Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 234

December 27, 2011

Recapturing a family tradition

Roast goose with knedliky.

Many years ago, when my grandparents Isaac and Alice ("Eppie" and "Lali") were still living, their children hired an oral historian to take down their life stories. We have hours of recorded audio (and also a beautiful hardbound transcript, which sets out their stories in print accompanied by photographs.) It's an incredible treasure.

One of the questions the oral historian asked had to do with memories of holidays and food. It's a resonant subject: what do you remember being cooked, in your household, as the major holidays rolled around? For me that list would include the cornish hens and honeyed carrots we used to eat at Lali and Eppie's house at Rosh Hashanah, my mother's kreplach (and her blintzes for break-the-fast at the end of Yom Kippur) -- and her mango mousse (and also cornbread dressing) at Thanksgiving -- and her "chicken Leslie" with artichoke hearts and mushrooms at Pesach.

When the oral historian interviewed them, my grandfather recounted all sorts of culinary holiday memories from Russia. Even outside the oral history context, he used to love to tell stories. About cheder, about accompanying a fellow villager to the market to sell eggs, about learning Latin in gymnasium. And, yes, about food; he was the cook in their family, and food always comes with stories. So he had plenty of stories to tell when the oral historian came to call.

My grandmother, much to my surprise, told the oral historian about eating roast goose (and sometimes carp with a sweet sauce) on Christmas Eve, alongside their tree decked with chocolates wrapped in colored foil. This was in Prague in the 1920s, well before the second World War changed the face of Europe (and drove my grandparents, and their young daughter, to flee in 1939.) My grandfather told endless stories about his smalltown Russian Jewish upbringing; my grandmother was more reticent in general, and didn't talk much (to me, anyway) about growing up as a "kind of Reform" Jew in Prague. The oral history offers me tantalizing glimpses; I wish now that I had asked more questions while she was alive.

This winter, Saveur magazine, to which Ethan and I have subscribed for years, offered a recipe (designed to be prepared on Christmas Eve) for roast goose with chestnut stuffing. "Goose," I said; "I think that's what my grandmother said she used to eat on Christmas Eve as a girl in Prague!" I couldn't resist the prospect of trying to walk, just a little bit, in her culinary footsteps.

So we ordered a goose from Guido's, though we gulped a bit when we discovered how much a 12-lb goose cost. (I suppose the expense just makes the whole thing seem more Dickensian.) Ethan prepared it according to Saveur's recipe. We decided to go Czech with our side dishes, in homage to my grandmother's childhood memories, so we made made zely -- red cabbage spiced with carroway seeds; we also flavored ours with cider vinegar, allspice, and juniper berries -- and knedliky, the Czech bread dumplings my grandfather used to make which were a major part of my childhood foodscape. I helped Ethan form the knedliky, which we boiled wrapped in cheesecloth and then sliced, as is customary, with string.

And on December 24th, after lighting Chanukah candles, we sat down for a festive meal with my in-laws and some close friends of ours (and their kids). Drew, predictably, didn't eat a bite of goose (right now he's emphatically not interested in foods he doesn't already know) -- but we did, and it was delicious, dark and full of flavor. The wild-rice stuffing was fantastic. The knedliky reminded me of childhood. The zely reminded me of visiting Prague. And despite the one broken goblet, and the occasional toddler scuffles over sharing toys, it was a lovely evening -- and while this was probably a far less formal Christmas Eve dinner than the ones my Czech grandmother remembered, it was a wonderful way for me to remember her.

December 26, 2011

Celebrating daughters on the 7th night of Chanukah

In North African countries, the seventh night of Chanukah (1st of Tevet) was set aside as Chag haBanot, the Festival of the Daughters. Mothers would give their daughters gifts, and bridegrooms would give gifts to their brides. Girls who were fighting were expected to reconcile on Chag haBanot. Old women and young women would come together to dance. Another tradition was for women to go to the synagogue, touch the Torah, and pray for the health of their daughters. There might also be a feast in honor of Judith. There was also a custom of passing down inheritances on Chag haBanot. Chag haBanot recognizes that 1 Tevet is a time of receiving the gift of light, and of drawing generations together to honor the birth of spirit within us.

That's from Rabbi Jill Hammer's teachings on Tevet at Tel Shemesh; she also offers a page called Festival of the Daughters, and a Chanukah ritual for the Seventh Night.

I love the idea of celebrating daughters, celebrating girls and women, on the seventh night of Chanukah -- the new moon of Tevet, when the moon begins to wax again, just as (here in the northern hemisphere) the sun's presence in our lives has just begun to increase again.

Even if you aren't interested in a whole celebratory ritual (like the one Reb Jill offers), how might you bless the women in your life as you light tonight's seven candles of Chanukah?

December 25, 2011

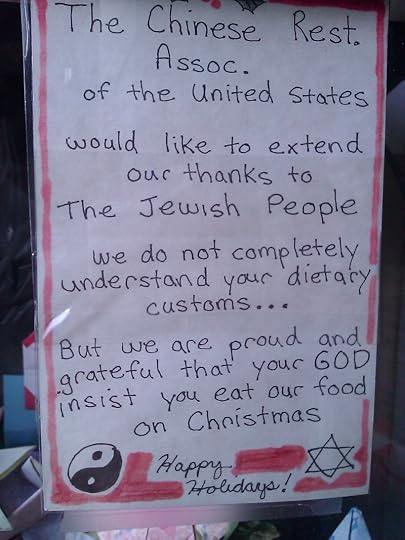

A greeting from the Chinese Restaurant Association of America

From here.

If you observe this traditional Jewish day of going out for Chinese food, I wish you a delicious meal; and to my Christian friends and readers, I hope your Christmas is merry and bright!

December 23, 2011

May the Force be with you!

Via several Facebook friends, I ran across this, which made me grin, so I share it here:

[image error]

Happy Hanukkah to my fellow Star Wars fans; may the Force be with you!

December 21, 2011

AJWS launches Where Do You Give?

(If you can't see the embedded video, above, here's a direct YouTube link.)

American Jewish World Service has launched a new program which I think is pretty terrific. It's called Where Do You Give? The idea is to reimagine tzedakah -- often translated as "charity," though the root of the Hebrew word implies justice, not pity -- through a national design competition and online interactive resources to engage Jews in critical questions about where we give, to whom and why. (For more on tzedakah, check out What is Tzedakah?)

For educators, there's also a Student Track Lesson Plan which uses text, personal reflection, art and student interviews to set the stage for students to design their own tzedakah boxes that express the realities of where, to whom and why they give tzedakah. (Those boxes can then be submitted to the AJWS contest in the secular new year.) The contest actually takes three forms: students can submit an actual tzedakah box, or a digital tzedakah website, or a piece of art or sculpture inspired by these ideas. And the lesson plan is excellent -- I'm planning to teach with it / from it when I return to my b'nei mitzvah students after the Ohalah conference next month.

At this time of year, all sorts of worthwhile organizations tend to clamor for our attention and our wallets, reminding us that in order for donations to be tax-deductible on our 2011 taxes, we need to make them by the end of the secular year. It's true, of course, and many of us do a lot of giving at this season. But I appreciate the AJWS' reminder that tzedakah is an imperative: not only at year-end, not only for tax purposes or because it feels nice to help others, but because God asks it of us. All of us. All the time.

One candle in the dark

Our three chanukiyot.

Today is the first day of Chanukah. Reb Jeff has a beautiful post on The Miracle of the First Day of Chanukah, about the leap of faith involved in having hope.

It's also the winter solstice, or something very near to it -- the shortest day of the year (and the longest night) here in the northern hemisphere. The ritual of lighting one more candle each night is an act of bringing more light into the world -- the light, of course, being both literal and metaphorical. It feels as though, in creating what light we can, we're affirming our part in healing the world, and trusting God to do the same.

May we all be blessed with the ability to hope, and with light in the darkness.

December 20, 2011

Chanukah remixed

Last year around this time, Tablet magazine put out Anander Mol, Anander Veig / Another Time, Another Way, an online album (free for download) of remixes in celebration of Chanukah. Marc Weidenbaum writes:

They are a people, albeit a diverse and dispersed one, spread throughout the world, separated by geography and language, yet still connected through a rich and shared cultural lineage.

I'm speaking, of course, about remixers.

Remixers are electronic musicians who take a pre-existing piece of recorded music and turn it into something else, sometimes something else entirely. They delight in finding choice moments in the original and rearranging what was there until it resembles the source material yet feels wholly new, wholly its own.

As Hanukkah approached this year, I sent a note to various remixers, asking if they'd be interested in selecting a holiday staple, or a song from another festive Jewish event, and taking a stab at remixing it. The response was swift, strong, and positive—as was the supportive response from the musicians and bands who had recorded the originals from which the remixers would subsequently work.

I'm a big fan of remix (it's a form of transformative work which often works well for me), so I thought this was pretty neat. You can listen to the entire album track by track, or download individual tracks or the whole album in one go, at Tablet magazine. Chag sameach / happy holiday to you!

December 19, 2011

Two oldies-but-goodies as Chanukah & Christmas together approach

As we approach the confluence of Chanukah and Christmas, I wanted to highlight two posts from previous years which I think and hope might still be useful or germane:

Mai Chanukah?, 2008: "Chanukah has been different things to different people over time; it's different things to different people even now. That's a lot of layers of context for what is, in the grand scheme of things, a fairly minor Jewish holiday. But the multivalent character of the holiday speaks to something I deeply love about Judaism: that the tradition is always multivocal. That there's always more than one answer to every question. That our interpretations change over time, as our understandings of God and Torah and our relationship with the world change over time. That a holiday which could start out as a commemoration of military victory could turn into a holiday celebrating a leap of faith, into a holiday inviting us to purify our hearts, into a chance to hang out and eat fried foods and sing songs and exchange presents, into all of the above at the same time."

Forest beyond the trees, 2010: "I understand the American Jewish tendency to focus on The Tree, but I'm more interested in the bigger question of how we relate to other religious cultures, especially the majority religious culture within which our various Jewish cultures flourish. For me, the question of whether having (or enjoying) a tree diminishes one's Jewishness is beside the point. Jewish identity shouldn't be so fragile that a decorated evergreen can shake its foundations. At this season, we can become so fixated on the matter of the tree ("to trim a tree or not to trim a tree" -- is that really the question?) that we lose sight of the forest beyond it -- which is to say, the bigger religious picture of the year, of which December is only a small part."

Enjoy!

December 18, 2011

Brettler and Levine on the Jewish Annotated New Testament

On Saturday evening I drove south to Great Barrington, to hear Dr. Marc Zvi Brettler and Dr. Amy Jill Levine speak about the Jewish Annotated New Testament at Hevreh of Southern Berkshire. (For background, here's the article I just wrote for the Berkshire Eagle: Jewish scholars give perspective on the New Testament.)

When I arrived, shortly before six, the parking lot was full; I had to drive further down to the overflow parking lot! The place was totally packed -- hundreds of people were present. (Midway through the event, someone asked any Christians present to raise their hands -- I'm guessing about a quarter of the room was Christian.)

Our speakers were introduced by Rabba Kaya Stern-Kaufman, a member of Hevreh and also a member of the Berkshire Minyan which meets at Hevreh. The evening was co-sponsored by Christ Church Lutheran, St James Episcopal, Congregation Beth Israel, Jewish Federation of the Berkshires, and the South Berkshire Friends Meeting.

"On this Saturday night I am struck by the fact that we are sitting together on a kind of bridge in sacred time. Saturday night marks the end of the Jewish Shabbat and precedes the Christian Sabbath. Resting on this bridge together, we are graced with a unique opportunity," said Rabba Stern-Kaufman. The Jewish Annotated New Testament, R' Stern-Kaufman said, "deepens the possibility of understanding and healing" between Judaism and Christianity.

Marc Zvi Brettler

When many people see the title of the book they think that this is a controversial book, noted Marc Brettler. The first blog entry he saw about the book began thus, "Without having read it, and I can guarantee you I never will, I can guess it's a new bold attempt by the rabbinic Talmudists to undermine the faith." (Looks to me like this is actually a comment on someone else's post.) Meanwhile, the first review on Amazon read, "It is evil for Christians to try to convert Jews...why don't you people leave us in peace?" You just can't win, he joked. But more seriously -- "we just could not find a better title for the book!"

Oxford University Press discovered long ago, he explained, that Bibles sell well. Fifteen years ago OUP was revising its standard college and church Bible, the New Oxford Annotated Bible, and the main editor contacted Brettler, saying that he wanted someone to be involved who was not Christian, in order to ensure that the newer editions would not draw the spurious distinction between the Old Testament God of law and war and the New Testament God of grace. A few years later came the Jewish Study Bible, in which the Hebrew Bible was commented-on by Jewish scholars -- it was remarkable, Brettler noted, that there were finally enough Jewish scholars for that volume to happen!

After he finished co-editing that, he said to his editor, partially in jest, "what would you think about a bunch of Jews getting together to do the New Testament the way we just did the Hebrew Bible?" It took his editor a few years to talk the rest of OUP into it, but here we are.

"I think this book is important to different people for various different reasons," Brettler noted. "I am tired of hearing people talking about the Judeo-Christian heritage of America, implying that Judaism and Christianity are more or less the same thing!" He cited the book The Myth of Judeo-Christian Tradition and said he wished it were more widely-read. "Part of what worries me about this term, Judeo-Christian, is that it is often used in a pernicious sense, to exclude Muslims in various ways," he noted. And then, for a laugh, he held up the bumper sticker someone had sent him -- the fish with feet (Darwin-fish style) which reads "Gefilte."

Brettler continued:

I hope that we are able to respect each others' scriptures, which are different in a variety of ways, and that we can come to understand each others' scriptures... and get a sense for what the commonalities, as well as the differences, are.

Another reason he was involved with this book, he told us, is that he knows many Jews who have never even cracked the NT, for fear that we would be proselytized-to the moment we opened up the introduction. That got a rueful laugh from the room. Next time you're in a hotel which has the Gideon Bible in the drawer, he challenged us, open it up and read the introduction -- "you'll learn a great deal about the way in which certain Christian versions of the Bible have been written!" For these reasons, among others, he felt it was important to put together an edition of the NT which Jews would not be afraid to open.

President Obama, in his inaugural, said, "in the words of scripture, the time has come to set aside childish things." Dr. Brettler told us that when the President said that, everyone in the room looked at him, and he just shrugged his shoulders -- "I'm pretty sure it's not in the Hebrew Bible!" Unless you understand Paul and his letters to the Corinthians, you're not going to understand an important influence on American culture.

Also, he noted, the New Testament and Christianity have deeply influenced Judaism. R' Arthur Green wrote an article several years ago called "Shekhinah, the Virgin Mary, and the Song of Songs." (Here's an abstract.) Shekhinah, he explained, is Hebrew for the presence or manifestation of God as it is understood in kabbalistic literature, and Shekhinah is a feminine-gendered noun. Arthur Green made the claim that the medieval interest in Shekhinah was influenced by the Catholic interest in the cult of Mary -- a controversial claim at the time, though today many of us might take it for granted.

Or take the Hebrew expression ayn navi b'iro, there is no prophet in his own city. Most sources call this a Jewish expression or phrase. But this is a rabbinic borrowing from Christian texts! "I do not mean to suggest that religion needs to be understood only in terms of what external forces have influenced a particular religion, but that is one important aspect of understanding religion, and surely Judaism has been influenced by Christianity in a variety of ways."

There was interest by Christians in the Hebrew Bible and other Jewish works during the Renaissance. Many of the leading Biblical scholars at that point were Christian scholars who had begun to study Hebrew. "If non-Jews are able to study the Hebrew Bible, which was originally a Jewish work, is it not fair that there should be some reciprocity, that Jews should be able to study the New Testament as well?" It is valuable, he argued, for Jews to be interested in Christian literature, "especially since a strong knowledge of rabbinic material often adds insight into what New Testament texts mean."

He cites Matthew 22 verses 34 and following: "When the Pharisees heard that Jesus had silenced the Pharisees, and one of them, a lawyer" -- what does the NT mean by lawyer, by the by? surely not someone who had passed the Palestinian Bar exam! -- "asked him a question to test him, 'Teacher, which commandment in the Law is greatest?' He answered, You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind. And the second is like it: you shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets." You might think this was a very Christian idea, a very Christian understanding of the Hebrew Bible.

But it's not. Or at least, it's not only a Christian idea. Quoting from the Talmud Yerushalmi, Dr. Brettler notes -- "R' Akiva taught, love your neighbor as yourself (Lev 19:18) - this is the most important rule in the Torah." He pointed out the similarities between the New Testament teaching and the Talmudic tradition; and secondly, he argued that anybody who wants to draw a contrast between Christianity as a religion of love and Judaism as a religion of law would do well to remember this passage from Talmud where Leviticus 19:18 is called "the most important rule in Torah."

"It is possible, even important, to be a religious believer, but nevertheless to admit that there are problems with your core religious text." If he had a chance to re-do the Hebrew Bible, he knows which 25 chapters he would take out of it! "I am tired of certain apologetic attitudes which de-problematicize...the problems we have in our Scriptures need to be confronted head-on."

It is as useful to complain about Galatians 3:18 and similar text -- "wives, be subject to your husbands" -- as it is to complain about the last few words of Genesis 3:16, "and he will rule over you." And of course the reverse is true, he noted, as well. "One can, and I would argue one must, find beauty and meaning wherever it is present." Influenced, he told us, by teachers like Krister Stendahl, he has learned to see the beauty in the Christian scriptures.

In the editorial process, Dr. Brettler's interest was primarily connections between the Hebrew and Christian scriptures and between the Christian scriptures and the early Talmud; Dr. Levine's interest was primarily the Christian scriptures themselves. It sounds like this was a good balance; often, he told us, concepts which had seemed obvious to the essays' authors were not obvious to him as a Jewish reader.

Sometimes, he told us, concepts which play a minor role in the Hebrew scriptures become major ideas in the New Testament. The idea, e.g., of the fall of man and original sin -- we think of these as Christian ideas, but actually these build on Psalm 51, "Indeed, I was born with iniquity, with sin my mother conceived me." Certain ideas which might be peripheral, hardly mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, become very important in this later literature which takes the Hebrew Bible so seriously.

And then, in a nod to the Hebrew Bible format of the inclusio, he chose to end as he had begun, with two blog comments. One of them is, "This book is a serious Jewish analysis of the NT. Timely -- no, overdue."

Amy Jill Levine

"My professional activity is in New Testament," she explained. Her primary job at Vanderbilt Divinity school is to train Christian divinity students on how to read the New Testament -- "an odd job for a Jew, but somebody's got to do it!" Her introduction to Christianity was ethnic Roman Catholicism and she loved it: parades of statues through the streets, fabulous foods, going to Mass with her friends after roller-skating -- "it was like going to synagogue; it was a bunch of men in robes speaking in a language I didn't understand. I found it absolutely fascinating!"

Her parents told her that Christians and Jews both worshipped the God of creation, that we pray many of the same prayers, that we share a sense of the importance of at least the Ten Commandments, and that a Jewish man named Jesus was very important. "So my initial sense was that the church was the synagogue we didn't attend." Her fascination with Christianity came to a head in second grade when all of her friends were preparing for First Communion -- she too wanted the dress, the veil, and the white patent leather purse! (That got a good laugh.) Midway through that same year, she heard from a little girl on the school bus, "You killed our Lord."

That, she told us, was her first lesson in interfaith relations. "It turns out we don't know enough about our neighbors' religion to know what to even ask. So we simply presuppose."

Shortly after that came Nostra Aetate, which proclaimed that Jews in all times and all places cannot be held responsible for the death of Jesus. But this encounter on the school bus was before that. "I could not understand how a tradition that had the same God and the same prayers and a Jewish man named Jesus, not to mention Santa and the bunny, both of which I liked, could say horrible things about Jews." She decided, even then, at seven years old, to go to CCD, figure out where the antisemitism was coming from, and stop it. Her parents said, "As long as you remember who you are, go; you might learn something." So she did.

And, she told us, she fell in love with the stories -- and noted their common ground with the stories from Tanakh which she already knew. Jesus meets women at the well; so did Abraham's servant Eliezer when he found Rebecca. Jesus makes food appear miraculously, heals people, raises the dead; so does Elijah the prophet, so does Elisha the prophet, so do the miracle-working rabbis who multiply food and heal people! Jesus survives when children all around him are slaughtered (Matthew 2) -- and we too have a little baby boy rescued when all the little boys around him are slaughtered, who has a connection with Egypt, crosses water for a life-changing experience, and goes to a mountaintop to deliver the law. (That'd be Moses.)

She looked for antisemitism in the teachings of Jesus, and found, "Woe to you scribes and pharisees, because you like to be greeted with honor in the marketplace and you like to have the best seats in the synagogue." But to her, this sounded exactly like something her mother might say about some of the big machers at their shul! (Another good laugh line.)

In seriousness, she told us, there are passages in the NT which are problematic. There are passages which have caused the deaths of millions of Jews, "and we flagged them in the book." But as she read them, it occurred to her that her Catholic friends, the people who had taught her catechism, did not read the text that way. And the same holds true for Jews and how we relate to what's problematic in our scriptures. "We Jews read about the awfulness of the Egyptians during the Passover story, but that doesn't make us hate Egyptians -- I would date Omar Sharif, given the opportunity!" (That too got a laugh.) The important thing to bear in mind is, we all choose how to read our texts. So in this book, she told us, they sought to draw attention to the difficult passages and also to explore how people have read and interpeted those passages through the centuries.

"Much of the NT is written by Jews," Levine noted. "The only first-century Pharisee from whom we have written records is Paul of Tarsus. Paul wrote 7 if not 13 NT documents...the more we know about first-century Judaism, the more we know how well he fits into the first century." There was great diversity of theological beliefs in the first century; what was possible in Judaism in the year 40 becomes impossible by the year 400.

"The first person in history ever called 'rabbi' is Jesus of Nazareth, and his statements make a great deal of sense in a Jewish context. The NT becomes for us a marvelous source of Jewish history," said Levine. It's a particularly good source for learning about the history of Jewish women in the first century of the Common Era.

The hope here, she told us, is to help Jews as well as Christians understand how this book functions culturally, without fear of proselytizing.

Levine added:

As a Jew, I want Christians to respect Judaism, which means knowing more about us than Adam Sandler's Hanukkah song! But if we want Christians to respect us, that means we need to respect them -- and that means we need to understand what's in their scriptures.

She and Brettler were also interested in correcting uninformed Christian misinformation. "I hear from my divinity students all kinds of nonsense about first-century Judaism, and it is my job to correct it." Most of the troubling rhetoric about Jews in Christian thinking comes not from antisemitism but from ignorance, she told us.

Levine mentions the essays at the back of the book -- which I have begun to read, and which I think are fantastic, by the way -- as one of the primary ways in which this book can correct misinformation. "When I was first reading the NT, it occurred to me, this is Jewish history!...By having Jews do the annotations for this book, in effect, we're reclaiming our history."

On a personal note, she told us, she spends a lot of time doing interfaith relations. "What this text can do is help build bridges." She also mentions interfaith families. How can Christian grandparents with Jewish grandchildren, or vice versa, talk with one another? Perhaps this book can help us "reclaim our common roots and celebrate them, and also see how and why we differ."

After brief remarks from a local Christian minister, we moved into a question-and-answer period. Questions ranged from "which version of the New Testament did you use?" (the NRSV) to "when you see verses taken out of either holy book, do you get the sense they are used by people for power and control, instead of for study and for God?" ("Yes, absolutely," said Levine. "We're Bible-saturated in the United States but we're biblically-illiterate...so people yank the text out of context.")

Someone else asked, how did your work on this book effect and change you? "It took four years of our life," Levine quipped. "Some of it was like herding cats!"

But she added, "Did it change my faith? No. But what it did do is give me greater respect for the areas of connection between the Jewish tradition and the Christian scriptures, connections in the thought-world between early Christianity and early Judaism."

I was also impressed by Levine's comment about how she tries to teach the NT with the utmost respect not only for its original audience and setting but also for the people for whom this text remains sacred scripture. She doesn't need to believe in it in order to teach it in that way. And as a result, when the Christian divinity students have a crisis of faith, they come to her, because if she as a Jew can find the holiness in their scripture and their teaching, kal v'chomer, how much more so might they be able to learn to find that holiness again. What a lovely response.

There was also a question about Revelation and the beast whose number is 666, to which Levine's response delved both into apocalyptic literature and into the practice of gematria; anyone reading that text in the first century would have known the gematria of the emperor Nero, and would have read that as a hidden reference to the emperor, but that symbology has largely been lost to us, and "each generation reads the text anew."

And Revelation isn't actually all that unique, in a certain way. "If you read the entire Hebrew Bible, which very few Jews have, you're aware of the last six chapters of the book of Daniel," added Brettler, which was written right before the Dead Sea scrolls were written, and was an instant best-seller in its time, because that kind of apocalyptic material was hugely popular at the time. "Now we know that at that same period when rabbinic literature was coming together, there was mystical and apocalyptic literature which makes Revelation appear tame." Within Judaism, at certain points, that type of literature was squelched; but it is also part of the Jewish tradition, as it is part of Christian tradition.

The last two questions were about the possibility of mis-use of this text by, e.g., Jews for Jesus (the editors agreed that they want this text to be used in whatever ways are helpful, and that they're not sure that what was described in the question would constitute a mis-use) and about language (yes, the editors and the authors frequently turned back to the original Greek and the original Aramaic, especially the Aramaic and Hebrew antecedents of the Greek words, which can draw out additional meanings in Jesus' teaching.)

"This is a commentary written by professionals," Brettler noted, "so the original languages are very important -- but on the other hand we were both very committed to making this type of scholarship acessible to anyone who wants to read it."

Nu: I'm really glad I schlepped to south county. Despite my general tiredness at this moment in time, it was worth staying awake the hour in the car. I'm so glad to have been present for this conversation and to have a copy of this book in my rabbinic study.

December 15, 2011

Article in the Eagle about the Jewish Annotated New Testament

BECKET -- Becket resident Marc Zvi Brettler, co-editor with A.J. Levine of The Jewish Annotated New Testament (Oxford University Press, 2011), never expected a best-seller -- but the first printing sold out within days of publication.

This is the first edition of the New Testament to appear with marginal commentary and interpretive essays by Jewish scholars. It places the Christian scriptures within their original Jewish context, and it also faces the questions of how the two traditions have interpreted these texts over the centuries -- and the tensions which those differing interpretations have sometimes perpetuated.

That's the beginning of an article I just published in the Berkshire Eagle, after I had that chat with Marc Brettler.

Like "The Jewish Study Bible," this volume contains both annotations of Scripture and a set of essays which put the material in context: essays on early Jewish history, Judaism and Jewishness and the notion of "The Law." Writers explore the Greek term "Ioudaios" -- translated as either "Jew" or "Judean" -- and its implications. They consider the concept of the neighbor in Jewish and Christian ethics. They try to understand of John's "Logos," the "Word," as a kind of midrash -- a form of storytelling, which explores interpretations of, loopholes in, and questions about scripture.

"Figuring out what Jewish readers, Christian readers, and other readers should understand -- and then finding people to write about those subjects -- That was intellectually very interesting," Brettler said.

I'm looking really forward to hearing the editors of this volume speak on Saturday evening at Hevreh. Meanwhile, my thanks to the editors at the Eagle for inviting me to interview Marc! You can read the whole article here: Jewish scholars give perspective on the New Testament.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers