Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 233

January 14, 2012

Names, and opening our eyes

Here's the d'var Torah I gave this morning at Congregation Beth Israel. (Originally posted at the From the Rabbi blog.)

In this week's Torah portion we re-enter one of my favorite stories, and one of the deepest stories, about Moshe Rabbenu, our teacher Moses. It is also, I believe, a story about each of us.

Moshe is tending sheep in the wilderness when something remarkable happens. An angel of God appears to Moshe in the midst of a burning bush.

According to the late 13th century Kabbalist Bachya ben Asher, there's a process here of opening of awareness. Moses first sees a bush, then he sees that it's on fire, then he sees that it's not consumed. He's really looking at what's there -- not just filling in the blanks of what he expects to see, which is the way most of us see things most of the time. Moshe, though: he looks deeper into the bush which burns, and then he's able to hear the voice of God.

Take off your shoes, God tells Moshe -- the Torah tells us -- for you stand on holy ground. In the Hasidic understanding, this isn't a literal instruction about footwear so much as an instruction about removing whatever impediments are keeping us from encountering holiness. Remove your habitual ways of seeing so that you can witness the miracle before your eyes. Remove whatever is keeping you distant from God.

This is going to sound like a digression, but I promise you it isn't. Every morning, in the blessings for the miracles of each day, we say the blessing Baruch atah adonai, eloheinu melech ha'olam, poke'ach ivrim -- Blessed are You, Adonai, who opens the eyes of the blind. And then later, we say Baruch atah adonai, eloheinu melech ha'olam, ha-mevir shena m'einai u'tnumah me-afapai -- who removes sleep from my eyes and slumber from my eyelids.

Why, the sages ask, do we bless God Who opens our eyes and only afterward bless God Who removes sleep from our eyes and slumber from our eyelids? Shouldn't it be the other way around? And our sages answer: it's because falling asleep can always happen. And waking, too. The film that covers our eyes -- sometimes we're not even aware that it's there. This isn't, in other words, about literal sleep or literal blindness.

Moshe looks at the burning bush and he sees that it's a miracle because his eyes are truly open. We, too, stand in front of the burning bush. It still burns. It's up to us to practice opening our eyes, on every level, so that we can see all of the miracles which are right in front of us. So often, we go through our days spiritually asleep: our eyes may be open, but we're so caught up in our anxieties or frustrations or distractions that we don't notice God's fire right in front of us.

At the bush, Moshe says: You're giving me a mission, but who shall I say sent me? And God says, tell them that you were sent by the God of your ancestors; tell them that Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh sent you.

Many of you know that the Tetragrammaton, the Name of God which we can spell but not pronounce -- Yud / Heh / Vav / Heh -- is often understood as a mysterious form of the Hebrew verb "to be." It seems to mean something like Was and Is and Will Be, all at the same time. And sure enough, God's name here is given as Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh, I Am Becoming What I Am Becoming. God says, tell them that I Who Am Becoming sent you.

We are made in the divine image. Like God, we are always becoming. And we don't know who we will become. In Stanley Kunitz's words, in his beautiful poem The Layers:

Though I lack the art

to decipher it,

no doubt the next chapter

in my book of transformations

is already written.

I am not done with my changes.

The fact that we are always changing is part of what makes us like God. God isn't static, unchanging, always the same. On the contrary -- God is constant transformation. God is the force for transformation in our lives.

An invitation. To notice the miracles around us. To notice the bush as it still burns on. To remove whatever stands in the way of our encounter with God. To remember that, like God, we are always becoming -- and like Moshe, we are always confronted with radical new possibilities, if only we will open our eyes.

January 13, 2012

My second smicha

Getting my wings. Photo by Janice Rubin.

At the Ohalah conference this year I was ordained a second time, as a Mashpi'ah Ruchanit -- a Jewish Spiritual Director. This journey began three years ago, with the first winter intensive retreat of this second hashpa'ah training cohort; I wrote about that in the post Our first four days of hashpa'ah.

What is hashpa'ah? The Hebrew term comes from the root which connotes shefa, divine flow; a mashpia (M) or mashpi'ah (F) strives to help people discern the presence of God in their lives. (The most common English term for this work is spiritual direction.) For me, hashpa'ah is first and foremost a relationship. In my practice of hashpa'ah, I hope to help others navigate Jewish faith and practice in a way which encourages and fosters deeper relationship with the Divine -- as my own mashpi'ah does for me.

ALEPH's spiritual direction training program is unique; as far as I know it's the only one of its kind (leading both to certification and to smicha, ordination). It includes four intensive classes (learning done in-person on retreat), three semesters of teleconference coursework, four semesters of supervised hashpa'ah practice with individuals and groups, and supplemental learning in related areas. Participants trained individually and in group settings with mashpi'im (spiritual directors) who supported our spiritual growth in relationship to God and sacred service, and who modeled different forms of spiritual counseling and spiritual direction for and with us.

Reb Zalman addresses the hashpa'ah musmachim. Photo by Janice Rubin.

The training culminated in a beautiful ceremony. Two by two we approached the bimah and placed items of personal meaning on the bedecked table which served as our makeshift altar. There was some chant, some learning (I especially enjoyed Reb Zalman's short history of hashpa'ah, from his experiences in Chabad in 1942 all the way through the foundation of this ordination program), and some presentations by the musmachim which aimed to offer glimpses of our training and our work.

And then we were each called up by name. Each of us stood with our teachers on all four sides: Reb Nadya behind us, Reb Shohama in front of us, Reb Sarah and Reb Shawn to left and right. One by one each of us was ordained to serve as mashpi'a(h) ruchani(t) and blessed to go forward from the place where our teachers stand. And then we left the bimah, collected our items from the makeshift altar, and processed down the aisle through the gateway of our teachers' arched hands...

...to receive, with great laughter, pairs of beautiful bright red feathered wings. Because we learned a lot during these three years about angels in Jewish tradition, and this hashpa'ah smicha is sometimes jokingly referred-to in our community as "getting your wings." And while while we take the work of spiritual direction seriously, and we take the calling of helping others connect with the presence of God seriously, we tend not to take ourselves too seriously. The beautiful certificate of ordination, I'll frame and place in my rabbinic office; the wings, I suspect, may stay in my home office, mementos of a sweet moment at Ohalah 5772.

January 11, 2012

Dear ALEPH and Ohalah hevre

Y'all are awesome.

Okay, I don't actually know all of you. Even after six Ohalah conferences, I don't quite know everyone in Ohalah, and it's a little bit surreal to discover that I don't know all of the ALEPH ordination students anymore, either. But many of you are among the people most dear to me, and many others among you are the kind of once-a-year-friends with whom I am always happy to daven, to eat, to sing, to exchange a beatific smile across the sanctuary or across the buffet line.

Some of you are people I met at my very first retreats at the old Elat Chayyim in Accord, New York, back when I was first discovering Jewish Renewal and learning that the Reb Zalman about whom I had read in The Jew in the Lotus really was as wonderful as he sounded. Some of you are people I met during my first smicha students' week, when I was in the process of applying to the ALEPH rabbinic program -- I remember raising a cup of ginger tea with some of you in the old Elat Chayyim dining room, toasting to "smicha or bust!" Some of you I have known since college; some of you I have only just met.

Some of you are teachers who have enriched my life with the wonder of Torah's endless riches. Some of you are my friends who have also become my teachers. Some of you are my teachers who have also, much to my delight, become my friends. Some of you laid your hands on me this time last year and ordained me to serve as a rabbi, which remains one of the most powerful experiences of my life. Some of you laid your hands on me this year and ordained me as a spiritual director, which was gentle and sweet.

During these five days of Shabbaton and conference we've davened, sung, studied, and chatted together. We've opened our minds and hearts to new ideas and new insights. We've luxuriated together in the hot tub under the stars. We've argued and discussed, learned and leyned. We know that these are things which have no limit, and that we are blessed to be able to do them together.

I love the fact that every year at this season I get to join you here in Colorado, to beam at you and embrace you, to catch up on your lives and to share news of mine, to show off photos of our children and our pets on our phones. I love the fact that when we daven together I get to sing favorite old melodies and also to learn new ones. I love how we break into impromptu harmony together, day after day. I love how every time we gather, the time since our last gathering seems to collapse in a kind of tesseract and it's as though we never parted.

Thanks for a wonderful Shabbaton and conference. I'm heading home happily exhausted, my brain filled with ideas and melodies, my heart filled with our connections. Cosi revaya: my cup overflows. May your travels home be safe and smooth, and may the Holy One of Blessing watch over you until we meet again.

January 10, 2012

Rumi illuminating morning prayer

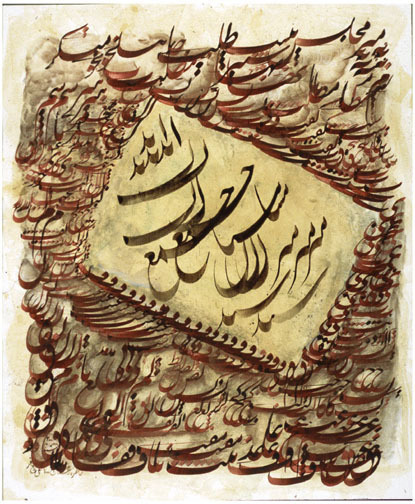

Sufi calligraphy; image borrowed from Rumi Online.

You could be forgiven for imagining that all my rabbinic community does, when we get together, is pray. It's not true, of course. The Ohalah conference includes all sorts of plenary sessions and workshops. Also we schmooze, study together, break bread together, laugh and cry together. (Just within the first 24 hours of this year's conference, I got to study the halakhot of menschlichkeit with Reb Sami, to attend a tikkun olam committee meeting, and to pore happily over Rosensweig and Levinas with Reb Laura.) But the prayer is often a particular treat for me. I have other opportunities in my life for schmoozing and studying, but not always for encountering creative approaches to prayer.

Yesterday morning I attended a really beautiful service led by my friend Rabbi Ed Stafman -- a service in which each of the prayers of the morning liturgy was paired with a poem by Persian mystic poet Rumi. It was amazing. Reb Ed chose the Rumi poems so that each would illuminate a particular prayer or line of prayer. Some of the poems he chose were old favorites of mine; others were new to me. Many of them took my breath away, both as poems qua poems and as ways of expressing the ideas and themes I find in our liturgy.

I love the way that these poems offer me new understandings of the liturgy I know so well. And they're beautiful poems, too; they're excellent on their own. But used in this way, as lenses through which to read the traditional prayers, they open the liturgy for me in new ways.

Here's one of my favorites from that service. This is the Rumi poem which R' Ed paired with the blessing for peace which comes at the end of the amidah. (The translation is by Coleman Barks.)

One Song

Every war and every conflict

between human beings has happened

because of some disagreement about names.

It is such an unnecessary foolishness,

because just beyond the arguing

there is a long table of companionship

set and waiting for us to sit down.

What is praised is one, so the praise is one too,

many jugs being poured into a huge basin.

All religions, all this singing, one song.

The differences are just illusion and vanity.

Sunlight looks a little different

on this wall than it does on that wall

and a lot different on this other one,

but it is still the same light.

We have borrowed these clothes,

these time-and-space personalities,

from a light, and when we praise,

we are pouring them back in.

I love this poem, especially the idea that "what is praised is one, so the praise is one too, / many jugs being poured into a huge basin." And I also love it as a mirror for the Sim Shalom blessing, which asks God to grant peace (and also goodness, blessing, grace, lovingkindness, and compassion) to us and to our community and our people.

This is exactly the kind of thing which draws me back to Ohalah each year: not only the chance to pray and learn and laugh and sing and dine with dear friends, but also the chance to be enlivened by new ideas which I never would have imagined had I not come. I'm already planning a Rumi-based service for the congregation I serve. (It will be on May 5; if you're in or near Western Massachusetts, do join us.)

January 9, 2012

Amazing Shabbat morning prayer

There's really nothing like the experience of praying with a room full of people who I know and love (and who know and love me), all of whom know and love the liturgy, all of whom offer prayers with song and joy. This is one of the things which is most revitalizing to me about spending time with my ALEPH community.

Shabbat morning services at the pre-Ohalah Shabbaton this year were amazing. Everyone on the bimah was a dear friend of mine, which meant I felt an outpouring of warmth (in both directions: from me to them, from them to me) the moment I walked in the room. Two of my friends led an extraordinary psukei d'zimrah (the opening section of the service -- psalms and poems of praise), which featured chant and song and the tiniest tastes of silence to help the prayers reverberate within us.

I knew we were in good hands from moment one, so I was able to relax into the prayer experience right away. The music was so good -- and the prayers so heartfelt and fervent -- that I was honestly transported. After the first psalm or two, David leaned over to me and whispered "welcome home." And yeah: that's very much how this feels. Returning to a kind of portable home, constructed every time we gather, made from prayer and from song. And there was nothing else tugging at us, nothing else we were supposed to be doing or remembering or thinking about. It felt as though our only purpose, that morning, was to come together and sing praises. Which is what Shabbat is supposed to be, though it isn't always.

Singing the Iraqi setting for "Hallelu Avdei Adonai" (which you can hear recorded by Richard Kaplan and Michael Zielger if you're so inclined) was particularly sweet for me. There was good hand-drumming, and the community picked up the refrain easily and sang it with fervor. As the melody skated higher and higher I found myself teary with joy. "Offer praises, you servants of the Most High" -- it's amazing to pray those words when everyone in the room understands themselves to be such a servant. Rabbis, rabbinic pastors, cantors, spiritual directors: we've all dedicated ourselves to serving God and serving our community. We sang our hearts out. It was grand.

I could have been content to stop there, with just p'sukei d'zimrah and shacharit (the first two parts of the service) -- but of course there was more! And the Torah service was fantastic too. Another of my friends led us through that service, singing the words and melodies of bringing forth Torah in a way which made clear how much those words meant to her and to all of us. And still another of my friends gave the dvar Torah -- and in so doing, brought the room to a kind of charged anticipatory silence, as one might experience at a really good poetry reading or a really powerful wedding. We hung on his words and they opened up Torah for us in new ways.

From the very first wordless niggun at the start of the morning, to the closing Adon Olam at the end of the morning, we were awash in harmony and praise. It was pretty awesome, in the original sense of that word. I am so grateful.

January 8, 2012

Mountain streams

How lucky I am that these are two glimpses of my first week of January:

A stream running at the foot of Shaker Mountain, which I climbed last Wednesday

with dear friends on a geocaching excursion. (The mountain, I mean, not the stream.)

A stream at the trailhead of a trail somewhere in Boulder County

where I strolled on Friday with other dear friends before the beginning of the Ohalah Shabbaton.

January 5, 2012

Ohalah-bound

I can measure the last six years in Ohalot (Ohalah being the name both of the association of clergy for Jewish renewal, and the annual conference which that organization puts on.)

2006: I was a new ALEPH rabbinic student, over the moon at being able to name myself so. 2007: I had recovered enough from my strokes to be cleared to fly, but I had no idea what health mysteries might have caused the trauma. (Still don't.) 2008: getting swept up in the whirl of davening Hallel with my teachers and friends. 2009: I miscarried on Shabbat, and my friends cared for me. 2010: the year I stayed home with our newborn son, imagining my beloved friends and teachers far away. 2011: the year I became a rabbi.

And here comes Ohalah 2012. Tomorrow morning, at a painfully early hour, I'll be off to Colorado for the Shabbaton and ensuing Ohalah conference yet again, for the first time as a rabbi. On Saturday night I'll be ordained a second time, as a mashpi'ah ruchanit, a Jewish spiritual director. On Sunday I'll have the joy of seeing several of my friends ordained.

I wonder how it will feel to return to the OMNI hotel outside of Denver, which was new to us last year when we converged there for my ordination. I dimly remember last year's arrival, with a dozing baby in the car seat and my spouse and parents in tow. I remember strolling Drew through the empty hotel lobby at 3am, trying to coax him back to sleep again. This year, Drew will stay home with his dad, enjoying all the comforts of home -- his dear daycare provider, his comfy crib, his house full of toys -- and I will spend five days with my hevre, reconnecting with colleagues and teachers and with God, adrift in the freedom of being temporarily childfree.

And of course there will be experiences I can't quite anticipate. Melodies and harmonies. Meals with beloved friends. Prayer both scheduled and spontaneous. Conference sessions which open me up in surprising ways. These things are always true.

To those among y'all who I'll be seeing in Colorado: travel safely and I can't wait to reconnect! And to those who won't be there, have a lovely few days.

January 3, 2012

Preparing for 10 Tevet

This post may be triggering for survivors of rape and sexual abuse. If that is you, please guard your boundaries carefully, and feel free to skip this one if you need to.

For many liberal Jews, fasting means the experience of forgoing food and drink on Yom Kippur. Others also observe the custom of fasting on Tisha b'Av, the day which commemorates the fall of both Temples in Jerusalem. These two days are Judaism's major fasts. But there are also five minor fast days on the Jewish calendar. Minor fasts last from dawn until nightfall, and (in the traditional understanding) one is permitted to eat breakfast if one arises before dawn for the purpose of doing so, though one must finish eating before first light.

Of the five minor fasts, one is the "fast of the first-born," observed by first-born males on the day preceding Pesach, in commemoration of the story of the tenth plague and how the Hebrew boys were spared. The other four minor fasts relate to historical happenings, tragedies which still resonate in Jewish memory. One of these falls this week: 10 Tevet (on the Gregorian calendar, this year that's Thursday, January 5), which commemorates the beginning of the siege of Jerusalem by the armies of Nebuchadnezzar, a siege which culminated in the fall of the first temple in 587 BCE.

What does it mean to fast in memory of the beginning of a siege 2,601 years ago which led to the fall of a temple some thirty months later -- especially when for many of us, the sacrifices which went on in that temple feel so foreign we can't begin to relate to what they meant? And what might Asara b'Tevet mean to someone who eschews the fast itself, or someone who is perhaps only now learning that this minor fast day exists?

We remember the siege of Jerusalem because it was the beginning of the process which led to our exile from that city and from the place where we knew how to connect with God. And though it can be argued that the exile ultimately led to the flowerings of rabbinic Judaism, of a Judaism which is rooted in the portable connections with God which we create and sustain through study and prayer everywhere we go, the exile was still a trauma. I think there's value in recognizing that.

The essay Walls and Gates (on Chabad.com) reminds us that "[a] broken wall means vulnerability, exposure, loss of identity." 10 Tevet is a day for recognizing, and mourning, siege which leads to brokenness and damage. For some, that means remembering the siege of Jerusalem long ago and mourning the shattering of that city's integrity. (For others, it might mean mourning the shattering of integrity indicated by Haredi violence in the Jerusalem suburb of Bet Shemesh in recent days.)

For still others, the commemoration of siege which led to brokenness may suggest another, more intensely personal, form of shattering. If your bodily integrity has been compromised, through rape or other sexual abuse, the 10th of Tevet may offer an opportunity for recognizing and mourning the breach in your safety and your wholeness. This profound trauma exists in every community. For me, there is something powerful about also understanding 10 Tevet as a day of remembering, and mourning, this breach of trust and of wholeness which so many suffer -- not instead of the traditional interpretation, but in addition to it.

Fast days are traditionally considered to be days of teshuvah (repentance/return), turning ourselves so that we are oriented toward holiness and toward God. Whether or not your practice includes fasting on the 10th of Tevet, I invite you to spend this Thursday engaged in teshuvah. And I invite you to spend this Thursday -- the 10th day of the lunar month of Tevet -- in mindfulness. Sit with what hurts: whether that's the memory of the siege of Jerusalem 2600 years ago, or the memory of your own experience of being besieged and broken-into, or the uncomfortable awareness that we allow the suffering of rape victims in our communities to remain invisible. Make a conscious effort to open your heart to this suffering.

May our observance of 10 Tevet, whatever form it may take, align us more wholly with compassion and kindness, and may those who have been besieged find safety and healing, speedily and soon.

January 1, 2012

A blessing for the new year, from Reverend Howard Thurman

My teacher Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi tells a story about how, when he began studying religion at Boston University, he used to enter the chapel each morning to pray. Shortly after he began this practice, he noticed that someone had moved the crucifix aside and placed the Bible in the center of the room -- in apparent deference to his needs. In entering the chapel a bit early one morning, he saw who was moving the cross -- an African-American man who he thought might be the janitor.

Still, he questioned whether academic study of religion was "kosher" for him, and one day he went to visit the dean -- one Reverend Howard Thurman, the very same man -- he realized -- who had moved the cross to make Reb Zalman more comfortable. Reb Zalman admitted his fears about the academic enterprise at hand: would it shake his faith? Would it cause him to doubt? "Don't you trust the ruach ha-kodesh?" asked Reverend Thurman -- and Reb Zalman realized that he did, and that if God had led him there, surely it was where he was meant to be.

In my commonplace book I recently rediscovered this quotation which I had copied from somewhere. (The quote's source is Meditations of the Heart, though I do not own the book, so I'm not sure where I found it!) I thought it would be a fine way to begin the secular new year here at Velveteen Rabbi.

Reverend Howard Thurman: "Through the Coming Year"

Grant that I may pass through

the coming year with a faithful heart.

There will be much to test me and

make weak my strength before the year ends.

In my confusion I shall often say the word that is not true and do the thing of which I am ashamed.

There will be errors in the mind

and great inaccuracies of judgment...

In seeking the light,

I shall again and again find myself

walking in the darkness.

I shall mistake my light for Your light

and I shall drink from the responsibility of the choice I make.

Nevertheless, grant that I may pass through the coming year with a faithful heart.

May I never give the approval of my heart to error, to falseness, to vanity, to sin.

Though my days be marked

with failures, stumblings, fallings,

let my spirit be free

so that You may take it

and redeem my moments

in all the ways my needs reveal.

Give me the quiet assurance

of Your Love and Presence.

Grant that I may pass through

the coming year with a faithful heart.

Amen!

December 29, 2011

Top ten (prose) posts of 2011

Every year I post a round-up of my ten favorite prose posts -- here's the 2010 edition. (Some years I also post a list of my ten favorite poetry posts, though I'm not sure I'm going to manage that this year.) It's always fun, as the calendar year winds down, to look back over what I've written and where this blog has taken me.

Perhaps not surprisingly, none of my posts about politics or current events (either in the US or in the Middle East) made the cut. It's interesting; whenever something major is unfolding I feel the burning need to comment on it, but as months or years go by, those posts don't stick in my mind, and upon rereading they often feel mired in their original moment. Or maybe I'm just more inclined to see my more spiritual work as timeless. Who knows.

Anyway: with no further ado, here are my ten favorites posts from 2011! Here's to 2012.

Three scenes from the day of my smicha. And then the ten of us sit in a circle facing outwards, with another ring of chairs facing us, and one by one, our teachers take turns sitting in the chairs which face us and they give us blessings. My teachers bless me with savlanut (patience), with the ability to balance the rabbinate and motherhood, with the awareness that it's always okay to put my family first. My teachers bless my ability to write, and also bless me that I might be aware that sometimes the writing is a safety net because words come so easily to me. They say extraordinary things about who they understand me to be and who they understand me to be becoming. I am blown away. Again and again my cup overflows. One teacher blesses me with words about the smicha of Moshe and the rabbis of the great assembly, placing hands on my shoulders, and I weep.

This is spiritual life. There's no necessary dichotomy between real life and spiritual life. Spiritual life isn't just something that happens when we can make time for it, or when we can dedicate ourselves to it wholly -- as delicious as that is! Those of us who've had the luxury of occasionally going on retreat know that the real challenge can be integrating the peak experience of the retreat into ordinary life once one has come home again. The question isn't "who am I when I can spend my morning in yoga and meditation and prayer" -- it's "who am I when I wake up to the baby and the bills and the tasks on my plate?"

Tasks which have no limit. A funeral needs to happen when it needs to happen, regardless of whether or not it's "convenient" -- just as a child needs to eat, or nap, or be held, or be entertained at the moment when the child needs those things. (Older children's needs can, I know, be shifted somewhat...but that largely hasn't been my experience of parenthood yet.) Funerals can be painful, messy, inconvenient just as children can. It can be difficult, I am learning, for a rabbi-mama to simultaneously navigate the needs of mourners and the needs of a child.

A Passover letter to my son. Will you grow up in love with liturgy, as I did? I have no idea. You will become whoever you become. I do hope that you will come to cherish this holiday, this season when we retell the story of how our people came to be a people, how we were lifted out of slavery and constriction by God's mighty hand and outstretched arm. How it is possible that even though this is a once-upon-a-time story, it happened to each of us -- it happens to each of us even now. I hope you'll thrill to the songs and the flavors as each year's new spring unfolds. I hope you'll ponder the question of what it means to be free.

A sermon in poetry for parashat B'ha-alot'kha. This week's Torah portion, B'ha-alot'kha, begins with the instruction to kindle seven lamps in the portable Tabernacle. The Torah is filled with detailed instructions for the construction of the mishkan, the place where God's presence dwelled among us. Of course, even if the mishkan's construction is a historical reality rather than a spiritual and literary one, centuries have passed since it was built. What can this verse about a golden lampstand tell us about our spiritual lives today? When I look at the verse through the prism of poetry, I find metaphors which hold meaning.

Seeking and finding (six more glimpses of Kallah). A glorious morning service out on the big quad. The air is cool at this hour and I relish my tallit wrapped around my shoulders. The davenen is led by two of my ALEPH chevre, both cantorial students, and the singing is wonderful: just the right balance between beloved melodies and classical nusach. I realize, at the end of the service, that I ought to have recorded it so I could sing along with it when I daven at home -- but I didn't think of that in time; it can only be what it was, a beautiful hour of prayer which arose and then disappeared like a sand mandala after a wind.

This year's wrestle with Tisha b'Av. During most of the year, I explicitly reject the victim mentality which looks at history through the lens of all of the awful things which have happened to us... but I've come to think that there may be value, once a year, in sitting with our painful history. Maybe if we go deep into these narratives today, we can free ourselves from the need to carry them with us every day as we live in the world. Maybe we need a day when we remember our collective traumas, from the Babylonians to the Romans to the Crusades, so that having immersed in those stories we can make the conscious choice to shape our narratives and to understand our place in the world differently.

Earth and pine. The fresh scents of newly-turned earth and sweet unfinished pine might connote a construction site, a place where new dreams are being built. I think of the ground opening up to hold a new structure, scaffolding rising into the waiting sky. But these are equally the scent of a Jewish funeral in summertime, when the earth is warm enough to be fragrant as it is opened to receive. The plain pine box in which Jews are traditionally buried has a woodsy scent which rises on the summer air, and the earth smells like new furrows, like farmland, like something precious enough to cradle in our own bare hands.

On compassion (inspired by Dr. Dan Gottlieb). Gottlieb's essay inspires me. Faced with physical trauma I can't begin to imagine, he finds his way to a place of feeling blessed by love and relating to his own body with compassion. This is the kind of profound existential shift which I hope that my prayer life (including my meditation practice) can help me achieve. This is, I think, a kind of teshuvah, a turning or re-turning to orient oneself in the direction of holiness and connection with God. When I can relate to my body, mind, and spirit with compassion, I am more able to experience God's presence in my life.

A call for kindness during Kislev. Here is what I have to offer: be kind to yourself during these days. // Pay attention to what your body is saying, to what your heart is saying, to the places where your mind gets tied in knots. What are the stories you tell yourself about this time of year? What are the old hurts to which you can't help returning, what are the old joys which you can't help anticipating? Listen to your body, which is your oldest and dearest companion, and be gentle to it.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers