Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 195

March 28, 2013

On children, and suffering, and this day of the Omer

Whatever gets in the way of the work, is the work. So taught the poet Jason Shinder, may his memory be a blessing, and that sentence has become one of my mantras. It works for me on both a poetic level (whatever is obscuring the poem I think I need to write, that very thing is probably what I really ought to be writing about) and a spiritual one (whatever life "stuff" is getting in the way of my spiritual practice needs to itself become the spiritual practice.) The work -- of creativity, of spiritual life, of living -- is made of whatever I experience in the moment, not whatever I imagine I ought to be experiencing, or whatever I had planned to experience.

Lately what's getting in the way of (at least some of) the work is latent anxiety about the certainty that our son will experience pain. This has arisen for me because we've had a few medical adventures recently, and as a result I've been newly-confronted with reminders that just as everyone who lives in a body sometimes experiences pain, so will our little boy. Intellectually I can tell you that nothing he's experiencing is a big deal. (Really, really not a big deal.) But emotionally, the prospect of our son suffering stops me in my tracks. I would do anything to forestall or prevent that, if I could. As would any (healthy) parent; the sentiment is so obvious that it's banal. Of course I wish I could protect him from pain. And I can't.

I know that his minor bumps and bruises and routine procedures are vanishingly insignificant, and that not all children are so fortunate. Take those two little boys who are sick, about whom I wrote back in the fall -- a six-year-old with leukemia; a four-year-old with a brain tumor -- just to name two examples from within my online circle of friends. (Sam appears, thankfully, to be doing great. Gus is finishing chemo; please read his mom's latest update, which talks about their journey and the other kids they've met along the way.) There are so many sick kids in the world. I ministered to a few of them when I was a student chaplain. I know that I would have a much harder time with that part of hospital chaplaincy now that I'm someone's mom. I know in my head that children suffer, but I can't bear to know it in my heart. Or: I know it in brief flickers, and then I put at least a partial lid on that knowing, because I can't inhabit that knowledge and also function in the world. My heart feels too tender.

Several of my friends have been reading and discussing Sonali Deraniyagala's book Wave (see, e.g., Lorianne DiSabato's post after Wave at Hoarded Ordinaries, or Teju Cole's review A Better Quality of Agony in the New Yorker.) Deraniyagala lost her entire family in a tsunami: husband, children, parents, everyone she loved. Wave is her memoir and her remembrance of them and of what she lost. I believe that the book is powerful and well-written and important, bit I don't know if I can bear to read it. There, too, I'm operating out of heart rather than head. I'm inhabiting the realm of yetzirah, emotions, rather than briyah, intellect. Intellectually I believe that Deraniyagala's book is tremendous. Emotionally, I don't think I can face it. At least not right now.

"Making the decision to have a child is momentous. It is to decide forever to have your heart go walking around outside your body." I've seen that quote floating around in various forms for years. (It's attributed to Elizabeth Stone, author of A Boy I Once Knew.) Granted, it's a cliché to say that I didn't wholly understand it until I had a child, but I suppose there's a reason why some clichés endure. Yes: some part of my heart is walking around in the world, learning and trying and striving and falling and laughing and wailing and doing all of the things that children do. A part of my heart is out there, independent, living on his own. And I can't spare him suffering, even though I wish I could. It's a kind of emotional and spiritual exposure, as though some part of my own heart and spirit which had been safely tucked-away were now open to the world, to the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, to the physical suffering which every body comes to know.

In the Counting of the Omer, today is the day of tiferet she'b'chesed, harmony and balance within lovingkindness. The quality of chesed, of overflowing love, is one that (the kabbalists teach) we and God share. "Parent" is one of our foremost metaphors for God. God is the Parent Who births all of creation, who feels our joys and our sorrows, who suffers when we suffer. And God also manifests through the quality of tiferet, harmony and balance. Today is the day when, as the kaleidoscope of the Omer turns, the two qualities reflect and refract one another. The day of balance within the week of lovingkindness. Lovingkindness filtered and framed through the kind of harmoniousness which arises when everything is in balance.

Maybe my work today is to (re)learn how to imbue chesed with today's quality of tiferet, to temper my overflowing openheartedness with the harmony which arises when good love has good boundaries and balance is reached. Suffering is real, and children experience suffering, and I wouldn't want to be the kind of person who doesn't feel tenderhearted dismay at remembering that reality anew. But today is a day for finding balance within that space of tender heart. Maybe I can find it through celebrating the caregivers, parents and grandparents and nurses and doctors and friends, whose loving hands manifest the presence of God in caring for all of the children in need.

March 27, 2013

Today is the First Day of the Omer!

Today is the first day of the Omer -- the 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot, between liberation and revelation!

Today is the first day of the Omer -- the 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot, between liberation and revelation!

I'm not going to manage daily Omer posts this year (as I did last year on my congregational blog), but here's my post for Day 1 of the Omer last year -- just ignore the Gregorian date, since the first day of the Omer this year began at sundown on Monday March 25, which is to say, last night.

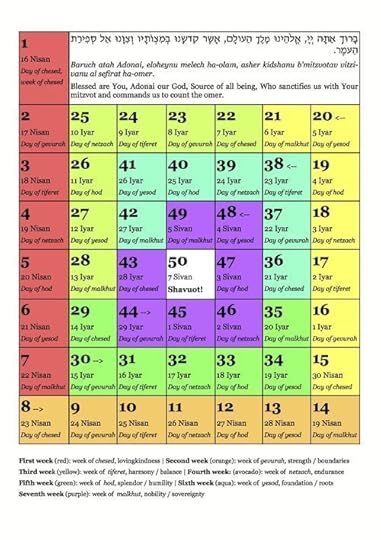

The kabbalists of Jewish tradition developed the idea that these seven weeks are a special time for focusing on a set of seven sefirot, seven divine qualities which we share with God: lovingkindness, boundaried strength, harmony and balance, endurance, humility, roots / foundation, and nobility / sovereignty.

I like to think of these qualities as facets of a gem, and during each week of the Omer, a different facet is held up to the light. Or perhaps, lenses / facets of a prism. Shine white light through a prism, and the seven colors of the rainbow emerge. Shine divinity through the prism of these seven weeks, and these seven qualities come into new focus.

And because there are seven days in each week, we rotate through the seven qualities each week, too.

Today is the day of chesed she'b'chesed, lovingkindness within lovingkindness. Abiding love, abounding love, lovingkindness and compassion which overflows our hearts and spills into the world around us. May we embody this quality as we move through the world today, on this first step toward the wonder of the revelation at Sinai.

If you're looking for Omer-counting resources, here are four wonderful books for counting the Omer: one by Shifrah Tobacman, one by Rabbi Min Kantrowitz, one by Rabbi Jill Hammer, and one by Rabbi Yael Levy. Rabbi Levy is at Mishkan Shalom, and each year she sends out daily Omer teachings via email and Facebook -- you can learn more, and sign up, here: Count the Omer with Us from Passover to Shavuot. And the spiraling map of the Omer count which illustrates this post was adapted from the one I found here: Counting of the Omer | Temple B'nai Abraham -- but I added the color-coding and the indications of which qualities are ascendant on each day. Here's a printable pdf if you want it:

ColorfulOmerChart

[pdf]

March 26, 2013

Meeting our children where they are

On Pesach, the child asks the parent: "Why is this night different from all other nights?" The Hasidic master Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev sees in this a deep teaching about how to parent and how to be like God.

He begins this teaching in a slightly odd place: by wondering aloud why we have the tradition of ritually asking this question at Pesach and not, for instance, at Sukkot, when we're dwelling in little huts with permeable roofs. He notes that there's a teaching (in the Gemara) that some people say the world was created in Tishri, and others say it was created in Nisan. Some say the new year is in the fall, and others say the new year is in the spring.

Ultimately, his answer to this question ("is the new year in the fall or in the spring?") is "yes." Which is to say: they're both meaningful, though in different ways. In Tishri (the Days of Awe), we celebrate the creation of the universe which happened, he says, through chesed, divine lovingkindness. This is the birthday of creation, the new year for all beings and all things. Creation arose because of God's overflowing compassion and lovingkindness, and that lovingkindness extends to everything.

In Nisan (during Pesach), we celebrate the miracles and wonders which God performed in liberating us from slavery. Both of these are important beginnings: the creation of the world, and the creation of our people as a people. (Indeed -- we mention both in the kiddush, the blessing over wine, every Shabbat.) But they're different in tone. The Tishri new year is a universal new year, a moment of celebration for all existence. The Nisan new year is a particularistic new year, commemorating our community's origins.

And the question "why is this night different from all other nights" isn't asked at that other end of the year, at the universalistic new year of all creation. We ask it at Pesach, our festival of liberation. Here's R' Levi Yitzchak:

The Holy Blessed One constricts God's-self for the sake of God's people Israel, and takes great pleasure in this, and in this God's will is fulfilled. An example of this is the question of the son to the father ["Why is this night different" etc]. For the wisdom of the father is greater than that of the son, and only through his love for his son does the father constrict himself in order to offer a response to the son's question. And this is the example, as is known: the Holy Blessed One constricts God's self in the qualities of Israel and takes pride in them and their doing of God's will.

Or -- phrased in a more contemporary idiom --

On Pesach, it's the child's job to ask, "Why is this night different?" And it's the parent's job to constrict her/himself, and to channel love and knowledge into an answer which the child can process -- and also to take joy and pride in the child's growth and desire to know.

God's wisdom is greater than ours, as a parent's wisdom is greater than their child's. In love, God contracts himself/herself in order to make room for us and to answer us where we are. Just so, we too can pull back in order to make space for our children, and to answer their questions in a way which will reach them where they are. When we pull back to make space for our children to grow, we follow in God's footsteps.

Kedushat Levi teaches us that God takes great pleasure in this tzimtzum, this process of self-constriction which makes space for us in the world. And God takes pleasure in us and in our questioning and in our growth. Like a loving parent, God holds back some of God's greatness in order to make room for us and to respond in a way that we can hear. And like God, it's our job as parents to gauge where our children are at, and to relate to them where they authentically are.

(You can find this teaching in ספר קדשת–לוי השלם; it's the second teaching in his דרוש לפשח / "Pesach teachings" section.)

First night of Pesach: I don't want to forget

The experience of reading my poem "Order" at the start of the seder, and managing for once not to break into tears at reaching the mention of my grandfather, of blessed memory, who taught me how to make matzah balls.

My son excitedly explaining to his friend that they were going to look

for the hidden matzah and then get presents! And then the three kids

running around the house looking for the afikoman. Hearing them talking

to each other about how they had to just -- keep -- looking.

Reading R' Lynn Gottlieb's poem about removing the hametz in the month

of Nisan, which I've read at my seders for probably 15 years now. Going

around the table, stanza by stanza, the familiar words connecting this

year with all the years before.

My son singing the "a-a-men" at the end of each borei pri hagafen

blessing, after each of the four traditional cups of wine. No matter

where he was when we blessed the wine -- whether at the table, or

playing in the living room -- he piped up and sang the amen for us, with obvious pride.

Beginning the Maggid / Storytelling section of our seder with the "story about stories" -- which ends with "'All I can do is tell the story, and this must be sufficient.' And it was sufficient." Ethan reading the Martín Espada poem during Motzi/Matzah. My mother-in-law reading the Gerard Manley Hopkins poem during Hallel.

I knew that a few thousand miles away, my extended clan was together at my brother's house, singing all of the prayers which were part of my childhood seder soundtrack. I love those old melodies and those old words, and I'm sorry I didn't get to sing them with my parents and my siblings and my cousins.

But I also love the poems and readings and songs which have become part of our own idiosyncratic household tradition. And I'm so grateful to be able to celebrate Pesach, this year and every year, with family and beloved friends.

Chag sameach to all! I hope your Passover is sweet.

March 25, 2013

14 Nisan: Being

I always get caught up in the details of Pesach. The recipes, the matzah balls, the groceries, the cooking, the haggadah, the psalms, the songs. I always want to create a perfectly meaningful seder: for myself, for my family, for my guests. I love this holiday so fiercely that I want to share that love with everyone. I want everyone to come away from the table feeling nourished in all four worlds of body, heart, mind, and soul. I want to experience the spiritual peak of being magically swept up to the top of the mountain with God at Pesach -- so that as I begin the long climb back up to the spiritual heights of Shavuot, I'm inspired and enlivened by knowing just what joys await me once I get there again.

I always get caught up in the details of Pesach. The recipes, the matzah balls, the groceries, the cooking, the haggadah, the psalms, the songs. I always want to create a perfectly meaningful seder: for myself, for my family, for my guests. I love this holiday so fiercely that I want to share that love with everyone. I want everyone to come away from the table feeling nourished in all four worlds of body, heart, mind, and soul. I want to experience the spiritual peak of being magically swept up to the top of the mountain with God at Pesach -- so that as I begin the long climb back up to the spiritual heights of Shavuot, I'm inspired and enlivened by knowing just what joys await me once I get there again.

In my haggadah there is a poem by Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb, who is now a friend and colleague but who was known to me only by reputation when I first discovered her work many years ago. That poem speaks of the process of bedikat chametz, removing the leaven from our homes on the eve of Pesach. (Here's a short ritual for bedikat chametz, which also includes that poem: BedikatChametz.pdf) After we read that poem, at my seder, we sometimes go around the table and share an emotional or internal hametz which we want to relinquish as Pesach begins. Often, what I need to relinquish is my fantasy of the perfect seder -- my fantasy that I can create an experience which will sweep everyone up into ecstasy, which will wholly connect all who are present with our ancestors and our community and our God.

This yearning for seder perfection, bumping up against the inevitable realities of the world's natural imperfection, is something I've wrestled with for years. And it is, if anything, even more true now that we are parents. I want to create the perfect seder -- and I know the odds are good that at some point during the evening, our three-year-old will have an entirely age-appropriate tantrum because his usual routines are disrupted, or because we won't let him watch cartoons during the seder, or because he's overstimulated and up too late. I want to create the perfect seder -- and I know that there is no such thing; that the childhood seders I've enshrined in memory weren't perfect; that even if I could fill my table with scholars and sages who love the tradition even more than I do, the seder wouldn't achieve perfection.

Far better to learn to find the perfection in what is, instead of wishing for a kind of perfection we can never attain. The seder isn't just about doing, although there are certainly a lot of things to do in order for the evening to be complete. (The fifteen steps from kadesh to nirtzah, the songs and prayers and psalms, the food rituals of hardboiled egg and matzah ball soup...) The seder is also about being. It's a chance to experience being free. To be in the moment, to be with friends and family, to be blessed by the light of the full moon of Nisan in 5773 which will never shine again after this night. It's a chance to be joyful even when the glass breaks, or the kugel burns, or the children don't pay attention. After all the flurry of work and preparations -- cleaning, cooking, studying, readying -- it's a chance to just be.

Chag Pesach sameach to one and all. May this holiday be whatever you need it to be.

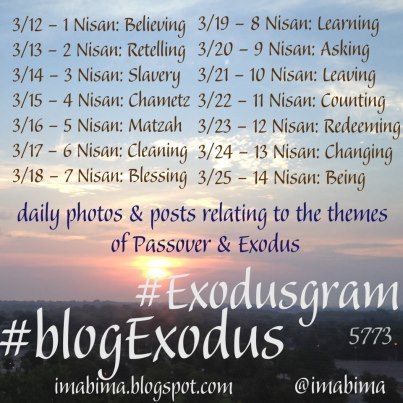

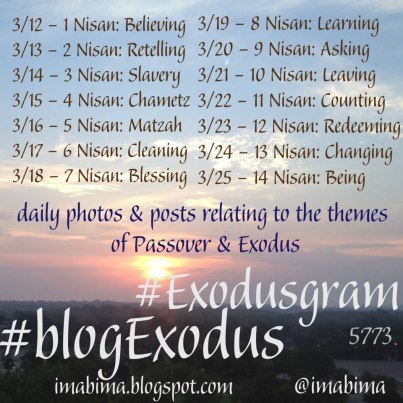

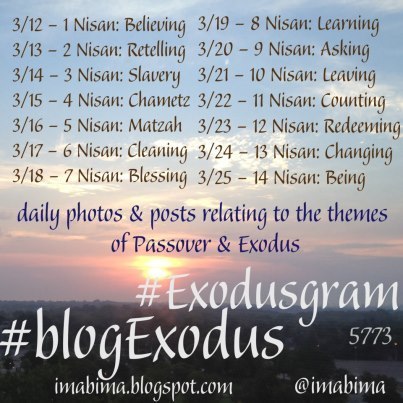

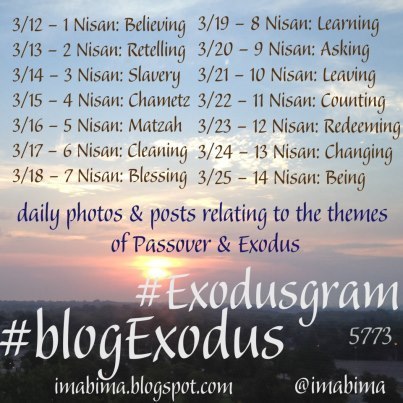

This post is part of #blogExodus. Follow other posts on the path to Pesach via the #blogExodus and #Exodusgram hashtags!

March 24, 2013

13 Nisan: Changing

This is a story about change.

Look: the seas are parting.

It's happening now. Open your eyes.

We were slaves to a Pharaoh in Egypt

but God brought us out of there.

This is a story about change.

The womb which had kept us alive

became constricting.

It's happening now. Open your eyes.

It's time to forget our anxieties

and leap off the precipice.

This is a story about change.

Even God is all about change --

I Am Becoming Who I Am Becoming.

It's happening now. Open your eyes.

The moon is almost full

to light our wanderings.

This is a story about change.

It's happening now. Open your eyes.

This is not-quite-a-villanelle. (A traditional villanelle rhymes, whereas this does not.) It's inspired by villanelles, anyway, and by their use of repeated lines.

Every year we read the same seder story, and every year we experience it differently -- not because it has changed, but because we have. (The same is true of Torah which we read week by week.) In this poem, the same lines appear, but hopefully mean something slightly different each time they recur.

This post is part of #blogExodus. Follow other posts on the path to Pesach via the #blogExodus and #Exodusgram hashtags!

March 23, 2013

12 Nisan: Redeeming

In our daily liturgy, in one of the blessings surrounding the Shema, we praise God Who redeems us from Egypt, Who makes our transformation possible. That redemption from Egypt is a (arguably the) major theme of the Pesach seder.

In our daily liturgy, in one of the blessings surrounding the Shema, we praise God Who redeems us from Egypt, Who makes our transformation possible. That redemption from Egypt is a (arguably the) major theme of the Pesach seder.

For many of us, redemption is a difficult concept to wrap our heads around. We know what it means to redeem a coupon. But what do we mean when we say that God redeems us?

The Pesach story tells us that we were slaves to a Pharaoh in Egypt and that God redeemed us from slavery. That's one kind of redemption: being rescued from dire straits, from the constriction of Mitzrayim.

The name Mitzrayim stems from the root צר, which means constricted or narrow. Slavery is a form of physical and spiritual constriction. God busted us out of there, bringing us to the sometimes-terrifying wide-open-spaces of freedom, the open spaces of wilderness in which we could actively choose to enter into relationship with something greater than ourselves.

And, of course, the Pesach seder is filled with invocations of a future redemption, the redemption which will mark our entry into the messianic age when the work of perfecting creation is complete. Or the redemption which will arise when Moshiach, the messiah, walks among us bringing transformation. (Depends on how you understand "messiah," among other things. I wrote a somewhat clumsy discursus on that in 2004; really, for a better sense of my understanding of messianic time, read my 2011 poem On that day.)

The symbol of that future redemption is Elijah's Cup, the cup of juice or wine on every seder table from which, tradition says, Elijah invisibly sips at every seder in the world. Elijah is the harbinger of messianic redemption, the prophet who announces the coming of a world transformed and healed.

The seder meal bridges the redemption that happened back then, at the moment of the Exodus, and the redemption which awaits us in days to come. When we call God our Redeemer, we are affirming that God is that force which lifts us out of difficult circumstances, which helps us to become better than we were before, with Whom we partner in trying to heal the broken world.

Each of us is commanded to experience the story of the Exodus as though it had happened to us, ourselves, not to some ancient and possibly imaginary ancestors eons ago. God lifts us out of slavery and constriction every day, if we are willing and able to reach out of ourselves and yearn for more. Redemption isn't just in our distant past and in the unimaginable future. Redemption can be now.

For more on this: try Kolel's Reb on the Web article Redemption.

This post is part of #blogExodus. Follow other posts on the path to Pesach via the #blogExodus and #Exodusgram hashtags!

March 22, 2013

11 Nisan: Counting

Counting the days. Pesach is coming soon, sooner, sooner.

Counting the days. Pesach is coming soon, sooner, sooner.Counting how many people are coming to seder. How many on first night? How many on second night? Do we have enough silverware, enough wineglasses?

Counting ingredients. How many eggs do I need for the matzah balls? How many to hardboil? How many for the potato kugel? I wrote in a poem years ago that "no matter how many you buy / there are never quite enough eggs at Pesach," and every year it turns out to be true.

How many napkin rings do I have? (Not enough. Time to order a dozen, quickly.) How many vinyl Pesach placemats do I have, to protect the tablecloth where the three-year-olds will be? (Better buy three, to be on the safe side.)

Counting haggadot. Of those, this year, I have enough already. Spiral-bound, fronted with brilliant orange paper and a clear plastic cover. Some of the pages are lightly stained with wine or horseradish from last year or the year before. The sign of a haggadah well-used, well-loved.

This year, two seder plates: the beautiful ceramic one my mother's sister gave us as a wedding gift, and a plastic one from Target so there's one that the kids can explore without fear. This year, ten felt plague puppets in a glass basket which used to belong to my father's mother and which came to me as a gift from my "other mother" years ago. The first Rachel Barenblat had given it to her, and she passed it on to me.

And in the flurry of all of these preparations, I know that as soon as we reach the second night of Pesach, we begin a new kind of counting. The Counting of the Omer, measuring the 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot, between liberation and redemption. I'm so caught-up in seder preparations, both physical and spiritual, that it's hard to believe that seder will launch us into seven weeks of intensive spiritual work, opportunities for all kinds of revelation. It's a bit like being pregnant, focusing energy on labor and delivery, but knowing that after birth there's a whole new journey ahead. New time to measure, new days and weeks to count.

For now, the clock ticks down until Monday evening, until the fifteen steps of the seder which we'll count one by one as landmarks on our journey. Time, now, to make our preparations count.

This post is part of #blogExodus. Follow other posts on the path to Pesach via the #blogExodus and #Exodusgram hashtags!

March 21, 2013

10 Nisan: Leaving

Why do we eat matzah? Because during the Exodus, our ancestors had no time to wait for dough to rise. So they improvised flat cakes without yeast, which could be baked and consumed in haste. The matzah reminds us that when the chance for liberation comes, we must seize it even if we do not feel ready—indeed, if we wait until we feel fully ready, we may never act at all.

That's in The Velveteen Rabbi's Haggadah for Pesach (version 7.1, 2011). The same sentiment appears in The VR Haggadah for Pesach (Abridged & Expanded) (version 7.2, 2012) in the poem "Ready" -- "But if you wait until you feel fully ready / you may never take the leap at all." (That's one of the three poems I shared during my smicha ceremony a few years ago.)

It's one of my favorite ideas in the seder and in the Exodus story. It's a deep spiritual truth. Sometimes we have to leap before we feel entirely ready to do so. Reaching freedom means stretching ourselves beyond our comfort zone. I always get a little shiver when we reach this line in the haggadah, because it feels so real and so true to me.

Rabbi Nachman of Bratzlav has a beautiful teaching on this theme (sometimes jointly attributed to his amanuensis, Reb Nosson.) I posted it here some years ago: On leaping, without delay. The gist is this: Mitzrayim, the Narrow Place, exists in every era and in every human experience. And each of us is called to take the leap of leaving Mitzrayim in our own lives.

When the Israelites left Egypt, they did so in haste, without waiting for their bread to rise. We too must take leaps into the unknown, and in the moment of so doing, we need to resist the impulse to slow ourselves down by worrying about what's coming next. Reb Nachman frames it in terms of: when you realize that you're mired in Mitzrayim, take the leap to free yourself without worrying about how you're going to support yourself in your new life.

I hadn't yet studied that text when I first wrote "if we wait until we feel fully ready, we may never act at all" -- but I think we're on the same wavelength there, Reb Nachman and I. Worrying about parnassah (in his framing) can be a way of waiting until one feels fully ready: until one has a complete plan in place, a new job and new apartment, a new situation all mapped-out. And believe me, I'm one of those people who likes to have a plan in place. Maybe that's why I find this teaching so valuable. My temperament inclines me to take my time and wait until I have things all-planned-out, but the Pesach story reminds me that sometimes I have to take the leap and trust that God will provide.

This post is part of #blogExodus. Follow other posts on the path to Pesach via the #blogExodus and #Exodusgram hashtags!

March 20, 2013

You Don't Have To Be Wrong for Me To Be Right: R' Brad Hirschfield on faith without fanaticism

We need to see that everyone who is not just like us is not some kind

of restoration project, just waiting for us to "fix" them and turn

them into poor imitations of ourselves. Do we really want a world of

people who look, think, and act just like we do? That's not spiritual

depth or religious growth, but simply narcisissm with lots of footnotes.

That's the kind of wisdom I've come to expect from Rabbi Brad Hirschfield.

That's the kind of wisdom I've come to expect from Rabbi Brad Hirschfield.

Rabbi Brad Hirschfield is one of the co-presidents of Clal, the National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership. Along with the other co-president, Rabbi Irwin Kula, he teaches at our Rabbis Without Borders fellows retreats. On my way home from our most recent retreat, I started reading his book You Don't Have To Be Wrong For Me To Be Right: Finding Faith Without Fanaticism.

I knew that R' Brad identifies as Orthodox, and I had a vague sense that his spiritual trajectory had been quite a journey. But I didn't realize quite how broad that journey was until I began reading this book. In the early chapters he describes his falling-in-love with Orthodoxy; his desire, as a senior in high school, to study for a year in Israel; and his immersion in the culture of the settlers of Hebron.

I visited Hebron back in 2008 (see A day in Bethlehem and Hebron), but I didn't go into the settlement, and I didn't meet anyone who lived in that part of the city. Early in this book, R' Brad offers a stark and unflinching description both of what drew him into the movement -- and what caused him to leave. This is the longest quote I'll offer, but I don't want to abridge it any further, because this is such a powerful recounting, and it's a voice I haven't seen in print elsewhere. R' Brad writes:

I was a pilgrim who had finally reached his destination. I felt whole.

Complete. This was what God wanted. This was what God had commanded:

Brad Hirschfield, nice Jewish boy from the North Shore, standing at

a tomb in Hebron, surrounded by one hundred thousand Palestinians who

hated my presence there, singing Hebrew prayers.

I know it may sound ridiculous now, but then I didn't question it for one moment. There was not an inkling of doubt.

[The settle underground] began advocating for an increasingly harsh response against violence directed at Jews....Most of this made sense to me. Jews were being killed for settling in what had once been Jewish homes.

This was our land, given to us by God.

For two years I gave myself over to Levinger and his group and the militant

arm of the settlers' movement. When settlers Menachem Livni, Shauli Nir,

and Uzi Shabaraf (whom I knew, although I was not in Hebron that day)

fired into the Hebron Islamic College and killed two Palestinian children,

I really felt sick...

Most of my group felt it was a tragic mistake, but they also thought it a natural

result of continuous violence against us...No one questioned the wisdom of

building the Hebron community in light of what had happened.

I found myself outside the fold. I stopped going to Hebron. I had no idea

how to discuss how I felt with anyone within the settlers'

movement. And I had no desire to talk to anyone outside about it, either...

I was no longer a pilgrim. I didn't quiet know what I was.

It's so easy for those of us outside of a particular fold to castigate those within, and vice versa. And that's true whether the fold is the settler movement, a religious denomination, a community, a subculture, a nation. This book opened up for me both some of what might draw a person into religious fanaticism -- and also the unique lessons such a person could bring with them upon, mercifully, exiting that world for one which is more expansive and pluralistic.

After 9/11, he writes, he realized that he needed to confront his own past, to begin writing and speaking about his experiences as an ardent young settler. "Religion had flown those planes into the Twin Towers, and I had practiced a form of that religion. It is the religion of pilgrims, of people who see no way but their own way, and treat people who do not support them as mistakes that need to be erased," writes R' Brad. Near as I can tell, he's dedicated his rabbinate to teaching that there is another way.

In one of my favorite one-liners of the book, R' Brad writes, "I have come to believe that religious traditions exist not to serve the faithful, but to help the faithful serve the world." As a rabbi and as a Jew, that could be one of my mission statements. And serving the world doesn't mean reshaping the entire world in one's own image. Later in the book, he notes:

Isaiah's prophetic vision of a perfect world rests on the

principle that "perfect" looks different to different people. Isaiah's

house of prayer is for all peoples -- plural, not singular.

It most emphatically does not require a flattening-out of all distinctions.

In other words: we don't all need to be the same. I don't need everyone in the world to be Jewish. I don't need every Jew to choose the form of Judaism I myself have chosen, even though I love and am enlivened by this version of my tradition! It gets back to the first lines I quoted in this post: wanting to make everyone else just like me is narcissism. Learning to interact with, to respect, and even to love people who are different from me (without trying, or even wanting, to change them to make us more alike) isn't always easy, but it's valuable spiritual work. He continues:

Why is that to make things, even spiritual things, more ours, we so often

have to make them less someone else's? Why does being right depend on everyone

else being wrong? Do other children need to be failures in order for ours

to be successful? Do other women need to be ugly in order for my wife

to be beautiful? In love and beauty we can make room for difference, or at least

we seem to know that we should, but we have a harder time applying this expansiveness

to tradition and truth.

Right. Everyone can agree that just because my son is beautiful, that doesn't make someone else's son less beautiful. Beauty and love are not zero-sum games. There's always room for one more beautiful song, one more beautiful child, one more beautiful sunset. It's much harder to wrap one's mind around the notion that tradition and truth are also forms of love and beauty -- that just because Judaism is beautiful and true, that doesn't mean Christianity or Islam or Buddhism aren't.

This is one of the teachings I most value in Jewish Renewal. Over the years I've heard Reb Zalman teach time and again that each religion is a necessary organ in the body of humanity, that we need each religious tradition to be what it uniquely is. If the heart tried to be the liver, or the liver tried to be the brain, the body would be in trouble! And -- if the heart stopped speaking to the liver, we'd be in trouble too. Each religion needs to be what it is, and each religion needs to be in community and conversation with its counterparts.

There's a powerful chapter about the rededication of a synagogue in Auschwitz. In that context, R' Brad writes:

We have within us a greater capacity for overcoming the pain of our pasts

than we realize. We can make the walls that divide us fall down, and we can come

together to create new realities that acknowledge history without being chained by it.

That's a valuable teaching not only in the context of Holocaust history, but also in the context of contemporary Israeli/Palestinian violence. We can acknowledge history without being chained by it. It isn't always easy, but we can.

I've been all over the spectrum on what kind of God it is that I think I'm praying

to, but I've found that in my life prayer has value in and of itself to the

person who prays. It's not so much about changing God's mind as it is about changing

our own mind, which in the end is the only thing we can control anyway.

This is a teaching I have often given over to my own congregants and students. Prayer has value in and of itself, in my life and my experience. I don't know if it changes external reality or effects theurgical transformation on high, but I know that the practice of Jewish prayer changes and transforms me.

Late in the book, R' Brad acknowledges that the kind of pluralism he espouses isn't going to be everyone's cup of tea.

In a sophisticated pluralistic community there will be some people who say

"I want no part of this; count me out." That's fine. In fact, those people play a very important role

as border guards who help ensure the integrity and security of the community. But all borders

have to have gates; otherwise they imprison those within as much as they keep

perceived danger away. Some people are better at guarding the gates, and others are better

at scouting the territory beyond them. We always need both kinds of people, and at

different times in our lives we need to draw on each of those approaches.

I've heard Reb Zalman speak about this idea, too. This is another place where he uses a metaphor of the human body, teaching that within the body of the Jewish community, some of us are well-suited to be the "skeleton" (rigid and unyielding, sticking to the center) while others are well-suited to be the "heart" (more attuned to emotional realities), and so on. In other words: we who are out here on the lefty fringe of what my sister calls "groovy Judaism" need to be in relationship with those who are rigid and stringent, and they need to be in relationship with us. The Jewish community writ large needs those of us on the margins, and those of us in the center, both, always. That's part of what I hear R' Brad saying in this passage, too.

The long and the short of it: this is a powerful and poignant book, well-written and tight, and there's a lot of rich material here. I know I'll be returning to this text in years to come. I'm really grateful that it's out there as part of our communal conversation.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers