Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 227

April 3, 2012

Buy 70 faces during National Poetry Month!

It's National Poetry Month in the United States. And although Phoenicia, my publisher, is based in Canada, they're having a 10% off sale on all of their poetry titles during the month of April.

If you don't yet own a copy of 70 faces, my collection of Torah poems -- or if you've been meaning to buy one for a rabbi, a pastor, a friend -- this month is a great time to pick one up!

For more on 70 faces (excerpts from reviews and interviews, etc), visit the 70 faces category at the Phoenicia blog; or, from the book's page at Phoenicia, you can read excerpts, hear me read excerpts, and (hopefully) choose to purchase a copy! 70 faces is available from Phoenicia's online store, or from Amazon.

Happy poetry month to all!

April 2, 2012

Judge of beginnings, middles, and endings

In Jewish tradition, when we hear that someone has died, we say a blessing.

Sometimes, when I tell mourners this, I can see in their eyes that they are baffled, or even upset, by this custom. What can it mean to offer words of praise to God upon the occasion of a death? For most of us, in most cases, when someone has died, praise is not what comes first to our lips. And maybe that's part of our tradition's wisdom. When someone has died, we're asked to offer a blessing -- to praise God not despite our sorrow, but in and through that sorrow.

What is the blessing we recite? ברוך אתה ה', אלהינו מלך העולם, דיין האמת / Baruch atah Adonai, eloheinu melech ha-olam, dayan ha-emet, usually translated "Blessed are you, Adonai our God, ruler of the universe, the true judge." (The full blessing is said by those who have suffered the loss; the rest of us use the first word and the last two words as our response to the news. ".ברוך דיין האמת / Baruch dayan ha-emet," Blessed is the true judge.)

Whew. That can be a tough one for us to swallow. We moderns don't typically think of God as a judge; we're more comfortable with other metaphors. God as parent, God as Beloved, God as creator, wellspring, source. But Judge? We use judge and king metaphors during the Days of Awe, and often we struggle with them then. How can we relate to this metaphor in our moments of personal mourning? Perhaps especially if the death seems to us to be "unfair"?

Rabbi Marcia Prager teaches that one answer can be found in the very letters of the blessing -- specifically the Hebrew word אמת / emet, truth. The letters of the Hebrew word for "truth" are aleph, mem, and taf -- the first letter of the alef-bet, the middle letter, and the last letter. What is true of every life? Every journey has a beginning, a middle, and an end.

When we read Torah each year, the ending and the beginning kiss (on Simchat Torah, when we read the very end of the scroll and immediately turn around to read the very beginning.) In the lifecycle, too, every ending opens up a new beginning: for the soul of the person who has died, and for we who remain. When we make this blessing, we bless the One Who grants each of us our stories a beginning, a middle, and an end -- or maybe the One Whose presence we strive to discern in our journeys, as they begin, during the great middle of every lifetime (no matter how long or short it may be), and as each journey comes to an end.

March 30, 2012

New poem: Shacharit in the toddler house

SHACHARIT IN THE TODDLER HOUSE

I peek as you pretend to sleep

one eye open, watching me watching.

Dry diaper, blue striped shirt.

A cup of milk, toasted bread, jam.

Does God feel this satisfaction

providing for all our needs?

You won't let me sing blessings

or psalms of praise, preferring

your Thomas & Friends cd.

You tell me to go away, testing

the limits of what tethers us, but

you know I'm right outside the door

occluded but present, loving you

even when you turn away.

This is the latest poem in a budding series. Previous poems in the series are: Early ma'ariv in the toddler house, Havdalah in the toddler house, Shabbat in the toddler house. Shacharit means morning prayer. (And ma'ariv is evening prayer, and havdalah is the brief ritual which brings Shabbat to a close.) These are poems about parenting and prayer life. About how I'm trying to maintain an awareness of Jewish sacred time, even when I'm still not able to pray substantive liturgy most of the time.

There's much more spaciousness in my life for prayer now than there was when Drew was an infant...though now there are different challenges. Now he notices when I sing, and usually demands that I stop! He pushes boundaries and tests limits all the time, in a perfectly age-appropriate way. My challenge continues to be living with what my teachers would call "prayerful consciousness" -- can I embody the prayers even when I'm not saying them? What would that look like, what would it mean?

Becoming a parent continues to impact the way I think about God. I often think about the idea of hester panim -- that God's face may be hidden from us but is always present, always (in the theology to which I ascribe) loving us. Maybe God feels about us as I feel about Drew: sometimes exasperated, but always connected; I may be hidden, but my love for him is always there.

March 29, 2012

Two mother poems in Bluepepper; thanks, Bluepepper!

I recently discovered, and subscribed to, an online poetry journal called Bluepepper. Their motto is "Poetry with bite."

On my most recent round of poetry submissions, I sent a few poems there -- part of the "mother poems" series I shared here as I wrote one each week during the first year of Drew's life. They're now part of the next manuscript I hope to see in print, which has the working title Waiting to Unfold.

To my delight, the editor liked the poems I submitted, and published two of them today: New Poetry by Rachel Barenblat. He chose to publish "Fever" and "Comforter."

"Comforter" was written around the time of Shabbat Nachamu -- the Shabbat after Tisha b'Av (our central day of communal mourning), when traditionally we read the haftarah (reading from the Prophets -- in this case, Isaiah) which begins nachamu, nachamu ami (or, in the English familiar to many us thanks to Handel, "Comfort ye, comfort ye, my people.") That poem is filled with references to the Isaiah reading, even as it's also about the experience of struggling with multiple night-wakings in the aftermath of a two-week trip.

And "Fever" arose out of the experience of Drew's first summer virus; the opening lines of that poem reference a midrash about Moses, which you can find on this Daughter of Pharaoh: Midrash and Aggadah page, in the section titled "The daughter of Pharaoh raises Moses."

Anyway: thanks, Justin, for publishing my poems!

"Without Ceasing" reprinted in Running Tide

I just received in the mail my print copy of Running Tide issue 26 (spring 2012) -- also available online: Running Tide 26 at issuu -- and am enjoying it deeply. As the inside cover notes, "Running Tide offers a voice for faith and practice, as well as critical, existential and socially engaged enquiry within the broad framework of Pureland Buddhism." I'm honored to be able to say that one of my poems, "Without Ceasing," which originally appeared in the Worship issue of Qarrtsiluni (co-edited by Fiona and Kaspa of Writing Our Way Home), is reprinted in this issue of this Buddhist journal.

What is Pureland Buddhism? Wikipedia offers an answer, though it's a bit challenging for me to parse; the main thing I take away is that the Pureland practice involves repeating the name of Amitābha Buddha. For a more personal take, I dip into the pages of the journal. Anthony Pilling writes a bit about this in his essay in this issue, which is called "Pureland, Beginners Mind." He describes moving to Malvern, beginning to practice with Fiona and Kaspa's Malvern sangha (community), and grappling with the shift from "just sitting" in silent meditation to what I take to be the more chant-based Pureland practices.

(By the by, if you want to know more about Pureland Buddhism, I recommend the What is Pureland? page on the Malvern sangha's website -- clear, comprehensible, and lovely.) Kaspa notes in his Editorial introduction that my poem reminds him of the Pureland practice of calling to Amida. I'm delighted by this area of overlap between my spiritual tradition and his.

There's much in this issue which intrigues and moves me. Gregg Krech's essay "Relationship as Spiritual Practice" offers insights into how, when one relinquishes the desire to control or "fix" one's partner, one can relax into a more loving paradigm of relationship. And in "Endings," Caroline Screen meditates on leaving Australia after twelve years and on the very human temptation to soften a goodbye into "see you soon" -- whether it's the goodbye of leaving a place where you have lived, or the goodbye of burying a loved one.

Thank you for reprinting the poem, Kaspa! And thank you for introducing me to this journal and to this glimpse of a different set of practices and ideas, both similar to and different from my own.

March 28, 2012

Short review of Beloved on the Earth: 150 poems of grief & gratitude

As a rabbi and as a poet, I commend to all of you the collection Beloved on the earth: 150 poems of grief and gratitude, edited by Jim Perlman, Deborah Cooper, Mara Hart and Pamela Mittlefehldt and published by Holy Cow! Press. As the editors write in their preface:

We turn to poems for solace, wisdom, comfort, joy. We wrap ourselves in words -- words of mourning and grief, words of mystery, words of gratitude and remembrance. As unique as each life is, so is each death. And yet, in our isolated grief and mourning, we turn to the comfort, the embrace of the words of others.

Indeed yes.

Some of the poems in this book were known to me before I picked up this anthology -- Jane Kenyon's Let Evening Come (which I just last week resolved to bring to the next shiva minyan I lead), Kay Ryan's Things Shouldn't Be So Hard. And many were unknown to me. All of them move me.

Sheila Golburgh Johnson's concrete poem "Yahrzeit" takes the shape of a flickering memorial candle flame. Maxine Kumin's How it is offers up the experience of wearing the blue jacket of an old friend, now gone. Jane Ellen Glasser's "Sharing Grief" opens the experience of two people comparing grief over the phone, "the forms it takes / in the foreign countries / inside us." With its images of unfilled jars and absence, Natasha Trethewy's After Your Death opens the gaping chasm of emptiness.

Here are two of my favorite poems from the collection, or at least, two of the poems which speak most to me today. This one, which opens the collection:

Late Fragment

Raymond Carver

And did you get what

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

I love the way the Carver poem feels like a shred of conversation, something we enter in medias res, already unfolding. And what more do any of us yearn for than to be beloved?

And this one, with its echoes of Dylan Thomas:

Go Gentle

Linda Pastan

You have grown wings of pain

and flap around the bed like a wounded gull

calling for water, calling for tea, for grapes

whose skin you cannot penetrate.

Remember when you taught me

how to swim? Let go, you said,

the lake will hold you up.

I long to say, Father let go

and death will hold you up.

Outside the fall goes on without us.

How easily the leaves give in,

I hear them on the last breath of wind,

passing this disappearing place.

Pastan gives voice here to the complicated longing of watching a parent die. And the poem's final images read both as autumnal description and as a wish for what's coming. If only we could let ourselves go as easily as do the falling leaves -- or, in the Talmud's preferred imagery, as gently as a hair lifted out of a bowl of milk. The "last breath of wind" makes me think of the neshama, the soul-breath which enlivens us; the disappearing place is this life which we enter and then leave.

As a clergyperson and pastoral caregiver, and also as a poet and reader of poetry, I am so glad to have this book at hand. My thanks are due to the editors of this collection, for assembling something so poignant and beautiful and profound.

March 27, 2012

Two texts before Pesach: a Rumi poem, and a Reb Nosson teaching

Remember the amazing Rumi morning service I attended back in January? I've been beginning to work recently on adapting the liturgy from that service for use at my shul, and am planning a Rumi Shabbat on May 5, about which more anon. Anyway, one of the poems we'll probably use in our Rumi Shabbat service is this one, which draws on the Qur'anic (and Torah) story of Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt. I wanted to share it here in advance of Pesach, which is coming soon!

This poem reminds me of a Hasidic teaching about the Exodus from Egypt, which I will also share below. First, here's the Rumi poem:

Remember Egypt

You that worry with travel plans,

read again the place in the Qur'an

where Moses is taking the Jewish

nation out of slavery. You so

frantic to have more money, recall

what they abandoned to wander in

the wilderness. You who feel hurt,

remember the pavilions and houses

left behind. You that lead the

community through difficulties, read

about the abundant fountains they

walked away from to have freedom.

You who dress in clothes that appear

to have elegant meaning, you with so

much charm, remember how your face

will decay to dirt. You with lots of

property, "They left their gardens

and the quietly running streams."

You who smile at funerals going by,

you that love language, measure wind

in stanzas and recall the exodus,

the wandering forty-year sacrifice.

(Edited to add: this is a translation by Coleman Barks, and can be found in The Soul of Rumi -- online here via googlebooks.)

And here's the Hasidic teaching. This is commonly attributed to Reb Nachman of Bratzlav, though my teacher Reb Elliot taught that this actually comes to us via Reb Nosson, Reb Nachman's disciple/amanuensis. Reb Nosson wrote:

One needs to leave Mitzrayim ("The Narrow Place," e.g. Egypt) with great haste. This is the essence of "for they left Mitzrayim and couldn't tarry, and also they didn't make provisions [for the journey]." (Exodus 12:39) This is found in each person and in each era. Each person in each time, in experiencing the cravings and the woes of this world, experiences the essence of the exile in Mitzrayim...

And here is the essence of Pesach. At the time of the Exodus from Mitzrayim, a great light from on high was revealed; and at that time, promptly and in a jiffy Israel went out in great haste. They couldn't tarry, for even if they had remained there even one more instant, they would have remained a remnant there. It's forbidden, in the moment of exodus, to worry about parnassah [income], to worry "But if I do this, how will I make a living?" Rather one must trust in God and hope in the Blessed One, and God will provide.

This is the essence of "And also they didn't make provisions." [That's the end of that same Exodus quote from before.] If one needs to flee from, e.g., being trapped in a snare, one wouldn't think of parnassah and preparations, for certainly thieves and robbers would fall upon one, or wild beasts, and one would need to speedily free oneself from them; certainly there would be no thought then of how one would make a living. The same is true if a person needs to flee from She'ol around and beneath him, or from the tribulations of the world toward the life of this world [e.g. God]. One would need to flee speedily and not look behind oneself at all; for one must not tarry, nor worry about preparations, but trust in God and rely on God, who will never leave one.

What I hear Reb Nosson saying is that when it's time to leave the Narrow Place, one has to do it speedily, without getting caught up in anxiety about how the logistics are going to work. There's a certain kind of leap of faith involved. Just as one would flee quickly from a literal trap, so we should aim to flee from the spiritual traps which would otherwise keep us constricted. This isn't merely a teaching about what happened to them then; it's also about what happens to us now.

What I hear Rumi saying is that all of us who become consumed with thoughts of logistics and possessions need to remember the Exodus from Egypt, remember how the Israelites left that place with their hastily-improvised flatbread. When we can bear the Exodus in mind -- when we can, as the haggadah teaches, see ourselves as though we ourselves had been brought forth from Mitzrayim, out of the house of bondage -- then we will hear the poetry in the very wind, and maybe find the freedom in the wind, too.

May your journey toward Pesach be meaningful and sweet!

March 26, 2012

New poem: Shabbat in the toddler house

Drew and mama on a Friday night.

You bound toward my car

windbreaker clutched in one hand

hair spiky with sunscreen

by the time we reach the bakery

you're vibrating

on the sidewalk you shout for joy

soon you have half a cookie

in each fist, chocolate chips

already smearing your face

we watch the challah

exit the oven, so hot

I won't let you touch it

when I try to sing the blessings

you yell "mommy, stop!"

because it's not the alphabet song

all you eat for dinner

are tufts of fresh bread

but I don't mind

Shabbat means sweetness

even if you don't understand

work or time

or the angels I see peering

through our windows

blessing us that next week

should be just like this one

as you chug watered grape juice

and the tealights gleam

This poem is part of a small but growing series, which includes Early maariv in the toddler house and Havdalah in the toddler house.

March 25, 2012

Resources for Counting the Omer

Pesach is on its way! The first seder will be on Friday, April 6 -- less than two weeks away. And on the second night of Pesach, we begin the process of Counting the Omer, counting each of the 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot, between the festival of our freedom and the celebration of the revelation of Torah at Sinai, between liberation and covenant.

During the Omer count, I'll be posting a series of daily Omer teachings on the CBI From the Rabbi blog, which I hope will help enrich and sanctify this special corridor in time. (If you use a blog aggregator or feed reader, you can subscribe to the Omer postings at this feed URL; alternatively, you can choose to receive emails when posts appear on the From the Rabbi blog -- just head over there and click on the "sign me up" button under "Follow blog by email.") But if you'd like some resources for Counting the Omer on your own, here are four of my favorites. Three are newly-published books, and the fourth came out in 2010.

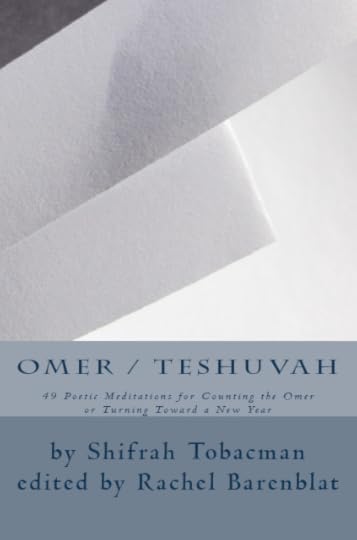

Omer / Teshuvah: 49 Poetic Meditations for Counting the Omer or Turning Toward a New Year

by Shifrah Tobacman, edited by Rachel Barenblat

This collection of poems by Shifrah Tobacman offers meditations for each of the 49 days of the Omer count, from Pesach to Shavuot, from freedom to revelation. These poems will open your heart and your spirit as you move through the gates of each day. And the book is also designed to be read in the other direction (like a Hebrew book, right to left) during the Omer Teshuvah, the 49 days between Tisha b'Av and Rosh Hashanah.

The collection is edited by Rabbi Rachel Barenblat, author of 70 faces: Torah poems (Phoenicia publishing, 2011) and features photography by Elizheva Hurvich.

Omer Calendar of Biblical Women

by Rabbi Jill Hammer with Shir Yaakov Feit

The Omer Calendar of Biblical Women is a journey through the seven weeks between Passover and Shavuot. According to the Kabbalah, each of these forty-nine days embodies a unique combination of Divine attributes, or sefirot. Each day of this calendar features the story of a biblical woman who embodies the unique spiritual dimension of that day of the Omer. The calendar also contains illustrations from classical paintings and modern midrashic art.

The author of the calendar is Rabbi Jill Hammer, PhD, author of Sisters at Sinai: New Tales of Biblical Women and The Jewish Book of Days: A Companion for All Seasons. Rabbi Hammer is Director of Spiritual Education at the Academy for Jewish Religion. Shir Yaakov Feit, Creative and Music Director of Romemu, New York City's Center of Judaism for Body, Mind, and Spirit, designed the calendar.

By Rabbi Yael Levy

In this book, Rabbi Yael Levy gathers wisdom from Psalms and the Jewish mystical tradition into a unique Mindfulness approach to the ancient Jewish practice of Counting the Omer during the 49 days between Passover and Shavuot.

This 96-page, full-color guide includes the Omer blessings in Hebrew and English, daily teachings and intentions, pages for reflections and photographs to inspire meditation. Daily suggestions for action deepen the experience of counting each day and making each day count.

Using insights gained from more than a decade of her own spiritual exploration with the Omer, Rabbi Levy has created a guide for spiritual growth for beginners and those who have experience with this practice.

Rabbi Yael Levy's Approach to mindfulness is deeply rooted in Jewish tradition. She is the founder of A Way In, A Jewish Mindfulness program based in Philadelphia that offers a range of activities from meditation and contemplative Shabbat services, classes and retreats, as well as online teachings and practice. She is a spiritual director for rabbinical students in both the Reconstructionist and Reform movements as well as in private practice.

Her Mindfulness teaching grows out of her deep personal commitment to spiritual practice and a passionate belief in its potential to change not only individuals but the world.

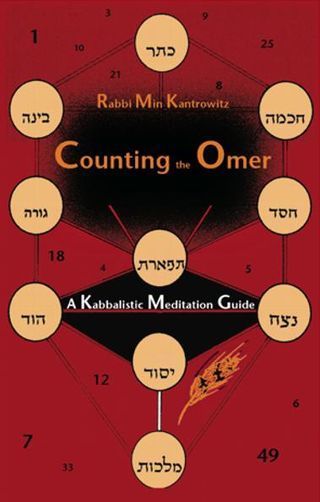

Counting the Omer: A Kabbalistic Meditation Guide

by Rabbi Min Kantrowitz

Counting the Omer is a Kabbalistic meditation guide to understand the in-depth meanings of each of the forty-nine days between Pesach (Passover) and the Shavuot celebration of the revealing of the Torah. Rabbi Kantrowitz follows Kabbalistic guidelines to show how the unique values of the sephirot interact each day, giving the reader insight into the strengths of the day. Through this guide the reader is led to meditate on the mystical qualities of life and self.

Rabbi Min Kantrowitz is the Director of the Jewish Community Chaplaincy Program of Jewish Family Service of New Mexico, which provides spiritual support and pastoral care services to thousands of unaffiliated Jews. Rabbi Kantrowitz also directs the Albuquerque Community Chevre Kaddisha, facilitates grief support groups and conducts Healing Groups for Jewish survivors of domestic abuse. She is a sought after speaker and teacher, having conducted services, workshops and lectures in Europe, California, Montana, Arizona, and across New Mexico. She received her Rabbinic Ordination in May 2004 from the Academy of Jewish Religion in Los Angeles. In addition, she holds a Bachelors Degree in Psychology and Masters Degrees in Psychology, Architecture, and Rabbinic Studies, as well as a Masters of Science in Jewish Studies.

And, if visual art speaks to you more than does text, try D'vorah Horn's Omer Series of paintings, available on beautiful printed cards for $36.

Happy counting!

(This is cross-posted to the CBI From the Rabbi blog -- if you're reading both, you'll get it twice; sorry about that!)

March 23, 2012

Announcing Shifrah Tobacman's collection of Omer poems

It gives me great pleasure to be able to announce the publication of Omer/Teshuvah, a collection of daily Omer poems written by my friend and rabbinic school colleague Shifrah Tobacman, published under the auspices of Omeremo Nanopress.

These are meditative reflections intended to enrich one's experience of counting the Omer, marking the 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot, between liberation and revelation. And -- here's the really cool part -- they're also intended to be used during the 49 days between Tisha b'Av and Rosh Hashanah, a seven-week journey Shifrah calls the Omer Teshuvah. If you read the book like an English book, it's an Omer book; if you read it like a Hebrew book, the poems lead you through the Omer Teshuvah.

At the book's website you can learn more about our collaboration, read Shifrah's introduction and the introduction I wrote as the collection's editor, see what others have to say about the collection, read an excerpt -- and then, hopefully, buy yourself a copy which will be printed and bound and shipped to you in time for the Counting of the Omer, which this year begins on the 7th of April. Click on through: Omer/Teshuvah. (And/or go directly to CreateSpace to purchase a copy.)

This project has taken up a fair amount of my creative time and energy this winter, and I'm delighted to be midwifing it into the world as Passover approaches! It's a blessing for me to be able to help facilitate the emergence of a new Jewish Renewal devotional poetry voice. (And yes, editing this collection and preparing it for print gives me all the more admiration for my friends and colleagues for whom small-press publishing is an avocation.)

My deep thanks are due to Shifrah for letting me play a role in this process; I hope y'all enjoy her poems, as I do.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers