Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 203

January 8, 2013

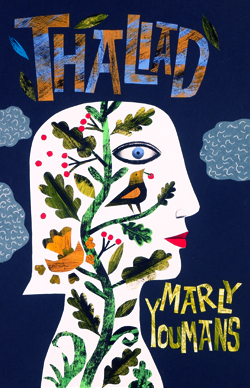

Marly Youmans' Thaliad

I eagerly anticipated my copy of Marly Youmans' Thaliad. Thaliad is the newest title out from Phoenicia Publishing, the same house which brought out my collection 70 faces, and just based on its editor (Beth) and its author (Marly) I knew it would be excellent. As an added bonus, I knew it was illustrated by the Welsh artist Clive Hicks-Jenkins, whose work I also admire.

Here's how the press describes the book:

Thaliad is a book-length epic poem written in accessible, beautiful language that reads like a novel. It tells the story of a group of children, survivors of an apocalypse, who make an arduous journey of escape and then settle in a deserted rural town on the shores of a beautiful lake. There, they must learn how to survive, using tools and knowledge they discover in the ruins of the town, but also how to live together. At the heart of the story is the young girl Thalia, who gradually grows to womanhood, and into the spiritual role for which she was destined.

But for all that I couldn't wait to receive my copy, once it arrived, I found myself reading it slowly, drop by drop, and pausing frequently. Not only because each page is so rich with images, but also because its subject matter turns out to be difficult for me to take in. I keep needing to pause to breathe and to soothe my own heart.

Thaliad begins with an invocation to the muse, as any epic poem ought to do; and then it dives headfirst into the tale of the seven children who survived nuclear apocalypse. They were on a field trip, in a cave, and although rocks fell and they were trapped there, the cave itself protected them. Once they found their way free from their unintentional second womb, they found the world forever changed. This is our narrator, Emma, telling the story of Thalia:

In later years, she never would describe

Her feelings, finding streets emptied of life,

Where shadows of a tree, a woman's hand,

The reaching arm of a young child were burned

Onto sidewalks and walls -- not one of them

Found family at home, unless they were

Corpses, and the rest evaporated

As if they'd flown to some bad fairyland.

I do not know, but Thalia became

The one who urged them through the town to search,

Who had them raid a shop that stank of meat

And threw a picnic underneath a tree,

Who hijacked grocery carts to gather food,

Who kept them close, who made them hide and seek

On commons ground that once had been alive

With daily to and fro but now was gloom --

And then she told them that the act was done,

How they'd no time to wail below the lour

Of skies that wept in ash and turned the day

To twilight, an uneasy, changeless dusk.

If we stay here, we will die, she said,

As everyone we ever loved has died.

Can you see why, as the mother of a three-year-old, I might quail at such description? I'm not generally conscious of the shadow of the fear of nuclear annihilation, but Marly's powerful verse makes this horrific scenario all too real. The world reduced to ash, and children caring for children. Some tender part of me wants to turn away.

This is not a poem which shies away from awful realities. There is violence here, and rot, and fear, and cruelty. Fortunately there is also hope, just enough hope to keep me reading, to keep me trusting that somehow, against all odds, this small band of children will survive to begin the world again.

Here's our narrator, Emma, born years after the apocalypse, pausing to tell a bit of her own story:

Eleven, I was brought before the Clave

That is the forum of full-grown adults

Because each child of age is charged to learn

One mastery from all that's meaningful

And needed by our tribe -- of medicine,

Of roofing and repairing cottages

And buildings, of our waterworks, of wood

That fuels our houses in the wintertime,

Of speaking to the world beyond this world

And catching souls in nets of liturgy...

Emma is anointed, chosen to become the community's bard, "to speak of us in words / translucent to the people," to become "High Storyteller of the fallen world." I love these lines, with their glimpse of how the children in the stolen van must have survived, must have rebuilt. And I love the notion that "catching souls in nets of liturgy" and telling stories clearly are among the masteries which are meaningful and needed by the human tribe, as of course I believe that they are.

Of the seven children who survive the cave-in, one is quickly lost -- kicked out of the vehicle by the others who cannot bear his crying, but when they relent and return for him, he is nowhere to be found. (There's a hint of Lord of the Flies in that moment of unthinking childish exclusion.) Then the first living adult they meet proves to be both violent and on the brink of death. The first trustworthy grown-up they encounter is Doctor Thorn, sixty-three, who finds them once they have chosen to settle beside what I suspect is Otsego Lake, which James Fenimore Cooper called Glimmerglass.

Doctor Thorn is a wonderful grandfather figure for a short while. I love brave young Thalia demanding that the Doctor teach them what he can of medicine, everything they need to know in order to survive. And her impassioned plea:

And maybe we can make a finer world,

One more alive with beauty, where the soul

Can flourish like a tree beside a stream

Despite the poison cast like shadow leaves

From canopies of boughs made pale with ash.

Isn't that what we all yearn for, in the end? To make a finer world, one more alive with beauty, where the soul can flourish?

There's still more tragedy to come. As though the desctruction of civilization as we know it weren't enough, there are also the inevitable sufferings and jealousies of this tiny band of children. There is violence which comes from outside (in a twist I won't spoil for you), and violence which comes from within. But in the end, there's just enough hope for me to cling to.

The epic poem form is not an easy one, and in lesser hands this audacious project would have failed...but Marly makes it work. The subject matter, postapocalyptic survival, is grand enough to merit the form she's chosen -- and the children's journey is told with deep sentiment but no cloying sentimentality. This is a beautiful and powerful book -- worth owning, worth reading and rereading. I am so glad that it exists in the world and that I can turn to it, time and again, glorying in the language and the hope:

The promise harvest years would be ahead,

For conifers and oaks, the hickories

And walnuts, spruces, pines were blossoming

And clouding air with fertile shining silt

That somersaulted in a beam of sun,

That changed the spiderwebs to something rich,

That kissed the surfaces of Glimmerglass

And turned its scalloped border into gold,

That moved across the air as if alive,

The landscape's bright epithalamion,

The simple golden wedding of the world.

Thaliad can be purchased directly from Phoenicia in hardcover or paperback, or from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, and Amazon Europe -- find links to all of those at Phoenicia.

January 6, 2013

D'var Torah for Shemot: Choosing to be Ivrim

This is the d'var Torah I offered yesterday at CBI. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

"The Israelites were fruitful and they swarmed." The root ש/ר/צ / sh-r-tz connotes the unsettling scuttling of insects. Once the Israelites began to multiply in the land of Egypt, something shifted. Torah seems to be hinting that the people -- or at least their Pharaoh -- thought of the Hebrews as nameless, faceless swarming creatures.

"A new Pharaoh arose who did not know Joseph." Our sages debate whether this is literally true. How could the leader of Egypt not know the story of the Israelite who saved the empire from famine? Rashi teaches, it is as though he did not know Joseph. He may have known the Joseph story, but he chose to ignore it. Intriguingly, it's this Pharaoh, the one who perhaps chooses to conveniently forget that an Israelite was once useful to him, who invents the term "Israelite nation." His language subtly portrays the children of Israel as a fifth column living among the Egyptians.

The scholar Judy Klitsner notes that:

Pharaoh's claim that the Israelites are "רַב וְעָצוּם מִמֶּנּוּ / rav ve-atzum mimenu," greater and mightier than we are, is absurd; they are but a small minority in a vast Egyptian empire. But Pharaoh's words are not chosen to report verifiable statistics; they aim for an emotional, fear-inducing impact. Through his exaggerated claim, Pharaoh taps into and amplifies the anxieties of his people who feel as though they are being rapidly outnumbered by the prolific strangers.

Pharaoh whipped the people's anxieties into a froth, and the Egyptians made the Israelites' lives bitter with hard labor.

Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik draws a distinction between two kinds of slavery: being bound to an individual master, and being bound to a totalitarian state. When Joseph worked for Potiphar, he was a slave, but there was a relationship there. Potiphar knew him by name. Some empathy between them was possible. But when the children of Israel were forced to build the cities of Pithom and Rameses, they served an impassive and oppressive regime.

Ordinary people, swayed by Pharaoh's racist rhetoric, came to see the Israelites not as human beings but as swarming things, like cockroaches or rodents. And once it became normal to dehumanize these foreigners, it became possible to enslave them and to afflict them with hard labor, with mortar and with brick.

Portraying outsiders as swarming creatures is a nasty tactic which didn't end with Pharaoh. In Nazi Germany, propaganda films interspersed shots of swarming rodents with shots of the expanding Jewish population. And one needn't look far on the contemporary internet to find horrifying instances of people talking about immigrants who "breed like roaches."

Notably the book of Exodus omits all mention of God from this story of dehumanization. (That's another insight from Judy Klitsner.) When we turn others into nameless, faceless animals, we make God absent. We remove God from the story.

Salvation enters via an unlikely source: l'meyaldot ha-ivriyot / לַמְיַלְּדֹת הָעִבְרִיֹּת, the Israelite midwives Shifrah and Puah. Biblical women often don't get names, but these two do -- which I think

is relevant in this, the book of Shemot, the Biblical book whose name

means "Names." Pharaoh tells them to kill all of the Israelite boys, but they have awe of God, so they disobey.

It's not clear from the text whether these "Israelite midwives" are Hebrew women who act as midwives, or Egyptian women who act as midwives to the Hebrews. The word Ivri, "Hebrew," can also mean boundary-crosser. Perhaps these women are midwives who transgress, who cross boundaries of lawful behavior in order to save the lives of others.

Humanity is still prone -- we ourselves are still prone -- to parroting Pharaoh's ugly way of thinking and speaking about people who are unlike us.

But we are equally capable of playing the roles of Shifrah and Puah -- of cultivating awe of God, and in so doing, opening up new possibilities.

Shifrah and Puah's awe of God gave them strength to disobey Pharaoh and to spare the lives of the baby boys. That act of human decency is what makes possible the birth of Moshe, who will lead the Isralite people from slavery into freedom and into covenant with God.

Each of us has a choice: to be an ordinary Egyptian who succumbs to other people's dehumanizing rhetoric, or to be a brave boundary-crosser who recognizes the essential humanity of every person on this planet.

On this Shabbat Shemot, I bless you: that you should resist the temptation to be part of the nameless masses, or to see anyone else in that way. Instead, may you be blessed to live up to your name, your uniqueness. May you be an Ivri, someone who crosses boundaries in order to work for justice and for human rights. And in so doing, may you make God's presence manifest in our world.

(And we say together: Amen.)

January 4, 2013

Forty Lines About Forty

For the rabbis, forty

signifies fruition:

days before the embryo takes shape,

weeks from conception until birth.

The flood which cleansed the earth

rained for forty days and nights

like a mikvah, which must contain

forty measures of water.

Moses spent forty days atop Sinai

communing with the Holy One

to receive the stone tablets

containing the commandments.

(And forty days praying

after the golden calf disaster,

and forty days atop Sinai again

to bring down the Torah.)

The children of Israel wandered

forty years in the wilderness

before they could learn

what they needed to know.

The sages in Pirkei Avot

(Ethics of the Fathers)

teach that a man of forty

attains understanding.

The Talmud teaches

"one does not fully comprehend

the knowledge of one's teacher

before forty years"

and also "one does not become

fit to teach

(the things that matter)

until forty years."

When Rabbi Zeira wanted to learn

the Jerusalem Talmud, he fasted

forty times to forget what he'd learned

of the Babylonian Talmud

(like Nan-in who had to empty his cup

before the Zen master could fill him.)

Forty means new beginnings,

blessings waiting to unfold.

January 3, 2013

Re-sharing a forgotten Torah poem

Looking back at my previous offerings for this week's Torah portion -- Shemot, the first parsha in the book of Shemot, which is known in English as Exodus -- I rediscovered a Torah poem I'd forgotten I'd written: Labor. I wrote it and shared it here during January of 2010, a scant handful of weeks after our son was born. (No wonder I don't remember writing it! Those first couple of months are a blur to me now.) Rereading it now transports me back to the birthing room. I suspect that my sense of Shifrah and Puah, the two midwives listed in this week's portion, has been permanently changed by the experience of giving birth.

This is one of the things I love about reading Torah year after year. The text is unchanging: the same handwritten words on the same aging vellum. (Or typeset and printed on paper, or blazing forth from a computer or ipad screen.) But we bring ourselves to bear on the text: our experiences, our dreams, our hopes, our fears. Being a parent changes the way I read Torah. I empathize with the parents in our holy text; I empathize with God as the cosmic Parent (Who is, I would argue, learning to parent creation as S/he goes along, just as any human parent learns how to rear a child by diving in and doing it.)

And someday, I imagine, becoming a grandparent will change the way I read Torah. I can't imagine, now, what will resonate for me in this text when I enter my sage-ing years. But I know that I'll still be searching for meaning in this text then. That's another one of the things I love about reading Torah year after year. We've made a commitment to each other, Torah and I. Torah promises to be here always, to be rife with possibilities, to spark my imagination and my spirit; I promise to keep reading, to keep turning and turning to see what I find in her this time around.

Hold the parsha up to the light and see what shines forth for you this year.

(As always, you can find my previous divrei Torah and Torah poems at the Velveteen Rabbi's Torah Commentary index page, listed by parsha and by year. The 2013 d'var Torah for this week's parsha will go live on Sunday, once we've moved into the new week -- I'll be sharing it at my shul on Shabbat morning, so if you're burning to find out what I have to say about Shemot this year, come daven with us at CBI!)

December 27, 2012

My top ten VR posts of 2012

The Gregorian year is winding down: time to go back through all of my 2012 posts, and choose the ones I think are best, or most enduring, or most worth highlighting one more time. I've come up with ten favorite prose posts from the last twelve months. And here they are, organized chronologically:

Living in Jewish time. "I used to wonder what it was like to be a dancer. To have a whole choreographed performance internalized in your body, such that even as you're dancing one movement, you know what movements come next, and after that, and after that. I still can't imagine the literal experience, but on some level, I think maybe it's a little bit like this experience of being rooted in the Jewish year. Doing the dance steps of Tu BiShvat, knowing that the Purim steps come next, and the Pesach steps, the Omer steps, the Shavuot steps. It's a balancing act, being wholly in this moment even as I try to lay the groundwork for moments to come."

Bedside. "It is humbling to sit by the bedside of someone who is transitioning out of this life."

The black dog, the shadow, the fog. "No one "deserves" depression. The voice of depression often whispers, insidiously, that this is who one really is, this is what life really is, that anything which has seemed pleasurable or joyful was merely an illusion -- but it's not true. Depression does not mean that you are weak-willed or not trying hard enough. Depression is real and it is awful -- and there are ways to banish it. If one way doesn't work, there are others. Always."

Sleeping and waking, Torah and revelation. "In the Hasidic understanding, the Torah which we know in this world is a physical manifestation of -- and also a pale reflection of -- the supernal Torah which is known to God on high. Bereshit Rabbah (a classical commentary on Genesis) teaches us that when a person sleeps, a portion of their soul ascends on high and is united with God; upon waking, the soul returns to the body. Who can know what Torah was revealed to our ancestors in that holy sleep? Their souls (or, as another midrash has it, our souls -- since we all stood at Sinai, every Jewish soul which has ever been or will ever be) ascended on high and connected with God. And then they woke up, and received revelation in a different way."

The moment, here and gone. "Now that the big-boy bed sits in boxes in our entry foyer waiting to be assembled, I'm discovering that I wasn't exactly correct when I swore I would never miss those early days. There are things I miss, though most of them are hard to verbalize -- like his peachfuzzed baby head with its scent of milk. When Drew needs comfort now, it's a bit of a struggle to fold his long-limbed body into mine, his head onto my shoulder. When I put him to bed now, hefting him up into my arms and over the bar into the crib, I know our days of this particular bedtime routine are numbered. There's a poignancy in that."

Cultivating equanimity. " Maybe equanimity is the quality which enables us to encompass both the moments of blissful connection and the moments of agonizing disconnect. Because I can't stay in that lofty headspace and heartspace, no matter how I wish I could. At some point, we always have to leave mochin d'gadlut (expanded consciousness or "big mind") for mochin d'katnut (constricted consciousness or "small mind.") For me, the question is: once I'm back in "small mind," how will I respond to the world around me? How will I respond to injustice, to unkindness, to lack? How will I respond to compassion, to connection, to joy?"

Wishing for a different communal discourse. "Why does it matter to me that someone is "wrong on the internet"? Because this is part of a bigger picture of people trying to define who's "in" and who's "out;" because this is part of an attempt to define me, and my colleagues, with words we would not use to describe ourselves; because labeling us as "anti-Israel activists" is not only factually wrong, but also hurtful; because this is part of an attempt to bully and silence those of us in the Jewish community who criticize Israel's policies, and I don't think it's wise or healthy to create a situation in which anyone who critiques Israel is considered beyond the pale."

Ten years in Jewish Renewal. "I came home from that first week at Elat Chayyim and said to Ethan, "I've found my teachers. Someday I want to be a rabbi like they are rabbis." // Ten years. Could I have imagined, then, who and where I would be now?"

A sermon for Yom Kippur Morning: In The Belly of the Whale. "Once his ship is at sea, a mighty storm arises. The sailors are in a panic. And Jonah is sound asleep belowdecks. This is comedy. Imagine the ship rocking wildly from side to side, sloshing with seawater and in danger of foundering: and our hero, or perhaps our anti-hero, is sound asleep! // It's also a deep spiritual teaching. How often, in our lives, do we hide from what we know we're meant to be doing? How often are we spiritually asleep?"

On 'Otherness' at Christmas. "I think there's something profoundly valuable in the de-centering experience of recognizing that one's own paradigm is not the only paradigm. But I recognize that it isn't always easy or comfortable. And if it isn't happening in a reciprocal way -- where I recognize that my way isn't the only way, but so does the other guy; specifically, so does the person with the privilege of being in the dominant / majority position -- it can feel alienating and painful. Everyone else is having a great time and I'm outside the party -- alienating and painful. That mainstream experience is "normal," and I feel perennially "other" -- alienating and painful. // Nu, what to do?"

Here's to 2013!

Jewish Renewal voices on the UN vote recognizing Palestine

Last week, OHALAH -- the association of Jewish Renewal clergy -- voted on a resolution regarding UN recognition of Palestine. The resolution is now posted on the OHALAH website: Majority Opinion Among OHALAH Members on the UN Vote Recognizing Palestine and its Aftermath.

I'm proud of our community on several levels. First: I know that this resolution was a challenge to draft. This resolution was drafted by several members of the organization's tikkun olam committee, where there is a wide diversity of political and spiritual stances when it comes to Israel. So reaching a resolution on which all of us on the committee could agree was a victory. Second: once we brought the resolution to the broader OHALAH community, there was a lot of discussion on our list-serv. The conversation there was impassioned but productive. From where I sit, that's a victory too.

And finally: we're putting forth a majority opinion which says some things which I haven't heard any of the other major Jewish organizational voices saying. Such as:

[W]e are aware that the recent recognition of Palestine by the UN General Assembly is a tremendously important and profound moment for the Palestinian people. We honor its importance to the Palestinian people, even though many of us greet the news with trepidation about what this will mean for Israel. Only time will tell whether or not this recognition will actually move the peace process forward. We pray that this is a moment when hearts can open, and steps can be taken to pursue peace, and we call on both Israel and the newly-recognized Palestine to do everything in their power to actively pursue a just, lasting and secure peace.

This is a beautiful articulation of how I felt about the recognition of Palestine by the UN General Assembly. I don't know what it means for the future, but I recognize and honor that it's a big deal for the Palestinian community. I hope that this gesture on the part of the UN will help to create a situation where both peoples can negotiate a just and lasting peace from a new vantage. And yes, I pray that this is a moment when hearts can open and steps can be taken to pursue peace. Absolutely. Amen!

I also like the fact that this statement grounds these hopes in text:

As our sages taught centuries ago, when they interpreted Psalms 34:14, "Seek peace, and pursue it": "So great is peace, that you must seek peace for your own place, and pursue it even in another place" (Leviticus Rabah 9:9). As we seek peace for our own place, for the home of the Jewish people, we also accept our obligation to pursue peace in another's place, for another people as well as for ourselves.

Therefore, we call upon Israel and the Palestinian Authority to enter into direct bilateral negotiations. We agree with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton who said that "the only way to get a lasting solution is to commence direct negotiations." Therefore, we support the United States using its influence to bring the parties together for such negotiations.

We urge the three major parties involved in this process to avoid actions which may be seen as being retaliatory, reactionary, punishing or threatening to the commencement of direct negotiations.

What moves me here is the interpretation of the Leviticus Rabbah quote: that "seek peace and pursue it" means not only to seek peace for one's own place, but also to pursue it even in another place. We can read that as: seek peace from one's own place, and pursue it from the Other's place. Our tradition calls us to place ourselves in the position of the Other -- for me as a Jew, that means to try to stand in a Palestinian's shoes -- and seek peace not only from my own standpoint, but also from theirs. This is powerful stuff. (And I give kavod to R' David Seidenberg, who brought this particular interpretation to the table.)

I'm gladdened to be part of a clergy association which can accept this statement as a majority opinion among our members. May our hopes for peace be realized, speedily and soon.

December 24, 2012

The year winds down

There's no preschool today or tomorrow, so instead of spending these days at shul / at my desk, I'm spending them with our son. Today we'll alternate between watching Peanuts cartoons and playing with trains and paints at home, and running a few errands to prepare for our evening.

We're continuing last year's tradition of hosting some friends and family for dinner tonight (which I can't resist calling erev Christmas), and -- like last year -- Ethan's going to make zely and knedliky again -- Czech red cabbage and bread dumplings -- as a nod to my grandmother Lali, of blessed memory.

My online time is likely to be limited between now and early January, so I'll take this opportunity to wish all of y'all a lovely end-of-the-Gregorian-year! To those who celebrate Christmas tonight and tomorrow, may your holiday be filled with meaning, merry and bright.

December 21, 2012

Three poems from the book of Judges

The book of Judges contains some powerful stories. Some years ago I wrote a trio of poems exploring three of those stories and the women who feature in them: the judge and prophet Devorah, Yael who slew the general Sisera, and the nameless daughter of Yiftach (in English, his name is usually rendered Jephthah.)

Tekufat tevet, the winter solstice, is regarded as the date when Yiftach's daughter was killed. These are dark stories, but powerful ones. Today's the solstice, so I thought I'd share my trio of poems arising out of the book of Judges. If this interests you, don't miss Alicia Ostriker's long poem / ritual script Jephthah's Daughter: A Lament, available at Tel Shemesh.

JUDGES TRYPTICH

1. Devorah

Beneath her palm tree, Devorah

(the honey bee, her sting intact)

judged the acts of the Israelites

the people came with gifts

of oil and flour and yearling lambs

and she answered them with justice

she sent for Barak in his leathers

words fell from her mouth like honey

and he yearned to taste her sweetness

come with me, he pleaded

I will relinquish my own glory

if I can have you by my side

nine hundred iron chariots thundered

the Infinite cast panic like a spell

and all Sisera's army was slain

and Devorah slept, and dreamed

Sisera stumbles into a woman's tent

Jael's doors open wide to let him in

he drinks milk fermented in goatskin

he slides into sleep: her tent pin rests

at his sweaty temple: she drives it home

2. Jael

My husband is a Kenite

Kenites don't take sides

so when God told me what to do

I kept it to myself

someday the sages

will credit me with pluck

and righteousness, even if

my methods were obscure

but Sisera's mother

wrapped in happy fantasies

of her precious son's return

will never be the same

the rabbis say

Sisera demanded my body

the rabbis say

we slept together seven times

but you don't get to know

you can claim me

as a righteous convert

but my story is my own

3. Yiftach's Daughter

Israel whored with foreign gods

until Yiftach, prostitute's son, rose up

wearing holy spirit like a cloak, saying

deliver the Ammonites into my hands

and whatever exits my house to meet me

will be sacrificed to You in holy fire

and out came his only daughter

bare feet flying to greet him, Daddy!

with her tambourine beneath her arm

he rent his garments in grief

she bent her head in submission

to her father and his God's demands

two months with her friends in the hills

(curve of soft hips beneath her hands,

stretch of skin salted with hot tears)

and she returned home, pale

but resolute, and bared her neck

her father steeled himself to raise his knife

the sun went down early, turning away

from the war hero with bloodied hands

the mothers wept like the opened skies

when he burned her bones

no prophet spoke God's anger

and the maidens mourned alone

December 20, 2012

Rejecting erosion

A Rabbi Without Borders: Doesn't worry, at least not very much, about dilution, or work from a narrative of erosion.

That's item six on the Rabbis Without Borders FAQ. Of all the things we talked about during the two days of our first fellows gathering, this is the one I find myself continuing to mull over and contemplate as the week continues to unfold.

Messages about the dilution and erosion of Judaism are surprisingly pervasive. I think of the anti-intermarriage rhetoric which is rooted in the fear that the Jewish community is disappearing (see A New Demographic, JewishPost.com), and the ways in which Birthright trips seem designed to encourage inmarriage (see Breeding Zionism, Tablet, 2010.) I think of the generalized sense that there were "good old days" and that our generation is sadly far from them: our Jewish educations aren't what they once were, our Jewish commitment isn't what it once was, that sort of thing.

Sometimes I'm susceptible to this narrative too. Not on the intermarriage anxiety front, but the Jewish education one. I imagine an earlier moment in time when -- at least in my fantasy -- every Jew was well-grounded in Jewish texts and practices, when basic liturgical and Torah literacy were a given. It's an easy thing to feel nostalgic about, in a moment when a lot of people don't necessarily have that grounding (and don't necessarily wish for it, either.)

But while it may be true that once upon a time we all knew our own tradition's canon, two other things were also true at that moment: the canon was a lot smaller, and the "we" was smaller too. (That insight comes from R' Brad Hirschfield.) I like being part of a diverse "we" -- diverse across all kinds of spectra: gender and sexuality, ethnicity, knowledge, practice. And I don't actually want to return to that more insular moment or to that time when our own canon was the only learning available to us.

I don't see today's intermarriage rates (or the rise in "nones" -- see Pew Forum: 'No Religion' on the rise, 2012) as dangers to Judaism or to Jewish community. Yes, our communities are more permeable than they used to be, and an increasing number of people are choosing and changing and crossing boundaries -- or, in R' Irwin Kula's terms, "mixing, blending, bending, and switching." (See his essay From the Cathedral to the Bazaar, HuffPo, 2010.) But I'd rather see those realities as opportunities to collaborate in writing a new chapter of our story than as occasion for sounding the alarm.

And I love the breadth and range of knowledge and passion which are open to, and cherished by, the communities I serve -- even if that knowledge isn't necessarily Jewish.

I want to celebrate living in a moment when both our sense of our canon, and our sense of our "we," is expansive. A moment we can cultivate a cosmopolitan sense of ourselves as connected with other communities and cultures, not merely concerned with our own story or our own texts or our own ways of thinking. This potential for intellectual and spiritual expansiveness is one of our era's greatest gifts.

My teacher Reb Zalman speaks sometimes in terms of needing both the rearview mirror (so we can see where we've been) and the front windshield (so we can see where we're going.) I don't want to lose the rear view, but I'm also excited to be heading into new territory. And I don't believe that this new territory is one of disaster. The long and the short of it is, I don't want to buy into the negativity

encoded in the narratives of dilution and erosion. They're not "the"

story -- simply "a" story. I'd rather tell a different one.

Here's a different story: there are things I love, and I want to share them with you. I've inherited a deep toolbox of texts and practices passed down through generations, a box chock-full of wisdom and ideas and insights: old ones and new ones, useful ones and odd ones. I'd like to teach the use of these weird and wonderful tools. Not because they're endangered or because you "have to" learn them or rescuscitate them or save them, but because they're valuable ways of interacting with the history and the present, with the world around us, with emotional and spiritual life, with something beyond ourselves.

I love Jewish texts and teachings, Jewish modes of prayer, Jewish ways of experiencing the world and encountering God. I love them so much that I want to share them with everyone I meet. And one of the wonders of living in this moment of time is that I can do that, here on this blog. What an incredible gift it is to be able to share some of the riches of my tradition with people who are thirsty for -- or at least curious about! -- those riches. I don't know how to measure the impact of this work, and I don't ever expect to be finished with it, but I love that I get to do it in the first place.

And I love living at a time when there's so much capacity for bridge-building and interconnection. Between different cultures, between different communities, between different experiences, between different understandings of God. This is an amazing moment to be Jewish; it's an amazing moment to be a spiritual seeker; it's an amazing moment to be in the world. So the ground is shifting beneath our feet. Dare I hope that maybe we're on the verge of figuring out how to fly?

December 17, 2012

Rabbis Without Borders, kirtan, wow

I've done kirtan before. I've even done kirtan with the Kirtan Rabbi, Rabbi Andrew Hahn, before. So when I saw it on our agenda, this morning, I smiled, and I thought, wow, that's going to blow a few minds. I didn't realize one of them would be mine.

Today was the first day of the first meeting of the fourth cohort of the Rabbis Without Borders fellowship. This morning we introduced ourselves by way of pennies, broke into small groups to talk about objects which matter to us (Jewish objects, "non-Jewish objects," and objects which others might think are non-Jewish but which feel Jewish to us -- after meeting with my small group I tweeted that I'm not sure there are non-Jewish objects anymore), and listened to Lisa Miller, religion editor at Newsweek, talk about religious demographics in the United States today.

Rabbi Brad Hirschfield led a fantastic afternoon session exploring and recontextualizing the statistics Lisa had placed before us. I want to blog about that, at some point. I have a lot of thoughts and ideas bouncing around my head now. I'm thinking a lot about the notion that the rising number of "nones" -- those who aren't affiliated with any religious tradition; who check the "none" box on surveys -- is not an ending but a beginning. An opening for a new chapter which we may, if we are awake and aware, be blessed to help co-author.

But the thing I want to write about tonight was our evening program, which was Hebrew kirtan with the Kirtan Rabbi. Kirtan is devotional chanting. In its original context, it's a kind of bhakti yoga -- a devotional practice of chanting divine names in order to open up the heart. Reb Drew led us in an evening of chanting, interspersed with narrative. He told us, over the course of the evening, how he came to explore this form of sacred practice and to integrate it with Judaism.

One of the chants which moved me was a variation on the shema. It features a variety of names for God: not only Adonai and Yah but also hesed, gevurah, tiferet -- the classical kabbalistic sefirot. I smiled as those names unfolded. I thought, ah, I see what he's doing there, that's very lovely. I enjoyed the chanting, and then when the chant was done I enjoyed the experience of singing the full shema once as our chatimah.

But the chant which really got me was his chant which works with the kaddish. There are several parts to the melody, and we chanted each one in turn. L'eilah min kol birchata u-shirata -- beyond all blessings and songs. Y'hei shmei rabbah m'vorach -- may the Great Name be blessed. One of the melodic lines is borrowed from the way the kaddish is sung on Friday nights, so I grinned the first time we sang it -- a familiar melody and familiar words, shifted and changed by their new context. I was surprised by how much joy and energy we brought to singing that line.

This is hard to describe; I'm not doing it justice. We reached a place where we were singing his kaddish kirtan in harmony -- the women singing one melodic line and set of words, the men singing another -- and all of a sudden my heart cracked open and I burst into tears. Quietly, mind you; I don't think most of the room noticed. I covered my face with my hands and took a few deep breaths and then I was able to sing again, though softly. By the time we finished the kaddish my face was wet and all I could think was that this must be what it's like to be part of the choirs of angels singing holy holy holy back and forth all day.

I've been blessed to have this kind of peak experience many times over my years in Jewish Renewal, but I wasn't expecting to have it tonight. (I've heard Reb Zalman speak several times about the challenge of "domesticating" the peak experience -- taking the peak experiences we may be blessed to have on retreat, and bringing them home with us, bringing that energy home to enliven our daily prayer lives.) I didn't see it coming, and there it was: a surprise from God, a moment of intense connection where my heart opened wide and God poured in.

Maybe it was because I was chanting kirtan in such an intimate setting -- this RWB cohort is a scant 18 people, so it was an intimate room, all of us seated close together and close to the music. Maybe because everyone in the room knew what the words meant (while I think most kirtan afficionadoes would say that the experience of chanting is meaningful even if the words are opaque -- come to think of it, that's one of the arguments I've used for davening in Hebrew even when one isn't fluent, too -- I do think that something is added when one knows what one is praying.)

One way or another, it was wonderful experience. I'm grateful to Reb Drew and his wonderful ensemble (especially Shoshanna Jedwab, whose drumming -- when I encounter it -- always enlivens my prayer). To my RWB cohort for willingness to enter into this admittedly non-traditional experience (which we'll be processing and discussing tomorrow morning -- that should be fascinating in its own right!) To RWB/Clal for creating the container within which this could all take place.

Several of my colleagues and I took the subway back to our hotel together, still talking about the evening. As I write this post now I feel as though I'm still vibrating faintly from this intense and wonderful day of conversations and connections and song.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers