Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 219

June 29, 2012

The sweetness of the sour

A week or two ago my friend Kate gave me a gift of cultured culture. It's a North Adams sourdough, cultivated by artist Eryn Foster as part of Oh, Canada, a large scale exhibition of Canadian art at MASS MoCA. Foster "spent two weeks foraging for wild yeast all over North Adams in areas of natural, cultural and geographic significance." Then she generated this bubbly sourdough starter. Now interested museum visitors can ask for samples, and receive them in pint jars. That's what Kate brought to me. (For more on this, try Wild yeast and Care and feeding of Sourdough -- both by Kate, in the Berkshire Eagle and on the Berkshires Week blog.)

I followed the instructions which came with it: fed and watered it, let it sit overnight, marveled at its yeasty bubbly aroma, pungent and sour. Put some back into the fridge for next time. Used some to bake a few loaves of bread -- my first sourdough! They turned out beautiful, with a golden-brown crust, an airy crumb, and -- after an overnight rise in the fridge, followed by an all-morning proof -- a lovely gentle sour. Suddenly I was reminded that once upon a time, all leavened bread must have been sourdough.

Sourdough challah, first rise.

Of course. I should have thought of that sooner. This is, after all, a theme on which I teach each spring as Pesach approaches. The Hebrew word for something which is leavened is chametz, from the root meaning "to sour or ferment." Leavened bread involves fermentation. (Matzah does not. It's made of the same ingredients as leavened bread -- water, flour, maybe a pinch of salt -- but is made quickly enough that no leavening, no fermentation, takes place.) It is the very nature of chametz to be sour. Or it was, presumably, when the word came into use.

I used to bake bread every Friday, though these days I don't often make the time. And I've grown to love the weekly ritual of taking Drew to the A-Frame Bakery in Williamstown after daycare on Fridays, where he joyfully clamors for "a challah an' a cookie!" But I was tempted by the thought of Maggie Glazer's Sourdough Challah. I've never tasted a sourdough challah. Would the bread have any of the tang I associate with sourdough? Or would it simply be a rich challah which happens to be leavened only with the natural activity of yeast and flour and time? (For that matter: would it leaven? Or, in the absence of a packet or two of storebought yeast, would I wind up with flatbread?)

Sourdough challah, second rise.

The process was, unsurprisingly, different from the other challah doughs I've made. First I fed and wakened my starter over the course of a long day. Then I took a mere two tablespoons of starter and mixed them into a sponge and let that grow overnight. Then mixed an eggy dough and kneaded the sourdough sponge into that and let it rise all morning. Then shaped braids to proof, a.k.a. rise again. It's a slow journey, but a pleasant one. The sourdough sponge was unbelievably soft, with a texture unlike anything else I know. The braids slowly swelled, going from looking comically small on their baking sheets to looking like pale raw challot.

I realized at the last minute, oven pre-heated and ready to go, that I had used all three of our remaining eggs to make the dough. I'd meant to buy more, but had gotten distracted by other things at the grocery store, and had completely forgotten. So after a bit of googling (and after asking twitter for suggestions) I wound up glazing one in milk, the other in milk mixed with a bit of honey. It was a hot day for baking, but there is always something profoundly satisfying about the magic of turning flour and water (and sourdough starter!) into bread.

Two sourdough challot, cooling.

They didn't rise quite as much as I had hoped; I might have to let them proof longer next time. Still, the fact that I got two braids of challah out of what started life as a small ball of dough leavened with two spoonfuls of starter seems a little bit miraculous. The texture is light, and the bread has a beautiful crumb. And on the whole, the bread is sweet. There's just the lightest tang of sour at the end of a bite, just before I swallow.

They're not quite as beautiful as the one I usually get from the bakery, but the satisfaction of having made them sweetens them for me. As it happens, I had extra things to celebrate on this particular Shabbat. On the previous evening, the membership of my congregation approved my contract for two more years. A new contract, two loaves of homemade bread, and the company of loved ones on the deck at suppertime: what could be finer?

Thanks, MASS MoCA; thanks, Kate; and thanks to the Source of All Who brings forth bread from the earth.

Pekar & Waldman: Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me

Harvey Pekar was an American underground comix legend. A lot of people know him for American Splendor, a series of autobiographical comic books. He was a giant, in his own way. He died in 2010, survived by his wife Joyce Brabner.

JT Waldman is the creator of Megillat Esther, which I reviewed here several years ago. It's my favorite edition of the book of Esther, bar none. It contains -- as the saying goes -- the whole megillah; all of Esther, plus all sorts of commentary interwoven throughout the gorgeous artwork.

When Harvey Pekar died, he and JT Waldman were collaborating on a nonfiction graphic novel -- an illustrated memoir with historical divagations -- called Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me. The book follows the two authors through Cleveland as they discuss Pekar's relationship with Israel, from the Zionism he imbibed in childhood through a process of beginning to question Israel's role in the world.

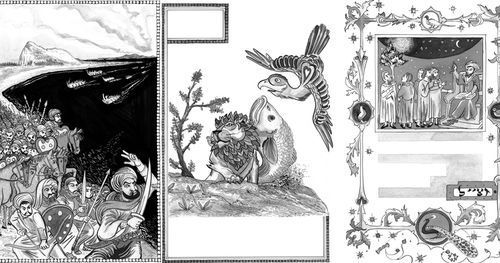

In Megillat Esther, JT Waldman skillfully braids classical commentary on Esther together with the text of the megillah and with his striking and beautiful visual art. He does something similar here, only in this book he's interweaving the story Harvey tells, the experience of hearing that story from Harvey, and Middle East history.

(I'm enclosing a few images in this review to give you a sense for what the book feels like -- I borrowed all of these from JT's site.)

(I'm enclosing a few images in this review to give you a sense for what the book feels like -- I borrowed all of these from JT's site.)

I wish I could show you page 43: it's a beautiful example of the kind of thing that impresses me so much in this book. Top panel: a map of the region, with arrows showing the ingathering. "Those who sought refuge in the holy land found more violence as all-out war erupted between the Jews and Arabs living in the former British Mandate of Palestine." The other text box reads, "With the Arab rejection of the 1947 UN Partition Plan that would have created side-by-side Arab and Jewish states, five Arab states launched war on the Jews."

Move down the page: two boxes, each occupying a parallel space, each depicting armed people firing at one another. On one side, it says "Israelis call this the war of indepedence." On the other side, "Palestinians call it Al-Nakba, 'the catastrophe.'" Two truths, two opposing narratives, juxtaposed in black and white.

Bottom of the page: two vertical boxes. On the left, people walking around the edge of a mass grave: "We Jewish kids were always told how virtuous our people were. It wasn't until I was older that I heard of the Deir Yassin massacre, where in 1948 militant Zionists killed 200 or more Arabs in cold blood." On the right, two distinguished-looking men: "American Jews weren't all saints, either. When I was a kid, I had never heard of gangsters like Bugsy Siegel or Meyer Lansky."

One page; five panels; a glimpse of one hell of a complicated story.

Every few pages, I reach one I wish I could frame. Page 51: four panels depicting Harvey Pekar picking a book of the shelves, flipping through, re-shelving it, all the while musing aloud about how once the Jews went into exile the study of mishna and gemara flourished, "religious acumen became the mark of a great man... and because of their knowledge, rabbis became the most honored men in the community."(I'd hang that in my rabbinic office if I could!)

Every few pages, I reach one I wish I could frame. Page 51: four panels depicting Harvey Pekar picking a book of the shelves, flipping through, re-shelving it, all the while musing aloud about how once the Jews went into exile the study of mishna and gemara flourished, "religious acumen became the mark of a great man... and because of their knowledge, rabbis became the most honored men in the community."(I'd hang that in my rabbinic office if I could!)

Two pages later (p. 53), a page which contains only Arabic calligraphy and non-representational ornament -- and the explanation that in 610, Muhammad began communicating with the angel Gabriel, which was the beginning of what we now know as Islam. The next image of a person we get -- several pages later, after the book has covered the early history of Islam -- is an image of Harvey again, saying, "It's also important to remember that within the Muslim tradition there is a prohibition against making life-like images, even though the Quran doesn't specifically decree it. At various times, Christians and Jews have felt the same. I dunno. Do you see the image of God in me?"

An avowed atheist, Pekar would probably have rolled his eyes to hear that my answer is yes.

Another page I wish I could show you -- 61 -- a house made up of words of prayer and names of places where Jews lived but not easily or safely. 71, conversation amongst bookshelves, featuring the wonderfully acerbic line "Hope, fear, redemption, remembering not to forget...yearning for an impossible future...all the ingredients for a perfect Jewish homeland." The early history of the Jews of Poland, p. 72. The coming of the murderous cossacks, p. 73. There is so much packed into these pages, and each page merits study.

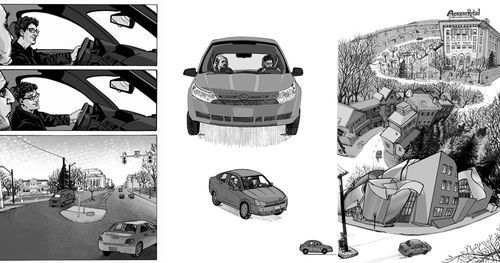

On coming pages there is a history of early Hasidism -- Jacob Frank -- the haskalah, or Jewish enlightenment -- Hebrew's revival as a spoken language. A gorgeous two-page spread (84-85) wherein Harvey and JT, driving across a bridge, talk about what's at the heart of the book. ("I'm just tired of people saying I'm a self-hating Jew because I'm critical of Israel," Pekar's avatar says wearily.) Pekar beginning to question nationalism in the early 1960s. Pekar's attempt to make aliyah, to emigrate to Israel -- and the Israeli consular official's brisk dismissal. The aside where JT tells Harvey what it was like to be living in Israel when Ariel Sharon went up to the Temple Mount. ("You know what the craziest part was? How fast I got used to falling asleep to tank fire outside my window.")

On coming pages there is a history of early Hasidism -- Jacob Frank -- the haskalah, or Jewish enlightenment -- Hebrew's revival as a spoken language. A gorgeous two-page spread (84-85) wherein Harvey and JT, driving across a bridge, talk about what's at the heart of the book. ("I'm just tired of people saying I'm a self-hating Jew because I'm critical of Israel," Pekar's avatar says wearily.) Pekar beginning to question nationalism in the early 1960s. Pekar's attempt to make aliyah, to emigrate to Israel -- and the Israeli consular official's brisk dismissal. The aside where JT tells Harvey what it was like to be living in Israel when Ariel Sharon went up to the Temple Mount. ("You know what the craziest part was? How fast I got used to falling asleep to tank fire outside my window.")

The early 20th century -- pogroms in Europe -- malaria-ridden Jewish settlers in Palestine -- Balfour. (These pages are framed, appropriately enough, in art deco stylings.) Conflicts between Weizmann and Jabotinsky. If you already know these names and these stories, you will be impressed by how thorough this graphic novel history manages to be. If you don't know this stuff yet, you will know it by the time you finish the book -- and it is all valuable context, from the Biblical material on. The 1967 war and its implications. The origins of the settlements, p. 141. The psychedelic swirls of 142-143, in which Pekar wonders, "Does Israel want to rule over a hostile subject people?" and a trio of Hasidim -- singing heads who are also, if you squint, musical notes -- chorus, "Don't worry, God will provide."

"It is a sad state of affairs in the Jewish community," says Pekar on p. 148, "when a rabbi, supposedly a moral leader, vilifies Jews opposed to Israel's commission of atrocities." In the image, he's standing on a page of newsprint, reminiscing about being slammed -- in print -- by one of his own cousins after he published an op-ed critical of Israel. That page may resonate with a lot of readers; I know it resonates with me.

Late in the book, there's a particularly poignant panel where Pekar muses:

What do I know? I make comic books and write about jazz.

I do know the difference between right and wrong, though.

That's one of the last things Harvey says in the book. It ends abruptly -- as his life did. There's an epilogue by his wife Joyce Brabner, which softens the blow somewhat, but the book still manages to end on a suitably off-beat note.

This book doesn't offer answers. But it reminds us what some of the questions are -- and why they are -- and it is honest and brave.This is very much a Jewish book, exploring the Jewish history (or histories, plural) of the land of Israel and of one American Jew's relationship with that place. I hope you will go and read.

June 28, 2012

We are responsible for one another (VR in the HuffPo)

It's a dreadful story. A house of worship burned; hateful graffiti scrawled on the walls; worshipers feeling spiritually homeless, the place to which they would ordinarily turn for consolation now smudged with ash and tinged with hate.

If this had happened to a synagogue, God forbid, Jews around the world would be up in arms. Certainly my rabbinic colleagues and I would be horrified. We would denounce the hate crime from our pulpits, preach loving kindness and consolation, perhaps call in the ADL to condemn the act in the strongest possible terms.

Instead, this month, the house of worship burned was a mosque -- and the burning was almost certainly committed by Jewish hands.

That's the beginning of an op-ed which I wrote a few days ago -- in response to the burning and vandalizing of the mosque of Jabaa -- which has been published in the Huffington Post. You can read it there: We Are Responsible for One Another: Outrage Over Crimes By My Own Community.

New toddler house poem

THE TODDLER ATTENDS A FESTIVAL

You greet the giant dragon

walking high upon his stilts.

Run up to a stranger

and engulf her in a hug.

Spend long giggly minutes

cresting a speedbump on foot.

After the red dancers whirl

you run onto the parquet

to twirl and leap, insisting

NO, mommy, it MY turn!

Dancers and audience laugh

as I drag you back offstage.

When I squirt a line of ketchup

on my own hot dog

your face crumples and you sob

indignant at the imposition

but once you've eaten half a bun

your good mood returns.

Bye, dragon you say in the car

I did dance, mommy

You did, and they all loved you.

Your eyes close; you say I know.

Another "toddler house" poem!

This one comes out of the experience of taking Drew to the Chinese street festival at the Clark. We were only there for about two hours, but we had an action-packed adventure. I hope some of that comes through in the poem. As always, all comments are welcome.

The toddler himself, mere moments before dashing onto the stage...

June 27, 2012

This week's portion: Moshe, the overtired parent

In this week's Torah portion, Chukat, Miriam dies and the Israelites are without water in the desert. Midrashic tradition connects Miriam with a well, often understood as a wellspring of Torah and insight in addition to water; when she dies, the well disappears. The people, predictably, begin to kvetch. "Why did you bring us out of Egypt? We're going to die out here!"

God tells Moshe to assemble the community, order a rock to yield water, and water will arise. But what Moshe does is a little bit different. He assembles the people, he says "Shall I get water for you from this stone?!" and he hits the rock with his stick. Water does arise, and the people drink -- but God is angry, and for this transgression Moshe is barred from entering the promised land.

God is angry, tradition tells us, because Moshe didn't trust him. God promised that if he spoke to the rock, a miracle would occur -- but Moshe brings sarcasm and violence to bear, instead. "What: am I supposed to get water from a stone?"

I believe that the reason Moshe doesn't enter the Land is that the journey is more important than the destination. It's important to have a destination to strive toward, but the real work of the spiritual path is to find holiness in the journey itself. That said, this week I'm interested in Moshe and why he whacked the rock with his stick.

As the mother of a sometimes willful toddler, I feel empathy for Moshe as he listens to the people moan and wail. He's dedicated himself to caring for these people and helping them "grow up" from a slavery mindset to one of freedom and covenant, but do they appreciate him? No: they take every opportunity to yell at him, to stamp their little feet and sit down on the sand and refuse to budge.

Moshe is burned out. And in a moment of exhaustion and overwhelm, he responds to the people's negativity with negativity of his own: whaddaya want me to do, dammit, squeeze water from this stone? Maybe as he looks at the stone he's thinking of his own heart, which right now is feeling dry and unwatered, baked hard as rock.

I like to imagine God's response as a kind of karmic corrective. "Hey, Moses, if you're going to talk to the kids like that? You need a time out. You're coming back to Me."

This year, I find in this parsha a message about self-care. If we ensure that our own emotional and spiritual needs are met, then we become able to respond to those who need us with generosity and compassion. That's when we can use words to work magic -- to cause sustenance to flow where none was there before.

This is the d'var Torah I offered at last night's religion committee meeting at my shul. You can find my other divrei Torah on this portion in the Velveteen Rabbi Torah Commentary

index.

June 26, 2012

Thinking ahead and staying put, or, how a toddler is like a meditation bell

One of the oddities of the congregational rabbinate is that one is always thinking ahead to a liturgical season which hasn't happened yet. Already this week I've solidified our schedule for the Days of Awe. I'm spending time contemplating what my sermons might be, revising selichot liturgy, planning an ad-hoc book discussion group around R' Alan Lew's This Is Real and You Are Completely Unprepared (which I wrote about back in 2006.)

But it's just a few short days after the summer solstice. I want to be enjoying this moment: picking strawberries at Caretaker with my family, enjoying the late long light of evening, getting ready for the congregational Fourth of July picnic next week. And yet I can't help having one foot planted in a season which hasn't yet arrived. I justify it in the name of being organized, planning ahead -- and it is true that this is always the way I have worked best; I am most comfortable when everything is in-progress well in advance -- but I wonder sometimes what might be the spiritual impact of living in the future instead of in the now.

It's a little bit like looking ahead to a much-anticipated vacation. On the one hand, imagining the vacation and planning how it might go can extend the pleasure well beyond the days of the trip itself. First you get to enjoy thinking about it in advance; then you get to go; then you get to enjoy remembering it afterwards! It's a triple blessing that way. And on the proverbial other hand, the danger in this kind of anticipation is that it can provide an easy opportunity to escape whatever's happening now. Plus, getting attached to expectations means running the risk of disappointment if and when something changes or the expectations don't come to pass. (See How to avoid having a strop & the secret to happiness, which Fiona just posted yesterday at Writing Our Way Home.)

So maybe the real question is, what are good tools for maintaining balance? How can I ensure that if I spend all morning with my head in the clouds of Elul and Tishri, I return to the present moment? That if I lose myself in daydreaming about a weekend with friends in late summer, I return to where I am now?

In a funny way, having a toddler is an excellent antidote to the tendency to get lost in the future or the past. Drew lives pretty much in the now. I think he can grasp the idea of immediate future (it seems to be helpful when I outline for him what the morning is going to hold, or how long a playdate is going to last), and I know he remembers the past -- but often he brings the past right into the present, narrating things we did days ago as though they were happening right now. Maybe for him they are.

A toddler is like a meditation bell, forever calling me back to the now. In meditation each Friday morning, I often remind myself (and those who are sitting with me) that the mind will wander; that's what minds do. Having thoughts is what minds are for! So when our minds wander, as they inevitably do, we can notice that without judgement and call them back to the present moment, this breath, right here, right now. Drew does that for me a million tiny times a day. "Want to play catch, mommy?" Catch. Yes. My son is right here, and I was distracted, but now I'm back. "Want to read Oh My Oh Dinosaur?" Of course, climb into my lap and I will read to you.

I remember thinking, last summer, as I was first settling in to my pulpit, that it was a tremendous blessing to have a reason to leave work at 4pm and take my child to a playground every day. (Indeed: that the whole world would be healthier if we all had to stop working after eight hours and spend some time playing instead.) I don't think I knew how true that would continue to be. I'm grateful to be part of a liturgical / spiritual tradition which flows throughout the year, like waves, going and returning: the cycles of day and week and month, the cycles of festivals which lead one to the next. I'm grateful to have reason to place myself out of time, to prepare for the holidays which are coming. And I'm also grateful to have a child who, without knowing it, reminds me every day to return to him and to myself and to right now. Right now. Right now.

June 24, 2012

Looking back at camp after eighteen years

Eighteen years ago, my sister gave birth to a daughter. I wrote a poem for her from far away; I think I sent it in a letter for her baby naming. I was working, that summer, as a cabin counselor at the Greene Family Camp for Living Judaism in Bruceville, Texas. I came out of that summer yearning to become a rabbi. I don't think I imagined the roundabout path I would take to make my vocation real.

That summer is a mixed bag in memory. I liked my campers, but I was lonely. Most of the other counselors had been campers for years; I had only attended Greene once, when I was nine. Most of the other counselors had pledged Jewish sororities and fraternities at UT; I had chosen a small liberal arts college in western Massachusetts which eschewed the Greek system altogether. The other counselors were perfectly nice -- we were just coming from different places, and at nineteen that isn't always easy.

I remember writing poems about the Berkshires, wistfully remembering the crunch of boots on snow as I sat on our cabin's cement porch in the evening heat. I remember Friday afternoons, when the whole camp dressed in white and we all walked together slowly to the limestone ampitheatre for kabbalat Shabbat. I remember the Friday night song sessions after dinner, led by camp director Loui Dobin -- that experience of singing Hebrew songs, sometimes jumping up and down with sheer enthusiasm, swept me up and carried me away.

And I remember the rabbinic students. There were a handful of Reform rabbinic students there, doing their summer stint at Greene because it is one of the movement's camps, and they were kind to me. Maybe I told them I was majoring in religion. Maybe they just recognized me as a kindred spirit: who knows? But they invited me to study with them, and on some nights when I wasn't on-duty after lights-out I would go to their building and pore over Torah with them, unutterably proud when I could translate something or could add an insight.

I wasn't very good at the extroverted parts of being a camp counselor. The high energy of Maccabiah (when everyone in the camp divided into four teams, dressed in team colors, and competed in all manner of sports and games, complete with team cheers and face-paint) overwhelmed me a little. So did the chaotic atmosphere of the last night of each session when the kids would stay up all night talking, bedtime rules suspended because they were going home in the morning. But I loved the times when I could connect with the kids one-on-one.

Some of my campers confided in me when things were tough. Family difficulties, sickness or divorce -- sometimes they came to me for solace, and I comforted them as best I could. In a funny way, those are some of my sweetest memories of the summer: times when I felt I was able to make a difference. One of the rabbinic students was present for one of these encounters, and after I had hugged the camper and sent her on her way, he quietly murmured to me, "Nice work, Rabbi." I glowed for days.

I wish there were a way to give my nineteen-year-old self a glimpse of my life now. Married to my sweetheart whose photo I displayed on my shelf next to my bunk that summer, who had then just returned from his Fullbright year in Ghana. (As it happens, he's in Ghana even now -- there's a reason his blog is called "My heart's in Accra.") Rearing our beautiful son. Ordained a rabbi, and serving a small congregation in the Berkshires with honor and joy.

That my Boston niece is ready for college is easy to believe. She is smart, thoughtful, introspective -- a young adult ready for her next adventure. What's hard for me to swallow sometimes is that she is very nearly as old now as I was when she was born. I wonder what she'll remember, what she'll regret and what she'll treasure, in eighteen years.

June 22, 2012

Walking meditation

Had there been a small plane taking off from the tiny North Adams airport this morning, the pilot would have seen half a dozen people walking very slowly in meandering loops around the mown grass behind the synagogue.

We moved like bridesmaids in a wedding procession: step -- pause. Step -- pause.

Some of us had our eyes closed. One person stopped and stood, rooted to the great rotating ball of the earth.

One person's tallit fluttered like irridescent rainbow wings.

June 21, 2012

New Torah poem - inspired by the book of Amos

SUBTERRANEAN

Amos stands on a subway platform

littered with stubbed-out cigarettes.

For three sins, even for four,

I will not reverse it! The commuters

skirt his dirty robes, avoid eye contact.

He rails about forgiveness

and fire, the sun going dark at noon

and if anyone listens, they roll their eyes

at the homeless guy who doesn't know

an eclipse from an apocalypse.

Late afternoon he loses steam

-- hungry or disheartened; does it matter?--

and curls into his cardboard box

trying to disappear. The clink of coin

startles him: a woman with greying hair

crouches at his feet, waiting for him to see.

She merges back into the crowd.

Justice will well from the deepest trench,

he mutters, righteousness like waters

flooding a dry ravine. He rises,

the money clenched in his dirty palm.

You will slink into your ruined cities

and drink from your vineyards again!

Rush hour again: but for this one moment

he doesn't mind that no one hears.

This poem arises out of the prophetic book of Amos. It was also inspired, however obliquely, by the blog post Cup, written by my friend Beth at The Cassandra Pages. (Beth is also my editor at Phoenicia.)

Recasting a Biblical prophet in the role of a contemporary homeless man (or, I suppose, comparing the rantings of the Biblical prophets with the ravings of someone who is disheveled and quite possibly mentally ill) is nothing new. But I like the idea that a gift of momentary connection, a gift of being seen, might be enough to spark the light of forgiveness even in someone who has suffered greatly, or someone who speaks for a suffering God.

June 20, 2012

Two poems from Before There Is Nowhere to Stand

I mentioned a while back that I have two poems in Before There Is Nowhere to Stand, an anthology of poems arising out of Israel / Palestine.

I mentioned a while back that I have two poems in Before There Is Nowhere to Stand, an anthology of poems arising out of Israel / Palestine.

I hope, over time, to make several posts about this anthology. No two poems in this collection tell the same story. Often any two poems tell very different stories. What makes this anthology so powerful (and, I think, so valuable) is this juxtaposition of two narratives which are on the one hand irreconcilable -- and on the other hand, what transformation might be possible in all of us if we were able to truly enter into the story as it is experienced by the "other side"?

Here are two poems which moved me deeply as I began reading the book. One poem is by Rick Black, a book artist and poet, the founding editor of Turtle Light Press. He lived in Israel for six years, studying literature at Hebrew University and then working as a journalist in the Jerusalem bureau of the New York Times. The other is by Reja-e Busailah, who has been blind since infancy, and who (along with his family) was forcibly evicted from his home in Lydda into exile. Educated in Cairo, he earned a PhD in English from NYU and taught for thirty years at Indiana University.

Take a deep breath and enter into the words of these two poets. If you want to talk about the poems or their impact on you, perhaps conversation will unfold in comments.

BOUGAINVILLEA by Rick Black

Candles are not yet

aglow like sapphires,

the braided challah is still uncut,

quiet beckons

and the last #18 bus

is packed.

People are returning from Mahane Yehuda,

the outdoor market of Jerusalem --

inhale the scents of cinnamon, cardamom and curry,

piled high in mounds,

the barrels of pickles, sour and half sour,

the pickled herring, creamed herring, matjes herring

and piles of fresh dates, smooth and sweet,

and chocolate ruggelach and babke, oval sesame rolls

challahs with raisins, and hot pita

and crowds shoving, bustling, hustling, bargaining, shouting, mobbing,

elbowing each other, shuffling along beneath the bare electric bulbs

hanging,

suspended like the lights of the George Washington Bridge

above the ducans,

"Melafifon -- 40 shekels."

"Tut, tutim -- fresh strawberries. Pilpale -- peppers."

Dressed in streimels, flowing robes, silk skirts, pushing

baby carriages, shlepping plastic shopping bags,

speaking a mélange of tongues -- Hebrew, Arabic, French, English and German --

shoppers ebb and flow like waves rushing and receding

from shore,

from one merchant to another. They gather like flocks

of seagulls, then disperse past the green-leaved clumps

of garlic, bulbous clumps, dry, hard like the noses of passersby,

bright, shiny eggplants, globular. Go ahead,

imbibe the scent of fresh cut oranges, tongue the bits of halvah,

gently press the avocado skins and squeeze the tomatoes

at dusk on Shabbat,

and taste the loaves of challah woven into the prayer shawl

of our people's history.

Emitting plumes of black diesel smoke

the bus leaves the market, stops at the Central Bus Station

and chugs up Mt. Herzl into the ethereal, blood-soaked air

of Jerusalem

and there --

in the fading, tarnished light descending

on the city and the Jerusalem pines --

just past Yad Vashem --

there,

the bus, its red and white sides gleaming,

clinging to the hill stubbornly

and climbing it like bougainvillea,

there

the bus explodes:

skewering flesh, shattering glass, shrieking in the quiescent streets,

and sobbing,

there

overturned like a beetle

helpless, writhing, unsilent

there

like a crushed violin

its mangled strings

twisted

notes

shrieking in the sky

and the ambulances wail

"Holy, holy, holy!"

and the pines

in the golden, Sabbath sunlight,

(for candles will soon be lit),

glow ineffably, more beautiful

than ever,

and God remains

in his own way, silent.

We are near Ein Kerem,

Ein keloheinu, ein, ein, ein...

There is no

God

like our God.

There is no

king

like our king.

There is no

redeemer

like our redeemer."

And the angels cry

and the ambulances wail

and survivors lie on the pavement, wounded,

having fallen back down

in the Vitebsk street,

a violin's strings

broken. But, if you listen

carefully,

perhaps you'll hear wind

in the pines,

perhaps you'll see

starlight glisten

off shattered glass,

and off bougainvillea petals

that are still climbing,

reaching up

in prayer.

IN THE SHADOW OF THE HOLY HEIGHTS by Reja-e Busailah

for Haniya Suleiman Zarawneh, killed by the Israelis

at the age of 25, near Jerusalem, January 4, 1988

The sun came out that day from the depth of winter

like the rare orphan of good luck --

what else can the light of heaven be

on a day rising from the dead of winter?

And she had risen before the sun that day

and like her mother and grandmother before her

she washed by hand and wrung by hand

the linen for spouse and child,

and like mother and grandmother

she walked up the wooden ladder

with the pail onto the roof

into the shadow of the Holy Heights --

so clear was the sky

it almost recalled the sight and the scent of the sea down west.

Faithfully she hung her labors on the rope

article by article

that the good sun might dry them for her,

she clasped each with a wooden pin

as safeguard against the prankish wind --

it was no senseless nature that did it when she was done

just about to come down for other chorse,

it was no fiendish Nazi,

it was one of the Chosen

selected her heart for his anointed lead

so that limp went the spring int he covenant

which joined soul and limb --

and the good sun shines

and the sheets and the skirts and the nightgowns

and the small socks

and the outfit for the wooden doll

they toss in the wind

and smell like linen hand-washed and sun-dried

they swing lighthearted on the rope

waiting for mother to collect them

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers