Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 158

May 5, 2014

Crossing Qalandiya: letters between two women

You have no idea how strange I feel lately - almost as if I've started seeing things differently -- through your eyes. Maybe this is normal, because we know each other relatively well now, and of course this has an effect. I keep finding myself explaining 'your side' to people. And, frankly, I am shocked at some of the reactions I get.

There are many people here who are completely blind to the way things look from your point-of-view, and to what your people are going through. I am sure this is also true for some of the people on your side. But suddenly it has become clear to me that so many of the problems are the result of miscommunication and misunderstandings... so the only solution is dialogue.

That's from one of Daniela Norris' letters to Shireen Anabtawi, as collected in Crossing Qalandiya: Exchanges Across the Israeli/Palestinian Divide, published by Reportage Press in 2010. But I'm getting ahead of myself. The book begins with a letter from Daniela, and here are her first words:

That's from one of Daniela Norris' letters to Shireen Anabtawi, as collected in Crossing Qalandiya: Exchanges Across the Israeli/Palestinian Divide, published by Reportage Press in 2010. But I'm getting ahead of myself. The book begins with a letter from Daniela, and here are her first words:

Dear Shireen, I hope you are well, and that you remember me. We met in Geneva last month, at a cocktail party, at Michelle's house. I admit that I was taken aback when you said you were from Palestine. I was convinced you were Italian or Greek -- something Mediterranean, anyway -- but I didn't imagine you were Palestinian.

It is strange, but despite the few kilometres that set us apart, I have never really gotten to know a Palestinian woman. Certainly not one as charming as you. What can I say? I am embarrassed to admit that the image I had of Palestinians was somewhat different...

I have a confession: I hesitated before I went to meet you the next morning. After all, you are supposed to be "The Enemy," and who knows what The Enemy has in store for them? But we said we'd bring our kids along, and when I arrived with my two little boys and saw you waiting at the café with your two beautiful children, I was ashamed of my previous thoughts... Ever since I met you, I read and listen to the news from our region differently, with more compassion for the other side -- your side.

Shireen, in turn, writes back:

Dear Daniela... I appreciate your frankness. I must admit that the only Israelis I've met over the past years have been the soldiers at road-blocks, and I, too, found it strange to meet an Israeli woman with whom I was able to connect so easily....

You ask about my daily life in Ramallah. I hope that one day you'll be able to visit me here. Ramallah is beautiful. When I was in Europe and said I was from Ramallah, people asked me whether we had roads, shops, food. I was surprised to hear these questions. It's so sad that this is the image we have in the eyes of the world.

...All in all, my life here is pretty good, but I must admit that it is difficult to come back to Ramallah after spending time in Europe. When we travelled, we drove from country to country and were rarely asked to show a passport. Here, if I want to visit my family in Nablus, I have to show documentation and permits; not only that, but I have to wait long hours at road-blocks, in the heat or in the rain...

Daniela and Shireen met by chance at a party in Geneva. Daniela had worked for the Israeli Foreign Service for seven years, and later was an advisor to the Permanent Mission of Israel at the UN in Geneva. Shireen is a former director of Public Relations at the Palestinian Investment Agency in Ramallah, and later worked for the Palestinian Permanent Mission to the UN in Geneva. As the book's introduction explains, the two women met many times in Geneva over several months, with and without family members, and their friendship bloomed. Neither speaks the other's language, so their communication was in English, the language which they shared.

Once they returned home again, despite the geographical proximity of their homes, they were worlds apart. So this correspondence began. Each wrote in her native language, and then translated it into English before sending. The end result is this book, which I bought at the Educational Bookshop in Jerusalem last month and have only now finished reading.

Because this is a collection of correspondence, it's difficult to offer representative excerpts. Their conversation loops and circles, and subjects recur frequently. Sometimes a letter will be held up inexplicably and will arrive weeks after it was sent. Sometimes one woman's letter will veer off onto a tangent, and at the end she will apologize for not responding to the questions asked last time, and will promise to get to them in future correspondence. The narrative is disjointed and messy, much like life.

In one letter which I found particularly memorable, Shireen tells the story of her wedding day. The Israeli army had imposed a curfew that day, which meant she couldn't travel on the road to Ramallah where her husband-to-be and his family were waiting. Instead she had to hire a man with a donkey to carry her over the hills in her wedding dress. In the end, the evening was transformed from one of anger and frustration to one of surprising beauty. In another, Daniela talks about the Jewish custom of circumcising baby boys (which, to her surprise, Shireen confirms that Muslims do, too) and about how difficult she finds the whole thing, and how she and her husband chose a hospital circumcision and a party at home afterwards instead of doing things the traditional (religious) way.

As the mother of a small child myself, I am consistently moved by the way these women write to each other about children -- their own kids, and each others' kids, and their wishes that their kids could meet in the land(s) where they live and could grow up as friends. Daniela and Shireen talk about the responsibilities of motherhood and whether or not their husbands do the dishes; they compare notes about playgrounds and kindergarten and what to do with kids during the long school-free summer. But the parenthood conversation always leads seamlessly into the bigger political conversation. Motherhood and the difficult realities of Israeli-Palestinian tension are inextricably intertwined.

In one letter, Daniela expresses sorrow that Shireen's children are afraid of Israeli soldiers, and don't have a good playground nearby as hers do -- and then expresses her anger that her own children are afraid of suicide bombings, and asks why Palestinian textbooks teach their children to hate Jews. Shireen writes back to say that she is quite startled by that question; she explains that their textbooks contain no such things, and that an independent European Union commission has looked into this and can affirm that it is true. "The only thing that makes our children hate Israelis is the occupation," Shireen writes, "and you Israelis have got the power to change that."

It's clear, reading these letters, that both women are making a concerted effort not to demonize each other or to accuse each other. It's also clear that this correspondence isn't always easy, and that each woman has the uncomfortable experience of bumping up against someone else's truth, someone else's narrative, which flies in the face of the way she was taught to think about both "us" and "them." And yet they keep writing, because their friendship has come to be important to them. They talk about holiday practices and foods: Shireen describes Ramadan, Daniela describes Pesach and the Days of Awe. They talk about their hopes for their kids and the world they want their kids to inherit.

In one letter, late in the book, Shireen writes:

You asked me in one of your last letters why we commemorate the nakbah, our disaster, when we were chased away from our lands and the state of Israel was founded. I haven't answered the question, because it is very difficult for me to see that you cannot really see the reason. How can we be happy for you Israelis, rejoice that you have your own state, when we do not have our own?

Daniela's response begins:

Your last letter was extremely interesting for me to read. I can't say I knew all those things about Palestinians living in other countries, or about your nakbah. When you explain, I have to admit that they suddenly make some sense. I am glad you shared your point of view with me, because it is the first time I have come close to really understanding these things.

As an American reader, I'm fascinated by the blind spots, the things each woman doesn't know about the other's life or experiences. It's particularly poignant because they do live so near each other, and because they have so many things in common. Maybe what makes their correspondence (and their friendship) work is the fact that they're not trying to convince each other of anything. They're doing the hard work of sitting with the tension. As my friend and teacher Rabbi Brad Hirschfield put it in the title of his memoir, "You don't have to be wrong for me to be right."

I'm going to share one more quote from the book -- an extended quote from a letter written by Daniela toward the end of this correspondence. (The book ends with their letters promising to try to meet at the Qalandiya checkpoint; we don't find out whether they made it, or what that in-person encounter was like, or what has transpired since then.) This passage has stayed with me because it's such a cogent description of the interior process of broadening one's perspective:

I have found myself going through a process over the past few months, a sort of understanding that took me from believing that 'everything is your fault' through 'perhaps it is a little bit our fault, too' all the way to the conclusion that we actually share the blame -- equally. Without undermining your responsibility for the situation, I would like to be able to be honest enough with myself and with you and to address our own responsibility, which definitely exists.

It is true that it is perhaps easier to be in a position of power, but I really think that this position of power is now ruining us. It separates my people and causes our morals to decline. We always took pride in being a moral people. You may laugh, but I believed in it, too, until very recently. But we are raising generations of children, youths and adults who develop the mentality of 'occupiers'...

I hope that later this year we will be able to sit together, in Tel Aviv or in Ramallah, and have coffee again and watch our children play -- without fearing each other. How do you say in Arabic -- inshallah?

This isn't a book which offers answers to the big systemic questions of violence and power, or to the reality of two traumatized peoples who remain at odds. But it does offer a glimpse of how two women can forge a friendship not by ignoring what divides them, but by speaking frankly about it, and by being open to hearing difficult things which contradict their usual way of understanding the world. I think that's pretty rare, and I admire Daniela and Shireen greatly for it.

Partial proceeds from sales of the book go to Children of Peace, a British nonprofit organization which works with Israeli and Palestinian children. Buy it at Amazon.com or at The Strand or wherever you usually look for books.

This week's portion: creating liberation; Shavuot; and the Jubilee

This week's Torah portion, Behar, tells us that when we enter into the land we may farm for six years but the seventh year should be a Shabbat for the land. During that year we should neither sow nor reap; it is a chance for the earth to experience the sacred rest which is part of the structure of creation. The Torah goes further: not only is every seventh year meant to be a shmita (sabbatical) year, but after seven "sevens" of years -- 49 years -- the 50th year is the Yovel, or "Jubilee," and that year too is a year of sacred rest.

This week's Torah portion, Behar, tells us that when we enter into the land we may farm for six years but the seventh year should be a Shabbat for the land. During that year we should neither sow nor reap; it is a chance for the earth to experience the sacred rest which is part of the structure of creation. The Torah goes further: not only is every seventh year meant to be a shmita (sabbatical) year, but after seven "sevens" of years -- 49 years -- the 50th year is the Yovel, or "Jubilee," and that year too is a year of sacred rest.

During the Yovel, all debts are cancelled; those who have gone into indentured servitude are released; and any land transactions which have taken place are annulled so that the land can return to its original owners. Or perhaps I should say, original caretakers -- since Torah is clear that the land may be lent to the tribes of Israel, on condition of appropriate behavior thereupon, but it truly belongs to the Holy One of Blessing.

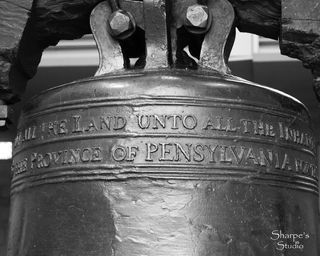

It's always striking to read these verses during the counting of the Omer. This week's Torah portion instructs us to count seven "sevens" of years, and to celebrate the 50th year as a time for proclaiming liberty throughout the land. Right now we are counting seven "sevens" of days, and we will celebrate the 50th day as the time of the giving of the Torah. What might the parallel teach us? How is Shavuot like the Jubilee?

In his collection Tales of the Hasidim, Martin Buber recounts that the rabbi of Kotzk was asked: "Why is Shavuot called 'the time the Torah was given' rather than the time we received the Torah?" The Kotzker answered: "The giving took place on one day, but the receiving takes place at all times." Shavuot is the day when we celebrate God's gift of Torah -- but the reciprocal process of actively receiving Torah is ongoing. The Jubilee year is the year when we celebrate release from our accumulated debts and transactions -- but the reciprocal process of actively creating liberation is ongoing.

The sabbatical and Jubilee year teach the importance of emunah, trust and faith. In the ancient world, taking a year off from cultivating food was a profound gesture of emunah. It required a leap of faith in God Who would provide even if we stopped our farming and harvesting. (And if that were true of the sabbatical year, how much more so the Jubilee year.)

My b'nei mitzvah students frequently ask me whether this ever actually happened. Maybe, maybe not. I can offer a variety of rabbinic teachings about the conditions under which we are traditionally considered obligated to follow these teachings. But for me, that's not the interesting question. I'd rather ask: what spiritual truths can we learn from this week's Torah portion?

As Shabbat is our weekly reminder to relinquish work and to recognize ourselves as holy and beloved regardless of our job titles, salaries, or accomplishments, the shmita year reminds us that the earth too is holy and beloved regardless of how "valuable" it may be and regardless of how we may usually put it to work for us. And the Yovel year urges us to let go of debts and grudges, to relinquish old angers and outdated paradigms, in order to experience true freedom.

It's only when we are free that we can choose to enter into a different kind of relationship -- the covenant between us and God which we reconsecrate and renew at Shavuot. Slaves to Pharaoh, slaves to overwork, slaves to opinion and custom can't enter into real relationship with God. But once we are free, then we can choose: not to be enslaved, but to serve. Our purpose in this life is not earning money or seeking fame. It's serving God through caring for our planet and living in right relationship with each other.

This requires emunah, trust and faith, no less than the temporary cessation of farming did. To proclaim release and liberty -- to consciously free ourselves from old paradigms, constricted understandings, the grudges and hatreds we have taken on -- requires us to trust that something better is possible. It requires us to believe that there is more to who we are than our accumulated labels. But imagine if each of us could really do that. What new Torah might we be capable of receiving at Shavuot then?

Image: closeup of the Liberty Bell, with its inscription of a verse from this week's Torah portion: "Proclaim liberty throughout the land unto all the inhabitants thereof."

Nice mentions

A quick shout-out to a few places where my work has been cited or linked lately:

First -- over the weekend, Rabbi Amy Ehrlich quoted my commentary on last week's Torah portion, Emor, in her at sermon at Temple Emanu-El in New York! Temple Emanu-El was the first Reform Jewish congregation in New York City; Rabbi Google informs me that it's the largest synagogue in the world, and that because of its size and prominence, has served as a flagship congregation in Reform Judaism since its founding in 1845. You can hear her sermon on their worship broadcast page, and if you're curious to read more of the d'var Torah which she cited, it's here: The bodies we are.

Secondly, at Linguae Antiquitatum there's the first edition of an Ancient Languages blog carnival, and the carnival curator asked for permission to link to a few of my old posts. There's an excerpt there from the 2008 post where I offered a translation of the first few lines of the Qur'an into Hebrew, along with some thoughts about poetry and translation; also a quote from a post about the Arabic words nafs and ruh and their similarities to the Hebrew nefesh and ruach. It's neat to see interest in those posts six years after they were written.

Thanks, y'all!

May 4, 2014

The inner lives of Arab and Jewish Peacemakers

I live in two universes when I work in the Middle East. One is a universe where peoples are divided by bitter and violent sorrows, old resentments, understandable suspicions, and completely polarized affiliations. It is a world of great injustices and passed-on abuse, a place where people wait for apologies but are unable to offer any.

Within that world, however, there is another world, a secret world of those people who dare touch those of the other side with their words, their deeds, and their hearts. That special world is to me -- as an activist, spiritual seeker, and analyst of conflict -- a universe of enormous significance. For it is in that mysterious world of human bridges between enemies that we find flowering up from a ground of death, hatred, and war, something extraordinary: the seeds of life, the seeds of the future.

So writes Marc Gopin in the introduction to Bridges Across An Impossible Divide: The Inner Lives of Arab and Jewish Peacemakers.

I have been working my way through this book slowly. The writing is clear, but the stories the peacemakers tell are intense and they merit close attention. Here's another quote from Gopin, responding to the beginning of the story told by peacemaker Ibtisam Mahameed. Ibtisam has mentioned the battle in Tantura in 1948; in the standard Palestinian narrative, this battle was a horrific massacre of Palestinians by Israelis. In the standard Israeli narrative, though the fact of a battle is uncontested, there is no massacre. Gopin writes:

I have become used to hearing these stories from the many Palestinians who I have come to know over the years. So many stories, and they seem to add up to a pattern of abuse in 1948 that continues to shock me. Each time it sends me into a tailspin, and I am still trying to examine my own reaction. Is it shame? I was brought up to believe that Jews were incapable of acting this way.

Gopin's description of the tailspin engendered by hearing these kinds of stories is familiar to me. I don't want to devolve into endless navel-gazing about how my Jewish soul aches both when Jews are victimized and when Jews victimize others -- but I think that confronting my own feelings can help me do the important spiritual work of living with the both/and where the Middle East is concerned.

Ultimately, he concludes, for the purposes of this book it does not matter whether 250 people were killed extrajudicially in Tantura or fifty. What matters is that it was a horrifying night for civilians, who (everyone agrees) were expelled from their homes and imprisoned just after the battle, and that there were deaths, and that this memory continues to haunt those who were there and the descendants of those who were there. What matters, on a personal scale, is the trauma which continues to be carried. (On every side.)

In her interview, Ibtisam moves from the trauma of memory to a philosophy which argues that war and violence are the easy path, and that peace is the hard courageous work:

I don't want to leave anger and sadness in my heart. First of all this will affect my health, and I felt that dialogue and discussion with the other side, even if you feel a strong pain inside, is better than throwing a rock at them. I want to give peace as a legacy to my children and grandchildren.

Ibtisam articulates a feminism which is rooted in her sense of the God-given equality of men and women. And she also argues for the importance of having women as peacemakers and bridge-builders:

I believe that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict started long ago, not from the 1948 war, it started since Ibrahim's era when he decided to marry Hagar, who gave birth to Ishmael. Then Sarah gave birth to Isaac, and then both of those women have a conflict over one man, Ibrahim. Therefore Ibrahim had to take Hagar with her breast-feeding baby to a distant mountain which was deserted. He left her there and return back to Sarah. Therefore the brothers were raised separately and didn't have any kin relationship...

I believe that at the end, there will be a solution to this conflict, and there will be peace in the Middle East. But the role of women in this conflict is harder than that of men, because women are those who hold their child inside. And they are the ones who are responsible to raise him. So, if a mother loses her child, she will hold a severe pain in her heart. That's why we as women have to be more aware to the political movement, and become part of it.

Here's an excerpt of an interview with Ibtisam. This is part of an interview series called "Unusual Pairs," also a Marc Gopin project (with filmmaker David Vyorst) -- I believe the videos came first and the book grew out of the video interviews.

(If you can't see the embedded video, you can go to it at YouTube: Elana and Ibtisam.)

Parallel to the chapter which tells Ibtisam's story is a chapter which tells Eliyahu McLean's story. Eliyahu was the leader of the Jewish half of the Dual Narratives Tour of Hebron which I did earlier this spring. He recounts how he first fell in love with Israel, and how his Zionist activism in Berkeley, California, offered him the opportunity to go beyond his comfort zone and hear a different story:

[W]hen I first came to Berkeley, there was an initiative to make Berkeley a sister city with Jabaliya Refugee Camp in Gaza... I was opposed to the initiative at the time. I started to meet the Yes on Jabaliya [group], and for the first time I started to learn the narrative of the other side of the story, the Palestinian people.

I became so curious to learn about the "enemy" that I started to study Arabic, Islam, Middle Eastern Studies... [Later] I was at Hebrew University in Jerusalem and I met the dean of students at Bethlehem University. I met a young student at Bethlehem University from Deheishe Refugee Camp and I became friends with him. So then I started to bring students from California to Bethlehem, Bethlehem University, and the refugee camp; that was the beginning of my bridge building work.

I'm particularly moved by Eliyahu's story about how, influenced by Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach and Jewish mysticism, Eliyahu goes to Cairo and meets a West African Sufi who becomes, in his words, his hevruta -- his spiritual study partner. As Gopin notes, "This is cognitive dissonance for a traditional Jewish audience; it is a psychic and epistemic reframing of the nature of the Jewish spiritual universe." Eliyahu adds:

I think that friendship and building friendships is a very important aspect for peacemaking... I hear a lot of left-wing Israeli activists, or people in the mainstream, saying we don't have to love the Palestinians. We just have to come to a pragmatic agreement, separate the two sides, give them what they want, take what we want. But I believe that that is not enough... My work is about building a deep, deep connection and friendship and partnerships with Palestinian Muslim Arabs, Christians, Druze.

Eliyahu also talks about how -- as Gopin puts it -- "most people cannot cope with staying truly in-between, as a connector between enemy groups. But he feels that this is the essential task that is necessary for a different future."

There is a dynamic, sometimes, when Israelis form friendships with Palestinians. They feel so guilty and shameful about what Israelis are doing to the Palestinians at check points, the Occupation, all of these things, they feel resentful towards their own community, and they feel like they have to over-identify.... And I believe that I can understand that motivation and it's very honorable that they feel so much compassion for the other.

But I feel that to make a shift in an Israeli-Jewish public and society, it is important for me to be grounded within my own close circle of friends on the israeli side and also on the religious Jewish side... In order to make an impact I have to stay and keep wearing my payos and keep wearing my tzitzit and stay as someone who is fully connected to that community... [And years later someone in that community might think,] We want to connect as human beings, but we have so many walls of fear, walls of fear between us and the other. But our friend Eliyahu has broken through that wall, so maybe he can be an example for us.

Eliyahu also tells an amazing story about going to a shiva (paying a visit on a mourner) for a friend of his who had been killed by a suicide bomber, and how he felt awkward saying to the bereaved father in that setting that his work was in the field of peace and dialogue with Arabs and Palestinians. And then a year later he was at the unveiling of his friend's tombstone, and the bereaved father said "I am counting on you" -- "In other words, keep doing what you are doing."

Here's video of Eliyahu talking about these issues and this work, alongisde Sheikh Bukhari -- another "Unsual Pair."

(If you can't see the embedded video, it's here: Eliyahu McLean and Sheikh Bukhari.)

The latter half of the book contains in-depth quotations from peacemakers in their own words. "The entire project of Unusual Pairs, both the film project and this written study, were designed by me with a working assuption tha a true understanding of the mysterious way in which love and friendship reaches across the boundaries of enemies can only be understood through a direct exposure to the peacemakers themselves, through film and through their words," writes Gopin.

Most American Jews don't know, or meet, or hear from peacemakers who are doing this courageous, difficult, incredibly important work. If you care about the Middle East, or about peacemaking writ large, this book is well worth your time.

May 3, 2014

Motherhood poems for Mother's Day

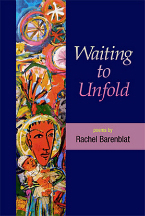

Looking for a Mother's Day gift for someone in your life? Allow me to suggest Waiting to Unfold, published by Phoenicia last year. Here's how the publisher describes the collection:

Poet and rabbi Rachel Barenblat wrote one poem during each week of her son's first year of life, chronicling the wonder and the delight along with the pain of learning to nurse, the exhaustion of sleep deprivation, and the dark descent into -- and eventual ascent out of -- postpartum depression.

Barenblat brings her rabbinic training and deep spirituality to bear on this quintessential human experience. She also resists sentimentality or rosy soft-focus. While some of these are poems of wonder, others were written in the trenches.

These poems resist and refute the notion that anyone who doesn't savor every instant of exalted motherhood deserves stigma and shame. And they uncover the sweetness folded in with the bitter.

By turns serious and funny, aching and transcendent, these poems take an unflinching look at one woman's experience of becoming a mother.

If you live in western Massachusetts and would like for me to inscribe a copy for someone, just let me know -- I am happy to sell you a signed copy in person (or, I suppose, if you live elsewhere and ask for this quickly, I could sign one and send it to you in the mail in time for the holiday.)

Waiting to Unfold costs $13.95 (US, CAN) / £9.10 / €10.66 and is available at Phoenicia Publishing and on Amazon (and Amazon UK and Amazon Europe) -- though publisher and author earn more if you buy it directly from Phoenicia. Still: buy it wherever works for you. Enjoy!

May 2, 2014

Thank you, God, for the flowers on the trees

Our son has been really excited about the slow unfolding of spring. Never mind that it's been in the forties and raining. Ever the optimist, he asks every morning if today's the day he can wear short sleeves. He literally jumps for joy at the sight of daffodils. And today we glimpsed the year's first blooming tree.

Our son has been really excited about the slow unfolding of spring. Never mind that it's been in the forties and raining. Ever the optimist, he asks every morning if today's the day he can wear short sleeves. He literally jumps for joy at the sight of daffodils. And today we glimpsed the year's first blooming tree.

"Look," I said, pointing out the car window, "that tree's starting to bloom!"

"What does bloom mean?" he asked.

"Bloom means flower," I told him. "That tree is going to have flowers." I spotted another one. "And that one, too!"

"Wow! I didn't know that! I thought flowers grow on the ground."

"They do," I agreed, "and also, some kinds of trees have flowers in the spring. Actually, there's a special blessing to say when you first see trees blooming," I told him. "Baruch atah Adonai, eloheinu melech ha'olam --"

And then I faltered. I haven't said the blessing over blooming trees since last spring; I couldn't remember exactly how it went. "And then you thank God for making the beautiful trees and their flowers and everything in the world," I concluded.

"I can't say all of that," he told me primly. I guess even in English, that's a mouthful.

"You could just say thank you for the trees and their flowers," I suggested.

"Thank you God for the flowers on the trees!" he crowed, satisfied. And then he had an idea. "When it's Friday night we could say 'Shabbat shalom, trees!'"

"We could," I agreed. Thank You, God, for this kid, I thought, as we drove on.

(You can find the blessing for blooming trees, along with some commentary, here: The Annual Blessing Over Trees.)

April 30, 2014

Daily April poem: a poem of beginnings and endings

TRANSITION

In through the double glass doors

with secondhand bathrobe in hand.

I leave sovereignty in the trunk.

I don't know what I'm losing

can't imagine new stars in the sky.

Once I start saying I can't

sure hands thread my spine.

I gaze at foam ceiling tiles.

Through the window: parking garage,

dark conifers, distant hills.

I climb the ladder to the room

above the clouds, the one

with a new incarnation inside.

Close my eyes and let go.

Luisa A. Igloria offered this prompt for today:

Every beginning, every end, has something of both the sweet and the not-sweet. Let me taste both, in a poem of beginnings and endings, endings and beginnings. Let it have doors and windows, ceilings, roofs, ladders, and stairs. Let it also have mountains and trees, the sweep of open spaces.

I did my best to comply. (I'm also delighted to see that she's posted a roundup of all of her NaPoWriMo prompts -- I mostly worked with #blogElul or NaPoWriMo prompts, so most of hers are new to me, and I hope to use them in coming weeks and months!)

Happy National Poetry Month to all!

April 29, 2014

Daily April poem: twenty little poetry projects

EVENING IN THE OLD CITY

At sunset the city walls are on fire.

No one whose eyes take in that pink stone

will ever be the same. Pomegranate juice,

tart, stains the cobbled streets.

Cheap cigarettes and sweet smoking coals

duel for ascendance. The man dressed

like an eighteenth-century disciple

walks fast, his head down. Teenagers

call out in their incomprehensible dialect.

A man pushes a cart piled with breads

round loops encrusted with seeds and zataar

and a little boy tastes them with his eyes.

Abraham, God's beloved, would balk like a mule

if he walked these streets now. Cars

scraping through the narrow alleys

of the Old City, neon signs and loud music

just outside Damascus Gate. No:

Abraham would feel right at home here.

He'd raise an eyebrow at the motorcycles

but the press of shoppers demanding

fresh mint, dates, eggplants would feel

just like home. "Okay yalla bye," says

the girl with the blue rhinestone cellphone,

pushing past in the other direction.

Because this is a holy city, anyone

who hears God's voice here is right.

The soothing whisper of tradition...

Overhead, bright flags remind passers-by

how little we have in common. Abraham

climbs to the top of the mount, walks

quiet circles around the rock

where he almost made the worst mistake.

(Velveteen imagines this from her desk

overlooking still-bare Massachusetts hills.)

Ubiquitous cats prowl between trash cans.

The green lights of minarets dot

the jumbled roofscape, loudspeakers waiting.

Tonight the same messenger will visit

every foreigner's dream. Yerushalayim

shel zahav: you dazzle and seduce, promise

a direct line to the One Who always takes

our calls. At the staggered hours

of our evening prayers, cellphones buzz

reminders to stop, drop, and praise.

Today's NaPoWriMo prompt offers "twenty little poetry projects," and challenges us to include all of them in a single poem.

It's a neat exercise; it definitely stretched me beyond my usual writing habits. I want to tighten it before publshing the next version; some of the lines prompted by the 20 prompts are (I think) terrific, and others don't quite flow. But the prompt was fun.

Yerushalayim shel zahav means "Jerusalem of gold."

April 28, 2014

Daily April poem: words taken from a news article

REMEMBRANCE

The narrow bridge of mourning

spans generations.

Overnight every dream shows

destruction. Ashes and bones.

Remembrance wells up.

Not only at the cemetery

but when planting, or

listening to the radio.

The moment of silence

lasts forever.

Today's NaPoWriMo prompt invites us to write poems using words borrowed from a newspaper article.

On the Jewish calendar today is Yom HaShoah. Most of the words in this poem came from The History of Holocaust Remembrance Day in Ha'aretz.

May the Source of Peace bring peace to all who mourn, and comfort to all who are bereaved.

April 27, 2014

Daily April poem: inspired by a photograph of baseball

WAHCONAH PARK

The wooden stands creak.

A forest of ballcaps and barrettes.

Teenagers text with T-1 thumbs.

Boys toss and catch

effortlessly eighteen

their calves limned with high socks.

Sunset delay: the lights flare

painting the dirt Georgia red

the field green as astroturf.

Between innings

children spin like dreidls

then race drunkenly across the grass.

By the end our mouths taste of hops.

Peanut shells crunch underfoot.

Kinsella tells us stories all the way home.

Today's NaPoWriMo prompt offers four photographs to inspire poetry. One of them is of a baseball field.

I named this poem after the old wooden ballpark in Pittsfield, and many of the sensory details were drawn from memories of games there.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers