Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 156

June 2, 2014

This Year's Revelation -- at Zeek

I have a new essay in Zeek. In this piece I draw on classical midrash and on Rabbis Without Borders thinking (as I did last year in the essay Being Meir) to make the argument that Torah belongs to all of us, no matter who we are -- and that God calls us to rise above the binaries which polarize us. Binaries within the Jewish community, binaries between us and other communities, binaries in the American political system -- what would happen if we could transcend those?

Here's a taste of the essay, a passage talking about the revelation at Sinai:

All of us were there. All of us heard. And what we heard, we heard according to our ability to understand. Torah comes to meet us wherever we are. Torah comes to lift us up, wherever we are. Torah comes to inspire us, wherever we are. And because each of us hears according to her or his own temperament and inclinations, we don’t always understand Torah in the same ways. But Torah doesn’t belong only to those who read it this way, or those who read it that way. Torah does not belong to religious liberals any more than it belongs to religious conservatives. Torah trumps those categories.

According to our midrashic tradition, God gives Torah to all of us — regardless of gender expression, sexual orientation, age, race, creed, color, class, political party — and it belongs to all of us, wherever we are. oes that seem too radical? Look back at the beginning of the midrash: God’s voice divided itself into every human language. For all that our tradition privileges Hebrew, revelation didn’t happen only in that language.

Revelation came in every language, because revelation belongs not only to Jews but to all creation. As my teacher Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi likes to say, God broadcasts on all channels; each religious tradition hears revelation on the channel to which we are attuned. The necessary corollary to that, of course, is that each religious tradition contains at least some ultimate truth. If some facet of the Infinite is revealed to each religious tradition, then it’s no longer possible to say that we have it right and they have it wrong.

Torah isn’t just for us, no matter how “us” is defined. [...]

I hope you'll click through and read the whole piece: This Year's Revelation.

Comments welcome.

June 1, 2014

Glimpses of a sweet Shabbat on City Island

First, a "City Island mojito" on Friday night:

Then, sweet davenen with "your band by the sea" at "your shul by the sea:"

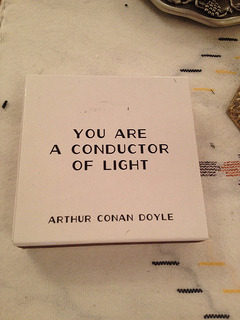

A message imprinted as I lit the Shabbat candles:

A Shabbat morning walk by the water before services:

...and then more wonderful davenen -- soul-uplifting music -- harmony -- Torah -- conversation -- learning -- joy.

This morning I'll be teaching a master class in spiritual writing, as the culminating event of my TBE Shabbaton. (The class is at 10am at Samuel Pell House, 586 City Island Avenue; $20 for non-members, bring writing implements and an open heart.) At noon I'll read poems from 70 faces and Waiting to Unfold, take questions and offer answers, and then enjoy some conversations and connecting before hopping in my car to head home to my family again.

Deep thanks to everyone at Temple Beth-El of City Island. You are a wonderful congregation and I'm so honored to have had the opportunity to sing, pray, teach, and learn with y'all!

May 30, 2014

Visiting a shul by the sea!

I'm off this weekend to Temple Beth-El of City Island, where I will be their scholar-in-residence as they celebrate their 80th anniversary with a Shabbaton of delicious practice, teaching, and togetherness! (I posted about this a while back.)

It's going to be an action-packed weekend. Tonight: kabbalat Shabbat services with "Your Band By the Sea." Tomorrow morning: services co-led by me, Reb David, and Reb Eva, followed by a public teaching at noon on the power of blessing. Tomorrow night: havdalah and a poetry reading in a private home. Sunday morning: a class on writing in spiritual life and then a poetry reading before I turn around and head home.

If you are in or around the New York city area, I'd love to see you at any of these events which are feasible for you! Logistical details again, for those who need them:

Friday and Saturday services / teaching at Temple Beth-El, 480 City Island Avenue

Sunday sessions at Samuel Pell House, 586 City Island Ave

( writing class: $20 for non-members, bring a notebook or laptop and an open heart)

Shabbat shalom to all!

May 29, 2014

Reparations and teshuvah

I want to call your attention to a remarkable essay published last week in the Atlantic, written by Ta-Nehisi Coates, called The Case for Reparations. It is long, and it is tremendously worthwhile. Here is one very brief quote, to pique your interest:

Having been enslaved for 250 years, black people were not left to their own devices. They were terrorized. In the Deep South, a second slavery ruled. In the North, legislatures, mayors, civic associations, banks, and citizens all colluded to pin black people into ghettos, where they were overcrowded, overcharged, and undereducated. Businesses discriminated against them, awarding them the worst jobs and the worst wages. Police brutalized them in the streets. And the notion that black lives, black bodies, and black wealth were rightful targets remained deeply rooted in the broader society. Now we have half-stepped away from our long centuries of despoilment, promising, “Never again.” But still we are haunted. It is as though we have run up a credit-card bill and, having pledged to charge no more, remain befuddled that the balance does not disappear. The effects of that balance, interest accruing daily, are all around us.

Once you've read it, I commend to you the following specifically Jewish responses:

Ask yourself | Jewschool. "Once you read this very long piece (very long but read it) and nod to the facts and shake your head at the horrific racism at all levels most likely, most probably, you will think: But my family didn’t live in the U.S. when it engaged in slavery. But that doesn’t matter. Anyone living in the United States benefits from the economic realities built on slavery. Every white person has been enriched by the segregation of neighborhoods, schools, and Federally insured lending practices. This goes well beyond being afraid anytime the police stop you or having people cross to the other side of the street when you pass at night."

The Jewish Case for Reparations -- to Blacks by Emily L. Hauser in the Jewish Daily Forward. "In the Hebrew tradition prophets cry out in the wilderness in part because their audience tends to be uninterested in the message. If the people were ready, after all, they wouldn’t need a prophet... We learn in Pirkei Avot that while we aren’t required to complete the task of righteousness, neither are we free to desist from it. Otherwise, we run the risk of (in Coates’s words) 'ignoring not just the sins of the past but the sins of the present and the certain sins of the future.'"

Late in the essay, Coates writes:

Perhaps after a serious discussion and debate—the kind that HR 40 proposes—we may find that the country can never fully repay African Americans. But we stand to discover much about ourselves in such a discussion—and that is perhaps what scares us. The idea of reparations is frightening not simply because we might lack the ability to pay. The idea of reparations threatens something much deeper—America’s heritage, history, and standing in the world.

Coates is calling us to a process of what my tradition calls teshuvah -- the internal work of discernment, atonement, and creating change.

I hope his essay sparks a major American communal conversation. And I especially hope that it sparks a conversation in the American Jewish community (or, more accurately, American Jewish communities -- we are many and varied!) about racism, about our complicity in racist systems, and about teshuvah.

May 28, 2014

On the Tent of Nations, destruction of orchards, and the path to peace

Valley of fruit trees: before and after. [Source.]

Several years ago, during the summer when I was living in Jerusalem, I had the opportunity to spend an evening with a group called the All Nations Café. (I blogged about it at the time, and also spoke about it from the bimah of my shul on erev Rosh Hashanah that year.) It was an incredibly powerful experience for me -- talking with Israelis, Palestinians, and internationals who were dedicated to peace and to forging connections across our differences. It's one thing for me as an American, living half a world away, to talk about my yearning for peace and coexistence. These folks were living that intention, and I admired them deeply.

I remember being particularly moved by hearing the story of the man on whose land we had gathered, a Palestinian man named Abed, who told us about his struggles to prove ownership of his family's land (despite holding papers dating from Ottoman times) and about the challenges which that entailed. I thought of the All Nations Café last week when I heard news about the destruction of the orchard at the Tent of Nations farm. (A side note: as I was writing this post the tentofnations.org website seemed to be down, but I think that webmasters are in the process of mirroring it at a new location: Tent of Nations.) My friend and colleague Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb wrote:

Daoud Nassar and his family at The Tent of Nations in the West Bank was invaded by the IDF and their environmental and educational farm destroyed. Entire fields of grapes, apples, apricots, almonds, figs were wiped out. Hundreds of fruitful trees were destroyed. Daoud and his family own the land, have papers dating from the Ottoman Empire...I feel this deeply. Daoud is my friend. Those of us who know Daoud have been deeply impacted by his compassion, nonviolence, resiliency, creativity, and commitment to community.

Daoud has posted about the destruction on the Tent of Nations Facebook page:

Today at 08.00, Israeli bulldozers came to the fertile valley of the farm where we planted fruit trees 10 years ago, and destroyed the terraces and all our trees there. More than 1500 apricot and apple trees as well as grape plants were smashed and destroyed.

(His post is here.) I'm embedding a ten-minute video about Tent of Nations, which includes a tour of the land and gives a good sense for what and where it is. I really recommend watching the video -- take ten minutes and watch, before you read the rest of this post. (If you can't see the embed, it's here at YouTube: Tent of Nations: we refuse to be enemies.)

One of the articles archived at Friends of Tent of Nations explains that "The Nassar farm is part of a parcel of land, including eight nearby Palestinian farming villages, that Israeli authorities hope to annex in order to expand the Gush Etzion settlements, whose population is around 50,000." I know that there is a housing shortage all over Israel; I feel certain that that plays into the Israeli government's desire to annex West Bank land in order to build. But I suspect that the current Israeli government is also acting out of the intention to continue establishing "facts on the ground."

That article explains that when the Israeli government first declared intention to confiscate the land, the Nasser family made the conscious choice "not to be enemies," and founded the Tent of Nations, an organization whose aims are "to build bridges between people of different backgrounds, and between people and land." Author Emma Halgren continues:

The Israeli authorities have forbidden any permanent infrastructure development on the site, as well as access to the electricity grid and public water, so the Nassars have refurbished seven underground caves, painting them, fitting them out with comfortable rugs and cushions and connecting them to electricity from a generator so that they could be used for meetings and other gatherings.

I remember a similar situation on Abed's land where the All Nations Café met -- because land ownership was contested by the Israeli authorities, no construction was permitted, so Abed and his family had refurbished a small cave and had also erected tents. I remember hearing about how the cultivation on Abed's land involved rain-collection and solar power, because the legal limbo of the land ownership dispute prohibited him from accessing the surrounding electrical or water systems.

In a 2010 post about Tent of Nations (Tent of Nations receives demolition orders), Rabbi Brant Rosen wrote:

Some background: Daoud’s farm has been in his family for four generations; his ancestor registered his land with the ruling Ottoman Empire and the Nassars still have the original deed. In 1991... the Israeli military initiated proceedings to expropriate the Nassar family farm, which happens to be located between two Jewish settlements in the Gush Etzion Block.

Despite Daoud’s irrefutable proof of his family’s ownership of the land, the legal battle over it has stretched on for well over two decades – and the Nassar family has spent over $140,000 in legal fees to date. Up until now, their case has been essentially stuck in Israeli legal bureaucratic limbo.

In the meantime, the Nassar family has used their land to establish “The Tent of Nations” an inspirational center that provides arts, drama, and education to the children of the villages and refugee camps of the region. Daoud and his family have also established a Women’s Educational Center offering classes in computer literacy, English, and leadership training. (Many rabbis and rabbinical students are familiar with Tent of Nations as a primary destination for Encounter – a well-known educational program that promotes coexistence by introducing Jewish Diaspora leaders to Palestinian life.)

I meant to go on an Encounter program during the summer I was living in Israel, but it was cancelled on account of violence. Many of my rabbinic friends and colleagues have visited Tent of Nations, and I hope to have the chance to do so someday as well.

Rabbi Rosen refers to Daoud Nassar's "irrefutable" proof of ownership; I assume he means the Ottomon-era deed to the land. Unfortunately for Daoud and his family, Israel maintains a policy of not recognizing Ottomon or British deeds in the West Bank (see Displacing: House Demolitions and Closure at ICAHD), so that deed isn't enough to protect the farm or the organization established thereupon. Because Israel doesn't recognize Ottoman or British deeds, the Nassar family has funded an extensive survey to further prove ownership of their land, but everything I've read suggests that the survey's findings are in a kind of legal limbo.

Recently I posted about a dispatch from Paul Salopek in Jerusalem. I quoted Paul: "In a 5,000-year-old city where changes in neighborhood zoning rules earn international headlines—such is the ferocity of ownership over each square inch of Jerusalem—we orbit painful questions of identity, of zealotry, of personal loss, of national survival." This is surely most intensely true in Jerusalem (because everything is more intense in Jerusalem!), but Jerusalem is also a microcosm of larger struggles for ownership and identity which persist across the land.

What precipitated this demolition of 1500 fruit trees and adjacent vineyards? A note from attorney Sami Khoury explains that the Israeli military authorities recently served papers to the Nassars indicating that their orchards were planted on state land and that the trees therefore constituted tresspassing. (There's something vaguely Kafkaesque, to me, about accusing fruit trees of being tresspassers...) Although the Nassars immediately filed an appeal with the military court arguing that the orchards were planted not on state land but on their own land -- and although legally no demolitions are supposed to take place while an appeal is pending -- the orchard was uprooted shortly thereafter. (There's an extensive timeline of events at the bottom of Rabbi Rosen's more recent post about Tent of Nations.)

I empathize with my Israeli friends who struggle for housing in a country where apartments are in short supply. And I'm sure that those who live in the settlements which surround the Tent of Nations land would be happy to have that land for their own building purposes. When I was in Israel I met several bloggers, one of whom was then living in Neve Daniel, one of the settlements adjacent to the Nassar farm; she mentioned the housing shortage, as did my friends in Tel Aviv and in Jerusalem. But bulldozing fruit trees which have been so lovingly cultivated goes against the grain of my understanding of what Judaism is about.

The Torah teaches that we should not destroy fruit trees even in a time of war, and mainstream Jewish interpretation has understood this as an edict against any act of despoiling, in peacetime as well as war. Writes Rabbi Arthur Waskow (in an email to the OHALAH rabbinic email list, quoted with permission):

Torah could hardly be clearer. This early step in protecting both the Earth and human beings from "scorched earth" destruction helped create the tradition of menshlichkeit that is the best fruit of the Jewish people. Was it for cutting down that fruit and these verses of the Tree of Life that generations worked so hard to create a "Jewish" state?

For another perspective on how Torah prohibits the destruction of trees, see the essay Bal Tashhit: the Torah Prohibits Wasteful Destruction by Rabbi Norman Lamm, former president of the mainline Orthodox institution Yeshiva University -- hardly a lefty peacenik.

Destroying orchards is not ethical. Even if there is a housing shortage in the surrounding towns. In this era of consciousness about our footprint on the earth, there's no excuse for destroying productive agricultural land in order to build houses, and that may be especially true in the Middle East where rainfall and arable land are both limited. Because the Nassar farm is prohibited from accessing local water and power systems, they have developed (and are teaching others) sustainable agricultural practices, using solar power and rainwater, filtering "grey water" for reuse, and so on. This farm could be an exemplar to others of how to live lightly on the land.

Beyond that: destroying someone's farm and livelihood is not ethical; and kal v'chomer, when that farm is also home to a nonprofit organization which does so much good work, the destruction becomes even more shameful. One of Tent of Nations' projects is instruction in English and in computer skills for women in the neighboring village of Nahalin. These women are unable to leave their village because of travel restrictions (imposed by Israel), and would otherwise have few opportunities for education and personal development. (You can read more about that program in this April 2014 dispatch.) Tent of Nations also provides summer camp programs for local children from Bethlehem and nearby refugee camps, where the kids engage in projects like putting on Shakespeare plays and making mosaics out of broken tiles scavenged from rubble. These good works should not be met with this kind of destruction.

Beyond that: what impression can this possibly give to the wider world, except that Israel is destructive and power-hungry, trampling on the rights of the poor? That is not the Israel I know and love. But that is the Israel which is making itself manifest in the eyes of the world, and that grieves me.

I am among the many who believe that settlements are an obstacle to peace. (The recent Pew study showed that a plurality of American Jews hold this understanding.) I've been writing about this for years -- see West Bank settlements: obstacles on the road to peace, my liveblogging of a 2009 panel discussion featuring Akiva Eldar, chief political columnist and writer at Ha'aretz; Hagit Ofran, the director of Settlement Watch, a project of שלום עכשיו / Peace Now; and Scott Lasensky, a Senior Research Associate at the Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention.

It seems obvious to me that the more Israel builds up the settlements, the more those settlements carve the West Bank into a disconnected block of Swiss cheese. And the more the West Bank is carved-up in that manner, the less plausible it becomes to imagine a Palestinian state there. Many of those who support settlement expansion agree with me that building settlements negates the possibility of a two-state solution -- there are members of the Knesset who support settlement expansion for precisely this reason. If there will be no Palestinian state, then either Israel must choose a path of perennial occupation, or Israel must choose to grant citizenship to the Palestinians living in Gaza and the West Bank.

I don't think that perennial occupation is sustainable. I also don't think it is ethical, and I believe that it is damaging both to the lives of those who live under occupation and to the souls of those who perpetuate the occupation. Is it time to give up on the two-state solution and instead work toward a binational state in which all citizens have equal rights? I don't pretend to have the answer to that question. But it seems to me that as settlements expand, we approach a moment when the question will become moot. And I think it's especially saddening when the intention of expanding the settlements leads to the destruction of an orchard like the one belonging to Daoud Nassar and his family.

If you're interested in learning more about how you can help Tent of Nations rebuild, I'm told the best way to stay abreast of the situation is to "like" their Facebook page, so that you will receive their updates on how they plan to move forward.

May 27, 2014

All at once

From God's high vantage

-- spacetime spread out

like an endless scroll --

every trip I've taken

between these two places

is happening right now.

I'm passing myself

at 30,000 feet: seventeen

and flying home for Pesach

clutching a grey sweatshirt

from the college my parents

don't yet know I've chosen,

thirty-five with diaper bag

full of earplugs to hand out

when the baby starts to scream.

On a plane I haven't taken

God can see me flying back

with my black suit folded tight.

Knowledge I never wanted

from the tree I know everyone

eventually tastes, eyes watering

from the fiery sword

barring me from the home

to which no one can return.

I'm spending a few days in south Texas, visiting my parents and reintroducing my son to the sights, sounds, and scents of my childhood hometown. Flying down here a few days ago, I was struck by the vivid notion that if I could see the world as God sees it, I would see all of my trips between my birthplace and the Berkshires at the same time...including trips I haven't taken yet.

The final two stanzas allude to the story from early in the book of Bereshit (Genesis) when a cherub with a flaming sword is stationed at the entrance to the Garden of Eden to keep Adam and Chava out. One can read the Eden story as a lesson about childhood and about the bittersweet implications of gaining knowledge and losing innocence. No one can remain in Eden forever.

Wishing everyone blessings on this 42nd day of the Omer.

May 25, 2014

Rituals, spiritual fidelity, and turning toward God (Naso)

Next weekend I'll be the scholar-in-residence at a Shabbaton at Temple Beth El of City Island. In anticipation of my visit, they graciously invited me to post a d'var Torah at their rabbinic blog. For the sake of completeness, I'm also archiving it here. Enjoy!

In this week’s Torah portion (Naso) is the strange ritual of the Sotah, which on its face concerns an allegedly unfaithful wife, a jealous husband, and a magic brew of water and dust. When our sages say of Torah, “Turn it and turn it, for everything is in it,” I believe they invited us to turn this Sotah passage so it reveals not only old-paradigm patriarchy and heterocentrism, but also deep wisdom for today. Before we can turn it, though, we need to look with open eyes at what it is we’re turning.

Here is the p’shat (the simple surface meaning) of the Sotah ritual. If a husband suspects his wife of infidelity, he should bring her to the priest with an unseasoned grain offering. The priest will dissolve dust from the temple floor in a vessel of sacred water; write the words of a magic spell on a piece of parchment; dissolve those words in the water; and make the woman drink it. The spell indicates that if she was unfaithful, her thigh will sag and her belly will distend. (Some commentators read these words to imply miscarriage; others see them as describing an immediately visible physical response to drinking these “waters of bitterness.”) If the woman has not been unfaithful, then nothing will happen and/or she will remain able to conceive. Either way, that’s the end of the strange Sotah story.

Almost everything about the Sotah ritual challenges our the modern sensibility. First, the gender inequality: a man could accuse his wife of adultery, but there’s no parallel ritual for a woman suspecting her husband of infidelity. While a woman’s sexuality is “owned” by her father or husband, a man’s sexuality is his own and untestable. Second, the Sotah assumes heterosexuality: there’s no ritual for a same-sex couple. Third, there’s the uncomfortable suggestion that an unfaithful woman will inevitably miscarry or become infertile, implying that anyone who miscarries or is infertile may be suspect. I have a sense for how emotionally and spiritually devastating miscarriage and infertility can be in the modern world, and I have no doubt that these experiences were equally powerful for our female ancestors. To link the pain of infertility with this kind of moral judgment adds insult to injury. For these reasons and others, we cannot read the Sotah to guide difficulties among intimate partners in today’s world. We need to turn it around to make it meaningful.

What if we read the Sotah, instead, as a psychological drama in which its actors represent different parts of the self? Through that lens, the verses about the Sotah tell an entirely different story: here’s what to do if I come to feel that some part of me has betrayed the greater unity to which I aspire. First, I must bring my whole self to a holy place, a place of prayer and connection with divinity. Body, heart, mind, and soul: all of me must present in order to move forward. In that holy place, I meet with a spiritual facilitator, someone who has a deep connection with God (symbolized by the Sotah ritual of appearing before a priest). With that person’s help, I articulate where I fear that I went wrong.

Then there’s a ritual of washing-away my misdeed. We write the words down and then let them dissolve. I drink from the living waters in which my misdeeds have dissolved — a way of internalizing, literally taking-into-myself, how my mistakes have been forgiven and washed away (symbolized by the physical drinking of the Sotah potion). If my teshuvah process is incomplete and I haven’t wholly integrated forgiveness, this process may make me feel worse (symbolized by the physical effects of drinking the Sotah potion when one is “guilty”). But if I’m able to release myself from my own misdeeds, then I come away with a clean slate, ready to begin again (symbolized by the Sotah promise of fertility).

Seen in this way, the ritual of the Sotah becomes a kind of spiritual direction session, an opportunity to work with a trained facilitator to fully effect the transformation of teshuvah, repentance and return.

In the writings of the Prophets, physical infidelity often is a metaphor for spiritual infidelity. Hosea in particular works with this theme at length. God is the “husband” whose “wife” – the people Israel – strays to other gods. (The patriarchal / heterocentrist language is Hosea’s; we might reframe his words as a teaching that the Holy Blessed One, a unity beyond all gender and division, enters into covenant with us and, in our human understanding, feels “hurt” when we stray.) Although God responds to this with furious anger for a time, God’s ultimate response is one of love. God is always ready to take us back.

Hosea teaches that teshuvah is endlessly possible, and that no matter what our transgressions might be, our covenant with the Holy Blessed One is reparable and will endure. Hosea too can be troubling if read as a prescription for contemporary marital counseling. But what I find most remarkable in Hosea is not his bitterness, but the turn he makes from anguish to reconciliation. Teshuvah, he argues passionately, is always possible and necessary. No matter how deeply we have betrayed our Beloved, we can and must make the shift of turning ourselves back in the right direction. And if we can make that leap of teshuvah — at once the most impossibly difficult, and profoundly simple, act in our lexicon — we will be received with open arms.

On June 3, just a few short days from now, we’ll reach the festival of Shavuot, our early-summer festival of first fruits and revelation, the day we symbolically re-receive Torah at Mount Sinai. Many of us may associate teshuvah, turning-toward or returning-to God, with Elul and the Days of Awe — a season still many months away. What does Shavuot have to do with teshuvah?

The Days of Awe come at the end of an intense period of reflection, introspection, and the inner soul-work of teshuvah. According to one way of thinking, that period begins with Tisha b’Av, the low point in our festival year when we recall the destruction of both Temples and mourn the brokenness of creation. After Tisha b’Av we count 49 days — seven weeks — until Rosh Hashanah, the beginning of the Days of Awe. Seven weeks for teshuvah and soul-work culminate in one of our year’s biggest opportunities for transformation and connection with God. (I learned this from Reb Zalman, who heard it from Cantor Michael Esformes.)

Shavuot too comes at the end of a seven-week period of reflection, introspection, and inner soul-work: the period of counting Omer, which links Pesach with Shavuot, liberation with revelation. The Omer period now finishing is our spring season of teshuvah; the months of Av and Elul before Rosh Hashanah are our fall season of teshuvah.

Teshuvah also is a monthly, weekly, and even daily practice — but our tradition gives us two corridors of the year to focus deeply on this work together. And when we do this work of teshuvah, and release ourselves from our misdeeds and our old baggage, we become able to stand wholly at Sinai and receive the new Torah which God will reveal this year.

Shavuot is seen in rabbinic tradition as the marriage between God and Israel. In the rabbinic imagination, God is the groom; Israel, the bride; the Torah, our ketubah outlining our and God’s mutual promises and responsibilities. (Here, too, we can shift the traditional gender categories as needed in order to make the metaphor resonant in today’s language.) There’s another midrash which suggests that God held Mount Sinai over us like an inverted barrel, threatening that if we didn’t accept the Torah, God would drop the mountain and bury us there; but the marriage midrash recasts it, arguing instead that Sinai suspended over our heads was in fact our beautiful chuppah or marriage canopy!

In reading about the Sotah a few days before our “wedding anniversary,” we remind ourselves that in any relationship there will be ebbs and flows of connection. And in any relationship, a leap of faith is necessary. One doesn’t enter into a marriage saying “tell me everything that might go wrong in the coming decades and then I’ll decide whether to commit.” We join with one another, and with God, in perpetual hope. And when we inevitably feel pulled astray, we trust that repair is possible. We trust that we can return to each other, that we can return to our deepest selves, that we can return to the Holy One of Blessing — and be received in love.

Keyn yehi ratzon: may it be so.

May 21, 2014

The scent of memory

I'd never encountered lilacs until the end of my first year of college. That was my first year living in New England, and my first Berkshire spring. Suddenly, as exams approached and the end of the year loomed, the tall bushes alongside the President's house and all around town sprouted flowers, and their fragrance was unbelievably beautiful. I remember my then-boyfriend picking sprays of lilac and bringing them to me in my dorm room. (That boyfriend has now been my spouse for almost sixteen years.)

I'd never encountered lilacs until the end of my first year of college. That was my first year living in New England, and my first Berkshire spring. Suddenly, as exams approached and the end of the year loomed, the tall bushes alongside the President's house and all around town sprouted flowers, and their fragrance was unbelievably beautiful. I remember my then-boyfriend picking sprays of lilac and bringing them to me in my dorm room. (That boyfriend has now been my spouse for almost sixteen years.)

I loved the lilacs' color palette of white and pale lavendar and deep purple. I loved the way they transformed otherwise ordinary greenery into a profusion of color. The color of lilacs reminded me of mountain laurels, which bloomed all around my childhood house in San Antonio in the spring; the scent reminded me of wisteria. But lilacs aren't quite either of those things. They are deeply, unmistakeably, themselves. I will always associate them with spring in the Berkshires when/where they and I first met.

(Alas, no one has developed a way to share scent through the internet. So unless you know the scent of lilacs and can hyperlink yourself to that memory, I can't share it with you, though I wish I could.)

This morning as I exited my car and made my way to Tunnel City Coffee for Torah study with the local Jewish clergy, the scent of lilacs caught me by surprise and quite literally stopped me in my tracks. I looked over and saw that the tall lilac bushes alongside the parking lot have, since last week, exploded like fireworks into a wild riot of lilac blossoms. I stood there and just breathed for a few moments, drawing their scent deep into my lungs, reawakening the neurons which called forth all of my lilac memories.

Now that I've lived here for many years, the season of lilacs carries other associations -- not so much the end of the school year (though the coffee shop this morning was packed with students frantically preparing for exams) as the long-awaited coming of green to our hillsides, the counting of the Omer and eager anticipation of Shavuot, the time when the forsythia bushes are shedding their yellow blossoms in favor of new leaves, the cusp of what will become summertime but isn't quite there yet.

I recited the blessing over blooming trees with our son some time ago. (Well -- we said the blessing after a fashion, in our own way.) But this morning as I scented the lilacs on the breeze, I said a shehecheyanu, the blessing sanctifying time. Blessed are You, Adonai our God, Source of all being, Who has kept me alive, sustained me, and enabled me to reach this moment! And then I went on my way... but I will carry the scent of lilacs with me through my day, with gratitude and with a smile.

May 20, 2014

Paul in Jerusalem

Some weeks ago, I wrote a poem inspired by Paul Salopek's Out of Eden walk, his seven-year quest to cover -- on foot -- the original migratory journey of humankind. (You can find my poem on the Out of Eden blog -- Couplets and kilometers -- and it's now available in April Dailies, which you can read about here.) If you have any interest in travel, I can't commend Paul's work to you highly enough. You can read his chronicle of his journey at National Geographic, and on the companion website you can listen to audio clips, look at photographs, and encounter other multimedia glimpses of where he's been.

As it happens, these last several weeks he's been walking through some places to which I have a deep attachment. (Me and just a few other people, as it happens.) His most recent blog post is about a city I revisited only six weeks ago:

"This place is too complicated," says Yuval Ben-Ami, my walking partner in Jerusalem. He is a big man with gentle eyes. A writer. A radio host. A street singer—a bard. He has hiked Israel’s entire perimeter along its borders. He knows its village bus stations. Its cheap Ethiopian restaurants. Its most scenic battlefields. He has been up all night thinking. "The only way we can do this--"

And with a blue pen he draws a curlicue...

That's from Vortex: Walking Jerusalem, the most recent dispatch from Paul. Later in the essay he writes:

In a 5,000-year-old city where changes in neighborhood zoning rules earn international headlines—such is the ferocity of ownership over each square inch of Jerusalem—we orbit painful questions of identity, of zealotry, of personal loss, of national survival. We trudge over a hundred lonesome boundaries—invisible and monumental—that Israeli and Palestinian Jerusalemites do not cross...

I found his post incredibly resonant with my own sense of the city. It's poignant, surprising, and thoughtful.

Once you read it, click through to the walking Jerusalem map. You can see the dotted line of his walking journey through the city, and if you click on any one of the little icons, you'll be taken to a photograph taken in that spot. (As it happens, one of the first icons I clicked turned out to be the bookstore where I went for lunch with Bethlehem Blogger -- the place where I purchased Crossing Qalandiya, which I just reviewed recently.)

I'm looking forward to continuing to read Paul's dispatches -- especially as he walks through places which are entirely unknown to me. But there's something especially powerful about reading his words, and seeing his photos, from a place which I am fortunate enough to already know and love.

May 18, 2014

Happy Lag B'Omer!

Hey, did you know that today is a Jewish holiday? Today is the 33rd day of the Omer. Since Hebrew numerals are also letters, today is called Lag B'Omer -- the letters for 33 spell out the word לג or lag.

Hey, did you know that today is a Jewish holiday? Today is the 33rd day of the Omer. Since Hebrew numerals are also letters, today is called Lag B'Omer -- the letters for 33 spell out the word לג or lag.

Today is the yahrzeit, the death-anniversary, of the sage Shimon bar Yochai. He lived during the first century of the Common Era, and Jewish tradition says that he wrote the Zohar (the central work of Jewish mysticism.)

Tradition says he brought down the wisdom of the Zohar, which was passed-on orally until it was finally committed to print by Moshe de Leon in 13th-century Spain. Those with a more historical-critical bent might suggest instead that de Leon wrote the Zohar in an intentionally old-fashioned Aramaic. Either way, today is a day when we cultivate gratitude for the Zohar's spiritual fire.

"Zohar" means "splendor" or "radiance." It's a source of great light, in the sense of illumination and wisdom and insight. Maybe that's part of why we traditionally light bonfires on Lag b'Omer -- to send literal sparks flying upward as a reminder of the intellectual and spiritual sparks of our mystical tradition and its wisdom.

For more on this holiday, you can check out my Lag B'Omer category. I'm still quite fond of my 2009 post The bonfire of the expansive heart, which offers a few different classical interpretations of Lag b'Omer (the end of a plague which had been caused by Rabbi Akiva's students not respecting one another; the end of a Roman massacre of Jews during the bar Kokhba revolt), and then focuses on a teaching from Rabbi Zvi Elimelech of Dinov which offers some beautiful thoughts about what it means to have a good heart.

May we all experience the Omer as a time for cultivating and expressing the best of our hearts, and a time for (as Rabbi Zvi Elimelech writes) "bringing together opposites in friendship." Kein yehi ratzon -- may it be so!

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers