Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 155

June 16, 2014

Morning gratitude psalm

For my iPad

with its velvety cover.

For bringing forth

a world of praise

with the tap of a finger.

For the crush of my tefillin bag.

For little houses

filled with words.

For places where I am exposed

and where I'm held safe.

For the choir of angels

even the one who sings off-key.

For women in headscarves

bearing witness

there is no god but God.

For the currents which carry us.

For the earth which cups my chair

in her compassionate palm.

For the soul

You restore to me.

Last week at the retreat for Jewish and Muslim emerging religious leaders, there was a time slot when the alumna facilitators and spiritual advisors shared different spiritual practices. One of my colleagues led a guided meditation; another, Sufi chanting; a third, gratitude yoga; and I offered a workshop in writing the psalms of our hearts. (This was a tiny taste of the workshop I led recently on City Island, which is in turn a tiny taste of the week-long class I taught at the ALEPH Kallah a few years back.)

I did the writing assignment myself during class time, and here's what unfolded -- a psalm of gratitude for morning prayer. Early that same morning I had gone to pre-dawn zhikr; then some of my Muslim sisters with whom I had davened zhikr joined us for shacharit, Jewish morning prayer. All of these things found their way into my psalm.

All feedback is welcome.

Deep thanks to the Henry Luce Foundation for their gracious support of this incredible retreat program.

June 15, 2014

Bloggers and beer

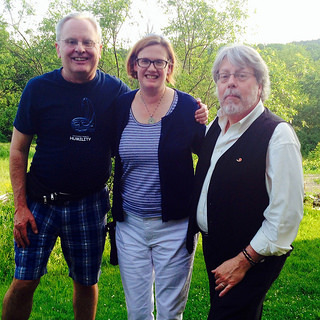

Peter, Rachel, James: three bloggers in person!

Some years ago -- it was longer ago than I realized until I went to dig up the link; it was way back in 2008! -- I posted A minister and a rabbi walk into a coffee shop, about meeting UCC pastor and blogger James Lumsden of When Love Comes to Town after he moved to the Berkshires. Tonight I met up with James once again and also with his wife Di as well as the two visitors they recently welcomed to town, Peter and Joyce, visiting from Thunder Bay, Ontario.

Peter and I have been corresponding for years. I've read his blog in a few different incarnations, and he's a frequent commenter here at Velveteen Rabbi. Most recently we just barely missed each other in Jerusalem. When I arrived there in March with my family, he and Joyce had just finished a three-month stint with the Ecumenical Accompaniment Program in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI) of the World Council of Churches. (Here's one of his posts about that work: Being faithful, or trying to be so.)

This evening we five met at one of my favorite places in the neighborhood, a venerable pub called the Old Forge, where we enjoyed a variety of fine beers and some truly terrific buffalo wings as well as delightful and wide-ranging conversation. We talked about travels in the Middle East, of course; also about the life of ministry (from which Joyce recently retired), about my congregation and my family, about food and art, parenthood, films, and more.

I'm honored that Peter and Joyce took time out of their brief visit to the Berkshires to meet me for a pint. And I'm delighted by the small-world quality of my corner of the internet, where people I've known for years as digital presences sometimes become in-person friends, too.

June 13, 2014

Spiritual life in the open

At my two most recent poetry readings, during the Q-and-A session, someone has asked me what it's like to live my life so publicly and to expose my heart in my poetry as I do. The truth is, writing poems of miscarriage and healing, or poems of postpartum depression, didn't feel "brave." It just felt ordinary. I make sense of my life through writing. I always have, ever since the adolescent days when I kept a diary in a series of cloth-bound notebooks which I kept proudly on my shelf. Sharing my writing with others who might be walking a similar path has become one of the ways I minister to people around me. I have learned that when I share my experiences (whether sweet or bitter) I feel less alone. And people who read what I write often tell me that they feel less alone when they read my words, too, and that feels like an added blessing.

At my two most recent poetry readings, during the Q-and-A session, someone has asked me what it's like to live my life so publicly and to expose my heart in my poetry as I do. The truth is, writing poems of miscarriage and healing, or poems of postpartum depression, didn't feel "brave." It just felt ordinary. I make sense of my life through writing. I always have, ever since the adolescent days when I kept a diary in a series of cloth-bound notebooks which I kept proudly on my shelf. Sharing my writing with others who might be walking a similar path has become one of the ways I minister to people around me. I have learned that when I share my experiences (whether sweet or bitter) I feel less alone. And people who read what I write often tell me that they feel less alone when they read my words, too, and that feels like an added blessing.

But I do think a lot about how my openness, particularly my poems of early motherhood, may someday impact our son. I hope and pray that when he is old enough to read Waiting to Unfold, he sees the love which was always a throughline, always present, even when I was struggling to find myself amid the waves of postpartum depression which threatened to drag me down. But I know that as the child of a poet, and the child of a rabbi, he may come to resent the ways in which my openness about my life means that his life is sometimes visible to the outside world, too. Maybe you've noticed that I rarely use his name on the blog anymore -- not because it's a secret, not because it's difficult to unearth, but because I'm becoming conscious that I don't want my life story (in which he is certainly a star!) to overshadow his narrative about himself.

I know that many of you, like me, have been avid readers of Rabbi Phyllis Sommer and Rabbi Michael Sommer's Superman Sam blog. They began the blog when one of their four children was diagnosed with leukemia. They posted there religiously about the ups and downs of his treatment; the blog is where where so many of us, me included, got to know their beautiful family and their extraordinary son Sam, may his memory be a blessing. I admire them for that -- and I admire them even more the way they've continued writing about their journey of grief in the wake of their son's death. When I read their blog now, I see them modeling for all of us how to make our way through the murky waters of grief. They are showing us, by example, how to grieve out loud and how to let other people offer care and love in response. They are living their spiritual lives in the open, and they teach me more than I can say.

Stories are always interconnected. I can't tell the story of my life without at least touching on a lot of other people's stories: my parents, my grandparents, my teachers, my spouse and child, my friends. I'm tremendously grateful for that. I have a sense for how fortunate I am to have a life which is so rich in connections. And sometimes those connections mean I need to think about what I write and how I share. Not everyone favors the spiritual practice of living one's life in the wide-open. And not every story is mine to tell, even if it impacts my story in a profound way. Why am I thinking about this now? Someone in my family is ill, and had an emergency hospitalization recently. (Not my spouse or my child, thank God.) This person's journey with sickness and health is not my story to tell. And yet it feels dishonest to blog as though nothing were happening -- as though I weren't holding this loved one in prayer every day.

At Shabbat services recently, when I shared the names of those in need of healing in my synagogue community, my voice quivered and my composure wavered. It would feel like a lie of omission not to explain to my community why praying for healing right now sometimes brings me to tears. And if I were to wall part of myself off, and keep my emotions at bay, I wouldn't be an effective leader of davenen (prayer) or an effective pastoral counselor. I can only do my work as a rabbi when I'm willing to bring my authentic self to bear on whatever's in front of me. Besides, I don't want to fall into the easy fallacy of imagining that I always have to pretend that "nothing's wrong" -- that as a clergyperson it's my job to always be cheerful and always keep my own sorrows hidden from those whom I serve.

And yet I also don't want my community to feel that they need to bear me up -- and I don't want my loved one who is sick to feel that I have disclosed what wasn't mine to share. I strive to find the right balance between being honest, and being appropriately circumspect. In a sense it's no different from what I was already doing. This is life in the world, if one seeks to be connected and also to have decent boundaries. This is the writing life. This is the rabbinic life. But I'm aware that it feels heightened now.

No sooner did my loved one leave the hospital than I learned that my beloved teacher Reb Zalman had been hospitalized. (Here's a recording of one of the teachings he offered at Shavuot just a few days before he fell ill.) At the retreat for Jewish and Muslim emerging religious leaders earlier this week, I dedicated one session to him, in hopes that the merit of our learning would accrue toward his healing. A friend of mine offered a healing prayer on his behalf at our pre-dawn zhikr, as well. Of course, he has been reminding us for years that this "deployment" -- which is to say, this incarnation; this lifetime in which he has felt deployed by God to do holy work -- will not last forever. And God willing he will be fully healed from this illness and will return to good health! But it's one thing to know intellectually that someone I love will not live forever; it's another thing to try to face that truth in my heart, in my body, in my soul.

Loss (both immediate, and anticipated) is a part of life as we know it. Every soul which lives in this world eventually rejoins the great Mystery we name as God. Those who are left behind experience a range of emotion as we navigate loss. I know that this is how the world works. That doesn't mean I always have an easy time accepting it. I don't want to lose anyone I love. And I don't want anyone I love to suffer. And I know that eventually people I love will move beyond where I can reach, and I know that suffering is part of this embodied existence, try as we might to eradicate it or wish it away. All I can do is sit with these truths, and sit with my overflowing feelings of love and compassion, and try not to stifle any of what's arising.

With some dispassionate part of my brain I can't help noticing that it feels strange to walk through the ordinary world when someone I love is ill. There's a peculiar temptation to stop everyone I see, to shake them and demand: how can you be going about your day in such a mundane way? Don't you know that my loved one is ill? Don't you know that the world is tilting off its axis? Of course, the world was (and is) rotating just fine, even though I've been feeling personally off-kilter. But that metaphor is the best way I can describe the tumult of feelings which can come along with a loved one being ill. Everything is normal, except that it isn't. This isn't what normal used to be. There's no knowing when or whether that old normal will return.

As a rabbi, I've tended to many people and families who are in this position. But I don't know that that makes it any easier for me to navigate these waters gracefully myself. What else can it be besides another opportunity for practice. Another opportunity to try to bring kindness, mindfulness, connection-with-God to bear on whatever's unfolding. Another opportunity to write my way to understanding. (As E.M. Forster wrote, "How do I know what I think until I see what I say?") And another opportunity to share my spiritual journey with y'all -- assuming that I can continue to find a way to write about it which doesn't explose my loved ones, but does open up what's happening in my heart.

June 12, 2014

On the Presbyterian conversation about divestment from Caterpillar et al.

I've seen some concern lately in the Jewish community about the conversation which some of our Christian cousins -- specifically the Presbyterian Church of the United States of America (PCUSA) -- are having about divestment and Israel. I think it's possible that some of the concern comes from lack of clarity about what the Presbyterians are actually discussing.

I've seen some concern lately in the Jewish community about the conversation which some of our Christian cousins -- specifically the Presbyterian Church of the United States of America (PCUSA) -- are having about divestment and Israel. I think it's possible that some of the concern comes from lack of clarity about what the Presbyterians are actually discussing.

The Presbyterian church is not talking about divesting from Israel. (Indeed: one cannot divest from a country, only from a corporation.) They're considering withdrawing their church investments from three American-based multinational companies which make certain kinds of equipment used by the military.

Here's a link to the report which lays out their recommendations. And, from that report, here are their reasons for suggesting divestment from these three companies, in brief:

Caterpillar sells heavy equipment (e.g. the armored IDF Caterpillar D9) used by the Israeli government in military and police actions to demolish Palestinian homes and agricultural lands. (See On the Tent of Nations, destruction of orchards, and the path to peace.) It also sells heavy equipment used in the West Bank for construction of, among other things, settlements, roads which are solely open to settlers, and the construction of the Separation Barrier.

Hewlett-Packard sells hardware to the Israeli Navy, including Electronic Data Systems which provide biometric ID used to monitor Palestinians (and not used to monitor Israelis) at several checkpoints in the West Bank and in the separate Palestinian road system.

Motorola sells an integrated communications system, known as "Mountain Rose," to the Israeli government which uses it for military communications. They also provide equipment for the IDF, including ruggedized smartphones, and have signed a contract to provide the next generation of this technology to the IDF.

The conversation about divestment comes from the church's Committee on Mission Responsibility Through Investment (CMRTI), a denominational committee which works to ensure that their investments are aligned with their stated religious values. The Presbyterian Church has an official policy of only investing in businesses which are pursuing peaceful endeavors.

The PCUSA has made these sorts of decisions before. Early in the church's history they withdrew investments from companies which produce alcohol. In 1980, they began withdrawing investments from corporations involved in military production. As one Presbyterian writes, PCUSA's "social witness policy prohibits [us] from investing in industries that harm people. We do not, for example, invest in gambling, firearms, pornography, and alcohol." I can understand why the CMRTI thinks that if their church seeks to only invest in businesses which do the work of peace, these corporations are not a fitting place for their investments.

Some of the Jewish critique of the church's process seeks to make the case that focusing divestment and other economic attention on what happens in Israel is inappropriate if equal attention isn't also paid to other places. But to me it makes perfect sense that the church would pay attention to "the Holy Land." It's easy for us, as Jews, to forget that Christians have a two-thousand-year-old attachment to this place. Don't we all pay attention to places which are emotionally and spiritually meaningful to us?

It may also be noteworthy that the PCUSA's investing agencies continue to hold stock in companies which do business in Israel, among them Intel, Oracle, Coca‐Cola, Procter & Gamble, IBM, Microsoft, McDonald's and American Express. (And that they have chosen at various times to withdraw investments from companies which did business in South Africa, Burma, and Sudan -- companies doing business in Israel are not the only subjects of their attention.) They're considering withdrawing their investments specifically from these three companies which produce implements used in a militarized or militaristic manner -- not from Israeli businesses or from other businesses working in Israel.

I don't imagine that any of these corporations would be substantially impacted by the removal of the PCUSA's funds. The divestment from Caterpillar et al. would be merely symbolic. But religous institutions frequently work in the realm of the "merely symbolic," and I can understand how this gesture could be meaningful -- both to members of this church, and to my friends who are working toward a just and lasting peace.

When I hear the anxiety from sectors of the Jewish community which oppose this divestment, I hear fear that this divestment proposal is thinly-veiled antisemitism; that it delegitimizes Israel; and that its passage will lead to further anti-Israel feeling. I see the situation differently. To me, what "delegitimizes" Israel is the injustices of the occupation, and I don't think it's appropriate to try to shame the Presbyterians into continuing to invest in corporations which do work they deem unethical.

The prophet Isaiah -- author of a holy text shared by Jews and Christians, though we sometimes interpret it in different ways -- speaks of the day when we will beat our guns into plowshares. (Some artists are taking that call to heart even now, turning guns into religious art, or into musical instruments.) Choosing not to invest in companies which make implements of war -- whether they be guns, or military communications systems -- is one way of embracing that prophetic vision of peace.

The gifts of the labyrinth

The first full day of this retreat for Jewish and Muslim emerging religious leaders was intense and busy. From morning prayer to conversations over breakfast to beginning to guide my small group through our group project to an "intra-faith dialogue" session (each group convened in its own prayer space and talked about whatever's arising for us so far.) Conversations over lunch. A faculty meeting. Two hours of learning with Dr. Judith Plaskow (which merits its own post, God knows.) More group project planning.

By late afternoon I was feeling attenuated, stretched a bit thin, reverberating like a drumhead. So I headed for the meditation labyrinth behind the fire circle.

The thing I love about walking labyrinths is that I never know exactly how I'm going to get to where I'm going, or how the return journey will proceed. It's not like walking in a straight line, or even in a spiral from one point to the next. It goes this way, then that way. Doubles back on itself. Allows me to think that it's taking me to one place, and then does a bait-and-switch and suddenly I'm facing in the other direction.

Some of this, of course, stems from my practice of only looking a few steps ahead of where my feet are actually walking. If I stopped and scrutinized the labryinth, I could probably try to memorize its twists and turns. But that would defeat the purpose altogether. For me, a meditation labyrinth is about slowly walking and letting the journey unfold however it may. It's about the little surprises along the way. I know that I'm headed for the center of something beautiful; I know that when I leave the labyrinth I'll exit down the same forest path which brought me here. But between those two points I aspire to be open to surprises.

Some of this, of course, stems from my practice of only looking a few steps ahead of where my feet are actually walking. If I stopped and scrutinized the labryinth, I could probably try to memorize its twists and turns. But that would defeat the purpose altogether. For me, a meditation labyrinth is about slowly walking and letting the journey unfold however it may. It's about the little surprises along the way. I know that I'm headed for the center of something beautiful; I know that when I leave the labyrinth I'll exit down the same forest path which brought me here. But between those two points I aspire to be open to surprises.

If there is a better metaphor for this kind of "dialogue of the devout" (in Reb Zalman's terminology), I don't know what it is. Each of us came here prepared, on some level, to be challenged and to be surprised. I suspect that each of us also had some notion of where we thought we were going, where we thought our conversations would take us, what would be easy and what would be hard. And I'm willing to bet that the journey of these four days is bringing each of us to some surprises.

Once I reached the middle of the labyrinth, I thought, "ah, okay, now it'll take me back out again, that should be straightforward." And then the path went somewhere I didn't think it would go, and without my conscious volition my feet sped up. Wait. Was I confused? Had I taken a wrong turn somewhere? How could this possibly be the way toward the exit? And then I took a deep breath, got a grip on myself, and slowed my walking to my intentional and contemplative pace again. Of course I hadn't stepped "off the derech," off the path; the labyrinth just had a few final surprises in store for me before it returned me to the place of ingress/egress.

The real surprises always come when we think no surprises remain.

I wrote about walking a meditation labyrinth (and, for that matter, about Jewish-Muslim learning) at the ALEPH Kallah in 2011: Seeking and finding.

June 11, 2014

Morning zhikr on retreat

My cellphone sings me a gentle song at 4:30 in the morning and I roll out of bed.

My cellphone sings me a gentle song at 4:30 in the morning and I roll out of bed.

Ever since our son was born I have maintained that the 4am hour is the hardest time for me to be awake. When we used to have feedings at all hours, the 4am one was the one I dreaded. Earlier than that, and I could pretend that a night of sleep lay ahead; later than that, and I could tell myself that it was morning. But oh, I used to dread the hour between 4 and 5. Not today.

I find my way up the two flights of stairs to the Muslim prayer space. I join the women sitting in a circle on a spacious tapestry. And one of my new friends from this retreat explains that the leader of her Sufi order, Shaikh Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, settled on this arrangement of divine names and Qur'anic verses to be chanted in the morning at this hour.

Thankfully there are two copies of the little printed booklet which contains the words of the prayers -- one which our prayer-leader uses, and another which is offered to me. (The other Jew in the room has forgotten her glasses, so I don't feel guilty about monopolizing the transliteration and translation!)

Our leader offers the teaching from Bawa that one should seek with every breath to say a prayer asserting that there is nothing else but God. And I think: kol haneshamah tehallel Yah, "let every breath praise You." And I think of the meditation practice which maps the four letters of the Holiest Name onto every breath: before breathing, yud; inhale on heh; hold the breath vav; exhale on heh. And I think: ein od milvado, "there is nothing else but God." I think: our traditions have this in common.

And then the zhikr begins.

Zhikr (sometimes transliterated dhikr) means remembrance, as in remembrance of God. (I suspect the Arabic word shares a root with the Hebrew zecher, which also means remembrance.) It's a Sufi prayer practice. The last time I chanted zhikr was in 2011, at the ALEPH Kallah with Pir Ibrahim Farajajé and Rabba Deb Kolodny. That was in a Jewish setting; this morning I am profoundly aware that I am a guest, a visitor in someone else's prayer space and prayer context.

I remember the first time I had the experience of praying in a group of only women. I was struck by how our voices blended, how the timbre and tone merged together and our voices interwove like strands in a finely-braided cord. That's what this feels like, too.

We sing the fatiha, which is full of familiar words. We sing divine attributes: merciful, compassionate, forgiver. We sing in the name of God, the most merciful, the most compassionate.

We sing invocations of the angels Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, and I think: I invoke those angels every night when I bless our son before bed!

We sing blessings upon Adam, Noah, Abraham, David, Muhammad.

We sing verses from the Qur'an.

And then before the very last remembrances, my friend who is leading prayer -- we have connected with great joy around the fact that her teacher Bawa engaged in regular dialogue with my teacher Reb Zalman, and those dialogues (in printed form) are part of what the students of Bawa study even now -- my friend offers a prayer for those in need of healing, beginning with Reb Zalman, and my heart wells over.

I think of the story of Reb Zalman davening zhikr with the Sufis of Hebron, which has long been one of my inspirations; I think of his initiation into Inayati Sufism and eventual founding of the Inayati-Maimuni Tariqat of Sufi-Hasidim; and I know that he would be gladdened to see two of his students humbly learning from and with our Muslim hevre, study-friend-counterparts.

As we have been chanting, the sky outside the windows has changed color. Dawn has come.

When I leave the prayer space and tiptoe quietly downstairs, my heart is still singing.

June 10, 2014

Thank You, God, for making me a woman

It is morning at the Guest House, a beautiful retreat center which describes its mission as "[creating] opportunities for transformational work and [providing] a nurturing environment for those seeking to develop human potential and enrich the world." I walk down to the Jewish prayer space, a library with a few couches and shelves of books, where chairs have been arranged in a circle and a papercut mizrach (the word means "east" -- it's a piece of art denoting the direction of Jerusalem) leans against one wall. I enfold myself in my rainbow silk tallit and wrap my arm and head, my strength and consciousness, in tefillin. And then I sit down to pray.

I forgot to bring a printed siddur, but that's okay, because I have a digital one. I don't use it often, but I like having it on my tablet and on my phone -- makes it easy to daven wherever I am! But the digital siddur has a few quirks to which I am unaccustomed. One of them is that it features the most traditional version of every prayer text, and that in turn means that as I'm davening the birchot ha-shachar, the morning blessings, I bump smack into "Blessed are You, Adonai our God, Source of all being, Who has not made me a woman." (And, of course, its companion blessing intended for women to say -- "Who has made me according to Your will.") The siddurim I typically use don't include either of those. In their stead is a single version -- "Who has made me in Your image" -- appropriate for all to recite, regardless of sex or gender expression.

As I encounter these words this morning, I wonder how the Muslim women here would respond to them. Already, on our first evening together, the small group I was facilitating entered into a free-flowing conversation about what women are and aren't traditionally encouraged (or permitted) to do in our traditions. We talked about how people read us as religious women -- how do people respond to a woman wearing hijab? a woman wearing a kippah? What do people project on us based on those signifiers? How are those two religious identifiers similar, and how are they different? How do we respond, as religious women, to places where our traditions have encoded patriarchy as normative? I think I know what rueful smiles I would see on the faces of (most of) my Jewish colleagues if this blessing came up in conversation. I suspect that the Muslim women here would empathize.

I've written before about reclaiming (and rewriting) the "Who has not made me a woman" blessing -- as "Who has made me a woman!" -- during menstruation. I return to that practice almost every month, when I catch myself thinking disparaging thoughts. ("oy, is it really time for this again?") I use the blessing in those moments to remind myself that this female body is sacred and holy and that I am grateful for its many possibilities -- including its capacity to bear and nurture life. When I use that blessing at that time, it's aspirational. The words are meant to remind me to cherish the body I have, even when it's inconvenient. But the rest of the time, I tend to forget that that old line of prayer even exists.

This morning, though, here at this retreat for Jewish and Muslim emerging religious leaders -- a retreat which this year, for the first time, was conceived and created as an explicitly all-female space -- I am struck by the sheer ridiculousness of that classical line of blessing. I know its historical context. I can cite the reasons why its authors thought it was entirely reasonable to thank God for not having been born female. But this morning when it pops up on my iPad I daven a blessing of gratitude to God for having made me a woman, and today, a woman surrounded by an exquisite, creative, and powerful ad hoc community of other religious women. Damn right I'm grateful to be a woman! And grateful to be able to learn from, and with, this extraordinary group. How blessed I am.

June 6, 2014

Building bridges between Judaism and Islam

Several years ago, when I was still in rabbinic school, I participated in the first Retreat for Emerging Jewish and Muslim Religious Leaders, organized by RRC's office of multifaith initiatives. I blogged about the experience a bit as it was unfolding, and later wrote the essay Allah is the Light: Prayer in Ramadan / Elul, which was published in Zeek magazine. (Here's a short outtake from that essay.) Next week I will have the tremendous honor of participating in that retreat again -- this time as an alumna facilitator.

Several years ago, when I was still in rabbinic school, I participated in the first Retreat for Emerging Jewish and Muslim Religious Leaders, organized by RRC's office of multifaith initiatives. I blogged about the experience a bit as it was unfolding, and later wrote the essay Allah is the Light: Prayer in Ramadan / Elul, which was published in Zeek magazine. (Here's a short outtake from that essay.) Next week I will have the tremendous honor of participating in that retreat again -- this time as an alumna facilitator.

This year's retreat is for women only, which I think will shift the experience in fascinating ways. Our scholars will be Judith Plaskow (author of Standing Again at Sinai) and Aysha Hidayatullah (author of Feminist Edges of the Qur'an), and we will study the Sarah and Hagar story as it appears in our two traditions' holy texts. I'm responsible for facilitating the storytelling session one evening, and will offer a short workshop in writing spiritual poems / psalms for those who wish to partake.

I am so excited about doing this. Attending the first retreat of this kind back in 2009 was an amazing experience on many axes at once: meeting Jewish student clergy from across the many streams of Judaism, meeting an equally-diverse group of emerging Muslim leaders, studying texts together, breaking bread together, delving into the difficult conversations about what divides us, coming away with a stronger sense of what unites us and how our traditions can inform and enrich each other.

It's an honor to have the opportunity to help facilitate this experience for the women who will be attending next week's retreat. (And having read the participant bios, I'm eager to meet everyone who is taking part!) We've been asked to eschew our "devices" -- phones and computers and tablets -- as much as possible so that we can be wholly present to the retreat experience, so I may not be online much during the four days of the retreat program, but I look forward to coming home with stories to share.

Image from a post on the RRC Multifaith World blog.

June 4, 2014

On revelation

It is here that these classics come to life. They are not dry texts; they speak to us. Each is the opening voice of a conversation which we are invited to join -- a voice that expects reply. So in India we say that the meaning of the scriptures is only complete when this call is answered in the lives of men and women like you and me. Only then do we see what the scriptures mean here and now. -- Eknath Easwaran, Essence of the Upanishads

What then do we mean by revelation? Whether we understand the tale of Sinai as a historic event or as a metaphor for the collective religious experience of Israel, we have to ask this question. Revelation does not necessarily refer to the giving of a truth that we did not possess previously. On the contrary, the primary meaning of revelation means that our eyes are now opened, we are able to see that which had been true all along but was hidden from us. We see the same world that existed before the great religious experience, but now see it differently. The truth that God underlies reality, and always has, now becomes completely apparent...

Revelation, like Creation, is an eternal process. The real faith-question regarding revelation, like that of Creation, is not "Do you believe that it happened just that way, so many years ago?" It is rather, "Are you present to revelation here and now?" Are our inner eyes open to hearing the eternal message that calls out to us in every moment of existence? That message, the true essence of revelation, is Torah in its broadest sense, and its call may come through a great variety of channels. -- Rabbi Arthur Green, Ehyeh: A Kabbalah for Tomorrow

God is speaking on all 360 degrees; the question is, how do we open ourselves to the broadcast?

If I could hear all of the vibrations in this room -- cell phones, broadband, wifi, radio waves, microwaves -- I'd hear a jumble. If I can tune in to a particular frequency, I might hear something I could understand. God broadcasts on all frequencies; we need to adjust our radios to attune to God.

To connect with God, to log on to God, we need only awareness, because God is there all the time, making your heart beat.

I believe in progressive revelation. A metaphor: my first computer had 36k of memory. And I could do a lot with that. But some things, I couldn't do! Every generation adds more bytes. What we couldn't do individually, we can do collectively.

If we can't remember the revelation at Sinai, we need to recreate the memory. It's like experiential karaoke! The tradition is the music, and we reenact and recreate the words of the song. -- Reb Zalman (transcribed in 2004)

Happy Shavuot to all! May we each receive the revelation of Torah which we most need this year as our festival unfolds.

June 3, 2014

A psalm of gratitude for walking by the water

SEASIDE PSALM

For the asphalt which received my blue sandals.

For the homeowner who planted two palms

and a banana tree despite the latitude.

For the piles of broken seashells

at the base of the mailbox.

For robins puffing out their medaled chests

on manicured lawns

for the impromptu composition of birds

marking a melody on telephone wires

for the tabby cat resting beneath a rhododendron.

For sky blue as a freshly-pressed shirt

and Long Island Sound glinting in the sun.

For the homeowner's association

which allows pedestrian acess to land's edge.

For water splashing joyfully on the rocks.

For the smooth wooden bench of the gazebo

and the smell of salt in the air.

Even if my fingers tapped on my keyboard

the infinite clatter of pebbles dragged by the sea

I couldn't type enough of a thank you.

When I taught the master class on spiritual writing on City Island a few days ago, I asked everyone to write a paragraph about something for which they are grateful, using as many details and sensory descriptions as possible. Later in the morning, after many conversations about psalms and poems and words for God, we took fifteen minutes to draft psalms of gratitude, drawing on the raw material from the earlier generative exercise. I did the exercise and drafted a psalm along with everyone else. Here's what I wrote.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers