Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 212

September 21, 2012

Notes from Shabbat Shuvah at Elat Chayyim, fall 2003 / 5764

Elat Chayyim is every bit as fantastic as I remembered. When I arrived on Friday, I had this feeling of, "It's real! It's really here! I didn't make it up!" I walked around like I was in a dream.

The first thing we did on Friday night was daven the evening prayers, and I was transported. I really, really like the way they think about prayer here. I like the melodies, I like how easy they are to learn, I like that the focus is on saying fewer words with kavanah (intent) rather than saying lots of words. I like their approach to God-language. I like how prayer services become a vehicle for learning new things.

Saturday's classes were with Rabbi Miles Krassen. We studied a text by R' Schneur Zalman of Liadi, about teshuvah (turning/returning oneself toward God) and preparing for the Days of Awe. We covered a few interesting topics, among them ultimate reality, higher and lower levels of soul, the purpose of Yom Kippur, humans and angels, the views from different states of consciousness, the purpose of creation, transcendent God and immanent God, the true longing of the soul, Jacob-soul and Yisrael-soul, what it means that many religions have similar mystical teachings, the nature of mystical union, and how to prepare for Yom Kippur.

Saturday night we had a short havdalah service (the service separating Shabbat from the rest of the week). I always love havdalah: the singing, the wine, the spices, the flame. Word had come that there had been another bombing in Israel, so we sang a song to awaken compassion in ourselves. We sang it in Hebrew and English; the words in English are, "On behalf of my brothers and friends/ on behalf of my sisters and friends/ let me ask, let me sing, peace to you./ This is the house, the house of God/ I wish the best for you..." I found myself wondering: what does it mean to "wish the best" even for those who hurt us? Is that even possible? I found myself weeping.

After havdalah came more class; by the time we went to bed, my brain was completely full. So much to carry with me into Yom Kippur!

I know now that the melody we sang at that havdalah, the song meant to awaken compassion in ourselves, is L'maan achai v're-ai by Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach:

R' Shlomo Carlebach sings "For The Sake Of My Brothers And Friends."

If you can't see the embedded video, you can go directly to it at YouTube.

This Shabbat Shuvah retreat, back in 2003, was my second time at Elat Chayyim. There was something amazing about discovering that this community of passionate and committed spiritual seekers was still real, that I hadn't dreamed it up the first time I went.

The awful news we mourned that night at havdalah was the Maxim restaurant bombing. I hope and pray for comfort for the families of the victims as Shabbat Shuvah approaches once again. I hope and pray for comfort for all who are impacted by cycles of hatred and violence, there and everywhere.

I wish I knew which texts from R' Schneur Zalman we studied with R' Miles Krassen that weekend. I'd love to return to them now. My jotted scribblings suggest that we talked about what the text called "lower" teshuvah (repenting for our misdeeds) and "higher" teshuvah (a kind of reaching-for-God in response to the knowledge that we are alienated from our Source.)

Shabbat Shuvah means "Shabbat of Return," and the name is meant to evoke teshuvah, repentance / returning-to-God. That first Shabbat Shuvah retreat I attended was when I first learned to sing "return again, return again, return to the land of your soul" -- which felt, at the time, like a chant about returning to Elat Chayyim and to conscious community, but which also carries a much deeper truth.

Shabbat, Shabbat Shuvah, Yom Kippur -- all of these are opportunities to connect with God, to make teshuvah, to re/turn to the place where we live out our highest aspirations and our hearts feel most unfettered and free.

Shabbat shalom, y'all.

A post-Rosh Hashanah poem

AFTER ROSH HASHANAH

I empty the mother jar

measure flour and water

cover the bowl

with a dishtowel tallit

browse the fridge

for one wilted celery

and a faded fennel bulb,

today's wholeness offering

soon uneven dice hiss

their comforting song

as the freezer yields

what it's been withholding

this is how I return

after days of aching ankles

and a heart cracked open

from overuse

stir the unctuous richness

of the holiday now over

match it with pepper

make up the recipe as I go

there's no time

for sourdough's spaciousness;

and how can I cook

when I'm empty as a shofar?

but I feed my own hunger

by turning sad odds and ends

into something fragrant

and sustaining

This is an early draft of a new poem. I suspect that in a week or two or six I'll see ways of improving it. But for now, I wanted to share it.

All feedback welcome, as always.

September 20, 2012

Claudia Serea's Angels & Beasts

Angels & Beasts, the newest release from Phoenicia Publishing, is a strange and wondrous collection. Here's how the publisher describes the collection:

In this largely autobiographical collection of 74

short prose poems, the poet presents her life in three sections. "Angels & Beasts" recalls her early years under the regime of Nicolae Ceasescu, a world of secret terror in which the child interweaves reality and malevolent creatures from Romanian folklore. "The Little Book of Answers" covers the years between the Romanian Revolution (1989) and Serea's emigration to America in 1995. Finally, "The Bank Teller's Name is Jesus" involves the immigrant's impressions of her new home, always colored by the past she carries with her. Serea's masterful use of brevity, surrealism, irony, and black humor allow her to express -- and the reader to confront -- unspeakable horrors. She is a survivor, but a survivor with wide-open eyes, determined to move forward holding the darkness and light together."

That's the book jacket text. But as descriptive as it is, it doesn't do these prose poems justice. Here's one of my early favorites -- one of the lighter ones, I think:

Some angels walk among us looking just like regular people. Sometimes they even play football, like this guy with a sweaty t-shirt. He takes a long drink of water and looks at me knowingly. When he pulls his shirt overhead, I can see the scars where the wings fasten. I'll bet he has them neatly folded in the duffle bag he carries after the game.

I love the image of the sweaty footballer whose scars suggest the temporary amputation of great beating wings.

Here's one of the more disconcerting ones:

White as milk, the stag carries the souls of dead children. He drinks the tears from their mothers' eyes and grazes on thin memory grasses. He stops at the abandoned house to rummage through the rbble, looking for small clothes. The children's souls are nestled in silk swings hooked on the stag's antlers. He carries them gently over treetops and roofs, and into the moon.

I don't know how many of those images are drawn from Romanian folklore and how many are the author's own imagining; regardless, the poem haunts me. (A glance at the notes at the back of the book tells me that the poem is inspired by a Christmas carol about a mythical stag who carries baby Jesus in a silk swing in his antlers.) It's not so much the fact of the souls of dead children, or of an animal who carries them in his horns; it's the "thin memory grasses" and the image of the stag rummaging "through the rubble, looking for small clothes." My heart seizes every time I reread those lines.

One of my favorite poems in the book is this one:

My brother and I emerged victorious after hours of waiting in line, holding a couple of bags with livid animal feet inside. The chicken feet were called flatware, and the pig feet Adidas sneakers. Mom will be so proud of us, we thought. On the way home, we counted: four pieces of flatware, two sneakers, enough to eat for a week.

She says so much in so few words. Hours of waiting in line; livid animal feet; four chicken feet and two pig feet, a week's worth of meat. I can hardly imagine the life which gave rise to these images, to this sharp economy of language. And yet the poem is also -- we have to admit this -- hilariously funny. The chicken feet were called flatware, the pig feet Adidas sneakers! It's the kind of childhood misunderstanding that makes adults giggle despite ourselves. So here I am, laughing helplessly at my imagined vision of two little children who misunderstood the names of the animal feet they were proudly bringing him for a week's worth of dinners.

You turn on the city lights with the strike of a match. The angels march overhead in rows that flicker and flutter, past the sandwich man who holds the sign: BEST WINGS IN TOWN. FREE DELIVERY.

That's from the third section of the book, the section arising out of life in America. Reading it, I think of striking matches to light Shabbat candles, of flipping a switch and seeing a room blaze to well-lit life, of the bright skyline of Manhattan, of the scrolling LED advertisements of Tokyo and Times Square re-visioned into angels, of the horrific massacre of a million tiny angels to make the town's best hot wings.

I'll close with one last poem, also from the book's third section:

Yes

Yes yes yes.

The answer is yes.

Yes: in fall, the leaves get their yellow passports and emigrate from the trees. They all look for a better life in Dirtland, but very few make it there. Most of them are blown down the street by the fall wind. That's how I got here, my dear.

Yes: every church on earth has a mirror church in the sky. This is true for mosques, too. The churches hang upside down and float over mountains and fields, while cardinals toll the bells.

Yes: an orange lily hands from the sky. Its pistil drips the noon light on earth until the hummingbird sticks its tongue inside and drinks.

Here in the hills of western Massachusetts the leaves are beginning to blaze. As they brighten and fall I know these lines will return to me. How many of our ancestors took the leap from the familiar branches of the shtetl, the old country, the old town, looking for a better life? What would they say about the lives their descendants have chosen? I love that reading these poems is reopening these very personal questions for me.

Learn more about the book, read excerpts, read praise for the collection, and order a copy for yourself: Angels & Beasts at Phoenicia Publishing.

September 17, 2012

A teaching from the Sfat Emet for Rosh Hashanah

This is my second-evening-of-Rosh-Hashanah offering, in lieu of a second-night sermon.

A teaching from the Hasidic rabbi known as the Sfat Emet. (Translation mine.)

"Inscribe us for life." [From the High Holiday Amidah: "Remember us for life, O King Who desires life, and inscribe us in the book of life, for Your sake, God of life."]

There is a holy spark in each person's heart. This is the soul, the breath of life. Our Torah blessing says that God "planted eternal life within us." This holy spark within us is what the blessing is referring to.

Over the course of each year, as we grow accustomed to sinning, the material self overpowers that holy point of holiness. Each of us needs to ask for compassion from the Holy Blessed One, so that God will renew the imprint within us at Rosh Hashanah. This is what we're asking when we ask "inscribe us for life."

The two tablets (Exodus) were also inscribed (engraved). Our sages creatively mis-read "engraved" as "set free" -- free from the angel of death and the evil impulse. Upon receiving the Torah, the children of Israel were ready for their engraving -- the words on the tablets and the imprint in their hearts -- never to be erased. But our misdeeds each year mess that up for us. Now each year we need to have that "for life" inscribed within us again.

When we speak of being "sealed" for a good year -- in the Ne'ilah prayers of Yom Kippur -- that's a reference to this holy spark within us, which needs to be "sealed" safely away, like a fountain in the garden of Eden.

Let me unpack and re-state that, because it's beautiful, and it's worth really grasping.

There is a holy spark inside each of us -- something living and eternal, planted there by God.

Each year, our poor choices, our misdeeds, our sins obscure that holy spark.

On this day, we ask God to inscribe us for life -- to uncover and re-awaken the holy spark, the divine imprint, inside us.

Accepting Torah, as our ancestors did at Sinai, frees us from our worst impulses. But when we sin, we lose sight of that.

Today we ask God to inscribe us for life. Not just to inscribe our names in some mythical book, but to inscribe us: to write "to life!" on our hearts.

Our job, says Rabbi Art Green, is to keep the inner tablets of our hearts "free enough from the accumulated grime caused by sin, guilt, the insanely fast pace at which we live, and all the rest," that we maintain the spaciousness to nurture our inner spark.

May we arouse and sustain the inner spark which calls us to holiness, to righteousness, to compassion.

May our prayer on this Rosh Hashanah sluice the grit and grime out of the imprint inscribed on our hearts.

Being Change (A Sermon for Rosh Hashanah)

"Think of Rosh Hashanah as the stem cells of the year." So says my teacher Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, known to his friends and students as Reb Zalman. Stem cells can become anything as they mature and grow; they contain infinite potential. This day on the Jewish calendar is the same way.

The old year has become fixed in time. We know what happened; our memories, both bitter and sweet, are already formed. But we don't know what the new year will contain. The shape of 5773 depends on what we decide to grow out of the stem cells of this day.

The Jewish mystics we know as kabbalists teach that today the door of wisdom and insight opens for us. Tomorrow, on the second day of this holiday, the door of discernment and understanding swings open, too. These are the origin points of our year, our springboard into whatever's coming next.

And who decides what's coming next?

We do.

We can choose to make the coming year a year of lovingkindness. If you went into the new year with the conscious intention of creating compassion, of being kind to yourself and to others, how might that change your 5773?

What if, instead of resenting your body for its limitations or for the five pounds you keep meaning to lose, you made teshuvah and chose to love your body just the way it is? What if, instead of saving your compassion for the people who are already near and dear to you, you set the intention of extending compassion to everyone you meet, every day, everywhere you go? To those who are like you, and those who are not like you; to people of every race, every nationality, every experience?

Caring for ourselves is an act of lovingkindness. So is caring for our families. Changing a diaper, washing a dish, taking out the trash: even these most mundane tasks can be acts of chesed, lovingkindness, if we do them mindfully. What would it take to stimulate your kindness and your compassion today so that they infuse the year to come?

We can choose to make the coming year a year of strength and justice. I could spend all day talking about places where the world needs that from us. Here's one.

The New Israel Fund estimates that 61,000 African foreign nationals currently live in Israel. 70 percent are from Eritrea, 10 percent from Sudan, 10 percent from Darfur, and 10 percent from other African countries. In recent months there has been a wave of xenophobic violence against African immigrants in Israel: riots, beatings, molotov cocktails.

Some Africans came to Israel in search of economic opportunities and a better life. Others fled oppression, genocide, war, and violence.

Our people have been refugees in living memory. We have fled oppression and genocide. My own grandparents, like many of your ancestors, emigrated to someplace new in search of a better life. And yet a member of the Israeli Knesset compared African refugees this summer to cancer infecting the body of the state. How would we feel if a member of a foreign parliament spoke about Jews that way?

Anti-immigrant rhetoric happens here in the US, too. And so does anti-immigrant violence, from KKK factions, white supremacist groups, and even the creators of the free internet game "Border Patrol" in which players gun down Mexican immigrants at the US border.

The commandment most often repeated in Torah is "You shall not oppress the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt." Lord Jonathan Sacks, the Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, offers the following:

The Torah asks why should you not hate the stranger? Because you once stood where he stands now. You know the heart of the stranger because you were once a stranger in the land of Egypt. If you are human, so is he. If he is less than human, so are you. You must fight the hatred in your heart as I once fought the greatest ruler and the strongest empire in the ancient world on your behalf. I made you into the world's archetypal strangers so that you would fight for the rights of strangers – for your own and those of others, wherever they are, whoever they are whatever they are, and whatever the colour of their skin or the nature of their culture, because though they are not in your image, says God, they are nonetheless in Mine.

In the year now beginning, we can choose to say: violence against immigrants, against the powerless, is wrong. Whether here or in Israel. And we will not let it stand.

We can choose to make the coming year a year of harmony and balance.

Lovingkindness is important, but if you take it too far, you can wind up pouring out all of your heart in ways which aren't healthy. Boundaries and judgement are important, but if you take them too far, you can wind up rigid in ways which aren't healthy. But if you keep those two qualities in balance, your compassion and your strength, your love and your sense of justice, that's a beautiful kind of harmony. That's balance.

What would your life look like if everything were in perfect balance? Imagine throwing yourself wholly into your work during the week, and then truly stepping away from it on Shabbat: not just avoiding the office, but giving yourself permission to stop doing and to simply be. Imagine being able to integrate all of the different parts of yourself. Imagine finding your perfect balance of social time and alone-time, sedentary time and active time, time for looking back and time for looking forward. What would that feel like this year?

We can choose to embody endurance this year, and to connect with things which are eternal.

Some of us will face loss in the year to come. Some of us will grieve. Some of us will struggle with infertility, with cancer, with depression. Today we can choose to strengthen the part of us which we know can endure, come what may. We strengthen our power to overcome obstacles -- especially obstacles which stand in the way of ourdesire to bestow goodness on the world. What are the things that matter to you, and can you commit yourself to being persistent in the service of change?

During the years of the Civil Rights struggle, African-Americans and those who stood in solidarity with them sang We shall overcome someday. In Prague in 1989, during the Velvet Revolution, thousands sang this song in Wenceslas square. Its message of hope and liberation speaks now as loudly as it did then: both on a communal level, and on an individual one.

"The arc of the moral universe is long," preached Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, "but it bends toward justice." We can choose to shape this year so that it fits that long curve.

All of this makes it sounds as though we have a lot of power over the coming year! But we can also choose to make this a year of humility.

For all of our plans and hopes and dreams, our charts and to-do lists, we're not in charge. Despite our incredible scientific advances, we don't know everything there is to know. No matter how much we plan for the future, there are things we can't control.

I began to come to terms with that during my year as a student chaplain at Albany Medical Center. That year I walked alongside parents whose child was dying of cancer. An adult whose parent was rushed to the hospital with a heart attack. The sister of the teen who had played "chicken" with an oncoming train. I couldn't take away their pain. All I could do was be with them, and listen, and care.

We want to imagine that if we try hard enough, or perhaps if we are perfectly righteous, we can sidestep suffering. But we can't. The only thing we can control is how we respond to the hand we're dealt. How we treat one another, at the best of times and at the worst of times. Whether we respond to suffering with callousness and disdain, or with kindness and empathy and an open heart.

Can we accept, this year, that we're not in control -- and that that's okay?

We can choose to make the coming year a year of roots and connections. What would the coming year look like if each of us set the intention of being a bridge between people, between different understandings of the world, between one community and another?

Reb Zalman offers the following teaching. Each religion, he says, is an organ in the body of humanity. We need each religion to be unique; Judaism is Judaism, Christianity is Christianity, Islam is Islam, and so on. But we also need each religion to connect with the others. If the heart stopped speaking to the liver, or the lungs stopped speaking to the brain, the body would be in trouble. Just so, he says, we need to connect between our different religious traditions.

When a Sikh temple is attacked in Wisconsin, ripples reverberate through the body of humanity. When a mosque is firebombed in Tennessee, ripples reverberate. When a New Jersey teen attempts to set fire both to a synagogue and to a university building, ripples reverberate.

And: when Jews join with Sikhs in mourning and in prayer, ripples reverberate. When we join with Muslims to stand against Islamophobia in this country, ripples reverberate. When we stand with our own communities against hatred and arson, ripples reverberate. We're all connected. Me to you; us to them. We can live that out in the year to come.

And we can choose, in the coming year, to relate to God in a new way. Someone once asked the Kotzker Rebbe where God is in today's world. His answer: wherever we let God in. In his understanding, God yearns to dwell with us and within us. Are we open to that connection?

Jewish tradition says that today we re-enthrone God as King. Here's another way of understanding that: today we enliven our receptivity to God's presence in creation.

Our sages teach that every year, on Rosh Hashanah, God begins to allocate the energy "budget" to sustain the cosmos for the coming year. Today, life-giving energy flows from the Source of All to revitalize and recharge the depleted "God-field" which by the end of the old year is exhausted and worn. And we can help with that. We can choose to spend the coming year intending to be God's partners in the work of irrigating the world with blessing.

Lovingkindness; justice; balance; endurance; humility; connection; sovereignty. This is not a random list. Kabbalah teaches that these are the seven most accessible sefirot, aspects of divinity. It's hard to connect with the infinity of the Divine, but we can relate to God through these qualities. And these seven qualities are part of who we are, too. Maybe that's what it means to be made in God's image.

Is there significance to the number seven? Seven are the colors of the rainbow. White light appears to be singular, but a prism -- or raindrops! -- can refract that singular light into a seven-color spectrum. That's how I understand the sefirot. God is One, like a beam of white light, and yet we can experience God through these seven qualities, just as the colors of the rainbow are hidden in plain sunlight.

How do you want to reflect and refract light this year? What will come streaming through you into the world: kindness, or indifference? Wholeness, or breakage? Contentment, or frustration? Connection, or alienation? What kind of prism do you want to be this year?

The name Rosh Hashanah is usually translated as "Head of the Year" -- colloquially, the New Year. But the word shanah comes from the same root as shinui, which means change. Rosh Hashanah is the beginning of change.

And that gets back to the stem cell metaphor I offered a few minutes ago. Our liturgy tells us hayom harat olam, "today is the birthday of the world!" Another way to translate that is, "this moment is pregnant with eternity." In this moment, right now, all of eternity -- our whole future -- is waiting to be born. It's up to us what kind of future we "birth" for the year to come. We can shape a year of stasis, or we can shape a year of change.

Change isn't always easy. But one of the ways we understand God is as change itself. When Moshe asks the burning bush "Who are You, anyway?" God responds ehyeh asher ehyeh, "I will be what I will be." God says: I am change and transformation. God says: I am always becoming, and if you follow me, you will be always-becoming, too.

In the new year, what do you want to become? What kind of change do you want to be?

September 16, 2012

Good and sweet

There may be working rabbis who have time to cook when the Days of Awe roll around. I can't really imagine what that would be like. The days leading up to the chagim are always full. There's a near-limitless list of pre-holiday tasks, from making sure all of the honors were assigned, to rolling the Torah scrolls to the right places (ow, my wrists), to generating holiday songsheets and handouts, to making sure my own Torah readings are ready to go, to checking and double-checking that all of the pages of my sermons are printed and are filed in the right places in my machzor...

And I know it could be worse. I'm one of those people who's psychologically incapable of leaving a major writing assignment to the last minute. I know people who operate best in the eleventh hour -- who procastinate until right before a paper is due and then whip out pages upon pages of brilliance. Not I. The process would make me miserable, and the resulting text would reflect the tension and anxiety of its over-fast creation. Instead I wrote my High Holiday sermons slowly, over the summer. So at least I haven't been agonizing over those this week; they are as perfect as they are going to get, and that is all I can do.

It also turns out that life doesn't entirely come to a halt in order to facilitate high holiday planning. (You're stunned, I know.) While doing all of the above, all of us in this line of work are also preparing for Shabbat services, and teaching Hebrew school, and offering pastoral care, and rising to the occasion of whatever illnesses or funerals present themselves in the final days of the year. I don't have statistics on this, per se, but a casual census of my friends tells me that a surprising number of people seem to die during the last days of each year. And we need to care for, and be with, our families; they need us, too.

The point is, I don't cook grand festive meals anymore. This year Ethan is making our erev Rosh Hashanah dinner, which we'll eat early this evening with family before I go to shul for soundcheck. Before Yom Kippur I'll dine at the home of a congregant who has graciously offered a meal at 4:30. (Oy. But that's what one has to do, in order to get to shul before the violinist and cellist begin to play at 5:30, before Kol Nidre at 6.) I'm buying two round challot for Rosh Hashanah -- one with raisins, one without, just like my mother used to have -- from the A-Frame Bakery where Drew and I go every Friday for Shabbat challah. But the one thing I feel the need to make myself, with my own hands, is honeycake.

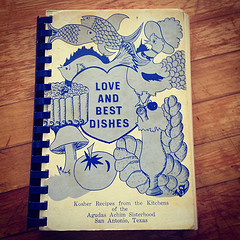

Although I only make it once a year, the recipe is so familiar I barely need to look at the page. This is the only recipe I cook from the Sisterhood cookbook of the synagogue to which we belonged when I was a kid. (Otherwise it's not really my style -- it's more a nostalgia item than a useful cookbook to me, per se.) The book opens naturally to this page, which is stained with coffee and smeary with honey. I no longer need the note I scribbled years ago in the margin, that two loaf pans work as well as a 9 x 9 square. The only thing I adapt is the kind of nut I use; I prefer pecans, because they were the native nut where I grew up, but if we don't have them on hand, I improvise.

The batter goes into the pans. It is smooth and slightly bubbly, thicker than syrup but thinner than dough, a brilliant honey-coffee color. This is a tautology, but it is a color I think of as "the color of honeycake batter." I can't resist licking the spoon as I scrape out the last bits of batter from the bowl after the two pans are full. It's the taste of proto-honeycake; the taste of the season turning; the taste of the new year that's almost, almost, almost upon us. The taste of this liminal moment, one year almost over, a new year almost ready to begin.

Have you ever wondered why the traditional greeting is the wish for a "good and sweet" new year? (Why both?) The traditional interpretation goes like this. Every year is a good year in the eyes of God. God can see the truest and deepest reality of all things. From God's high level of consciousness, it's quite literally all good -- even death, even suffering. But from where we sit, in our limited human consciousness, there's a binary distinction between good and bad, sweet and bitter. When we wish each other a "good and sweet" year, we are saying: I know the coming year will be good in God's eyes, even if some of it doesn't seem good to our way of thinking -- so may the coming year also be sweet in ways which we can discern.

Here's to a good and sweet 5773.

September 12, 2012

A prayer for Tashlich

On the first day of Rosh Hashanah, after morning services, it's customary to go to a body of water and perform the ritual of tashlich, in which we throw breadcrumbs or pieces of bread into the water as a symbolic releasing or casting-away of our mistakes from the previous year.

There are elaborate liturgies for tashlich. In my community this year, we'll use a simple one-page sheet which contains a brief explanation, this prayer, one song, and a shofar call. The pdf is enclosed, below; and here's the prayer. Feel free to use/share if this speaks to you -- I ask only that you keep my name and URL attached, as always.

(This prayer has also been crossposted to Ritualwell: A Prayer for Tashlish at Ritualwell. Thank you, Ritualwell folks, for giving us such a wonderful open-source compendium of ritual materials!)

A Prayer for Tashlich

Here I am again

ready to let go of my mistakes.

Help me to release myself

from all the ways I've missed the mark.

Help me to stop carrying

the karmic baggage of my poor choices.

As I cast this bread upon the waters

lift my troubles off my shoulders.

Help me to know that last year is over,

washed away like crumbs in the current.

Open my heart to blessing and gratitude.

Renew my soul as the dew renews the grasses.

And we say together:

Amen.

One Page Tashlich [pdf] (82kb)

September 11, 2012

Five more mother poems published

Deep thanks to the editors of literary journals Bolts of Silk ("beautiful poems with something to say") and Toasted Cheese for publishing my work this week.

The editor at Bolts of Silk published "Mother Psalm 8;" the editors at Toasted Cheese published "First Night in Buenos Aires," "New World Order," "Sustenance," and "Push."

All five of these poems are part of Waiting to Unfold, my as-yet-unpublished second book manuscript. I'm delighted to see the poems online and am looking forward to browsing more of both journals.

Here are the links: Mother Psalm 8 in Bolts of Silk; Four poems by Rachel Barenblat in Toasted Cheese. Thank you, editors!

September 10, 2012

10 questions

This will be the fourth year that I participate in 10Q, a chance to reflect as the new year begins. 10Q takes place during the Ten Days of Teshuvah between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Every day during that period the organizers email out a question, and participants are invited to post our answers to "the vault," where they are stored until the following year. Here's how they describe it:

Answer one question per day in your own secret online 10Q space. Make your answers serious. Silly. Salacious. However you like. It's your 10Q. When you're finished, hit the magic button and your answers get sent to the secure online 10Q

vault for safekeeping. One year later, the vault will open and your

answers will land back in your email inbox for private reflection. Want

to keep them secret? Perfect. Want to share them, either anonymously or

with attribution, with the wider 10Q community? You can do that too.

Next year the whole process begins again. And the year after that, and the year after that. Do you 10Q? You should.

Click here to get your 10Q on.

As Rosh Hashanah approaches, the 10Q folks have emailed our responses from last year back to us. There's something intense and wonderful and strange about reading what I wrote last year in response to these questions about who I am and who I aspire to be. Here's one of the question-and-answer combinations which resonates most for me now:

How would you like to improve yourself and your life next year? Is there a piece of advice or counsel you received in the past year that could guide you?

I would like to be more grounded, more serene, more kind, more compassionate. I would like to be more attentive to the wonders of my daily life, including my husband and my child. I would like to write more, spend more time with friends, squee more, look at the sky more.

The piece of advice which is coming to mind for me right now is from a Stanley Kunitz poem: "live in the layers, not in the litter." Live in the multilayered, complicated, beautiful world of emotion and time and change. That's what I'd like to do this year.

My response still feels right to me. And I would still list all of these as among my perennial goals. I think I've managed to live up to these hopes, sometimes. (And at other times I've fallen far short, of course. Still human over here.) I used that Kunitz poem in my Yom Kippur sermon last year. It still resonates with me, too.

Now that I'm a working rabbi, answering the ten 10q questions as they arrive each day has become more challenging. (I'm kind of busy during the Days of Awe.) But it's probably good for me; it means I have to answer fairly quickly, offering the answer that's at the top of my head and heart, instead of overthinking.

Anyway. One more reason to look forward to the Days of Awe. Ten good questions, on their way.

Brich Rachamana (now: with sheet music!)

Some years ago I posted about Brich Rachamana -- a one-line grace after meals which derives from Talmud, and for which I have learned two different melodies over my years in Jewish Renewal circles. In that 2008 post I shared simple recordings of both melodies -- Hazzan Jack Kessler's round (I offered one recording of the melody by itself, and another recording which shows how it works as a round) and also the tune borrowed from the Shaker hymn "Sanctuary."

I always wanted to share sheet music, for those who learn better by reading music than by hearing a tune. It's only taken 4+ years, but I finally have the capability of creating very simple sheet music. So, with no further ado, here are the two melodies for Brich Rachamana! (For reasons I don't wholly understand, there's white space at the bottom of each image which I can't seem to crop; apologies for the empty space on the page.) Feel free to use/share/teach these melodies if they speak to you.

First, the melody written by Hazzan Jack Kesseler (text from Talmud and R' Shefa Gold):

Then, the melody from the Shaker hymn "Sanctuary:"

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers