Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 70

September 17, 2018

When (not) to forgive

"Rabbi, is it ever okay not to forgive?"

"Rabbi, is it ever okay not to forgive?"

That question comes my way every year around this season. (I've written about this before.) I find that it is asked most often by women, who may face (as women, and as Jews) a double whammy of cultural messages instructing us to be forgiving even at our own expense. But people across the gender spectrum struggle with this question.

Many of us know the teaching from Rambam (in his Hilchot Teshuvah, "Laws of Repentance / Return") that when someone has wronged another person, the one who committed the wrong must make teshuvah and seek forgiveness, and the one who was wronged is obligated to forgive. "Obligated" is a strong word. Is it ever okay, Jewishly, not to forgive?

Short answer: yes. Yes, Jewishly speaking, there are times when it is ok not to extend forgiveness. Longer answer: when the person who wronged you has not made teshuvah (more in a minute abut what that means, and what is implied therein) not only are you not obligated to forgive them, but one could even make the case that granting forgiveness in that circumstance is forbidden. Because if you were to forgive under that circumstance, without their teshuvah, your forgiveness would give cover to the unethical behavior not only of harming you in the first place, but also of choosing not to make teshuvah.

A reminder: teshuvah, which is often translated as "repentance," comes from the root that means turning or turning-around. Teshuvah is the work of turning oneself around, turning oneself in the right direction again, turning over a new leaf, re/turning to God and to the state of righteousness to which we are all expected to aspire. When we miss the mark in our relationship with God, we can make teshuvah and repair the broken relationship. When we miss the mark in our relationships with each other, we can make teshuvah and (maybe) repair the broken relationship. Repair may not be up to us. But our own teshuvah work is.

Here's Rabbi David J. Blumenthal, in his essay Is Forgiveness Necessary?

If the offender has done teshuvah, and is sincere in his or her repentance, the offended person should offer mechilah; that is, the offended person should forgo the debt of the offender, relinquish his or her claim against the offender. This is not a reconciliation of heart or an embracing of the offender; it is simply reaching the conclusion that the offender no longer owes me anything for whatever it was that he or she did. Mechilah is like a pardon granted to a criminal by the modern state. The crime remains; only the debt is forgiven.

The tradition, however, is quite clear that the offended person is not obliged to offer mechilah if the offender is not sincere in his or her repentance and has not taken concrete steps to correct the wrong done...

The principle that mechilah ought to be granted only if deserved is the great Jewish "No" to easy forgiveness. It is core to the Jewish view of forgiveness, just as desisting from sin is core to the Jewish view of repentance. Without good grounds, the offended person should not forgo the indebtedness of the sinner; otherwise, the sinner may never truly repent and evil will be perpetuated. And, conversely, if there are good grounds to waive the debt or relinquish the claim, the offended person is morally bound to do so. This is the great Jewish "Yes" to the possibility of repentance for every sinner.

If the person who wronged you has done teshuvah and is sincere in their repentance, then tradition asks you to forgive. But that's a big 'if.' How can you tell if the person's teshuvah is sincere? My own answer relies on a combination of factors. For starters, the person who wronged you has to actually apologize (and I mean a real apology.) Ideally that apology should feel sincere to you. But the person's subsequent actions are of greater importance. Saying sorry isn't enough: they also have to take concrete steps to correct the wrong, and they have to show with their actions and their choices that they have changed.

One rubric says that we can tell if teshuvah is genuine when the person making teshuvah has the opportunity to commit the same misdeed as before, but this time makes a different choice. (That's Rambam again.) Imagine that I harmed you physically by driving over your foot. I would need to not only apologize to you for hurting you, and do what I could to correct the wrong (giving you an aspirin, or perhaps a pair of steel-toed boots?), but also, the next time I was driving my car near where your foot was resting, I'd need to notice your foot, make a conscious choice not to drive over it, and then follow through with that choice.

But if my apology to you felt insincere -- "Whatever, you're overreacting but I'm sorry you're upset" -- you would be under no obligation to forgive me for the harm. And if I didn't do what I could to make up for having driven over your foot, ditto. And if I didn't take steps to ensure that I never drive over your foot again, ditto all the more. (It's a ridiculous example, I realize. I use it because it lets me illustrate the principle I want to communicate, without getting into the kinds of hypotheticals that might evoke or re-activate the interpersonal traumas that bring people to me with these questions about forgiveness in the first place.)

If someone has harmed you -- whether in body, heart, mind, or spirit -- and they come to you seeking forgiveness, you're allowed to take the time you need to discern 1) whether their apology is genuine, and 2) whether they have done all that they could to remedy the damage, and 3) whether they have done the internal work of becoming a person who would no longer harm you in that same way given the opportunity to do so again. If the answer to any of those questions is no -- and kal v'chomer (all the more so) if they don't apologize in the first place -- then you are not obligated to forgive them for harming you.

Emotionally and spiritually, pay attention to what your heart and soul are saying. If your heart and soul resist the idea of forgiving someone, discern whether that resistance is a case of holding on to an old resentment that you'd be better off releasing -- or whether it's a case of healthy self-protection. If offering forgiveness would serve you, then I support that. But Jewish tradition does not require us to re-inscribe the harm done to us by forgiving our abusers. And as Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg notes in her excellent twitter thread on this, the person who needs to repent can do so whether or not the person they harmed forgives.

And on that note... here's a Prayer for those not ready for forgive by my friend and colleague Rabbi Jill Zimmerman.

G'mar chatimah tovah: may we all be sealed for goodness in the year to come.

September 15, 2018

Revising the poem: a d'varling for Shabbat Shuvah

וְעַתָּ֗ה כִּתְב֤וּ לָכֶם֙ אֶת־הַשִּׁירָ֣ה הַזֹּ֔את וְלַמְּדָ֥הּ אֶת־בְּנֵי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל שִׂימָ֣הּ בְּפִיהֶ֑ם

Therefore, write down this poem and teach it to the people of Israel; put it in their mouths... (Deut. 31:19)

וַיִּכְתֹּ֥ב מֹשֶׁ֛ה אֶת־הַשִּׁירָ֥ה הַזֹּ֖את בַּיּ֣וֹם הַה֑וּא וַֽיְלַמְּדָ֖הּ אֶת־בְּנֵ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃

That day, Moses wrote down this poem and taught it to the Israelites. (Deut. 31:22)

These are two verses from this week's Torah portion, Vayeilech.

The classical commentators have various theories on what it means that Moshe wrote down "this poem." Does that mean that on that day, Moshe wrote down the entire Torah? Does it mean that he wrote down some specific fragment of Torah, from this verse to that verse, but not the whole thing? I admire their commitment to detail. But what strikes me is the fact that Moshe uses the word poem in the first place.

To be sure, there are portions of Torah that are clearly poetry. Some of them are even written on the scroll in unusual ways -- like the Song at the Sea, a very ancient poem that is written in an interlaced pattern that evokes brickwork, or perhaps the waves of the sea. But over the course of this week's Torah portion, Moshe refers to what he's saying sometimes as a Torah, which we could translate as a Teaching; and sometimes as a שירה / shirah, which is the Hebrew word for poem.

Moshe seems to be saying that the entire Torah is, in some way, a poem.

When I was a chaplaincy student, during my first year of rabbinical school, I learned to think of hospital room visits as opportunities to encounter the "living document" of a human soul, the Torah of our lived human experience. Each life is a Torah, and delving in to the meanings we find in our lives is a kind of Torah study.

Of course, our tradition mirrors that metaphor in the Unetaneh Tokef prayer we recite on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, which describes the Book of Memory opening. That Book "reads from itself and the signature of every human being is in it." We write the Book of Memory with our every choice, our every action, our every word.

Moshe says the Torah is a poem. And my chaplaincy supervisor taught that each human life is a Torah, a book that we write with our actions and our choices, worthy of study. From these two teachings, I come to the inescapable conclusion that each human life is, therefore, a poem.

Here's a thing I know about poetry: it benefits from revision.

We live in linear time, which means we can't revise the actions and choices we made yesterday -- we can't go back in time and edit out the things we now regret having said or done, or left unsaid or undone. But we can revise ourselves. We can revise our habits and our hearts. Indeed: that's precisely what the work of teshuvah is about.

If there were ever a time to look at the poem of our lives and figure out where we need to revise and reshape, now is that time. It's Shabbat Shuvah, the Shabbat of Return. I want to offer an alternative name for this Shabbes, in keeping with our Vision theme for the Days of Awe this year: the Shabbat of Revision. Re-Vision: seeing ourselves anew. Revising ourselves into a new form. That's the work of teshuvah, and it is always open to us.

The poem of your life is in your hands. How will you revise yourself this year?

Teshuvah

God and I collaborate

on revising the poem of Rachel.

I decide what needs polishing,

what to preserve and what to lose;

God reads my draft with pursed lips.

If I really mean it, God

sings a new song, one strong

as stone and serene as silk.

I want this year’s poem

to be joyful. I want this year’s poem

to be measured like flour,

to burn like sweet dry maple.

I want every reader

to come away more certain

that transformation is possible.

I’d like holiness

to fill my words

and my empty spaces.

On Rosh Hashanah it is written

and on Yom Kippur it is sealed:

who will be a haiku and who

a sonnet, who needs meter

and who free verse, who an epic

and who a single syllable.

If I only get one sound

may it be yes, may I be One.

This is the d'varling I offered at my shul this morning. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.) The poem was written in 2004 and can be found here, along with my other new years' poems.

September 13, 2018

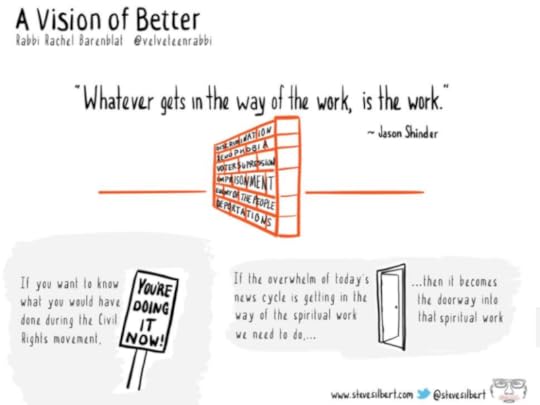

A Vision of Better: sketchnote edition

Deep thanks to Bayit Builder Steve Silbert for his sketchnote of my Rosh Hashanah sermon, A Vision of Better.

What death helps us see: a sermon for Yom Kippur morning

This is not my beautiful sermon. (Do you know that Talking Heads song? "You may ask yourself, how did I get here? ... You may tell yourself, this is not my beautiful house. This is not my beautiful wife." Well: this is the time of year for asking ourselves, how did I get here? And this is not my beautiful sermon.)

This is not my beautiful sermon. (Do you know that Talking Heads song? "You may ask yourself, how did I get here? ... You may tell yourself, this is not my beautiful house. This is not my beautiful wife." Well: this is the time of year for asking ourselves, how did I get here? And this is not my beautiful sermon.)

I wrote a beautiful sermon for Yom Kippur morning. I started it weeks ago. It's clean, and clear, and polished. It's about the lenses we wear, the habits and perspectives and narratives that shape our view of the world. It's about how this is the time of year for recognizing our lenses and cleaning them, and how that's the work of teshuvah. It fit perfectly with this year's theme of Vision. I spent hours tinkering with it, reading it out loud, refining every phrase.

And then last week I threw it away. Because it doesn't feel urgent. And if there is anything that I can say with certainty, it is that this is a day for paying attention to what's urgent.

I spoke last year about how Yom Kippur is a day of rehearsal for our death. I spoke about the instruction to make teshuvah, to turn our lives around, the day before we die. Of course, none of us knows when we will die: so we need to make teshuvah every day.

There are all kinds of spiritual practices for that. Before sleep each night we can go back over the events of the day, and discern where we could have done better, and cultivate gratitude for the day's gifts, and make a conscious effort to let go of the day's grudges and missteps. I try to do those things, most nights. And precisely because I try to do those things every day, they don't feel especially urgent, either. They're part of my routine soul-maintenance, the spiritual equivalent of brushing my teeth.

If you knew you were going to die tomorrow, what sermon would you want to hear from me today? Okay, in fairness, if you knew you were going to die tomorrow, you might not be in synagogue today. But humor me. Imagine that somehow, against all odds, you received a message from the Universe that tomorrow you were going to die. What would you want to spend today thinking about, and feeling, and doing? If you knew you were going to die tomorrow, what might you suddenly see?

If I knew I were going to die tomorrow, I would want to spend today telling everyone that I love exactly how much I love them. I would lavish my child with all the love I could manage. I would hug my friends. I would call my parents and my siblings. I would write endless love letters to people who matter to me, and I would tell them in no uncertain terms that they are beautiful, extraordinary, luminous human beings and that I am grateful for them to the ends of the earth and beyond.

That tells me that once I remove my ordinary lenses and look at the world as though this moment could be my last, one of the things that matters to me is my capacity to love.

If I knew I were going to die tomorrow, I would write a long, probably overly-detailed, probably rambling ethical will telling my child all of the qualities I hope he will grow up to inherit. I would write about how I hope that he will always be curious, and kind, and thoughtful, and empathetic. I would write about how I hope he will travel the world with interest in its cultures and its inhabitants. I would write about how I hope that he will always be ready and willing to talk to God, and to learn about how others talk to God. I would write about how important it is to care for the vulnerable, to share our abundance with those who have less, to stand up for dignity and human rights, to use his privilege to help others who are less fortunate than he.

That tells me that once I remove my ordinary lenses and look at the world as though this moment could be my last, Jewish values matter to me. The value of standing up for what's right, the value of loving the stranger and protecting the vulnerable, the value of deep ecumenism and learning both from and with those on other spiritual paths.

If I knew I were going to die tomorrow, I would cook foods that I love and I would share them with people in my life. Many of us are fasting today, so I'll spare all of us the description of that multi-course meal. But I would choose foods that remind me of people and places and adventures and conversations. I would not count calories. I would seek to nourish others with the creations of my hands. I would seek to savor every bite, and I would sing the Grace After Meals with gratitude and gusto.

I would call up people with whom I have sung over the last twenty-five years and sing with them again. Over zoom or Facetime, if I had to. Anything to touch, again, the sense of holiness I find when our voices mingle into more than the sum of their parts.

I would make sure my will was in order. I would think about how best to give things away. What worthy causes could I support with some of my dollars if my life were going to end tomorrow?

I would ask a friend to teach me something new: a new insight, a new Hasidic master's take on a piece of Torah, a new snippet of Zohar, a new poem.

I would enjoy every little thing I could find to enjoy, from a hot shower to a cup of coffee to gazing at the twilight sky or the stars.

If I knew I were going to die tomorrow, I wouldn't email people who have hurt me or betrayed me or damaged my trust to invite them to make amends on my last day of life. Because it's possible that I'd be doing that to serve my own ego needs. Besides, I wouldn't want to spend my last day on earth rehashing old wounds. Instead, I'd do my best to make my peace with the fact that there are people who have hurt me and aren't going to apologize, and then I'd do my best to let it go.

I wouldn't watch cable news or refresh Facebook and Twitter endlessly, because if this were my last day in this life, there would be better ways to spend it.

I might write a poem, though I can't tell you what it would be about. Not because it's a secret, but because I don't myself know. Though this afternoon during our break I might take a few minutes to meditate on this, and then see what kind of poem arises.

So far I've mentioned mostly joyous things I would do if I knew I were going to die tomorrow. But let's be real: I would also be angry and sad. Angry about all the things I still wanted to do. Sad about the time with loved ones that I had hoped was still ahead of me. Sad about all the moments I would miss, in my child's life and the lives of those whom I love.

I would fall on the neck of someone who matters to me, probably several someones who matter to me, and I would wail: what was it all for, if it was just going to end so quickly? And then when my internal storm had passed, I would answer my own question: we don't get to know how long we're here for. No one is promised fourscore and ten. And my best understanding of what we're here for is to become, and to connect, and to care for each other, and to love. And that's true whether I get one more day, or fifty more years.

That's what I see, when I imagine how impending death would strip away my roles and my responsibilities and my to-do lists -- the lenses through which I usually see the world.

When our sages said today was a rehearsal for our death, they didn't just mean that when we go without food and drink it's as though we were no longer alive, or that when we wear white it's as though we were wearing our burial shrouds. They meant, wake up! You could be dead tomorrow. In light of that, what do you see?

The fact that we will die is a clarifying lens. Most of the time we ignore our mortality, because when we realize we are going to die our hearts open wide, and it's hard to live in the world with hearts and souls that are so tender. But today is the day to recognize that we will die, and notice what snaps into clear focus when we sit with that truth. Because whatever that is, is what's really important to us.

I could be dead tomorrow. In light of that, a lot of the things I fixate on don't matter much.

The brokenness of the world does still matter. Systemic injustice does still matter. Bigotry and prejudice and racism and misogyny and homophobia and antisemitism do still matter, and if I were going to die tomorrow, I would grieve the fact that I hadn't done enough to try to eradicate those things. I would grieve the fact that I had wasted any minutes of this life mired in things that are unimportant instead of working toward justice and increasing the world's amount of love. And then I would try to find a few last things I could do, on that last day of my life on this earth, to bring about more justice and more love -- the two qualities in whose perfect balance we imagine God.

I wear a bracelet that says, on one side, אנכי עפר ואפר, "I am dust and ashes," and on the other, בשבילי נברא העולם, "for my sake was the world created." This koan comes to us from Rabbi Simcha Bunim, and both of these statements are always true.

On the one hand: I am dust and ashes. We all are. When Torah teaches that the first human being was molded from the clay of the earth, it's offering a poignant reminder that when our bodies die, we melt into the soil from which that poetic text says we came. And on the proverbial other hand, this world was made for me. This world was made for each one of us, each precious human being, and each of us is a reflection of Infinity.

Make teshuvah on the day before your death doesn't mean "email the people you might have angered last year, just in case you kick the bucket tonight." It means we never know how much time we have. It means wake up and use the time you have. It means imagine that you might die tomorrow, and notice all of the hopes and dreams and regrets that come up -- and then work with those hopes and dreams and regrets. It means imagine that you might die tomorrow, and notice the ache of what would be left un-done, and then do it.

It means give love freely to the people in your life who deserve it. It means life is too short to give energy to people who harm you. It means don't be afraid to feel, don't be afraid to laugh, don't be afraid to weep. It means take risks, tell other people what matters to you, let yourself be vulnerable. It means what are you so afraid of: if dying is inevitable, what's so bad about making mistakes, or looking ridiculous, or taking the leap of saying "I love you"?

It means, as Mary Oliver asks:

The Summer Day

Who made the world? Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

This grasshopper, I mean --

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down --

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don't know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn't everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

—Mary Oliver

Ahavah

V'rachamim

Chesed

V'shalom.

אַהֲבָה

וְרַחֲמִים

חֶֽסֶד

וְשָׁלוֹם.

(Love, compassion, kindness, and peace.)

This year my shul's theme for the Days of Awe is Vision. My sermons reflect and refract that theme in different ways.

Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.

September 12, 2018

A Vision of Better: now in video

A few folks asked whether there is a video or audio recording of my sermon from Rosh Hashanah morning.

Here's video (and audio) -- taken from the synagogue's Facebook Live stream, so the quality isn't fantastic, but I'm happy to share.

(If you can't see the embedded video, you can go directly to it here.)

May our journey through these Ten Days of Teshuvah clarify our vision and strengthen us to do our work in the world.

September 9, 2018

Sweet

In the produce section

late peaches bump hips

with early apples

all of them blushing.

Summer and fall kiss

and then part, but

one of these days

summer's going to decide

it's time to let fall

spread its robe...

Where the seasons meet

the new year crowns.

Crisp apple slices bathe

in honey, liquid gold

like Torah's highest song.

May we all merit

this unabashed sweetness

replete and satisfied.

[L]et fall spread its robe... See Ruth 3:9.

Crisp apple slices bathe / in honey... A traditional food for the new year among many Ashkenazi Jews.

Torah's highest song... During the Days of Awe, the Torah is chanted with a special cantillation. The melody lilts and lifts, bringing heart and soul with it.

L'shanah tovah u'm'tukah -- here's to a good and sweet year.

September 6, 2018

Op-ed in the Berkshire Eagle: on protecting transgender rights and dignity

Thanks to the Berkshire Eagle for publishing my op-ed: Protect transgender rights and dignity.

Thanks to the Berkshire Eagle for publishing my op-ed: Protect transgender rights and dignity.

For those who can't get to the digital edition, I'm reprinting the op-ed here on my blog.

NORTH ADAMS — On Election Day this November, voters in Massachusetts will encounter a referendum on our state law that protects transgender people from discrimination and harassment in public places. A "yes" vote on Question 3 would uphold current law, which means transgender people would maintain the rights and dignity to which they are now legally entitled. A "no" vote on 3 would repeal current law, leaving transgender people vulnerable to discrimination in public places such as restaurants, stores, and hospitals.

As a rabbi, I'm horrified at the prospect of a repeal. I'm voting "yes" on 3 because I have transgender congregants, friends, and loved ones. Because repeal — denying transgender people's rights and dignity — would be counter to the religious values I hold dear. And because repeal would set precedent for the rest of the country, and would embolden bigotry in many forms.

Jewish tradition teaches that we are all made in the divine image. Judaism doesn't understand God to have a physical form (nor, for that matter, a singular gender; we speak of the Divine in terms that are masculine, feminine, and gender-neutral). We can glimpse the "divine image" through humanity's diversity of shapes and sizes, races, sexual orientations, and gender expressions. And because we're all made in the divine image, Judaism teaches that human rights and dignity are everyone's birthright.

My tradition also teaches that one reason why we trace human ancestry back to a single first person is so that no one should be able to say "my ancestors were better than yours" (or, its corollary, "I'm better than you"— or "I deserve to be served in this restaurant while you do not.") My religious values call me to proclaim the inherent rights and dignity of trans people.

Of course, given appropriate division between church (or synagogue) and state, I shouldn't expect any state to legislate based on my religious values. But the secular values we share as Americans also demand a "yes" vote on Question 3. All should be entitled to equal treatment under the law, regardless of gender identity. And all should have the right to be safe from discrimination and harassment in public places: no matter whether we are cisgender or transgender, no matter what our gender expression, no matter what pronouns we prefer.

This matters especially for transgender youth, including those who identify as nonbinary. I want to be able to truthfully tell transgender kids that we see them, and we value them, and we uplift and uphold them in all that they are. I want to be able to promise transgender kids that they will continue to be treated with dignity in coffee shops and movie theaters and doctors' offices, and that they can be who they are in the public sphere without fear. I want to be able to assure transgender kids that we who are old enough to vote will not strip away the protections to which current law entitles them.

I'm thankful to live in a state where people of all gender identities are protected from discrimination. Let's keep it that way. Join me in voting "yes" on 3 in November, and uphold human dignity for all.

Rabbi Rachel Barenblat serves Congregation Beth Israel in North Adams. She is a founding builder at Bayit: Your Jewish Home.

September 2, 2018

Building the Jewish future together

It’s an audacious idea – that a Jewish future needs to be built, or that we (or anyone) can claim the inner wisdom, the know-how, the tools, the chutzpah and even the right to do the building.

But if you’re reading this post, you’re part of that team – a growing circle of builders taking the Jewish future into your own hands. Because let’s face it: the Jewish future is in your hands.

This call to build isn’t a risk-averse negative – like shrill sirens wailing alarmist warnings of the “ever-disappearing Jew” – but rather a welcoming and realistic positive. The Jewish future will be exactly what people make it – nothing more and nothing less – so why not focus on the realities of building and builders?

That’s exactly what we aim to do. Welcome to Bayit: Your Jewish Home.

That's from the first post on Bayit's new blog, Builders Blog, written by my fellow founding builder R' David Markus. Read the whole thing: You're Building the Jewish Future -- Yes, You. (Illustration by builder Steve Silbert.)

September 1, 2018

What we choose to serve

Late in this week's Torah portion, Ki Tavo, there's a set of blessings and curses. Torah promises us that if we follow the mitzvot and walk in God's ways we will be blessed with abundance, and if we turn away we will experience curses. And then Torah says:

Late in this week's Torah portion, Ki Tavo, there's a set of blessings and curses. Torah promises us that if we follow the mitzvot and walk in God's ways we will be blessed with abundance, and if we turn away we will experience curses. And then Torah says:

Because you would not serve Adonai your God in joy and gladness over the abundance of everything, you shall have to serve -- in hunger and thirst, naked and lacking everything -- the enemies whom Adonai will let loose against you. (Deuteronomy 28:47-48.)

Some of us may struggle with the notion of a vengeful God Who would repay us for breaking faith in these ways. (That's certainly not my God-concept.) But what happens if we read the verse not prescriptively but descriptively? In other words: this isn't about what God will "do to us" if we turn away from the mitzvot. This is about the natural consequences of choosing to turn away from a path of holiness.

Does the idea of serving make us uncomfortable? Maybe we want to say, I'm nobody's servant -- I live for my own self! But in Torah's frame, that's an impossibility. Once we were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt and God brought us out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm: not so that we could be self-sufficient and serve our own needs, but so that we could enter into covenant with God and serve the Holy One.

Everyone serves something. That's a fact of human life. The question is what we will choose to serve, and how.

In Torah's understanding, either we can dedicate our lives to serving the Holy One of Blessing -- through the practice of mitzvot both ritual and ethical; through feeding the hungry and protecting the vulnerable; through cultivating gratitude for life's abundance; through working to rebuild and repair the world; through the work of teshuvah, turning ourselves around -- or we can turn our backs on all of that.

And if we turn our backs on all of that, says Torah, we will find ourselves serving a master who is cruel and uncaring. Maybe that master will be overwork. Maybe that master will be a political system that mistreats the immigrant and the refugee. Maybe that master will be whatever we use to numb ourselves to the brokenness around and within us.

But there really isn't any other choice. We can't choose not to serve. We can't choose to be completely self-sufficient and not bound in relationship -- that's not how the world works. In Torah's stark framing, either we can serve God or we can serve something else, and the inevitable fruits of serving something else will be disconnection and lack and facing down a slew of internal enemies.

This is not to say that if we are facing internal enemies like anxiety and depression, it's a sign that we've turned away from the mitzvot or turned away from God. Many of us are plagued by those internal adversaries, and I thank God for the abundance of tools at our disposal for helping us deal with them, from therapy to spiritual direction to all of the practices that can help us maintain an even keel.

Being servants of the Divine doesn't mean we'll be spared those challenges. But Torah says that if we turn away from the obligation to serve, we'll meet with what feels like enmity. If we turn away from the obligation to serve, we'll experience lack -- maybe because our needs won't be met, and maybe because we won't have cultivated the mindset that would enable us to feel grateful for what we have.

Choosing to serve God means choosing to be in relationship. It means choosing love, and choosing hope, and choosing ethical actions, and choosing spiritual practice, and choosing to work toward repairing both the broken world and our broken hearts. Choosing to serve God means choosing to be attentive both to the needs of others and to our own neshamot, our own souls.

As you walked into this sanctuary this morning you may or may not have noticed the words emblazoned over the doors: עבדו עת–ה׳ בשמחה / ivdu et Hashem b'simcha, "Serve God with joy." Over our ark is the other half of the verse from Psalm 100, באו לפניו ברננה / bo'u l'fanav birnanah, "come into the Presence with gladness."

The question I invite us to sit with this morning is this: what does it mean to serve the One with joy? Is the verse urging us to serve God and to do so joyously -- or to cultivate joy and make that a form of holy servive? And what would it feel like to come into the Presence with gladness: to feel in our hearts and know in our minds that we are surrounded and suffused with holy Presence, and to be glad?

What would it look like, what would it feel like, to do our teshuvah work from that place?

Shabbat shalom.

This is the d'varling that I offered at my shul this morning. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

August 29, 2018

A piece of mine in @929English

I've been really impressed recently with a new project called 929. Each weekday they share Torah insights and commentaries from scholars, clergy, artists, and more:

Each day, from Sunday to Thursday, you will land here on a new chapter, with the text of the chapter, an audio version, and many original materials about the chapter, including short posts with insights and comments, a playlist with several podcasts lessons on the chapter, a Hebrew Corner with a word of the day, and a helpful summary of the major points of the chapter.

(That's from their introduction to the site -- what it is, and how to use it.) The site exists both in a Hebrew edition and an English edition -- I'm linking here to the English edition but if you want to toggle to the Hebrew just click on the letters "HE" in the upper right-hand corner.

They're doing really great work -- which is why I was honored when they reached out to me to solicit a piece of mine. You can find it here: Dinah, the Silent Twelfth Child of Jacob. (Content warning: rape of Dinah.) My piece appears alongside a poem by Yakov Azriel, a screenplay by Nathan Lewin ("The State vs. Shimon and Levi"), an excerpt from Anita Diamant's retelling of the Dinah story, and more.

I hope you'll click through and spend some time at 929. It's a powerful collection of resources that will enrich our relationship with Torah.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers