed to decide who you want to be."

On some level this is a story about claiming one's own truth, even when it flies in the face of what was "supposed" to be. It's a book about choosing to live honestly, instead of staying within the safety of pretending that everything is working when it's not. And that's enough of a universal theme that I suspect this book will resonate not only for those who have left a religious community, and not only for those who have ended a marriage, but for anyone doing the difficult spiritual work of growth and change.

Nothing can change, my mantra of so many years. Nothing can change. All this time, I saw it as a prison, a curse, but I hadn't realized that it was also a crutch, an excuse, a prayer. Change felt as alarming as anything I might have done -- so afraid of falling, so afraid of finding myself severed from all that was secure. All this time, I'd preferred to stay unhappy rather than to take a chance on what was unknown.

Change is scary and hard. Being severed from what was once familiar is scary and hard. I recognize myself in these words. Maybe some of you do, too. It's natural to be ambivalent about change: to resist it, to resent it, to crave it, to fear it. And yet I am increasingly certain that facing change is the work of midlife. (I think Father Richard Rohr might agree.) Reading Mirvis' words, I re-experience my own tumultuous journey from resisting change, to fearing change, to embracing change even when it comes with grief.

Now, without either ring, my finger looked naked. All that remained were the indentations the bands had carved into my skin.

I know that feeling. I still reflexively reach with my thumb to confirm that my rings are still there, even though I know they are not. I wore them for almost eighteen years. They shaped me, the marriage shaped me, indelibly. It's like when I wear tefillin. They leave a winding spiral on my arm, an inscription on my body that fades in the physical realm but sometimes lingers emotionally and spiritually. The promises I have made -- to the people in my life; to the tradition with which I wrestle and dance -- shape me. So do the promises I once made that I can no longer keep.

When we learned about [the Exodus] in school, the desert Jews were depicted as a foolish, ungrateful lot -- how could they bemoan such a painful past? Back then, I had yet to understand that leave-takings are slow and painful and carry their own losses, that you can miss even what you needed to leave.

I come away from this book awestruck by Mirvis' courage. I'm awed by the courage it took to leave an all-encompassing religious system that no longer fit, the courage it took to leave a marriage that no longer fit, the courage it took to write this dazzlingly authentic and honest memoir. I'm grateful that this book exists, and I recommend it highly. The Book of Separation gives me hope that even when change is difficult and painful, it can be redemptive, even holy. Kein yehi ratzon -- may it be so, for Mirvis, and for me, and for all of us.

Related:

A ritual for ending a marriage, 2016

Life in the imperfect tense, 2016

Repairing, Not Building Anew, 2017

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers