Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 71

August 20, 2018

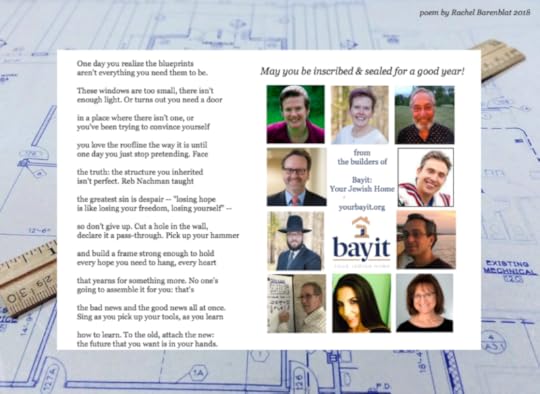

A holiday card from Bayit

A New Year's greeting from all of us at Bayit: Your Jewish Home:

May you build with joy, and may you be signed and sealed for a year of goodness.

August 18, 2018

Pursue

Run after justice

the way an eight-year-old

runs after the ice cream truck

chasing its elusive music

sandals slapping asphalt

until panting, calves burning

you catch it

and taste sweetness.

Run after justice

with the single-minded focus

a thirteen-year-old

brings to their phone.

Run after justice

the way the mother

of a colicky newborn

pursues sleep.

Run after justice

whole-hearted and open, as though

justice were your beloved

who makes your heart race,

whose integrity shines

like the light of the sun,

who makes you want to be

better than you are.

Run after justice. See Deuteronomy 16:20.

[W]hole-hearted. See Deuteronomy 18:13.

Shabbat shalom to all who celebrate.

I offered this poem at my shul this morning to close our Torah discussion. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

August 17, 2018

New year's poem 5779

As days are waning

The new year starts as days are waning.

I'm never ready when the first leaves turn.

Every Jewish day begins with evening:

darkness before light, since the beginning.

I'm never ready when the first leaves turn.

Roll the scroll toward the end of our story:

darkness before light since the beginning.

Am I ready to turn and face what's coming?

Roll the scroll toward the end of our story --

can I open my hands and let go of the summer?

Am I ready to turn and face what's coming?

You know what they say about endings.

I open my hands and let go of the summer,

paint every cracked and broken place with gold.

You know what they say about endings:

turn the page, start a chapter, begin again.

Paint every cracked and broken place with gold!

Every Jewish day begins with evening:

turn the page, start a chapter, begin again.

The new year starts as days are waning.

poem by Rabbi Rachel Barenblat, 2018

(You can see all of my new year's poems since 2003 online here -- most recent at the top.)

August 15, 2018

A renewed haftarah for the first day of Rosh Hashanah

Over the years I've posted a few different poems that riff on the haftarah (the reading from the Prophets) that tradition assigns to the first day of Rosh Hashanah, which is a text from 1 Samuel, the story of Chanah who poured out her heart in prayer.

I'm delighted to be able to share that I have a new resource to offer this year on that front. This is a revision of one of my Chanah haftarah poems, co-created with Rabbi David Markus, who has also set it to haftarah trope and recorded it.

You can find it in on the Builders' Blog at Bayit: Your Jewish Home in the Festival Year category, or by clicking through right here: Chanah in poetry and trope.

If you wind up using this in your Rosh Hashanah celebration, let us know how it works for you!

August 8, 2018

The awe of being seen: a sermon for Kol Nidre

It was four in the morning on Shavuot in the year 5770, also known as 2010. I was on retreat at Isabella Freedman, a Jewish retreat center in northern Connecticut. My son was seven months old.

It was four in the morning on Shavuot in the year 5770, also known as 2010. I was on retreat at Isabella Freedman, a Jewish retreat center in northern Connecticut. My son was seven months old.

My deepest regret, going on that retreat, was that I knew I wouldn't be able to hear Reb Zalman (z"l) teach. He was slated to teach at four in the morning, the last slot before dawn. And I had spent the last nine months not sleeping. There was no way I was staying up that late (or waking up that early), even to hear Reb Zalman.

But it turned out that my son didn't like the portacrib at the retreat center, and he woke up every hour all night long. By four, I had given up. I put him in the stroller. I rolled him over to the building where Reb Zalman was teaching. I draped a tallit over the stroller to make it dark in his little cave. And I rolled him in slow circles around the back of the room. While he slept, I listened to the teacher of my teachers as he taught until dawn.

Once, said Reb Zalman, there was a Sufi master who had twenty disciples. Each of his disciples wanted to succeed him as leader of their lineage. So one day he gave them each a live bird in a small cage. He told them to go someplace where no one could see them, and there to kill their bird, and then to return to him when their work was complete.

Some time later, nineteen of them came back with dead birds. The twentieth came back with a live bird still in its cage.

"Why didn't you kill your bird?" asked the Sufi master.

"I tried to do as you asked," said the student. "But no matter where I went, I couldn't find a place where no One could see me."

Of course, that was the student who deserved to lead the community: the one who knew that God is always present, and always sees us.

That, said Reb Zalman, is the meaning of יראה/ yirah, "awe" or "fear of God." Yirah means knowing that God is our רואה / roeh, the One Who sees us. It means knowing that we are always seen.

The letters that spell יראה/ yirah, "awe," also spell yireh, "vision" -- our theme for these Days of Awe at CBI this year. These letters in their various permutations are all over the Torah reading we dipped into last week on the second day of Rosh Hashanah.

On that day we read the Binding of Isaac. Maybe you remember the story: Avraham takes his son, his only son, whom he loves, up to a mountaintop. And there he almost sacrifices his son, until an angel calls to him to stay his hand. Ah, יְרֵ֤א אֱלֹהִים֙ אַ֔תָּה / yirei Elohim atah, says the angel: now I know that you have that feeling of awe; you know you are seen.

It's then that Avraham sees the ram. He doesn't see the thing he most needs until he first knows himself to be seen. And Avraham names that place "God-sees," because "On the mountain of God there is vision." Or maybe, on the mountain of God there is awe. Or maybe, when we allow ourselves to feel awe, and to feel seen, we can see things we couldn't have seen before.

Here are a few other words from our tradition, from the Unetaneh Tokef prayer that we daven on Rosh Hashanah and on Yom Kippur:

כְּבַקָּרַת רוֹעֶה עֶדְרוֹ, מַעֲבִיר צֹאנוֹ תַּֽחַת שִׁבְטוֹ, כֵּן תַּעֲבִיר וְתִסְפּוֹר וְתִמְנֶה, וְתִפְקוֹד נֶפֶשׁ כָּל חַי

Just as a shepherd sees the sheep and makes them pass under the staff, so do You account for the souls of all who live...

"Just as a shepherd sees the sheep..." God is our shepherd: we know that metaphor from the psalms. A shepherd, a רועה, is someone who looks after his charges. There's Hebrew wordplay here: רואה (spelled differently, but sounds the same) means one-who-sees, or vision-er. God is our shepherd, and God is the One Who sees us, Who visions us into what we have not yet become.

Our tradition teaches that God sees all of our best qualities, and all of our worst ones. Every beautiful and amazing and remarkable thing we have ever done, and everything shameful and humiliating and hateful, too. Tonight invites us to be laid bare before God. In our beauty and our love, and in our cowardice and our cruelty to others and to ourselves.

Our tradition teaches that for sins against God -- missteps where we harmed ourselves or our Source, where we failed to live up to who we know we could be -- Yom Kippur atones. Where we've harmed each other, we need to make teshuvah and do better -- but where we've harmed ourselves and our God this day itself can wipe the slate clean. Here's the thing: in order for us to feel forgiven by tomorrow night, we have to let ourselves be laid bare tonight. Not for the sake of wallowing in our own missteps. For the sake of the change in us that can come when we know we are seen.

Okay, time to get real: how many of us don't believe a word I just said?

God as a shepherd, making each of us pass beneath the staff and taking note of all of our actions and choices. God Who sees us. All of our deeds and choices written down in some mystical Book on high, the Book of Life and the Book of Death and by tomorrow night we'll be inscribed in one or the other for the year to come. Who here thinks all of this is really a load of malarkey?

The truth is, it doesn't matter whether you believe it or not.

I mean, it may matter profoundly to you. I hope that it does matter to you: what you believe, whether you believe, what you can believe in. But whether or not you believe in gravity, if you drop something it will land on the floor. And whether or not you believe in a God Who sees us, today is about being seen. Because God or no God, each of us can see ourselves clearly -- though we don't usually want to. And I get that. Seeing ourselves clearly can be uncomfortable, and most of us don't choose discomfort most of the time.

Yom Kippur invites us into the squirm-inducing feeling of being completely seen. Why is the intimacy of being seen so agonizing? Because we don't like everything that we are. Because we fear that if someone really sees us, they'll turn away. That's why people spend a lifetime trying to only show our good side: dressing to impress, pretending away our doubt, accentuating the positive.

But that's not being real. That's not being whole. And I don't want to only be loved if I put on a happy face, or if I'm careful to show only nice emotions, or if I hide my flaws and my mistakes and my insecurities. And it's just as damaging in the other direction: I don't want to only be loved if I hide away my strength and my splendor and my light, either.

In a real friendship, I don't have to hide either my brokenness or my strength. And if that's true with my friends, how much more true with the Beloved Friend our tradition names as God.

Authentic spiritual life invites us to be real. And because it's human nature to shy away from feeling our feelings, Jewish tradition gives us today. Yom Kippur says: it's time to get real. Right now. That's what we're here for. It's time to be completely seen, in all of our beauty and all of our shame. And it's time to know that we are loved: not despite who we are, but precisely because of who we are, flaws and all. Our daily liturgy makes us that promise every single night and morning: we are loved by unending love. Not "when we're perfect." Not "when we pretend." But always.

Maybe you don't believe in God. In the words of my teacher Reb Zalman z"l, I hope that sometime in the year to come you'll tell me about the God you don't believe in. Truly: I want to know! But okay, for now there's a God you don't believe in, and maybe that's the Shepherd, or the Friend, or the Judge taking stock of our choices on high.

So what would it feel like to look at yourself unflinchingly and to respond to all of your strengths and your failings with ahavat olam, that unending love that our liturgy describes? Whether or not you believe in a God Who sees you and loves you, take tonight to see yourself as clearly as your inner eyes will permit. Take stock of yourself, in all that you are. And cultivate love for yourself: not a facile surface love that requires you to pretend away your mis-steps, but a mature love, a whole love, a holy love that flows precisely from seeing yourself clearly. Not for the sake of self-flagellation or self-aggrandizement, but for the sake of the new vision of yourself you can call into being when you feel the awe of being seen.

God our ro'eh, our Shepherd and our Vision-er, invites us into a new vision of who and how we can be in the year to come. Or maybe we invite ourselves into that vision. And maybe those are two ways of saying the same thing. Either way, the vision beckons, once we open ourselves to awe: the vulnerable, trembling feeling of knowing that we are seen.

Our spiritual ancestor Avraham allowed himself to feel awe -- probably mixed with some anxiety, and even some despair. Remember, his only son was bound on an altar and he was holding a knife in his hand. The world must have looked bleak to him in that moment. His vision of his own self must have looked bleak to him in that moment: everything he had done, everything he had not-done, everything that led him to that terrible moment. But when he let himself feel the awe of being seen, his eyes were opened to something new right in front of him. The sheep caught in the thicket changed everything.

On Rosh Hashanah morning I spoke about the need to vision a world of justice and ethics and human dignity, and to take action toward building that world. Sometimes we take action toward building that world fueled by the fires of our own righteous indignation. And sometimes we take action toward building that world out of a place of desperation, a place of recognizing where we've fallen short. Both of those are necessary. Both of those are real.

It's Kol Nidre night. If we let ourselves feel the awe of being seen, what might we see -- in ourselves, in the year to come -- that we couldn't see before?

This year my shul's theme for the Days of Awe is Vision. My sermons reflect and refract that theme in different ways.

Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.

A vision of better: a sermon for Rosh Hashanah morning 5779

There's a meme going around the internet -- maybe you've seen it -- that says, "if you want to know what you would have done during the Civil Rights movement, you're doing it now."

I'm too young to remember Black people being harrassed and beaten for sitting at a lunch counter, or the Freedom Riders risking their lives by riding interstate buses into the segregated south.

But in the last few months we've seen migrant children ripped from their parents and imprisoned in cages, and some of their parents have been deported with no apparent plan for reuniting the families thus destroyed. There's a referendum on our ballot in Massachusetts this November that would strip rights from transgender people. There's mounting fear that Roe v. Wade will be overturned. We've seen attacks on the freedom of the press, widespread attempts at voter suppression, and actual Nazis running for Congress.

If I want to know what I would have done during the Civil Rights movement, I'm doing it now. So what am I doing now? Too often the answer is "nothing" -- I'm overwhelmed by the barrage of bad news. Many of you have told me you feel the same way, paralyzed by what feel like assaults on liberty, justice, and even hope. So much is broken: it's overwhelming.

So much is broken. It's overwhelming. There's no denying that.

But one of the dangers of overwhelm is that we become inured to what we see. It becomes the status quo. Police violence against people of color, business as usual. Islamophobia and antisemitism, business as usual. Discrimination against trans and queer people, refugee children torn from their parents, xenophobic rhetoric emanating from the highest levels of government: business as usual. It's so easy to shrug and say, that's the new normal. And it's easy to turn away, because who wants to look with clear eyes at a world so filled with injustice?

Many of you have heard me quote the poet Jason Shinder z"l, with whom I worked at Bennington when I was getting my MFA. He used to say, "Whatever gets in the way of the work, is the work." If the overwhelm of today's news cycle is getting in the way of the spiritual work we need to do, then it becomes the doorway into that spiritual work.

Because the real question is, what are we going to do about it? How does this season of the Jewish year invite us to work with this overwhelm?

It's Rosh Hashanah, the day our tradition names as Yom Ha-Din, the Day of Judgment. If I told you that our two big fall holidays map to love and to judgment, you might have guessed that the birthday of the world would be the day of love, while Yom Kippur would be the day of judgment. But it's the other way around. Our tradition connects Yom Kippur with chesed, unbounded love. Today is the day of gevurah, the day of din: boundaries, and strength, and judgment, and discerning where we've gone astray.

Many of us feel that the whole world has gone profoundly astray. And the first step toward fixing that truth is facing that truth. We must not turn away.

I want to pause here to say: of course we can turn away sometimes. Everyone needs to turn away sometimes. Many of you have come to me with increased anxiety and depression because of the horrendous injustices in the world around us, and I have often counseled taking Shabbat away from the news cycle. No one can carry the weight of the world all the time, and the heart and soul can't be healthy if they're constantly marinating in outrage and trauma. By all means, turn away when you need to. In fact, consider turning away before you need to, so that you can get the sustenance you need in order to turn back.

Turning back is the quintessential move of this time of year. The Days of Awe are all about teshuvah: repentance, return, turning ourselves around, re-orienting ourselves in the right direction again. Turning back is what we're here for today. Turning to face what's broken in the world, and then doing something about it.

The first step is opening our eyes and choosing to see. Choose to see hatred of immigrants and fear of difference. Choose to see assaults on voting rights. Choose to see white supremacy and racism. Choose to see injustice both large and small. It really is tempting to turn away. But before we can fix what's broken, we have to see it clearly.

Of course, we may not all agree on what needs repair. One thing that doesn't help us is the human tendency toward homophily -- the tendency of "birds of feather" to "flock together." (And anytime I think or speak about homophily, I owe a great deal to my ex-husband Ethan, who wrote on this subject in his book Rewire.) It's human nature to surround ourselves with people with whom we agree: Democrats hang out with Democrats, and Republicans with Republicans. (And so on.) I used to imagine that the answer was simply to expose ourselves to other viewpoints, but I've come to believe that that's insufficient. I mean, yes, encountering other viewpoints is broadening. But it won't fix this problem.

Because this isn't just a problem of information flow. It's a problem of fundamental human disconnection, of which the information flow is a symptom. It's a spiritual problem. And the spiritual question it asks of us is exactly the question of this moment in the Jewish year: am I doing the work I need to do? Where do I need to course-correct? Where do I need to be more generous in how I see myself and others, and where do I need to draw a firmer line?

We can disagree on which media source is the most trustworthy, but we shouldn't accept rhetoric that holds that the free press is the enemy of the republic. We can disagree on who to vote for, but we shouldn't accept systemic voter suppression. We can disagree about which rights we hold most dear, but we shouldn't accept the dismantling of human rights and dignity for anyone.

Siddhartha Mitter writes that the first question we should ask any political aspirant is, "How does human dignity shape your vision of society?" It's a question, he notes, that "can admit many answers—'liberal,' 'conservative,' 'progressive,' etc. It’s not a question of partisanship and tactics. It’s a question of morality." Policies that diminish human dignity are wrong. This is a fundamental Jewish value, and it's a value that we need to center as we move into the new year.

The new year demands that we envision a better world, and then find the persistence and commitment to figure out how to get from here to there. The new year demands that we figure out how to build bridges with those with whom we disagree, without endangering the most vulnerable among us. Migrant children need to be welcomed and cared-for, not caged. Refugees need to be protected, not deported. Trans and queer people need to be valued and uplifted, not harmed. People of color need to be valued and uplifted, not harmed. Jews and Muslims and Hindus and Sikhs need to be valued and uplifted, not harmed.

The new year demands that we stand firm against unethical policies without demonizing the people who enact those policies. Jewish tradition is clear that every human being is made in the image and the likeness of God, and every human being is animated by a soul that is fundamentally pure. That is true even of those with whom we most profoundly disagree. But Jewish tradition is also clear that we make choices, and those choices can obscure our pure souls with schmutz. And when our choices pull us askew from what God and our tradition's highest values ask of us, we need to make teshuvah, we need to repair and to return.

Vision is our theme for this high holiday season at CBI. That theme calls us to ask: what do we need to see? What are we reluctant to see? What would it be like to see differently? Because if we can en-vision a better world, then we can build that better world. As the Psalmist wrote (and as we've been singing for a month now) לוּלֵא הֶאֱמַנְתִּי לִרְאוֹת בְּטוּב-יְהוָ”ה בְּאֶרֶץ חַיִּים / Lulei he'emanti lirot b'tuv Adonai b'eretz chayyim. "What if I wholly believed to see the goodness of God in this land of life?" What if I could really and truly believe that I would see God's goodness in the world? What would that faith feel like?

The way to cultivate that faith is to act. You want to see God's goodness in the world? Then do something to bring that goodness into being. "We are loved by an unending love," says Rabbi Rami Shapiro's poetic riff on Ahavat Olam. "We are embraced by arms that find us even when we're hidden from ourselves. We are touched by fingers that soothe us even when we're too proud for soothing. We are counseled by voices that guide us..." [Listen to it here.] And he also writes, "ours are the arms, the fingers, the voices."

It's up to us to see a better world, and then to make that vision real. In this sense, we're all called to be prophets, and then to build our vision into being. A prophet, in Jewish tradition, is someone who exhorts us to do and be better. We need to envision a better world than this, and then we need to set our hands to the task of building that better world.

That's how we make teshuvah. Teshuvah is an evergreen high holiday theme, but this year I feel a new urgency. This year we need course correction, and we need vision.

It takes vision to imagine a world where the vulnerable are protected, and the strong lift up the weak. It takes vision to imagine a world where the planet's abundance is truly shared. It takes vision to imagine a world where no one feels diminished by anyone else's mode of dress or skin color or gender identity or way of worshipping. It takes vision to imagine a world where no one would seek to diminish anyone else's rights or dignity.

It takes vision to imagine a world where no one exercises entitlement to or dominion over another human being. A world without rape and sexual assault. A world without white supremacy. A world without antisemitism or Islamophobia. The world Judy Chicago wrote of in her poem that we often sing as part of our Aleinu: "and then all will be so varied, rich, and free / and everywhere will be called Eden once again."

We must imagine that world -- and then we must build it. I know that may feel implausible. I know that so many hopes feel precarious right now. I want to honor that, even as I challenge us to draw strength from how far our nation has come. Once upon a time chattel slavery was the law of the land. It was legal to own another human being. That changed because of hard work, and activism, and legislation, and struggle.

And that's what these times demand of us, too. So that our transgender loved ones can be safe and protected. So that women continue to have ownership of our own bodies. So that the rights of marriage and adoption granted to people of all sexual orientations are not taken away. So that the laws that protect our nation's fragile environment are not gutted. So that white supremacists will understand that (in George Washington's words) to bigotry we will give no sanction -- that hatred of any person is tantamount to hatred of all people, because we are all created in the image and the likeness of the Divine.

Teshuvah calls us to turn toward God, turn toward our highest selves, turn toward our ideals. But it's not enough to just aim ourselves in the right direction: we also have to do something about it.

So what are we going to do? Will we register new voters and fight voter suppression? Will we work toward affordable health care, or to protect the environment? Will we take a stand against prejudice and unethical behavior? Will we find a candidate who inspires us, and support them with our phone calls or our wallet? Will we urge our public servants to put human dignity front and center in every choice they make about how to govern?

Teshuvah calls us to resist apathy, and overwhelm, and the internal voice that says "I can't actually fix anything so I might as well not try." Teshuvah calls us to take action to preserve and uphold human dignity and human rights, to love the stranger for we were strangers in the land of Egypt, to do what we can to build a more just and righteous world.

If we want to know what we would have done during the Civil Rights movement, we have an opportunity to do it now. That's the antidote to relentless bad news and overwhelm. That's how we make teshuvah. That's the turn to which this season calls us.

Be brave enough to envision a world better than the one we know now. And then set your hands to bringing that vision to life. That's the work, and this year it feels more critical than ever. As our sages remind us, it's not incumbent on us to finish the task, but neither are we free to refrain from beginning.

Shanah tovah.

This year my shul's theme for the Days of Awe is Vision. My sermons reflect and refract that theme in different ways.

Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.

August 5, 2018

Descent for the sake of ascent

This is the sermon I offered this morning at Rensselaerville Presbyterian Church. You can read other sermons in their summer sermon series here. This year's theme is "And still we rise."

This is the sermon I offered this morning at Rensselaerville Presbyterian Church. You can read other sermons in their summer sermon series here. This year's theme is "And still we rise."

In Hasidic tradition -- in the Jewish mystical-devotional tradition that arose in Eastern Europe in the late 1700s -- there is the concept of yeridah tzorech aliyah. "Descent for the sake of ascent." We experience distance from God in order to draw close. We fall in order to rise.

The term "fall" may have connotations here, in this Christian context, that I don't intend. I'm not talking about the Fall of Man, with capital letters, as I understand it to be interpreted in some Christian theologies. Judaism doesn't have a doctrine of original sin. I'm talking about something more like... falling down. Falling short. Falling away.

The paradigmatic example of descent for the sake of ascent is the narrative at the end of the book of Genesis that we sometimes call "the Joseph novella." We just heard a piece of that story this morning, so here's a recap for those who need it. Jacob had twelve sons, and his favored son was Joseph, for whom he made a coat of many colors. Joseph had dreams of stars bowing down to him, sheaves of wheat bowing down to him, and his dreams made his brothers angry, and as a result they threw him into a pit. He literally went down. And then he was sold into slavery in Egypt, and the verb used there is again he went down: in Hebrew one "goes down" into Egypt and "ascends" into the promised land.

In Egypt, he fell from favor with Potiphar and went down into Pharaoh's dungeon. And there he met the two servants of Pharaoh for whom he interpreted dreams, and he ascended to become Pharaoh's right-hand man.

And because of those things, he was in a position to rescue his family from famine, thereby setting in motion the rescue of what would become the entire Jewish people. Descent for the sake of ascent.

His descendants would become slaves to a Pharaoh in Egypt for 400 years. Finally our hardship was too much to bear, and we cried out to God. Torah tells us that God heard our cries and remembered us and brought us forth from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. Because we were low and we cried out, God heard us and lifted us out of there: descent for the sake of ascent.

Coming forth from slavery was the first step toward Jewish peoplehood; receiving Torah at Sinai, and entering into covenant with God, was the event that formed us as a people. Our enslavement led to our freedom which led to covenant and peoplehood: descent for the sake of ascent.

The summer season on the Jewish calendar mirrors this same trajectory. Just a few weeks ago we marked the day of communal mourning known as Tisha b'Av, the ninth day of the lunar month of Av, the lowest point in our year.

On Tisha b'Av, we remember the destruction of the first Temple in Jerusalem at the hands of Babylon in 586 BCE. We remember the destruction of the second Temple in Jerusalem at the hands of Rome in 70 CE. We remember the start of the Crusades, the expulsion from the Warsaw Ghetto, an incomprehensibly awful litany of communal tragedies that have all, somehow, against all odds, befallen us on or around that same calendar date. On Tisha b'Av we fast, we hear the book of Lamentations, we read poems of grief, we dive deep into the world's sorrow and suffering and brokenness.

And, Jewish tradition says that on Tisha b'Av the messiah will be born. Out of our deepest grief comes the spark of redemption. And every year Tisha b'Av is the springboard that launches us toward the Days of Awe, the Jewish new year and the Day of Atonement, of at/one/ment. Authentic spiritual life demands that we sit both with life's brokenness and life's wholeness. A spirituality that's only "positive," only feel-good, isn't real and isn't whole. When we sit with what hurts, that's what enables us to rise. Descent for the sake of ascent.

The Hasidic master known as the Degel Machaneh Efraim teaches that ascent and descent are intimately connected. When a person falls away from God, the experience of distance from the Divine spurs that soul's yearning to return. Falling down is precisely the first step of rising up. Our mis-steps are precisely what spur us to course-correct and adjust our path. Descent for the sake of ascent.

Looking at the world around us, it's easy to feel that everything is falling apart. Migrant children torn from the arms of their parents and imprisoned in cages. Hate crimes on the rise. People of color killed by police who are supposed to be sworn to protect. Incidents of prejudice increasing: against religious minorities, and against transgender people, and against people of color. Our political system seems to be broken. International relations seem to be broken. There is brokenness everywhere we look.

Our work -- the spiritual work of this moment in time -- is twofold. One: we have to resist the temptation to paper over the brokenness with platitudes and pretty words, "God has a plan," or "everything's going to be okay." My theology does not include a God Who sits back and allows rights to be stripped away for the sake of some greater plan we don't have to try to understand. And two: we have to face the brokenness, even embrace the brokenness, and let it fuel us to bring repair. We have to make our descent be for the sake of ascent.

When we feel our distance from the divine Beloved, there's a yearning to draw near. Our hearts cry out, "I miss Your presence in my life, God, I want to come back to You." Or in the words of psalm 27, the psalm for this season on the Jewish calendar, "One thing I ask of You, God, this alone do I seek: that I might dwell in Your house all the days of my life!"

When we feel our distance from the world as it should be -- a world where no one goes hungry, where bigotry has vanished like morning fog, where every human being is uplifted and cherished as a reflection of the Infinite divine -- we yearn to bring repair. When we feel what's lacking, we ache to fill that void. Feeling how far we've fallen is precisely what spurs us to seek to rise. This is built into the very order of things. And that's where I find hope during these difficult days.

This is the work of spiritual life as I understand it. There are times that feel like a descent into the pit, a fall away from God, even imprisonment in Pharaoh's dungeon. This is true both on the small scale of every individual human life, and on the broader canvas of the nation or the world at large. But the thing about hitting bottom is, there's nowhere to go from there but up.

Our job is to inhabit every broken place, every spiritual exile, and let them fuel us to ascend closer to God and closer to the world as we know it should be. Then those who have sown in tears will reap in joy. Then those who went out weeping, carrying the seeds of the tomorrow in which they could barely find hope, will return in gladness bearing the abundant harvest of everything they need. Kein yehi ratzon: so may it be.

July 29, 2018

A summer Sunday in Rensselaerville (all are welcome)

I've never been to the First Presbyterian Church in Rensselaerville, NY, but their all are welcome page makes me love them already. I'll be worshipping with them next Sunday, August 5, because I've been invited to preach.

How does it come to pass that a rabbi will be preaching from their lectern? It turns out I'm far from the first to do so. Every summer they they welcome clergy and religious folks of different faiths to bring spiritual sustenance to their community. They've been doing that for more than 100 years:

For a short period in the second half of the 19th century, the village of Rensselaerville was a lively industrial town as the first site of the Huyck Woolen Mills. When mill founder and Presbyterian Church member F. C. Huyck Sr. moved his mill to Albany, he did not sever ties with the village or the church. But as jobs left with the mill so did many of the village residents, leaving the church without enough members to maintain a year-round pastor. The church continued because the Huyck family returned to Rensselaerville each summer to vacation and provided for a pastor during their stay.

F.C. Huyck Sr.’s granddaughter Katharine Huyck Elmore expanded the vision of the summer services, in the mid-20th century, to encompass various faith traditions and invited ministers, rabbis, priests, nuns and other preachers to bring their messages of compassion, social justice and stewardship of the world and community to our pulpit.

Their theme for this summer is "And still we rise" (after "And still I rise" by Maya Angelou), and everyone who's preaching there during the summer season is offering a reflection on that theme.

They asked me a few months ago to give them the title for my sermon. While I often struggle to come up with sermon titles (usually I write the sermon first and then figure out whatto call it), in this case I knew right away that I would call my remarks "Descent for the Sake of Ascent." I will draw on Torah, Hasidic tradition, and the unfolding of the Jewish sacred calendar to offer hope, strength, and consolation appropriate for listeners of any faith.

Worship begins at 11am. If you're in or near Rensselaerville next Sunday, I hope you'll join us.

July 26, 2018

The ties that bind

Going through a box of old papers and photographs in my parents' garage, I unearthed an embroidered velvet bag. Inside it was a set of tefillin -- old and worn, with straps that are thin both in diameter and in heft. One of the batim (the little houses that hold the scrolls) was partially crushed, and one of the retzuot (the straps) had broken into two pieces.

Going through a box of old papers and photographs in my parents' garage, I unearthed an embroidered velvet bag. Inside it was a set of tefillin -- old and worn, with straps that are thin both in diameter and in heft. One of the batim (the little houses that hold the scrolls) was partially crushed, and one of the retzuot (the straps) had broken into two pieces.

I was amazed. I went upstairs to find my father. The initials on the bag could be his: were these his tefillin?

"I don't think so," he said. "I don't recognize them. I don't think I've ever seen that bag before. Besides, mine are in my bedside drawer."

We went to his bedside table and sure enough his own tefillin were there, in their velvet bag, just as he thought... along with yet another set of tefillin!

"These are mine," he said, taking his own set briefly out of their case, "and I don't think I've put them on since my bar mitzvah! But I have no idea where this third set" -- the other ones in the back of his drawer -- "came from either."

This third set of tefillin has no bag or carrying case. Unlike the ones in the embroidered bag, which are clearly damaged, these seem to be intact. They show some signs of age, but the retzuot feel firm and the batim feel solid.

After some reflection, he decided that the third set -- the one in better shape -- probably belonged to his father Israel Barenblat z"l, and the ones in the velvet bag might have belonged to his grandfather Benjamin Barenblat z"l. But we can't be certain. We don't know the origins or original owner of either set.

I didn't bring my tefillin on this trip. Holding these -- especially the seemingly-intact third set -- made me yearn to put them on. So I said the blessings and wrapped myself in them.

Was it my imagination, or did I feel a pulse of energy coming through them, a zetz of connection with whichever ancestor once owned them?

They definitely felt unfamiliar. My own tefillin were brand-new when they were given to me thirteen years ago. They are a different size than these, and their straps feel different beneath my fingers and on my arm. But even though these were clearly not my tefillin, they felt good on my body. As tefillin always do, they activated my awareness of connection with God -- always thrumming beneath the surface. I sat in them for a moment, and said the shema silently, and marveled, and then took them off.

Both sets are coming home with me, and I'm already making inquiries with my friend Rabbi / Sofer Kevin Hale to see if he will check them and make repairs as necessary. Maybe one of these sets will pass to my son when he becomes bar mitzvah.

For now, I'm traveling home with the family tefillin safely tucked into my carry-on. I'm thinking about my family and its generations. I hope my ancestors to whom these once belonged would be happy to know that their tefillin have found a new home with their descendant the rabbi, even if my rabbinate would have been unimaginable to them.

Whenever I visit my birthplace and my parents I expect to come away with a renewed sense of connection to where I come from. But these tefillin crystallize that connection in a beautiful and unexpected way. I am grateful.

An early Shabbat shalom to all who celebrate.

July 24, 2018

Family bikkur cholim

The mitzvah of bikkur cholim, visiting the sick, is said to have originated with the Holy One of Blessing. When God visits Avraham by the oaks of Mamre in the heat of the day, that's understood to mean not just the literal heat of afternoon but the internal heat of fever. God visits Avraham as Avraham is recovering from his circumcision. In visiting the sick, we emulate God.

The mitzvah of bikkur cholim, visiting the sick, is said to have originated with the Holy One of Blessing. When God visits Avraham by the oaks of Mamre in the heat of the day, that's understood to mean not just the literal heat of afternoon but the internal heat of fever. God visits Avraham as Avraham is recovering from his circumcision. In visiting the sick, we emulate God.

Another teaching, this one from the Gemara, holds that the Shechinah -- the immanent indwelling divine Presence -- hovers over the head of the sickbed like a mother bird protecting her young. God's Presence is with those who are ill, whether they are aware of it or not. When we visit those who are sick, we enter into the divine Presence. The sickbed is a sacred space.

When we visit those who are ill, it's not our job to offer explanations for why we think they are sick, or tell them why their illness isn't so bad, or tell them how to feel about however they are. It is our job to be present, be kind, be ready to listen. To hold space for whatever they want or need to say. To take their cues about what they want to discuss. To let them rest when they need to.

And... all of these responsibilities may become more difficult if the person one is visiting is part of one's family. We all have roles that we play in our family systems: caregiver, rescuer, mediator, truth-teller, clown, the one who cheers people up, the one who picks fights, the one who makes peace. When someone is ill, those roles and their familiarity may lock old patterns in place.

Part of the work of bikkur cholim with one's own family is cultivating compassion for oneself amid the inevitability of sliding into those old roles. If you are visiting a family member who is ill, cultivate kindness both toward the person you are visiting, and toward your own neshamah (your own soul) as you do the visiting. You too are likely to need some gentleness and care.

For anyone who's doing the work of bikkur cholim, it's important to seek out a trusted friend, or rabbi, or spiritual director with whom you can process whatever comes up for you. Don't burden the person who is sick with responsibility for your reaction to their illness. Emotional reactions are normal! Don't be afraid to lean on your own support network before and after you visit.

It is natural to want to "fix" things -- especially if the person you are visiting is a member of your family. And... making things better is not your job. No matter what. The best gift you can offer is your presence, and your attentiveness to their needs. And you can best tend to the one who is sick if you're attentive also to your own needs for solitude and downtime and care.

Related:

Praying for what's possible, 2014

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers