Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 196

March 20, 2013

9 Nisan: Asking

The oldest editions of the Mishnah record 3 questions asked at the Passover seder:

Look, how different this night is from all other nights!

On all other nights, we dip once, this night twice.

On all other nights, we eat chametz or matzah, this night – only matzah.

On all other nights, we eat meat roasted, fried or cooked, this night only roasted.

(Okay, the semanticists among you may argue that this really doesn't involve any questions at all -- it's an exclamation and three statements -- but roll with me here.) The Mishnah is the essential source text for rabbinic Judaism. It was originally oral tradition; it was written down around 200 C.E. (Learn more: Mishnah - My Jewish Learning.) The oldest Mishnah manuscripts are handwritten. Once the questions entered print, though, they changed a little bit:

They fill a second cup for him. At this stage the son questions his father.

If the son is unintelligent, his father instructs him to ask, 'Why is this night different from all other nights?'

On all [other] nights, we eat chametz or matzah, [but] on this night, [we eat] only matzah.

On all [other] nights, we eat all kinds of vegetables, [but] on this night, [we eat only] bitter herbs.

On all [other] nights, we eat meat roasted, stewed or boiled, [but] on this night, [we eat] only roasted [meat].

On all [other] nights, we dip [vegetables] once, [but] on this night, we dip [vegetables] twice.

And according to the son's intelligence, his father instructs him.

The Gemara -- the commentary which, along with the Mishna, makes up the Talmud (learn more: Gemara - My Jewish Learning) -- expands on this idea. It tells us that if the son has the wisdom to ask, he asks. If not, then the wife (of the person leading the seder) asks. (Their assumptions that the seder-leader was inevitably male and married were reasonable at that moment in time.) And if not, the Gemara tells us, the seder-leader asks himself.

I absolutely love that. Asking questions in order to more deeply understand the seder, and in order to have the emotional and spiritual of asking, is so central to the seder that one can even ask oneself the questions if one has to.

Of course, neither of those sets of questions is exactly like the ones we know now. In the Geonic period (6th to 11th centuries), the questions were changed once again, to the version we still sing today.

מַה נִּשְׁתַּנָּה הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה מִכָּל הַלֵּילוֹת?

שֶׁבְּכָל הַלֵּילוֹת אָנוּ אוֹכְלִין חָמֵץ וּמַצָּה. הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה כֻּלּוֹ מַצָּה:

שֶׁבְּכָל הַלֵּילוֹת אָנוּ אוֹכְלִין שְׁאָר יְרָקוֹת הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה מָרוֹר:

שֶׁבְּכָל הַלֵּילוֹת אֵין אָנוּ מַטְבִּילִין אֲפִילוּ פַּעַם אֶחָת.

הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה שְׁתֵּי פְעָמִים:

שֶׁבְּכָל הַלֵּילוֹת אָנוּ אוֹכְלִין בֵּין יוֹשְׁבִין וּבֵין מְסֻבִּין. הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה כֻּלָּנוּ מְסֻבִּין:

Why is this night different from all other nights?

On all other nights we may eat either hametz or matzah; tonight, only matzah.

On all other nights we may eat a variety of green vegetables; tonight, we eat maror.

On all other nights we don't dip our foods even once; tonight, we dip twice.

On all other nights we may eat either seated or reclining; tonight, we recline.

The Four Questions are one of the most familiar and iconic elements of today's seder, and they've had this shape for a long time, but this wasn't their original shape. This is at least the fourth iteration. I love being able to trace their evolution, to see when the bitter herbs entered the picture, and when the roasted meat left the page.

The roasted-meat question arose out of the tradition of bringing a lamb to the Temple for sacrifice. Intriguingly, it didn't leave the liturgy as soon as the Temple fell. When the Mishnah first appeared in print, the Temple had been gone for more than 100 years, but the questions recorded then still preserved the memory of that practice. By the Geonic period, enough time had elapsed that it didn't make sense to feature a question about that roasted sacrificial meat. But -- perhaps to preserve the structure of four questions -- those sages added a question about reclining, instead.

The roasted-meat question arose out of the tradition of bringing a lamb to the Temple for sacrifice. Intriguingly, it didn't leave the liturgy as soon as the Temple fell. When the Mishnah first appeared in print, the Temple had been gone for more than 100 years, but the questions recorded then still preserved the memory of that practice. By the Geonic period, enough time had elapsed that it didn't make sense to feature a question about that roasted sacrificial meat. But -- perhaps to preserve the structure of four questions -- those sages added a question about reclining, instead.

Questions matter. The act of questioning is central to the experience of seder, and central to being a Jew. Some of us today ask ourselves a fifth question: from what do you hope to be liberated in the year to come?

I've come to think that a lot of the time, the questions are more important than their answers. Or: maybe what's important is the experience of questioning. Of caring enough to ask: how did this start? Why do we do it this way? What does it mean to say that our ancestors were slaves to a Pharaoh in Egypt, and the Holy Blessed One led us out of there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm? I don't necessarily need answers. (And I know that my answers change from year to year, as I grow and change.) I just need to always be able to ask.

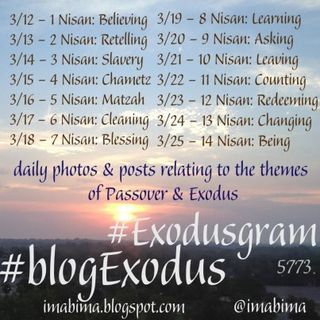

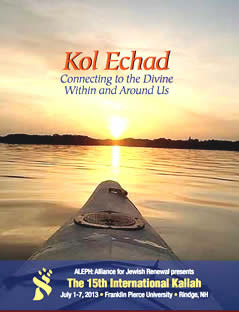

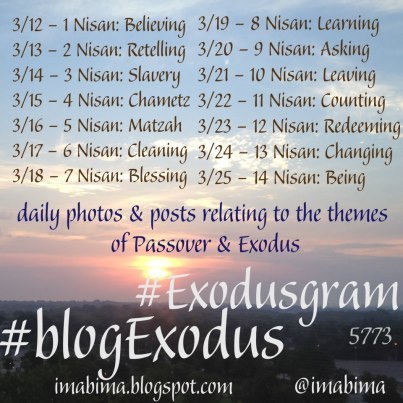

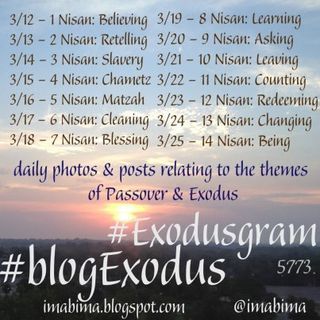

This post is part of #blogExodus. Follow other posts on the path to Pesach via the #blogExodus and #Exodusgram hashtags!

March 19, 2013

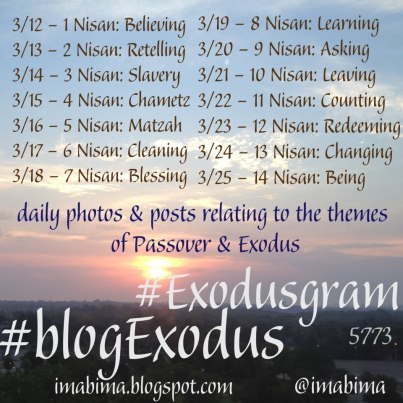

Getting excited about the ALEPH Kallah

I just received my brochure for the ALEPH Kallah, and it's gorgeous -- I'm getting really excited about this amazing week of learning, davenen, and community. The brochure is also available for download as a pdf:

You can download the brochure at the Kallah website.

The class I'm teaching meets in the afternoon, and here's the description of that class:

Writing the Psalms of Our Hearts

The psalms are a deep repository of praise, thanksgiving, grief, and

exaltation, one of our communal tools for connecting with God. In this

class, each of us will become a psalmist. We'll awaken our spirits and

hearts by praying select psalms together, warm up our intellectual

muscles with writing exercises, and enter into a safe space for

creativity as we each write our own psalms. After sharing our psalms

aloud and sharing our responses to each others' work, we'll close by

davening together once more. At week's end, we'll each take home a

compilation of our collected psalms.

I'm trying to decide which of the morning classes I want to sign up for. R' Elliot Ginsburg's Sovev U'memalei: The Divine Within Us, Between Us, and Beyond All Our Namings? (I loved learning with Reb Elliot in rabbinic school, and I've missed his Hasidut classes.) Karen Barad and R' Fern Feldman's Infinity, Nothingness, and Being: Running and Returning, an Exploration in Quantum Physics and Kabbalah? R' Jeff Roth's Jewish Meditation Practices for an Awakened Heart? R' David Zaslow's Roots and Branches: the Jewish Roots of Christianity? So many good choices! (And there are many other morning offerings as well -- these are just the ones I personally find most tempting.)

I hope you'll join us in New Hampshire for an amazing week of learning, playing, praying,

singing, connecting, and having your heart opened to the divine within

and around us.

8 Nisan: Learning

עֲבָדִים הָיִינוּ לְפַרְעֹה בְּמִצְריִם. וַיּוֹצִיאֵנוּ יְיָ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מִשָּׁם, בְּיָד חֲזָקָה וּבִזְרוֹעַ נְטוּיָה, וְאִלּוּ לֹא הוֹצִיא הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא אֶת־אֲבוֹתֵינוּ מִמִּצְרַיִם, הֲרֵי אָנוּ וּבָנֵינוּ וּבְנֵי בָנֵינוּ, מְשֻׁעְבָּדִים הָיִינוּ לְפַרְעֹה בְּמִצְרָיִם. וַאֲפִילוּ כֻּלָּנוּ חֲכָמִים, כֻּלָּנוּ נְבוֹנִים, כֻּלָּנוּ זְקֵנִים, כֻּלָּנוּ יוֹדְעִים אֶת־הַתּוֹרָה, מִצְוָה עָלֵינוּ לְסַפֵּר בִּיצִיאַת מִצְרָיִם. וְכָל הַמַּרְבֶּה לְסַפֵּר בִּיצִיאַת מִצְרַיִם, הֲרֵי זֶה מְשֻׁבָּח:

We were slaves to a Pharaoh in Egypt, and the Eternal led us out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. Had not the Holy Blessed One led our ancestors out of Egypt, we and our children and our children’s children would still be enslaved. Therefore, even if all of us were wise, all-discerning, scholars, sages and learned in Torah, it would still be our duty to tell the story of the Exodus.

(--from the traditional haggadah)

Even if all of us were wise, all-discerning, scholars, sages, and learned in Torah...

That's always been one of my favorite lines of the haggadah. Even if all of us were all of those things -- if gathered around the table were wholly enlightened beings, with immeasurable depth and breadth of knowledge; if we were scholars and sages, rabbis and mystics, versed in Torah and commentary from throughout the ages -- it would still be incumbent on us to tell the story of the Exodus. Telling that story would still be our sacred duty.

From this I discern that what matters is the telling. Not just our intellectual knowledge of the story, but the act of retelling the story each year: that's what constitutes us as a people. We are the people who every year pause to remember and re-enact the story of the Exodus. We tell ourselves into the story. We assert that the Holy Blessed One lifted us -- not (just) our ancestors, but us -- out of slavery with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm.

Every year we tell the same story, sing the same songs, read the same prayers. (Okay: some of us are more prone to change-ups and innovations than others. For some of us, the haggadah may shift and grow and change each year. But the central story is always the same.) And every year is different, because we are different. We bring ourselves to the table: our lives, our stories, our emotions, our experiences. This year's seder won't be exactly like the last.

The seder is a teaching tool, and each of us is a learner. No matter how wise we are, how discerning. No matter whether we are preschool children, or scholars with decades of Torah study under our belts. We come to the seder willing and ready to learn. Are there details of the story we hadn't noticed before? New interpretations we hadn't seen? Emotional resonances we hadn't considered? There is always something to be learned.

This post is part of #blogExodus. Follow other posts on the path to Pesach via the #blogExodus and #Exodusgram hashtags!

March 18, 2013

7 Nisan: Blessing

In English the word blessing is a gerund, an ongoing-action word. I am blessing you; you are blessing me; I am blessing God; God is blessing us.

In English the word blessing is a gerund, an ongoing-action word. I am blessing you; you are blessing me; I am blessing God; God is blessing us.

In Hebrew, ברכה / brakha is related to breikha (fountain) and berekh (knee). We bend ourselves in acknowledgement the fountain from Whom all blessings flow. (Those insights come from R' Marcia Prager in her book The Path of Blessing, which I reviewed back in 2004.)

The seder meal is full of blessings. We bless candles, bless wine, bless the greens we dip in salt water, bless matzah, bless hand-washing, bless our meal, bless the Holy Blessed One Who brought us out of Mitzrayim with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm.

And then there are the blessings of our togetherness, of sitting around a table with loved ones, of entering into familiar stories and songs and poems and psalms, of retelling once again the story that makes us who we are. Experiencing seder is itself a blessing.

Several years ago I took a class at the old Elat Chayyim, taught by Rabbi Barry Barkan, on the practice of offering blessings. We studied a variety of texts relating to blessings. Barry also challenged us to give spontaneous / impromptu blessings to people over the course of the week. The first few times I turned to someone in the class and said, "May I give you a blessing?" I felt a little bit awkward, as though I were play-acting. But what I took away from that class is that each of us can be a conduit for the blessings that God pours into creation.

"Blessing is a state of being; it may not change the situation, but it changes our response to the situation," teaches Reb Barry. (Here's a transcript of one of his teachings on blessing, given over at the Aquarian Minyan in 2008.)

In Jewish tradition we don't simply speak blessings; our language speaks of making blessings . We can give blessings, or perhaps more accurately channel them (as R' Barry teaches), and we can make blessings (as when we bless the elements of the seder meal, blessing God Who creates all things.) And, as songwriter Debbie Friedman noted, drawing on Torah (may her memory be a blessing), we can make ourselves a blessing. Each of us can be a blessing in the world.

That's part of the gift of the Exodus. Once we were slaves, unable to bless, unable to access blessing in our own lives or to articulate it for others. The spiritual constriction of slavery precludes blessing. But now we understand ourselves to be freed from that constriction. We are free to enter into relationship with the Holy Blessed One -- to sanctify every moment of our lives -- and to channel divine blessing for those we meet.

This post is part of #blogExodus. Follow other posts on the path to Pesach via the #blogExodus and #Exodusgram hashtags!

March 17, 2013

A sweet scent: d'var Torah for Vayikra

Here's the d'var Torah I offered yesterday at my shul. (Crossposted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

This week as we begin the book of Vayikra, Leviticus, we enter into a mystical world of flour and oil, incense and entrails. We call these things sacrifices, though that English word misses the mark of what I think the Hebrew really means. The Hebrew word is קרבנות, which comes from the root which means to draw near. The korbanot are offerings intended to draw us near to God.

Again and again in this week's Torah portion we read that we are to make a ריח ניחח, a pleasing scent, to Adonai. I hear those words and I think of woodsmoke, fine incense, the mouthwatering aroma of good barbecue. Once upon a time we understood our korbanot as our way of putting something fragrant into the air for our invisible Deity to consume.

I like to think of the reiach nichoach created by our choices. Think about how we behave in the world, how we treat one another, whether or not we take the time for the spiritual practice of mitzvot.

Do our actions create a reiach nichoach, a sweet scent, for Adonai?

One of the offerings described in this parsha is an offering of unleavened wafers spread with fine oil -- what we might think of as fresh hot matzah with really good butter. Can we make our observance of Pesach, coming up in just a few short days, a korban, something which will draw us nearer to the Holy Blessed One? Can we set the intention of eating matzah that week with gratitude that we have this practice for remembering our story and celebrating our freedom?

Can we make choices which will create a spiritual fragrance to waft up to God on high?

I'll close with a Torah poem for this week's portion, which you can find in 70 faces, my collection of Torah poems, published by Phoenicia Publishing, 2011.

KORBAN

You'll need a smoker.

Get one from Home Depot

and tighten each screw and bolt

exactly as the directions teach.

Split birch logs, and maple

kindle knobs of charcoal

fan them with cardboard

layer the hardwoods to burn.

Place the bird with reverence

then close the lid. What rises

will perfume the neighborhood,

your clothes, your hair.

Two hours later it's blackened,

crisp and burnished, but

inside: so tender even

a butter knife cuts through...

What constitutes a drawing-near

two thousand years or so

after the last sacrifice, bull

or pigeon, went up in smoke?

It's not the roasting that matters,

that's just barbecue -- though

maybe it's a reminder

on some level too deep to name --

but anticipation, and gratitude.

So that what burns bright

on the altars of our hearts

sends a pleasing odor to Adonai.

6 Nisan: Cleaning

In my earliest seder memories, we went each year to Dallas to celebrate Pesach at my Aunt Sylvia and Uncle Bill's house. Usually we flew on Southwest; it took about an hour to get from San Antonio to Love Field. But somewhere in my childhood, we started alternating years: one year in Dallas, one year at our house in San Antonio.

On the years when we hosted the seder at our house, the preparation for Pesach always involved taking down the boxes of pesachdik -- kosher for Passover -- dishes from the storeroom. I didn't grow up in a kosher home; we didn't maintain separate sets of dishes for milk and meat. But we did have a separate set of dishes for Passover which were strictly kept in accordance with halakhic constraints.

We had special Pesach dishes because some of our family members kept to those standards of kashrut. In the interest of inclusivity, my mother kept a separate set of dishes for Pesach only, so that our family who kept that kind of kosher could join us for seder. I don't think I realized any of this at the time. The fact that we had special dishes we only used during these few days each year just added to the holiday's specialness.

So every other year, when it was our turn to host, my mom and her army of helpers would kasher the kitchen, scrubbing and scouring and covering surfaces with tinfoil, and bring down the pesachdik dishes from the high shelves where they lived the rest of the year. And once the kitchen was kashered, my grandfather Eppie, of blessed memory, would make the matzah balls. (One year I took lessons from him; I still use his method now.)

My own preparations for Pesach tend more toward the spiritual (reading Hasidic texts and poring over my haggadah) than the practical. But when I clean my house at this season, I think of generations of my ancestors who searched every cranny for hidden crumbs of hametz, and I'm grateful for the work they did to keep Pesach meaningful and alive.

This post is part of #blogExodus. Follow other posts on the path to Pesach via the #blogExodus and #Exodusgram hashtags!

March 16, 2013

5 Nisan: Matzah

ODE TO MATZAH

Hello matzah, my old friend:

You've come to dry my mouth again... -- Hazzan Jack Kessler

Evocative as

Proust's madeleines.

Every seder I've ever known

is encapsulated in your ridges.

I love the uneven rounds

the baker makes:

that thinnest flatbread,

a savory buñuelo.

But the version of you

that I know best

is square as a pizza box,

crenellated like cardboard.

You're the hardtack of slavery

and the waybread of freedom.

Liberation, dry and dusty

as a hamsin wind.

Sprinkled with salt

slathered with horseradish

scrambled with eggs and pepper

the taste of being Jewish in spring.

This post is part of #blogExodus. Follow other posts on the path to Pesach via the #blogExodus and #Exodusgram hashtags!

March 15, 2013

4 Nisan: Chametz

Two of the central mitzvot of Pesach have to do with eating. Specifically, with bread, that foodstuff which, conventional wisdom has it, is the very staff of life. One mitzvah is to eat matzah, unleavened bread, in remembrance of the waybread we baked in haste for our journey out of Mitzrayim. Another mitzvah is to eschew chametz, leavened bread, during the week of Pesach.

Over time, our interpretations of these mitzvot have become elaborate and detailed. There are many places you can turn to find explanations of what, exactly, constitutes hametz in the traditional rabbinic understanding, and of how you would go about removing the hametz from your home according to traditional practice.

But every year, it seems, I hear from someone for whom these practices bring not spiritual satisfaction but anxiety and constriction. Maybe you already struggle with issues of control and consumption. Maybe you feel buried by the details and fear that you can't possibly live up to these ideals. Maybe the notion of inspecting food labels for a trace of a product made out of a leaven-able grain feels unhealthily compulsive to you.

I don't believe that Pesach is an all-or-nothing game. There's room for gradations of practice. For God's sake (and I mean that quite literally!) don't fall into the trap of figuring that if you can't observe the leaven-related mitzvot in a perfect and completely traditional way, you can't observe them at all.

The first mitzvah, that of eating matzah at seder, is a simple one and easy to fulfil. So nu, buy a box of matzah. Or bake your own. (If you're gluten-intolerant, there exist a variety of gluten-free matzot. Some would argue that gluten-free matzah isn't kosher for a seder, though I'm not in that camp; for me, what matters is that one eat matzah mindfully at seder. I would rather see you have a meaningful experience of the mitzvah than skip it because doing it would make you sick. But if you're going to be machmir about it, there's spelt matzah, which I'm reliably informed really is the bread of affliction.)

The first mitzvah, that of eating matzah at seder, is a simple one and easy to fulfil. So nu, buy a box of matzah. Or bake your own. (If you're gluten-intolerant, there exist a variety of gluten-free matzot. Some would argue that gluten-free matzah isn't kosher for a seder, though I'm not in that camp; for me, what matters is that one eat matzah mindfully at seder. I would rather see you have a meaningful experience of the mitzvah than skip it because doing it would make you sick. But if you're going to be machmir about it, there's spelt matzah, which I'm reliably informed really is the bread of affliction.)

And as for eschewing hametz, try this on: just give up bread for the week. Give up leavened bread. No bread, no yeasted sweet rolls, no bagels. Just that. And every time you think, "hm, I should have a piece of toast for breakfast," or "I'd like a sandwich on a hard roll" or "I want baguette with this soup," you'll catch yourself, and remember that it's Pesach, and remember that this week we eat in a different and more mindful way.

This is markedly less stringent than the traditional practice of ridding one's home of, and avoiding, all foods made with leaven-able grains. (And I'm not even getting into the question of whether or how you kasher your kitchen or sell your hametz.) But it serves the purpose, it does the spiritual work, which I believe the thicket of traditional practices intends to do. When we take on mitzvot, we open ourselves to the possibility of spiritual transformation. What might be transformed in you if you went the week of Pesach without eating leaven? You won't know until you try it.

In one Hasidic interpretation, hametz represents ego: that which puffs us up. Ego is an important ingredient in the human psyche; in order to be healthy, one needs ego! But an overabundance of ego can be unhealthy. So we devise spiritual practices to help us keep ego in check. During this one week of the year, we give up leavened bread, and in so doing, we remind ourselves to relinquish the puffery of ego, of overexalted self-importance.

During this one week of the year, we eat matzah instead of leavened breadstuffs. We remember the Exodus from Egypt; we remember that in every generation, we see ourselves as though we had personally experienced that liberation. We eat the humble waybread of the traveler, reminding us that sometimes we need to leap toward a new future even if that means baking flatbread in haste so we can (physically and spiritually) get moving.

It's pretty cool that we can compress all of that spiritual teaching into simply going a week without eating leavened bread.

This post is part of #blogExodus. Follow other posts on the path to Pesach via the #blogExodus and #Exodusgram hashtags!

You might also dig this one from the VR archives: Passover, matzah, dialectics, 2006.

March 14, 2013

3 Nisan: Slavery

T'ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights notes that "t]o be a Jew is to know both slavery and liberation" and that "[b]ecause of the Jewish experience of the Exodus, the Torah commands us to protect the stranger in our midst 36 times — according to the Talmud, more often than the laws of the Sabbath or of keeping kosher." T'ruah continues:

And yet, 3000 years after the Jewish people are said to have been liberated from slavery, and 150 years after the Civil War, more people are enslaved today than at any other point in history. According to the most conservative estimates of the International Labor Organization, nearly 21 million people are held in situations of forced labor today: 3 out of every 1,000 people in the world.

(That's from T'ruah's index page on slavery and human trafficking.)

It's easy to imagine that the story of our Exodus from slavery is ancient history. (Or perhaps that it's not history at all -- for some of us it's a kind of deep literary or spiritual story which doesn't need to be rooted in verifiable historical experience.) It's easy to think about the Pesach story as a metaphor for our relatively comfortable lives: to what -- our jobs, our expectations -- do we enslave ourselves? And how can we know ourselves to be liberated from those places of constriction? Those are great questions. I ask them every year at my seders, and every year the conversations which ensue are meaningful.

But slavery is still real. Slavery happens today. There are people enslaved in actual debt bondage around the world -- and human trafficking, which is a pernicious form of slavery, still happens. (See Slavery, trafficking, and people of faith, 2008.) That's the most extreme example -- but there are also people who work in unthinkably poor conditions for unthinkably small amounts of money, and that's a kind of slavery too. (Are the tomatoes you buy at the grocery store slavery-free?) There are people for whom credit card debts mount so high that they feel as constricting as slavery. (See Credit Card Debt Explained With a Glass of Water.)

When you sit down for your beautiful Pesach meal, be conscious that slavery wasn't just what (might have) happened to the Israelites in ancient Egypt. It isn't just a shameful American legacy. It's something that still happens, in a variety of ways. Our people's central story holds that we were slaves to a Pharaoh in

Egypt but our God brought us out of there with a mighty hand and an

outstretched arm. It's our job to be the mighty hands and

outstretched arms which will free those who are enslaved today.

This post is part of #blogExodus / #Exodusgram. Follow other posts on the path to Pesach via those hashtags!

March 12, 2013

Need a haggadah?

So hey, maybe you've noticed that Pesach is coming soon. (Really soon. March 25!) If you're in need of a haggadah, you're in luck: here are two versions of the Velveteen Rabbi's Haggadah for Pesach, both available as a free download.

Velveteen Rabbi's Haggadah for Pesach, Version 7.2: 48 pages (2012)

Velveteen Rabbi's Haggadah for Pesach, Version 7.1: 82 pages (2011)

(Those links go to the blog posts detailing what's new in each of those editions; the blog posts also have download links. And you can always find the most recent editions at the ceremony archive page of my website.)

If you use the haggadah, please drop me an email or leave a comment and let me know; I'm always interested in hearing about people's experiences with the haggadah (and in finding out where else it's being used!)

Happy new month of Nisan!

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers