Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 77

March 3, 2018

Choose life: what Ki Tisa teaches us about Shabbat

The Israelite people shall keep Shabbat, observing Shabbat throughout the ages as a covenant for all time: it shall be a sign for all time between Me and the people of Israel. For in six days God made heaven and earth, and on the seventh day God ceased from work and was refreshed [or: was ensouled].

That's in this week's Torah portion, Ki Tisa. Many of us know these words because they have become a part of our Shabbat liturgy, as the prayer we call by its first word, V'shamru. We sing these words on Friday nights and on Saturday mornings before kiddush.

Immediately before these familiar verses, there is another instruction to keep Shabbat as a sign between us and God. But this one contains some more challenging language:

You shall keep Shabbat, for it is holy for you. He who profanes it shall be put to death: whoever does work on it, that person shall be cut off from among his kin. Six days may work be done, but on the seventh day there shall be a shabbat of complete rest, holy to God; whoever does work on Shabbat shall be put to death.

Oof.

The medieval commentator Rashi (d. 1105) clarifies that the death sentence only applies if the person does work on Shabbat in the presence of witnesses, AND if the person was warned, immediately before doing the work, what the penalty would be. This is a pretty common rabbinic move: taking something in Torah that startles us with its harshness, and adding qualifying stipulations that make it much harder for the harsh law to be applied.

The Sforno (d. 1550) is less apologetic about the starkness of this command. He writes that anyone who deliberately desecrates Shabbat thereby denies God Who created all things including rest. Someone who performs secular tasks on Shabbat has clearly lost consciousness of what Shabbat means, and therefore deserves execution. You make your choices, you live with the consequences.

I agree with the Sforno that our choices have consequences, but I read these verses a little bit differently. I see them not as prescriptive, but descriptive.

Another way to translate "מ֥וֹת יוּמָֽת," usually rendered as "will be put to death," is "he will surely die." This passage comes to teach us that one who doesn't honor Shabbat, who doesn't honor the holiness of resting from workday acts and workday consciousness, will bring themselves closer to death. One who works constantly, and lives in a state of workday consciousness 24/7, will be deadened thereby.

Every week when Friday night and Saturday roll around, we make choices. Will we disengage from work, and from our worries, and from 24/7 cable news, and from all the things that make us feel trapped like rats in a maze? Will we set aside our burdens and welcome the presence of that extra Shabbat soul enlivening us and enabling us to take a full, deep breath? Will we affirm that connecting with our deepest selves and with our Source matters more than our to-do lists and our deadlines?

That's the choice. We can let Shabbat transform us, or we can stick with the rat race. And if we choose the endless rat race, we're going to wind up feeling dead inside.

Choose rest. Choose Shabbes. Choose life.

This is the d'varling I offered this morning at my shul. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

March 2, 2018

Untie

Source of Mercy, untie my tangled places.

I'm a fine gold chain so knotted and snarled

I've forgotten how it feels to fall straight,

to let Your abundance cascade through.

Protector of Israel, when someone wounds

my beloveds I turn into an angry lioness.

Forgive me: I don't want to outgrow

this furious yearning to protect those I love.

Eternal Friend, help me relinquish my grudges,

especially those I hold against myself.

You know every hope and every ache.

All I want to want is You, and if I have You

I have all I need. Through time and space

Your glory shines, Majestic One.

This is a prayer-poem I began writing a couple of years ago to which I returned this morning. It began as a re-visioning and mashup of two pre-existing prayers: Ana B'Choach, which some recite on Friday nights, and the bedtime prayer of forgiveness which appears in the nightly shema liturgy.

My poem borrows some phrases from Reb Zalman z"l's translations of both of those prayers. It also grapples with the piece of the bedtime forgiveness prayer that challenges me most: the articulation of forgiveness not for those who have harmed me, but for those who have harmed those whom I love.

There are four names of God, or epithets for God, in this prayer-poem. Three of them are names that Reb Zalman z"l used often, and the fourth appears in traditional daily liturgy. The fact that there are four names of God was a conscious choice made in revision; I like how it evokes the four worlds.

Shabbat shalom to all!

March 1, 2018

On saying bedtime prayers with my son

My latest essay for The Wisdom Daily is a meditation on saying bedtime prayers with my son, and how that experience has changed. Here's a taste of what I wrote:

My latest essay for The Wisdom Daily is a meditation on saying bedtime prayers with my son, and how that experience has changed. Here's a taste of what I wrote:

...In recent days he’s shifted the language of his prayers. Not the shema or the angel song, but the “God bless…” section of the evening ritual. That litany used to begin with “Mommy and Daddy.” Then came both of his sets of grandparents, followed by “and all of my aunts and uncles, cousins and friends, and everybody else, amen.”

Most of the litany is the same as it ever was. But recently he chose to add his father’s new partner to the prayer list. Then he decided he wanted to add our cat and his father’s new cat. The new litany begins with “Mom,” on a line by itself, followed by “Daddy and [Girlfriend].” Then come the two cats, then come the grandparents, then everybody else...

Read the whole thing: After My Divorce, My Son's Bedtime Prayer Is A Nightly Reminder That I'm Alone.

February 28, 2018

In defense of dressing up on Purim

The Forward ran an article recently, by Elon Gilad, that argues that dressing up for Purim is a relatively new tradition, dating back to a particular banquet in Vienna in 1900. The article is interesting, but it has one of the worst headlines I've seen in recent memory: Wearing Costumes On Purim Is Not A Real Jewish Tradition.

The Forward ran an article recently, by Elon Gilad, that argues that dressing up for Purim is a relatively new tradition, dating back to a particular banquet in Vienna in 1900. The article is interesting, but it has one of the worst headlines I've seen in recent memory: Wearing Costumes On Purim Is Not A Real Jewish Tradition.

I beg your pardon?

When my eight year old woke this morning, he said to me, "Mom, it's almost Purim! I'm so excited! I've been waiting for this day for sooooooo long!"

He's excited about dressing up. Not about hearing the megillah, not about eating hamentaschen, and not about giving gifts to the poor, as fine as those traditions are. He's an eight year old kid, and what excites him about Purim is getting to put on a costume and be someone different for a night. He'll be dressing up as one of his heroes, a teacher from a favorite cartoon, and when he tried on his costume he practically levitated with joy.

(Fortunately he's too young to read the Forward.)

I object to the headline because it minimizes something people love about this holiday. I also think it ignores the extent to which masks and hiding are integral to the megillah of Esther. Esther's name shares a root with nistar, "hidden;" she hides her Jewishness until the time comes to reveal her true identity; even God is hidden in this book. (See last year's d'varling, What costumes can reveal.) Wearing costumes may be a newish tradition, but it can be rooted in the holiday's core text and its themes.

I also think Gilad is missing something when he traces the costume / mask tradition only to the year 1900. In the Code of Jewish Law, R’ Moses Isserles (1520-1572, also known as The Rama) writes, "There is a custom to wear masks on Purim, for men to wear women’s clothing, and for women to wear men’s clothing[.]" That's from the 1500s: still fairly recent, compared with some Jewish traditions, but clearly R' Isserles saw masks and cross-dressing as common enough to be mentioned as standard custom.

Beyond that, I object to the idea that anyone (even the Forward) gets to determine what is and isn't a "real" Jewish tradition. Yes, Jewish tradition often valorizes what's "old" and "traditional," but there's also always been a strand within Jewish tradition that glorifies making-new. Our liturgy teaches that God every day makes creation anew. When we take our traditions seriously enough to reinvent them and infuse them with new meaning, we too can be renewed. Halevai: we should be so lucky.

So what if dressing up for Purim doesn't come to us "mi-Sinai," as divine revelation directly from the mouth of God, as ancient as Torah itself? The practice of celebrating bat mitzvah for girls is a relatively new innovation too. So is ordaining women rabbis, or for that matter even counting us in a minyan. I thank God for those innovations, and I thank God for the practice of dressing up at Purim, too.

Play is an important part of spiritual life. There's a teaching that says that God spends 1/3 of God's time studying Torah, 1/3 being a matchmaker for human beings, and 1/3 playing with Leviathan, a giant mythic sea creature. Even God spends time in play -- and so should we. It's good for us to be silly sometimes. It's good for us to rejoice. And it's good for us to try on other clothes, other identities, masks and costumes that may allow us to show facets of ourselves that don't usually get expressed.

May our Purim be merry, and may our costumes teach us something about who we aren't -- and about who we are.

Noteworthy / related:

I'm a boy and these are my clothes, Rabbi Mike Moskowitz - why cross-dressing needn't pose a halakhic (Jewish-legal) problem for trans folks

Cross-dressing and transmisogyny on Purim, Rabbah Emily Aviva Kapor - why cross-dressing on Purim can be problematic and painful for trans folks (and a reminder to cis folks who may be cross-dressing on Purim to be conscious and careful)

February 26, 2018

Why I support the Child Victims Act

I'm going to Albany today to join colleagues (rabbinic and otherwise) in visibly supporting the Child Victims Act.

I'm going to Albany today to join colleagues (rabbinic and otherwise) in visibly supporting the Child Victims Act.

This legislation would change New York's statute of limitations for the crime of sexually assaulting a child, so that those who are sexually abused as children can seek justice. (You can read the bill here.)

A study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration of Children and Families found that 34% of childhood sexual abuse victims are under the age of nine. I have an eight year old, so that statistic hits home for me in a visceral way. At that age, most victims don't have the vocabulary to articulate what was done to them. Most victims aren't able to report their abuse until much later in life -- by which time, at least as New York law currently stands, nothing can be done. The Child Victims Act would change that.

If the #MeToo movement of the last few months has taught us anything, it’s that it is extremely painful and risky for victims of sexual harassment or assault — even those with power, money and connections — to speak out against their abusers. Now consider how much harder it must be for a child.

It should surprise no one that a vast majority of people who were sexually abused as children never report it. For those who do, it takes years, and often decades, to recognize what happened to them, realize it wasn’t their fault and tell someone. The trauma leads to higher rates of alcoholism and drug abuse, depression, suicide and other physical and psychological problems that cost millions or billions to treat — money that should be paid not by taxpayers, but by the offenders and the institutions that cover for them.

For these reasons, many states — including eight last year alone — have done the right thing and extended or eliminated statutes of limitations for the reporting of child sexual abuse. This has encouraged more victims to come forward and seek justice for abuse that was never properly addressed, if it was addressed at all.

New York, which has had no shortage of child sex-abuse scandals, should be on that list. In fact, it should be leading the nation on this issue. Instead it, along with Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama and Michigan, is one of the states with the least victim-friendly reporting laws in the country. New York requires most child sex-abuse victims to sue by the age of 23, 19 years before the average age at which such victims report their abuse...

(That's from a recent editorial from the New York Times editorial board: Albany, Pass the Child Victims Act.)

I did my chaplaincy residency at Albany Medical Center, and I have congregants who live over the border in New York state, so I feel multiple layers of connection to New York and New Yorkers. I also have beloveds who were sexually assaulted as children in the state of New York. For their sake, and for the sake of the (too many) others like them, I hope and pray that this legislation passes at long last.

I'm honored to stand with colleagues today (including my Bayit co-founder Rabbi Mike Moskowitz, who recently wrote Why on earth are Orthodox Jews opposing the Child Victims Act?) in support of the passage of the Child Victims Act.

New from Bayit for Purim: Esther + #NeverthelessShePersisted

Just in time for Purim, Bayit is releasing something new, created by founding builder R' David Markus.

Just in time for Purim, Bayit is releasing something new, created by founding builder R' David Markus.

Nevertheless, She Persisted: A Purim Tribute for Women's History Month

Here's what R' David wrote about it:

This trope mash-up of Esther and the 2/7/2017 Congressional Record (“nevertheless she persisted” silencing of U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren) commemorates Purim and Women’s History Month at a time when society especially needs brave truth tellers to hold back the tide of hate.

Purim affirms Esther’s stand against official silencing, abuse of power, misogyny and anti-Semitism. At first an outsider, Queen Esther used her insider power to reveal and thwart official hatred that threatened Jewish life and safety. We celebrate one woman’s courageous cunning to right grievous wrongs within corrupt systems.

The archetype of heroic woman standing against hatred continues to call out every society still wrestling with official misogyny, power abuses and silencing. For every official silencing and every threat to equality and freedom, may we all live the lesson of Esther and all who stand in her shoes: “Nevertheless, she persisted.”

If you click through to the post on the Bayit Builders' Blog, you'll find a soundcloud recording of the two texts in Esther trope, and also an annotated script in case you want to chant this in your own community. Find it here: Nevertheless, She Persisted: A Purim Tribute for Women's History Month.

February 24, 2018

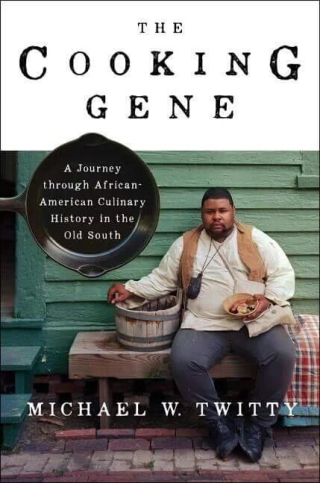

Michael Twitty's The Cooking Gene

I just finished Michael Twitty's book The Cooking Gene. It's a deep exploration of southern cooking, African cuisine, slavery and its continuing impacts, and how food shapes our sense of where we come from and who we are.

I just finished Michael Twitty's book The Cooking Gene. It's a deep exploration of southern cooking, African cuisine, slavery and its continuing impacts, and how food shapes our sense of where we come from and who we are.

I'm an outsider to the African American cultural history this book chronicles. But I know good memoir when I read it, and this is good memoir. It's also a rich, complicated exploration of race and history and memory. And from time to time it's also a meditation on Jewishness and food, and on those subjects at least I feel some reasonable semblance of expertise. Twitty chose Judaism as a young adult, taking on the mitzvot and the Jewish people's long history along with the histories of his genetic ancestors. (In addition to being a culinary historian, he's also a Judaic studies teacher. Wow do I wish I could bring him to my shul to teach my b'nei mitzvah kids.)

*

I read this book on my phone, on airplanes to and from my own birthplace in south Texas. If I'd read it on paper, I would have annotated the heck out of the volume: there would be underlined passages and exclamation points in the margins at the passages that moved or surprised me most.

As it is, I don't have quotations to share with you. I can only reference some of the passages that have stayed with me: the part where he writes about cooking on a plantation using his ancestors' tools and ingredients -- the part where he traces ingredients from Africa, transplanted along with the people for whom they were familiar -- the part where he writes about tracing his white ancestry (because white slaveholders raped the women they "owned," and therefore he is descended from slave owners as well as slaves) -- the part where he offers quotations from historical sources about the "Middle Passage" and what slavery actually entailed -- the part where he's teaching seventh graders about the Holocaust, and slavery comes up, and one of the kids tells him it was a long time ago and he should "get over it" -- the part where he writes about picking cotton and almost glimpsing the ghosts of his ancestors around him, noting that the ashcake they ate in the fields was truly the bread of affliction. (I will hear echoes of that this Pesach when I take my first bite of matzah.) The conversations with Low Country chefs and experts who are preserving Gullah food and culture, and with southern "good old boys" who are Confederate re-enactors -- and the agony of not being able to trace his whole family tree, because during slavery families were broken apart and records didn't preserve data because these human beings were considered chattel, not human beings...

What moves me most is Twitty's combination of love for where he comes from, and willingness to approach his history (which serves as a synecdoche for African-American history writ large) with generosity. He celebrates soul food without ignoring its roots in slavery and scarcity. He doesn't turn a blind eye to the horrors of slavery, nor the ugly ways in which those horrors still shape the relationship between whites and people of color in this country today. And, he makes the conscious choice to pursue connection, even with the descendants of those who enslaved his forebears, without spiritual bypassing or pretending away the damage done to African American communities to this day. Maybe that's why this book feels redemptive to me.

*

Reading The Cooking Gene, I found myself thinking a lot about the foods with which I grew up as a white (Ashkenazi) Jewish woman with immigrant grandparents in south Texas, and the foods I've embraced as an adult seeking a more multicultural approach to cooking and eating, and how race and history play into all of these.

I was particularly struck by Twitty's tracing of West African ingredients and flavors into American forms. I learned to love (and to cook!) Ghanaian food thanks to my ex-husband Ethan. He lived in Ghana for a year on a Fullbright grant right after college, and has returned there often since then. I only went to Ghana with him twice, but those trips impacted me. (See Dancing with the widow, an essay from 2000.) Our son has a Akan day-of-the-week name, and was blessed with Ghanaian moonshine and a libation poured to the ancestors at his naming ceremony where he also received his Hebrew name.

My two trips to Ghana don't make me an expert on anything, but they give me a personal connection with the place and the people I met while I was there. That feeling of connection intensifies the awfulness of reading Twitty's words about slavery. (On my first trip to Ghana I visited Cape Coast Castle, one place where slaves were loaded aboard ship to sail across the sea in unthinkable conditions toward even more unthinkable futures.) And that feeling of connection intensifies my delight at recognizing African ingredients transplanted into the southern American culinary vernacular, and recognizing the indigenous and African roots of some of the foods I grew up eating. (Here's a blog post from Twitty about the Colonial roots of southern barbecue -- a story that you can also read, in somewhat revised form, in the book.)

If you are interested in food, memory, race, or American history, this book is absolutely worth reading. (And if you are not yet interested in the culinary traditions of the African diaspora, I expect you will be by the time you finish.) I recommend it highly.

Posts by other folks:

How this African American Jew uses cooking to fuse his identities, Times of Israel

The author of The Cooking Gene on the black soul of American eating, Saveur

Michael Twitty: the Antebellum Chef, Garden & Gun

Kosher Soul Food Feeds Truth to History, Atlanta Jewish Times

February 23, 2018

Visiting where I come from with my son

When I walk around San Antonio, time telescopes. I'm here now with my eight-year-old son -- and I remember being eight in this city too, attending second grade at what was then called the Jewish Day School. As he spends time with his grandparents, I remember spending time here with mine.

When I walk around San Antonio, time telescopes. I'm here now with my eight-year-old son -- and I remember being eight in this city too, attending second grade at what was then called the Jewish Day School. As he spends time with his grandparents, I remember spending time here with mine.

We walk on the riverwalk and share illicit bits of bread with the ducks, and I remember feeding ducks at his age from the back of a motorboat on the Guadalupe. I'm sure my parents brought me to the riverwalk when I was his age, though I think the area where we walk now wasn't so built-up then.

He's come to San Antonio once or twice a year since he was born. There are places in my hometown that he remembers fondly but has outgrown. Like Kiddie Park. When we drive by it now on Broadway, my son remembers when the wee Ferris wheel looked huge and grand to him, and laughs.

This year 's highlight is visiting a ranch outside of Castroville, which belongs to two of my parents' friends. When we first mention the outing to him, he asks, "What's a ranch?" which makes my parents laugh: my little Yankee boy doesn't know what a ranch is! (My father explains.)

On the ranch we marvel at a chandelier made out of discarded deer antlers, learn about the difference between antlers and horns, and climb into a two-story treehouse that's built into a giant sprawling live oak. We pile into a red Suburban with the ranch manager and drive all around the land.

While we're out roaming the land we spot zebras, and springbok, and water buck, and two kinds of deer bounding past prickly pear, sweet acacia, and mesquite. We see sharp-horned Watusi cattle at their feeder. We get to feed honey nut cheerios to fluffy Sicilian miniature donkeys who follow us around and take cheerios from our palms.

It's sweet to be able to spend time with my son and my parents together, and to layer new memories for him (and me) atop the old. And when our time in San Antonio (and environs) is up, it's also good to return to our own beds and regular routines. The best of all possible worlds: to feel blessed in our going out, and in our coming home.

Shabbat shalom to all.

Photo: Texas flag, live oak tree, freight train. Taken in D'hanis, Texas.

February 17, 2018

God in exile, school shootings, and building the mishkan together

In this week's Torah portion, Terumah, we read וְעָ֥שׂוּ לִ֖י מִקְדָּ֑שׁ וְשָׁכַנְתִּ֖י בְּתוֹכָֽם / "Let them make Me a sanctuary, that I might dwell within them." (Or "among them.") The word "I might dwell" is שכנתי / shachanti -- the same as the root of the name Shechinah, our mystics' name for the Divine Presence that dwells with us, within us, among us.

In this week's Torah portion, Terumah, we read וְעָ֥שׂוּ לִ֖י מִקְדָּ֑שׁ וְשָׁכַנְתִּ֖י בְּתוֹכָֽם / "Let them make Me a sanctuary, that I might dwell within them." (Or "among them.") The word "I might dwell" is שכנתי / shachanti -- the same as the root of the name Shechinah, our mystics' name for the Divine Presence that dwells with us, within us, among us.

Jewish tradition teaches that God is both transcendent (far away and inconceivable) and immanent (indwelling and accessible). Our mystics call the transcendent, far-away part of God the Kadosh Baruch Hu (the Holy One of Blessing). The name they give to the immanent, indwelling aspect of God is Shechinah... and they imagine that She is in galut, in exile, with us here in creation.

To say that we are in exile is to say that we live in a state of distance from God. We live in a world of disunity and disconnect. We live in a world that contains trauma and tragedy. A world in which human beings harm other human beings.

That part is true of all human beings: we live in a state of distance from God, and that distance blinds us to the spark of divinity in each other, and that blindness enables terrible things.

We here in this room live also in a nation in which school shootings have become horrifyingly commonplace. A nation in which our government is paralyed and polarized and seemingly unable to act. What can it mean to say that Shechinah dwells with us or among us at a time like this?

The Talmud teaches that Shechinah weeps at our losses. I believe that God feels our grief, and our impotence, and our fury, and our trauma. She grieves at every life cut short. She grieves with every devastated parent.

At other times of trauma over the last year, some of you have asked me: why didn't God stop that from happening? How could a just God allow such injustice to persist?

The only answer I can offer is this: God gave the world over into our hands. Phrased another way: God doesn't intervene to change the natural world. Not to stop a hurricane, not to prevent an abuser from abusing, not to alter the course of a bullet. Because if S/He did intervene, then we would have to ask: why did God spare this child with cancer but not that one, why did God prevent this shooting but not that one?

The God I believe in didn't "allow" Nikolas Cruz to end seventeen lives. That's on us: on human beings, who have made guns -- including assault rifles -- easy to acquire and to misuse. (And as of a year ago, protections that had prevented those with serious mental illness from buying guns have been stripped away.)

And it's on us to make things better. To call Congress, to write letters, to sign petitions, to show up and lobby and protest and demand that our lawmakers create change that will keep our children safer. We don't have the luxury of falling into despair or feeling as though nothing will ever change. Because if we use our feelings of powerlessness as an excuse not to do anything, then nothing will ever change.

And our children need better from us than that. The memories of the seventeen killed in Parkland, Florida this week demand better of us than that. And God needs us to be better than that. Because our hands are God's hands in the world. The only way to soothe the Shechina's tears for Her children is to make the world a place of such justice and righteousness that God won't need to weep with us anymore.

In the first line of this week's Torah portion, God instructs Moshe: tell the people to bring gifts for the construction of the mishkan, the portable sanctuary where God's presence will dwell. The mishkan requires everyone's contributions.

And building a world redeemed requires everyone's contributions. Building a world in which school shootings are unimaginable requires everyone's contributions. Today is Shabbes, our "foretaste of the world to come," when we strive to live in the "as-if" -- as if the world were already redeemed. For today, we rest and rejuvenate as we are able. Tomorrow when the workweek begins again, we dive back into making this world better than it is today.

Because our schools need to be sanctuaries: safe places where our children can learn and grow without fear. And our synagogues need to be sanctuaries. And our homes need to be sanctuaries. And the whole earth needs to be a sanctuary: a place where God's presence dwells with us and within us, and no longer needs to weep.

Related: Prayer after the shooting by Rabbi Rachel Barenblat and Rabbi David Markus, October 2017

This is the d'varling that I offered at my shul this morning. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

February 16, 2018

Seven poems for ma'ariv

Many years ago, my friend Teju Cole put together a collection of contemporary poems with the intention of praying them daily as though they were liturgy. I remember printing them out and putting them on my desk in my study, and I remember praying them sometimes.

Many years ago, my friend Teju Cole put together a collection of contemporary poems with the intention of praying them daily as though they were liturgy. I remember printing them out and putting them on my desk in my study, and I remember praying them sometimes.

Alas, I no longer remember which poems he chose, though the fact that he had assembled a liturgy out of contemporary poetry was on my mind when I put together a morning service during National Poetry Month that interwove the Shabbat morning liturgy with the work of a variety of contemporary poets. (That liturgy featured Gerard Manley Hopkins, Norman Fischer, Mary Oliver, Wendell Berry, Adrienne Rich, William Stafford, Marge Piercy, Jane Kenyon -- some of the poets to whom I most often turn when I'm in need of spiritual sustenance.)

I had both of those sheaves of poems in mind -- Teju's, and my own -- when I assembled a collection of my own poems for use in daily prayer. I've written several poems that intentionally riff off of the words, images, and themes of daily Jewish liturgy. One day it occurred to me to see whether I could pull together a handout that follows the matbeah tefilah (structure of prayer -- e.g. the roadmap of themes and ideas that we touch upon in daily Jewish prayer) using my own poems for each of the stops along that daily journey.

What I came up with was this: Seven poems for ma'ariv. [pdf] Ma'ariv is the name we give to evening prayer in Jewish tradition, and these seven poems are intended to follow the themes of our evening prayers.

Why seven? Seven is a symbolic number in Judaism: the seven days of the week, seven colors of the rainbow, the seven "lower" sefirot that we inhabit as we count the Omer, seven wedding blessings (and seven times wedding partners circle one another), seven stops on the way to the grave... to name a few.

These seven poems are also intended to map to seven specific prayers: 1) the ma'ariv aravim prayer that blesses God Who brings on the evening; 2) the ahavat olam prayer that blesses God Who loves us and expresses that love through Torah; 3) the shema; 4) the ge'ulah blessing for redemption that evokes coming through the Sea; 5) the hashkivenu blessing for God Who spreads a shelter of peace over us as we sleep; 6) the amidah / prayer in which we stand before God and speak the words of our hearts; and 7) the aleinu prayer that closes our evening davenen.

I pray these poems sometimes as my abbreviated evening service. If you use them, I'm curious to know what works for you and what doesn't. (And if you've ever assembled a series of poems or readings intended to follow the flow of liturgical prayer in this way, I'd love to see it!)

A note on God-language:

Please note that that document contains the name יהו''ה, one of my tradition's holiest names for the One; if you print those pages, please treat them with the respect you would give a prayerbook.

I chose to include that Name, and not to translate or transliterate it, for a reason. That Name can be understood as a permutation of the verb "to be." Its untranslatability points us beyond all words. Our Creator is beyond language; our words can only approach the Infinite.

When I see the letters יהו׳׳ה, sometimes I render them aloud as Adonai ("My Lord"), sometimes as Shechinah (the immanent, indwelling Divine Feminine), sometimes as Havayah (the One Who Accompanies) -- and sometimes in still other ways. The unpronounceable / untranslatable Name reminds me that all of our names are only substitutes, and that our Source is beyond any words we can speak.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers