Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 214

August 28, 2012

Revision / reprint of a poem from 2003

NO ALTERNATIVES

I don't want to write about the girl

killed by an Israeli bulldozer while

trying to protect a Palestinian home.

Don't want to write about mentioning it

in casual conversation and finding myself

weeping uncontrollably into my dishtowel.

Don't want to write how politics

have infected every email list I'm on,

how poets across the nation are arguing

whether those who voted Green

in the year 2000 got us into this mess

instead of debating the merits of form

and free verse like we used to. I thought

those arguments were dull, repetitive, but

today I'd pay to see my inbox overflowing

with impassioned pleas for a return

to iambic pentameter, diatribes about

how "women's poems" differ from whatever

the alternatives are. I don't know what

the alternatives are. I keep lending out

that article about healing through "dark" emotions,

the one that says anger and sorrow

aren't the problem, the problem is

when we stamp and tamp them down

so the pressure of our denial shapes

the slicing stone-edges of despair, but

I can't see the darkness around us lifting.

I've always said hopelessness

isn't an option, if we don't believe

in tikkun olam we might as well be dead, but

I don't know how to get through this.

This is not a poem about "them" or what

they're doing to "us," this is not a poem about

politics or regime change, this isn't even

a poem about the horror of Iraqis hissing

that the mothers of the American soldiers

will weep tears of blood, or the shame

of Americans braying that those people

are animals, not like us, don't respect life.

This is a poem about forestalling despair

by taking a breath and diving as far as I can,

wishing that I could surface in a kinder world.

This is a revision of a poem I wrote in spring of 2003, around the time of the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the death of American activist Rachel Corrie. It was originally published in The Pedestal in the fall of 2004 (see Rachel Barenblat: No Alternatives.)

I returned to it this week in the wake of the court decision exonerating the Israeli government of responsibility for Rachel Corrie's death. The poem has changed shape, I've trimmed a bit (from 51 lines down to 42), and there's a new ending. If you read both the new version and the original, I'll be curious to hear which one you think is a better poem.

Some of this poem feels dated to me now, even in revision. The Iraq War has been a reality of our world for so many years that it's hard to remember what it was like to think that we could have prevented it. But some of this poem still feels current (war, despair, hatred: unfortunately not out of style), and the ending speaks directly from my heart.

The "article about healing through 'dark emotions'" was an essay by Miriam Greenspan in Tikkun. It later became a book with that same title.

Cultivating equanimity

Equanimity (השתוות / hishtavut) is very important. That is, it should make no difference whether one is taken to be an ignoramus or an accomplished Torah scholar. This may be attained by continually cleaving to the Creator -- for if one has devekut [deep connection with God], one isn't bothered by what other people think. Rather, one should continually endeavor to attach oneself to the Holy Blessed One.

That's a teaching from Tzava'at HaRivash, the collected teachings of the mystical Jewish rabbi known as the Baal Shem Tov. (A different translation of this passage appears here at Chabad.) This Eul, I find myself returning to this teaching again. I admire the ideal of equanimity, of responding to whatever arises from a place of centered acceptance and calm. As long as I do my best to be the kind of person I mean to be, to serve God and my communities in the ways I strive to serve, then that's what matters most. If I focus on my connection with something greater than myself, then I can handle things which seem in my limited understanding to be "good" or "bad" with equal grace and presence.

Even if life throws me curveballs, even if something goes wrong or if someone thinks ill of me, shouldn't I be able to hold fast to my faith and my spiritual practice, and to accept both the good and the bad with a whole heart? All I need to do is maintain mindfulness of God's presence -- as the psalmist says, and the Baal Shem reminds us, שויתי ה' לנגדי תמיד; "Sh'viti Adonai l'negdi tamid / I have kept God before me always." (The word shviti, "I have kept," shares a root with hishtavut, equanimity.) "Good" and "bad" are limited human concepts; from the perspective of the divine, whether someone calls one an ignoramus or admires one as a Torah scholar is beside the point. This is, I think, what the Baal Shem Tov is saying.

Early American shviti papercut; 1861. (Source.) A shviti is a meditative focus: we look at it and are reminded to keep God before us always, as the verse from psalms says.

When I had my strokes, several years ago, I spent a lot of time talking with my mashpia (spiritual director) about equanimity. I was struggling to come to terms with what had happened to me, and with my desire to know why I'd had the strokes and to reach some certainty that I wouldn't have another one. My mashpia at the time brought a variety of BeShT teachings to bear on our conversations. (I touched on this in my 2009 essay Different Strokes.) I seem to remember that I was able fairly easy to respond with equanimity to the immediate experience of the strokes; I found it more difficult to maintain equanimity as we moved into the realm of longterm medical uncertainty.

Maybe because spiritual lessons recur as our life circumstances unfold, this Elul I find that I'm working again on cultivating this middah (this quality) within myself. There's much in the world today which challenges my equanimity.

I know in my heart that the Baal Shem Tov was wise, on this issue as on so many. If I could encounter rejoicing and sorrow alike without being shaken, if I could receive insults and compliments alike without paying either one any mind, remaining focused on connecting with the Holy One of Blessing and bearing in mind what's really important (pro tip: not my own ego), that would be a high spiritual state indeed. I try, every day, to get a little bit closer. I do know that when I'm able to achieve something like devekut -- cleaving; attachment to God; deep connection with something far beyond myself -- everything in my life, both good and bad, takes on a different tone.

Sometimes I reach a kind of devekut when I'm leading prayer and we reach the bar'chu, the call to prayer. I find sometimes that when I'm playing guitar and singing the bar'chu something shifts in me. I can feel my voice changing, coming from somewhere deeper in my body. It's as though I'm no longer praying the prayer; instead the prayer is praying me. In that moment of singing and praying and praise, it doesn't even occur to me to wonder whether I'm leading a good service, or whether people like what I'm doing. It doesn't occur to me to remember that unkind thing someone said last week or the mean-spirited email I got the other day.

Sometimes I reach a kind of devekut when I am cuddling with my son. At night, him in his pyjamas, the two of us in the gliding rocker where we used to nurse. I'm singing him his goodnight songs, he's giggling and squirming in my arms, and I catch his laughter and then I'm connected to something so much bigger than myself. In those moments I forget my consternation at reading the news; I stop dwelling on mistakes and unkindnesses. It's like the Sfat Emet teaching about Purim, where one ascends so high -- beyond the top of the tree of knowledge of good and evil; beyond dualities -- that everything is good, everything is God.

I'm not sure that's equanimity; it's more like bliss. Maybe equanimity is the quality which enables us to encompass both the moments of blissful connection and the moments of agonizing disconnect. Because I can't stay in that lofty headspace and heartspace, no matter how I wish I could. At some point, we always have to leave mochin d'gadlut (expanded consciousness or "big mind") for mochin d'katnut (constricted consciousness or "small mind.") For me, the question is: once I'm back in "small mind," how will I respond to the world around me? How will I respond to injustice, to unkindness, to lack? How will I respond to compassion, to connection, to joy?

Striving for equanimity helps me respond to my life with gratitude, to relate to the world at large with the kindness and compassion I most value. Sometimes I manage it, for a while. Then something shakes me and my balance wobbles. Then I take a deep breath and seek balance again. I don't think equanimity is something one reaches once and then the journey's over. There's a reason we use the language of gardening to describe this kind of work: it's a slow and steady cultivation. Once it's planted in the heart, equanimity may be a perennial (to run with that metaphor a bit further), but it still requires tending, and watering, and care.

August 27, 2012

This is real, and I want to be prepared: Elul, Selichot, and Rosh Hashanah

This coming Shabbat at my shul we'll continue discussing one of my favorite books: This Is Real And You Are Completely Unprepared: The Days of Awe as a Journey of Transformation by Rabbi Alan Lew. I've posted about it several times before. I try to make a practice of rereading it each year as we move through this season. This year, I'm sharing that practice with my community.

This coming Shabbat at my shul we'll continue discussing one of my favorite books: This Is Real And You Are Completely Unprepared: The Days of Awe as a Journey of Transformation by Rabbi Alan Lew. I've posted about it several times before. I try to make a practice of rereading it each year as we move through this season. This year, I'm sharing that practice with my community.

If you live locally, I hope you'll join us at CBI this Shabbat for a

discussion of the middle three chapters of this book (come at 11am -- or

join us at 9:30 for davenen first!) We'll be discussing chapters 4-6: "The Horn Blew and I Began to Wake Up: Elul," "This is Real and You Are Completely Unprepared: Selichot," and "The Horn Blows, the Gates Swing Open, and We Feel the Winds of Heaven: Rosh Hashanah." (Even if you don't have a copy, or haven't done the reading, you're welcome to join us; I've put together a handout of choice quotes from these chapters which should give us plenty to talk about.)

And for those who don't live nearby,

I thought I might share those choice quotes here, along with a few thoughts about them. I hope you'll find these passages as thought-provoking and inspiring as I do.

"Look! I put before you this day a blessing and a curse." So begins parshat Re'eh, the weekly Torah portion we read as the month of Elul begins. Look. Pay attention to your life. Every moment in it is profoundly mixed. Every moment contains a blessing and a curse. Everything depends on our seeing our lives with clear eyes, seeing the potential blessing in each moment as well as the potential curse, choosing the former, forswearing the latter. (pp. 65-66)

I really like the way R' Lew connects his Elul teachings with the flow of the Torah portions we're reading this month, and I like what he has to say about this blessing-and-curse passage (which is, as it happens, also the portion my community reads on Yom Kippur morning.)

[T]he month of Elul -- a time to gaze upon the inner mountains, to devote serious attention to bringing our lives into focus; a time to clarify the distinction between the will of God and our own willfulness, to identify that in us which yearns for life and that which clings to death, that which seeks good and that which is fatally attracted to the perverse, to find out who we are and where we are going.

All the rabbis who comment on this period make it clear that we must do these things during the month of Elul. We must set aside time each day of Elul to look at ourselves, to engage in self-evaluation and self-judgement, to engage in cheshbon ha-nefesh, literally a spiritual accounting. But we get very little in the way of practical advice as to how we might do this. So allow me to make some suggestions.

* Prayer -- The Hebrew word for prayer is tefilah. The infinite form of this verb is l'hitpalel -- to pray -- a reflexive form denoting action that one performs on oneself. Many scholars believe that the root of this word comes from a Ugaritic verb for judgment, and that the reflexive verb l'hitpalel originally must have meant to judge oneself. This is not the usual way we think of prayer. Ordinarily we think we should pray to ask for things, or to bend God's will to our own. But it is no secret to those who pray regularly and with conviction that one of the deepest potentials of prayer is that it can be a way we come to know ourselves. (pp. 67-68)

I love the fact that our Hebrew word for prayer connotes judging oneself, looking inward, coming to know oneself. Because boy, do I agree with Rabbi Lew on this one: regular prayer, like regular meditation practice, is a way of coming to know my own internal landscape and coming to understand myself in a deeper way.

* Focus on one thing -- It may not be realistic to expect a significant number of people to suddenly begin showing up at prayer minyans or meditation groups during the month of Elul -- some of us are simply not made to engage in these activities; not in Elul, not ever. Many will never get over finding the daily prayer service tedious and opaque. Many others will always either be frightened to death or bored to tears by the prospect of meditation and the blank wall of self it keeps throwing us up against so relentlessly. So I am pleased to inform you that it is perfectly possible to fulfill this ancient imperative to begin becoming more self-aware during this time without doing these things... Just choose one simple and fundamental aspect of your life and commit yourself to being totally conscious and honest about it for the thirty days of Elul. (p. 72)

I love the way that, after spending many paragraphs describing prayer and meditation and how valuable they can be, he acknowledges without judgement that for many people, they just don't work. Daily prayer can be tedious and opaque; meditation can be either terrifying or deadly dull. But, he says, that's okay! You don't actually have to do those things! What Elul calls us to do is to be conscious, to be present, to be awake. Just choose one aspect of your life (he suggests a few, among them eating, sex, and money) and be totally conscious and honest about it for thirty days. Easy, right?

Rabbi Lew cites a medieval midrash which says that King David knew the temple would someday be destroyed, and he was worried: how would we make atonement then? So God said to David, when troubles come upon Israel, let them stand before Me together as a single unit, make confession before me, and say the selichot (forgiveness) service before Me, and I will answer them.

It's a beautiful midrash. (Reading it now, I'm struck by the notion that the community of Israel needs only to stand before God together as one. Sounds so simple, and yet it's all too easy to imagine how the divisions within our community could keep us from being able to enact this instruction.) He continues:

The first thing we do during the High Holidays is come together; we stand together before God as a single spiritual unit... We heal one another by being together. We give each other hope. Now we know for sure -- by ourselves, ain banu ma'asim, there is nothing we can do. But gathered together as a single indivisible entity, we sense that we do in fact have efficacy as a larger, transcendent spiritual unit, one that has been expressing meaning and continuity for three thousand years, one that includes everyone who is here, and everyone who is not here, to echo the phrase we always read in the Torah the week before the High Holidays begin -- all those who came before us, and all those who are yet to come, all those who are joined in that great stream of spiritual consciousness from which we have been struggling to know God for thousands of years. We now stand in that stream, and that is the first thing we do. (pp. 110-111)

This is incredibly powerful for me. The way we formally begin the Days of Awe is by coming together: physically (as we gather in our synagogues and community centers and retreat centers and at Occupy campsites and wherever else it is that we congregate) and emotionally/spiritually. At this season we are called, more than ever, to understand that we are part of something much greater than ourselves. Greater than our own community. We're part of something which stretches back for thousands of years, and -- God willing! -- stretches forward even longer. We're part of something infinite. And we can find healing in the simple fact of our togetherness.

At Tisha b'Av we became aware of our brokenness; during Elul we cultivated an awareness of our actual circumstances, the dust that we will return to, the fragility and impermanence of our life. If we succeeded in awakening to our lives we saw clearly how every moment of our lives, every breath, every thought, is only a passing shadow, a fugitive cloud, a fleeting breeze, a vanishing dream. This being the case, how do we acquire a toehold in this world sufficient to do Teshuvah? (p. 115)

I struggle with the reality of impermanence. Sometimes I think I'm comfortable with mortality, with change, with how fragile our bodies and our lives can be. Other times, I can't bear to think that everything I know, everything I love, everything I try to do, is fleeting and fragile. But this is a month when that reality keeps bubbling up and reminding us of its presence. Rabbi Lew takes that idea and turns it into something surprising and beautiful:

Rosh Hashanah is, among other things, Yom Harat Ha-Olam -- The Day the World Is Born. Rosh Hashanah is also the day that the world burst into being out of nothing, and it stands for both that event and its continuous renewal. Every moment of our lives the world bursts into being out of nothing, falls away, and then rises up again. Every moment we are renewed by a plunge into the void. This void is called heaven. There is a void at the beginning of creation and a void afterward. Life is the narrow bridge between these two emptinesses. Usually all our focus is on the narrow bridge of our own life, rather than on what comes before or after. In its accounts of both the death of Moses and the creation of the universe, the Torah focuses our attention instead on the void. (p. 116)

I love the way he moves here from the idea that Rosh Hashanah is the birthday of creation, to the reminder that creation is reborn in every moment, to the teaching that we too are reborn in every moment, to the reminder that we can find God in emptiness. Our lives, he says, are the narrow bridge between the void before we were born and the void after we were born. But God is in the void. We come from God, and we return to God. At the end of this festival season, at Simchat Torah, we'll read the very tail-end of the Torah (Moshe's death at the end of Deuteronomy) and then read the very beginning of the Torah (the creation of the universe at the beginning of Genesis.) The end of the story and the beginning of the story. Death, and birth. For Rabbi Lew, this is a reminder of the void, the impermanence, the great nothingness before and after our own lives. And in that void, that great emptiness, is always God.

Holiness is the great nothing that appears in all the religious traditions of the world in various poetic guises. It is an ineffable intensity, an oceanic sense, a warm flash of light, a marriage of the soul, a mighty wind of resolution, a starry grace, a burning bush, a wide-stretching love, an abyss of pure simplicity, and as we have mentioned, it is the word the angels cry, the word that rings throughout heaven. In short, holiness is an all-encompassing emptiness. In short, holiness is heaven. And Rosh Hashanah is all about our connection to heaven. Rebbe Nachman of Bratzlav said that when the shofar blows 100 times on Rosh Hashanah, a bridge is formed between heaven and earth. (p. 122)

This is such a beautiful passage that I just want to read it over and over. "It is an ineffable intensity, an oceanic sense, a warm flash of light..." And I love the idea that Rosh Hashanah is all about our connection to heaven. Then, a few pages later, Rabbi Lew connects this idea with the theme of forgiveness:

Self-forgiveness is the essential act of the High Holiday season. That's why we need heaven. That's why we need God. We can forgive others on our own. But we turn to God, Rbabi Eli Spitz reminds us, because we cannot forgive ourselves. (pp. 126-127)

This feels true to me. We can forgive each other, if we try. But it can be so hard to forgive ourselves for all of our perceived failings. Can you forgive yourself for every unkind word you've spoken this year, for every place where you've fallen short of your best self, every mistake, everything you've said that you regret, everything you didn't do but wish you had done? This, Rabbi Lew says, is why we turn to God. We turn to God because God is the source of forgiveness. We turn to God because we need to feel forgiven.

The real work we have to do at this time of year, I think, is to find compassion no matter what. But we have to find it for ourselves before we can be of much use to others. (p. 134)

I'm not sure that this work is limited to this season, but I think he's right that it's extra-important right now. As we move into teshuvah, into examining our lives and our choices, we have to do so with compassion and kindness for ourselves. Otherwise the process of self-judgement would be too painful to bear. And once we can be compassionate with ourselves, we can be that way with others, too.

We keep trying to pose for the snapshot of our life, but at Rosh Hashanah, our deepest need is to see the tape. And there really is such a tape. In fact there is a whole set of tapes. There is the Book of the World. There is the Book of the Body, the Book of Life, and the Book of the Heart. (p. 140)

This is a riff on the idea that we each write the book of our lives with our actions, and that during the Days of Awe, the book of our lives is opened and God reads what we have written. But I love his broadening of this metaphor. We write our lives on the book of the world. Look at the world around us: how do we treat the world? How do we inscribe our hopes, and also our fears and our shame, on the world around us? We write our lives on the book of the boyd. Look at your own body: how do you treat your physical self? Do you starve it, do you give it nutrients it doesn't need, do you work it too hard, do you neglect it? Do you love your body, or do you resent it for not being what you hoped it would be? And then he moves further inward, to the book of the heart:

After the Book of the World and the Book of the Body, the truth of our life is also written in the Book of the Heart. We can feel it there, pressing up against our rib cage. It is perfectly self-evident. All we have to do is read it. If we just stop and quiet ourselves, our broken hearts announce themselves. We know our disappointment very well. We know our shame and our failure. During the Days of Awe, we pound our heart repeatedly as we recite the Vidui, the confessional prayer that is repeated over and over again in the High Holiday liturgy. We point at the heart. We pound at the heart until it opens and we can read it. Why does it take such an effort? Largely, I think because we don't feel safe about exposing our hearts. (p. 146)

We don't feel safe about exposing our hearts. Not to the world; often, not even to ourselves. But this season offers opportunity to do just that. In our communal togetherness, we can open our hearts safely. We're all going there together.

Here's the last quote I'll offer from this section of the book. I find this one incredibly powerful and poignant. I hope you do, too.

At Rosh Hashanah we begin to acknowledge the truth of our lives. The truth is written wherever we look. It is written on the streets of our city; it is written in our bodies; it is written in our lives and in our hearts. We have a deep need to know this truth -- our lives quite literally depend on it. But we can't seem to get outside ourselves long enough to see it. And besides, we are terrified of the truth.

But this is a needless terror.

What is there is already so. It's on the tape. Owning up to it doesn't make it worse. Not being open about it doesn't make it go away. And we know we can stand the truth. It is already here and we are already enduring it.

And the tape is rolling. The hand is writing. Someone is watching us endure it, waiting to heal us the moment we awake and watch along.

From the great pit of our heart, we sense the seeing eye, we sense the knowing ear, watching the drama of our lives unfold, watching it with unbearable compassion. (p. 150)

The tape is rolling. The hand is writing. Someone is watching us endure it, waiting to heal us the moment we awake and watch along.

Wishing you every blessing as we move through Elul and Selichot toward Rosh Hashanah.

August 26, 2012

Wishing for a different communal discourse

Late last week, I was forwarded links* to two Republican organizations trying to shame Rabbis for Obama by mis-representing several of the rabbis in that group (particularly Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb) as "anti-Israel activists."

Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb first traveled to Israel in 1966, when she spent a year as an exchange student at Leo Baeck High School in Haifa. She experienced the call into rabbinic service the Shavuot she was fifteen, when she gave a speech called "Man and the Moral Law." (Women didn't begin receiving rabbinic smicha in the United States until Rabbi Sally Priesand in 1972, but Rabbi Gottlieb was one of the first eight women ordained as a rabbi when she was ordained in 1981.) Her first pulpit was Temple Beth Or of the Deaf. She's a trailblazer in the field of feminist liturgy (I use one of her poems in my seder each year.) And she's the coordinator of the Shomer Shalom Network for Jewish Nonviolence. A few years ago I interviewed her for Zeek, along with several other rabbis, in a roundtable about Israel: Roundtable: The Synagogue/ Israeli Politics Mash-Up. She is not anti-Israel, and neither are the rest of us who have subsequently been called out.

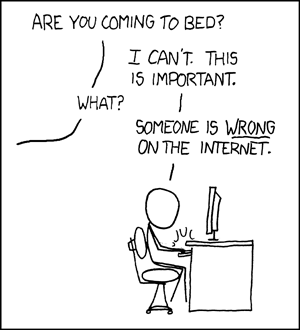

As this has unfolded, the xkcd cartoon has come to mind:

"Someone is wrong on the internet!" Courtesy of xkcd.

The cartoon is funny because it's true. Of course some part of me wants to rise to the bait, to correct the record because what is being said is not true. And then I think: why would I allow people who misrepresent us in these ways to define the terms of the conversation? And why does it matter to me that someone is, as the cartoon says, wrong on the internet?

In the days since the Rabbis for Obama list was released, the Republican Jewish Coalition and the right-wing Emergency Committee for Israel have responded by claiming that several of us on the Rabbis for Obama list are "anti-Israel activists" because we're members of the Jewish Voice for Peace rabbinical council. JVP seeks security and self-determination for Israelis and Palestinians, an end to violence against civilians, and peace and justice for all peoples of the Middle East. (Source: JVP mission statement.) This is not anti-Israel.

But regardless of one's opinion of JVP, what the RJC and the EIC are doing is attempting to draw lines around who is and who isn't sufficiently pro-Israel (according to their own definitions thereof), and I think that kind of policing hurts our community. This rhetoric is meant to sow divisiveness in the service of political gain. It has a chilling effect on our communal discourse. And it acts to silence many progressive Jews and to exclude us from the table. The fact that election season brings out some of our country's nastiest rhetoric is unfortunate but not surprising; but it still saddens me to experience it within the Jewish community.

It's the month of Elul. This is our time to connect with the divine Beloved; to walk in the fields with God and pour out the prayers of our hearts. As I sat in meditation on Friday morning, I noticed that my mind kept returning to this situation. As a result, these last few days, one of the prayers of my heart has been: God, why is there so much anger and misunderstanding in the world? Why, when we have so much in common, do we focus so often on our differences and use those as an impetus toward unkindness?

It's the month of Elul. This is our time to deepen our work of teshuvah, of discernment and soul-searching and re/turning-toward-God. I'm hoping that reading these posts, and finding myself experiencing a range of emotional responses to them, can feed my process of teshuvah. This offers me a shining opportunity to become more aware of the depth of my desire to build bridges and to create understanding -- and also to recognize the continuing challenges of relating to (what seems to me to be intententional and willful) misrepresentation with equanimity.

During Elul it's traditional to read Psalm 27 every day. My favorite translation is by Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, and rereading it lately, I've been resonating with different lines than usual. I always love the lines asking to dwell in God's house (which I sing all the time at this season.) Lately I'm also struck by "Discourage those who defame me / Because false witnesses stood up against me belching out violence." Though what I really wish is not for those who defame us to be discouraged, but for us to better understand one another.

Why does it matter to me that someone is "wrong on the internet"? Because this is part of a bigger picture of people trying to define who's "in" and who's "out;" because this is part of an attempt to define me, and my colleagues, with words we would not use to describe ourselves; because labeling us as "anti-Israel activists" is not only factually wrong, but also hurtful; because this is part of an attempt to bully and silence those of us in the Jewish community who criticize Israel's policies, and I don't think it's wise or healthy to create a situation in which anyone who critiques Israel is considered beyond the pale.

Accusing fellow Jews of being insufficiently pro-Israel is a way of creating and strengthening divisions between us. It damages the fabric of klal Yisrael, the greater Jewish community. It's only a few weeks since Tisha b'Av, when many of us study the text from the Babylonian Talmud (tractate Yoma 9b) which tells us that the second Temple was destroyed because of sinat chinam, needless hatred -- generally understood to mean not hatred between the Romans and the Jews, but hatred between and among the members of the Jewish people. We haven't grown beyond sinat chinam yet.

I want us to be better than that. I want to be part of a Jewish community where a variety of political viewpoints are not only tolerated but embraced, and where our respect and caring for one another trumps our need to be right. I want to be part of a Jewish community where we can look at our differences honestly, without pretending and without divisive rhetoric -- and, when Shabbat rolls around, collectively set our disagreements aside in order to celebrate together in our varied and various ways. No matter which candidate each of us chooses to support. No matter what our politics around Palestine and Israel.

Im tirzu, ayn zo agadah -- I can only hope that if we will it, it will be no dream.

*(The posts in question are President Lists Anti-Israel Activists Among 'Rabbis for Obama' by Jeff Dunetz, a.k.a. Yid With Lid, and Anti-Israel rabbis for Obama; that same material is now circulating around the rightwing blogosphere, often alongside this Letter from ECI Chairman William Kristol to President Obama.)

For further reading:

Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb is latest target in anti-Obama campaign, Mondoweiss

On the Smear Campaign Against Some Rabbis For Obama by Rabbi Brant Rosen and Rabbi Alissa Wise

Does a good Jew vote for Obama?, Ha'aretz, which features an interview with Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb

If you're attending shul during the Days of Awe...

This is a draft of something I'm hoping to make available at my synagogue during High Holiday services. It's loosely based on something I remember reading when I was an undergrad. I welcome responses, comments, and suggestions. Have you ever tried something like this? What did your version say?

Welcome to High Holiday services at CBI!

Over the course of the Days of Awe, we gather frequently to pray. At most services, we'll experience some of the elements of daily and weekly prayer: psalms of praise and thanks, the Shema and its blessings, the chance to stand before God -- whatever you understand that word to mean, God far above or God deep within -- during the standing prayer called the Amidah. At our morning services we'll read from Torah, as we do every Shabbat.

We'll also experience some things during these services which aren't part of daily and weekly prayer at CBI: a reading from the prophets (called the Haftarah -- this is done weekly at many synagogues, though not at ours), a sermon from the rabbi (which only happens here during the Days of Awe; the rest of the year, if I offer any remarks, they take the short and informal form of a d'var Torah), and a variety of special prayers written for use during the Days of Awe.

It is my deep hope that these services will resonate with you. I hope that the prayers, in their music and in their language, will open something in your heart and in your spirit, and will help you feel connected with God, with our community, and with our tradition at this holy time of year.

But I know that prayer services don't speak to everyone. And these are some of the longest, and most intellectually challenging, services of our year. If you find that our services aren't speaking to you, here are some options. You might:

leaf through the machzor (high holiday prayerbook) in search of pages which resonate with you or interest you -- Torah readings, poems, meditations;

move to the back of our sanctuary and pull a book off of the shelves in our library, which surrounds the big sanctuary -- all of our books relate to Judaism in some way, and who knows, you might pull exactly the book you didn't know you needed to read;

sit in silent meditation and let the service wash over you, taking care to be attentive to your breath and to what arises in you as you listen to the singing and the prayers;

slip outside and experience connection with God through walking in the grass and near the wetlands beside our synagogue, or through sitting in our gazebo; you might try the practice attributed to the Hasidic master Rabbi Nachman of Bratzlav, who had the custom of walking in the fields or in the woods and speaking quietly with God as he went;

find your way to the back of our sanctuary, claim some space for yourself, and do some gentle yoga while you listen to the davening;

visit our classroom, where there is childcare during many of our services, and connect with divinity through spending quality time with the next generation of our community.

This is a unique season in our year, and I want you to experience it wholly. Your shlichei tzibbur (leaders-of-prayer) will do our best to keep our services meaningful and engaging, but if what we're doing isn't speaking to you, we hope you'll forgive us -- and will do whatever you need to do in order to connect with the Days of Awe, with our traditions, and with God.

(Though please don't text or engage with social media in our sanctuary while others are in prayer.)

Wishing you every blessing as we move through this holy season!

Reb Rachel

August 21, 2012

Susannah Dainow's "Fallow"

The envelope was surprisingly small and decorated with stamps. Inside was a copy of a wee chapbook of poems, Fallow by Susannah Dainow. I started reading it with a pile of mail wedged beneath one arm, walking from the post office to my car, and then I sat in the parked car and kept reading until I was done.

These poems are sharp and evocative. Here there are relationships made out of silence and shared choices, a city where even the snow speaks Anglo, sisters who rarely speak, an angry father's fist, illicit sexual thrills turned to blood and rubble, pigeons like grey rats and a murder of crows, moments of insight and memory and sorrow pressed between the pages like dry flowers.

Probably my favorite poem in the collection is "Whalebone Corset." Here is a taste:

I was born asleep, slid

into a corset

of tapestry and whalebone,

invisible to the world, save

for my women -

mother and grandmother pulled and pulled

both sides to tighten me, evening

through the fight, wrench

out one side, then caress,

stretching the other -- I

came to crave the tug, the yank,

the spin-round push-pull as affection...

I especially love the way the poem ends. These are among the most hopeful lines in the collection, for me.

we are

decorseting -- peeling off

the skins and bones, one strip

at a time, we are taking

the echoes of whalesong and building

her back from memory, the record whole

and shaking oceans

An earlier version of this chapbook was a finalist in the 2011 Qarrtsiluni chapbook contest. Susannah Dainow's collection Fallow can be purchased for $14 by emailing the author directly: fallowthechapbook@yahoo.com.

Why I'm a Rabbi For Obama

Four years ago I spent the summer in Jerusalem. When I got home, my shiny new ברק אובמה ("Barack Obama") sticker was waiting for me in my mailbox; it went on my car post haste. I've sported it proudly ever since. Of course, four years ago I wasn't yet a rabbi. Now I am, and I'm delighted to be able to say that I'm part of the renewed Rabbis For Obama. Here's a taste of the press release:

This group of over 613 rabbis - more than double the number of when Rabbis for Obama launched in 2008 – from across the country and across all Jewish denominations recognize that the President has been and will continue to be an advocate and ally on issues important to the American Jewish community...

Why am I a Rabbi for Obama? Because while we don't agree on everything, there's a lot that he's done -- and a lot that he's said -- which is in alignment with who I am and what I believe.

There's the Affordable Care Act, for starters (which OHALAH, my rabbinic association, formally supports.) And he gave a speech in Cairo a few years ago -- about America and Islam, about our responsibilities in an interconnected world, and about the need to move beyond the Palestinian/Israeli stalemate -- which moved me then and still inspires me now. (Here's what I wrote about it then.) He signed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act. He recently denounced Representative Todd Akin's offensive and patently spurious claim that women who suffer "legitimate rape" rarely get pregnant, and spoke out in favor of women being able to make decisions about our own health care and our own bodies. ("Obama: Rape is Rape," Huffington Post.) He signed the Children's Health Insurance Reauthorization Act, which provides health care to 11 million kids -- 4 million of whom were previously uninsured. (see Children's Health Insurance Program info.) He supports stem cell research. (see Obama on Stem Cell Research.) He established the Credit Card Bill of Rights, preventing credit card companies from imposing arbitrary rate increases on customers (see Your Credit Card Bill of Rights Now in Full Effect), and he's making it easier for people to pay back their student loans without bankrupting themselves. (see How President Obama is Helping Lower Monthly Student Loan Payments.) He's got an admirable record on civil rights (see Equal Rights -- President Obama), repealed "Don't Ask Don't Tell" making it possible for GLBT American servicemen and servicewomen to serve our country openly and honestly without fear, signed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Restoration Act, and came out earlier this year in favor of marriage equality. (see Obama Embraces Marriage Equality.) (For more, see WTF Has Obama Done So Far?)

There are things he hasn't managed to accomplish which I had hoped he would do. Actually closing Guantanamo Bay, for instance. (see Guantanamo Bay: How the White House Lost the Fight to Close It, Washington Post.) Brokering a real and lasting two-state peace in Israel/Palestine. (Though the Jewish Journal reports that David Hale, Obama's envoy to the Middle East, continues to pressure Israel, Palestine in peace talks.) But I continue to believe that he is good for this country and that he's working to make the United States, and the world, a better place.

This week's portion: Justice Shall You Pursue

This week we're in parashat Shoftim, late in the book of Dvarim (Deuteronomy.) This parsha is the source of one of the most well-known verses from Torah: "Justice, justice shall you pursue!" In this parsha we read: establish towns where someone who has accidentally committed manslaughter can flee, so that the spiral of violence and retribution doesn't self-perpetuate. We read: do not punish someone on the testimony of a single witness.

We read: on the eve of war, if someone has planted a vineyard but not yet harvested -- built a house but not yet consecrated it -- become engaged but not yet wed -- let that person go home and fulfill those holy promises. (I wrote about that in 2006.) We read: when you approach a town to attack it, offer it terms of peace.

And we also read that if that town refuses the terms of peace, Torah says to attack them and then put all of their men to the sword and enslave their women. And that's only for towns which are far away; for the towns which are nearby, Torah says, the ones containing inhabitants who are known to be idolaters, kill them all. Ouch.

And then we read: even when you are besieging a city, you must not cut down its trees. Are trees human, the Torah asks, that they could flee before you? Therefore show mercy, especially to fruit-bearing trees.

As I study this parsha this year I'm struck by my own oscillation. Some of these verses are beautiful to me, while others make me squirm with discomfort. I don't want such violence to be enshrined in my holy text.

The theme of the parsha, as I understand it, is justice. The cities of refuge are a matter of justice. Releasing young soldiers who haven't yet lived full lives is a matter of justice. Sparing the trees is a matter of justice.

And in the Biblical understanding, the stuff about killing all the men in an enemy city -- or, worse, killing everyone, including the women and children -- is also a matter of justice. But in today's paradigm our understanding of what is just and righteous has shifted. Killing all the enemy men, or slaughtering men and women and children alike, may have been understood as justice in antiquity. Today it would be an unthinkable massacre. I am grateful to live at a moment in time when we understand this kind of violence as horrific.

But violence is still endemic. Earlier this week, the New York Times reported that "scores of Israeli youth" attacked a Palestinian teen named Jamal Julani in Jerusalem, rendering him unconscious and hospitalized. (NYT: Young Israelis Held in Attack on Arabs.) "If it was up to me, I would have murdered him," said one fifteen-year-old boy. Two of the other suspects in the beating are girls, one of them only thirteen years old. (The NYT blog The Lede has more: Account of a 'Lynch' in Jerusalem on Facebook.)

It's enough to make me wish for cities of refuge where people could go to break the cycle of the endless violence. Though in Biblical times, the refuge was only for accidental manslaughter, and it doesn't sound to me like the harm here was inflicted accidentally.

Fortunately Jamal Julani survived the beating. But what is wrong with our world that kids of thirteen and fifteen are swept up in so much hate? What is wrong with our understanding of Torah that we pay more attention to the injunction against cutting down a fruit tree (which is taught each year at Tu BiShvat with great gusto -- see, e.g., the beautiful exhibit "Do Not Destroy: Trees, Art, and Jewish Thought" at the Contemporary Jewish Museum) than to the injunction to pursue justice and righteousness with all our might? (Even fruit trees aren't always safe -- as described in this 2012 Rabbis for Human Rights report about settlers destroying olive groves.)

We've entered the month of Elul, a time for soul-searching and teshuvah. I know I need to make teshuvah for giving in to the inclination to turn away from stories like this one, for closing my eyes to injustice and suffering caused by people who share my religious tradition and my holy text. But Torah does not belong only to those who use it to justify such actions. Torah belongs equally to we who are horrified by these stories.

Tzedek, tzedek tirdof: justice, justice shall you pursue. May we be strengthened in justice and righteousness. May we be brave enough to face injustice and to work toward transformation and healing, here and everywhere.

Recommended reading:

Lynching in Zion Square: Are We Responsible? by Rabbi Jill Jacobs of Rabbis for Human Rights

To-do lists, teshuvah, and whatever gets in the way of the work

I feel this week as though I'm running at a faster clock speed than usual. It's not quite mania, but it's not all that different from it, either. There's a low buzz of anticipation at the base of my spine. When I sit still in silence, a million waves of thought rise up and crash on the rocks of my consciousness. Elul is upon us, and I am vibrating.

Just before Shabbat began last week, I bought a copy of Rae Shagalov's Elul Book as a downloadable pdf, and I showed some of the calligraphy to my congregants on Shabbat morning. Here's the passage which particularly struck me. Here's the text (and a thumbnail which shows part of her calligraphy...)

Wake up from the beautiful dream of the whole year! If you received a court summons in the mail, you would feel a shock of fear. You would call the best lawyers. You would call all your friends and ask for their advice. You would carefully go through all of your accounts to determine the truth of your situation.

It's Elul! Your summons has come in the mail! Feel the shock! Call your lawyers! Call your friends! Go through your accounts today! Determine the truth of your situation! Who are your lawyers? Your mitzvahs. Who are your friends? Your good actions!

Sometimes, a person refuses to wake up. What happens? His friend shakes him awake so he won't be late for an important engagement. We have a choice. We can wake up on our own, early, and prepare ourselves carefully; or we can pull the blanket over our heads, refuse to wake up, and be shaken awake by our greatest friend in the world...

I wish I thought that Elul and its teshuvah work were the only reason I'm feeling a bit busy and buzzy and aswirl. I know this is the month for serious internal work. I know I have only four weeks during which to kick my teshuvah process into gear. But I suspect that another big piece of the reason why I'm feeling so agitated is that there's just so much to do before the Days of Awe begin.

Time to reach out to people who never responded when I offered them honors in our high holiday services. Time to check my high holiday songsheet drafts against the prayerbook to make sure I have the right things on each songsheet. Time to intensify the search for someone willing and able to take ownership of the project of getting our congregational sukkah built. Time to troubleshoot and figure out why the high holiday cds we burned for our entire congregation won't play on a cd player, and only half of the tracks will play in my car. Time to, time to, time to --

And at the same time, there's a part of my brain which whispers: time to wake up. Time to take a good hard look at my life. Time to discern, where do I habitually miss the mark? How can I become a better version of myself? What are the places where I'm spiritually lazy? Only four weeks now to prepare myself to attempt to lead my community in prayer, to stand before the King of Kings in God's own throne room, to make something meaningful for those who join us in prayer, and how can I do any of those things if I haven't also done my own teshuvah?

This is my second year as a congregational rabbi, and I'm still figuring out how to balance all of this. I feel as though my own internal work has to take a backseat until the congregational logistics are under control -- and yet if I don't do my own internal work, I won't be able to lead the congregation in the way that they deserve.

Whatever gets in the way of the work, is the work. I learned that from the poet Jason Shinder, of blessed memory. Can I find a way to tackle the congregational pre-high-holiday to-do list which will allow me to live out the teshuvah, the repentance and return, that I know I need? Can I make phone calls, send emails, generate revised to-do lists with prayerful consciousness? I've said for years that my challenge is figuring out how to live out my spiritual aspirations not when I'm on retreat, not when I'm on a break from ordinary life, but precisely in and through my ordinary life. Not separation, but integration. Here's another opportunity to (try to) do just that.

Here it is, Elul again at last, the scant four weeks between now and Rosh Hashanah dwindling by the minute. Can I trust that what I'm doing is what I'm meant to be doing? That everything will get done, somehow, some way? That I can make teshuvah not when I'm done with the work at hand, but even as I do the work which needs to be done?

August 20, 2012

Resources for Elul

We've recently entered into the month of Elul, the lunar month leading up to the Days of Awe.

The name Elul can be read as an acronym for Ani L'dodi V'dodi Li -- "I am my Beloved's and my Beloved is mine." (Song of Songs.) This is the month when we're encouraged to relate to God as the divine Beloved; to walk in the fields with God as one might walk with a lover, speaking intimately one-to-one.

Here are a few resources for the lunar month we've just begun:

My Prayer for Elul by Rabbi Brant Rosen, posted at his spirituality-focused blog Yedid Nefesh. This is his own interpretation of psalm 27, traditionally read every day during this month.

Or, for an alternative, here's poet Alicia Ostriker's poetic rendering of psalm 27. Another practice is to sing Achat Sha'alti (One Thing I Ask) every day, which is a setting of part of that psalm.

Your First Step Begins the Journey by Jueli Garfinkle at Moon Over Maui. Jueli provides a lovely printable calendar which one can use to concretize a commitment to making this month a spiritually-meaningful time of year.

Speaking of lovely and printable, I just bought a copy of this Elul Book, a downloadable pdf of Rae Shagalov's calligraphic Torah teachings about teshuvah and the month of Elul. It's beautiful calligraphy and each page is packed with teachings and insights. You can preview each page of the book on the Holy Sparks website, and you can buy individual prints if you don't want the whole thing.

Relating to God in Elul, On Rosh Hashanah, and On Yom Kippur, a seven-part essay by R' Yitzchak Ginsburgh. Occasionally a bit esoteric, but there's some beautiful material here. The section on Returning to God in Elul is particularly interesting to me.

Riding With the King, my own post about Elul from 2008, which explores a couple of different Hasidic folktales and interpretations of what this holy month is all about.

May your Elul be meaningful and sweet!

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers