Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 216

August 4, 2012

We find God when we bring comfort: a d'var Torah for Shabbat Nachamu

Here's the d'var Torah I offered this morning at my shul.

נַחֲמוּ נַחֲמוּ עַמִּי יֹאמַר אֱלֹהֵיכֶם -- Nachamu, nachamu ami, yomer eloheichem.

"Comfort, comfort My people, says your God."

Today is Shabbat Nachamu, named after the first word of today's haftarah portion, Isaiah 40:1-26. Nachamu is in the plural; it means "y'all offer comfort." Or, in the locution you might recognize from Handel, "Comfort ye, comfort ye my people."

Last weekend brought Tisha b'Av, when we immerse deep in the realities of human suffering and the brokenness of our world. The fall of the first Temple, and our people becoming refugees in Babylon. The fall of the second Temple, which must have been even more heartbreaking than the first. And a dozen other tragedies and traumas throughout our history.

For some of us, Tisha b'Av is a time to remember the suffering of the Jewish people. For others, it offers a more generalized occasion for mourning: the starvation and cruelty and rape described in Lamentations sounds like every war in history, from the Rwandan genocide to what's happening now in Syria. For still others, Tisha b'Av is a time to mourn the suffering of our planet, which burns and suffers poisons when humanity chooses progress over sustainability.

Today we take a deep breath and let go of all of that sorrow. Today is Shabbat Nachamu, the Shabbat when we are instructed to bring comfort.

There are seven Shabbatot between Tisha b'Av and Rosh Hashanah. These are called, in our tradition, the Seven Weeks of Consolation. Having delved into the depths of human trauma and suffering on Tisha b'Av, now we are called to draw on what we learned there in order to propel us in teshuvah, repentance, re/turn, turning-toward-God.

As Rabbi Alan Lew writes, spiritual practice doesn't remove what hurts in the world. It doesn't take away our suffering, whether personal or national, chronic illness or the fall of the Twin Towers or death which comes too soon. But spiritual practice can allow us to see what happens more clearly, and to respond to it with compassion and with love.

One of my role models in this is a Unitarian minister named Kate Braestrup. Kate is author of a number of terrific books, including Here If You Need Me, in which she tells the story of how her husband Drew, a Maine State Trooper, was killed in a car accident, leaving Kate widowed with four young children. Here is a quote from that book, which I have returned to many times.

My children asked me, "Why did Dad die?"

I told them, "It was an accident. There are small accidents, like knocking over your milk at the dinner table. And there are large accidents, like the one your Dad was in. No one meant it to happen. It just happened. And his body was too badly damaged in the accident for his soul to stay in it any more, and so he died.

God does not spill milk. God did not bash the truck into your father's car. Nowhere in scripture does it say, 'God is car accident,' or 'God is death.' God is justice and kindess, mercy, and always - always - love. So if you want to know where God is in this or in anything, look for love."

Where do we find God when there is tragedy? For Reverend Braestrup, God is in the loving hands which prepare a casserole and deliver it to your door when something unimaginable has happened; God is in the loving arms which hold you as you weep.

Let me expand on that a little bit.

God is in the friend who offers to hold a newborn so its exhausted mother can take a shower and get some sleep. God is in those who gather for shiva so the mourner can say kaddish in the presence of a minyan. God is in the friend who makes a pasta salad and brings it to the home of a woman whose husband has slipped a disc and can't get out of bed. God is in the parent who rocks a croupy child in a steamy bathroom in the middle of the night. We find God in our acts of love for one another.

When you listen to someone pour out their worries, you are God's ears, listening. When you place a hand on someone's shoulderblade, or offer an embrace, you are God's hands, soothing. When you make meatloaf for Take and Eat, your hands are God's hands, providing sustenance. And when you offer comfort, you are God's presence, comforting.

This is how I understand נַחֲמוּ נַחֲמוּ עַמִּי יֹאמַר אֱלֹהֵיכֶם -- Nachamu, nachamu ami, yomer eloheichem. "Y'all comfort -- really comfort -- My people, says Your God." It's our job to comfort one another. And when we do, we bring God's presence into the world and into our lives.

August 3, 2012

A Prayer for Syria

Shekhinah, in Whose womb creation is nurtured:

when your children are slaughtered you weep.

Bring peace beneath Your fierce embrace

to Syria. Let a new image of the world be born

in which American Jews pray for Syrians, who pray

for Israelis, who pray for Palestinians, who pray

even for American Jews. Fill the hearts

of the insurgents with Your compassion

so that when the regime comes to its end

no one seeks the harsh justice of retaliation.

And for us: strengthen our resolve not to turn away.

We bless You, Source of Mercy. Bring wholeness

to this broken creation. And let us say: Amen.

The idea that poetry can create a "new image of the world" comes from Syrian poet Ali Ahmed Said, who writes under the pen name Adonis.

If this prayer speaks to you, feel free to share it widely. I ask only that you keep my name and URL attached so that people know where it came from.

August 2, 2012

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Rosh Hashanah Sermon

I

Among twenty finished projects

The only moving thing

Was the sermon I need to write.

II

I was of three minds,

Like a desk

On which there are three sermons.

III

The sermon whirled in the summer sun

like my son's paper pinwheel.

IV

God and the Torah

are one.

God and the Torah and a sermon

Are one.

V

I do not know which to prefer,

Preaching about Syria

Or preaching about the election.

The sermon unfolding

Or just after.

VI

I searched the willow

Outside the sanctuary window.

The shadow of the sermon

Crossed it, to and fro.

The mood

Traced in the sermon

Solemn and full of joy.

VII

O congregants,

Why do you imagine lunch?

Do you not see how the sermon

Is a golden banquet

For your souls to feast on?

VIII

I know noble prayers

And lucid, inescapable rhythms;

But I know, too,

That the sermon is involved

In what I know.

IX

When the sermon flew out of sight,

It reached the edge

Of the highest heavens.

X

At the sight of sermons

Gleaming with insight

Even the sages of the Talmud

Would cry out sharply.

XI

She rode through Williamstown

In a blue Toyota.

Once, a fear pierced her

In that she mistook

A Calvino pastiche idea

For a sermon.

XII

The river is moving.

The sermon must be flying.

XIII

It was Rosh Hashanah all summer.

We were making teshuvah

And we were going to make teshuvah.

The sermon sat

Just out of reach.

With thanks to Wallace Stevens, upon whose poem 13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird this is based. The idea that God and the Torah are One comes from the Zohar. Teshuvah is the Hebrew word usually translated as repentance; I like to translate it as return or as turning-toward-God.

July 30, 2012

Now and later: beginning to approach the Days of Awe

I've had three long Skype dates recently with my friend and colleague David Curiel. David is an ALEPHnik who will be leading services alongside me during the Days of Awe. So far we've worked our way through planning services for both days of Rosh Hashanah, plus Kol Nidre, plus about half of Yom Kippur morning. (Our next call is scheduled for a few days from now.)

Each time we connect via Skype, we go through the machzor page by page: okay, this prayer, what do we want to do for this one? How about, you sing the first paragraph, I'll read the second paragraph, you sing the closing line. Or: I'll lead this one with guitar. Or: this one's all you. And so on, and so on. Slowly but surely my machzor is filling up with sticky tabs and pencil markings.

As a result my mind is overrun with high holiday melodies. The nusach, the specific melodic modes unique to these days. The individual melodies we'll be using for this prayer or that one. The niggun (wordless Hasidic melody) I want to use a few times during the service. Shir Yaakov's new setting for Rabbi Rami Shapiro's We Are Loved, which we're planning to teach.

And yet we're barely past Tisha b'Av. I still don't know what my Rosh Hashanah sermon is going to be about. It's peach season, corn season, the season of crickets and cicadas singing their rising-and-falling summertime song.

So many competing impulses at this moment in the year. I want August to last forever: so I can splash with Drew at Margaret Lindley pond, so we can eat ice pops on the deck after dinner, so I can revel in the harvest gloriousness of the Berkshires at this time of year. Corn and peaches and basil. The rustle of the deep green leaves. And yet I'm looking forward, anticipating what's next. Like a kid who's too restless to sleep, knowing that school starts soon. Excited and reluctant.

So many competing responses at this time of the year. I'm eager for the Days of Awe, for the sounds of the season, the taste of challah drizzled with honey, my parents' annual visit, the introspection of the teshuvah process. I'm anxious about the Days of Awe: so many people come to shul then who don't come at any other time of year! What if we don't give them what they need? Is there anything we could do to make them want to come back, to immerse more frequently in these waters?

There's always the reminder that my own teshuvah work needs to be paramount. If I don't do the discernment of figuring out where I'm missing the mark, then I miss the opportunity to do better -- to be better -- in the year to come. And yet it can be hard to make the space for my own teshuvah when that little voice in the back of my head keeps reminding me that I still don't have the perfect idea for that Rosh Hashanah sermon.

And through all of it, maybe the real challenge is balancing the need to make lists and plan and anticipate the future with the ability to be in this moment. End of July. This beautiful sunny day. This cuddle with my child, this blog post, this instant. This opportunity to be who I yearn to be, right here, right now.

July 28, 2012

A poem in Adanna, issue 2

I'm delighted to be able to announce that one of my mother poems -- "Weaning" -- has been published in issue 2 of Adanna, "A Journal for Women, about Women." Here's how editor Christine Redman-Waldeyer explains the name:

Adanna, a name of Nigerian origin, pronounced a-DAN-a, is defined as “her father’s daughter.” This literary journal is titled Adanna because women over the centuries have been defined by men in politics, through marriage, and, most importantly, by the men who fathered them. Today women are still bound by complex roles in society, often needing to wear more than one hat or sacrifice one role so another may flourish.

My poem appears alongside many others which I quite like, by poets I know and admire -- Margo Berdeshevsky, Kristin Berkey-Abbott, Elliot batTzedek -- as well as poets who are new to me: Cathy Carlisi, Barbara Crooker, Suzanna Dalzell, , Kristin LaTour, Marvin Shackelford, Carole Stone, Pramila Venkateswaran.

There are some haunting juxtapositions of image and theme here -- nursing, from my poem "Weaning" to Carlisi's "Milk Made;" miscarriage, from Dalzell's "North Dakota" to Foley's "Small Ceremonies." Feeding one another. Sickness and mortality. Loss. Memory. Joy. These are some of the big universals of human experience, evoked with carefully-chosen words.

I recommend this issue of this journal highly. You can buy a copy, or donate to the magazine, at their Purchase page. Thanks for including my poem, Christine!

July 27, 2012

New Torah poem - inspired by the book of Ezra

CONSTRUCTION

It's a hot day in Jerusalem.

Workmen wipe sweat, straining

to lift limestone into place.

A brass band: priests in white linen

playing polished trumpets,

Levites smashing cymbals in praise.

Old men weep who remember

when the rubble was whole

and teenagers scream for joy.

They don't know

that jealousy will stop

their construction in its tracks

that some unpaid scribe

will need to hunt the stacks

for a memorandum of permission

that this house too will fall

and the people will scatter

like cornmeal on a baking stone.

Today they celebrate: God

is on our side! No one imagines

how much harder their story will get.

This poem arises out of the story of the rebuilding of the Temple, found in the book of Ezra, chapter 3 through chapter 6.

There's something very poignant for me about imagining the rebuilding of the Temple after the years of the Babylonian Exile. Those who remembered the first Temple must have been overwhelmed with joy to see their dreams take shape again.

From the vantage point of where we are now, it's easy to think of the two temples as almost a unit. There was a Temple in Jerusalem, and it was built twice, and then it fell, and Judaism has never been the same. But there was a moment in time when the second one was built, and no one knew it was going to fall just like the first one did.

For all that I cherish the shapes and forms of rabbinic Judaism (and I do!) -- and could not imagine returning to sacrificing animals on a stone altar again -- I can imagine how crushing it must have been when the House of God was toppled.

Thinking about the story of this rebuilding, I find myself holding my breath.

Tisha b'Av, the day when we remember the fall of both temples, falls this weekend and will be observed starting on Saturday night.

July 26, 2012

An unusual wedding

The state forest arises out of nowhere. The countryside around it is quite built-up, highways and office parks and car dealerships, but then the road enters a new town, and the trees grow thicker, and suddenly there's an entryway to a state forest. I drive in and up and around to the picnic pavillion at the end of the road.

A handful of actors and a musician are moving picnic tables to create the sacred space in which the ceremony will take place. We ponder which direction the sun will be coming from on the morning of the wedding, check weather forecasts on our phones, decide to set things up beneath the pavilion instead of in the field. We practice with the chuppah. I talk through the ceremony: this, then that, then a musical number, then another reading, then this next part...

In some ways this is one of the most informal weddings I've ever done. The brides will simply walk from the campfire circle to the chuppah once everyone is seated; there will be little pomp or circumstance. In other ways, this is among the most complex. There will be guerrilla theatre, performed by a group of friends who do this routinely at weddings in their circle. The brides don't know what exactly they will do, nor when they will do it, but they know an interruption is coming. Every time I think about it, it makes me smile.

Friends who are musicians will provide processional and recessional music, plus three musical numbers during the ceremony itself. In the late afternoon light, as we relax at the picnic tables after our very laissez-faire rehearsal, groups of singers gather with guitar and portable keyboard to practice the music. Even though they start and stop a few times, and they're still working out the details of how their voices will play off of one another, it is surprisingly glorious. I wonder what it will be like when they are singing for the hushed and anticipatory crowd.

In traditional circles where the Three Weeks are considered a period of mourning, weddings are not performed during this time. In Reform circles, as this Ask the Reform Rabbi column notes, some rabbis abstain from weddings at this time, but others don't. I've come to think of the Three Weeks as a time when we are particularly attuned to suffering, and a time for discernment and teshuvah, but for me this isn't a period of mourning per se. I grieve for what is broken, but I also recognize that without the Temple's fall, rabbinic Judaism might never have arisen.

I find that I'm happy to be doing a wedding during this first week of Av. There's been so much sorrow already during these Three Weeks -- the bus bombing which killed Israeli tourists in Bulgaria, the shooting at the movie theatre in Aurora, various personal sorrows among people I know and love -- that this feels like an antidote, a tikkun: a healing. When I sing "soon may we hear, in the cities of Judah and the streets of Jerusalem, the voice of joy and the voice of cheer, the voices of beloveds rejoicing in one another" it will be an extra-fervent prayer this year.

May our sorrow turn to joy, speedily and soon.

July 25, 2012

On bathrooms, blessings, and a learning experience

About a year ago, I printed out the following on a flyer and posted it inside the stalls of the bathrooms at my shul:

Asher Yatzar / Blessing for the Body

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה' אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם אֲשֶׁר יָצַר אֶת הָאָדָם בְּחָכְמָה וּבָרָא בוֹ נְקָבִים נְקָבִים חֲלוּלִים חֲלוּלִים. גָּלוּי וְיָדוּעַ לִפְנֵי כִסֵּא כְבוֹדֶךָ שֶׁאִם יִפָּתֵחַ אֶחָד מֵהֶם אוֹ יִסָּתֵם אֶחָד מֵהֶם אִי אֶפְשַׁר לְהִתְקַיֵּם וְלַעֲמוֹד לְפָנֶיךָ.בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה' רוֹפֵא כָל בָּשָׂר וּמַפְלִיא לַעֲשֹוֹת.

Blessed are You, Adonai, source of all being,

who formed the human body with wisdom

and created within us various openings and closings.

It is known before Your throne of glory

that if one of these were to be open where it should be closed,

or closed where it should be opened,

we would not be able to stand before You and offer praise.

Blessed are You, Adonai,

healer of all flesh and worker of miracles!This blessing, which teaches us to notice and appreciate the marvel of a human body which works, is traditionally recited upon going to the bathroom. (It originates in Talmud.)

I was inspired by the memory of the old Elat Chayyim Jewish retreat center in Accord, where I first encountered this blessing ten years ago. It was posted on a laminated sign outside the bathroom door as a reminder to be mindful of the miracle of having a body which works. (The sign wasn't exactly this one, but it was similar. Nor was it as lovely as this all-Hebrew one crafted by soferet Jen Taylor Friedman, but it was the same general idea.) I didn't grow up with this blessing, but when I first encountered it as an adult, I loved it. What an amazing set of intentions for noticing and recognizing an everyday miracle.

In more recent years I've developed a special relationship with this blessing. During my pregnancy with Drew, I needed to give myself an injection of blood thinner in my belly every day. I fear needles, so this was a major hurdle for me. I got myself through it by reciting this blessing as I pushed the plunger home. The injection kept my blood flowing smoothly and prevented another stroke; the blessing kept me able to make the injections. Anyway: the blessing has become a part of my daily spiritual practice, and I wanted to offer it to my shul. We often recite this blessing near the beginning of morning services -- but most of our members do not come to services frequently, and those who do are often not there at the very beginning. So I posted it in the bathrooms.

Over the months after I posted the blessing I received a lot of feedback, mostly positive. Several people came to me and said: what is that, where is it from, it's beautiful! Some asked me to email it to them so they could have a copy at home. Some visitors asked if they could take a copy home to their own shuls. People said that it had sparked new awareness in them -- both of the miracles of their own bodies, and also of the reality that Judaism contains a way of sanctifying even this most earthy of acts.

I also heard from a couple of people who found the posted blessing troubling. God's name, they argued, shouldn't appear in such a room. From a traditional halakhic perspective, that is correct, and when these members raised this issue I did some renewed learning about it. At that time, I decided that that since many (perhaps most) of our members do not understand themselves to be bound by halakha, the consciousness-raising upsides of the posted blessing outweighed the halakhic prohibition. And then a few weeks ago, the newly-revitalized religious practices committee asked me to take the blessing down.

Hearing this instruction from the committee felt different, to me, than hearing qualms articulated by a couple of individual members. I took the blessing down immediately, and I apologized to them for having created a situation in which members of that committee felt uncomfortable. Instead I posted the bracha outside the bathroom door, for those who might still want to recite it after using the facilities but might not know it by heart, and inside the stalls I posted one of my own poems which touches on the same themes as the blessing. Here's the poem:

Blessed is the breath of life

who formed and animates this body,

its myriad organs and tissues,

protrusions, bones, and sinews;

winter skin so dry my calves rub bloody,

flesh flushed with rhythm and heat;

curve of hip distinguishing me

from my mother whose pants need belting;

nailbeds a reincarnation

of my grandmother's long fingers;

tiny dunes of bicep I have labored

to bring into being and maintain;

narrow feet which fit snug

only in the most expensive of shoes;

wrists and ankles I can encircle

with thumb and forefinger;

nose and mouth that together savor

venison, real vanilla, green tea;

hair so limp and fine I could still use

Johnson & Johnson's baby shampoo;

all the weird, wet, noisy orifices

I need daily but can’t understand.

If my bowels were to fail, or my pancreas,

my vision...? Doctors would stitch and sew,

but it wouldn't be easy

and You'd still have to prop me up

as You do today and every day.

Blessed are You, creator of embodied miracles.

Beneath the poem I included text indicating that anyone who wanted to offer the traditional blessing would find it posted outside the bathroom door. (This poem, in a slightly earlier revision, was first published in Zeek magazine and also appears in Jay Michaelson's book God In Your Body: Kabbalah, Mindfulness, and Embodied Spiritual Practice.)

The poem, too, seemed to resonate with people. I heard some kind words about it, most meaningfully (for me) from a Jewish poet who visited our shul. And then the committee met again, and asked me to remove the poem as well. I apologized to them a second time; the poem is now gone from the walls, too.

I'm glad I posted the blessing, and then the poem; and I'm glad that the religious practices committee was able to articulate their needs so that I could fulfill them by taking the blessing and the poem down. Both of these are, I think, good things. And the whole adventure has given me opportunities for reflection about one of the interesting challenges of serving a religiously-diverse smalltown liberal Jewish congregation.

The people who found the blessing, and then the poem, inappropriate are people who come from a relatively traditional background. They know this blessing, and have probably known it since childhood. They know the halakha which says that one can recite Modeh/Modah Ani in the morning before washing hands, but that ritual handwashing is required before reciting the rest of the blessings of morning prayer, including this one. And they feel a deep and visceral discomfort with having any kind of prayer, or even prayer-like poetry, in a bathroom. For them, the halakhic prohibition is the end of the story.

The people who found the blessing, and then the poem, uplifting are people who come from a less traditional, and/or less-observant, background. Some of them are Jews by choice; some of them are strongly identified Reform; some of them have returned to Judaism as adults but didn't necessarily receive much Jewish education as kids. They largely didn't know the blessing before it was posted, and encountering it was meaningful for them. Halakha is by-and-large not part of their worldview or their Jewish practice. Their relationship with Judaism and with prayer is primarily one of choice and of what speaks to their souls, rather than what generations of rabbis and teachers have legislated.

I have empathy for both of these positions. And I think the tension between them can be fruitful and healthy -- and I suspect it exists in a lot of small congregations. (Probably big ones, too.)

There's no question in my mind that this was a worthwhile experiment -- and also that taking the blessing, and then the poem, down was the right thing to do. But I think there's an interesting question beneath all of this: what are the best ways to balance the needs of people in a community who have different relationships to halakha and different priorities in their religious lives?

Does the reality that our shul is affiliated Reform, and the Reform movement has historically privileged informed choice over halakha, make a difference? Does the reality that our shul includes members whose backgrounds are Orthodox and Conservative, in addition to members who are strongly Reform-identified, make a difference? How about the reality that we are the only shul in town? (There are others within a reasonable drive -- 45 minutes in either direction -- but we are the only shul in Northern Berkshire county.)

I don't actually have answers. But I'm grateful to have had this opportunity to think more about the questions.

July 24, 2012

As Tisha b'Av approaches

We begin our descent

toward the rubble.

Our hearts crack open

and sorrow comes flooding in.

Help us to believe

that tears can transform,

that redemption is possible.

The walls will come down:

open our eyes, give us strength

not to look away.

July 23, 2012

A prayer from Reb Zalman for Tisha b'Av

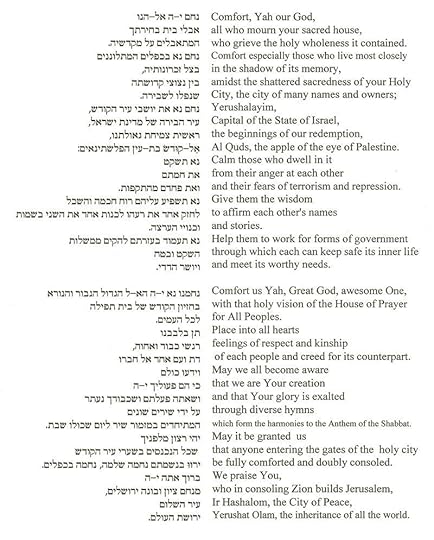

Here's a prayer for Tisha b'Av, written by Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, a.k.a. Reb Zalman.

This comes from the Reb Zalman Legacy Project blog; in this post he explains the origin of this prayer. It's meant to be recited on Tisha b'Av, the day when we mourn both fallen Temples, which this year begins on Saturday, July 28, at sundown. I find it both beautiful and meaningful; I hope you do too.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers