Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 157

May 18, 2014

On engraved-pathways and connective-commandments: Bechukkotai

"If you follow My laws and faithfully observe My commandments..."

"If you follow My laws and faithfully observe My commandments..."

These are the opening words of this week's Torah portion, Bechukkotai, as rendered in the standard Jewish Publication Society translation. Why mention both "laws" and "commandments" -- isn't that redundant? Actually, not in the original Hebrew. Torah uses different words for different kind of mitzvot. Specifically, here, we have the terms chukim and mitzvot.

The word chok means a mitzvah for which we do not know the logical reason. (They're often juxtaposed with mishpatim, mitzvot for which the reason can be understood. Caring for the needy, for instance: it's clear why that's the ethical thing to do.) Kashrut and brit milah are two big chukim. No one who engages in these mitzvot does so for rational reasons. These are mitzvot which ask us to trust in practices we can't understand.

My teacher Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi teaches that the word chok comes from the root meaning "engraved." He writes:

In order to transmit an engraved message, the medium of transmission must give up something of itself: this is what the chipping-out process of engraving entails. And the medium of transmission here is us. More than the other types of mitzvot, the chukim ask for a higher level of surrender to a will that is not our own...[and] I have found that they bring me closer to the realization of God.

Surrender is not always easy for moderns. I will admit that I struggle with the spiritual value of surrender. For women in particular, there is deep spiritual wisdom in learning how and when not to surrender -- how and when to prioritize our own needs and desires. And yet I can't deny Reb Zalman's point that sometimes giving myself over to a practice (such as wearing tefillin on weekdays) impacts me in deep spiritual ways.

Wearing tefillin changes me. Every time I do it, I feel different. I can't rationally explain why that is, but I know that it's true. When I lay tefillin, also, it leaves a mark on me for a while afterwards. I have to wind the straps tight, or it falls off the arm -- which means that when I unwind the straps, there is a spiral on my arm. The action engraves itself on me, and even once that engraving has faded, it has an impact on my actions and my choices and my heart.

The English word "laws" doesn't seem to quite cut it. Let's try "engraved-pathways," and look at that first verse again:

"If you follow My engraved-pathways and faithfully observe My commandments..."

We usually translate mitzvot simply as "commandments." But the Talmud teaches that the word mitzvah can also be linked with the Aramaic word צוותא / tzavta, "connection." A mitzvah isn't just something which God commands us to do. It's an act which connects us. Mitzvot connect us with our ancestors -- with our descendants -- with the world around us -- with the source of meaning and mystery which we name God.

Perhaps the English word "commandments" doesn't reflect the Hebrew deeply enough. Let's try "connective-commandments." And let's skip ahead a few verses and see what the Torah teaches will happen if, in fact, we do these things which God asks:

"If you follow My engraved-pathways and faithfully observe My connective-commandments... I will be ever present in your midst: I will be your God, and you shall be My people."

This, Torah tells us, is the reward for allowing our lives to be engraved with the furrows and pathways of religious practice, the grooves of gratitude and ritual which we carve and through which our hearts and minds learn to flow. This is the reward for practicing the mitzvot, which connect us in to our deepest selves and out to our community around the world, back through the chain of generations and forward to the descendants we can't yet imagine. If we do these things, God will be present with us. The active covenantal relationship between us and God will flare to life and stay alive within us.

This week's Torah portion also tells us that if we follow in these pathways, the rains will fall in their season and we will have abundance. For many years, the Reform movement looked askance at verses like these, seeing in them a kind of supernaturalism which belied the reality that rains and good harvests -- good fortune and blessing -- come to everyone, or they don't, but either way, they don't seem to come only to those who lead ethical lives. We all know that bad things sometimes happen to good people, and vice versa (whether or not those people live a life of mitzvot); how then can we assert that our following of mitzvot impacts the rains and the harvest?

But in an era of increasing awareness of climate change, we may find new resonance in these verses. When we -- writ large; we, the human community -- act in awareness of our connections with each other and with our Source, then we are good stewards of our planet. And when we do not, we contribute to a changing global climate increasingly characterized by floods like the one in Boulder earlier this year, drought like the one my parents have been experiencing in Texas in recent years, even the melting of the western Antarctic ice sheet which appears, scientists say, to now be inevitable.

But we can always choose to act in mindfulness of our connections. Our connections with each other, with our tradition, with our planet. When we do these things, we let God into our lives. And when we give ourselves over to the wisdom and practices of Jewish tradition; when we use the connective tools of our tradition to link ourselves with our generations and with our source; those choices will create their own reward.

This is's the d'var Torah which I offered yesterday at my shul. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.) Image: candlesticks engraved with the words שבת שלום, "Shabbat shalom."

May 16, 2014

Listening across our differences

Sometimes when I look at my Twitter stream, and see the wide (and passionate) diversity of opinion which my friends express about Israel and Palestine, I despair of common ground ever being forged. If I can't imagine my friends on the one side really hearing my friends on the other side, how can it be possible that those who disagree with each other even more strongly than my friends will ever break bread together in peace?

Sometimes when I look at my Twitter stream, and see the wide (and passionate) diversity of opinion which my friends express about Israel and Palestine, I despair of common ground ever being forged. If I can't imagine my friends on the one side really hearing my friends on the other side, how can it be possible that those who disagree with each other even more strongly than my friends will ever break bread together in peace?

Ethan has written a fair amount about the dangers of homophily, and about the echo chamber which arises when one is only exposed to limited opinions and perspectives. (Here's an early blog post on the subject; for more, I highly recommend his book Rewire.) I try hard to stay open, and to hear the voices of people who are different from me -- and I know that there are so many axes of difference that I'll always be working to broaden my hearing.

Am I listening to women as well as to men? Am I listening to people of color as well as to white people? Am I listening to transgender folks as well as those who are cisgender? Am I listening to people from the global South as well as people from the global North? Am I listening to people who are poor as well as people who are wealthy? (And so on, and so on.) And -- what do I do when the voices to whom I am listening are in tension with one another?

Listening can be a powerful and active thing. I learned this during my year as a student chaplain at Albany Medical Center. The greatest gift a chaplain can offer isn't "the perfect prayer" or "the right teaching," but real and whole presence. When I sit by someone's bedside, and open myself to hearing who they are and where they are, I manifest the listening and loving ear of God.

It's a lot easier to do that when I'm sitting by a hospital bedside than when I'm comfortably ensconced behind my desk encountering someone else's version of the news. And yet the opportunity to respond with openness and compassion is as real on Facebook and Twitter as it is when I'm ministering to someone who is suffering. Beyond that, while we don't all have the holy opportunity to engage in formal pastoral care, we all have countless opportunities to listen every day.

Ethan makes the case that homophily -- listening only to people like ourselves; that phenomenon referenced in the saying "birds of a feather flock together" -- can make us ill-informed about the world. Being a rabbi, I'm inclined to frame that same truth in religious terms. I think we have a religious obligation to broaden our sphere of understanding. Every person in the world is made in the divine image. No matter where they're from, or where they fall on the political spectrum, or where we might agree or disagree.

When we listen to people who are different from us (and different from each other), we can open connections between one experience and another, one understanding of the world and another. We encounter different facets of the infinite diversity of creation. The shema, which we recite every day, calls us to this work of listening. Listen up, y'all, it exhorts us. We are in relationship with the Source of All Being! And that Source is One. It's our job to listen to the unity which thrums behind our diversity.

There's a Talmudic story which teaches that the difference between God and Caesar is that Caesar puts his image on every coin and they are all alike -- whereas God puts God's image on every human, and we are all different as different can be. (For a beautiful drash on this, I commend to you Rabbi Arthur Waskow's God & Caesar: the Image on the Coin.) This is, as my programming friends would say, a feature and not a bug. It's not a flaw or an accident -- it's part of what makes creation so incredible.

And because we are so different in so many ways across this wide world (and even across narrow subsections of our world!), sometimes we disagree. I struggle with that sometimes. Like many clergy, I'm a born peacemaker, and I've had to learn to resist the temptation to put a "band-aid" over disagreements in a facile attempt to bring healing.

It is not always easy to hold a posture of openness to differing perspectives and views. Sometimes it feels like my own heart has become the container where opposing voices are duking it out. (Those are generally times to step away from the computer and ground myself in cooking, or reading a book to our child, or in poetry and prayer.)

But I think that cultivating that posture of spiritual openness -- developing the habit of keeping one's heart and mind open to other perspectives, even when (especially when) those other perspectives challenge us -- is some of the most important inner work we can do. And if there come moments when I look at our heartfelt differences of opinion and I feel despair, then I have an opportunity to pray that I might soon be returned to the ability to look at our differences and see opportunity for connection again.

Related:

Being Meir, Zeek magazine, 2013

The spiritual work of wrestling with the both/and, 2014

Image: from a print by Jackie Olenick.

May 15, 2014

Turning five

What do you miss?

asked the interviewer--

-- Luisa A. Igloria, "What do you miss?"

My mother's gathered blue silk

beneath my fingers. Sun hat

sketching a floppy bow. Pearls

heavy as an Olympic medal.

Scratchy gold ribbon twining

my ankles, tethering my shoes.

Not yet knowing why clip-on earrings

wouldn't fool my dad for an instant.

Not yet knowing all the rules

that even God can't break. Certainty

that luncheons and pink lemonade

would last.

In response to What do you miss?

For further reference: Dress-up party.

May 14, 2014

Talking to kids about friends, neighbors, and danger

How do you tell children the story of the friend of God (Abraham) & his neighborliness in an era of "stranger danger", @velveteenrabbi?

— Ayesha Mattu (@Ayesha_Mattu) May 14, 2014

My dear friend Ayesha Mattu tweeted this to me, and my mind started racing. Because on the one hand, I am an incredible admirer of Abraham. I try to take him as a role model. At every Jewish wedding I perform I mention that the chuppah (wedding canopy) is open on all sides, like the tent of Abraham -- a symbol of welcome and openness to the diversity of human experience. I love that Abraham is called the "friend of God," and I love that our tradition teaches he went forth in response to God's call into unknown adventure. I want our son to grow up to emulate Abraham in these ways.

And on the other hand...our son is four-and-a-half. I know that he still inhabits the Eden of believing that everyone in the world is loving and kind and genuinely wants the best for him. Someday I am going to have to teach him that he can't trust everyone, and that breaks my heart -- but that's a heartbreak I infinitely prefer to (God forbid!) the heartbreak of him blithely following someone into harm. How do I navigate that tension?

The Hasidic master known as the Meor Eynayim ("The Light of the Eyes") taught that when Abraham opened his home in hospitality to strangers, he was greeting the face of Shekhinah. In other words: when we open ourselves to those who are different from us, we encounter the presence of God. I believe this deeply, and I aspire to live by its light. After all, the verse most often repeated in Torah the injunction to love the stranger, for we were strangers in the land of Egypt. Being kind to the stranger is central to our tradition.

We've tried to teach our son to be kind to everyone he meets. To treat everyone he meets as a potential friend. To be gracious (okay -- as gracious as a four-year-old can be!) in sharing toys and art supplies and stickers when friends come over. To be open to meeting new people and having new adventures. So far I think it's working. He is one of the most open, sweet, and (age-appropriately) generous kids I know. Once, in an airport, he saw a baby crying and he wanted to give that baby his lovey, because he knew the lovey helped him stop crying when he was sad. I love this about our kid.

And yet I know that not every new person, not every new adventure, is safe.

I remember a few years ago taking our son to the local coffee shop (with which he was already intimately familiar!) and standing at the counter to buy some ground coffee -- and looking down to discover that he was no longer by my side. I panicked and shouted his name. "Oh, he's over there," said the barista, pointing to a table, and I saw our son seated with four perfect strangers, merrily babbling to them as they laughed, clearly enjoying his company. "I figured you knew them...?" I did not know them. Thank God, they were friendly strangers! And in our small college town, that's usually a safe assumption. But that isn't true everywhere.

In the Twitter conversation which arose out of Ayesha's tweet, she mentioned the tension of wanting to keep her son safe and also wanting him to connect with the homeless and with those in need. I know the feeling, though I'm pretty sure our son has never seen a homeless person -- homelessness does exist in our rural county, but not in his orbit. We try to teach him generosity in the small ways that we can (for instance, teaching him that the clothes he's outgrown go to other kids; that toys he's outgrown go to kids who might not have toys of their own) -- but I don't know how he'll respond the first time he sees genuine need. And I hate that we will eventually have to teach him that there are people in the world who seem ordinary but might have hurtful intent.

How can I teach our son to emulate Abraham's openness and hospitality without putting him in danger? Right now his experiences with unfamiliar adults are curated and moderated by we who care for him -- his parents, his grandparents, his schoolteachers. As he gets older, we'll continue teaching him discernment about strangers and safety in different situations. (Here's a good article about how to talk to young children about strangers.) I desperately want to protect him from harm -- and I also don't want him to lose his ability to be open to, to befriend, and to learn from people who may be different from him.

Other parents, teachers, therapists, social workers, anyone reading this who wants to weigh in: how do you balance teaching children about openness to strangers, to the "Other," with age-appropriate awareness of the world and its dangers?

May 13, 2014

The road and the walking

Wanderer, your footsteps are

the road, and nothing more;

wanderer, there is no road,

the road is made by walking.

By walking one makes the road,

and upon glancing behind

one sees the path

that never will be trod again.

Wanderer, there is no road--

only waves upon the sea.

Caminante, son tus huellas

el camino, y nada más;

caminante, no hay camino,

se hace camino al andar.

Al andar se hace camino,

y al volver la vista atrás

se ve la senda

que nunca se ha de volver a pisar.

Caminante, no hay camino,

sino estelas en la mar.

― Antonio Machado, Campos de Castilla (1912), translated by Betty Jean Craige

I encountered this poem in a daily "Making the Omer Count" email from the Jewish Mindfulness Network (sign up here) and it struck a chord. "Wanderer, there is no road / the road is made by walking." I hear the poet saying that although we may imagine that there is a single correct path on which we're "supposed" to walk, that's a fallacy -- a comfortable and perhaps comforting notion, but not ultimately true. There is no single right way to live a life. Do you find comfort in the idea that you're "doing it right" -- or do you castigate yourself with the idea that you're "doing it wrong"? The self-praise and self-blame are equally incorrect. There is no single path. Wherever you are, is wherever you are. You can't be in the wrong place, because by definition, whatever path you're walking is your path.

We may imagine that we know where we're going. We may pretend that we're in control of the journey and we can anticipate both the destination and the turns the road will take along the way -- but that too is a falsehood. No matter what I do or don't do, there are things I can't control. Sickness and health; other people's choices; what hand of cards I will be dealt in any given moment -- all beyond my ken. The only thing I might be able to control is how I respond to what arises in me and around me... and even there, my ability to maintain control isn't absolute. What would it feel like to yield, to let the road unfold as it will and to seek the blessings in wherever the road takes us? What would it feel like to trust that my footsteps are the road, that I am always already where I am meant to be?

"The road is made by walking." This line shifts me from thinking in terms of an individual life, to thinking in terms of community. I think of halakha, the Hebrew word usually translated as "law." Halakha is the ongoing conversation between our texts, our sages, and today's interpreters. Halakha is the process which seeks to connect our actions with the revelation at Sinai and our communal connection with God. And the word halakha comes from the root which connotes walking. In its deepest sense, halakha is not a set of strictures and instructions -- it's a way of walking. My teacher Rabbi Daniel Siegel has taught that halakha doesn't speak; halakhists do. Which is to say: there is no single authoritative voice of the halakha. Instead we have the many and varied voices of those who strive to interpret what has come before us. We make the road by walking.

"By walking one makes the road[.]" Each of us walks her own path. Only in looking back may we achieve full clarity on where we've been and how we got to where we are -- and that hindsight comes with the price of not being able to walk any stretch of the road twice. I think of all of the milestones I've passed along the way, and I know that the road of my life will never return to those places. Not only that, but the minute during which I began to write this post...? Gone, and unrecoverable. The minute during which you began to read...? The same. The only path we can see clearly is the one we've already walked, and because we've already walked it, it's fixed. The road ahead is limitless potential, an infinity of choices and changes. Only the road behind can be known. Every step I take builds the road of my life beneath my feet.

And after all this, Machado takes the poem's ultimate turn: in truth there is no road, only waves on the sea. Life is flux and change, the ratzo v'shov ("running and returning") of Ezekiel's angels and of our own spiritual lives, the waves going out and the waves coming in. That, in turn, reminds me of one of my favorite parables which I first heard at Elat Chayyim from Rabbi Jeff Roth -- the two waves in the middle of the ocean, one big and one small, and the big wave was weeping with fear. "Why are you crying?" asked the little wave. "If you could see what I see," said the big wave, "you'd cry too -- we're headed for a rocky shore, and when we reach the rocks, we'll be shattered into nothingness!" But the little wave had access to a deeper wisdom, and said to the big wave, "we're not waves -- we're water."

We're not waves, we're water. We are more than individual souls who shatter on the rocky shoals of death. That within us which is eternal remains eternal, even when the form we've taken during this life comes to its end. An individual wave disperses into foam, but the motion of the sea is forever. And so are we. My path, your path, the footsteps of everyone who has ever lived and everyone who will ever live -- waves which come and go, run and return. Life, being, the very cosmos -- expanding and contracting, inhaling and exhaling, beginning and ending, beginning again.

May 9, 2014

Announcing April Dailies

One of my readers asked me recently, "Are you going to publish your National Poetry Writing Month poems? Because otherwise, we're going to have to resort to just printing them out." My mother said the same thing to me last year. In both cases, I promised that I could improve upon a sheaf of print-outs.

One of my readers asked me recently, "Are you going to publish your National Poetry Writing Month poems? Because otherwise, we're going to have to resort to just printing them out." My mother said the same thing to me last year. In both cases, I promised that I could improve upon a sheaf of print-outs.

On that note, I'm delighted to be posting today to announce a new chapbook -- April Dailies! Here's the official description:

Writing daily poems is a discpline designed to prime the pump of creativity and to hone attention to the ideas, phrases, and everyday miracles which are a part of every life.

This chapbook collects the results of an annual month-long experiment in attention: daily poems written during the spring of 2013 and 2014, now revised for publication.

(It also replaces the chapbook I put out last year, which contained last year's daily poems plus the commentaries I'd posted alongside them -- that one's now officially out of print.)

Here are this year's poems, arising out of recent travels in Jerusalem and Hebron, Pesach and the journey into the Omer, small-town country life -- and last year's poems, arising out of parenthood, brushes with sorow, and spring.

Many of the poems have been substantially revised from the original versions posted here during NaPoWriMo.

I love the discipline of writing daily poems, especially in the context of a community of others who are engaging in the same practice. It's a lot like writing weekly poems, a practice which I've had off and on for years. (See 70 faces and Waiting to Unfold, both published by Phoenicia.)

Whether writing daily or weekly, the process mimics my former life in small-town journalism. The relentless constancy of regular practice mitigates against perfectionism, and that in turn lets me access a different kind of creativity.

Writing daily poems keeps me attentive to the poetic possibilities of ordinary life, just as daily prayer practice keeps me attuned to living with prayerful consciousness. I hope that reading them brings some joy to you.

Available at for $5.70 at Amazon.com, and for £3.50 at Amazon.co.uk and €4.00 at Amazon Europe.

May 7, 2014

Be kind

A while back, one of my friends posted something on Facebook which resonated with me -- a quote which suggested that we never know when someone is facing something difficult or painful, or carrying some hidden grief, and so the most important thing is to be kind.

A while back, one of my friends posted something on Facebook which resonated with me -- a quote which suggested that we never know when someone is facing something difficult or painful, or carrying some hidden grief, and so the most important thing is to be kind.

When I did a google search, trying to find the quotation in question, I found "Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle," sometimes attributed to Plato, sometimes Philo, and other times to John Watson -- not the Arthur Conan Doyle character, but the reverend. (For more on this: Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a battle - quoteinvestigator.com.)

I've seen a variation on this idea raised in response to various online imbroglios. If someone doesn't reply to your comment right away, don't assume that they're ignoring you; if someone posts something distressing, try to give them the benefit of the doubt; you never know what's going on in their life behind the privacy of the computer screen.

But even in person, I think it holds true. We never really know all of what's arising in someone's head and heart, or what anxiety or sadness they may be carrying. A fear, a difficult diagnosis, distance from a loved one, regret... we hold a lot of things in our hearts, and many of them are not easy to sit with.

In such a situation as this -- and this is the situation in which we all live, whether or not it's particularly acute at any given moment -- what could be more important than being kind?

One of the commentors on that quoteinvestigator post noted that this is very like a teaching from Mahayana Buddhism. To wit: suffering is pervasive; we compound our suffering by forgetting that we are interconnected; the way out is to recognize our interconnectedness and to treat everyone with kindness.

In my religious tradition we say that chesed, lovingkindness, is one of the fundamental characteristics of God -- and as we are made in the divine image and likeness, lovingkindness is an essential human quality, too. "On three things the world rests," says one of our aphorisms: "on Torah, and on avodah (service / prayer), and on gemilut chasadim (acts of lovingkindness)." Without acts of lovingkindness, the world would not endure.

It's not always easy to respond to the world from a place of chesed. I am reminded of this daily in a hundred tiny ways. Our child dawdles getting dressed and I risk being late to meet someone. Someone sends an email which agitates me and makes me angry. I hear something on the news which raises my ire. I don't always manage to respond in the way I might wish.

But it's a goal worth aiming for. Because we all suffer, and we all carry wounds both old and recent, and we all yearn to be met with kindness.

May 6, 2014

Poems of miscarriage and healing

After reading Rabbi Robyn Fryer Bodzin's poignant and courageous essay Can We Please Tone Down Mother's Day This Year?, about facing Mother's Day after repeated miscarriage, I wanted to post here to offer a reminder of a small resource which is free to share: my chapbook Through, poems of miscarriage and healing, published in 2009.

Through is available for free as a digital download, or printed at cost (under $5) if you want a paper copy for yourself or for a loved one.

Here's what others have said about the collection:

"This can't have been an easy experience to write anything about at all, let alone to distill into ten brief, searing, and luminous poems. As with Rachel's earlier chaplainbook, these are accessible poems with several different layers of meaning, so I think almost anyone who's ever gone through a miscarriage will get something out of it. Which is not to say the audience should end there: miscarriage is a subject every bit as relevant and revealing of the human condition as warfare, for example. So why doesn't it get more attention from writers and artists?" -- Dave Bonta, at Via Negativa

"The Velveteen Rabbi, Rachel Barenblat, has written a collection of poems about miscarriage -- based on her own -- and offers Through to any reader who wants or needs them. As Dave Bonta points out, miscarriage is not a widely discussed topic, certainly not by men too often, but not even by women. Find comfort and companionship in shared grief and experience. For yourself, or someone you know." -- Deb Scott, at ReadWritePoem

Miscarriage, and sorrow around infertility and attempts to conceive, are among the silent scourges we usually endure alone. But I believe there can be some small comfort in sharing our stories and in knowing that others have walked -- continue to walk -- these difficult paths.

You can read excerpts from the collection, and/or click through to the free download or the at-cost printed edition, at the original post announcing the chapbook's publication: Miscarriage poems: "Through."

May comfort come to all who mourn.

Another poem of hope

NOT THERE YET

When Moshiach comes

everyone will celebrate

interdependence day.

We'll line the streets

for a parade of children

leading lion cubs and lambs,

wave flags emblazoned

with our blue-green earth

against the star-spangled void.

All the world's marching bands

with their gleaming epaulettes

will play anthems in counterpoint.

On that day we'll remember

that every molecule on earth

is made of the same stardust.

All humanity is responsible

for one another. The trees

breathe out what we breathe in.

The only way

to get it together

is together.

The idea that every molecule on earth is made of stardust comes from a recent episode of the show Cosmos, hosted by Neil DeGrasse Tyson.

"All humanity is responsible / for one another" is a riff on the Talmudic phrase Kol yisrael arevim zeh bazeh, "All Israel is/are responsible for one another."

"The only way to get it together is together" is a quote from Reb Zalman.

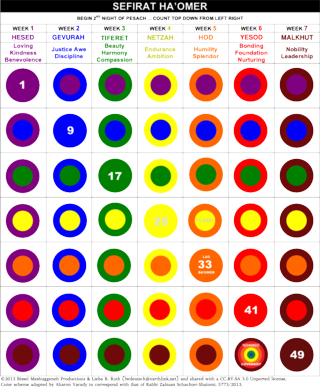

Entering Week Four of the Omer

I haven't been blogging the counting of the Omer this year. I wish I had been able to commit to a practice of writing something inspired by the themes and teachings of each of the 49 days, but there was just no way -- it was either daily poems during April, or daily posts during the Omer, but I couldn't see how to do both! (Maybe some year I'll try writing a cycle of 49 poems during the Omer count, but this was not the year for it.) But I've been thinking a lot about the Omer journey this year.

I haven't been blogging the counting of the Omer this year. I wish I had been able to commit to a practice of writing something inspired by the themes and teachings of each of the 49 days, but there was just no way -- it was either daily poems during April, or daily posts during the Omer, but I couldn't see how to do both! (Maybe some year I'll try writing a cycle of 49 poems during the Omer count, but this was not the year for it.) But I've been thinking a lot about the Omer journey this year.

Today is the 21st day of the Omer -- in the kabbalistic system, the day of Malchut she'b'Tiferet. Malchut means sovereignty, nobility; it evokes the presence of Shekhinah, the immanent divine Presence dwelling within creation. Tiferet means harmony, balance, compassion. In his Omer guide, Rabbi Rami Shapiro describes today's quality as "the capacity to help others without demeaning them." The ability to respond with harmony and compassion from a place of gentle presence and connection with God.

Tonight at sundown we'll enter into the fourth week of the Omer. This is the middle week of the seven: three weeks before, three weeks after. This week is the hinge between the first half and the second half.

In the kabbalistic system, this is the week of Netzach, endurance. (Here's the post I wrote about this week a few years ago: Seeking endurance.) About this quality, Rabbi Min Kantrowitz writes:

Netzach is like spiritual fuel... Helping us get through difficult times with grace, Netzach is available during the bumpy events of ordinary times and the dramatic and unavoidable traumas of life.

Also in that kabbalistic system, the first day of each week of the Omer is the week of Chesed, lovingkindness -- so the day which will begin tonight at sundown will be the day of Chesed she'b'Netzach, Lovingkindness Within Endurance. Rabbi Min writes:

Chesed she'b'Netzach is the fuel that keeps a parent awake for hours in the middle of the night soothing a colicky infant, sustains the exhausted caregiver helping his dying lover, and supports the underpaid teacher of distracted and energetic adolescents.

Perhaps these descriptions will resonate with some of you, as they resonate with me.

Any substantive journey of transformation -- be it counting the Omer, preparing for the Days of Awe, studying for years toward rabbinic ordination, or parenthood -- requires endurance. There comes a time when one has traveled such a distance that the old shores of one's former life have receded in the distance, but the new shores of who one is becoming are not yet visible on the far side of the sea.

The 22nd day of the Omer, which begins tonight, invites us to cultivate lovingkindness as we seek to draw on our own endurance. This is not about gritting our teeth and getting through it. This is a process of responding to whatever arises, as we seek to continue doing the work, with kindness and with love.

How can you be kind to yourself as you try to sustain the big work of your life? How can you hold yourself with love even as you struggle to keep putting one foot in front of the other, despite obstacles and difficulties which inevitably arise? Can you respond even to those difficulties from a place of unending love?

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers