Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 211

September 28, 2012

Days of Awe 5773: a baker's dozen of moments to remember

Sitting down with my family -- parents, in-laws, husband, sister, nephew, son -- for an early Erev Rosh Hashanah dinner. Fabulous food, good conversation, pumpkin panna cotta with hazelnut brittle, and most of all, the joy of seeing my far-flung family gathered around our dining room table again.

Sitting down with my family -- parents, in-laws, husband, sister, nephew, son -- for an early Erev Rosh Hashanah dinner. Fabulous food, good conversation, pumpkin panna cotta with hazelnut brittle, and most of all, the joy of seeing my far-flung family gathered around our dining room table again.My friend and colleague David Curiel, our cantorial soloist for this year, teaching my community a three-part Ilu Finu melody (find it online here or here) on the first morning of Rosh Hashanah, and hearing my community enthusiastically singing along. The way the harmony rippled like sunlight on water.

Walking to the river for Tashlich, holding a young man's hand and talking about his lego creations all the way there. Tossing matzah into the river and thinking with each bit I threw about something I wanted to let go of, a place where I'd missed the mark in the year which just ended.

The impromptu pedicure my mom treated me to, after second-day Rosh Hashanah services were concluded. An unexpected gift. And oh, getting gently pummeled by the massaging spa chair felt so good!

Picking apples with my husband and son on the Sunday between the holidays. Drew knew apples, and he knew trees, but he never knew apples grew on trees! His glee at being able to pick apples himself. The sweetness of honeycrisps fresh off the tree. His proclamation that apples are his favorite fruit.

Leading a dear friend and her family through the process of taharah, in the family home, on the day which would become Yom Kippur. The love present in that room. The mikveh of tears. How putting on my white linen garb before Kol Nidre reminded me viscerally of the white linen shroud I had unfolded only a few hours before.

Singing "Oh Jonah, he lived in a whale! Oh Jonah, he lived in a whale! He made his home in that fish's abdomen, oh, Jonah, he lived in a whale" in my very best sultry Gershwin style before my Yom Kippur morning sermon on Jonah. The ripple of laughter, and how it transmuted into rapt attention.

Going beneath my tallit during the silent prayers of Yizkor to engage in what my teacher Reb Zalman calls a "holy Skype call" with the spirits of my beloved dead. I talked to my grandparents, who I loved and who I miss. To our dear friend Dick, who I loved and who I miss. I told them what I needed to tell them. I imagined them right there in front of me, beaming at me.

Settling into afternoon yoga with Bernice Lewis, who leads such a loving and gentle yoga class. Rediscovering what I had forgotten since last year: that perhaps the sweetest gift of that yoga time is relaxing into letting someone else take care of me on Yom Kippur afternoon. Child's pose, and how it reminded me of the prostration of the Great Aleinu.

The amazing Avodah meditation led by David. The low hum of the sruti box. The way he brought the story of the rituals performed by the high priest once upon a time into right-here, right-now. His sweet chant of Ana B'Koach in place of every time the Great Name -- whose ancient pronunciation is, these days, lost to us -- arose. His teaching that every place can be the holy of holies, every person can be the high priest, every moment can be the holiest moment.

Bob blowing that one final tekiah gedolah. The long arc of the sound, the way it seems to tunnel right inside me, reaching that most profound place. The intermingled sadness and relief when it was over: the shofar blast, the holiday, the Days of Awe, all come to their inevitable end.

Breaking my fast with that nip of ice-cold vodka, as my grandfather Eppie -- may his memory be a blessing -- always used to do. The cold fire of it going down, the flush it brought to our faces, the laughter. The knowledge that people in my community who weren't blessed to know Eppie were thinking of him in that moment, if only because I was thinking of him, and that in this way, he is still here, still with me.

The gift I received from one of my dear congregants, one of the older fellows in our community, when he came up to David and me at the break-the-fast and told us that our services on this day allowed him to really understand the prayers, and made him happy to be Jewish. What more could I hope for? I feel so blessed.

September 27, 2012

A poem after the High Holidays

I empty the mother jar

measure flour and water

drape a dishtowel tallit

unearth one wilted celery

and a faded fennel bulb,

today's wholeness offering

soon diced onion hisses

sibilant in the skillet

glistening in chicken fat

this is how I return

after days of aching ankles

heart cracked open from overuse

how can I cook

when I'm faded as grass

and empty as a shofar?

I turn old roots

and sorrow's salt into

soup fragrant as havdalah

the freezer yields

what it's been withholding

I invent the new year as I go

the humblest ingredients

turn silky and transcendent

after this long slow simmer

I began writing this poem right after Rosh Hashanah, and posted an earlier draft here -- After Rosh Hashanah. Here's the current version -- a slightly different shape, a new ending, a few revisions here and there. I think this version is better, though I'm curious to hear what y'all think. Maybe I needed to make it through both of the High Holidays before I could discern what this poem really wanted to be.

As always, I welcome feedback of all sorts.

Two poems in em:me

It's a delight to see two of my mother poems in the current issue of em:me, "an online journal of poetry, visual art, and cross-genre creations" published seasonally and edited by Emmalea Russo.

It's a delight to see two of my mother poems in the current issue of em:me, "an online journal of poetry, visual art, and cross-genre creations" published seasonally and edited by Emmalea Russo.

The magazine is beautifully put-together, easily readable online, and full of interesting and poignant work. I especially like Kristi Nimmo's poem and Graham Hunter Gregg's poem, the film stills by Daniel Paashaus, and Emma Horning's photographs. It's neat to read my own poems in the context of this journal.

Read the issue here: em:me issue 3, fall 2012. Thanks for including them, Emmalea! I'm already looking forward to reading issue 4 when the winter solstice rolls around.

A Sukkot prayer for the Bedouin at Rabbis for Human Rights

Hope all of y'all had a wonderful Yom Kippur!

Earlier this summer the folks at Rabbis for Human Rights North America asked if I would write a Sukkot prayer which touches on the situation of the Israeli Bedouin. I was honored to be asked, and took on the task with some trepidation; I hope the result is meaningful.

Here's how my prayer begins:

Ribbono Shel Olam, Master of the Universe --

Shekhinah, Whose wings shelter creation --

Once our people wandered the desert sands.

Now we merely vacation in rootlessness

While our Bedouin neighbors perch

Without permission, their goats forbidden to graze.

Time after time the bulldozers tear down homes

And playgrounds, uprooting spindly olive trees

To make room for someone else's future forest,

As though saplings mattered more than children...

You can find the whole prayer on the RHR-NA website, in the Sukkot section -- A Sukkot Prayer for the Bedouin -- or in the Prayers section (Prayers | A Sukkot Prayer for the Bedouin) where the prayer appears alongside an image of, as it happens, me in prayer during the last Rabbis for Human Rights conference I was blessed to attend.

Sukkot begins on Sunday at sundown. May this prayer help us to remain mindful of the Bedouin and their situation even as we celebrate Sukkot, the season of our rejoicing. Stay tuned -- I'll share more Bedouin resources from RHR once they're online.

September 26, 2012

A sermon for Yom Kippur Morning: In The Belly of the Whale

This is the sermon I offered this morning at my synagogue.

Once there was a man named Jonah, "Dove," son of Amittai, "Truth."

And God spoke to him and said, Go to the great city of Nineveh and tell them to make teshuvah, otherwise I will destroy them for their wickedness. And in response, Jonah fled.

This is a familiar story. We'll read it again this afternoon during mincha, and we'll look at some fascinating modern commentaries during our Torah study afterwards. But I want to lift up a few details now, because some of you may not return for mincha, and there's something powerful about encountering this particular story on this particular day of the year.

Jonah flees from God, onto a ship bound for Tarshish. He heads in precisely the direction God didn't tell him to go. An actual Wrong-Way Corrigan. Does he really think he can escape from the Holy Blessed One, the King of Kings, Who can see him anywhere he goes?

My teacher Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi tells a Sufi story about a great teacher whose disciples wanted to learn his mystical wisdom. Okay, said the teacher; here is a dove; go someplace where no one can see you, and kill it, and when you come back, I will teach you what you want to know.

Of his 12 students, eleven came back with dead birds, and he sent them away. One returned with the living dove. "I couldn't find a place," said the student, "where no One could see me." It was to that student, who understood God's omnipresence, that the teacher chose to transmit his blessing and his wisdom.

But our Jonah, our dove, forgets that. He flies from his calling, flees from God.

Once his ship is at sea, a mighty storm arises. The sailors are in a panic. And Jonah is sound asleep belowdecks. This is comedy. Imagine the ship rocking wildly from side to side, sloshing with seawater and in danger of foundering: and our hero, or perhaps our anti-hero, is sound asleep!

It's also a deep spiritual teaching. How often, in our lives, do we hide from what we know we're meant to be doing? How often are we spiritually asleep?

In her book The Murmuring Deep: Reflections on the Biblical Unconscious, Avivah Zornberg writes beautifully about this moment. She quotes the midrash, Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer: "The captain of the ship came to him and said, 'Behold, we are standing between death and life, and you are sound asleep!'" And here's Zornberg:

The captain expresses the existential plight of those who stand between death and life. Uneasily straddling death and life, the sailors stand and cry. Jonah escapes into a stupefied sleep.

Here, the midrash registers the core of Jonah's flight. To flee from God is to refuse to stand between death and life; it is to refuse to cry out from that standing place. The opposite of flight from God is, in a word, prayer.

The opposite of flight from God is, in a word, prayer.

Jewish morning prayer has a trajectory. We begin with blessings for waking and for the miracles of each day: that's the realm of the body. We ascend into the realm of the heart with psalms of praise. We ascend into the realm of consciousness with the Shema. And then we ascend to the highest peak, the place where we stand before God, with the amidah, the prayer whose name means "standing."

Standing isn't merely a matter of choreography. It's an existential truth. When we pray, we are called to stand before God, whatever we understand God to mean: God far above or deep within, our highest aspirations, the One Who set the Big Bang in motion, the source of love and compassion in the universe. We're called to be wholly present.

The opposite of prayer, says Zornberg, is flight. Fleeing from our responsibilities. Fleeing from God. Fleeing from whatever calls us to be better people, to improve ourselves, to be good to others, to choose mercy and kindness over strict justice.

How much of our lives do we spend fleeing from what matters? From the awareness of our mortality? From the acts of lovingkindness we know we should be doing? From the brokenness of the world, the awful stories on the news, murder and rape and injustice? Even from our loved ones, when we choose checking email again on our smartphones rather than putting away the electronics and connecting with our parents, our children, ourselves?

This is not new. The internet offers new and fascinating ways of fleeing, but this inclination is as old as humanity. We see this in the Psalms -- both the desire to flee, and the realization that flight is inevitably impossible. Here's a taste of psalm 139:

Where can I escape from Your spirit?

Where can I flee from Your presence?

If I ascend to heaven, You are there;

If I descend to Sheol, You are there too...

It was You who created my kidneys;

You fashioned me in my mother's womb.

I praise You,

For I am fearfully, wondrously made.

Notice how the psalm moves from anxiety -- "where can I escape from Your spirit?"-- to praise: "You fashioned me in my mother's womb; I praise You." Today offers us an opportunity to make that same leap.

In the belly of the great fish, Jonah offers a monologue which sounds very like a psalm. Jonah's first prayer comes when he has reached rock-bottom: he goes down to the harbor, goes down into the belly of the ship, goes down into the sea, goes down into the belly of the whale. It is only from those depths that he is able to pray.

We, too, are often moved to our deepest prayers in moments of crisis and brokenness. Sometimes it's hard to make the time for standing-before-God when life is good. But when we're at the bottom of the sea? They say there are no atheists in foxholes; and though that can't be true, it is human nature to cry out when times are tough. "From the depths, I call to You, O God!" (Psalm 130:1)

Midrash offers a fascinating window into Jonah's experience inside the whale. In Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, written in the early first century C.E., we read that Jonah entered the mouth of the whale as we enter the doors of a synagogue. Light streamed in through the whale's eyes, like the windows of a synagogue. Jonah approached the bimah, the whale's head. And Jonah said to the whale, show me the wonders of creation.

So the great fish took Jonah on a tour of the deeps. He showed Jonah the Foundation Stone of the Temple, fixed in the depths of the sea below the land. (Our ancestors believed that our lands rested atop primordial chaotic waters.) And the fish said to Jonah, you are standing beneath God's temple; you should pray. And Jonah said to the fish: "stand in your standing place; I want to pray."

Stand in your standing place. Jonah asks the fish to help him do what he has been unable to do: to stand before God. Again, this isn't literal, it's existential. Stand, sit, lie down, swim: but be present. You have to be wholly present in order to pray.

The funny thing is, when he finally offers a prayer, Jonah doesn't use his own words. In the midrash, Jonah quotes from Hannah's song of gratitude, which she speaks when her prayer for a child is answered. In the book of Jonah itself, Jonah's "psalm" from the belly of the whale is deeply derivative; it sounds like bits of many different psalms stitched together. His prayer is pastiche. It's a collage of other peoples' words.

We are all Jonah. We are all prone to fleeing from the things we don't want to face, the truths we don't want to own up to, the work in the world we don't want to have to do. Here we are in the belly of this great whale, the windows of our sanctuary offering eyes for looking out on the world. Together we are transported, this morning, into someplace deep and strange.

We too pray using other peoples' words. The words of our Torah, the words of our sages, the words of our tradition. And let me be clear: I love these words dearly. But how do we invest them with the meaning we need?

How can we graft our inchoate cry into these borrowed words? Can we pray them with authenticity? What is it that we yearn for, as we crest the wave of this Yom Kippur and prepare to dive into the depths of our own seas?

I can tell you what I yearn for. I yearn for connection. I yearn to be truly seen, in the fullness of who I am, and to be loved not despite that fullness but in and through it. I yearn to be held. I yearn to be heard.

I yearn for a world healed of trauma. A world in which people of all genders, of all races, of all religions and none, are safe. A world in which no child need ever fear abuse.

I yearn to live up to the best of who I can be. To be kind and compassionate, always, and to receive kindness and compassion in return. I yearn to be a good person, a good spouse, a good child, a good mother. A good rabbi.

I yearn to be grateful. I yearn to experience the full range of my emotions, from joy to sorrow, without numbing myself either to what hurts me or to what heals me.

Yom Kippur offers us the opportunity to face ourselves and to seek what we most yearn for. On this day, connection: the sages tell us that today God is most near to us. On this day, we are truly seen, and truly loved, in all that we are. Even our failings. Even our fears.

And on this day, we have work to do. Today we reconsecrate ourselves to the task of healing the world from its brokenness.

Why does Jonah run from God? Because he knows that once he goes to Nineveh and preaches teshuvah, the people will repent and God will forgive. And they do, and God does, and Jonah is furious. Sometimes it's hard to let go of our childlike fantasies of a world of simple equations, where those who do good are rewarded and those who do evil are struck down.

Jonah says, I am so angry I want to die! And God says, "Hmm, are you really angry?" Zornberg sees this as a therapeutic question. I see it as a parental one.

What would happen to us if we let go of our anger? If we let go of our need to be right? If we acted out of mercy, not the desire for vindication? Maybe then we would be less like Jonah, and more like God. Less like a cranky toddler, and more like a beneficent parent.

Here we stand in the belly of the whale. God is calling us to awareness, to stand before God in the place where we are, to do the work that needs doing in the world. To bring healing, to bring mercy, to bring kindness even to those who are unlike us.

Are we listening?

Kol Nidre Sermon: What Are We Here For?

Once there was a great rabbi named Yekhiel. Reb Yekhiel could discern the deepest truths in a person's soul just by looking at them. He would gaze at your forehead for a moment, and then tell you the history of your soul in all of its incarnations.

Some people sought him out, wanting to know who they had been before. Others avoided him. Some would pull their hats down over their faces to try to hide from him. Which was ridiculous, because surely a man who can gaze into the history of your soul just by looking at you can also gaze through a bit of leather or cloth!

It was said that Reb Yekhiel turned every day into Yom Kippur. In a good way! Because he was able to see into the depths of people's souls, and help them understand where they had gone wrong, and how to correct their mistakes in this life.

One year, on the eve of Rosh Hashanah, Reb Yekhiel saw an apparition. He recognized the man immediately: it was the cantor who used to chant so beautifully in Reb Yekhiel's hometown. "What are you doing here?" asked Reb Yekhiel.

"Surely the holy rabbi already knows," replied the soul of the hazzan. "On Rosh Hashanah, God opens the Book of Life. With every deed, we inscribe ourselves in that book. God looks at our sins and our good deeds, and weighs them both in the balance. Who shall live and who shall die? Who shall be born -- and to which family? During this night, souls are also judged to be reincarnated once again. I am just such a soul, about to be reborn."

"So tell me," the rabbi asked, "why are you being sent down into the physical world again?"

"The Zohar," said the ghost of the hazzan, "teaches that when God desires to take back a person's spirit, all the deeds that person did pass before them. And that's what happened to me. I looked back on my life and everything I had done was good. When I realized this, I felt tremendous pride! And in that moment, I died. Because of my ego and my pride, the Heavenly Court decreed that I should return to earth."

Not long thereafter, Reb Yekhiel's wife gave birth to a son. They named him Zev-Wolf. He was wild and willful. Perhaps he was a bit impish; perhaps he threw temper tantrums when he couldn't have yogurt pretzels for breakfast; surely he had a good heart.

Reb Yekhiel knew that this was the soul he had seen on Rosh Hashanah night, and that his son's rebellious ways were connected to the sin of pride which had caused him to reincarnate in the first place. But Zev did not remember.

As wild young Zev neared bar mitzvah, his father commissioned a set of tefillin for him. But he asked the scribe to bring him the little black boxes which would hold the parchments, so that he could pray over them before the scrolls went inside. He took the empty boxes, and as he thought about his beloved son, and about his baggage from his previous life, he began to weep. He wept his prayers and his love and his caring into the boxes. Then he carefully dried them and put the scrolls inside.

From the moment Zev-Wolf put on those holy tefillin, a spiritual transformation came over him. His rebelliousness left him, and he became filled with tranquility and love. Eventually he became a great Hasidic Rebbe, Zev-Wolf of Zbarash, and he is remembered for his deep humility to this day.

I love this Hasidic folktale. And not only because I myself have a beautiful, willful, stubborn son!

When you think about reincarnation, what do you imagine? Maybe your mind goes to Eastern religious traditions. Many Buddhist parables speak of reincarnation, and most of us associate the notion of karma, the impact of our volitional actions which can reach across lifetimes, with Buddhism. But these ideas exist within Judaism, too.

In the oldest forms of Judaism we find belief in the resurrection of the dead. There are frequent references to resurrection in our prayers: the Amidah, for instance, praises God as m'chayyei ha-meitim, "Who gives life to the dead."

In the early Reform movement, and in the Reconstructionist movement, this was regarded as too supernatural, too far-fetched. Some siddurim changed the words to "Who gives life to all." Others subtly shifted their understanding of the words: perhaps we praise not God Who enlivens the dead, but God Who enlivens the deadened.

When my son was a few months old and I accepted that what I was suffering was postpartum depression, I began taking antidepressants. The blessing I made over those pills was this same m'chayyei ha-meitim. I prayed for God to enliven that in me which felt deadened. And Baruch Hashem! God did.

But there are other ways of thinking about resurrection in Jewish tradition. One school of thought holds that resurrection is not a one-time event, but an ongoing process. The souls of the righteous are reborn into this world to continue the ongoing process of tikkun olam, healing what is broken in creation.

Some sources hold that reincarnation is routine; others argue that it only occurs in unusual circumstances, such as when a soul leaves unfinished business behind. (The Hasidic folktale I offered a few moments ago takes that latter stance.) One teaching holds that we are each reincarnated enough times to fulfil each of the 613 mitzvot! Reincarnation is one way to explain the traditional belief that we were all present at Sinai when we entered into covenant with God.

Here is a prayer which sits on my bedside table. This is part of the most traditional bedtime Shema liturgy; the translation is by R' Zalman Schachter-Shalomi.

Bedtime Prayer of Forgiveness

You, My Eternal Friend,

Witness that I forgive anyone

who hurt or upset me or offended me -

damaging my body, my property,

my reputation or people that I love;

whether by accident or willfully,

carelessly or purposely,

with words, deeds, thought, or attitudes;

in this lifetime or another incarnation -

I forgive every person,

May no one be punished because of me.

Help me, Eternal Friend,

to keep from offending You and others.

Help me to be thoughtful

and not commit outrage,

by doing what is evil in Your eyes.

Whatever sins I have committed,

blot out please, in Your abundant kindness

and spare me suffering or harmful illnesses.

Hear the words of my mouth and

may the meditations of my heart

find acceptance before You, Eternal Friend

Who protects and frees me. Amen.

I don't manage to say these words every night, but I try to. And I try to mean them.

If I can think back on my day, and honestly let go of whatever baggage I am carrying -- that guy who cut me off in traffic, that woman who sent me an angry email, that thing which angered me -- then I can go to sleep feeling lighter, without karmic baggage. It's like the old adage about not going to bed mad.

And if I should die before I wake, I've made my peace with my actions and the actions of others. And if I should live until morning, as please God I hope to do, then I can wake with a clean slate.

Yom Kippur is a rehearsal for the day of our deaths. Today we wear white, like our burial shrouds. (Some wear a white robe called a kittel, in which they will someday be buried.) Today we abstain from food and drink; the dead need neither. And today we say the vidui, the confessional prayers, as we will say on our deathbeds. As Rabbi Shef Gold has written, "For the whole day of Yom Kippur, we act as if it is our last day, our only day to face the Truth, forgive ourselves and each other, remember who we are and why we were born."

Today is our chance to release all the karmic baggage we haven't managed to let go in the last year. To set ourselves, and everyone we know, free. Not so that we can die at peace -- but so that we can live at peace, with ourselves and with one another.

Rambam, the great medieval philospher and synthesizer of Jewish law, had a great deal to teach about teshuvah. He wrote that teshuvah is only complete when we find ourselves in exactly the same position we were in when we went wrong before, and we make a different choice.

The objection was raised: what happens if the circumstances don't repeat themselves? What if I can't make full teshuvah because I never get the chance to re-do that act, those words, that choice?

But Rambam said, ahh, Heraclitus was wrong: you can step into the same river twice. Indeed, we all do, all the time. Teshuvah is possible because we are always returning to the same circumstances in which we previously went wrong.

Rabbi Alan Lew writes,

The unresolved elements of our lives -- the unconscious patterns, the conflicts and problems that seem to arise no matter where we go or with whom we find ourselves -- continue to pull us into the same moral and spiritual circumstances over and over again until we figure out how to resolve them.

Spiritually we are called to responsibility, to ask, What am I doing to make this recur again and again? Even if it is a conflict that was clearly thrust upon me from the outside, how am I plugging in to it, what is there in me that needs to be engaged in this conflict?

We are always slipping into alienation and estrangement. From God, from our parents, from our children, from what we love, from the source of meaning in our lives. And it is always possible to make the shift of teshuvah, and to make a different choice.

Rambam was a rationalist, not a mystic. But I think it's possible to read his teachings on teshuvah through the lens of gilgul, reincarnation, the "transmigration of souls." Perhaps one of the ways in which we bring ourselves back to the same circumstances time and again is through reincarnation. Maybe the mistake I keep making in this lifetime is one I've made before, and only when I stop making this mistake will I be ready for whatever's next.

What do you think your soul might be here to learn, this time around? What is the work you are uniquely here on earth to do? What are you here for?

And now that you are here: what is the karma that you create with your actions, your words, your choices? Our liturgy tells us that we write the book of our own life with every action we take. What kind of book are you writing?

There's a teaching in Talmud that "One who doesn't build the Beit HaMikdash in their own time, it's as though they themselves had destroyed it." If we don't rebuild the Temple, it's as though we had been the ones who tore it down. Pretty harsh stuff.

But the Hasidic rabbi known as the Bnei Yissachar offers a beautiful way of re-reading that teaching. He says, that Talmud passage is talking about someone who doesn't know what Torah they're uniquely meant to learn and to teach. Such a one, he says, is as though they had destroyed the Temple in Jerusalem. But one who figures out what Torah they're meant to learn and to teach, that one contributes to the cosmic rebuilding: not with bricks and mortar, but with heart and soul.

Torah can mean not only the Five Books of Moses; not only the depth and breadth of Jewish text and tradition; but also the embodied Torah of human experience.

What is the Torah of your life which you are meant to learn and to teach?

What is it that you want your heart and soul to help build?

What are you here for?

September 25, 2012

The most amazing lead-up to Yom Kippur

On Monday morning the phone rang. The caller ID showed an unfamiliar number, but something told me I should pick it up. It was a dear friend, calling from a borrowed number. Her parent had just died. After I offered what comfort I could, she asked for my help. As the day unfolded, it became clear to both of us how I could be of service.

This morning -- the day which would become Yom Kippur -- I dropped my son off at preschool and then drove over the mountains. I met my friend there, and embraced her, and embraced the family. In their living room, overlooking beautiful woods and hills, I explained the traditional process of taharah, the bathing and blessing and dressing of the body of someone who has died. (See Facing Impermanence, 2005.) I explained the process as I have learned it, and I explained how we would make it work today here in this private home.

Ordinarily it is the chevra kadisha, the volunteer burial society, who lovingly prepare the body of someone who has died. In my experience, this is done at a local funeral home. In my town we don't have a Jewish funeral home, but we have a very friendly non-Jewish funeral home where the proprietors know our customs and welcome us into their space for this holy work. I suspect the same is true in the Pioneer Valley where I spent this morning. And the local chevra kadisha had offered to provide this service at the funeral home they work with...but the family wanted to do it themselves, at home.

Most sources indicate that family members do not participate in taharah because it would be too difficult, too painful. But this family yearned to do taharah themselves, there in the serene home where their loved one had died and had been kept company ever since. In our chevra kadisha, we have permitted family participation from time to time. When someone feels the deep need to care for their loved one in this way, we do not say no. Particularly in a case where a spouse or child has been caring physically for a loved one during illness, sometimes they need to tenderly offer this one last touch in order to say goodbye.

My friend's family didn't want to involve a funeral home or to enter the impersonal space of whatever room the local chevra kadisha uses for this process, and they didn't want to entrust their loved one to strangers, even the nicest of strangers. So together we centered ourselves, and went up the curving wooden stairs to the bedroom.

We said prayers to prepare ourselves. We spoke to the meit, the body of the person who had died, asking the neshamah -- the soul -- to forgive us if we happened to do anything improper or to offend in any way. Moving slowly and gently we washed the meit clean with washcloths, which we dipped into a beautiful ceramic bowl of warm water. My friend wept, from time to time. We offered one another words of comfort as needed.

We poured a stream of water, our symbolic mikveh, as I spoke the words which remind us that the soul is pure. And then we gently dried and dresssed the body in tachrichim, the white linen shroud in which every Jew is buried. Rich or poor, male or female, we are all alike in the end. Slowly the transformation took place: from the shell of a human body which had contained life to a white-bundled figure, arms and legs and head and torso all covered in white.

The last step was swaddling in a white linen sheet -- like the way parents swaddle newborns, I said, and my friend laughed through her tears, remembering my newborn son and how he would only sleep if swaddled (and sometimes not even then!) With the help of a few local friends, the meit was placed in the beautiful simple pine coffin -- handmade, sanded smooth as silk. A bit of earth from the home garden was sprinkled inside, a connection to the soil in which this beloved soul had thrived.

I left that home feeling lighter than I had when I'd entered. Feeling centered and connected. Feeling connected to my friend and her family -- to my own family -- to all the generations of my ancestry, and to my son and the generations I hope will follow -- most of all to God.

Yom Kippur can be understood as a day of rehearsal for one's own death. We wear white, like the shrouds in which we will be buried. We eschew food and drink, as we will do when our physical lives have ended. We recite a vidui prayer very like the one recited on the deathbed.

On Yom Kippur we try as hard as we can to make teshuvah, to correct our course and shift our alignment so that our actions, our emotions, our thoughts, and our spirits are aligned with holiness. We try to repair our relationships with ourselves, with each other, with God. We try to relinquish the emotional and spiritual calluses which protect us in ordinary life, and to go deep into awareness of our mortality and deep into connection with something beyond ourselves.

I can't think of any better way to prepare myself for the awesome task of leading my community in prayer throughout Yom Kippur than what I was blessed to do this morning. When I don my all-white linen garb tonight, I will remember the feeling of these tachrichim beneath my fingers this morning. When I invite my community to join me in experiencing this holiday as a reminder of our mortality, I will think of this family and their encounter with death.

And when I lead us in davenen tonight and tomorrow, I will do so in the hope that our prayers will rise to the Holy Blessed One as do the prayers of these mourners, and that God will grant compassion and healing to them and to us. Kein yehi ratzon -- may it be so.

One last post before Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur is fast approaching.

Tonight my community will gather around 5:40 to hear a pianist and violinist playing Kol Nidre and other appropriate melodies; on the dot of 6, we'll move into our recitations of Kol Nidre and into our communal observance of this tremendous, awesome, holy day.

Here are links to two posts I've made in previous years, each of which is a compilation of Yom Kippur materials: prayers, divrei Torah, YouTube videos, sermons, practices, translations, sheet music, poems, readings, liturgy, song, teachings, all kinds of good stuff:

Grab-bag of resources for Yom Kippur, 2006.

More Yom Kippur resources, 2010.

I hope that all who need inspiration will find something meaningful among those pages.

If I have hurt or offended you in any way in the last year, please forgive me.

G'mar chatimah tovah -- may we all be sealed for good in the year to come.

September 23, 2012

A havdalah ritual for the September equinox

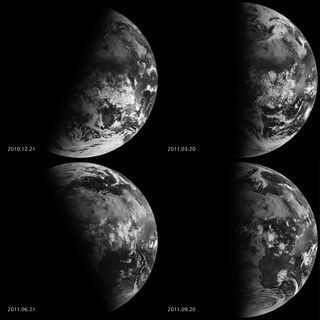

Equinox and solstice photo courtesy of NASA.

The September equinox was yesterday.

Back at the end of June, I was blessed to celebrate Rosh Chodesh (new moon) with the women of my congregation, and this past June, the start of Tammuz fell right around the time of the June solstice -- what is, in our hemisphere, the summer solstice, the longest day of the year. We celebrated with a havdalah ritual for the turn of the seasons, and it was wondrous.

Ever since then, I've been meaning to create a similar ritual for the fall equinox. And I did create one! I just didn't manage to post it in advance. (Please forgive me. Life's been a bit hectic around here lately.) Enclosed with this post is a havdalah ritual which marks and sanctifies the division between summer and fall.

What's the use of posting such a ritual after the equinox has passed? Well -- some sources indicate that while 9/22 is the equinox, the day when we will actually experience equal hours of daylight and darkness is Tuesday. So I think there is meaning in observing this special havdalah anytime between now and Tuesday, anytime between now and Yom Kippur.

Deep thanks to Rabbi Jill Hammer, whose Tishrei wisdom at Tel Shemesh provided much of the inspiration for this havdalah!

Download FallEquinoxHavdalah [pdf]

September 22, 2012

First day of fall

Leaves under water. Margaret Lindley Pond, Williamstown.

First day of fall. The hillsides' green has shifted, yellow beginning to reveal itself as chlorophyll starts to hide away. I think of John Jerome's Stone Work, of how he wrote about yellow leaves falling, about the old year becoming mulch.

After the rush and flurry of September -- the start of the Hebrew school year, the first Family Shabbat service, Drew starting preschool, the spiritual work of leading two days' worth of Rosh Hashanah services -- it feels strange and wondrous to have a weekend off. Ethan takes Drew to Caretaker Farm; I stay home with a cup of coffee, eat challah with honey, knead bread dough, get the dishwasher running.

It's time to begin moving the summer clothes back into the attic and bringing the fall wardrobe back out again. In the span of a week we've moved from weather which makes me want sandals and flowing linen to weather which makes me want bluejeans and layers, socks and closed-toed shoes.

I love summer. I was born and reared in south Texas; I bask in the heat. And every year I brace myself against the darkening of the days. In high summer I think: how will I ever survive when the sun goes down at 4:30 in the afternoon? It seems inconceivable that we will spend so much of the year in the cold and the dark.

But then the Days of Awe roll around, and the leaves start to turn, and I realize I have missed autumn. I'd forgotten how beautiful it is to watch the mountains' slow color-shifting dance. I'd forgotten the appeal of cozy sweaters, of patterned tights, of Sundays watching football, of pumpkins brightening our doorsteps.

It's not cold enough yet for the real winter wear -- the fleece-lined jeans, the heavy wool sweaters. They still seem as implausible as armor, so they stay in their boxes...for now. But the summer clothes go into the attic, armload by armload, and the autumn clothes emerge. By the end of the morning I am sniffling like mad, my allergies reawakened by the inevitable encounter with our household's particular brand of dust.

But my closet is transformed. Gone are the flowy bright skirts and tanktops, replaced with velvet and corduroy and denim. I remember again how much I gravitate toward brown and purple at this time of year -- a mirroring of the colors our hillsides will take on once the leaves have offered their final farewell.

We move through so many gates, so many doorways, at this time of year. From summer into fall; from the old year into the new; from anticipation into celebration; from the light half of the year to the dark half of the year. What will be nurtured and nourished in us during the season now beginning? What gifts will the velvety darkness of fall and winter offer this year? What qualities will I clothe myself in as the new season unfolds?

For an explanation of the equinox, including a truly gorgeous photograph of the earth seen from space at both equinoxes and both solstices, try Autumnal equinox: Equal Hours of Daylight and Darkness? Or Not?

You might also enjoy the poem I posted a few years ago on the autumn equinox, titled, appropriately, Equinox.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers