Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 79

January 20, 2018

"Come to Pharaoh," and whom we choose to serve

This week's Torah portion is called Bo, for its opening words ויאמר יהו׳׳ה על–משה בא על–פרעא / Vayomer YHVH el-Moshe, "Bo el-Paro" -- "And God said to Moshe, 'Come to Pharaoh.'"

This week's Torah portion is called Bo, for its opening words ויאמר יהו׳׳ה על–משה בא על–פרעא / Vayomer YHVH el-Moshe, "Bo el-Paro" -- "And God said to Moshe, 'Come to Pharaoh.'"

Most translations say "Go to Pharaoh." But the Hebrew is pretty clearly "Come." For me, the difference between "come" and "go" is that the first one connotes "the place where I am." If I say to my son, "Come here, I want to talk to you," I'm asking him to come where I am. If I say "Go over there," I'm telling him to go to the place where I am not. So when Torah says Bo el-Paro, I hear God saying, "Come here to Pharaoh -- to the place where I also Am." (This is not my own insight -- Zohar scholar Danny Matt sees this as an invitation to "come" into God's presence, too.)

We might prefer to imagine that God is not with Paro. Pharaoh is the exemplar of toxic power-over. He regards the children of Israel as subhuman. He describes them with words that connote vermin swarming. He's ordered policies that literally kill all of their male children. And yet with this one simple phrase, Torah reminds us that there is no place devoid of God's presence. Not even the place where Pharaoh is.

The next thing we read in Torah is a bit troubling: כי–אני הכבדתי את–לבו / ki-ani hich'bad'ti et-libo, "For I have hardened his heart." Whoa, hold up: God hardened his heart? Wouldn't it have been easier for God to simply soften Pharaoh's heart so that the children of Israel could be set free without all of this drama?

But if we look back at last week's Torah portion, we'll see a different phrase. Last week, Moshe and Aharon spoke to Pharaoh, and Paraoh hardened his heart and did not listen. Three times we read that Pharaoh hardened his heart and did not listen, before we reach this mention of God hardening his heart. (Many of our commentators observe this, among them Rashi.) I think Torah is teaching us some deep wisdom about the human heart.

The heart flows in the ways to which we habituate ourselves. If we practice gratitude every morning, even on the days when we're not "feeling it," we can train the heart to incline toward gratitude. If we practice compassion toward others, even on the days when we're not "feeling it," we can train the heart to incline toward compassion. And if we practice hardening our hearts -- maybe by telling ourselves that "those people" aren't our problem; they're a different generation, or their skin is different, or they dress differently or pray differently or speak a different language -- then we train our hearts to incline toward hardness. Like Pharaoh's.

Torah says God hardened Pharaoh's heart, but Pharaoh had already hardened it, time and again. I think God just got out of the way and let Pharaoh continue being who he had already shown himself to be. That doesn't mean God isn't with him. We don't get to say that God is only "on our side." But it does mean that Pharaoh's made his choices, and there will be consequences.

That's verse 1.

In verse 2, God continues that the purpose of the signs and wonders -- the ten plagues and our subsequent liberation -- is so that we may teach all the generations to come the story of the Exodus. This is our core story as Jews, and we tell it in our daily liturgy, in the Shabbat kiddush, and in the Passover seder.

And in verse 3, Moshe and Aharon say to Pharaoh, how long are you going to be like this? Let God's people go so that we may serve God. In God's words, שלח עמי ויעבדני / shlach ami v'ya'avduni, "Let My people go that they may serve Me." The root ע/ב/ד means service, both in the sense of the service the priests performed in the Temple of old (and the "services" we attend today) and in the sense of serving God with our hearts and our lives and our being. As we read earlier this morning, "Everyone serves something; give your life to Me."

Everyone serves something. The question is, do we serve Pharaoh -- emblem of commercialism and and overwork, dehumanization and xenophobia, all of which are still perfectly alive and well in our day -- or do we serve something else?

Judaism invites us to choose "something else." Judaism invites us to make the profoundly countercultural choice of spending 25 hours each week disengaged from work, not only physically but also intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually.

Judaism invites us to say: there is something more important than all of our making and doing and achieving, and that something is Shabbat rest. Not just "taking a nap," though the Shabbos schluff is a time-honored tradition, but opening our hearts and souls to the weekly rejuvenation that becomes possible when we disconnect from workday consciousness and open ourselves to something beyond ourselves.

Judaism invites us to set aside the worries of the workweek and take a deep breath that goes all the way to our kishkes, all the way to our insides. On the seventh day, Torah teaches, שבת וינפש / shavat va-yinafash -- God rested and was ensouled. (We sing these words in the prayer V'shamru each week.) When God rested from creating, God's-own-self became ensouled in a new way. So do we.

May this Shabbat be a time of real rest and re-ensoul-ment. May we be reminded of the things that are more important than our budgets' bottom lines. And may our lives be lives of service to God -- and to the spark of divinity manifest in every human being with whom we share this earth.

This is the d'var Torah I offered at CBI this morning (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

January 14, 2018

If we will it... (on #HolyWomenHolyLand, #MLK, and hope)

Recently I've been following a series of stories online, hashtagged #HolyWomenHolyLand -- written by a group of six rabbis and five pastors (all women) who have been traveling together in Israel and the Palestinian territories.

Recently I've been following a series of stories online, hashtagged #HolyWomenHolyLand -- written by a group of six rabbis and five pastors (all women) who have been traveling together in Israel and the Palestinian territories.

Their updates have been heartbreaking and awe-inspiring. They've met with parents from the Bereaved Parents Circle, with Women Wage Peace -- Jewish, Christian, Muslim, religious, secular, settler, Arab, Israeli. They've met with leaders and activists and ordinary people on all "sides" of the conflict. They've visited holy sites together. They've eaten and prayed and wept and learned together.

And one of the messages that keeps coming through, in their tweets and their Facebook status updates and their essays, is that women in Israel and Palestine insist that they do not have the luxury of losing hope. In the words of Maharat Rori Picker Neiss:

Consistently seeing in activists (Israeli and Palestinian) a confidence in the future, and a confidence that there is a future. To combat fear, one needs the confidence to hope. #HolyWomenHolyLand

— Rori Picker Neiss (@roripn) January 10, 2018

It's easy to look at the state of the world and despair. It is far more radical to cultivate hope -- and to take action toward the world of our hopes instead of the world of our fears. But that's the call I hear emerging from the rabbis and pastors who went on the #HolyWomenHolyLand trip...

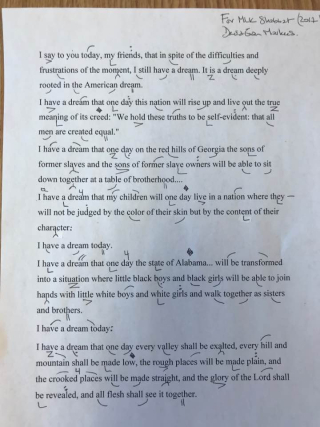

...and it's the call still emanating from the words we just heard from the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King z"l, who dared to dream that some day the sons of slaves and the sons of slave owners would sit down at a table of brotherhood.

Our own core story, unfolding in Torah even now, teaches that we were slaves to a Pharaoh in Egypt and our enslavement left us with kotzer ruach, shortness of spirit, such that we couldn't even hope for better. We got hammered down, like bent nails. (Here's a beautiful sketchnote illustration of that by Steve Silbert, based in a d'var Torah by Rabbi Sarah Bassin.)

Dr. King was talking about the literal descendants of slaves and slave-owners, not about the mythic, psycho-spiritual sense in which each year we recapitulate the journey from constriction to freedom. I don't want to elide or ignore that difference.

But I think there's a way in which in America today many of us have that kotzer ruach, that constriction of spirit, that Torah says our ancestors knew. There's injustice everywhere we turn. How do we cultivate hope when our own spirits may feel worn down by sexism and racism and bullying and gaslighting and bracing ourselves to hear the next horror story in the daily news?

Last week's Torah portion told us that our ancestors cried out in their bondage, and their cry rose up to God, and God answered. The first step toward change was crying out. When we cry out, even from a place of hopelessness, we open ourselves up. Maybe just a little bit, but in that little opening, the seeds of hope can be planted. We can tend those seeds in each other.

Theodore Herzl famously taught, "If you will it, it is no dream." The quote continues, "If you do not will it, a dream it is, and a dream it will stay." The first step is to dream of a future that is better than what we know now. The second step is to will that future into being -- to build and bridge and act to bring that future into being -- so that what now is only dream will become real.

We can't afford to lose hope, any more than our sisters and brothers in the Middle East can afford to lose hope. Dr. King's vision calls out to us: it is as necessary today as it was the day he first penned the words. May we be inspired to live in his legacy and to build an America, and a world, where everyone can be free at last.

This is the d'varling I offered this morning at CBI (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

I offered these words after chanting excerpts from MLK's "I Have a Dream," set to haftarah trope by Rabbi David Markus, which you can glimpse as the image illustrating this post. Deep thanks to R' David for sharing that setting; you can hear a recording of the whole thing and see the annotated haftarah on his website.

January 5, 2018

Rabbi Roundtable: Looking 50 years into the future

This week's Rabbi Roundtable asks us to imagine the Jewish community of 50 years in the future.

This week's Rabbi Roundtable asks us to imagine the Jewish community of 50 years in the future.

I'm surprised, this week, by how many of my colleagues don't seem to feel as optimistic as I do about the Jewish future!

You can read our answers here: We asked 20 rabbis, where do you see the Jewish community in 50 years?

January 4, 2018

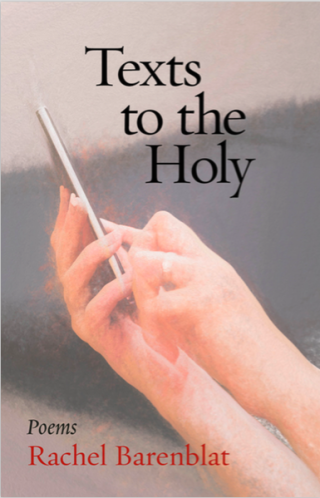

Texts to the Holy: now available for pre-order!

This is a happy week for publishing news around these parts!

This is a happy week for publishing news around these parts!

A few days ago I shared with y'all about Beside Still Waters, a volume for mourners to be released this spring by Ben Yehuda Press and Bayit: Your Jewish Home (now available for pre-order). Today I'm writing with more delightful Ben Yehuda news!

My next collection of poems -- Texts to the Holy, a collection of love poems to the (divine) Beloved, or to a lower-case-b human beloved, as you prefer -- is coming out soon from Ben Yehuda Press, and is now available for pre-order at an advance price of $9.95.

I'm starting to schedule readings for this spring. The book will officially premiere at a reading at the Tarrytown JCC (in Tarrytown, NY) at 1:30pm on March 18, where I will appear alongside two other Ben Yehuda poets, Maxine Silverman (author of Shiva Moon) and Jay Michaelson (the pseudonymous author of Is).

Stay tuned for information on other readings (and if you'd like to explore bringing me to your community for some combination of scholar-in-residence event and poetry reading, let me know!)

Meanwhile, here's some advance praise for the collection:

From Merle Feld, author of A Spiritual Life and Finding Words:

These poems are remarkable, radiating a love of God that is full bodied, innocent, raw, pulsating, hot, drunk. I can hardly fathom their faith but am grateful for the vistas they open. I will sit with them, and invite you to do the same.

From Netanel Miles-Yépez, translator of My Love Stands Behind a Wall: A Translation of the Song of Songs and Other Poems, and co-author (with Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi) of A Heart Afire: Stories and Teachings of the Early Hasidic Masters.

Rachel Barenblat’s Texts to the Holy bridges the human and Holy, so that we realize the bridge is really just an illusion to get us to realize that the human is itself Holy—“Bless the One Who separates / and bridges. Even at a distance / we aren’t really apart.” And yet, in every honest line, she also comforts us in the uncomfortable knowledge that realization does not exactly bridge the unavoidable separation from That to which we are so close, and that sometimes, “yearning is as close as you get to whole.” The Ba’al Shem Tov or the Aish Kodesh couldn’t have said it better.

(You can see other kind things people have said about the book on my website.)

This collection has a special place in my heart, and I think it's the best work I've put into the world. I hope you'll agree. Pick up a copy now!

January 2, 2018

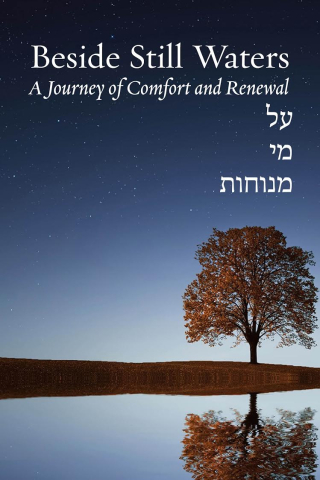

Coming in 2018: Beside Still Waters from Bayit and Ben Yehuda Press

One of the things I'm most excited about in the secular new year is a new publishing partnership between Ben Yehuda Press -- the press that published Open My Lips, and will publish Texts to the Holy this spring! -- and Bayit: Your Jewish Home, the new nonprofit organization I recently co-founded with six colleagues and friends.

One of the things I'm most excited about in the secular new year is a new publishing partnership between Ben Yehuda Press -- the press that published Open My Lips, and will publish Texts to the Holy this spring! -- and Bayit: Your Jewish Home, the new nonprofit organization I recently co-founded with six colleagues and friends.

The first book published jointly by Bayit: Your Jewish Home and Ben Yehuda Press will be Beside Still Waters: A Journey of Comfort and Renewal, a volume to support the journey through grief and remembrance, and you can pre-order a copy now.

One of the things I'm already loving about working with Bayit is that the Senior Builders span the denominational spectrum. I serve a Reform-and-Renewal shul; one of my fellow Senior Builders comes from the Conservative movement; another serves in a Reconstructionist context; still another comes from Orthodoxy. We have roots in, and connections to, all of Judaism's major denominations -- as well as to the trans-denominational world of Jewish Renewal. I'm hopeful that those roots and connections will help us collectively meet needs that aren't otherwise being met in the Jewish world. We're beginning our work with three keystone projects -- Publications, “Doorways” (a curated lifecycle resource), and a "Builders' Blog" (exploring how real innovation "works" in the Jewish world) -- and there are others in the pipeline about which I'm equally excited.

This Publications project arises out of several things that are important to me: serving as a conduit for the flow of Jewish Renewal texts and materials into the world, and the editorial work that was my passion before I entered rabbinical school. I couldn't be more thrilled about this first book that we're bringing to print, and about the fact that it's coming out in partnership with Ben Yehuda Press. Here's a description of the book:

Beside Still Waters: A Journey of Comfort and Renewal invites a timeless journey both classical and contemporary, spanning illness, death, grief and remembrance. This volume offers individuals and communities an easy-to-use, emotionally real and textually elegant companion for aninut (between death and burial), shiva (mourning’s first week), shloshim ( first month), yahrzeit (death-anniversary) and yizkor (times of remembrance). It includes resonant new translations, evocative readings, complete transliterations, and resources for circumstances often overlooked in other Jewish texts (miscarriage, stillbirth, suicide, when there is no grave, abusive relationships, etc.).

Developed in Jewish renewal’s trans-denominational spirit, Beside Still Waters is crafted for use in synagogues inside and outside the denominational spectrum, in hospitals, chaplaincy and pastoral contexts, funeral homes and home observances.

The volume features contributions from some of my favorite writers, artists, spiritual directors, and liturgists, among them Trisha Arlin, Alla Renee Bozarth, Shir Yaakov Feit, Rabbi Jill Hammer, Rodger Kamenetz, Irwin Keller, Rabbi David Markus, and the teacher of my teachers Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi z”l. (Some of my own work also appears in the volume as well.) The full contributor list is online here (and also at the bottom of our book announcement on FB.)

You can pre-order a copy at the Ben Yehuda website, and you can read more about the book via the announcement we just posted on Facebook.

Thanks in advance for sharing my joy!

December 29, 2017

The Last Jedi through a Jewish lens

Star Wars: The Last Jedi was deeply satisfying to me on several levels. I appreciated its feminism, especially in this current political moment when women's leadership has felt devalued in the public sphere. I enjoyed its subversive qualities. And most of all I appreciated what I understand to be the film's implicit theology, which resonates neatly with my own.

Star Wars: The Last Jedi was deeply satisfying to me on several levels. I appreciated its feminism, especially in this current political moment when women's leadership has felt devalued in the public sphere. I enjoyed its subversive qualities. And most of all I appreciated what I understand to be the film's implicit theology, which resonates neatly with my own.

(Please note: this post is full of spoilers! If you haven't seen the movie and wish to remain unspoiled, stop reading now!)

Luke tells Rey that the Force isn't a tool for lifting rocks or winning wars: it flows through everything, and is available to everyone. The movie wants to make sure we get that, so it offers that teaching in two forms: the pshat (surface) form of Luke flat-out saying so, and the remez (hidden / built-in) form of the discovery that Rey's parents were "nobodies." Rey isn't the next scion of some magical dynasty. She's just a regular person who's attuned to spirit and flow, and by extension, that means that any one of us could be (like) Rey.

This teaching about the Force is pretty close to my understanding of God. Many religious teachers (among them Reb Zalman z"l, the teacher of my teachers) have offered the caution not to confuse the finger pointing at the moon with the moon itself -- not to confuse the pointer for the point, as it were. The Force is "the moon itself." What Luke calls the Force is what I call God, who in the words of the Jewish mystics "fills all worlds and surrounds all worlds." The Jedi tradition in which Luke placed his faith -- and in which Luke lost his faith -- was always only a pointer, never the point.

And Rabbi Luke knew that, at least on some level, because he taught it to Rey: the Force doesn't belong to anyone. On the contrary, it flows through everything and everyone. The core question of hashpa'ah (spiritual direction) as I've been taught to practice it is "where is God for you in whatever's unfolding?" God flows through all aspects of our lives: the things we consider sweet, and the things we experience as bitter. As the Zohar teaches, leit attar panui mineh: there is no place devoid of God. Or in Star Wars' language, there is nowhere that the Force is not -- if we open ourselves to that flow.

For me the tensest moment of the film was when Luke went to torch the ancient tree. I thought of my tradition's great destructions. I cringed to think of ancient texts burning (and was deeply relieved to learn that Rey had pinched them before leaving!) -- in part because there are too many stories of precious Jewish texts and teachings going up in flames, from Roman times to Kristallnacht.

But even when enemies have tried to destroy my tradition (Babylon, Rome, the Nazis, you name it) they've failed, and one of the reasons for their failure is that the tradition is more than our texts, as precious as those texts are to us. The tradition lives in the minds and hearts of those who cherish it. The texts contain endless wisdom for which I am grateful, but they too are the pointer, not the point. And as long as there's someone left to uphold our teachings and study them and learn from them, then our teachings remain alive. As for us, so for the Jedi.

Luke and Kylo Ren are positioned as opposites, and that's not unreasonable, but (for a while, at least) they align in their desire to forcibly end the old ways. Luke wanted to burn Jedi history in order to wipe history's slate clean of his order and the mistakes that it had (and he had) made. And Kylo claimed he wanted to discard the past -- though given that his ultimate goal was still dominance, I don't think he was destroying the past so much as planning to recreate it in his own image. But both of them missed the point: the way to move forward is to know where and who we've been, flaws and all, and then to build from there.

That too feels to me like a very Jewish idea. Judaism today isn't identical to Judaism of a hundred years ago, or 500 years ago, or 3000 years ago. But neither is it completely discontinuous from what has been. Judaism is perennially renewing itself. I'm hoping that in Rey's hands, and in the hands of those she may someday teach, the Jedi tradition will do the same.

Given the timing of its release, I couldn't help watching the movie through the lens of the Chanukah story. Not the story of the violent rebellion against brutal Greco-Syrian hegemony, but the meta-story of how my tradition chose to valorize the tale of the miracle of the oil that lasted beyond all reason over the tale of that military victory. Because focusing on military might can all too easily lead to more death (like the Bar Kokhba revolt -- or like Poe's ill-advised choice to bring down the star destroyer)... but cultivating hope in dark times can give us the strength to carry on.

And the film ends on a note that resonates perfectly with that miracle-of-the-oil reading: a little kid recounting the story, and using the story to nurture a spark of hope. Hope for better than what exists now. Hope for a world without tyranny, a world of justice and kindness, a world where difference is celebrated and rights and freedoms are universally acknowledged to be the birthright of every living human being. May it come speedily and soon!

December 21, 2017

A woman of valor

A woman of valor! Worth more than

business class tickets to anywhere.

Every day I pack my son's lunch,

tuck his homework into his backpack.

I pay the mortgage. I ensure

my car is legal and fit to drive.

I fold and put away laundry.

I text beloveds who are far away.

I serve, I write, I create.

I teach and accompany and plan.

Every Friday night I light

twin fires of creation and Sinai,

chant sanctity into my wineglass.

When the co-op runs out of challah

I uplift a sandwich roll.

I make holiness from what I have.

Even on days when depression

whispers cruelty in my ear

I cup my hands around gratitude's spark

and I tell my child he matters.

And at the end of the week

I sing myself this song. I promise

I'm enough (but not too much)

and I am beautiful in God's eyes.

There's a tradition of reading Eshet Chayil ("A Woman of Valor") on Friday nights -- traditionally, a man reads or sings it to his wife. (There's a translation online here. I also love In loco eshes chayil by poet Danny Siegel.)

I was working recently on a poem that became a lament for the fact that there is no one to sing those words to me.

Then I thought, if there were a variant I could speak to myself, as a single woman and a working parent, what would it say? That's what sparked this poem.

December 16, 2017

Miketz: letting yourself dream

The beginning of this week's Torah portion, Miketz, describes two of Pharaoh's dreams. First he dreamed about seven healthy cows who got devoured by seven gaunt cows. Then he dreamed about seven healthy ears of grain that got devoured by seven thin gaunt ears. Disconcerting images.

The beginning of this week's Torah portion, Miketz, describes two of Pharaoh's dreams. First he dreamed about seven healthy cows who got devoured by seven gaunt cows. Then he dreamed about seven healthy ears of grain that got devoured by seven thin gaunt ears. Disconcerting images.

Both times, he woke and realized he'd been dreaming. And then one of his servants remembered the fellow named Joseph, languishing in prison, who was able to interpret dreams. And so Joseph was released from prison, and brought to Pharaoh to help him understand the meaning of his dreaming.

The teacher of my teachers, Reb Zalman z"l, wrote:

When my daughter, Shel, was 8 years old, she asked me, "Abba, when you’re asleep, you can wake up, right? When you are awake, can you wake up even more?"

(-- Expanded Awareness and Extended Consciousness)

The answer, of course, is yes. Yes, we can wake up more. We can wake from complacency. We can wake from routine. We can wake from taking things for granted. We can wake to hope and to wonder. That's the good news. The frustrating news is that such awakenings are rarely permanent. We wake from complacency and recognize that if we want a morerighteous world, we have to build it... and then we forget. We wake from routine and recognize that being alive is a miracle... and then we forget.

This is spiritual life: being awakened into awareness, and then falling out of awareness, and then awakening again. None of us can live in a perennial state of gadlut, expansive consciousness. The great thing about the fact that we keep falling asleep is that we can also keep waking up. We're designed to keep waking up. I posit to you that being "asleep" isn't actually a bad thing. Spiritually, maybe we need the oscillation between forgetting and remembering. And maybe being "asleep" helps us daydream.

Pharaoh was troubled by his dreams. We've all had that experience: a recurring dream that sticks with us long after the day's first cup of coffee. We wonder: what is the dream trying to tell us? What does it mean? My friend and teacher Rodger Kamenetz, author of The History of Last Night's Dream, teaches that dreams aren't "texts" to be "interpreted." Rather, they're landscapes of feeling. They can give us deep access to our emotions. (If this interests you, learn more about his practice of dreamwork.)

I wonder what would happen if we approached our waking dreams the way Rodger suggests approaching our sleeping dreams: entering the emotional landscape of the reverie, with a trusted guide and companion, and seeing what we can learn from that exploration of our yearnings. Waking reveries are different from nighttime dreams, but I think we should treat our daydreams with the same presumption of depth and meaning that we bring to thinking about the dreams that play out while we sleep.

I think our daydreams can tell us a lot about what we yearn for: not what we think we're "supposed" to want, but what our hearts and souls actually crave. Maybe we ache for love, or for comfort, or for justice, or for being fully uplifted in all that we are. But most of us are taught, in a variety of ways, not to credit those yearnings. What would happen if we chose to wake up: not from those dreams, but with those dreams? What would happen if we brought our daydreams more fully into our waking lives?

We always reach parashat Miketz at this time of year. I imagine there's something different, psycho-spiritually, about reading Miketz in Australia or Argentina where right now it's high summer. Where I live, this is a season of deepening winter. Long nights, short days, battening down the hatches... Winter's a great time to hunker down and pay attention to our dreams -- the sleeping ones, and the waking ones -- to see what they tell us about what we fear, and what we love, and what we yearn for.

What do you dream of: for yourself? For your family, whether blood or chosen? For your community? For your world?

If we allow ourselves to face our yearnings, we also have to face fear that our yearnings might not come to pass. The dreams of our hearts are tender. (If you're going to delve into them, I hope you do so with a trusted guide, maybe a therapist or spiritual director.) When Joseph helped Pharaoh understand his dreams, Pharaoh made decisions about the future of his nation (and ours, too). What changes might we make if we took our own dreams seriously -- the sleeping ones, and the waking ones too?

May this winter give you us space and safety we need to look at what we yearn for... and may we find the inner reserves of fuel we need in order to make those dreams come true.

With gratitude to my hevruta partner for opening up for me these connections between Miketz and dream.

Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.

December 13, 2017

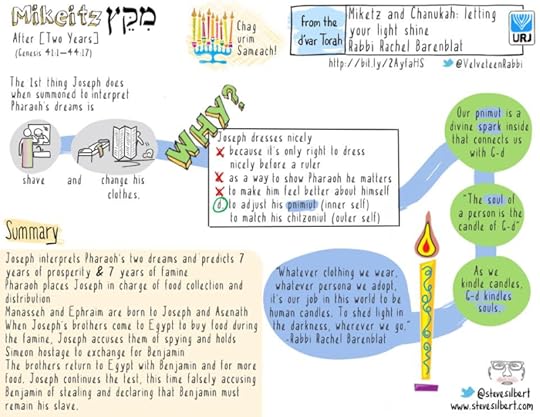

Mikeitz Sketchnote

My friend Steve Silbert has been drawing weekly sketchnote illustrations of each week's Torah portion. This week he writes:

This week’s Torah portion is called Mikeitz, which means “after”. In context, it’s two years after Joseph was sold into slavery. Since this parsha falls on the first night of Hanukkah I chose to sketchnote a dvar Torah by my friend Rabbi Rachel Barenblat. In her dvar Torah she connects this installment of the story of Joseph with Hanukkah through the divine spark that exists in us all. Near the end, she brings it all together by writing that "Whatever clothing we wear, whatever persona we adopt, it's our job in this world to be human candles. To shed light in the darkness, wherever we go."

Shalom.

And here's his illustration:

I'm honored to have inspired his sketchnote this week! I think this is such a beautiful way to engage with Torah.

You can leave him feedback on his Facebook page or on Twitter.

December 12, 2017

Rabbi Roundtable: "What are Jews, exactly?"

This week's edition of the Forward's Rabbi Roundtable asks, "What are Jews? — a race, a religion, a culture, an ethnicity, a nation….?"

This week's edition of the Forward's Rabbi Roundtable asks, "What are Jews? — a race, a religion, a culture, an ethnicity, a nation….?"

I'm glad to see that many of us rejected the possibility of Jews as a "race," for a variety of reasons. I'm intrigued by how many people came up with the metaphor of a family to describe who and what Jews are (and what connects us across our many diversities.)

Here are our answers: Rabbi Roundtable: What are Jews, Exactly?

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers