Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 80

December 11, 2017

Nava Tehila at the #URJBiennial, and renewal everywhere

A glimpse of where and how I davened on Friday morning.

One of the highlights of my URJ Biennial was davening last Friday morning with Nava Tehila.

This is not surprising. Longtime readers of my blog know that davening with Nava Tehila has long been one of my favorite things in the universe, anywhere. Let's see: great music -- check. Deep heart-connection -- check. Awareness of the flow of the matbe'ah (the structure of the service) -- check. Attunement to body and to silence -- check. Balance of contemplative and ecstatic -- check. Davening with Nava Tehila feels like coming home.

I love how they set the worship space up, in concentric circles with space in the middle, a kind of emptiness echoing the ancient holy of holies. I love how Dafna and Yoel work (wherever they are) with a cadre of holy levi'im, musicians who aren't just accompaniment but are part of the active leadership team. I love their melodies and harmonies. And all of these add up to more than the sum of their parts. Every time I daven with Nava Tehila, I come away with my heart and soul feeling recharged, reconnected, and rejuvenated, and my body buzzing from the dancing and the joy.

It was neat to daven with them at a gathering explicitly created by and for Reform Jews, and to see that they don't change what they do in any way based on the denominational identity of the community with whom they're davening. And I know that last week they were at the USCJ, the big gathering of Conservative Jews, doing the very same kind of thing -- and, I'm guessing, meeting with every bit as much joy and enthusiasm and wow! as they heard from the Reform crowd on Friday morning.

When I say that renewal flows through all of the denominations, this is part of what I mean.

Colorful tallitot are everywhere, for instance. Not only the rainbow tallit that Reb Zalman z"l designed so many years ago, each color of the rainbow representing one of the seven "lower sefirot" or aspects of divinity -- though I saw a bunch of those at the Biennial, as I do everywhere! (And I'm guessing most people have no idea who designed that tallit or what its origins are -- though if you're interested, here's the story, which I love knowing.) But the very fact of multicolored tallitot was one of Reb Zalman's innovations in the first place, back in the 1950s. Now they're a natural part of Jewish prayer life almost everywhere.

And renewal melodies are everywhere. I can't tell you how often I've encountered a liturgical melody by Rabbi Shefa Gold -- come to think of it, we sang one on Friday night at the URJ Biennial before dinner in the ballroom where I was seated! Her melodies are known and sung across the Jewish world (and as with the tallitot, most people may not know where they come from -- it's easy for melodies to seem miSinai, as though we received them with Torah at Mount Sinai.) There are other renewal composers whose work is becoming part of the canon, too, like Shir Yaakov. And, of course, Nava Tehila, who share both their melodies and their way of davening not only in their Jerusalem home but in places they visit around the world.

Beyond the music, renewal modes of davenen (prayer) are everywhere. If you've ever been to a chant-based service, a contemplative service, a service that drew on Jewish meditative or mystical teachings, a service where people danced in the aisles, you've had a brush with some renewal ways of connecting with prayer. (I say "some" ways, rather than "the way," because there is no single way to pray in Jewish renewal. That's why as a renewal rabbinic student I was expected to learn how to lead prayer-ful worship using any prayerbook there is, from full-text to minimalist, across the denominational spectrum... and to pray not only with books and received liturgy but also with silence, and music, and the unfolding prayers of the heart.)

And the flow of renewal continues. Renewal as it's unfolding now contains elements of what came before, remixed in new ways. I see Svara: A Traditionally Radical Yeshiva as part of the flow of renewal. The Institute for the Next Jewish Future, the Jewish Emergent Network, the Kohenet Hebrew Priestess Institute are all part of the flow of renewal. (Some of these people and places may self-identify as part of the renewal of Judaism. Others might not choose the term "Jewish renewal" to describe what they do. But they're all part of renewal from where I sit.) Bayit: Your Jewish Home -- the new nonprofit organization I'm co-founding; stay tuned for more on that! -- is part of the flow of renewal. And so are many other places and spaces besides.

Renewal flows through all of the denominations, and in and through post-denominational and trans-denominational spaces, too. As software developers say, this isn't a bug, it's a feature. It isn't an accident or a mistake -- rather, it's part of renewal's core design. Renewal was never meant to be a denomination. Renewal is a way of doing Jewish, a way of approaching Judaism and spiritual life, that can enrich and enliven Jewish practice of all flavors. I've been saying that for years, but there was something extra-special for me (as a rabbi who serves a Reform-and-renewal shul) about living out that belief at the Biennial this year.

Related:

The capstone of my week: Kabbalat Shabbat with Nava Tehila (2016)

Visions of Renewal (2017)

Renewing Judaism (2017)

December 7, 2017

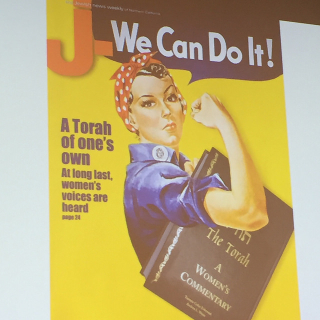

#URJBiennial 2017: Ten Years of the Women's Torah Commentary

In the shul that I serve, two editions of the Torah are tucked into the seats in our sanctuary. One is The Torah: A Modern Commentary, ed. by Gunther Plaut -- the standard (male-authored) commentary that appears in most Reform congregations. The other is The Torah: A Women's Commentary, ed. Eskenazi and Weiss, which came out ten years ago featuring entirely the commentary and voices of women.

In the shul that I serve, two editions of the Torah are tucked into the seats in our sanctuary. One is The Torah: A Modern Commentary, ed. by Gunther Plaut -- the standard (male-authored) commentary that appears in most Reform congregations. The other is The Torah: A Women's Commentary, ed. Eskenazi and Weiss, which came out ten years ago featuring entirely the commentary and voices of women.

I attended a session celebrating the book at the URJ Biennial featuring Rabbi Dr. Andrea Weiss, associate professor of Bible at the NY campus of HUC-JIR (also responsible for American Values and Voices) who served as associate editor of this book.

Rabbi Dr. Weiss began by explaining that the story of this volume started 25 years ago. Cantor Sarah Sager was invited to be the scholar-in-residence at a district biennial in Albany, and as she prepared her d'var Torah on Vayera she started to think about Sarah and asked a question that 25 years ago was a novel one: where was Sarah when Abraham took their son up the mountain?

She researched this, and discovered that she wasn't the first to ask the question, and that in fact people were beginning then to work in diverse fields to uncover and recover a more complex picture of women than the pshat (surface) Torah narrative suggests. But there was no organized, cohesive way to access this work. She ended her d'var Torah with the charge to commission the first feminist commentary to the Torah.

The leaders of the Women of Reform Judaism established a commentary committee that brought together rabbis, scholars, WRJ leaders and others. (We see a slide depicting the agenda for that gathering, including items like "Discussion of 'feminism, 'womanism' and other related terms." Wow.) The next step was a pilot project called Beginning the Journey: A Women's Commentary on Torah, edited by Rabbi Emily H. Feigenson, featuring the voices of HUC-JIR graduates. That book made clear, Rabbi Dr. Weiss says, that the way to move forward was to focus seriously on scholarship: women scholars in Bible, rabbinics, and other fields.

The editors were named; an editorial board was established (and oh, wow is it a "who's who" of amazing women in Biblical scholarship!); and they came up with the vision of a multivocal edition. For each Torah portion they would feature the Hebrew text, translation, commentary, a section called "another view" that offers another voice on the parsha, a post-Biblical piece, a contemporary reflection, and a section called "voices" which collects poetry and other creative responses. The intention was for the book to be definitively Jewish and definitively feminist, modeled in some way after Mikraot Gedolot which is always printed in editions that feature text surrounded by commentary.

Rabbi Dr. Weiss spoke about the diversity of the book's readership, and the extent to which it's been embraced across the denominations. She offers us a quote from Blu Greenberg:

Here are the voices of women from across the entire spectrum of Jewish life... although this work was initiated, funded, shepherded, overseen, edited, and largely produced by two extraordinary Reform Jewish scholars... it does not have the feeling of being owned by any one group, which explains why it has become the property of the whole Jewish people, as indeed any good commentary should.

It sounds like the book's creators have a sense now that what they did was historic -- in a way that wasn't entirely clear to them at the time. Rabbi Dr. Weiss says now that "The book translates feminist Biblical scholarship into a format that's useful for...laypeople and clergy of all genders." I agree.

Rabbi Dr. Weiss shared with us also an excerpt from this article by Rabbi Hara Person, Why Women’s Torah Commentary Matters Today More Than Ever Before. Rabbi Person writes:

The publication of The Torah: A Women’s Commentary was historic because when women become scholars and commentators of Torah, we take our rightful place in the sacred dialogue of text study, fulfilling the age-old Jewish responsibility of creating ongoing Jewish engagement and meaning. When women create a Torah commentary, we declare that the lives and experiences of the women of the Torah matter, and thus that the lives and concerns of contemporary women matter, too. This commentary stakes a claim for women in the narrative of our tradition and the sacred endeavors of our community, and in so doing, women are empowered to share their voices both within the Jewish community and in greater society.

I was also excited to hear from Dr. Ruhama Weiss (no relation to Rabbi Dr. Andrea Weiss!) that the book is now being translated both into Hebrew and into an Israeli women's culture idiom. There are plans afoot for an Israeli women's commentary that will feature some of what's in this book and also some of what's happening in Israeli women's commentary now.

Dr. (Ruhama) Weiss led us in a study of a poem by Nurit Zarchi called "She Is Joseph," touching on questions of feminist interpretation and women's representation in the Bible, and explored how our male sages responded to the story wherein Joseph resisted the advances of Potiphar's wife (and what their responses say about their own anxieties about masculinity and gender) -- a fabulous exploration, and the kind of Torah study that reminds me why I'm grateful this book exists.

December 5, 2017

Light in the darkness

Even in times of greatest darkness, when it seems that hope is gone, when you feel tapped-out and drained, when you have no more resources to draw on, when you've done everything you know how to do: don't give up. Do the tiny thing you can do, even if it doesn't feel like enough.

Even in times of greatest darkness, when it seems that hope is gone, when you feel tapped-out and drained, when you have no more resources to draw on, when you've done everything you know how to do: don't give up. Do the tiny thing you can do, even if it doesn't feel like enough.

That's the message of the Chanukah story. Not the tale of military victory (which doesn't appear in the Hebrew Scriptures anyway; the books of Maccabees are in some Christian Bibles, but not in ours), but the story of the oil that shouldn't have been enough. The story of the rededication of the Temple, the place where we connected with God. The story of the light that burned in the darkness even after it should have gone out.

The light that burned in the Temple in days of old was supposed to be kept burning all the time. From that comes the custom of the ner tamid, the "eternal light" that burns at the front of every synagogue now. The light (whether oil lamps of old, or today's LED lightbulbs) is meant to remind us of what's truly eternal: God's presence. Our connection with something greater than ourselves. Hope. Love.

Kindling the eternal light in the Temple when they knew they didn't have enough fuel to keep it burning was arguably foolhardy. But most leaps of faith look that way, until one takes them. And they so yearned to bring light into the world, to rekindle their reminder of divine Presence, that they kindled it anyway... and what shouldn't have been enough, became enough.

Maybe you're feeling lately like you're not enough. Maybe you're feeling like the world demands strength and perseverance that you can't seem to manage. Maybe you're feeling like the darkness presses in on all sides and will not be defeated. Maybe you're feeling worn-down and hopeless. For personal reasons, or for national reasons, or for global reasons, or all three at once.

Chanukah comes to remind us: don't give up. Don't give in to the voice that says you aren't enough. Do what little you can, even if it doesn't feel like it's enough -- maybe especially if it doesn't feel like it's enough. Make the leap of faith of continuing to try to build a life, a nation, a world that is better than the one we've got now. Start tonight, with one little light -- one tiny flame against the darkness. And tomorrow night there will be two. And the night after that there will be three.

Of course, it's not really about the candle flames. The literal flames on our chanukiyot are symbols. They remind us of a deeper spiritual truth: that we can bring light. That what we are is enough. That all hope is not lost. That when we can hope for better, we can work for better, and we can take back all of the places that have been desecrated and make them holy once again.

Related:

Mai Chanukah?, 2008

The obligation to sit still and notice, 2012

Be kind to yourself and remember that you are enough, 2014

(You can find all of my Chanukah-related posts in the Chanukah category.)

December 4, 2017

Rabbi Roundtable: what makes you proud to be a Jew?

In this week's Rabbi Roundtable, the Forward editors asked us, "What makes you proud to be a Jew?"

In this week's Rabbi Roundtable, the Forward editors asked us, "What makes you proud to be a Jew?"

I spoke about our approach to sacred time, our approach to renewed and renewing text study, and our drive to bring justice to the world.

Read all of our answers here: We Asked 20 Rabbis: What Makes You Proud To Be A Jew?

December 3, 2017

On Joseph, and faith in dark times: new commentary at My Jewish Learning

This week’s Torah portion takes us into the “Joseph novella,” which will continue through the rest of Genesis. As Joseph’s story begins, he’s tending sheep with his brothers and reporting on their behavior to their father Jacob. The Torah doesn’t tell us what exactly Joseph related to Jacob, or whether it was true, though the commentators Rashi (11th-century France) and the Radak (12th-13th-century France) suggest that his brothers were behaving unethically and treating each other poorly.

Joseph’s brothers hate him. In part because their father made him a fancy tunic. Joseph, for his part, is willing to name their ugly behaviors. And then, in what could be attributed either to arrogance or to naivete, he tells them his dreams — for instance, the one where their sheaves of wheat bow down to his. So they throw him into a pit and sell him into slavery...

...As a rabbi and spiritual director, one of my core questions is, “Where is God for you in this?” Spiritual direction invites us to discern divinity in whatever’s unfolding. But Joseph doesn’t need to be prompted with that query. Joseph feels God with him even while being unfairly maligned and punished. And because his sense of God’s presence is so strong, his sense of self isn’t shaken. That’s the quality in Joseph to which I most aspire: his deep connection with God...

That's from my latest Torah commentary for My Jewish Learning. Read the whole thing here: Joseph's Amazing Technicolor Faith.

December 2, 2017

The people who partner with God

In this week's Torah portion, Jacob is given a new name -- twice. Or maybe even three times. (It's the same name each time.)

In this week's Torah portion, Jacob is given a new name -- twice. Or maybe even three times. (It's the same name each time.)

The first time comes on the cusp of his meeting with his estranged brother Esau. He is alone; he wrestles all night; as dawn is breaking he tells his opponent "I will not let you go until you bless me," and the angel with whom he has grappled all night tells him his new name will be Yisra-El, Wrestles-With-God.

The second time comes later in the parsha. God appears to Jacob and says, "You whose name is Jacob: you shall be called Jacob no more, but Israel shall be your name." Then Torah reiterates the name yet again, adding "and thus, God named him Israel."

What's up with the triple reiteration of this name? One answer is that the redactor wasn't paying attention and he repeated himself, and said the same thing twice, and also conveyed something in multiple ways. But I think that's a cop-out. Our tradition invites us to find meaning in these repetitions. If Torah says it three times, it must be important. What is it telling us?

It's interesting that immediately after the third reiteration of Israel's new name, God introduces God's-self to Israel, saying, "I am El Shaddai; be fertile and increase, for nations will descend from you..."

Notice the juxtaposition of introductions. First God tells Jacob who Jacob is: one who wrestles with the divine. (This is one of our people's names to this day.) And then God tells Jacob who God is: אֵל שַׁדַּי / El Shaddai. In Hebrew, names have meanings: they aren't just sounds. So what does this divine name mean? "El" is pretty straightforward; it simply means "God." But "Shaddai" is less clear.

El Shaddai is often rendered as "God Almighty," but I'm not sure that's a good translation. Some argue that the word relates to mountains or wilderness. Others, that it relates to a root meaning "destroy." But in modern Hebrew, "shadayim" are breasts. I like to understand "El Shaddai" as a name that depicts God as the divine source of nourishment and flow. God as El Shaddai is the One Who nurses all of creation, Whose abundance flows like milk to nurture and nourish us.

In a related interpretation, Shaddai is seen as related to the word meaning "sufficiency" or "enoughness." (As in די / dai, "Enough!" -- or dayenu, "It would have been enough for us.") El Shaddai is the God of Enoughness, the One Who gives us everything we need and then some. Perhaps the name El Shaddai can remind us that we too -- made in the divine image -- are "enough" just as we are.

There's a sense of gender fluidity to this divine name, because "El" is a masculine word, and "Shaddai" (if you accept the shadayim connection) connotes femininity. Fluidity seems appropriate; after all, we call God the source of divine flow. The discipline of spiritual direction invites us to discern together where and how God's flow manifests in the life of each seeker. God flows into our lives in different shapes and forms.

El Shaddai is only one of our tradition's many names for God. The names we use for divinity change, as the faces of divinity we seek change. Sometimes we need God to be the All-Mighty, our defender. Sometimes we need God to be All-Merciful. Sometimes we need God to be Friend, or Beloved, or Parent. For me, the name El Shaddai is a reminder that I can relate to God as the nursing mother Who aches to bestow blessings.

As the sages of the Talmud wrote, "More than the calf wants to suckle, the cow yearns to give milk." More than we yearn and ache -- for love, for abundance, for sweetness -- God yearns and aches to give those things to us. Think of someone you deeply love, to whom you want to give every good thing. Feel how your heart goes out to them: you just want to give! The name El Shaddai describes a God Who feels like that toward us.

This piece of Torah reminds us who God can be for us -- and who we can be for God. The name Yisrael says it's our job to be in relationship with God. To dance, to push back, to waltz, to fight, to suckle: the wrestle takes many forms, but the relationship is always there. Even when we're angry with God, or when we feel as though God is angry with us, the relationship is there. The centrality of that relationship makes us who we are: the people Yisra-el, the people who partner with God.

Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.

Related: El Shaddai (Nursing Poem), 2009. (Also published in Waiting to Unfold, Phoenicia 2013.)

December 1, 2017

Biennial-bound again

Today I'm off to the URJ Biennial, the big gathering of the Reform movement.

Today I'm off to the URJ Biennial, the big gathering of the Reform movement.

The last time I attended a Biennial was 2005 in Houston, Texas. In 2005 I was a baby rabbinical student, only a few months into my first year of study. Now I've been a congregational rabbi for six years (and I served for five years before that as a rabbinic student intern alongside Reb Jeff!) I expect the Biennial is going to be a different experience for me this time around.

If you want a window into how I experienced the Biennial a dozen years ago, here's the roundup of the 18 posts I made during the 2005 Biennial. The internet was a very different place then. Twitter didn't exist yet. Facebook was a mere eighteen months old. We spoke in terms of the "blogosphere" and the "J-blogosphere" -- terms that make me sound like an internet dinosaur now! I don't know whether I'll blog much from the Biennial, though if something unfolds that feels appropriate to chronicle in this space, I'll do so.

There are a handful of sessions I'd particularly like to attend, and a handful of colleagues I'd particularly like to see. Beyond that, I'm keeping my schedule intentionally open so I can take advantage of whatever opportunities for learning, growth, and networking arise over the course of the next several days. If you'll be at the Biennial, drop me a line and let me know -- perhaps our paths will cross...

November 28, 2017

Rabbi Roundtable: Is there such a thing as Jewish values?

This week's installation of the Forward's Rabbi Roundtable asks, "Is there such a thing as Jewish values?"

This week's installation of the Forward's Rabbi Roundtable asks, "Is there such a thing as Jewish values?"

Many of us referenced the extent to which our "Jewish values" are universal. Several of us referenced the value of loving the stranger and seeing the inherent worth and dignity in every human being.

I spoke about the Jewish value of change, and the fact that our tradition is designed to continually be renewed.

Read our answers here: We Asked 21 Rabbis: Is There Such A Thing As Jewish Values?

November 25, 2017

Stick season

I used to own a long, soft, narrow-wale corduroy dress that always seemed to call to me around this time of year. Its colors were muted: taupe and pale purple and deep fir-green. One day I realized that it matched the Berkshire hills in their November colors: the taupe brown of bare trees seen from a distance, the muted purple of distant hillsides at early twilight, the deep green of conifers on the highest parts of the hills.

I used to own a long, soft, narrow-wale corduroy dress that always seemed to call to me around this time of year. Its colors were muted: taupe and pale purple and deep fir-green. One day I realized that it matched the Berkshire hills in their November colors: the taupe brown of bare trees seen from a distance, the muted purple of distant hillsides at early twilight, the deep green of conifers on the highest parts of the hills.

I rejoice when springtime paints the hills chartreuse. I relish the boldness of their summer green coats. I thrill to their yellow and orange autumn garb, though that beauty feels bittersweet because it presages the cold season to come. And now we're in the season I don't look forward to: "stick season," when the hills are bare and the nights are growing longer and plant life begins to go dormant because of the cold.

The challenge is finding the beauty in this spare, sere landscape -- because it is still beautiful. The hills reveal their contours in a different way. Other neighborhood houses, once hidden by stands of trees, become visible again. The grass gives up on being green and begins to turn pale wintery gold. Hints of red pop against this muted backdrop: old apples still left on the trees, berries nestled among the thickets of sticks.

In my mind I anthropomorphize our local plants and trees and bushes, imagining that they heave a sigh of relief when their performative season ends and they can rest. Okay, that's a stretch, but I know that the plants and trees that live here need to have a dormant season. It's as though the earth herself is taking a Shabbes: some downtime, some time when she doesn't have to produce (whether food or fruit or blossoms), some time when she can just rest and just be. Can I better learn that practice by paying attention to the world around me?

Instead of being (too) attached to any particular season's gifts, I want to learn how to seek the beauty in whatever the world around me presents. Right now my task is retraining my eye to notice the gifts of New England November: the subtle gradations of color, the delicate traceries of bare branches, the sweetness to be found in this gentle, muted visual palette. Mother Nature isn't always showy, but there's always something worth noticing, if I can maintain the practice of being willing to see.

November 21, 2017

One lesson from Talmud

The Forward's Rabbi Roundtable continues. This week's question was, "“If there is one lesson Jews today should learn from the Talmud, what is it?”

The Forward's Rabbi Roundtable continues. This week's question was, "“If there is one lesson Jews today should learn from the Talmud, what is it?”

Many of us said something about pluralism, diversity of voices, and embracing complexity. And more than one of us chose to cite the passage from Sanhedrin that notes that all humanity was created from a common ancestor so that no one should be able to say that they are better than everyone else.

Click through to read all of our responses: One Lesson Jews Today Should Learn From the Talmud.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers