Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 230

February 24, 2012

A d'var Torah for parashat T'rumah: on gifts, sanctuaries, and hearts

Here's the d'var Torah I'll be giving tomorrow at my shul -- so if you're coming to services, you might want to skip this post! (Crossposted from my From the Rabbi blog.)

This week's parsha, T'rumah, begins with God telling Moshe to tell the children of Israel to bring gifts. Moshe is to accept gifts from "each person whose heart is so moved." The gifts -- leather and wood, fabric and gold -- will be used to build the mishkan, the portable tabernacle: the house for God's presence.

The word mishkan comes from the same root as the word Shekhinah, the immanent, indwelling divine Presence. Shekhinah is the aspect of God which dwells here in creation; which dwells in us. And sure enough, in the verses we read today, God says, "let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them." Or, perhaps, "let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell in them."

We build the sanctuary out of our freewill offerings, the gifts of our own hearts. And in return, God dwells not in the physical structure, no matter how beautiful it may be -- but in us.

So if God dwells in us, why do we need to build the sanctuary?

Maybe we build the sanctuary not because God needs it, but because we do. Because something in us is changed when we give freely. When we build something beautiful. When we set our hands and hearts to the task of creating a space for God.

I am often asked why our prayers are so filled with praise for God. Surely God doesn't "need" us to tell Him (or Her) how great God is; why, then, is our liturgy so filled with reminders of God's transcendence and greatness? My answer is that we say these words not because God needs them, but because we do. Because something in us is changed when we remind ourselves that there is something in the world greater than we are. That we owe thanks to something beyond ourselves.

This sanctuary in which we pray this morning is a truly beautiful place. I feel blessed every time I step into this building. Every place where people gather to pray is a spiritually beautiful space, but this is a physically beautiful space, too. We have built a glorious mishkan here: not out of dolphin skin and acacia wood and hammered gold, but out of timbers and concrete and glass.

But what makes this a sanctuary is not the beauty of the building. It's not the elegant ark or the presence of the Torah scrolls. It's not even the ner tamid, the eternal light which burns above us. What makes this a sanctuary is the presence of our hearts. When we come together here, we make this into a sanctuary. And in return, we are able to be reminded that God dwells within us. Here, in our very hearts.

Shabbat shalom.

Here's the Torah poem for this week which appears in 70 faces:

THE GIFTS (T'RUMAH)

These are the gifts

leather and linen

silver and gold

each who was moved

returned these riches

to the place

every yearning heart

following the blueprint

these are the gifts

parchment scraped fine

and iron gall ink

commentaries in the margins

words intertwined

so that the tabernacle

becomes one whole

these are the gifts

that make the sanctuary

the presence dwells in us

February 23, 2012

Thoughts on Adar

Chodesh tov -- happy new month! Today is an extra-special new moon: we're entering the month of Adar.

"When Adar enters, joy increases." -- Ta'anit 29a (Talmud)

"The month which was transformed for them from sorrow to joy." -- Esther, 9:22

Adar is a month of joy for us because it contains Purim. Purim, when we celebrate the story of how the Jews of Shushan were saved from the plotting of the evil Haman, thanks to the righteousness of Mordechai and the bravery of his niece Esther. Purim, when we wear costumes and masks to disguise our usual selves (and perhaps in so doing, reveal some hidden facet of who we might be.)

On the surface, it seems obvious why Purim is a joyful holiday. We're celebrating yet another story in which our people survived against all odds! Purim features costumes, silliness, and commotion. At Purim, we stamp our feet and gnash noisemakers in synagogue to drown out the name of Haman. Purim plays (called Purimspiels) often feature ribald humor of the sort rarely otherwise heard from the bimah.

And, I think there are also other, maybe deeper, reasons why Purim is a time of joy. At Purim, we celebrate surprise twists and inversions. Haman plotted to destroy us, but instead he was destroyed; he erected a gallows for Mordechai, but swung on it himself. Purim reminds us that everything turns and changes, and that we can find holiness in the surprise twists and turns of our own story.

It appears at first glance as though the Purim story is entirely about good guys and bad guys -- but many Hasidic masters read this holiday as an opportunity to spiritually elevate ourselves beyond those distinctions. At Purim, we're instructed to become so "perfumed" by the celebration of the holiday that we entirely transcend the dualism of good and evil, moving to a place where all is God.

Speaking of God: at Purim, God appears to be entirely hidden. God's name is never mentioned in the megillah of Esther. (Those of you who've been reading this blog for some years have heard me say this before, but I think it is a gorgeous teaching every year, so forgive me, I'm offering it again.) It appears at first glance as though the story unfolds entirely without divine presence or divine help.

But many of the first several columns of handwritten text each begin with the same word: Ha-Melech, The King. The King, the King, the King. The Sovereign. The Ruler. Who is the real king in this story? Surely not Achashverosh, who comes across as something of a bumbling buffoon. The real king here is the one who is hidden, but is manifest everywhere for those who have eyes to discern: God. What greater reason could there be to awaken our communal sense of joy?

(Crossposted to my From the Rabbi blog, along with our Song for the Month of Adar.)

February 21, 2012

A really lovely review of 70 faces in the CCAR Journal: The Reform Jewish Quarterly

What a delightful surprise: The CCAR Journal: The Reform Jewish Quarterly (the magazine published by the Central Conference of American Rabbis) has reviewed 70 faces alongside three other collections of poetry (among them Merle Feld's and Yehoshua November's, both of which I reviewed for Zeek -- Feld's here, November's here.) The review, written by Rabbi Adam D. Fisher (the journal's poetry editor), can be found in the magazine's winter 2012 issue.

Here are some tastes of the review:

Rachel Barenblat, a rabbi living in Western Massachusetts, has given us a real gift -- a poem for each sidrah. They are beautifully written; accessible; and perfect for reading on a Shabbat afternoon or sharing with a community in a sermon, Torah, introduction to a Torah reading, or in a study group.There are so many good poems with so many important insights it is hard to know where to start...

I'm pleased that the editors of the journal opted to run a review of the collection, and honored that Rabbi Fisher likes the poems so well. Here's more:

Rabbi Barenblat writes a wonderful midrash on Sh'mini where it tells us to break any earthen vessel into which something unclean falls. In "Vessel," she writes, "The heart is an earthen vessel, / the body an urn." She then provides us with beautiful images of ourselves when she says that we are "made from dust . . . and patched with slip, / divine fingerprints everywhere." After pointing out a few of the unsettling things that happen to us she says, "each of these charges the heart / with uncanny energy, untouchable. / /All you can do is break the clay / wide open, crack the very housing. / What hurts is what draws you/ ever nearer to what we can't reach."

Barenblat also helps us with some of the most difficult-to-explain passages. In "Like God" (Tazria) she begins, "When a woman carries a grain of rice /invisible inside her rounded belly" then tells us some of the difficulties of pregnancy, and "when a woman gives birth to an infant / even the air around her crackles . . . /changed by the enorrnity of being like God/ and shaping new life in her compassionate womb." She gets us beyond the sacrifices and the ritual uncleanness, and gets to the heart of the matter: the wonder of pregnancy and childbirth. Barenblat, who has a son, doesn't romanticize pregnancy and childbirth but she does understand Tazria in terms of its most fundamental meaning.

Rabbi Fisher has kind things to say about the cycle of akedah poems, about the Jacob and Esau poems, the Moshe poems. He quite likes my poem for parashat Chukat: "She is especially inventive and playful in 'Red Heifer' (Chukat): 'Could Moshe have imagined / the Red Heifer Steakhouse / on King George Street/ in Jerusalem? He never crossed/ /the Jordan, a Diaspora Jew /to the last of his days...'"

And here's how his review ends:

Not every poem will strike a chord within all us -- no book could do that -- but there are such riches here that everyone will find many, many poems that will help him or her see these passages with new eyes.

Thank you so much, Rabbi Fisher! (As a reminder: 70 faces is available directly from the publisher, or on Amazon.)

February 20, 2012

Worth reading: two posts about Israel

I'm on the road and don't have time to write anything substantive this week, but I wanted to signal-boost a couple of things I've read in recent days.

The first is an essay by Israeli Dahlia Scheindlin: Dear liberal American Jews: Please don't betray Israel, published in the online journal +972. (If you're unfamiliar with the magazine, here's their About page.) Dahlia's essay calls on liberal American Jews to resist the temptation to turn away -- and also the temptation to remain silent.

I am particularly moved by her point that it seems, sometimes, as though American Jews love Israel only when we are shown its beautiful side. I think she's right that many of us who yearn for Israel to be the fulfillment of our highest ideals of righteousness have a difficult time facing some of what's happening there. But I suspect my Israeli friends would agree with her that we must resist the temptation to turn away. More: we must stand with our Israeli friends, relatives, and colleagues as they do the hard work of repairing their nation.

The other thought-provoking (though depressing) post I've read about Israel recently comes from Israeli-American Emily L. Hauser. Her post is called The Khader Adnan case and Israel's criminal stupidity, and it's about Palestinian Khader Adnan who is being held in "administrative detention" (which is to say: arrested without charge and held indefinitely) and who is near death from a longstanding hunger strike. (My colleague Rabbi Brant Rosen also posted about Adnan recently.)

Emily doesn't shy away from the reality that she doesn't like Adnan and she doesn't like Islamic Jihad, but she argues (and I agree with her) that administrative detention and torture are still unethical. She also makes the case that they are unwise -- that the Israeli government's treatment of Adnan only raises the profile of Islamic Jihad and creates another very high-profile martyr. (Rabbis for Human Rights has an excellent selection of Jewish teachings about torture and indefinite detention -- intended to spark conversation about U.S. policies, but the texts and teachings are equally valid here.)

I pray for peace and for transformation, in the Middle East and every place where violence and hatred mangle human lives. Please, God, speedily and soon.

Dear Velveteen Rabbi readers: please remember that I am traveling with my son and my online time is limited; I will not be constantly online to keep conversation civil. Comments are unmoderated for now, but please don't take that as an opportunity to speak unkindly toward or about anyone. Thanks, y'all.

February 17, 2012

Commentary on Mishpatim

My good friend Reb Jeff put up two posts recently about this week's Torah portion, Mishpatim. Here's a taste of one:

The rabbis loved the Torah so much that they struggled to find meaning in it, even in the places where it seems harsh or difficult.

We do the same thing with the people we love. When you love someone who has a difficult personality, you take extra pains to know that person more deeply, to understand the experiences that have shaped him or her so you can respond compassionately and with forgiveness, even when that person is being difficult. The Torah is like that, too. It was raised in an age when slavery was common, when men had tremendous power over women, and when most people had little control over their destiny. The Torah is shaped by those experiences. Because the rabbis loved the Torah, they probed it deeply to understand it and to read it compassionately as a text that brings deeper spirituality and meaning into life.

In our own day, we continue the process of interpreting the Torah. We don't need to reject Torah to deal with its difficulties. In fact, we embrace the idea that Torah should be difficult. It should challenge us to find meaning in our lives. Life, we know, is not easy and we need to learn how to negotiate life's challenges and hardships while maintaining our ability to find joy in it.

Read the whole thing here: Mishpatim: the Purpose of the Torah.

The other is a Torah poem, called simply Mishpatim. Here's a taste of that:

The legal jumble wants to be sorted

Like a box of samples and scraps.

What is cherished, what discarded,

What left-overs are sewn into my

Patchwork acceptance of the yoke?

Both are really worth reading. Thanks for your Torah teaching, dear Reb Jeff.

(And for those interested in Torah poetry, here's the poem I wrote out of this portion a few years ago: Like a feast. It also appears in 70 faces, though I think I revised it before publication there.)

Shabbat shalom from south Texas!

February 16, 2012

Texas-bound

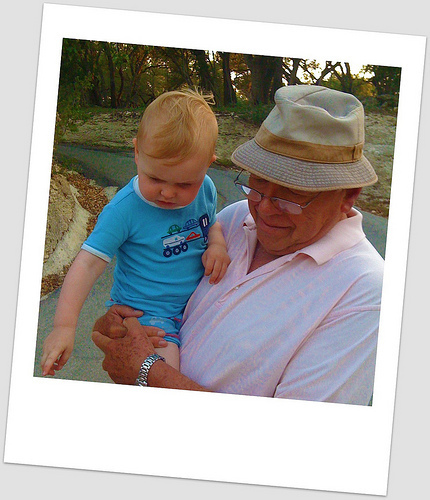

Last time we visited Texas, my son was 18 months old:

My son and my dad. June 2011.

This time, he's two years and 2.5 months. (Eight months make a big difference at this age.) I'm looking forward to once again reintroducing him to my hometown, and to his extended Texas clan.

I'm not sure he understands when I say we're going on a plane to see his grandparents, though he repeats the words: "onna plane! See Na, see Pop!"

And while we're there, we get to celebrate the wedding of one of my cousins. A joy all around.

Blogging will be minimal (or nonexistent) while we're on the road. So will my ability to respond to email and comments. Thanks for understanding. See y'all on the flipside.

February 13, 2012

Three scenes from congregational life

1.

On Shabbat morning I give a blessing to a nonagenarian in my kahal, who when I was in rabbinic school used to shake my hand after every service I led and tell me "good job." He has been a pillar of so many different communities and institutions around these parts (among them the local high school basketball team). He hasn't come to daven in a long time and there is joy in seeing him back in his usual sanctuary seat. I offer to bring the aliyah to him (our small sanctuary is intimate) but he wants to come up to the bimah. He slowly and painstakingly brings his tzitzit to touch the Torah scroll and recites the blessing with his daughters; then I read "Honor your father and your mother" and the room murmurs with appreciation at the confluence of life and verse. What an extraordinary blessing, to be able to do this, even though my voice is occasionally a bit scratchy all morning long.

2.

On Sunday morning I stand in for our usual Hebrew school storyteller and tell a fictionalized version of the story of Honi and the man who was planting a carob tree. Jane usually personalizes her stories, I've noticed. And having just read a version of the tale which is transplanted (as it were) into modern times, I decide to make the story about myself as a girl at a peach orchard in the Texas hill country. When we do our belated Tu BiShvat seder later in the morning and we reach the tale of Honi the kids make noises of recognition: they see what I did there. (I pause the seder to tell them the rest of the story -- about Honi sleeping for 70 years -- though I don't go as far as the ending, where he chooses death over solitude.) The dried figs are especially delicious, and the tiny cups of coconut water we drink in lieu of eating coconut. But my voice is only semi-present; I manage to lead them in a call-and-response rendition of Adamah v'shamayim but it's a near thing.

3.

Today a light snow has fallen. The new year of the trees may have come and gone, but the landscape is a white page marked only by animal tracks: winter has returned. Today I have no voice at all. An opportunity to imagine myself on a silent meditation retreat, I suppose, and to consider carefully everything I want to say before I type or write. Some of the things I do, as a rabbi, can be done in silence: emails following up on conversations, leaving little notes for congregants on Facebook, arranging this and that, planning future Hebrew school lessons for days when I have the voice to offer them. But most of what I do, I'm realizing, requires voice. My pastoral presence relies on my ability to respond to what's said. Even Torah study, our tradition teaches, is best done in hevruta, in the context of the friendship which arises through the back-and-forth of learning in conversation. What will I learn, I wonder, from the Torah of this experience, being temporarily unable to speak?

February 10, 2012

Caring for others, caring for ourselves - a d'var Torah for parashat Yitro

Here's the d'var Torah I'll be giving tomorrow morning at shul (so if you're going to be davening at CBI, you might opt to skip this post!) -- crossposted from my congregational From the Rabbi blog.

This week's Torah portion, Yitro, begins with a story about Moshe Rabbeinu -- our teacher Moses -- and his father-in-law Yitro, a Midianite priest. Moshe greets his father-in-law with a low bow and with kisses, both signs of great respect.

The next day, Moshe sits as a magistrate among the people all day long. By nightfall, Yitro counsels him: you can't do this alone -- the task of leadership is too heavy for you. Instead, Yitro advises him to establish a system of judges who can share the burden, and Moshe does exactly as his father-in-law suggests.

Immediately after that comes the passage we read in shul today, which tells how on the third new moon after the Israelites went forth from Mitzrayim, they enter the wilderness of Sinai. In that wilderness, they prepare themselves for revelation, and then God speaks the Ten Commandments -- tradition says, not only to those who were there that day, but to all of us throughout time.

But before the commandments, before that mystical Sinai moment, God says:

If you will obey Me faithfully and keep My covenant, you will be My treasured possession among all the peoples. Indeed, all the earth is Mine, but you shall be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. (Exodus 19:5-6)

וְעַתָּה, אִם-שָׁמוֹעַ תִּשְׁמְעוּ בְּקֹלִי, וּשְׁמַרְתֶּם, אֶת-בְּרִיתִי-וִהְיִיתֶם לִי סְגֻלָּה מִכָּל-הָעַמִּים, כִּי-לִי כָּל-הָאָרֶץ וְאַתֶּם תִּהְיוּ לִי מַמְלֶכֶת כֹּהֲנִים וְגוֹי קָדוֹשׁ

The earth and all its inhabitants are God's, but Torah says that we are something special. If we live in covenant with God, then we are God's סְגֻלָּה / segulah -- precious possession or treasure; we are מַמְלֶכֶת כֹּהֲנִים וְגוֹי קָדוֹ / mamlechet kohanim v'goy kadosh -- a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.

What can we make of this, and how does this relate to the story of Yitro with which the parsha began?

Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, the first Chief Rabbi of what would become the state of Israel, interprets these verses to mean that our community has two communal missions.

For Rav Kook, the phrase mamlechet kohanim (nation of priests) refers to the aspiration to uplift the entire world. It's our job, says Rav Kook, to act in a way which will help all the peoples of the world to fulfill their purpose and to live out their highest selves. Of course, in his paradigm, that meant: it's our job to teach the world God's ways. To ensure that everyone cares for the widow and the orphan, shows compassion to the stranger, acts justly and righteously as Torah describes.

But Torah also tells us that we're meant to be a goy kadosh, a holy nation. Rav Kook interprets this as the flipside of the coin: on the one hand we're meant to teach the whole world how to be righteous, and on the other hand we're meant to focus inwardly, to live out holiness in our own lives. Being a holy people means tending to our own spiritual growth.

Yitro is a Midianite priest, an outsider to the Israelite community. But when he shares his wisdom and his management insights with Moshe, Moshe takes them to heart. Given the Torah's generally negative stance toward the other nations of the Ancient Near East, I've always found it remarkable that Yitro is so obviously respected and trusted despite being a foreign priest. But this year, I see a connection between the Yitro story and this verse which asserts that we are God's treasure, a nation of priests, and holy.

Torah reminds us that all the earth is God's, but asserts that our community has a special role. In Rav Kook's interpretation, our community's task is both outward-facing and inward-facing. It's our job to help everyone in the world live up to their best and most righteous self, and it's also our job to care for our own souls.

As a "nation of priests," we're obligated to tend to the entire world. As a "holy nation," we're obligated to tend to our own selves. The Torah balances these two callings within the same verse. If we only tend to our own selves, we're falling down on the job of caring for all creation; but if we don't tend to our own selves, we can't heal the world.

This is, I think, part of what Yitro taught Moshe when he urged him to find righteous men who could serve as magistrates. If Moshe tried to adjudicate every single disagreement and dispute in the entire community, he would burn out! But once he'd appointed judges, he was able to tend to his own spiritual needs, which in turn allowed him to continue tending to the community.

Yitro is an outsider, not part of our covenant with God, and yet he still clearly has spiritual wisdom. Not only that: it's spiritual wisdom which Moshe really needs. We, too, may find valuable spiritual wisdom outside of our own gates. Our task is to integrate that wisdom-from-outside with our spiritual tradition and our spiritual path, so that we can truly be a mamlechet kohanim and a goy kadosh.

What does it mean to you to imagine us as a nation of priests? If a priest's job, in those days, was to connect the people with God, how can we live out that responsibility now?

What does it mean to you to imagine us as a holy nation? Not "the" holy nation, not the only holy nation, but a community which is collectively holy. If, as Rav Kook says, this means that we are a nation which tends to its own spiritual sustenance, then how might we live that out in our own day?

February 9, 2012

How to have a Wednesday

Wake up before the alarm.

Linger in bed for five more minutes.

Shower. Recite Modah Ani in the shower. Dress.

Listen for the toddler: not making any noise.

Good, a few minutes to check email. Check email. Respond.

Close up laptop, go downstairs, enter the toddler's room.

Watch him sleep, a comma curled at one end of his crib, breathing slow and steady.

Feel tenderness. Feel regret at having to turn off the white-noise machine.

Listen to his breathing change and his babble begin.

Chat with him. Change his diaper.

Pull a green shirt with a moose on it out of the drawer.

When he refuses it, put it back and look for a blue shirt, per his request.

Feel relief that he accepts a shirt with blue stripes.

Give him goldfish. Play with trains.

Pile him in the car, go to daycare, drop him off.

Drive north to the coffee shop.

Get a cup of joe and a bagel with chive cheese.

Read email again. Respond.

Meet with colleagues. Talk about life. Study some Torah.

Talk about possible themes for Shavuot. Inside / outside. Otherness. Harvest.

Meet with the youth group leader to plan a trip to the big city.

Feel chagrin about not having time to dedicate to the youth group.

Remind yourself again that this is a half-time job.

Answer more email. Tell a friend you love him.

Dash to the high school. Find the principal's office.

Meet there with two principals and another rabbi to talk about diversity.

Discuss the invisible backpack of privilege, Anne Frank, living color.

Emerge into the sunshine. Head to the grocery store.

Choose fruits with shells, fruits with pits, fruits which are soft all the way through.

Nab a plate from the salad bar because no way is there time for lunch.

Stop at the liquor store, pick out some wine with pictures of trees on the label.

Chat with the salesman about the bourbon made just down the road.

Race to synagogue. Unload the groceries. Eat lunch at the desk.

Cringe to notice your lousy posture (again) and your kinked-up back (again.)

Choose green tablecloths for the seder table.

Pick up fallen branches from the woods behind the building, for a centerpiece.

Trim the centerpiece because otherwise it's going to poke people in the eyes.

Answer email. Schedule a puppet-making workshop.

Research blessings for aging. Dig up Reb Zalman's Elder Creed.

Realize you don't have a text for Torah study this week.

Browse a few different books before deciding to check out Kedushat Levi.

Translate a short text. Ponder the translation. Revise for clarity.

Dig up a citation and read that. Format a handout. Answer email.

Take a phone call, offer condolences, feel sorrow.

Take another phone call, say yes of course there's always room at the table,

run out to move the tables and add more chairs.

Make five more copies of the haggadah for Tu BiShvat, collate, staple.

Send an email about a shiva minyan.

Make a handout for Shabbat morning.

Tidy the sanctuary. Drag the classroom table out, set the chairs back in semicircles.

Practice guitar chords. Finish setting the Tu BiShvat table.

Take a phone call from a woman in dire straits a thousand miles away.

Offer her a blessing for her luck to turn, promise to do what you can.

Wish you had any idea how to verify her story. Wish you had money to send.

Rub your eyes, which feel gritty and leaden.

Put on your coat, go outside, daven mincha.

Marvel that at 5pm it is not dark. Know that spring is coming.

Change gears. Welcome people into the building.

Celebrate Tu BiShvat with a potluck seder.

Know that the sap is rising: in the maples, in the cosmic tree of life.

Know that we can eat in a way which creates healing on high.

Wonder whether you've communicated these things with anyone.

Talk about foreign languages; attempt to answer a Harry Potter riddle.

Drive home, too late to see the toddler.

Thank your in-laws for looking after him.

Have a glass of wine.

Sleep.

February 8, 2012

Etrogcello for Tu BiShvat

Remember last Sukkot? The sound of cornstalks rustling on the roof of my car as I drove slowly home from Renton's farmer's market. The trees on our hills still bright with fading leaves. Carrying my lulav and etrog out to the sukkah in the rain-washed morning, and shaking them in all four directions as I dodged the raindrops still dripping from the sukkah's so-called roof.

And then, when the festival was over, my reluctance to discard the beautiful fragrant etrogim. They had come such a long way to reach us, just in time for the festival! So I peeled them, and poured vodka over the thin shavings of yellow skin, and set them in a cupboard to wait in the dark. At first the shavings sat at the bottom of a bottle of clear liquid. Over time, some alchemy transpired. The liquid became golden, the peel ever-more translucent. Now, some months later, they have been transformed from this:

Etrog, sliced open.

To this:

Before decanting.

I open the jar and am washed with a heady wave of the scent of etrog. Surely smell is one of the most evocative senses: one whiff and I'm transported back to the day before Yom Kippur when I first lifted last year's etrogim out of their foam cradles and brought them to my face to inhale their extraordinary scent. Nothing else smells quite like an etrog. It's lemony, yes, to be sure, but it's more than that. Richer, sharper, more complicated. Over the years I've experimented with etrog preserves, but no jam ever quite captures the way an etrog smells -- the way it makes me feel -- when I first press it to my nose before the festival begins.

But this etrogcello comes close.

A few weeks ago I made a Splenda simple syrup and added it to the jar, then returned it to the darkness. Yesterday, Tu BiShvat almost upon us, I washed out two plastic bottles and prepared them for their new contents.

The 2012 vintage.

We actually still have a couple of tiny flagons of last year's etrogcello left over. It's not as bright or as pungent as this year's stuff, though it's still tasty. I brought some to our Simchat Torah celebration last fall -- after we danced the Torah scrolls around the Williams College Jewish Center, when the traditional schnapps and vodka were brought out for toasting, I added a wee bottle of etrogcello to the table. It was a surprise, a special treat -- a little taste of Sukkot although Sukkot had just ended.

But really the reason I make the etrogcello is so that we can drink it at Tu BiShvat. The New Year of the Trees; the birthday, according to Talmud, of every tree, no matter when it was planted. The date when (our tradition says) the sap begins to rise to feed the trees for the year to come; the time when cosmic sap begins to rise, renewing our spiritual energy for the welter of spring festivals ahead. How better to celebrate Tu BiShvat than with this pri etz hadar, this fruit of a goodly tree, which we so cherished back at Sukkot? It stitches the harvest season to this moment in deepest New England winter. It reminds me that everything which has been dormant can once again bear fruit.

Tonight at our seder I will raise a glass: to the memory of last Sukkot, to the anticipation of next Sukkot, to the trees which bore this etrog, to the many hands which brought it here, to the Source of All from whom all blessings flow. L'chaim!

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers