Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 202

January 14, 2013

Impromptu music at OHALAH2013

After lunch on Monday I go up to my room to rest for a short while, but within half an hour I'm back downstairs, knowing that I don't have the focus for the plenary session on ethics but wanting to be at least in communal space, if not actively engaging. (Conferences like this one are always a challenge for those of us who naturally fall somewhere between introvert and extrovert. I want to soak up time with my hevre, but I don't want to wind up overstimulated and cranky.)

The obvious place to go, for low-key hanging out instead of the kind of brain-engagement required by another conference session, is the area of the lobby with the fireplaces and the couches. (I remember playing there with 13-month-old Drew two years ago.) And when I get there, I find a wonderful surprise: a group of friends singing by the fire. So I sit down at the edge of the hearth and soak up the warmth of the fire and the warmth of their music, sometimes humming or singing along.

While I'm there they sing niggunim, secular songs ("Me and Bobby McGee"), Yiddish songs ("Shnirele Perele") extemporaneously rendered in English, lines from liturgy set to new melodies. More instrumentalists join the group. By the time I regretfully walk away -- wanting to stay, but also wanting to catch one of the sessions in the next slot -- there are two guitarists, three ukelele players, and one rabbi playing a keyboard harmonica.

The music is delicious and juicy. Rabbi Jack has a sweet presence and a sweet voice and a lot of Jewish Renewal history to give over. Rabbi Mark's mouth-harmonica solos are soulful, and when he offers an impromptu spoken-word riff which involves channeling Bob Zimmerman and wondering aloud whether he's going to wind up in somebody's blog post, my intention to write this here is crystallized! This little interlude is an unanticipated gift.

On my way out of the room I run into Rabbi Jan, the conference

chair, and we agree that this is something we couldn't have planned for

-- it had to just happen. Fortunately in this crowd, all you really need to do is give us space -- a few couches to sit on, perhaps a fire to gather around -- and a few moments we can steal from an otherwise overscheduled day, and we'll want to join our voices together, not only in planned liturgical prayer but also just in song, which is a kind of prayer all its own.

Rabbi Rachel Adler: What is Tradition, and How Do We Learn From It?

We often talk about tradition as a source of learning, but what is a tradition? Where are its boundaries? Is tradition a book or a code? Is it static or fluid? Who gets to part of it? How do you talk your way in? Why would a learner want a tradition?

Rabbi Dr. Rachel Adler begins her morning keynote address by unpacking our conference theme, "Mikol melamdai hiskalti," from psalms 119, which we have been translating, "From all of my teachers I have learned." She notes that Robert Alter translates it, "I have understood more than all my teachers, for Your precepts became my theme." The JPS translates it "I have gained more insight than all my teachers, for Your decrees are my study." But the rabbis of the Talmud understand it to mean "From all my teachers I have acquired understanding."

She goes on to cite Ben Zoma in Avot ch. 4, who asks, who is wise? and answers, one who learns from all people; as it is said, mikol melamdai hiskalti. "No one cites the second half of the verse. I have a hunch that the rabbis would have understood it to mean 'because Your precepts are my conversation.' Not my study, or my meditation. For the rabbis, study is a social act, and only as a last resort a solitary one."

I love that: for the rabbis, study is a social act. Yes!

Rabbi Dr. Rachel Adler speaks to OHALAH.

Rabbi Dr. Rachel Adler speaks to OHALAH.

She goes on to cite Ta'anit 7a, where Rabbi Chanina addresses specifically the web of participants that constitutes Talmudic tradition. "'Much have I learned from my teachers, and from my colleagues/ study partners still more, and from my students, most of all.' In this statement, R' Chanina inverts the presupposed hierarchy of Talmudic study. From the students one learns most. This is the very opposite of the way we tend to think of traditions, yet it is upon students that traditions rely." And she goes on:

When we talk about a tradition, we are talking about the speech acts and the other acts of a web of transmitters. Teachers to students, students to their students -- as long as the tradition is in good order. If a tradition is in good order, according to the philosopher Alester MacIntyre, a tradition is not a set of books or codes or a body of ancient prescriptions. A tradition is a conversation. Even a bit of a fight! He says, "Traditions, when vital, embody continuities of conflict." He adds, "A living tradition, then, is a historically extended, socially embodied argument."

And an argument precisely in part about the goods that constitute the tradition! By goods we mean, e.g., what is the good life? (One of the questions around which Pirkei Avot is built.) Or: what is shalom, or tikkun olam? Even: what is kavvanah? What is law? And why should it be important to us?

Rabbi Adler unpacks what a living tradition is: "historically extended -- that is, it stretches over many generations. It's socially embodied -- there are real people living out the various positions that are taken. Think for a minute about the importance of makhloket, disagreement, as the engine that makes Talmudic discourse go." And she cites the story from Brakhot in which Rabban Gamaliel tries to suppress the minority opinions of R' Yehoshua ben Chanania, and there's a rebellion in the academy; they fire Rabban Gamaliel, and they only take him back when he's made peace with R' Yehoshua.

During the time that R' Gamaliel was not in charge, all sorts of good things start happening. More participants are invited into the academy. There's a new energy in the academy now that it's safe to disagree. When R' Gamaliel returns, he has to share power with R' Elazar, who headed the academy when R' Gamaliel was deposed. "This, it seems to me, is a story about a failed attempt to repress the arguments that keep traditions alive." She continues:

A tradition is fluid if it's alive. The conversation twists and turns, but all the participants share basic vocabulary and a sense of participating in shared narratives.

As MacIntyre says, I can only answer the question what am I to do if I can answer the prior question of what story or stories do I find myself a part. Commitments emerge out of stories and are re-fashioned in stories.

I do certain things because I see myself as the daughter of Avraham, Sarah, etc. I do other things because I view myself as the inheritor of conflicts voiced by Bruriah. I do yet other things because this is what Sadie Hellman would have expected of her granddaughter. I learned these larger narratives that include me, and hence make demands on me, in the conversational community that transmits and reshapes the tradition.

I am part of that community, and consequently I shape and am reshaped.

I'm putting that last line in boldface because I find it really powerful. Being in community means both shaping, and be shaped by, that community. It's a responsibility (to help shape) and it's an acceptance (of being shaped.)

Today, she acknowledges, "tradition is a problematic notion. First: people tend to see themselves as autonomous individuals rather than as members of communities. They resent obligations beyond the private sphere. And, as we learned last night, this is the Sodom mentality."

"Second, knowledge gained from past minds, even the minds of our own elders, is largely undervalued in this culture. People are constantly looking toward the future but cutting themselves off from the past." Those of us here in the OHALAH room, she acknowledges, have Reb Zalman "who embodies for you both the constancy & the fluidity possible in the tradition" -- but we recognize that this is a rarity.

"Third, people are discrediting their ancestral narratives, replacing Jewish memory with Jewish history. As Yerushalmi says in his book Zachor, these categories actually serve different purposes. Historography is objective and descriptive. Memory is passionately subjective and not descriptive but normative."

A bit later, Rabbi Adler articulates the notion that:

Memory molds us as members of specific communities. The Pesach seder, e.g., is a communal exercise in fostering Jewish memory. In the seder, we're made to internalize a searing communal identity. We take in the belief that all of us were slaves and all of us were liberated. We emerge from the seder with the norm that every time we see a stranger, outcast, exploited person, we should be feeling: I have to help, this could've been me.Memory is about belonging to something larger than ourselves. Moses says, in Deut 29, "I made this covenant not with you alone, but those with those who are standing here with us this day before Adonai our God, and with those who are not here this day." When we're part of a covenant, we're connected to the past and invested in the future.

This is difficult in our time, when trying to impart a covenantal identity is swimming against the tide.

I'm taking very seriously the radicality of your choices to align yourselves with a tradition, with Jewish tradition.

And then Rabbi Adler asks the question, "Is our tradition in good order, as MacIntyre would say?" She talks about the communal "arguments about the goods, virtues, values of Jewish tradition and how they are to be lived-out," and argues that "All those who care about how Jews constitute their Judaism have a place in the arguments of tradition." I find that so meaningful that I promptly tweet it in the OHALAH_clergy twitter stream:

She cites the "tumultuous argument about the Akhnai oven in Bava Metzia 59b" (a wonderful passage, rich and deep and full of implications -- read it in its simplest form here, or for a more detailed view, I love Greg Fishbone's illustrated version The Oven of Akhnai) and notes that since then, "it's been agreed that the adjudication of halakha, and hence the shaping of tradition that are its context, are matters for human beings to work out. Making a carob tree move 100 cubits, making a stream flow backwards, or making the walls of the beit midrash lean in are not acceptable proofs of a position! Even getting a bat kol [a celestial voice from heaven] to attest to his correctness is not convincing."

Once the Torah has been given, we rely upon our own resources, not miracles or charismatic messengers, to relieve the burden of interpretation and decisionmaking.

"One idea that the Akhnai oven reveals to us as faulty, that is still faulty in our own time, is the excessively exclusionary boundary-making for the tradition." She notes that that story ends with a series of stories about the consequences of R' Eliezer's hurt feelings. "God is attentive to hurt feelings. There is a lesson here about the treatment of those who hold minority opinions. When are we going to learn to live in a pluralistic tradition?"

As a case like Women of the Wall illustrates, there are still powerful attempts to be both exclusionary and violent in making or re-making the boundaries of the tradition. If the boundary is too stringent, there can be no argument, and the tradition begins to stultify. If boundary-making excludes, as inauthentic, most of the world's Jewish population, clearly something is very wrong.

(Emphasis mine.) Granted, a tradition needs some boundaries. Not everyone is an authentic participant. As Lionel Trilling once remarked, "Some people are so open-minded that their brains fall out." (That gets a big laugh in this room, probably unsurprisingly.)

The question of who gets to participate in a tradition, to be part of its cross-generational web, is still relevant to us today. And of course, that's a beautiful lead-in to a conversation about women in Judaism.

"The Coming of Lilith" by Judith Plaskow; scroll by Rabbinic Pastor Sandra Wortzel, part of her multifaceted artists' book about Jewish feminism, on display at the conference. (Here's an image of more of that book.)

Rabbi Adler continues:

In earlier generations, women were largely barred from participation, as were men from ignorant, impoverished families. And the women who did interact with Jewish tradition were marginal to the web.

I once wrote that "The crucial difference between Bruriah and the male sages is that no teacher claims her as a student, no student quotes her as a teacher, and Bruriah herself quotes texts but never names teachers." Consequently it was necessary to write about how one talks one's way into a tradition. And I have!

Talking one's way in involves learning the vocabulary of current participants, and stories of those who were there before one arrived. A person talking her way in has to tell shared narratives in a way that's illuminating but unfamiliar. This has been the task of feminist criticism.

Then one has to introduce new stories that the participants did not know. And show how these stories have an impact on already fraught topics. Say: the question of whether a wife is property or covenant partner. And it's an oxymoron for her to be both.

Rabbi Adler makes the case that at this point, women have talked their way in to most of the conversations about the tradition. "In Israel, a feminist orthodox group named Kolech has sued a Hareidi talk radio station that would not allow women to speak. This development is literal but also symbolic. It says that there is no corner of the tradition where women can be silenced with impunity."

Then she moves into talking about the importance of stodies in Jewish tradition. "We try not only to learn from everyone, as ben Zoma says, but we try to give-over what we learned b'shem omro [in the name of the one who taught it]. And often that means telling a story about the person who taught us. I am worried about the disappearance of storytelling. I'm worried about the atrophy of storytelling. We repeat old stories but are we telling new stories?"

All of you are making history and preserving it. But stories are not just for archives. Stories need to be told and retold so they can shape us. I worry about the number of Jews who don't have any stories about their own parents and grandparents, much less some other person who taught them something. How do we hand on evidence of how we were shaped as Jews if we transmit no stories?

A story-valuing tradition is one in which listening and telling are both important. One in which individuals and their distinctive psychologies invite interpretation. Because stories have contexts, and contexts change in our understanding of the right and good, the meanings of stories are inherently unstable.

She cites the story of Rabbi Akiva's wife Rachel, "which has always made me feel like an Indian at a cowboy movie." (That gets a rueful laugh from many of us.) "For many generations, Rachel's annihilation of self was inculcated into women as a feminine virtue, but feminists found in it a critique of the tradition which begot it. The instability of meaning in stories makes for a powerful tool to stimulate people to think. The emotional charge in stories stimulates people to care. One of our biggest challenges is to get Jews to care about their tradition."

She closes by asking: why would a learner would want a tradition? And she offers two answers.

First: a tradition is multivocal, and in that way, is a kind of model of reality that's especially appropriate for Jews. It says that reality is complex and multifaceted like its Creator. It says, as Whitman says in Song of Myself, "I am large; I contain multitudes." I contain multitudes as a learner of the tradition because I take into myself the many teachers and learners who preceded me, and the many teachers and learners around me.

Second: it's less lonely in a tradition. I experience God as El Nistater, as Isaiah 45:15 says. Truly You are a God who hides Yourself. For me, God is very elusive. And at times when God is hidden, when I pray, He/She is more accessible when my hevrutot and I tackle a demanding piece of Gemara. Together we are both enriched and comforted and sustained. Perhaps this is what the rabbis mean in the first perek of Brakhot when they say the Shekhinah is with a group studying.

She reminds us that the root of Shekhinah is shin/chaf/nun, to dwell, related to the word neighbor. Rilke has a poem called The Neighboring God, or simply, the Thereness of God. "God's Thereness is accessible to me through the texts and the arguments about what are the goods of Judaism, how to lift them out and pass them on, and the cameraderie of the people who invest themselves lovingly in this conversation."

She leaves us with a quote from someone she's been studying lately -- Rav Soloveitchik. This is what he says: (Find this in his two-volume biography of Rav Soloveitchik by Aaron Rakefet Rothkoff.)

When I sit down to learn, the giants of the mesora [tradition] are with me. Our relationship is personal. The Rambam sits to my right, Rabbenu Tam to my left, Rashi sits at the head and explains, the Rambam decides the halakha and the Ravad objects. All of them are with me in my small room, sitting around the table. They look at me with fondness. Learning Torah is not just a didactic, formal, technical experience whose purpose is creation and exchange of ideas. Learning Torah is the intense experience of uniting many generations together, the joining of spirit to spirit, and the connecting of soul to soul.

And then we move into conversation -- not so much Q-and-A as a real back-and-forth between Rabbi Adler and those who are in the room and who have responses, questions, and ideas. The ensuing conversation is terrific, though I don't take notes; I just take it in, and enjoy it, and remain grateful to be here this morning listening to this incredibly smart woman, whose work has been so formative for me, as she shares her wisdom with my rabbinic community.

Rabbi Rachel Adler: What was the Sin of Sodom?

"What was the sin of Sodom?" - Late-night study with Rabbi Rachel Adler

Visiting scholar Rabbi Rachel Adler is Professor of Modern Jewish Thought, and Judaism and Gender, at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, Los Angeles. In addition to her keynote address on Monday, she leads us tonight in a fascinating study: "There must be a moral environment for learning to occur, either in the city itself or in a resistance group. What if there is a moral vacuum? Learn why Sodom in Jewish tradition is the paradigmatic Unjust City."

Handouts include some Steinsaltz Talmud from Sanhedrin about the sins of Sodom; a smaller text which contains Biblical material and a reading from Avot; and an English text containing some of the particular ideas found in the sugya in Sanhedrin. (I'll include quotations in this post.)

We begin with an excerpt from Aryeh Cohen's 2012 Justice in the City, which uses Talmud to construct a Jewish ethics for what justice in the city would look like. "I wanted to give you the general idea first, instead of doing it slowly and by inference," said R' Adler, in case some of us drop out thanks to exhaustion! "Aryeh sets up a set of conclusions about what makes a just city based on his Talmudic research, and what I'm going to argue is that the Talmud has that paradigm in mind when it recreates Sodom as the archetypal unjust city." Here's the quote from Cohen:

Before proceeding to some particulars of the community of obligation, I will weave together the strands of the argument so far. A just city, a city that is defined as a community of obligation, is a polis in which the residents open themselves to the possibility of hearing the cries of the Stranger -- and being compelled by those cries to respond. This goes beyond directly responding to another person who crosses your path. The obligation is first, to set up our cities such that others' needs will be urgently pressing upon the body politic -- whether the vulnerability that demands our response be a result of poverty, ethnicity, lack of a home, or lack of citizenship. In other words, the city needs to be organized such that the cry of the Stranger can be heard. Homelessness must be decriminalized, economic segregation must be ameliorated.

"What did we hear from this? A just city is a community of obligation; what does that mean? For one thing, it means that you pay certain kinds of taxes," notes Rabbi Adler. "You pay for the general welfare. Also, it means that the members of the city, the people of the city, are responsible for the vulnerable among them." When you've relocated to the city, you're vulnerable for a time; there's a certain amount of time before you become obligated to contribute certain kinds of tzedakah. And when you've been there a little longer, than other obligations begin to devolve upon you.

Then we dive into what we actually see in Sodom. "What people often think is going to be the big showy sin of Sodom, if you hear it in an evangelical Christian context for example, turns out here not to be the central problem," R' Adler points out.

(We pause to read Genesis 18:17-23 in Hebrew.) "What is derekh Adonai?" asks R' Adler -- "the path of God" -- to which Avraham is committed? We agree: according to the text, it means doing justice / acting justly.

We move into commentary from Robert Alter:

To do righteousness and justice. This is the first time that the fulfillment of the covenantal promise is explicitly made contingent on moral performance. The two crucial Hebrew nouns, tzedeq and mishpat, will continue to reverberate literally and in cognate forms through Abraham's please to God on behalf of the doomed cities, through the Sodom story itself, and through the story of Abraham and Abimelech that follows it.

outcry. The Hebrew noun, or the verb from which it is derived, tsa'aq or za'aq, is often associated in the prophets and psalms with the shrieks of torment of the oppressed.

"So already we have a sense that this isn't merely an issue of a singular kinky sex act," Rabbi Adler notes. Then we move into Ezekiel 16:41, which holds that the sin of Sodom was arrogance -- "She and her daughters had plenty of bread and untroubled tranquility, yet she did not support the poor and the needy." The city is the mother and the surrounding towns are the daughters, explains Rabbi Adler. So according to Ezekiel, what is the sin of Sodom? Not supporting the needy. "It's a sin about how they constitute themselves as a city."

Someone notes that it's interesting that Ezekiel is using feminine language to speak of the city and the sisters, instead of masculine language. In our culture the dominant interpretation tends to be that sodomy is the ostensible crime here, but the Prophetic text -- by describing the city as a woman rather than a man -- almost unconsciously moves us away from that interpretation.

"Why is it that a city is called a mother?" asks Rabbi Adler. Because it should nurture and support, suggests someone in the room. "What was its function vis-a-vis the towns around it?" People banding together for the greater good. The city was the economic nurturer, where the markets and storehouses were. Another sense in which the city is a mother is, cities often had walls, so when there were raiders sweeping through the area, people from the towns would come behind the city walls. "The city was a mother in terms of being a protector."

But if this is so, suggests Rabbi Adler, then Sodom is an unnatural mother, because she doesn't nurture.

Next we move into a passage from Talmud, from Avot:

There are four kinds of men: those who say what is mine is mine and what's yours is yours, this is the average character, and some say this is a characteristic of Sodom; one who says what is mine is yours and what is yours is mine, such a person is an ignoramus; one who says what's mine is yours and what's yours is yours, such a one is a saint; and one who says what's yours is mine, is wicked.

Why, Rabbi Adler asks, is 'what's mine is mine and what's yours is yours' considered to be the quality or sin of Sodom? The room calls out: it's isolated, there's no connection, it's an insular mentality. Someone else makes the case that the sin of Sodom is a kind of not-caring, an indifference. Someone else argues that the people of Sodom, by this metric, might not all have been actively evil, but they weren't doing what they could to make things better, and that lack of action is what allows evil to triumph.

Then we move on to reading excerpts from Sanhedrin 109 a-b. This is where we spent the bulk of our time, and although the Talmudic texts can be dense, they're fascinating.

First we read a text which argues that the men of Sodom have no portion in the world to come, because, as it is written, the men of Sodom were "wicked and sinners before the Lord exceedingly." Different Talmudic voices argue: they were wicked with their bodies and sinners with their money (e.g. immoral with their bodies, and didn't give charity to those in need.) Or, wicked with their money, and sinners with their bodies. And so on. "There are no extra words [in Tanakh]," notes Rabbi Adler, so the sages went out of their way to find different explanations for why our texts tell us that the men of Sodom were both wicked and sinners.

Rabbi Adler makes the case that Lot is a kind of dark comic character, almost a parody. "The scene in which the angels are trying to get Lot to leave is a kind of comic scene, which is why you have that shalshelet in the trope on 'and he delayed.'" (The room spontaneously sings the word with its cantorial shalshelet, notes chaining up and down and up and down and up and down.) "Lot, who tries to throw his daughters to the mob, is, you might say, the only man in Tanakh who gets raped. I just note that," Rabbi Adler says tartly.

We explore a few more Talmudic notions of wickedness, e.g., the person who doesn't want to make a loan to a poor person because a shmita (sabbatical) year is coming and the debt will be canceled. This is "wickedness having to do with ways that you're stingy with your money." Then there are arguments that that the wickedness of Sodom was blasphemy, or that it was about unnecessary bloodshed.

"And then the texts escalate," Rabbi Adler says, "in telling us what was so wrong with the people of Sodom." Here goes:

The second text argues that the sin had to do with unfair work rules. Someone who had one ox would tend all the oxen of the town for one day, but he who had no oxen had to tend them for two days. The story goes that an orphan in town was given the oxen to tend, and he killed them, and argued that he should be allowed to keep their hides. The story seems to say something about the injustice of the system. A trickster figure shows up to mock power and authority by killing all of the oxen and claiming that the law of the town entitles him to profit.

The third text speaks about three unjust practices in Sodom: that someone who comes in via ferry had to pay one zuz, but someone who comes in another way had to pay two; and if someone had rows of bricks laid out, each person would come and take one and argue "I have taken only one," and if someone were drying onions, ditto. "What are the things that are unjust here?" asks Rabbi Adler. First: if you don't enter the way the city prefers you to enter, you pay a penalty. The other is, if a workmen is putting out bricks or food, everybody goes by and just takes a little bit, as though it doesn't count that the things belong to someone else.

Rabbi Adler cites Kant's categorial imperative. "I can only affirm that an act is a moral act for me if I can affirm that everybody ought to do it." (And, corollary, if it's the case that if everyone did it, things would fall apart, then one shouldn't do it oneself.) And people call out examples: sampling grapes in the supermarket, taking a pen from the office where you work, walking on the grass when there's a paved path nearby.

The fourth excerpt from Sanhedrin is about the four fictitious judges in Sodom (whose names meant Liar, Awful Liar, Forger, and Perverter of Justice.) "If a man insulted his neighbor's wife and bruised her, they would say to the husband, 'give him to her, that she may become pregnant for thee.'" (And so on.) "If someone wounded his neighbor, they would say to the victim, 'give him a fee for bleeding thee.'" What is all of this? Perversion of justice ad absurdum. "This is injustice which is so blatant that it would be funny if it weren't so awful."

The next text tells a tale of Eliezer, Abraham's servant, being attacked; the judge said "give him a fee for bleeding thee," so Eliezer took a stone and attacked the judge, and then argued, the money you now owe me (because I attacked you), give it to the guy who attacked me. Eliezer here is playing the trickster role, notes Rabbi Adler; "he's figured out how to pay the fine in the same manner that the judge has assessed it."

And Rabbi Adler describes the sixth text from Sanhedrin as the straw which breaks the camel's back: a girl gives bread to a poor man, hiding it in a pitcher, and when the men of Sodom find out, they daub her with honey and put her on the wall and the bees come and consume her. This one required us to look at the Aramaic; there's a pun between the idea that the sin is rabbah, is great; and that the sin is rivah, which in Aramaic means a maiden. (If this isn't making sense, I apologize; it's late at night for me, past midnight back home!)

"Sodom is a place that doesn't like people who are different from them, doesn't like strangers," says Rabbi Adler, "and Aryeh Cohen is going to use the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas to talk about this unwillingness to look into the face of the Other who is not just like me but is in fact Other, and I may never in fact get into that Other's brain, but that doesn't matter. That Other is my responsibility, and unless I can work toward being responsible, I'm not going to be able to be fully human."

Rabbi Adler continues:

Homosexual rape is a particularly outrageous act for the Biblical writers...but it doesn't really occupy the rabbis in Sanhedrin much at all. What they have as their last straw is enacted on the body of a woman. There's a whole kind of literary trope that has to do with violence being enacted on women indicating something about the state of the body politic.

For another example of that trope, Rabbi Adler cites Judges 19, which draws on this story in Genesis 19 in some quite horrific ways. (Trigger warning: rape survivors may wish to choose not to click on that link.)

A member of the community observes that the act of two male adults choosing to make love with one another has nothing to do with the violence of the attacks depicted in the story of Sodom, which are really about power over the powerless. In a sense, the Talmudic story about the girl who feeds the hungry, gets caught by the town, and is daubed with honey and consumed by bees is really a story about the whole city being "consumed" by its own wickedness. The city is so wicked and so uncaring that it consumes itself, by becoming a place which God chooses to destroy.

Someone else notes: the Avot passage argues that someone who says "what's mine is mine, what's yours is yours" is essentially claiming that relationship is contingent and that responsibility is contingent -- "I'll 'thou' you if you'll 'thou' me" -- a kind of quid pro quo. Whereas for Levinas, Rabbi Adler adds, we each have more responsibility to the Other than we could possibly fulfill. "There's more that needs to be done, but you just can't do it! He says that we all have to do as much as we can, and live with the mauvaise conscience for what we can't do."

Rabbi Adler continues:

What's so distorted in this sugya is law itself. And for the rabbis, that's a serious thing! Because when you distort law itself so that it's laughable, and people can only deal with it by trying to work the system, or by mocking it, you've distorted the foundation of civilization.

In closing, Rabbi Adler cites a constitutional scholar, Robert Cover, who said that law is a bridge between where we are now and altarity, a kind of different legal universe that we could envision.

For Robert Cover, law isn't just what's on the books; law is a gnomic world that you inhabit, a universe of meaning that you inhabit. It's complete and it's undergirded by all kinds of stories. And it works out values in the way that we live out the implications of that moral universe. What we see in this sugya is that it's a distortion of the moral universe. There isn't any moral universe; it's a moral vacuum.

And that, it appears, is the sin of Sodom. And that's the end of my Sunday.

January 13, 2013

Three gems from Sunday at OHALAH

1.

Although my intention on Sunday morning is to sleep in, I don't manage it. My body's still on east coast time, and even though I stayed up later on Saturday night than is my usual wont, I find that on Sunday morning I can't sleep any later than 6:30. So I shower and dress and make my way down to the lobby, where I pour myself a cup of cucumber-infused water and settle in on one of the couches to read for a little while before shacharit, morning prayer.

But my attention is caught by what's happening in the next cosy nook over: two women are gathered around a small low table, busily wrapping tzitzit -- fringes -- and tying them to the corners of a beautiful striped tallit. I pause for a moment and watch them. They are absorbed in their joyous task, and I don't think they notice me looking on. I beam at them, thinking: at what other conference in the world does one run across women tying tzitzit on a tallit in a hotel lobby?

2.

I go to lunch at the Dushanbe teahouse with three friends. The painted ceiling, the pots of mango ginger black tea, conversation about hashpa'ah / spiritual direction, and what it might be like if the hashpa'ah program were something everyone in the ALEPH ordination programs did, and cooking, and being here. The simple pleasure of good food, good conversation, togetherness.

Atthe end of the meal, Evan breaks into Brich Rachamana, and we four sing the round together, our voices interweaving and blending. Perhaps because this is Boulder, which is a little bit granola-crunchy; Boulder, home of Naropa and Reb Zalman and a lot of spiritual goings-on -- no one at the teahouse appears to mind or even to notice the foursome in the corner singing an obscure Talmudic grace after meals. Above us, the painted ceilings gleam.

3.

Reb Zalman is speaking to the musmachot -- this year's crop of ordinees -- and he tells a story which, as he begins it, I realize he told at my smicha two years ago and I had forgotten in the interim. It's about a man who lost his beautiful snuff box in a cemetery and was crying about it, and the goat who lived in the cemetery and who had beautiful long spiralling horns said "here, take some of my horn," and bent down to give him some of his horn to make a new snuff box.

And the man's new snuff box was so beautiful, and it made the snuff inside it so heavenly, that soon everyone in town came to the cemetery to demand some of the horn -- which had reached all the way to the heavens; it provided a taste of the sweetness of Eden -- and soon the goat with the beautiful spiralling horns was worn down to nubs, and there was no one left who could hold up the heavens and reach the sweetness of Eden. Don't do this to your rabbis, Reb Zalman cautioned us. Don't wear them down to the nubs. Let them reach up to the heavens and draw sweetness down.

Liebster Award meme

I've been nominated for a Liebster award. This is a meme, a cross between a chain letter and an award given by bloggers to bloggers; it's meant to be given to an up-and-coming blogger who has fewer than 200 followers. (The word "Liebster" comes from German and means "favorite" or "beloved.") I appreciate the nomination, though I'm not entirely sure I qualify; near as I can tell I have somewhere in the neighborhood of 2000 subscribers, and I'm not sure that after nine years I can call this blog "up-and-coming" anymore! That said, I appreciate the spirit of the nomination -- and I'm happy to answer Rev Allyson's questions, because they're fun. Here's what she asked:

I've been nominated for a Liebster award. This is a meme, a cross between a chain letter and an award given by bloggers to bloggers; it's meant to be given to an up-and-coming blogger who has fewer than 200 followers. (The word "Liebster" comes from German and means "favorite" or "beloved.") I appreciate the nomination, though I'm not entirely sure I qualify; near as I can tell I have somewhere in the neighborhood of 2000 subscribers, and I'm not sure that after nine years I can call this blog "up-and-coming" anymore! That said, I appreciate the spirit of the nomination -- and I'm happy to answer Rev Allyson's questions, because they're fun. Here's what she asked:

1. What role does religion play in your life?

Judaism informs pretty much everything I do. I see the world through the lenses of Torah and Jewish texts, I measure and sanctify time in Jewish ways, I connect with God through Jewish tools. Oh, and I'm blessed to be able to serve the local Jewish community as a congregational rabbi, so religion plays into how I earn my daily bread, too.

2. What's your favorite television show, and why?

There's some great television storytelling out there, so this is a bit of a tough one, but I think I'm going to go with Friday Night Lights. Amazing storytelling, characters who feel real, a terrific depiction of mature married life, and a long, slow build over the course of five seasons. It's also a beautiful look at smalltown life (both the positives and the negatives thereof), and the cinematography is stunning and often makes me nostalgic about my own Texas childhood (though my own childhood didn't involve really any football at all.)

3. What was your favorite subject in high school?

It was a toss-up between Biology, Latin, and English.

I had terrific teachers in all three subjects. I was certain I was going to major in one of those three once I got to college. But then I took my first religion course, with the inimitable Thandeka, and that changed my life.

4. Coffee, tea, or other? Why?

Coffee and tea, please! I like them both.

5. What is your favorite ethnic food?

I have to choose just one? I'm a huge fan of Ethiopian -- though it's not something we can get around here, and we've never learned to make injera, alas, so we've never explored cooking Ethiopian on our own. But I've pretty much never met a cuisine I didn't like. We cook a lot of Tex-Mex and Indian and Thai in our house.

6. Have you ever baked bread from scratch? Why or why not?

Oh, goodness, yes! There was a period of time when I used to bake challah every Friday before Shabbat. I don't do it anymore (both because I work on Fridays now, and because my friend the baker at the A Frame bakery makes such delicious challah) but I do love baking bread. Lately I've been falling in love with baking sourdough. A dear friend gave me a North Adams sourdough starter, and I've been baking with it very happily when I can make the time.

7. Why do you blog?

Writing is part of my spiritual practice, and sharing that writing with the world encourages me away from solipsism and into conversation/community. I like sharing the things I love -- Torah, poetry, theology -- and blogging offers me a way to do that.

8. Is Doctor Who a silly show or a deep commentary on the world today?

Can't it be both? It can certainly be silly (especially in some of its earlier incarnations), but I think it also offers a window into some big questions: what does it mean to be human? If we could travel through time, what would we want to see, and what might we wish we could change? Is it our technology which makes us great, or our ability to think and feel and love? I admire the Doctor's relentless curiosity and his love of humanity.

9. What's your opinion of social media in general (Twitter, FaceBook, G+, etc)?

They're useful tools for connecting and communicating, though they're also terrific procrastinatory devices. (And the difference -- whether I experience them as ways of connecting, or as ways of distracting myself -- is entirely in me, not in the social media platforms themselves.) I find that I enjoy connecting with people through those various media, but I've also learned that I'm happier when I'm also engaging with people in more in-depth ways, which often means through long essays / blog posts instead of or in addition to the short stuff.

10. If price were no object, what would you want for your birthday?

Travel! There's nowhere in the world I wouldn't enjoy visiting. I'd particularly love to visit Turkey, where I have never been (I hear beautiful things about Istanbul.) I'd love to see more of Africa -- I've only ever been to Ghana, where Ethan used to live, and I really want to see more of that vast and amazing continent. I'd love to go to Japan someday, particularly Hokkaido.

And it would be grand to be able to travel to visit far-flung friends on the west coast of the US, too. I've never been to Portland, Oregon, and would love to go there someday. I have a good friend who's now serving as a rabbi in Bozeman, Montana; I drove through Montana in 1996 on a cross-country jaunt but haven't been back since, and I'd love to find a way to get back to big sky country.

11. Where do you read the news? Why?

Most often The New York Times. I trust their editorial choices and I always learn things from reading them. Ditto The Christian Science Monitor. I learn a lot from listening to NPR.

And sometimes I spend time at the BBC, which offers a different perspective than I tend to see in American papers. I also try to at least skim Global Voices Online for reminders of the many stories and issues and ideas unfolding elsewhere in the world.

Now I'm meant to identify eleven other small-readership blogs and nominate them, and ask eleven questions for those bloggers to answer. (Or, in some versions of the meme, it's seven bloggers / blogs / questions.) I'm going to do something slightly different, though -- consider it a modification of the original meme. Here are five questions. If you have a blog and you want to answer these questions, please consider yourself nominated! Answer the questions in your space, and then drop a comment here to let me know you've done so.

1. What's your favorite book?

2. With what fictional character do you most identify?

3. If you could throw a dinner party and invite five people, real or fictional, from any moment in human history, who would you invite?

4. What's your favorite place to pray / meditate / engage in spiritual practice?

5. What's something you're hoping for in 2013?

January 11, 2013

In which Drew blesses me with peace (after a fashion)

Drew enjoys a Shabbat PB&J.

First we play peekaboo with the candles. I cover my eyes, Drew covers his, and we peek at each other and grin. I sing the blessing over the Shabbat candles, sometimes rushing a little bit when Drew imperiously tells me to stop singing now.

Then we bless the fruit of the vine. Drew raises his sippy cup of watered grape juice, I raise my wine glass, we clink them together and say "cheers," and I sing the one-line blessing over wine. After it's over, Drew likes to sing out with "a-a-men."

Then we bless the challah we picked up at the A Frame bakery earlier in the afternoon. I uncover it and raise it up and sing the hamotzi, and Drew sings a-a-men. (If I forget, and sing it myself, he chides me: "No, mommy! I want to do it!")

And last of all, I bless him. I go over to his side of the table and I say the words of the priestly blessing in English and Hebrew:

יְבָרֶכְךָ ה' וְיִשְׁמְרֶךָ , May God bless you and keep you. יָאֵר ה' פָּנָיו אֵלֶיךָ, וִיחֻנֶּךָּ , May God's face shine upon you and be gracious to you. יִשָּׂא ה' פָּנָיו אֵלֶיךָ, וְיָשֵׂם לְךָ שָׁלוֹם, May God lift up God's face to you and bring you peace.

And then I kiss him on the head and tell him I'm proud of him.

Tonight, a few moments after we've concluded our blessings, Drew turns to me and solemnly says, "And last, I blesses you." This is new and adorable, and I beam. "I blesses you and bring you piece of challah. Do you want a piece of challah, mommy?"

Of course. He has no idea what "bring you peace" means -- as far as he can tell, I'm blessing him that he might receive a piece of yummy bread. All I can do is laugh and tell him that yes, I absolutely do, and also, he's the best. Which he is.

A Rebbe Dream

I am carrying my son

around a bus filled with scholars:

rifling through my carry-on

in search of cheese sticks

and bananas, exploring

the wooden deck and silk flowers.

Someone ushers in my rebbe

proclaiming He's just received

a clean bill of health!

His beard is trimmed

and there's spring

in his step.

I shake hands

with a young Madeleine L'Engle,

perhaps forty, blond ponytail

and kind smile. I read email

from a Sufi sheikh who's sorry

he isn't able to join us.

Reb Zalman kneels beside me

and confirms I'll transcribe

all of the teachings,

asks what he can pay me.

It's a freewill offering, I reply

and he suggests $84.

(Only in the morning

well after I've woken

when I look up the number

on my gematria app

do I discover it equals

the Hebrew for dream.)

He moves on and I whisper

to a nearby friend

how does one come to look

fifteen years younger?

He hears, across the distance,

and laughs.

(Image: Reb Zalman's last Accord visit, photo taken at the old Elat Chayyim by Jeri Berc, 2006.)

(Image: Reb Zalman's last Accord visit, photo taken at the old Elat Chayyim by Jeri Berc, 2006.)

This poem arises out of a real dream I had a few nights ago. I wrote

down everything I could remember of the dream once I was at my computer.

The strange number chosen by the Reb Zalman in my dream piqued my

curiosity, so I looked it up on iGematria; when I discovered that one of

the words which matches with 84 is חלום, dream, I gave myself the

shivers, a little bit.

I'm still not sure what to make of the dream. I remember thinking, during the dream, that I felt lucky to be able to move seamlessly between taking care of my son and learning from great teachers. (Madeleine L'Engle was one of the teachers on this mysterious Torah bus; another was Rabbi Shefa Gold.) I welcome responses both to the dream, and to the poem which the dream sparked!

January 10, 2013

Reprint: Interview with Rachel Adler (in anticipation of OHALAH)

Back in early 2009, I interviewed Dr. Rachel Adler for Zeek. My interview with her ran in the spring 2009 print edition of Zeek, the Sex, Gender, and God issue. (I posted about that here at the time.) Zeek no longer does a print edition, and I'm not sure it's possible to buy that back issue anymore, so in advance of Rabbi Dr. Rachel Adler's keynote presentations at the OHALAH conference next week, I'm reprinting the interview I did with her. (As it happens, I did the interview by phone from OHALAH, so there's a sense of things coming full circle for me!)

Rachel Adler is one of the foremothers of Jewish feminism. In 1971, she published an article entitled "The Jew Who Wasn't There: Halakha and the Jewish Woman" in Davka magazine. Many now consider that article to have been the springboard that launched Jewish feminism into the world.

Adler's "Engendering Judaism" is a germinal classic of Jewish feminism. She was one of the first theologians to read Jewish texts through the lens of feminist perspectives and concerns -- work she's still doing today, as a professor of Modern Jewish Thought and Judaism and Gender at the School of Religion at the University of Southern California and the Hebrew Union College Rabbinic School.

I spoke with her from the hallowed halls of the Hotel Boulderado where I was attending the annual meeting of Ohalah, the Association of Rabbis for Jewish Renewal -- a profoundly feminist organization which owes its existence in part to her work. We talked about entrails (she's working on a reading of Mary Douglas' work on Leviticus), congregational politics, the new Hebrew edition of "Engendering Judaism," and her hopes for the future of Jewish feminism.

Our conversation made me realize just how far we've come, and how grateful I feel to be living and learning in a time when Adler's work is part of the liberal Jewish canon. --Rachel Barenblat

ZEEK: Your roots are in Orthodoxy; today you teach at Hebrew Union College. Can you give us a nutshell version of how you moved from point A to point B?

ADLER: Actually I'm a 5th generation Reform Jew, but became Orthodox in my late teens. I was Orthodox for more than twenty years, but eventually returned to Reform Judaism. I joke that I am a round-trip baalat teshuva.

ZEEK: "Engendering Judaism" came out in 1998 -- more than ten years ago now. Do you still consider it to be a radical text?

ZEEK: "Engendering Judaism" came out in 1998 -- more than ten years ago now. Do you still consider it to be a radical text?

ADLER: Yes. In Engendering Judaism I propose a basis for a progressive halakha -- a pro-active, rather than reactive, halakha which is formed at the grass roots level. I also propose a wedding ceremony which is egalitarian and halakhically feasible. And I propose that our sexuality is part of our divine image. All of these things still strike my students as radical.

ZEEK: You've argued that until "progressive Judaisms" attend to the impact of gender and sexuality, they can't engender Jewish life in which women are equal participants. Have you experienced hostility to this view, either from within progressive Judaism or from folks outside of this sphere?

ADLER: Orthodox Jews don't make pronouncements on what progressive Judaisms need to be more progressive. It's progressive Jews who sometimes pay lip service to the need for egalitarianism, and then when it comes to think tanks or executive positions in Jewish institutions don't include women.

ZEEK: You've raised the point that relegating gender issues to women alone perpetuates a fallacy about the nature of Judaism. Thinking in terms of "Women in Judaism" suggests that women are a kind of add-on to the normative body of Jewish tradition, in maybe the same way that studying "Women's literature" implies that literature writ large is necessarily in the purview of men...

ADLER: Actually I footnoted this point. It was made by another scholar, Miriam Peskowitz. Most academic disciplines now view gender as an area for scholarship by both women and men. That makes sense, since gender,both feminine and masculine, is a changing variable, affected by social and historical context.

ZEEK: You write, "Engendering Judaism requires two tasks. The critical task is to demonstrate that historical understandings of gender affect all Jewish texts and contexts and hence require the attention of all Jews. But this is only the first step. There is also an ethical task." This puts me in mind of Rabbi Akiva's response to the question of which is greater, study or action: "study, if it leads to action." What kind of action do you hope our continuing study of these issues will spur us to undertake?

ADLER: Understanding that gender practices change according to social and historical context means that we could intentionally reenvision and reshape gender practices. What would we want to create? A world where no female babies die of malnutrition because they are fed last? A world where no women are disadvantaged simply because they are women and not men? A world where women entering a profession such as law, medicine or, for that matter, the rabbinate, doesn't cause masculine flight to some other profession? Or the activity of women in congregations or in the pulpit doesn't make men take their marbles and go home? A world where there are many shades of gender and sexuality, not just two?

ZEEK: On a related note, you've written that you're interested not only in critiquing androcentric structures but in healing Judaism -- that your goal is not judgement but restoration. Does this tie in with the ethical task I just mentioned?

ADLER: Absolutely. Judaism is not a system on which I'm passing judgment from a distance. It is my home in the universe. I'm concerned that I and other women be full and equally privileged residents in our home.

ZEEK: You write, "If I were not a feminist, I would not feel entitled to make theology." How did you come to self-define as a theologian?

ADLER: I have to say, when I wrote "The Jew Who Wasn't There," which is the first piece of theology I wrote, I really didn't know what to call it. People around me seemed to have a lot of things to call it -- like 'pernicious trash' -- but I didn't know what to call it! It was later, when I began reading theology, that I realized that I had written theology.

And it was an awesome realization. Because I didn't know of any women who had written theology. I certainly didn't know of any Jewish women who had written theology. Later I discovered all of the Christian women theologians, and then of course there was Judith Plaskow's work. Judith was trained as a theologian. Though she was trained as a Christian theologian, which created a different set of problems. She got her doctorate at Yale--

ZEEK: Which was a Christian-focused religion department at that time...?

ADLER: Yes. Of course they're a wonderful Judaica department now, but there was not really much when Judith started her theological education.

ZEEK: Is feminist theology necessarily a theology of immanence?

ADLER: No; I don't think so. I realize I'm in the minority on that! But I would like to believe that feminist theologies can involve both immanence and transcendence. Because I think that as human beings, we live both in an immanent mode and we transcend.

ZEEK: it doesn't have to be so binary; there's a way of bringing the two together.

ADLER: I think there's a way of balancing, and I think that there's a kind of a spectrum of relational stances that we and God can have vis-a-vis one another. But my problem with radical immanence is that it becomes difficult to distinguish from solipsism.

ZEEK: You write about the need to enrich and diversify our liturgical language. In my own practice I've shifted first from the masculine God-language of my childhood, to the feminine terminology of my college years, to alternating between them, to a linguistic hodgepodge that draws often on nongendered metaphors (source, wellspring, breath) -- which is fine when I'm davening alone, but isn't always comfortable for others. To what extent do you think we need to be concerned with the ways in which linguistic creativity (especially in Hebrew, a language most liberal Diaspora Jews don't speak fluently) can throw daveners for a loop?

ADLER: It's a difficult question! Partly because when you're talking about prayer, you're talking about a need to communicate with sincerity with the divine. And you're also talking about a practice that has ritual dimensions. So that part of what we do to put ourselves in the space where we can communicate with the divine is to use language in a highly-patterned way to alter our consciousness. And the predictability of that language is partly what does it for us.

So it's very hard to help people find new God-language. Because its newness is very grating. And it's seldom that we find language that is very compelling to us. I've just been looking at the new book of women's prayers by Aliza Lavie. It's been translated and it's also got the Hebrew. These are things women wrote in Hebrew, and it makes a big difference -- there are a few prayers in there that I was tremendously moved by, and felt, 'this is something that has been missing for me that I've always needed and I never had the right prayer and here it is!' I think one thing that makes that easier is if we work on our Hebrew. And another thing that makes it easier is having translations that are really powerful and graceful translations.

I think sometimes we put up with a lot of mediocre prayers. It's amazing to me when I realize that the book of Isaiah, written basically by two and some say three different schools of prophecy -- it's as if there were three committees who produced Isaiah. And I think to myself, "committees have really gone downhill since Isaiah."

ZEEK: I think of something like [the Reform movement's new siddur] Mishkan Tefila, which we've begun using at my shul; there are things I love about it, and also things which make me crazy. It definitely feels like it was written by a committee.

ADLER: There was a decision made to try to solve the problem of gender and God-language by using language that was neutral. And what that does is, it kicks the language up a level of abstraction, and it disembodies the language. It does not appear to be masculine God-language unless you're reading in the Hebrew, in which case a lot of what you're reading appears to be masculine God-language because there isn't the choice of neutrality in hebrew. But with the neutrality, you get a kind of juicelessness. If you use "Mother" or "Father," there's something really immediate and primal-feeling there. If I use the word "Parent," it's a neuter word but it doesn't have the kind of emotional charge.

ZEEK: You write "A story is a body for God." I wonder whether the same might also be said of poetry, and whether we're generally more comfortable accepting new or uncomfortable theological language in poetry than in prose? Do you think that if there were new liturgy being written which was great poetry, maybe it would be more palatable for people?

ADLER: Some of the language in this Aliza Lavie volume is very impressive to me. So don't lose hope! There are wonderful things happening. They just happen slowly. Think about it: all of this has been very fast, if you think about the levels at which things usually change in Judaism. This has been a whirlwind. Women becoming fully entitled and fully responsible Jews.

ADLER: Some of the language in this Aliza Lavie volume is very impressive to me. So don't lose hope! There are wonderful things happening. They just happen slowly. Think about it: all of this has been very fast, if you think about the levels at which things usually change in Judaism. This has been a whirlwind. Women becoming fully entitled and fully responsible Jews.

ZEEK: Is there anything in "Engendering Judaism" that you would write differently now, or anything you would add? Was there a temptation to add an extra chapter?

ADLER: What I would like to add if I do another edition of the book is a ceremony for dissolving a brit ahuvim. I gave some directions, but I didn't really give a ceremony, and I would like to do that. Otherwise, no, I think it is what it is at this point. Though there may be other things that I would write.

ZEEK: Is there anything different in the new Hebrew edition that's not in the English edition?

ADLER: No. It's a good translation. My friends who have a better ear for Hebrew style than I do keep telling me that it's really interesting Hebrew, so I'm encouraged by that! But no, it hasn't been amended in any way.

ZEEK: It just came out in December, so I imagine it's still rippling in the pond; do you have a sense yet for how people are responding to it in Israel?

ADLER: I had an interview in Ha'aretz, and they referred vaguely to the people who don't agree with you or the people who are not in favor -- I'm not sure exactly what language they used. But it was odd, because I usually don't get to hear that kind of criticism. In fact, the reviews here were almost uniformly good reviews.

ZEEK: What's the project of your heart these days?

ADLER: Right now I'm working on a book for laypeople about suffering. It's tentatively titled "Why we suffer: a guide to choosing answers." And what it will do is, give a number of ancient and modern ways of answering that question, why do we suffer. And give an analysis of each of those options. For those who are in the first throes of grief, they just want it to stop; but when you get some perspective, you become curious about 'why?'

ZEEK: Was there something in particular that sparked that project?

ADLER: Yes. My mother died after being ill with dementia for five years. It was a protracted death from dementia. Most of that time she could not communicate, could not move. It was very difficult to tell if anything was happening in there.

ZEEK: That would open up questions of theodicy if anything would!

ADLER: Yes. At the time, I would visit her and I would sit with her an entire weekend and she would maybe say one word to me. And the word would either be "why" or "help."

ZEEK: I'm sorry you went through that.

ADLER: Well, part of my answer is, it's part of being human. And what it is in us that makes us suffer is pretty much the same as what it is in us that makes us able to have pleasure and joy.

ZEEK: Have you heard the accusations that Judaism is being "feminized," and that this is why in some communities there are now more women active than men -- e.g. we're driving the men away? (What do you think about that? I suspect I can guess, but I'd love to hear your take.)

ADLER: I've listened to people talk about this, and I've read people's writing about this, and two things occur to me. One is that we're not talking about men who are highly educated Jews. They really have the same grasp on the tradition that they've always had. We're talking about men who have had the power in liberal synagogues but who don't necessarily have a good Jewish education.

What happened with women is that women came in and started to acquire that Jewish education, and started trying to acquire those skills, and what happened -- at least from some of what I hear, what I read -- with the men is, they feel at a disadvantage. The problem is, you don't admit ignorance, you can't learn! If it's a matter of being in control of the synagogue as an institution and now men no longer are able to do that all by themselves, that really should not be so terribly traumatic! There really aren't other places in society where men are able to have social activities that women are totally absent from. Why should the synagogue be any different in that way?

So if it's a question of "the men didn't like women being active in the synagogue so they took their marbles and went home," I think that we have to make them feel that there's a place for them in the synagogue. But I don't want to leave the women out so that men can try to reclaim some kind of patriarchy somewhere. That doesn't make sense.

ZEEK: At the beginning of the epilogue to "Engendering Judaism", you write, "Seeds contain both the past and the future. As legacies from the dead, they reproduce the world. As pledges to the future, they change it. Every seed points to some future seed that will both incorporate it and differ from it." This puts me in mind of Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi's writings about what he calls "integral halakha," which needs to maintain continuity with the past and also evolve from it -- to include and transcend what came before.

ADLER: All halakha evolves. I think the question is, who gets to participate in that process? And whose stories get to be part of the data that evolution needs to take place. I would like to see a halakha that men and women engender together. One that would draw the best from all of us.

ZEEK: When it comes to feminist halakha, whose work would you recommend?

ADLER: One of the most brilliant people writing about halakha today is Tamar Ross. I agree with where she ends up though I don't see why she had to go to such lengths to get there! She ends up with the notion of an evolving Judaism which she traces back to Rav Kook; and I don't see that what she ends up with is that different from what Zalman Shachter-Shalomi would say, or what Reform Judaism would say about the evolution of Judaism. But I have tremendous respect for her acuteness. And the philosophical precision with which she's able to talk about halakha.

ZEEK: Is there anything else you'd like to talk about which I haven't asked?

ADLER: The thing that I would want to say is that when I wrote "Engendering Judaism," for the parts of it where I dealt with rabbinic feminist hermeneutics or Biblical feminist hermeneutics, I really felt privileged to deal with what was already a tremendously rich literature that women had created on these topics. And now there's even more. And it's wonderful! It's wonderful to run barefoot through.

ZEEK: That's a great image.

ADLER: I think about it because sometimes I think of how hard it was for the first generation of women who became Talmudists to do that. And there are a lot easier ways of doing it than the way I did it, which involved a lot of crying out of sheer frustration. But to think that there are now all of these women who are able to be playful with these texts that were tremendously oppressive to women...! I just find that a delicious irony.

ZEEK: And maybe a sign that we're moving in the right direction. May it continue.

January 9, 2013

The last toddler house poem

CHANGE IN THE TODDLER HOUSE

You run and climb, sit backwards

on your little chair, ascend stairs

one footfall on each step. You sleep

in the big-boy bed your daddy made

and we're about to remove the rail.

You speak in compound sentences:

remember when we went on a big airplane

to Nonni and Papa's house, to Texas;

when I get bigger I won't try quesadillas!

You have fervent opinions

about which book to read next

which blanket sleeper to wear

which song I should sing and when.

You're a magic beanstalk, tall

as a four-year-old, and when you kick

the wall beside your bed

it sounds like an officer pounding

at the door. You're not a toddler

anymore: you're a child, a boy,

a youth. Most nights now you settle

at the end of your bed for our routine

because on my lap you sprawl

from my shoulders to my knees.

You're uncontainable. Daily now I pray

for the good sense to fence you in

only as much as you need, to enjoy

your bedtime-forestalling antics

(as though you really thought

your head goes at the foot end!)

to let you into my lap anytime you ask

because you do give super hugs

and someday you'll roll your eyes

instead of clambering all over me

but not yet, thank God, not now.

I think this is the last of the so-called Toddler House poems. I was looking back over those collected poems this morning and realized that they chronicle a moment in Drew's life which is already over; he's not a toddler anymore, and hasn't been for some time. So I drafted this poem to serve as the capstone to that small collection. I'm not sure what the collection's fate will be -- a wee chapbook, a sequel to the not-yet-published (but due this year!) Waiting to Unfold? -- but I'm glad to have the poems as a scattered chronicle of the toddler year(s).

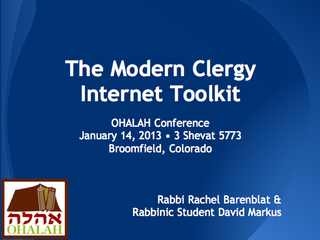

Clergy's internet toolkit at OHALAH

Next Monday afternoon at OHALAH (the annual conference of the association of Jewish Renewal clergy, which is also named OHALAH) I'll be co-presenting a session for the first time with my friend David. The session is titled The Modern Clergyperson's Internet Toolkit, and here's how we've described it:

What does it mean to minister to people online? How can Jewish clergy best use Facebook and G+, Twitter, and blogs to reach out to our communities and to stay connected with our chevre and those to whom we tend...and what is the shadow side of all of these technologies; what are the challenges and potential pitfalls of being plugged-in? Is it possible to provide pastoral care via Skype? (How about via Facebook?) How careful do we need to be in monitoring our own online presences? What messages do we send when we are (or are not) available digitally 24/7? What are the unexpected blessings of being clergy in this brave new networked world? Can cultivating online presence tangibly support brick-and-mortar communities, and if so, how?

Panelists Rabbi Rachel Barenblat (Velveteen Rabbi blog / Velveteen Rabbi website) and David Markus (Reb David) will each offer brief prepared remarks, and then will open these questions up for conversation. They will moderate a roundtable in which participants around the room can share their best practices and their experiences and their resources.

I'm looking really forward to this. David and I have prepared a solid presentation, and it'll be interesting to see what insights and questions are raised by other folks in the room. We'll be talking about internet presence and how it's no longer optional for clergy, about some of the questions and cautions raised by online pastoral work and online connections, the blessings of blogging and of (potentially) reaching the whole wide world, some case studies in online pastoral care and online clerical interaction, the legal implications and the shadow side of this brave new world, and what we've found (and others have found) to be best practices in this realm.

If you're going to be at OHALAH, I hope you'll join us. Handouts, and a copy of our slides, will be made available at the OHALAH website after the conference is over, and if someone's able to record audio of the session, we'll post that too -- though I'm pretty sure that all of those resources are password-protected for conference registrants only. (But hey, it's not too late to register to join us at the conference!)

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers