Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 200

February 5, 2013

February

The skies are grey. The streets are streaked with mud, and so are the sidewalks, and so are the cars. I lean on my car to toss something in the backseat and when I move away, my jeans and boots are smudged white with road salt. The excitement of early winter -- the first snowfalls, the holiday parties, the twinkling Chanukah candles -- are long gone. And we all know that no matter what the groundhog saw, even if the full moon of Shvat is now behind us, winter won't unclench for quite a while.

It's February. And around these parts, our eyes get starved for color. At least mine do. Where I grew up, it's greening already by now. I grow weary of this palette. There's a muted beauty to this season -- the hills all brown and grey and white, bare trees and distant conifers and patches of ice and snow -- but it's pale, and sometimes its subtlety eludes me. Afternoon sunlight, when the clouds part, is thin. And the sun still sets early -- not as early as it did six weeks ago, but early still. Spring feels so far away.

This is the season when I find myself standing idly in the hair products aisle of the drugstore, distracted by the glossy pictures on the covers of the boxes of hair color. I turn the names over on my tongue like butterscotch candies. Light auburn. Reddish blonde. Burgundy plum. Would I wake up feeling more vibrant, would the world be more vivid and bright, if I colored my hair for the season? In the end I purchase a bottle of nail polish instead: a little color, a little sparkle, but when it chips it's easy to remove.

I've lived in New England for twenty years now. I recognize the symptoms of The Februaries when they come on, and I know techniques for combating this particular brand of malaise. I feast my eyes on my red boots and my purple peacoat, treat myself to hot baths and to luxurious fires in the fireplace, purchase potted amaryllis or daffodil bulbs for my home office and my synagogue office so that I can drink in that hint of green, that promise of new life. I seek out strong flavors. I change things around: remove my home office rug and ponder what I might want there in its place.

The people who make catalogues are attuned to these rhythms, too. I glance through one which has come to our mailbox, and marvel at the canniness of showing photos of graduated cooking bowls in shades of lemon and lime, throw pillows in shades of effervescent spring chartreuse and bright summer sun. I come up with a zillion house projects, ideas for organizing and clearing the clutter. If I gardened, I'd be hip-deep in fantasies about seeds; as it is, I make stacks and piles, to-do lists, dreams of how I could brighten and organize.

What is it I'm really thirsty for during this slow short month of deepest midwinter? Color and spice. Experiences to saturate my senses. New growth and new potential. Windows clear and sparkling instead of fogged with condensation or streaked with salt. Some days, when I'm out at mid-day, I drive with my hat and gloves on so I can feel the fresh air on my face. This season requires patience. And the willingness to cobble together a patchwork of cures: dark green kale dressed with bright tangy lemon, the last of the sweet clementines, the fuzz of my son's red moose blanket sleeper as we cuddle before sleep.

February 4, 2013

After the week of shiva, what then?

This is something I've been working on in my capacity as a congregational rabbi. I'll be sharing it with my synagogue community. But I wanted to share it here too. This blog is part of my rabbinate, and I'm blessed to be in relationship with "internet congregants" who are spread pretty far and wide.

If you've just found this blog through searching for resources for the end of shiva, I welcome you to Velveteen Rabbi, and I hope that what follows is helpful to you.

So you're approaching the end of shiva. That first week of mourning after the funeral, after the first mourner's kaddish, after the unthinkable act of shoveling a spade-ful of earth and hearing it thud on unvarnished wood. Shiva means seven, the number of days of this first stage of grieving. One week: the most basic unit of Jewish time. After those seven days, a mourner enters the stage called shloshim, "thirty," which lasts through the first month after burial. But what does entering into shloshim mean? How does it, might it, have an impact on your life?

In the tangible world, the move from shiva to shloshim can have palpable implications. Traditional Jewish practice places a variety of restrictions on mourners during shiva -- for instance: not wearing leather shoes, sitting on the ground or on a low stool (closeness to the earth is a sign of humility and mourning), not going to work, not engaging in physical intimacy. All of these restrictions are lifted during shloshim.

For contemporary liberal Jews who do not consider themselves bound by traditional halakhot (laws / ways-of-walking), the restrictions and their abeyance may or may not have meaning. You may not have given up leather or sex or anointing yourself with perfume or listening to music this week. But the psycho-spiritual shift of moving from shiva to shloshim is still significant. The shift from shiva to shloshim is all about expansion.

During the first week of mourning one's life may contract to a very small space. Perhaps you haven't left the shiva house at all. Or even if you've gone in and out of your home, you may have felt constricted, your life seemingly shrunken. Once shiva has ended, it is time to start expanding again. Open yourself to seeing more people. Allow yourself to immerse in your work life again. Expand your self-perception: you are not only a mourner, not only someone who grieves, but also someone who lives, works, struggles, and loves.

This may feel impossible. If it does, that's okay. Just know that our tradition believes that it is good for a mourner to try to open themselves to life again after that first most-intense week of grief. Your sorrow may ebb and flow. You may experience times when you think you're close to okay again, and times when the floodwaters of emotion threaten to swamp you. Keep breathing. The emotional rollercoaster is normal. You won't always feel this way, but -- as the saying goes -- the only way out is through.

If you've been burning a shiva candle all week, your candle will

naturally flicker and gutter and run out of fuel as the week of shiva

ends. (The candle is designed to last for seven days; that's what makes it a shiva candle.) When the candle extinguishes itself, that may feel like another blow, another loss. Remember that the

candle is only a candle: a symbol of your mourning, but not a barometer

of your spiritual state or of your loved one's presence.

You can still talk to your loved one, if there is meaning for you in that practice. You can talk to God. You can pray or meditate or sit in your silent car and wail -- however you can best express whatever you're feeling. You might try writing a letter to your loved one at the end of shiva, telling them where you are and how you are as the first week of active mourning comes to its end. (What you do with the letter is up to you: save it? burn it? shred it and use the paper to mulch a new tree?)

Above all, be kind to yourself. Pay attention to what your heart needs.

This second stage of mourning lasts for one month, the time it takes for the moon to wax and become full and then wane again. This is an organic cycle, a mode of measuring time through observing the ebb and flow of the natural world. Just as the moon grows and shrinks, so our spirits and our hearts experience times of fullness and times of contraction. The end of shloshim is a time to begin looking toward fullness again. We trust that after the moon has disappeared, she will return; we trust that after our lives have been diminished by loss, light and meaning will flow into them again.

If you are moving from shiva into shloshim: I bless you that the transition should be what you need it to be. May this ancient way of thinking about mourning and the passage of time be meaningful for you; may time soothe your grief. One traditional practice is to mark the end of shiva by going for a walk around the block -- a symbolic step out of the closeness of your home, into the wide world around you. (See Ending Shiva by Rabbi Peretz Rodman.)

If you are moving out of shloshim, I offer you the same blessing: may this transition be what you most need. For those who feel the need for a ritual to mark that shift, I recommend this Leaving Shloshim Ritual by Rabbi Janet Madden. (Ritualwell has a wide variety of materials relating to mourning and bereavement, so if that ritual isn't what you need, feel free to browse.)

May the Source of Mercy bring you comfort along with all who mourn.

February 3, 2013

This week's portion: A Special Transmission at Sinai

Here's the d'var Torah I offered yesterday at my shul. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

Imagine the scene: Mount Sinai is wreathed in smoke, the mountain trembles, and God's voice rings out like thunder. The whole people is standing together at the bottom of the mountain, and everyone hears God's voice directly.

It's an amazing moment. But it's not "The Ten Commandments," Charleton Heston-style. Ten Commandments is a bit of a misnomer. That name comes from the translators who created the King James Bible in 1611 C.E. In Jewish tradition we call these the Aseret ha-Dibrot -- the ten statements, utterances, sayings.

When the Second Temple stood, these statements were read as part of daily prayer. In Talmudic times, the rabbis consciously made a decision to stop that recitation. They worried that too much emphasis on these statements might lead people to mistakenly believe that these were the only mitzvot, and neglect the full 613.

These aren't our only mitzvot. But they are powerful, and the teaching that they came directly from God to us -- instead of through Moshe as an intermediary -- highlights the fact that these statements are special in some way. What's so special about this transmission?

This week's Torah portion is called Yitro, named after Moses' father-in-law. Yitro was a Midianite priest. And yet his name graces this parsha where the Aseret ha-Dibrot appear! Maybe one thing that's special is, we received them when we allowed ourselves to be open to the wisdom of someone from outside our community, outside our camp.

Midrash holds1 that these ten statements were special because God spoke them all simultaneously:

'God spoke all these words.' This teaches us that God spoke the Aseret Hadibrot in one utterance — something impossible for creatures of flesh and blood. If so, why then is it said 'I am the Lord your God,' 'You shall have no other Gods,’'and so on? It simply teaches that the Holy One, blessed be God, after having said all of the Aseret Hadibrot in one utterance, repeated them, saying each commandment separately [so that we could understand.]

Other sages in our tradition2 see the Aseret ha-Dibrot as parallel with the ten statements of creation from Genesis -- every "and God said let there be..." This interpretation requires some interpretive gymnastics, but leads to some beautiful ideas.

For instance: the fifth statement of creation is "there shall be luminaries in the sky," and the fifth commandment is "honor your father and mother," which teaches us that our parents are like the sun and moon, sources of light in our lives.

Or: the ninth utterance of creation is "let Us make humanity in Our image," and the ninth "commandment" is "do not bear false witness," teaching us never to testify falsely against one who bears the divine image -- which is to say, any human being, because each of us is made in the image of God.

One rabbinic interpretation3 holds that the Aseret HaDibrot are general principles representing the two main categories of mitzvot in Torah: mitzvot bein adam l'makom, between a person and God, and mitzvot bein adam l'chavero, between two human beings. The first five statements speak to our faith in God and our obligations toward God; the second five speak to our relationship to each other.

If you're paying close attention to the numbering, you may notice something surprising about that assertion. In our usual numbering, "Honor your father and your mother" is number five -- but the first five statements are supposed to guide our relationship with God, not with other people. How can we understand this?

The rabbis teach that our parents are our creators, and stand in a relationship to us which is a microcosm of God's relationship to us. When we honor our parents, we are also honoring God. For most of us, it's a beautiful notion.

But we know that some parents don't merit this honor. And those who abuse their children may use this Biblical verse as a crutch to support the damage they inflict. For this reason, I think we can read the fifth commandment broadly: honor the mentors and teachers, the grandparents, the loved ones, and hopefully the parents, who helped to shape who you are and who you hope to become.

I love that we say "yes" before we've heard the details of what God's asking...and that we answer yachdav, as one. Later in our wanderings we'll be pretty fractious. But in this moment, we're truly one community: one heart, one will, one desire. Our desire is to live righteously, to be in covenant with God, to be holy. We say "yes." What can you say "yes" to in your spiritual life, and your spiritual practice, today?

1 Mekhilta de Rabbi Ishmael

2 Zohar( (see The Ten Utterances of Creation Parallel the Ten Commandments)

3 Sefer ha-Ikkarim, Rabbi Joseph Albo

February 1, 2013

Best-laid plans

Friday begins with a hitch in our plans: my car won't start. So Drew and I won't be going in to town for school or work. We're staying home and waiting for the tow truck instead.

Midmorning it occurs to me that we have flour and yeast and water. Instead of going to the A-Frame as we usually do, we can bake our own challah!

Drew's willing to be lured away from the cartoons and the marble run game for a while. He pulls his footstool into the kitchen. He stirs the bowl a bit, announcing excitedly that he is helping.

A few hours later, when the dough has risen, I invite Drew back in. He seems to like patting the flour (which he calls, adorably enough, "flowers") and trying to roll snakes of dough beneath his hands.

Braiding seems like too much of a challenge for him, so I braid one big challah and one tiny one, and with the other pieces we make a twist and a spiral roll, which we set to rise.

While the smaller challot are baking, we read It's Challah Time! -- a longtime favorite -- and he takes obvious pleasure in being able to say, "I did that!" every time we come to a step in which he participated.

Once the first batch is out of the oven, I say hamotzi and we share a little challah roll. It's delicious: light and fluffy, tearing apart like the dinner rolls they used to serve at the Barn Door when I was a kid.

But as yummy as the bread is, Drew's obvious delight is even more so. (To be fair, he's equally delighted by the appearance of the mechanic and his big tow truck later in the day. Large vehicles are super-exciting to this three-year-old boy.)

As sundown approaches, I put one of our small braided challot beneath a napkin and tuck candles into our candlesticks, extra-excited about making the blessings with Drew over Shabbat challah we made with our own hands.

Of course, because nothing ever goes as one anticipates, it turns out at dinnertime that he doesn't like our challah. It seems to have become denser, now that it's cooled; it's not as soft and airy as the one the baker makes. He refuses to eat it. And then, for good measure, refuses to eat anything else, and blithely tells me he's done with dinner.

Oh, well. I'm still happy we made challah together. Even if he didn't eat a single Shabbat bite.

The Kallah brochure is on its way!

The brochure for this summer's ALEPH Kallah -- the Jewish Renewal biennial -- is at the printers'. And it's also available for download as a pdf if you don't want to wait!

Find it at the Kallah website. Join us in New Hampshire for an amazing week of learning, playing, praying, singing, connecting, and having your heart opened to the divine within and around us.

(And if you're interested in writing psalms, I hope you'll consider signing up for the class I'm teaching, "Writing the Psalms of Our Hearts" -- read more about it in this post from last month.)

5 ways to celebrate Purim

Now that Tu BiShvat is behind us, the next festival on our radar is Purim. In preparation for our coming holiday of masks, costumes, food, and merriment, I've shared a post at my congregational blog about five things you can do to celebrate Purim wholly this year. It's here: How to Celebrate Purim in 5 Easy Steps.

A few of the items on that list are geared toward my local community. For instance: the first one is "listen to the megillah," and if you're local to me, you are welcome to do that at my synagogue on Saturday night February 23! And the second one is "give to the needy," and it happens that Purim afternoon coincides with the one Sunday a month when my community cooks meals for 100+ homebound senior citizens in North Adams, so if you're local to me, you are welcome to come and help out with that. But these five ways of celebrating Purim are possible no matter where you live.

Anyway, if you're looking for tips on how to make Purim fun and meaningful, check out the post over there. Shabbat shalom, y'all.

January 31, 2013

Imperfect poetry on the theme of light

RADIANT

like a newly-minted rabbi

dazzled from the transmission

as dawn, her fingers smeared

with palest raspberry

like heat in a tile floor

warming me to my bones

as the sun, so bright

I blink away tears

like a lightbulb

electrified by current

as a crescent moon peeking

slyly around night's doorframe

like snow, sparkling mica-bright

in an unexpected wind

as a three-year-old, bounding

to knock me down with a hug

This week's imperfect prose prompt from Emily Wierenga is "light." The idea of light led me to radiance, and radiance made me think of our son. It's a cliché to compare a child's radiance to any other source of radiance I can think of -- so I figured instead of trying to avoid the predictability, I'd play with it a little. The resulting poem was fun to write. I hope it's fun to read, too.

You can check out other people's offerings on the theme of light in the comments on this post: imperfect prose on thursdays: light.

January 29, 2013

One of my mother poems in the Jewish Journal

My thanks are due to the editors at The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles for publishing my poem Mother Psalm 6 in their 22-28 Tevet / January 4-10 print edition. (I can't link to it online because they don't archive their previous print editions -- just "this week" and "last week," and January 4-10 is now longer ago than that.)

That poem previously appeared in Calyx, Vol. 27 no. 2, Summer 2012. And it will be part of my forthcoming collection of mother poems, Waiting to Unfold, due from Phoenicia later this year.

This is one of my favorite poems in the collection, and I'm gratified that multiple editors have chosen it for publication, too. (It's the one that begins "Don't chew on your mama's tefillin," and it appeared on this blog in its earliest form when it was first written: it was then called Mother Psalm 7.)

Thanks, Jewish Journal poetry editors!

January 28, 2013

Eulogy for a child with Canavan's

I don't usually share eulogies here. They are personal, and this blog is public. But this is an unusual situation, and I think the eulogy might be helpful to others, so I've removed identifying material in order to share the essence of what I offered at a funeral a few days ago. If these words are useful to you, you are welcome to adapt them.

If you got here by googling Canavan's Disease, please know that there are informational links at the bottom of this post.

When a child is born, we rejoice. We imagine possibilities. Our minds run away with us, providing us with dreams and imaginings of wonders we hope the child's life will hold.

When this child was born, no one imagined that his life, and his parents' lives, would be circumscribed by a neurodegenerative disorder... nor that he would come to be such a ineffable presence in the lives of those who knew him, cared for him, and loved him.

Because of the dangers of Canavan's, this boy was never alone. His parents, and later his nurses, took constant shifts in caring for him. He communicated with his eyes and, for a time, with sounds. When he was in his parents' arms or enjoying therapy his smiles and laughter brightened the room.

His was not the life his parents might have dreamed before he was born, but it was his own, and he lived it wholly. He experienced love in the touch of caring hands and the attention diligently paid to the apparatus of his care.

His parents, and his caregivers, experienced a deep connection with him. And they knew that connection was reciprocated, and they knew that connection was real. Every time he fought his way back from another illness, another hospitalization, they knew that -- in his mother's words -- "he still wanted to be here."

His parents knew him without words. They teach us that we can know each other beyond words, and listen deeply past the words we do hear, to something deeper, more ineffable and more lasting.

The same was true of his nurses, his caregivers, physical therapists, music therapists, those who lovingly massaged his body to help preserve his muscle tone, the teachers who came to offer him a window into the wider world. When he lay on his bed in the sun, his parents called it "his beach." Once his health became too poor for him to risk the trip to these hills, his parents preserved his room here intact, a place for their son in this town they called "the home of their hearts."

I was blessed to spend an afternoon with this young man and his family last month. I sang him the lullabies I sing to my own son, and his eyes stayed on mine. I experienced his quiet presence in the room, and the sweetness of his neshama -- his soul -- was clear without any words at all.

I am humbled by this child's life, and by the boundless well of love and compassion which his parents and his caregivers expressed every day through a million acts of caring and nurturing.

He lived, and struggled, and was loved. He experienced the world from his own unique vantage. In the wake of his death, there is grief. Nothing we can offer will soothe the empty place where he used to be.

May his soul soar free, no longer fettered by limitations or by suffering. And may those who loved him find comfort in the knowledge that his suffering has ended, and that in caring for him so lovingly, they epitomized some of the best of what humanity can be.

For more information:

National Tay-Sachs and Allied Diseases

Center for Jewish Genetics: Canavan's Disease

January 25, 2013

Tu BiShvat bounty

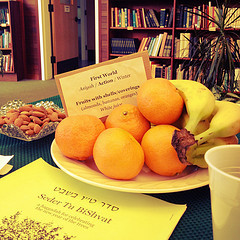

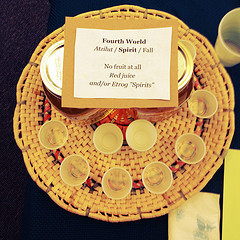

Fruits representing all four worlds:

assiyah (action / physicality) represented by fruits with shells or rinds: bananas and oranges and almonds.

yetzirah (emotions) represented by fruits with hard pits: dates, cherries, olives.

briyah (thought) represented by fruits which are soft all the way through: apples (and grapes, even though they're vine fruit.)

atzilut (essence) represented by etrogcello / strong etrog-infused spirits.

I didn't expect a big crowd for Tu BiShvat. I set up two tables and assumed that would do. Instead we had four tables' worth of people! We had to keep pulling tables out of the storage room and hastily adding them to the line. Some folks probably came because this is the first Shabbat potluck we've had in 2013. Others probably came because they were interested in Tu BiShvat. There's no telling what made each person or family decide to show up on this very cold Berkshire night, but I'm glad they did.

I abbreviated our adult haggadah a little bit -- some of the little kids (including mine) were running gleefully around the building, others were sitting at the table but not necessarily paying much attention, and I could tell we didn't have the focus for everything in there! Still, it was lovely. One of my congregants read the Marge Piercy poem about Tu BiShvat which I love so much. Others took turns reading little explanations of the four worlds. We blessed and drank, blessed and ate.

And then there was a potluck feast. (All Drew ate was a few bites of challah, a couple of grapes, and a handful of Thin Mint cookies. Well, he's hardly the first little guy to have so much fun running around the synagogue he couldn't manage to sit still to eat anything.) And when we were done eating, as the kids ran and yelled and played, I handed out copies of "Brich Rachamana" (the "Sanctuary" melody) and we sang that as our abbreviated birkat ha-mazon.

And after that I brought Drew home and bundled both of us into PJs. I'm looking forward to sleeping, just like the trees, in tonight's long winter dark. Happy Tu BiShvat to all!

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers