Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 75

April 20, 2018

Blue reflecting blue

It's traditional to tie a thread of blue into our tzitzit (the fringes on our prayer shawls).

Some say this is to remind us of when our ancestors "went up" to God and saw a sapphire floor that was "like" a floor beneath a throne that was "like" a throne. (I'm putting those words in quotes because -- as parashat Mishpatim makes clear -- an encounter with God is necessarily beyond all language.)

Others say that the blue thread in our tzitzit is "just" the blue of sky -- no need for mystical visions of sapphire, the blue threads simply remind us of the heavens. Still others see the blue thread as the blue of the sea. Maybe it's the blue of sea reflecting sky reflecting sea in endless conversation.

This morning I davened shacharit (morning prayers) from my little mirpesset (balcony) overlooking the water. I'm profoundly blessed to be spending this week in a place where I can see the sea, and the sky, in all of their ever-changing splendor.

One of the standard morning blessings praises God Who spreads the earth over the waters. Today I inverted it, blessing the One Who covers so much of this planet with the wonders of the sea.

Shabbat shalom to all who celebrate.

April 13, 2018

Shabbat shalom

May the Shabbat that is coming

May the Shabbat that is coming

bring comfort to all who grieve,

sweetness to all who are in need,

and balm for our wounded places.

May it bring us rest

and gentleness

and light.

May Shabbat enable us to shed

our world-weary weekday faces

and to soak in gratitude and wonder.

May we feel connected

with whose whom we love

and with our deepest selves

and with our Source.

May we emerge from Shabbat

nourished and ready

to meet the new week.

For now, may we prepare ourselves

to greet the Shabbat bride

with joy.

April 12, 2018

Yom HaShoah

Today is Yom HaShoah: Holocaust Remembrance Day. As a Jew and as a rabbi I feel that I "should" have something to say, but when I look inside to discern what my heart wants to articulate, I find only tears and silence.

Today is Yom HaShoah: Holocaust Remembrance Day. As a Jew and as a rabbi I feel that I "should" have something to say, but when I look inside to discern what my heart wants to articulate, I find only tears and silence.

In this week's Torah portion, Aaron's sons are killed and Aaron himself is silent. (I wrote about that a few days ago.) I often read his silence as a kind of stunned, grief-stricken numbness. The horror is too great: there are no words to adequately express it.

There's a resonance between that passage and how many of us relate to the Shoah. Millions of human beings rounded up like cattle, forced into hard labor, experimented-upon without anesthesia, murdered and cremated: it's unthinkable.

The attempt to wholly eradicate the Jewish people from the face of the earth: it's unthinkable. Mass extermination also of queer people, Roma, disabled and mentally ill people: it's unthinkable. Extermination camps and gas chambers: it's unthinkable.

The mind shuts down. The heart shuts down. The spirit shuts down. Because the alternative is screaming, wailing, rending our garments, a primal and existential outcry of why and how and where were You, God, when we were led to the slaughter?

Why? The only explanation is humanity's capacity for hatred -- which persists in our day. White supremacy, hatred of Jews, hatred of Muslims, hatred of queer / trans folks, hatred of immigrants: all are part of the same hateful dehumanization.

How? Because during a time of fear, hatred of the other became ascendant and was normalized. Which is why we have to be vigilant, and push back against fascism and xenophobia and white supremacy and hatred, wherever / whenever they appear.

Where were You, God? There are a lot of different answers to that question. My theology holds that God was with us in our suffering. God was with us in the camps and in the gas chambers. God wept with us then and God weeps with us now.

On this awful day of remembrance, may all who mourn be comforted. May the memory of the six million Jews murdered in the Shoah be for a blessing. May the memory of the eleven million (Jews and others) murdered in the Shoah be for a blessing.

And tomorrow, when this day of remembrance is behind us, may we all reconsecrate our hearts and hands to the work of building a world in which these hatreds, and the horrors to which they led, are a thing of the past, never to be repeated.

April 6, 2018

Pantoum for the Seventh Day

Step into the water.

You can't see the far shore.

Is the foam rising, or receding?

Take a deep breath and keep walking.

You can't see the far shore.

There's no knowing what's ahead.

Take a deep breath and keep walking,

Cultivating faith in your body.

There's no knowing what's ahead.

This is what the sages mean by

"Cultivating faith in your body."

Can you trust that you'll make it?

This is what the sages mean by

"The water is wide, I cannot get o'er."

Can you trust that you'll make it?

You're not crossing the sea alone.

"The water is wide, I cannot get o'er."

The only way out is through.

You're not crossing the sea alone.

Sing with me as we make our way.

The only way out is through.

Is the foam rising, or receding?

Sing with me as we make our way.

Step into the water.

Step into the water. Today is the seventh day of Pesach, regarded by tradition as the anniversary of the date when our ancient ancestors crossed the Sea of Reeds.

Is the foam rising, or receding? Midrash holds that the waters didn't part until a brave soul named Nachshon ben Aminadav stepped into the water and continued until the waters reached his mouth.

Cultivating faith in your body. See the teaching from the Netivot Shalom about how embodying faith enables us to sing.

The water is wide, I cannot get o'er. From a folk song, used in some communities as a melody for "Mi Chamocha," the song we sang at the sea.

April 4, 2018

A teaching from Torah on grief and on joy

In this week's Torah portion (at least according to the Reform lectionary), Aaron's sons Nadav and Avihu bring "strange fire" before God and are consumed by divine fire. In the haftarah assigned to this week's Torah portion, from II Samuel, a man named Uzziel places his hands on the Ark of the Covenant and God becomes incensed and strikes him down on the spot. Two deeply disturbing stories of people who apparently sought to serve God, "did it wrong," and were instantly killed.

In this week's Torah portion (at least according to the Reform lectionary), Aaron's sons Nadav and Avihu bring "strange fire" before God and are consumed by divine fire. In the haftarah assigned to this week's Torah portion, from II Samuel, a man named Uzziel places his hands on the Ark of the Covenant and God becomes incensed and strikes him down on the spot. Two deeply disturbing stories of people who apparently sought to serve God, "did it wrong," and were instantly killed.

The haftarah tells us that when Uzziel is killed, David becomes distressed and feels fear, and changes his plan for the Ark of the Covenant to come to Jerusalem. Instead he diverts it elsewhere. Only three months later does he bring the ark to the City of David with rejoicing, and music, and leaping and whirling before God. Meanwhile, in the Torah reading, Aaron's reaction to the death of his sons is existential silence. He says nothing. Maybe in the face of such a loss there's nothing one can say.

I don't have a good answer to the question of why God would behave this way. I read these passages instead as acknowledgments of a painful truth of human life: sometimes tragedy strikes and we can't understand why. These passages remind me that sometimes when we meet unexpected loss we have to withdraw, or change our plans, because the thing we thought we were going to do no longer feels plausible. And sometimes loss is a sucker punch, and words are inadequate to the reality at hand.

Yesterday was the seventh day of Pesach -- according to tradition, the anniversary of the day when our ancestors crossed the Sea into freedom. Midrash holds that when the sea split, everyone present had a direct and miraculous experience of God. The Mechilta of Rabbi Ishmael (Tractate Shira, Parasha 3) teaches that in that moment, everyone encountered God, "even the merest handmaiden." Another source (Tosefta Sotah) holds that even toddlers and babies witnessed Shechinah, the divine Presence.

Yesterday we re-experienced the crossing of the Sea, when we were redeemed into freedom and encountered God wholly. We sang and danced on the shores of the Sea, celebrating redemption and transformation, filled with hope. Today's Torah portion crashes us back into reality. How can we integrate the sweetness of Pesach, the miraculousness of the Song at the Sea, with this?

For me the answer lies exactly in the gear-grinding juxtaposition. Torah reflects human life and human realities. This is human life: wondrous and fearful, painful and glorious. It would be nice to have a waiting period between joy and grief, a chance to adjust to the psycho-spiritual and emotional shift between one and the other, but we don't necessarily get that luxury. Authentic spiritual life asks us to feel both of these wholly: our shattering, and our exultation.

Maybe those who constructed our calendar wanted to remind us that rejoicing and grief can fall of two sides of a single coin -- and that both can open us to encountering the Holy. The Kotzker rebbe points out that "there is nothing so whole as a broken heart." Sometimes we find wholeness not despite our brokenness, but in it. And when we feel broken, we can seek comfort in our tradition's ancient hope for redemption: whether we frame it in messianic language, or simply in the hope that life can be better than it is right now.

So here's my prayer for us today, arising out of these texts. When grief and loss intrude into our times of joy and celebration, may we have the wisdom of Aaron, to know when we need to fall silent because no words can convey the shattering of our hearts. And may we also have the wisdom of King David, to know when we need to shift our plans and give ourselves time to heal... so that when we are ready we can turn our mourning into dancing, and our silence into song. Kein yehi ratzon / may it be so.

This is the d'var Torah I offered at my shul this morning (cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

April 1, 2018

Seeking: seeing the ordinary through new eyes

On the eve of Pesach we search for hidden hametz by the light of a candle.

On the eve of Pesach we search for hidden hametz by the light of a candle.

On Thursday evening I hid ten pieces of bread. I called my son downstairs when they were all hidden, and I handed him a candle, a feather, and wooden spoon. With those traditional implements he searched the house for hametz. The following morning I took the pieces of bread, along with last fall's lulav, and burned them.

On the first two nights of Pesach we search for the hidden afikoman.

The seder has fifteen steps (like the fifteen physical steps up to the Temple in days of old), and one of them is Tzafun, "Hidden." At every seder a piece of matzah is declared to be the afikoman and then hidden. The kids hunt for it and then redeem it (in some households, holding the seder "hostage" for a prize, because until the afikoman is found and shared, the seder can't continue.)

Because of how the Jewish and Christian calendars overlap this year, our three days of (Jewish) searching bumps right into a (Christian) day when kids search for something hidden, too. Today my son will visit his Christian grandmother and search for colored plastic eggs filled with treats and small toys. He noticed the thematic resonance between our Jewish customs and this Christian one, and proclaimed it "awesome." I asked him what the searching means to him, and he said:

It's fun because it's about finding something new in regular places. If you find something new to do, then you always have it with you. And that makes it like you're traveling, finding new places, even though you're not going anywhere.

When I think about the candle-lit search for hametz, I think about the inner work of searching the corners of my heart for the last crumbs of old "stuff" I need to let go in order to be ready for freedom and transformation. When I think about the search for the afikoman, I think about the teaching that we hide the larger half of the broken middle matzah (rather than the smaller half) to affirm that there is more that is Hidden and Mysterious than we can ever grasp.

And now I will also think of the wisdom I received from my son. The candle-lit nighttime search, the afikoman hunt, and the Easter-egg hunt all take "ordinary" places and make them special and different because of the act of searching there. They enable us to "travel" without physically going anywhere, because they give us a traveler's wondering eyes. And when we train ourselves to seek the special within the ordinary, we acquire a skill that we can carry with us wherever we go.

As we move into the Omer journey of preparing ourselves to receive Torah anew, may we be blessed with eyes of wonder. May we continue to seek, and may what we find uplift us, challenge us, enrich us, and enable us ever-more to become the people we aspire to be.

Image: searching for hametz by candle-light.

March 30, 2018

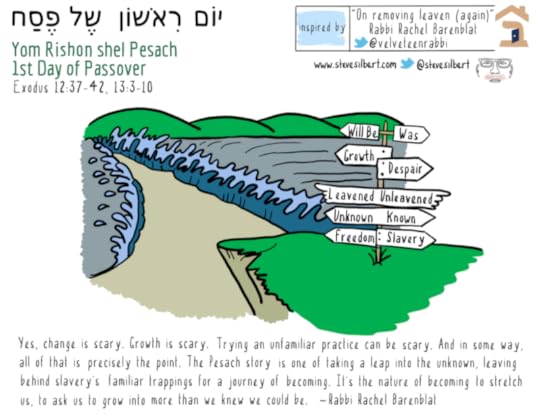

A sketchnote for the first day of Pesach

I'm deeply honored that Steve Silbert has once again found inspiration in one of my posts and created a sketchnote arising out of my recent post On removing leaven (again):

Find Steve's sketchnotes on his website. Thank you for doing me this honor, Steve -- this is a pre-Pesach gift for me!

Chag sameach (happy holiday) to all who celebrate.

March 29, 2018

On removing leaven (again)

I didn't grow up "keeping Pesach." By which I mean, my family of origin didn't remove the חמץ / hametz (leaven) from our house for seven (or eight) days. My family ate matzah at seders on the first two nights of the festival, and our seders were sweet and joyous and song-filled, but aside from two nights of matzah our dietary habits during Passover weren't any different from what they were the rest of the year.

I didn't grow up "keeping Pesach." By which I mean, my family of origin didn't remove the חמץ / hametz (leaven) from our house for seven (or eight) days. My family ate matzah at seders on the first two nights of the festival, and our seders were sweet and joyous and song-filled, but aside from two nights of matzah our dietary habits during Passover weren't any different from what they were the rest of the year.

By the time I got to rabbinical school, I wanted to take on more observance than I had grown up with. And, all marriages involve compromise -- and one of our areas of greatest difference was religious observance of all kinds. While married I maintained the practice during Pesach of not eating bread, or muffins, or bagels, or anything made of grain that had risen -- but I didn't remove hametz from my house, because my spouse was still eating it.

When my son was born I started doing the pre-Pesach ritual of bedikat hametz. Each year I've hidden bread crusts around the house for him to find, with wooden spoon and candle. Once he finds them, we burn them: a symbolic representation of the spiritual housecleaning that this season demands. But the hametz I was discarding was always only internal.

Two years ago on the day that would become Pesach I immersed in a mikvah to mark the end of my marriage. And last year as Pesach approached I was living on my own for the first time, which meant I could define my Pesach practice anew. It meant I could choose differently. For the first time, it meant I could choose to literally shed hametz.

I boxed up all of the hametz from my kitchen, and followed the custom of "selling" it to a non-Jewish friend for the duration. I bought a small set of bright red dishes for my son and me to use during the week, special Pesach plates and bowls to use only at this season. I hoped that eating on these pretty new plates would help to make the week feel special and set-apart, like a treat rather than a punishment. (And it did.)

Still, anxieties arose. Chief among them was what the week would be like for my son, who is a picky eater at the best of times. I want him to love Pesach. What if in my zeal to embrace a new level of religious observance, I alienated my kid from a festival I want him to savor? I went through several rounds of feeling the anxiety, and then thanking it for its service and sending it on its way. I experienced it as my yetzer ha-ra, trying to talk me out of a change in my religious practice because change is scary.

Yes, change is scary. Growth is scary. Trying an unfamiliar practice can be scary. And in some way, all of that is precisely the point. The Pesach story is one of taking a leap into the unknown, leaving behind slavery's familiar trappings for a journey of becoming. It's the nature of becoming to stretch us, to ask us to grow into more than we knew we could be. In a small way, my new experiment last year with a different kind of Pesach practice was a way for me to take a leap, as our mythic ancestors did.

Of course I didn't want to over-focus on ingredient lists and thereby pay insufficient attention to the festival's psycho-spiritual message of liberation. That would defeat the purpose of the practice, and leave me feeling enslaved to the holiday. But I don't think that was ever really a risk. I've been focusing on the holiday's teachings about liberation for years. My "growing edge" had to do with combining the psycho-spiritual with the practical -- via actually getting rid of my leaven.

Just because the pre-Pesach practice of removing leaven can be misused or damaging, that doesn't mean the practice has no value. I aspired to remove hametz in service of keeping me connected with God and with what I understand this festival to mean. The challenge lies in imbuing the holiday's external practices -- removing hametz, and making different dietary choices for a week -- with internal meaning. In that sense, it's the same challenge posed by every religious practice I know.

When I'm lighting Shabbat candles on Friday night, the difference between merely kindling a pair of wicks at the dining table and ushering in the holy presence of Shekhinah is an internal one. I have to make the effort to connect the two flames (as one of my favorite teachings holds) with the light of creation and the light of the bush that burned but was not consumed. Those meanings don't inhere naturally in the lighting. They're there because I invest heart and focus in putting them there.

I think the same has to be true for these Pesach traditions, too. Maybe we do them because our ancestors did them, or because others in our community do them, or because we want to see how they might change us. Regardless, it's our job to infuse the external acts with internal meaning. I can seek to make my house-cleaning and disposing of hametz a symbol of my willingness to let go not only of literal crumbs but also old habits, old narratives, old hurts that impede my ability to serve God.

Removing rolls, flour, and breadcrumbs from my kitchen didn't, by itself, make a difference in my life. But having removed them meant that every time I cast my eye over the pantry shelves I noticed their absence, remembered why they were gone, and tried to take the additional step of searching my inner places for old baggage that needs to be discarded so I can journey with God into becoming. Removing leaven gives me an opportunity to do some necessary work not only on my kitchen, but on me.

And like most of the inner work that we do, this isn't work that one only needs to do once. Each year the fires of my heart grow choked with ash and need to be cleaned. Each year I find sour stories and old hurts that need to be swept away. Each year the physical practice of disposing of hametz for a week offers me a reminder of the inner work to which my spiritual life perennially calls me... just as each year Pesach itself invites me into a recognition of how I feel constrained, and how I can go free.

March 28, 2018

New in The Wisdom Daily: Passover Calls Us To Leap

...Reb Nachman teaches that when the time has come to leap, we have to leap. No dilly-dallying, no tarrying, no anxiously writing scripts about what might go wrong. But how can we tell when the time has come? What if we don’t have the resources (inner or outer) to enable us to even imagine change? And what if we’re so habituated to the brokenness that we don’t even feel it anymore?...

That's from my latest for The Wisdom Daily. Read it here: Passover Calls Us To Leap Toward Freedom, Even If Just Internally.

New in the Forward: Squaring The Freedom Of Passover With The Struggles Of Life

We talk a lot about freedom at this time of year. Freedom from bondage. Freedom from our narrow places. Freedom from constriction. But what do we do with this talk of freedom if we ourselves feel stuck, if liberation seems impossible? What are the psycho-spiritual implications of that narrow place, the one that feels existential rather than circumstantial? What if we’re stuck with something: a diagnosis that isn’t curable, or financial ruin, or a sick loved one, or a grief that we know will persist?...

That's from my latest piece for the Forward.

Read the whole thing here: Squaring the Freedom of Passover With The Struggles of Life.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers