Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 201

January 25, 2013

The sap begins to rise

The holiday cycle is a circle; every year it repeats. There are exceptions -- marvels like birkat ha-chamah, which happens only every 28 years -- but on the whole, we celebrate the same holidays year in and year out. Tonight at sundown we'll enter not only into Shabbat but also into Tu BiShvat, the New Year of the Trees. One month later, the next full moon will coincide with Purim. One month later, the next full moon will bring us Pesach. Seven weeks and one day after that, Shavuot.

The holiday cycle is a circle; every year it repeats. There are exceptions -- marvels like birkat ha-chamah, which happens only every 28 years -- but on the whole, we celebrate the same holidays year in and year out. Tonight at sundown we'll enter not only into Shabbat but also into Tu BiShvat, the New Year of the Trees. One month later, the next full moon will coincide with Purim. One month later, the next full moon will bring us Pesach. Seven weeks and one day after that, Shavuot.

There's meaning in the way one holiday leads to the next. Just as Shabbat is more special when seen against the backdrop of the weekdays which surround it, each festival is subtly shaped by its place in the wheel of the year. Tu BiShvat, which begins tonight, is the first step on a journey which will lead us to the revelation of Torah and the flowering of glories we can only now imagine. For those of us in the Northern hemisphere, it's our first step toward the abundance of summer.

Rashi teaches that Tu BiShvat is when the sap begins to rise to feed the leaves and fruit of trees for the year to come. Where I live, we're experiencing the bitter cold of deep winter. At sunrise a few days ago the thermometer registered one solitary degree above zero (Fahrenheit.) We bundle up, we hunker down, we go inward. The freedom of spring feels far away. It's hard to imagine the air becoming soft, forgiving, fragrant with new life instead of with woodsmoke and snow. TuBiShvat invites us to recognize that the sap begins to rise precisely at the moment when winter feels most entrenched.

Rashi teaches that Tu BiShvat is when the sap begins to rise to feed the leaves and fruit of trees for the year to come. Where I live, we're experiencing the bitter cold of deep winter. At sunrise a few days ago the thermometer registered one solitary degree above zero (Fahrenheit.) We bundle up, we hunker down, we go inward. The freedom of spring feels far away. It's hard to imagine the air becoming soft, forgiving, fragrant with new life instead of with woodsmoke and snow. TuBiShvat invites us to recognize that the sap begins to rise precisely at the moment when winter feels most entrenched.

And the sap is rising not only on a literal level (though I expect to see maple trees tapped for syrup in a few weeks, when we have above-freezing days and below-freezing nights) but also on a spiritual level. This is the season when we open ourselves to trusting that new ideas, prayers, insights, spiritual "juices" will rise in us. Even if spiritual growth is invisible, we trust that it's taking place.

I've always loved the Norse stories about Yggdrasil, the cosmic tree which contains nine worlds between its roots and its branches. Judaism too has teachings about a cosmic tree, the Tree of the Sefirot -- ten qualities or aspects of God, envisioned through the metaphor of a tree with creation at its roots and infinite unknowable God beyond its highest branches. Tu BiShvat is an opportunity to journey through that cosmic tree, a chance to prayerfully and meditatively ascend from roots toward branches toward what's beyond our ken.

I've always loved the Norse stories about Yggdrasil, the cosmic tree which contains nine worlds between its roots and its branches. Judaism too has teachings about a cosmic tree, the Tree of the Sefirot -- ten qualities or aspects of God, envisioned through the metaphor of a tree with creation at its roots and infinite unknowable God beyond its highest branches. Tu BiShvat is an opportunity to journey through that cosmic tree, a chance to prayerfully and meditatively ascend from roots toward branches toward what's beyond our ken.

And, of course, Tu BiShvat is a chance to just celebrate trees. To sing happy birthday to the trees (as I did with my son and our other Hand in Hand students last week), to wander in the woods and greet the trees and connect with their quiet sturdy presence. One of the ways we celebrate trees is through eating their nuts and fruits with mindfulness (accompanied by the blessing for tree fruits which sanctifies that act of consumption). The kabbalists saw this as a tikkun, a healing. I suspect most of us need to strive for healing in our relationships with food and eating, and with the natural world on which we depend.

Imagine eating a piece of tree fruit with complete focus, with the intention of being conscious of the incredible flow of energy which went into that fruit's growth and the miraculous flow of divine blessing which resulted in the fruit being here for you to eat. That apple isn't just an apple; it's a gift from God! And when we enjoy the apple with gratitude and mindfulness, and we thank the Source of Blessing, we're stimulating the flow of more blessing into the world, causing more abundance to flow so that we can be fed in the new growing season to come. That's what our tradition teaches.

Imagine eating a piece of tree fruit with complete focus, with the intention of being conscious of the incredible flow of energy which went into that fruit's growth and the miraculous flow of divine blessing which resulted in the fruit being here for you to eat. That apple isn't just an apple; it's a gift from God! And when we enjoy the apple with gratitude and mindfulness, and we thank the Source of Blessing, we're stimulating the flow of more blessing into the world, causing more abundance to flow so that we can be fed in the new growing season to come. That's what our tradition teaches.

A person should intend [on Tu BiShvat], when reciting a blessing, to channel divine life-energy to all creations and creatures -- inanimate, plant, animal and human. One should believe with perfect faith that the blessed God gives life to them all and that there is a spark of divine life-energy in every thing, which gives it existence, enlivens it, and causes it to grow. —Rabbi Avraham Yaakov of Sadiger (19th c.)

If you need a haggadah for a Tu BiShvat seder, here are three Tu BiShvat haggadot (one for really little kids, one for kids aged 7 through 11, and one for adults and older kids -- we'll be using the third one at my shul's Tu BiShvat seder / Shabbat potluck tonight.) But regardless of whether or not you're formally celebrating Tu BiShvat, I hope you'll take some time tonight and tomorrow to consider trees, and to be grateful for them -- and to rejoice as your own spiritual sap begins to rise.

January 24, 2013

Imperfect poetry: nursing, remembered

NURSING, REMEMBERED

the first weeks were endless:

my nipples sore, your mouth

lined with ground glass

bowls of salt water

balanced on the tabletop

an astringent immersion

my breasts as raw

as my bruised heart,

overflowing without warning

would we survive three months

the hard candy I worried

beneath my tongue

sometimes I try to remember

the heavy prickle of milk

on the verge of letting down

but those doors are closed

and the key is lost

or packed away

with the newborn clothes

I no longer believe

you could ever have worn

as inaccessible

as the woman I used to be

before you made me new

This week's imperfect prose prompt at Emily Wierenga's blog is Mother. (And here's her post on the theme -- with links at the end to posts by others who've written to the prompt.)

The prompt sent me back to reread the first mother poem I wrote, during the first week of my new life as a mother: El Shaddai (Nursing Poem). And then rereading that sparked a new poem. (I know it's an imperfect prose prompt, not a poetry prompt, but it inspired a poem -- what can I say.)

It's easy to get so caught-up in this moment of mothering -- the joys and vagaries of parenting a three-year-old -- that I forget what it was like, what I was like, when this whole wild journey began. How overwhelming it was to go from childless adult life to parenting a newborn. The things which hurt in all four worlds -- physically, emotionally, intellectually, spiritually.

I don't want to forget how hard it was, or how miraculous. (And it was both of those things. Deeply.) I love this life with a rambunctious boy who climbs and jumps and laughs and plays with trucks and marbles and sings the alphabet to me at night in lieu of the lullaby I used to sing to him. But we couldn't have gotten here without going through there.

And I suspect that my sense of God is forever changed by the experiences of pregnancy and parenthood -- especially early parenthood. All of our parental metaphors speak to me in a different way now than they did before. I can't help wondering: if becoming a parent deepened and opened me, in the deep ways which I know it did, can we imagine that the same is true for God?

(And -- I can't resist putting in a plug for this, even though it's not out yet! -- if you like this poem, stay tuned for the forthcoming publication of Waiting to Unfold, my collection of first-year mother poems, which is coming out from Phoenicia later this year.)

January 23, 2013

Twenty years of song

In January of 1993, a woman named Kate put out the word that she was looking for people who were interested in singing madrigals during Winter Study, Williams College's January term. My dear friend David told me in no uncertain terms that he was going, and he was dragging me with him. I was mourning the break-up of my first real relationship, and I was morose; he knew that singing would cheer me. I was as dubious about that proposition as only a self-centered and heartbroken seventeen-year-old could be, but I agreed to give it a try.

To my surprise, David turned out to be right. The singing was grand, and it lifted me out of myself. We had so much fun during Winter Study that, when the spring semester began, we decided to constitute ourselves as a "real" a cappella group, specializing in madrigals and early Renaissance music. David and Kate became the group's first pair of directors, and they opened auditions to the campus-at-large. To my great relief, I made it into the group. Once the group's line-up was settled, we spent an afternoon brainstorming names. And the name we chose for ourselves was the Elizabethans.

The women, and the men, of the Elizabethans. Spring 1994.

I sang with the 'bethans all four years of college, and the year afterwards, too, when I was working at the college bookstore. Infinite hours of rehearsals -- concerts on campus, music interspersed with skits and patter and silliness -- annual tours when we packed ourselves into a college van or two and drove all over the Northeast (and sometimes as far south as North Carolina) to perform at colleges and churches, doing guest stints with other madrigal groups, singing wherever we could line up a gig, and then cooking meals for ourselves at night in borrowed kitchens -- these make up some of my fondest college memories.

It turns out that the era of making

memories with the Elizabethans isn't over. Not entirely, anyway.

Concert flyer, 20th Reunion Concert, this past weekend.

We developed a tradition years ago of gathering to sing together -- current students and alumni alike -- one weekend in January, during Winter Study, to commemorate the founding of the group. We'd gather, sing for an afternoon, eat a few meals, and enjoy reminiscing and meeting the new folks. To honor the 10th anniversary of our founding, we put on a concert, joking among ourselves that we were the Pan-Bethan Tabernacle Choir. The concert was a blast, so we did it again for the 15th anniversary. (See Fifteen years of song.)

And this past weekend, we did it again, putting on a concert in celebration of the group's 20th anniversary.

20 years' worth of Elizabethans. (I'm in the second row, all the way at the right, partially obscured.)

The Elizabethans reunion took place over MLK weekend, a scant 36 hours after I got home from OHALAH. We spent most of Saturday afternoon rehearsing, and put on a concert on Saturday night. I realized, a short while into our rehearsal, that I still knew most of our old repertoire by heart. I realized, too, that I've spent more of my life with this music than without it -- I started singing madrigals at 17, and I've been singing them for 20 years. Beyond that: I've been singing some of these songs for longer than some of the current students in the group have been alive. (That blows my mind.)

Singing with the Elizabethans again was a real joy. I love this music. I love singing a cappella, especially madrigals and renaissance music, especially with other people who love the singing as much as I do. There's something deeply meaningful for me about the experience of joining my voice in song with other people, shaping my voice to fit with theirs, collaborating to create something beautiful and ineffable, more than the sum of its parts. And I love having the chance to sing again with people I've been singing with for twenty years. That's a tremendous gift.

I'm grateful for the opportunity to sing beautiful music with old friends and new friends alike, and to share our combined voices with the local community. Singing in this way is prayerful, for me, whether the repertoire is sacred (medieval and Renaissance church music) or secular (madrigals on all of the classical themes, shepherdesses and romance and so forth.) Singing with the 'bethans has always felt to me like prayer: even when the words we're singing are frivolous, or when they arise out a theology which isn't my own, the act of singing in harmony is for me an act of offering praise.

Thanks for twenty years, y'all. Here's to another concert in 2018!

Worth reading, worth pondering: spirituality that's worth the effort

I read something this week on my friend Gordon's blog which really resonated for me. It's part of his Beginner's Guide to Becoming Episcopalian series. Gordon Atkinson -- some of y'all may know this -- blogs these days at Tertium Squid; he used to blog at Real Live Preacher. Here's the snippet I want to highlight for y'all:

[H]ere’s the deal: do you really want to go to a church for the first time and understand everything that’s going on? Do you really want to walk into the most sacred hour of the week for an ancient spiritual tradition and find no surprises and nothing to learn or strive for? Do you really want a spiritual community to be so perfectly enmeshed with your cultural expectations that you can drop right into the mix with no effort at all, as if you walked into a convenience store in another city and were comforted to find that they sell Clark Bars, just like the 7-11 back home?

I do hope you’ll give this a little more effort than that. Because something wonderful can happen when you stop trying to figure out what you should be doing in a worship service. When you admit to yourself that you don’t know what’s going on, you’ll just sit and listen. Because that’s really all you can do. And that’s actually a very nice spiritual move for you to make.

Reading this, I found myself thinking: right on. I know that Jewish liturgical prayer can be opaque and distancing for people who don't already know what's what. There's a lot of Hebrew. Many of the prayers are very, very old. So are many of the traditions surrounding those prayers. Different communities have different practices: we sit, we stand, we bow, some of us shuckle / sway back and forth like a mother holding a fussy baby. Our worship can be incredibly beautiful and meaningful, but if you don't have access to what's going on, that can feel distancing. I know that.

And yet I love Gordon's point that when one walks into sacred space and sacred community, partaking in the worship of an ancient covenantal community, it's okay to not understand everything from the get-go. What a bummer it would be if entering into communal-spiritual life just happened instantly, in a flash, and there was nothing else to learn -- nothing else to master -- nothing else to strive for. Is that really what we want? Effortless spirituality, the microwave TV-dinner experience of pressing a button and being instantly fed?

Don't get me wrong -- it's important to have moments of immedate access to God and immediate connection with a community. But there's also a lot of spiritual richness in giving oneself over to an experience one doesn't entirely intellectually understand, and trusting that faith and connection and understanding will grow over time. Some things are worth investing time in. Relationships. Parenthood. Delving into a culture or a religious tradition. So it might take a lifetime: so what? What else do you plan to do "with your one wild and precious life?"

Sometimes I think we give our own tradition(s) short shrift: we're willing to have the experience of being unfamiliar, being in beginner's mind, when we travel to someplace foreign and far away, but in our own traditions we want everything to be easy. And yet there's a kind of gift, a kind of magic, which maybe only arises when we allow ourselves to be given-over to a liturgical experience we don't need to entirely understand. Anyway, Gordon says all of this beautifully. Read his whole post here: Let the big people say what needs to be said.

January 22, 2013

Morning blessings with Drew

Drew enjoys the snow. Photo taken earlier this month.

As we make our way out to the car, I can't help marveling at the spectacular crisp cold morning. Half an inch of soft snow limns the trees, the sky is bluest blue, the sun is beginning to tip the mountainsides with gold.

"What a beautiful morning," I say aloud as I help Drew into the car.

"It's a beautiful sunny day," he agrees. This is one of his stock phrases; I think he got it from the narrator on Pocoyo.

"Thank you, God, for this beautiful morning!" I say, because that's how I roll.

"Thank you God for the snow," Drew adds.

I'm charmed, so I reply with another blessing. "Thank you God for my coffee." M'chayyei ha-meitim, I think: blessed are You who enlivens the dead.

Drew isn't finished either. "Thank you God for the trees!"

"Right on," I agree, thinking of Tu BiShvat which will be in a few days. "The trees are pretty awesome."

We drive a bit. Drew eats his waffle. I sip my coffee.

"Thank you God for the earth which is sleeping," I say, as we drive past the snow-covered stubble of a cornfield.

"Thank you God for Daddy," Drew says, getting into it now. "Thank you God for my coat! and my shoes!"

"For the clothes we get to wear, yeah, absolutely," I agree. He doesn't know that thanking God Who clothes the naked is part of our liturgy of standard morning blessings, but I do, and it makes me grin.

There's a pause. I think it's my turn. "Thank you God for me and Drew being together," I offer.

Drew's face crinkles into a smile. "Mommy," he chides, "that's silly."

"Okay," I agree, but I'm thinking: maybe to you, kiddo, but not to me.

January 21, 2013

Another year, another batch of etrogcello

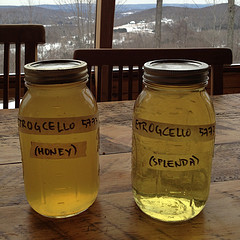

Back in the fall, after Sukkot had ended, I started this year's batch of etrogcello (see curls of peel / prepare to sleep, the post about this year's etrogcello adventure.) This week, with the full moon of Shvat approaching, I decanted the liquid -- now a glorious golden yellow -- into two clean jars, and sweetened one with a splenda simple syrup and the other with a simple syrup which contains honey. The yield is two quart jars, filled almost to the brim with fragrance.

This year's batch.

I haven't tinkered with the color balance of that photograph at all -- that's their real color. (I'm hoping the honey-sweetened one will clarify, though it's possible that it may stay cloudy; I've never tried using honey, so this is a new experiment for me.) And through our dining room windows, behind the two jars, you can see the colors of northern Berkshire winter: the brown of leafless trees, the white of snow and sky, the slate-blue of distant hills.

At this season, in this place, the color palette is muted browns and whites, palest purples and greys. The yellow of the etrog-peel-flavored vodka is startling to the eye. That seems appropriate, somehow: a reminder that when we first made use of this pri etz hadar, this "fruit of a goodly tree," in our Four Species at Sukkot, the world looked like this:

instead of this:

At our Tu BiShvat seder on Friday night (by the way, do you need a haggadah for your Tu BiShvat seder? Here are three of them -- one for adults, one for kids, and one for little kids) I'll invite those who are so inclined to join me in sipping a nip of this homemade etrogcello. It's strong and sharp; it tastes and smells like etrog, that ineffable fragrance which so transports me every time I first open the etrog box before Sukkot begins.

That toast is a stitch connecting this moment in deepest winter, when we honor the trees and their growing-older and our faith that the sap is rising (both literally and metaphorically / spiritually) and spring is coming, to that moment at the end of the harvest season when we prepared for winter's hunkering-down. Beneath the blanket of snow the earth is sleeping, waiting to wake up again. Within our hearts, what from the autumn holidays is germinating, preparing to be born in the spring?

January 20, 2013

This week's portion: Inclusion and service

Here's the d'var Torah I offered yesterday at my shul. Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.

After the first seven plagues, Pharaoh's courtiers advise him to let Moshe and his notables go to worship Adonai. Pharaoh says: fine, just tell me: who's going with you?

And Moshe replies: We will all go, our children and our elders, our sons and daughters, our flocks and herds. Some translations say: We will all go, regardless of social station. Rich and poor, upper-class and lower-class and everything in between.

Pharaoh replies -- in effect -- hell no. Perhaps he's beginning to realize that the Israelites' request to go and worship God a three-day journey away is a ruse, and the real intention is to pack up and depart.

I also wonder whether Pharaoh's anger also arises from distaste at Moshe's inclusiveness. Pharaoh is the epitome of top-down power. He's the kyriarchy. But Moshe's insistence that we will all go -- regardless of age, gender, social station -- negates that worldview.

When it comes to avodat Hashem, all of the community is needed. In order to serve the Holy One of Blessing, we all need to be present. Serving God is something we all do together.

If only the men are empowered to serve God, we're doing it wrong. If only the wealthy are empowered to serve God, we're doing it wrong. If only those who are cis-gendered, or heterosexual, or able-bodied, or neurotypical are empowered to serve God, we're doing it wrong.

Avodat Hashem (serving God) requires all of us. Maybe because each of us is a reflection of God, and only when our entire community comes together can we can see God mirrored in our infinite variability.

Pharaoh says no. The plague of locusts follows, and then a darkness so thick Torah tells us it was palpable. Pharaoh relents and says fine, take your women and children -- but not your herds and flocks, I have to draw the line somewhere. Moshe's answer is: we shall not know with what we are to worship Adonai until we get there.

In a simple sense, he's saying: you have to let us take our animals, because we don't know in advance what we'll be asked to sacrifice. But on a deeper level, I hear him saying that when we enter into service, we have to bring everything: everyone in our community, all that we have, all that we are. We won't know what parts of ourselves will be needed until we get where we're going.

And in a sense, we never "get there" -- we're always going. When we wake up each morning, we don't know what opportunities, what challenges, what blessings lie ahead. We won't know with what we are to worship Adonai in this moment until we reach this moment. And then the next.

I bless each of us: that we be able to bring all of who we are to our service, whether we think of it as serving God or serving our community or serving the world. That we trust that whatever is needed will arise in us. That we find comfort and sustenance in serving the One, together.

(And let us say: Amen.)

January 18, 2013

Halakha: Honoring the Past, Finding Our Way

Among the many highlights of the 2013 OHALAH conference (for me) was the plenary session on Halacha called Honoring the Past, Finding Our Way. It offered a fascinating cross-section of Renewal approaches to halakha through the lens of how different Renewal communities relate to kashrut, preceded and contextualized by some teachings about what we call integral halakha. Here are some glimpses of that session and of my responses to it.

Rabbi Daniel Siegel was the first speaker. He began by citing Rabbi Ethan Tucker's three-lecture series, "Core issues in halakha,"

Rabbi Daniel Siegel was the first speaker. He began by citing Rabbi Ethan Tucker's three-lecture series, "Core issues in halakha,"

which describes the narrowing of the halakhic process which took place

as the Protestant community in Germany in the 19th century petitioned

the government to split funding for different branches, different

churches. "There was a discussion within the Jewish community about

whether or not to do the same thing. Some Orthodox rabbis wanted to stay

in contact with the Reformers, and others wanted to split off."

When the Orthodox community withdrew from the larger Jewish community, in Reb Daniel's words, "they took the leaves out of the halakhic table, leaving a much smaller group." And as a result of that, the halakhic response to change began to shift.

For instance: when women began to practice in ways which hadn't been seen before, there were two different communal responses. One was, "We know the women of Israel are sacred and holy, so how do we take their practice of this custom and bring it inside the mainstream?" And the other was, "How dare they do that, how dare anyone be outside our boundaries, they're wrong and they have to change." I appreciate his point that that kind of strict boundary-enforcing is not necessarily the only authentic response to change.

Over the course of his remarks, Reb Daniel said several things which I remember hearing from him during our halakha classes, and which still resonate for me. Here are a few tastes (boldface / emphasis mine):

Halakha is not a set of decisions, but a conversation. There are many positions possible and they can exist simultaneously. [...]

Halakha is not [about] knowing how to find something in the Shulchan Aruch, but [rather] how to participate in the process of which the Shulchan Aruch is the digest. [...]

There is no such thing as "The" halakha. Halakha does not speak. Halakhists speak. And they respond to questions which are asked of them, usually not by laypeople but by other rabbis.

Reb Daniel articulated his sense that the halakhic process is much better represented by the corpus of sheilot and teshuvot -- questions and responsa; the conversation -- than by the codes and commentaries. It's better represented by the flow, rather than what's static. And then he said:

Our halakha is a tikkun [a healing] on the situation which Ethan Tucker described. Our halakha is insisting that the leaves be put back in the table, the chairs brought back, and we're going to sit down [and be part of the conversation].

We're not starting something new. We're learning the old stuff in a new way so we can bring it into this moment of our existence, and we're doing it in a way that keeps us connected. That's what Reb Zalman means by backward compatibility. And there are issues where we may not be able to do that! But we are insisting that the table be expanded, and that halakhic issues be the issues which face all of us in our lives.

The halakhic process is the effort to link the revelation at Sinai and the redemptive process it set in motion with the details of everyday life. How do I live in this moment in a way that connects me with Sinai and with our ultimate purpose of bringing redemption to this world?

He also argued that "Halakha is the primacy of the ethical. It is our job to make sure halakha rejoins the ethical whenever they diverge." As operating principles for our halakhic process he listed (among others) "eilu v'eilu" ("these and those are the words of the living God" -- in other words, the valuing of a multiplicity of voices), the idea that Torah's paths are paths of peace, and the notion of the enduring (and productive) makhloket / disagreement.

He spoke about ways in which the halakhic process allows us to innovate while remaining consistent with our past and the trajectory of our future. And he ackowledged that "every so often we come to a moment which is so different from the past that the only way to retain the integrity of the halakhic process is to rethink its basic operating principles. This happened 2000 years ago. That's a paradigm shift." Paradigm shifts happen rarely; but just as we were in one 2000 years ago when the Temple fell, we're in one now.

The entire paradigm of how we look at ourselves in the world, not just as Jews but as people, is changing. That's the moment we're in. We need to create a way of doing this process, of connecting the details of our lives, with our entire history and our entire future. We need to be able to do that in a way that takes that change into consideration. We call that integral halakha.

The senior seminar required of all ALEPH rabbinic students is in integral halakha -- I posted a bit about it, a few years ago -- so nothing Reb Daniel said here was surprising to me, but everyone I spoke with agreed that this was a really tight, valuable formulation of the material.

Rabbi David J. Cooper of Kehilla began by saying, "Part of my reason for being up here is to provide food for makhloket [holy disagreement]." He described his understanding of integral halakha, and the value it places on backwards compatibility, as follows:

Rabbi David J. Cooper of Kehilla began by saying, "Part of my reason for being up here is to provide food for makhloket [holy disagreement]." He described his understanding of integral halakha, and the value it places on backwards compatibility, as follows:

As one interprets prior decisions of halakhists and you are faced with adapting these decisions or changing them within your contemporary context, that you should ideally uphold and recognize the integrity of the halakhic process -- its discussions and outcomes -- by locating your present halakhic developments or advancements within that discussion. In practice what this means is that you use the prior halakhic processes and outcomes as a guide even if you are evolving beyond the particular holdings of prior halakhists, and you endeavor to adhere to these holdings as precedents wherever possible – only abrogating them or denying their current validity when contemporary understandings and sensitivities make it ethically or morally impossible to do otherwise.

If your practice conflicts to some degree with prior halakhists, you might seek to demonstrate that what appears on the surface to be discontinuous with a prior halakhic practice is actually continuous if you see it from a more subtle meta-point of view which

As interesting a notion as that may be, he acknowledged, it's not actually the basis on which his particular community makes its choices. He offered an explanation of the origins of the notion of backwards compatibility -- I think of it as being a software term, but he cites an older origin, arguing that it's a term borrowed from the physical sciences, referring to when a new theory pre-empts or supercedes an older theory. He offered an example:

Einstein, even as he superseded and contradicted Newton, had to show why Newton's equations were still so accurate in predicting the orbits of the planets even if Newton's ideas about the force of gravity were shown to be incorrect. In short Einstein's theory had to be backwardly compatible to Newton's. It had to supercede it and yet leave it intact for the limited applications in which Newton's equations still worked. Einstein has to do this because, even if scientific theory had developed in the years since Isaac Newton, the physical character of the universe had not changed at all.

But halakha deals with people and society, and the social universe, unlike the physical universe, does in fact change. The social universe of 1700 was very different from 2012 and from 212... As the social world changes, there have been fundamental changes in how we relate to God and how we hear God's voice, how we define redemption, and how we redeem the world.

We live in a social universe where our very self-definition as human beings has changed. Our relationship to community, individuality, gender has changed. Einstein could supercede Newton and leave him intact as well. But I do not believe that we can leave the decisions of the halakhists intact as Einstein did for Newton. I don't believe we can be authentically backwards compatible.

Having thus "pulled the rug out from under our feet," he moved on to talking about continuity. Our Jewish past may be different from our Jewish present, but it's still our past and still informs who we are and what choices we make. He spoke about eating consciously, a practice which many of his community members identify ex post facto with kashrut. He spoke about the ethical imperative toward inclusivity, of making it possible for as many people as possible to eat at the potluck, and what kinds of practical choices are dictated by that value.

And he spoke about the reasons why his community often makes choices which align with tradition: not because of backwards compatibility, but because of the parameters of the present Jewish community. "This is horizontal compatibility. Compatibility with the present... The past does not get a veto with us, and when it votes, it only gets to do so by proxy -- through community members whose ritual needs are real and present in this moment."

I found Reb David's perspective really valuable -- both because he articulated an interesting challenge to the notion of backwards compatibility (and I appreciate, on a meta-level, the big-tent inclusiveness which allows both of these rabbis to see themselves as part of the same Jewish Renewal community despite differences in halakhic approach and thinking) and because the idea of horizontal compatibility -- ensuring that our practices maintain some continuity with practices of other "kinds" of Jews in other places at this moment -- is a really interesting one to me.

Next up was Rabbi Laura Duhan Kaplan of Or Shalom (who blogs at On Sophia Street). She spoke about kashrut and halakha through the lens of her congregation's dietary practices, which include (though are not limited to): a dairy kitchen which is mostly vegetarian; for ecological reasons, the disallowing of paper plates; the general choice to have potlucks rather than paying for kosher catering; and the maintenance of a garden from which they try to harvest and to cook at least one communal meal each year.

Next up was Rabbi Laura Duhan Kaplan of Or Shalom (who blogs at On Sophia Street). She spoke about kashrut and halakha through the lens of her congregation's dietary practices, which include (though are not limited to): a dairy kitchen which is mostly vegetarian; for ecological reasons, the disallowing of paper plates; the general choice to have potlucks rather than paying for kosher catering; and the maintenance of a garden from which they try to harvest and to cook at least one communal meal each year.

Their communal practice is informed by a variety of principles, among them respect for the Jewish literacy level of the congregation, maintaining a community kitchen where they make food with their own hands and feed one another, commitments to the principles of bal tashschit (don't waste / don't destroy) and avoiding tzar ba'alei chayyim (suffering among living beings, e.g. ensuring that animals are humanely raised and slaughtered), and keeping a traditionally kosher l'pesach kitchen for one week each year "to honor people's felt sense of setting that time apart as something special and holy."

It's important to us that we do not see these rules as any kind of compromise between competing views. Not a compromise with tradition. We see this as an expression of our serious ethical commitments. And we don't think of this practice as a matter of personal choice. But most people experience the imperatives in our principles as coming from a place beyond themselves. These really are ethical principles.

We believe that God is a compassionate being and that we need to be compassionate. Torah tells us God placed us in the world to tend it and care for it, and we take the message of that story very seriously. We don't see our practice as falling short of Jewish responsibility and something we should feel secretly and vaguely guilty about. We see it as a serious and correct understanding of core Jewish responsibilities.

She acknowledged that this is the ideal reality, and that in practice we don't always live up to our ideals. What really happens, she said, is that they make decisions through deliberation and then see what people actually do and then re-evaluate as needed. "In a sense, that's within the spirit of traditional halakha. We have to do things that actually reflect the community of practice. We're elevated by trying to live more consciously by our principles, but if we can't live by it, it doesn't make much sense to say that this is our principle."

Our final speaker was Rabbi Marcia Prager of Pnai Or, who began by acknowledging that "these are issues that tug at our hearts."

Our final speaker was Rabbi Marcia Prager of Pnai Or, who began by acknowledging that "these are issues that tug at our hearts."

She asked a series of questions:

How many of us here are in congregations where there's any conversations about the kashrut of a kitchen? How many of you are in shuls which don't even have a kitchen? How many of you grew up in families where there was a commitment to something called kashrut? How many have taken on a practice which you call something like kashrut? And how many of you know exactly what that is that you've taken on?

It was interesting to see how many hands went up in response to each of these questions, and how many hands went up more than once.

After telling some poignant family stories, Reb Marcia spoke about how she teaches kashrut in her community using many diverse lenses, including her background in cultural and physical anthropology. I was particularly intrigued by this piece of what she said:

The early texts of Torah speak powerfully of our human-cellular memory of moving from early anthropoids into beings of higher consciousness. That's encoded in the early stories of Torah. Those early stories include our memory of emerging from a species that was vegetarian to being carnivorous...

So: what did it mean to become meat eaters and to grow in our ethical understanding of the implications of that? We come to categories of permitted and forbidden which cause us to eat as low as possible on the food chain even if we're going to eat meat.

She cited the way that cattle were treated in the wagon trains which used to move cows from Texas to Chicago in the late 1880s. They couldn't kill a steer every time they needed dinner, so they would put one in the back of the wagon and slaughter it slowly, cutting off pieces and using tourniquets to keep it alive. (The room gave a collective shudder.) And then she juxtaposed that with Torah teaching:

Encoded into our text is a profound commitment to ethical eating. And to understand the pain of animals. Don't we have to care as much about how an animal lived as how the animal died?

She acknowledged that "So many issues inform how we live on whatever this spectrum is that we call kashrut." And she told a wonderful story about the importance of not shaming someone if they bring a dish to a potluck which is, perhaps, not exactly correct according to the parameters of that community's dietary practice.

Toward the end of her remarks, when she was discussing her own community's kashrut practices, she said, "we ask people to adhere to a tradition of ingredient kashrut...so that people can be flexibly and lovingly living more-Jewishly-informed lives." I really like that last phrase: "flexibly and lovingly living more-Jewishly-informed lives." That's something I'd like to foster in my community, too. The notion of encouraging my community to "flexibly and lovingly live more Jewishly-informed lives" resonates with me on levels beyond merely the question of what we do or don't eat.

After the formal panel was over, we moved into small groups to discuss what we'd heard, and then reconvened to share some gleanings with the larger group. I suspect we could easily have spent all day on this, and we didn't even make it beyond kashrut to the second issue which had been suggested for consideration. My breakout group had a terrific conversation about our relationships both with halakha and with kashrut / conscious eating, and also wound up riffing a bit on some of what we'd heard the four speakers say.

I really enjoyed having the chance to see four of my teachers lovingly model some of the multivocality of our tradition and of our Jewish Renewal community.

This was a great panel / conversation -- I'd love to see us do this (or

something like it) each year, exploring halakha and our relationship

with the halakhic process through the lens of a different meta-issue

each time.

Shabbat shalom to all!

January 17, 2013

Join me at the ALEPH Kallah!

I'm delighted to be able to announce that I'll be teaching a workshop at the ALEPH Kallah this summer in New Hampshire!

I'm delighted to be able to announce that I'll be teaching a workshop at the ALEPH Kallah this summer in New Hampshire!

The ALEPH Kallah is the Jewish Renewal Biennial -- a week-long gathering which takes place every other year, a magical week of learning and davenen (prayer) and yoga and meditation and terrific programs and amazing teachers. It's a great way to experience Jewish Renewal: to meet people, have meaningful conversations, experience new modalities of prayer, and engage in learning which feeds your mind and heart and soul alike.

If you're able to get to New Hampshire from July 1-7, I hope you'll consider coming -- and if my class sounds good to you, I hope you'll sign up for it!

Here's my workshop description:

Writing the Psalms of Our Hearts

The psalms are a deep repository of praise, thanksgiving, grief, and exaltation, one of our communal tools for connecting with God. In this class, each of us will become a psalmist. We'll awaken our spirits and hearts by praying select psalms together, warm up our intellectual muscles with writing exercises, and enter into a safe space for creativity as we each write our own psalms. After sharing our psalms aloud and sharing our responses to each others' work, we'll close by davening together once more. At week's end, we'll each take home a compilation of our collected psalms.

Other

Other

classes scheduled for the Kallah will include one on Jewish spiritual

singing, one on quantum physics and kabbalah, one on talking about

Israel, one in Torah yoga / movement, a wilderness Torah experience

(involving hiking and the great outdoors), Jewish meditation, yoga, the

interconnected roots of Judaism and Christianity, Hebrew chanting,

Torah scroll repair / calligraphy, and a terrific class on Jewish and

Islamic mysticism (team-taught by a rabbi and a Sufi) which I took two

years ago and loved.

The Kallah Website includes a listing of all of the classes, along with information about the kids/teens program, opportunities for artists, and opportunities for practitioners of various healing arts.

I've attended the Kallah a few times before, and have blogged about it here (check out the ALEPH Kallah tag for those posts.) Every time I've attended, I've come away feeling spiritually renewed, filled-up with all kinds of wonderful teachings and ideas. I'm excited to be bringing a Torah-poetry lens to the work of writing psalms, and I'm hoping there will be 15 brave / creative souls who will want to do that with me -- but even if my class doesn't sound like your cup of tea, hopefully another of the offerings will.

The Kallah is great fun. I hope some of y'all will join me there. For more information visit the Kallah webpage, or contact the Kallah office at kallahajr@rcn.com.

Photos by Ann Silver, taken at the last Kallah, summer 2011 in Redlands, CA.

January 16, 2013

Rabbi Burt Jacobson on Reb Zalman, davenology, and the Baal Shem Tov

In this workshop we will examine the influence of the Ba’al Shem Tov on Reb Zalman’s life and thought, particularly on Zalman’s creative way of renewing the practice of davvenen. Rabbi Burt will also discuss Zalman’s personal influence on his own life. The class will be taught through lecture, text study, guided visualization, and davvenen practice.

Rabbi Burt Jacobson was my first mashpi'a (spiritual director), and I've been fortunate enough to study the works of the Baal Shem Tov with him. As soon as I saw this session on the schedule, I knew I wanted to attend.

"When I saw the announcement of the theme, mikol melamdai hiskalti (from all my teachers I have learned), I immediately thought of Reb Zalman and the Baal Shem Tov," Reb Burt told us. He said:

I've been a student of the Baal Shem Tov's now for 35 years. And I believe that though he lived in the 18th century he is still a teacher for our time. He provided me with an orientation not just to Judaism, but an orientation to life that serves me every day. I want to talk about the Baal Shem and then talk about parallels I see in Reb Zalman's work.

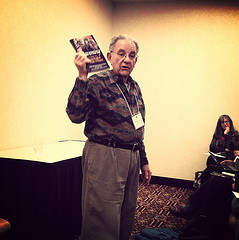

Reb Burt teaches.

He offered some biographical details about the Besht. He was born around 1700. Some fifty years before he was born were the Chmielnitzki pogroms, 1648 and the following years. "These pogroms were among the worst experiences that Jews had ever had since the Fall of the second Temple." And he continued:

In my opinion, those massacres on top of all the dark experiences that Jews had undergone in the years of exile left a traumatic scar on the body of the Jewish people. That scar ruptured the relationship between God and the Jewish people. People thought: we sinned, and God took it out on us through the massacres. There was an abundance of guilt, and in its wake, a lot of asceticism.

I believe that the challenge that the Baal Shem felt was the challenge about how to heal that trauma. How to bring hope, how to bring love. Perhaps the chief tool that the Baal Shem used was prayer. There had never been a movement in Judaism before Hasidism that put prayer so much at the center of Jewish religious life. But it wasn't the old style of prayer. The Baal Shem felt that prayer needed to be reinvented in his time! To make a connection with God that would allow healing to happen.

As I heard him say these things, I started to realize the extent to which there are parallels between Reb Zalman's work and the Baal Shem Tov's. Working and teaching in the aftermath of a communal catastrophe, seeking to help our community heal from trauma, using the tool of prayer (and reinventing the tool of prayer) to make a connection with God which would allow healing to happen -- all of those things sound like Reb Zalman to me, for sure.

The Baal Shem Tov wanted ecstatic prayer to become normative. Ecstatic prayer, Reb Burt suggested, "brings with it a unified vision of reality in which the individual can experience a sense of being loved by God, and being a vehicle to bring love to the Jewish community." And then he transitioned to speaking about Reb Zalman and pointing out some of the similarities between the two men's contexts:

Reb Zalman lived through the Holocaust. He eventually came to see his vocation as the spiritual healing and renewing of the Jewish people. I believe there were two sources of brokenness that needed healing. The effects of post-Enlightenment secularism, which to a large extent drove God out of the Jewish people, or at least the liberal Jewish people; and of course the Holocaust itself.

Together these two sources had ruptured Jewish faith and belief. For so many people, God had disappeared from the center of Jewish life. Reb Zalman felt that Jewish prayer needed to be reinvented.

A packed room listens attentively.

Some ten years ago, Reb Burt interviewed Reb Zalman for the book he's writing on the Baal Shem. And he asked, what did the Besht give you personally? And here's the answer which Reb Zalman gave him -- drawing on a Besht teaching which in turn arises out of the story of Noah, the flood, and the ark:

The Baal Shem has had a great deal to do with the software of my theology of prayer. I learned from him how every word in the liturgy can disclose more and deeper meanings if only you allow this to happen. The Torah states that God told Noah to build an ark to carry life through the devastation of the Flood. And he was also told to make a window-light for the ark. Well, the Hebrew word for ark (teivah) can also mean 'word.' So the Besht took the Biblical verse to be a call to worshippers to leave the external world and to fully enter and immerse themselves in each word of prayer.

But this was not enough. The worshipper was also to make a window-light (tzohar) for each word, to open the word to the illumination of the inner light of the soul. It was a call to enter into the Divine through the sacred language of tradition, to leave the 'objective' world and enter fully into the so-beingness of God.

Imagine yourself in a theater. Most of the people in the audience just sit there and passively watch the action ufolding on stage. Only the actors are fully engaged in the drama. That is what the act of prayer is to the Besht. He calls us to be on stage, to embody the script at all levels of our being. Then the davening becomes one's own drama, one's own love and longing, one's own rendezvous with God.

I love the idea that going to services can either be a matter of sitting in a theater passively, or being the actors on the stage who are inhabiting the words of their scripts every time they speak them aloud. Imagine delivering every line of a prayer with all of the heartfelt feeling that a talented actor would bring to a meaningful role. Imagine really embodying the script really feeling what the prayer means, and then reciting it aloud!

Reb Burt continued:

This becomes the task of congregational prayer. Making a window in the

word, as Noah was commanded to make a window in the ark. To illuminate

the word.

What does that mean? It means that we can't be passive when we're davening. That we have to look at each word -- the Baal Shem actually says each letter! -- and go inward, uncover the experience that we have had at some time in our life that somehow resonates with this particular word, and we use our imagination to take that memory and infuse it into the word on the page. So that the word now becomes us, and there's no separation between us and the word.

Somewhere in there was an amazing guided meditation, and also an exercise where we took three minutes of silence to focus on our experiences of being loved, and then we prayed the first line of the ahavah rabbah prayer ("with a great love You have loved us, Adonai our God...") aloud. I closed my eyes and thought about being loved, and was immediately filled with sense-memories of my sweetie and our son showing me that they love me. When I prayed the prayer, after that, I thought: the wild enthusiastic hugs of my three-year-old: that's God's love. Holy wow.

Toward the end of the session, Reb Burt shared with us a quote from Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, in Man's Quest for God, commenting on the same teaching (about going into the teiva, the ark / the word) which the Baal Shem had commented on:

There need be no prayerful mood in us when we begin to pray. It is through our reading and feeling the words of the prayers, through the imaginative projection of our consciousness into the meaning of the words, and through empathy for the ideas with which the words are pregnant, that this type of prayer comes to pass. The word comes first; the feeling follows...

Unless one knows how to approach a word with all the joy, hope, or grief that he owns, prayer will hardly come to pass. The words must not fall off our lips like dead leaves in the autumn. They must rise like birds out of the heart into the vast expanse of eternity. To begin to pray is to confront the word, to face its dignity, its singularity, and to sense its potential might. It is the spiritual power of the praying person that makes manifest what's dormant in the text.

"There ned be no prayerful mood in us when we begin to pray:" indeed. As with creative life, as with writing poetry, as with making love, when one begins the act at hand, the feeling comes -- and if one waits until the feeling is there, the act might never happen. And I love Heschel's notion that the words of our prayers must "rise like birds out of the heart into the vast expanse of eternity"!

Anyway: this session was one of the highlights of the conference for me. (And it was a particular joy to have Reb Zalman in the back of the room, occasionally calling out with an addition or a correction.) I'm grateful to have had the chance to listen to Reb Burt teach not only about the Besht, but also about how the Besht's life and work are paralleled in the life and work of Reb Zalman, the teacher of my teachers.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers