Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 228

March 22, 2012

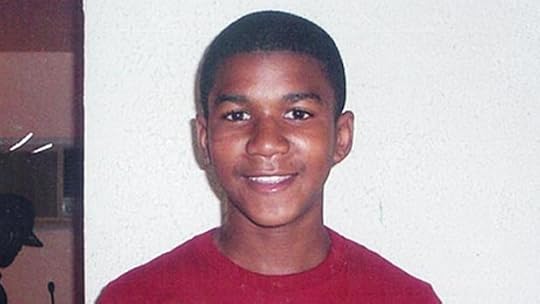

Mourning for Trayvon

Trayvon Martin, zichrono livracha / may his memory be a blessing.

This is a heartbreaking one.

Trayvon Martin was seventeen when he was killed last month by a 28-year-old named George Zimmerman, who most sources are calling a neighborhood watch captain though the National Sheriff's Association has said that he was not associated with an official neighborhood watch. (In case you're wondering, no, George Zimmerman is not Jewish.) Trayvon was unarmed. He was carrying a bag of Skittles candy and a bottle of Arizona Iced Tea. George Zimmerman saw Trayvon walking; he called 911 and reported Martin as "a real suspicious guy," adding, "This guy looks like he's up to no good or he's on drugs or something." Against the protests of the police (who told him not to pursue), Zimmerman chased him, shot him, and killed him.

As far as I know, Zimmerman has not been arrested or charged with anything. Because of Florida's "stand your ground law," his claim that he acted in self-defense stands. This despite the fact that recently-released recordings, including Trayvon's last cellphone call with his girlfriend (moments before his death), appear to contradict that self-defense claim.

And Trayvon Martin's parents have lost their son. Because he walked through his father's gated community neighborhood (Trayvon lived in Miami, but was visiting his dad in Sanford at the time), and apparently the culture of racism in this country is so deep that simply being a young black man in a hoodie sweatshirt can get you killed.

In her recent post What is white privilege, Emily Hauser writes:

I think I know what white privilege is.

White privilege is never being frightened for my son's life, simply because of the color of his skin.

I'm right there with her. I have a son. He's two. He has rosy cheeks and flyaway blond hair. He loves his Thomas train set, playgrounds (in spring and summer), making snowballs (in winter), sitting in my lap while I read Knuffle Bunny or The Going to Bed Book, and going to the bakery on Friday afternoon to get challah and a cookie before Shabbat. I love him so much I don't have words to express it. And I know that because he is white, neither an armed vigilante nor a police officer is likely to shoot him under the mistaken impression that he's a criminal.

My heart goes out to Trayvon Martin's parents, and to the parents of every child who is killed because someone's unconscious stereotypes caused them to imagine a threat where none existed. Source of Peace, bring them peace along with all who mourn. Help us to shake off the spiritual ennui, the compassion fatigue, the unknowing racism which allows this to be our nation's status quo. Raise up our anger. Wake us up. Help us change. For Your sake, and for ours.

God, full of compassion, grant perfect peace under the wings of Your presence to the soul of Trayvon Martin, who has entered eternity. May he rest in peace.

For further reading:

The Trayvon Martin Killing, Explained, Adam Weinstein, in Mother Jones

Trayvon Martin's death: the story so far, in the Guardian

Where's white church outrage over Trayvon Martin, Mark Pinsky, on the CNN belief blog

What a Florida Teenager's Death Tells Us About Being Black in America, John McWhorter, The New Republic

Bedside

It is humbling to sit by the bedside of someone who is transitioning out of this life.

Sometimes their breathing is labored. Sometimes there is the "death rattle," a kind of guttural rasping with each inhalation.

Often their skin begins to seem almost translucent. The Hebrew word for skin and the Hebrew word for light are homonyms.

Often as I touch their arm, or stroke their forehead, I remember extending that same gentleness to someone who has died.

I say, It's Rabbi Rachel. I'm here with you. Your loved ones are here with you.

I say, let go of any old stuff, any anger or frustration, any baggage between you and anyone else. You don't need it anymore.

I say, we're letting go of our issues with you, too. We love you. Whenever you are ready, you're free to go.

I sing the angel song. I think of the illustrations in the bedtime shema book, sweeping watercolors showing Wonder and Strength, Light and Comfort, the angels who accompany each of us into sleep.

I sing the niggun which asks why a soul incarnates in this world, and which answers that we enter this world in order to know God. A funny thing, isn't it? We think of God as being beyond this world, and yet the way to know God is to be in the world. We have to be apart in order to yearn to be together.

When we leave this world, maybe we return to that intimate connection. I believe we do.

May angels accompany you, dear one, through this passage into what's coming. We love you. We're here. You are not alone.

March 20, 2012

On bodies, blood, and blessings

Here's a question I've been asked but have never known how to answer: is there a blessing for menstruation?

I've been thinking a lot lately about the ways in which American culture teaches women to have negative feelings about our bodies. One of the subtle ways in which this happens, I think, is in the shame we're taught to feel about even mentioning menstruation, much less experiencing it.

People generally don't talk about menses in polite company. And when we do, we use euphemisms. (When I was a teenager, people said "on the rag." I'm not wild about that term, though it's slightly better than the curse.)The point, though, is that it's not a curse. Each month when my uterus sheds its lining, that's a sign that new life isn't growing in my womb this time around, but that doesn't change the reality that my body can be a home for new life, and that's incredible.

There are times when menstruation can be a heartbreak. For women (and their partners) who struggle with infertility or experience miscarriage, who yearn for a pregnancy, the monthly return of bleeding can be a source of tremendous sorrow. I remember the first few periods after my miscarriage. The bleeding and the cramping reminded me of that awful morning in Colorado when I had woken to discover my pregnancy over. I don't want to gloss over that.

But that doesn't make the bleeding itself wrong, or gross, or something to be ashamed of. This is something which cis-gendered women -- half of the human population! -- experience every month from puberty until menopause, except when we're pregnant (and, for some women, during the early months of nursing). Our wombs grow the stuff they would need to support a fertilized egg, and then when no egg implants, our wombs naturally let that stuff go. This is a natural part of life, no more "gross" than birth or death -- both of which, granted, may be scary, but to my mind anything which connects us with birth and death is by definition holy.

Birth and death (and, by extension, blood) offer opportunities to connect with something deep and meaningful, something far greater than ourselves. This is, I think, one way to understand Torah's language around taharah and tum'ah. It's not a matter of being "pure" or "impure." When I am not in contact with birth, death, or blood, I am tahor: a spiritual blank slate. When I am in contact with these things, I become tamei, charged-up with a kind of holy energy, vibrating at a different frequency for a little while because I have touched something beyond. (This is not, by the way, a new idea; I've written about it before, drawing on a number of prominent theologians and interpreters who make this case.)

There's a lot of talk lately in the American public sphere about women's bodies and women's health. I recommend Emily L. Hauser's Dear GOP: You do know how pregnancy works, right? (and, for a bigger-picture look at how our culture speaks to/about women, her post Like a girl) and Jessica Winters' recent essay Are Women People? (also Catherine MacKinnon's scathing Are Women Human?, written in 1999 but still powerful) as well as the excellent series of recent Doonesbury cartoons which some newspapers have published on the Op-Ed page instead of the cartoon page. (Here they are: Part one, part two, part three, part four, part five, part six.)

Watching these debates unfold, I find myself wondering whether the world might be a better place if we celebrated women's bodies instead of allowing ourselves to be made ashamed.

So is there a bracha for menstruation? Rabbi Elyse Goldstein asked that question (see her essay Reappropriating the Taboo at My Jewish Learning), and came up with an answer I think is pretty neat. When she bleeds each month, she recites the blessing

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ אֶלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, שֶׁעָשַׂנִי אִשָּׁה / Baruch atah Adonai, eloheinu melech haolam, she'asani ishah:

Blessed are You, Adonai our God, Ruler of the Universe, who has made me a woman.

In a traditional Orthodox prayerbook, as part of the series of morning blessings recited each day, men are instructed to thank God for not making them women, and women are instructed to thank God for making us according to His will. In most liberal siddurim, we find instead a single blessing -- intended to be recited by people of all genders -- which thanks God for making us in the divine image. But I love Rabbi Goldstein's idea of sanctifying menstruation by actively thanking God for making me a woman, using this twist on these very traditional words.

I make the asher yatzar blessing when I go to the bathroom. If I can aspire to sanctify even that act, surely I should aspire to sanctify my body's potential to nurture new life -- and my body's ability to let that potential go.

If you're interested in this subject, don't miss Kohenet director Taya Holly Shere's writing on sacralizing menstruation, which is excerpted in Jay Michaelson's book God In Your Body.

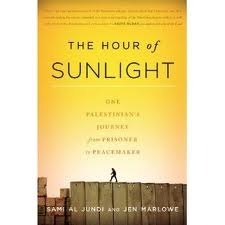

Book review: The Hour of Sunlight

I just finished The Hour of Sunlight: One Palestinian's Journey from Prisoner to Peacemaker by Sami Al Jundi and Jen Marlowe. I picked the book up on Emily Hauser's recommendation, and I'm so glad I did.

Here's how Amazon describes the book:

As a teenager in Palestine, Sami al Jundi had one ambition: overthrowing Israeli occupation. With two friends, he began to build a bomb to use against the police. But when it exploded prematurely, killing one of his friends, al Jundi was caught and sentenced to ten years in prison.

It was in an Israeli jail that his unlikely transformation began. Al Jundi was welcomed into a highly organized, democratic community of political prisoners who required that members of their cell read, engage in political discourse on topics ranging from global revolutions to the precepts of nonviolent protest and revolution.

Al Jundi left prison still determined to fight for his people's rights—but with a very different notion of how to undertake that struggle. He cofounded the Middle East program of Seeds of Peace Center for Coexistence, which brings together Palestinian and Israeli youth.

Marked by honesty and compassion for Palestinians and Israelis alike, The Hour of Sunlight illuminates the Palestinian experience through the story of one man's struggle for peace.

This book wasn't always easy for me to read, but it is powerful and it is worth reading, especially for anyone who (like me) may have more access to Israeli narratives about the Middle East than to Palestinian ones.

The book opens with poignant vignettes about Sami's growing up, his yearning to live in Zakariyya (his mother's home village, now Moshav Zecharia) and to have known the Deir Yassin of his father's childhood, his experiences as the son of two blind parents. Here's a taste of his childhood, after he's asked his father for a pair of shoes he knows his family can't afford, and to his surprise his dad has said yes:

I ran right to the shoe store on Salah el Din Street. But my stylish new footwear brought me little satisfaction. My mother was sick, my father had eight children to feed, Samir would be starting college soon, and I had just bought myself a pair of fancy boots to be like my friends. The image of my father's face as he handed me the money floated in front of my eyes. I forced myself to wear the boots every day, swearing never again to ask my father for anything expensive.

Little stories like this one make his childhood something to which foreign readers may be able to relate.

Of course, even the early part of the book isn't simply childhood anecdotes; the clash between Israel and the Palestinians is always already present. His friends are becoming increasingly involved in the struggle against occupation, and as he grows, Sami is, too. Ultimately he joins two of his teenaged friends in making a pipe bomb which they intend to plant at a fruit and vegetable market -- a story which is not easy for me to face by any stretch of the imagination. But even as he's treading this ground, he's also working at an Israeli sandwich shop and developing a crush on a young Argentine Jewish woman who's in the process of making aliyah. His relationship with Israel and Israelis is always already complicated.

As the astute reader likely already knows, the pipe bomb goes off while they're building it. Sami and the one friend who survives both wind up in prison (after an interrogation which definitely crosses the border into torture; that part was hard for me to read, but I understand why it's there. And, in fairness, Sami turns the same clear lens and angry eye on the Palestinian Authority police who later abuse their power and beat him up, too.) Once he enters Israeli prison -- colloquially known as "university," because of the system of self-improvement and education developed there by Palestinian political prisoners -- the book becomes doubly fascinating and moving to me. He writes:

Books expanded my world far beyond the prison walls. I read an average of three hundred pages each day. History, psychology, and philosophy were the serious studies. Poetry, romance stories, and French and Arabic literature were my escape. Writers were like prophets to me. Their characters dwelled inside me as if their experiences were my personal memories. I often crouched against the door of the cell until the small hours of the morning, book in hand, to make use of the small, striped square of light spilling in from the corridor.

Sami describes the prison community, the bonds which form among the political prisoners, the discussions and conversations. He also recounts the hunger strikes for better living conditions, the experiences of mistreatment and suffering, the experience of becoming an "elder" prisoner who is now tasked with teaching the newbies when they arrive. He writes about his unease with being expected to teach Fatah ideology; even while Fatah leaders were beginning to move toward a peace negotiation process, their prison curriculum inside the Israeli prison system was still focused around armed struggle. He writes:

I wanted to teach my students about Gandhi. I was drawn to the idea of "White Revolution," the phrase we used for Gandhi's tactics against the British occupation of India. I wanted them to read about the Hindu man who came to Gandhi, blood still staining his hands from having murdered a Muslim child. Gandhi instructed the man to find a Muslim orphan of the same age and raise him, providing him with a father's love and an Islamic education for twenty years. I had contemplated the anecdote for months when I first encountered it. How easy it was to destroy a soul -- the baby had been murdered in a matter of moments -- and how much time, effort, and love was required to build a soul.

Sami learns not only from his fellow prisoners, but from his family. His blind mother, he learns, has been spending her Fridays visiting prisoners from Lebanon who have no one to visit them; visiting the elderly and infirm in the Old City on Sundays; and going to Hebrew classes on Monday nights, because, as she says, "I have to understand what the soldiers are saying when the other women and I protect the kids from being arrested during demonstrations."

Probably the most moving part of the book, for me, begins once Sami is out of prison and slowly beginning to form relationships with Israelis despite the tremendous difficulty involved in finding common ground. His friends, who have been involved with the struggle for Palestinian liberation, don't entirely understand what he's doing or why; but, he writes:

From the moment I had stepped into Muriel's apartment with Israelis and Palestinians ready to sit together and really talk as equal human beings, I had felt, for the first time in my life, as if I had come home.

Sami becomes involved with the Seeds of Peace Center for Coexistence, where he meets co-author Jen Marlowe. They write beautifully about that journey. That part of the book brings me both joy (watching Sami's trust and hope grow) and also inevitably sorrow (because I know, reading this now, that the changes for which he hopes have not yet come to pass.)

Through Sami and Jen's narration, I watch as Seeds of Peace changes and matures. We see Israeli and Palestinian kids, whose initial friendships have been nurtured at a summer camp in Maine, beginning to interact "back home" as well. We watch as Palestinian kids visit Israeli homes for the first time -- and vice versa. We watch as Sami is invited to his first Pesach seder (a scene which is particularly moving for me for a variety of reasons.) We watch as the Israeli and Palestinian kids come to love and understand one another. At the height of this section of the book, the kids travel together, in their green Seeds of Peace t-shirts, to Jordan to see Egyptian singer Ehab Tawfik -- who sees them in their matching garb, asks who they are, and then after a tense moment, urges the enormous crowd to join him in chanting in support of peace.

And then Ariel Sharon heads for the Temple Mount, and the second Intifada begins, and it all falls apart. Violence mounts. Suicide bombings intensify; border control becomes tighter and Palestinian kids can no longer enter East Jerusalem. Some Seeds in Gaza make video messages for their Israeli counterparts, trying to explain their shattered lives. Some Israeli Seeds, for their part, struggle with whether and how to do their compulsory army service. One Palestinian Seed, a boy named Aseel Asleh, is killed by Israeli police during a peaceful demonstration -- wearing his green Seeds of Peace t-shirt at the moment of his death. (Jen Marlowe has since written a play about Aseel's life and death, called There is a Field.)

I devoured the earlier part of the book; I found this latter part of the book painful enough that it took me several days to my work my way through it. I didn't want to watch as the dreams of peace and coexistence which Sami and his colleagues had nurtured were dashed and destroyed. Reading that felt like reliving the experience of slowly watching the peace process disappear.

That said, the book still manages to end on a note of hope. I come away deeply glad to have read it, and glad to have gotten to know Sami through this literary medium. As Jen writes in her introduction,

Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about Sami is his unshakeable belief that not only is it possible for Israelis and Palestinians to live together on this land, but that both peoples would benefit from the presence of and relationship with the other.

May it truly come to pass, speedily and soon.

If you'd like to learn more before buying a copy, there's a brief excerpt from the book at Spirituality & Practice, and the co-authors are interviewed on GRITtv.

Signal-boost: Ethiopian tallitot for a good cause

If you were reading this blog back in 2008, you caught glimpses of the summer I spent living in Jerusalem. While I was there, I shared an apartment with my dear friend Yafa, her husband Harley, and their daughter Ariel, who was then three and a half.

Yafa and I were ordained together last year. (Here's an article about her from what was then her local newspaper: For Rabbi Yafa Chase, all signs lead to service.) Since then, she and her family have spent several months in Ethiopia -- where she has lived and worked before -- following the vision and the intuition which told her that there was a son waiting for them there. For now they're back in the States -- they returned for Yafa's mom's funeral -- but they have fallen in love with a little boy named Samuel, and hope to bring him home soon.

Meanwhile, they want to do something to give back to the community of orphan children there. Enter Buy a Tallit, Help Orphans in Ethiopia. On that website you can read their story in Rabbi Yafa's own words; you can see images of the Ethiopian-loomed tallitot (woven by a collective of weavers in Gondar) which are for sale; and you can either buy one for yourself or as a gift, or simply make a donation.

Please consider helping my friends do something kind for children in need.

March 19, 2012

Norouz Sameach! and Israel ♥ Iran

Norouz is the Persian new year, which is happening right now. (I've blogged about it before, a little bit.) The above image reads "Norouz Sameach" -- "Happy Norouz" in Hebrew. I found the image in a post at Israel Loves Iran (which in turn I found via a post at Mystical Politics).

If you have a few minutes to spare, I recommend browsing the gallery of images at Israel Loves Iran. All of them were submitted by Israelis who want to send the message that they feel only warmth and kindness toward Iran and that though the Israeli government is pretty belligerent toward Iran these days, it doesn't represent everyone in Israel. The image campaign was started by Ronny Edri and Michal Tamir; while the original flurry of images came from Israelis (for Iranians), Iranians are now responding in kind. Pretty cool.

Anyway. To those who are celebrating Norouz, happy new year! May the coming year be sweet.

March 18, 2012

Vayikra: divrei Torah on the first parsha in Leviticus

This week we're entering the book of Vayikra, known in English as Leviticus. A lot of people cringe a little when we reach this part of the Torah: so many details of sacrificial offerings, this part of Torah may feel distant from us.

But in one traditional paradigm, this book of Torah is what's taught first when we begin teaching Torah to our children. It's (quite literally) central to Torah -- book 3 of 5, this one is in the very middle. And there's some wonderful stuff here.

For those who are interested, here are the divrei Torah I've posted on this parsha in previous years:

2006: Unleavened offerings of our hearts (originally published at Radical Torah)

2007: The heart of things (originally published at Radical Torah.)

2008: Korban [Torah poem] (now published in 70 faces)

2011: Thinking about sacrifice

If you're looking for more context, I can recommend Leviticus at My Jewish Learning, an essay by Baruch Levine which offers a good overview of this book of Torah. And, for a different take on the parsha, I recommend Reb Jeff's weekly Torah post this week -- Vayikra: The Joy of Contrition.

Enjoy!

Shabbos!

With David, last summer at the 2011 ALEPH Kallah.

What a treat this past Shabbat turned out to be!

My dear friend Reb David came to visit, and together we led davenen (prayer) at my shul. We'd realized, early on, that Saturday was going to be St. Patrick's Day, and we wanted to mark that in some way. "We should set a piece of liturgy to the tune of something Irish," I emailed him. "What Irish melodies do we know?"

A few hours later, I got an email in return featuring an mp3 of David singing "Mi Chamocha" to the tune of "O Danny Boy." I laughed. And then I wrote back promising him that we would do it, for sure. When else in my life was I likely to get that opportunity?

As it happened, we had special visitors this weekend: a handful of folks from the Greenfield shul up the road. Between their added energy, and the assembled folks from my community, we had quite a little crowd!

Leading with David was a joy, as always. He played keyboard; I played guitar. We brought a few melodies which were new(ish) to my community -- R' Marcia Prager's setting of "Mah Tovu" (which may be the only tune I know in 13/8), R' Hana Tiferet Siegel's setting of "Ashrei" -- and also repurposed a few from elsewhere, like Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah" (which we used for Psalm 150) and, on a suggestion from the kahal, the classic "When the Saints Come Marching In" (which we used for "Adon Olam.")

This week's Torah portion was the very end of the book of Exodus. As soon as it was over, we broke into song -- the melody for "Chazak chazak v'nitchazek" which we'd taught earlier in the morning. David offered a d'var Torah which explored the question of what it might mean that at the end of Exodus the entire community of Israel sees the fire and the cloud, together.

And then after our oneg (which featured not one but two beautiful small birthday cakes!), a handful of folks stayed to learn a Kedushat Levi text, which led us into a conversation about how when we enter into Shabbat wholly, we heal the workweek.

This Shabbat felt restorative. As a working rabbi, as a working mother, I've found that Shabbat doesn't always feel like the oasis in holy time that I want it to be. But this week I glimpsed that. I'm grateful.

March 14, 2012

Three melodies for the Order of the Seder

In honor of Pesach being just around the corner, I wanted to share a few Pesach melodies. Specifically, here are three different melodies one can use for singing the order of the seder. You probably know already that the word "seder" means order, from the Hebrew לסדר / l'sader, "to arrange." And there's a set order to the proceedings: fifteen steps from beginning to end.

Why fifteen? Fifteen were the steps up to the Temple, once upon a time, which were understood to correspond to 15 songs of ascent found in psalms. The Hebrew number fifteen can be spelled either as ט''ו / 9+6 or as י''ה / 10+5 -- and that latter spelling also spells "Yah," a name of God. The folks at Aish.com note that "The Sages say that Passover occurs on the 15th of Nissan (the Jewish month), to teach us that just as the moon waxes for 15 days, so too our growth must be in 15 gradual steps. Think of these as 15 pieces of the Passover puzzle." To me, the fifteen steps of the seder are like gates through which we pass on the evening's spiritual journey: from kadesh, kicking things off by reciting the kiddush and thereby sanctifying time, all the way to nirtzah, the seder's conclusion.

In recent years I've borrowed a custom I learned from Hazzan Jack Kessler and Rabbi Marcia Prager at the seder they led at Elat Chayyim some years ago. In my seder, as we reach each of these gates, we sing through the 15 steps (start to finish), and then sing the melody again, as far as whererever we are on the journey. So the first time we do it, we sing all fifteen steps, and then just sing the first one. The second time, it's all fifteen and then the first two. Then all fifteen and the first three. And so on. It can be hard to remember to stop singing, especially as the evening's four glasses of wine are consumed, so hilarity sometimes ensues!

Anyway, the melody I use for that practice is this one. I don't know its origin, but here you go:

The second melody I want to offer is the one I learned as a child. This is the one I used to sing at seder with my family when I was a kid. Alas, I don't know its provenance either, but I like it:

Order of the seder - from my childhood

And the third melody I have to offer is the melody for the hymn "Sanctuary." (I've shared it here before -- for a post on Brich Rachamana.) Here's how the order of the seder can be sung to that tune:

Order of the seder - to Sanctuary

If any of these melodies speak to you, please feel free to take them and use them in your seder this year. (And if you use a different melody for this part of the seder, feel free to record it and leave a link here, or point to it on YouTube if you can find it there -- I'm always interested in different ways of singing familiar words...)

March 13, 2012

Preparing for the season that's coming

Erika at Black, Gay, and Jewish mentioned in a post yesterday that there are 25 days until Pesach. 25 days! That doesn't sound like very long. Maybe this is a good time to remind y'all that if you're still searching for a haggadah, the Velveteen Rabbi's Haggadah for Pesach is available as a free download. Read all about it: Velveteen Rabbi's Haggadah for Pesach 7.2 (2012, 48 pages, abridged from last year's long version though a few improvements have been made and a few new things added) and Velveteen Rabbi's Haggadah for Pesach 7.1 (2011, 84 pages.)

People have graciously said some very kind things about my haggadah: "I was blown away by the insights and freshness that I found in your haggadah" (Tony) and "I am in the process of converting, and I have struggled to find a haggadah that reflects not only my Judaism, but my feminism and my politics. This is finally one that I can share with my family as I lead my own seder for the first time. Thank you for offering the world this method of telling the story of our freedom" (Natalie) and "I used your haggadah as my foundation for leading the second seder for my family... They told me afterwards it was the most meaningful seder they had ever attended -- actually they told me it was the FIRST meaningful seder they had ever attended" (Rhonda.) I hope that if you use it, it helps you connect with Pesach in deep and meaningful ways.

I've been putting a lot of energy lately into preparing for what comes after Pesach: the Counting of the Omer. For years I've toyed with the idea of trying to post something -- a thought, a teaching, a blessing -- relating to each day of the Omer count. Now that I'm blessed to serve as a congregational rabbi, I found my desire to make the Omer meaningful for people (maybe especially people who don't usually think in terms of counting the Omer each night during that holy seven-week span) even stronger. So I seized that desire and ran with it.

This year I'm actually going to manage it, and I'll be sharing those daily postings at the From the Rabbi blog which I maintain for my shul. The trick, I've realized, is to queue up the postings before the Omer begins, so that once we're in the Omer count, I can let each day's unique combination of divine qualities wash over me instead of fretting about whether or not I've posted anything today. I've been working on these for weeks, and they're finally complete. I'm looking forward to the first post going live, on the evening of the first full day of Pesach, as we approach sundown and prepare to begin Counting the Omer. Anyway, I'll post more about those here soon, including instructions on how to subscribe just to the Omer posts on that blog.

What else can I tell you? It's an overcast morning here, cool and grey. Purim already feels a long way distant. Pesach approaches, inexorably. Spring is on the way.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers