Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 153

July 7, 2014

Remembering my rebbe

How can I begin to write about Reb Zalman?

How can I begin to write about Reb Zalman?

So many others knew him longer than I did. And so many others have written, and will write, about how his extraordinary life and work have shaped Jewish life today. I only knew his work for the last twenty years; I only knew him in person for ten years. Many of his students, colleagues, and friends spent a lifetime with him.

Rabbi Arthur Waskow has written, "No one else in the 20th/ 21st century brought such new life, new thought, new joy, new depth, new breadth, new ecstasy, new groundedness, new quirkiness, into the Judaism he inherited –- and transformed." (Reb Zalman: His Light is Buried Like A Seed -- To Sprout.)

Rabbi Laura Duhan Kaplan has written, "Reb Zalman was an extraordinary individual who appeared at an extraordinary moment in time, and helped shape a response. In many ways, all of Judaism today is a renewed Judaism." (A Special Person at a Special Time: Reb Zalman's Jewish Renewal.)

Rabbi Jay Michaelson has written, "Hundreds of teachers, rabbis, cantors, and Jewish leaders found in Reb Zalman’s 'translation' of traditional Judaism into contemporary life a way to savor the blessings of Jewish life and practice, while consciously confronting those aspects of Jewish tradition which needed to be renewed — or discarded outright." (Reb Zalman, the Prophet of Both-And)

Other people have written about him wisely and well, is what I'm saying. But his teachings and his life have been so foundational to my sense of what Judaism is and can be -- I can't let his passing elapse without writing something here. Writing is how I remember, and I want to remember him. Have you ever been around someone who -- the moment you enter into their presence -- you can just feel that they really have it together, that they're tapped into something deep? Reb Zalman was one of those people.

I said last week that Reb Zalman is the reason I became a rabbi. And he is. I became a rabbi because I wanted to serve God and the Jewish people. But for many years I thought that was a yearning which would go unfulfilled. I found my teachers, my community, and ultimately my rabbinic lineage through Reb Zalman.

And I found Reb Zalman through Rodger Kamenetz.

And I found Reb Zalman through Rodger Kamenetz.

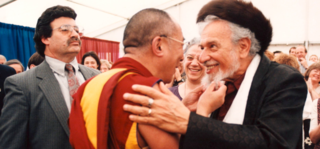

In 1994, my dear friend David (who is now soon to be ordained a rabbi himself) gave me a copy of Rodger Kamenetz's book The Jew in the Lotus. The story it tells is a true one: about the delegation of rabbis spanning the breadth of Judaism and Jewish practice who went together to Dharamsala, India to meet with the Dalai Lama and answer his question of how the Jewish poeple had survived 2000 years of Diaspora.

I remember reading that book -- I was in college at the time -- and being deeply moved by Rodger's descriptions of Reb Zalman. I remember in particular the scene where Reb Zalman goes to daven alongside Sikhs at prayer in their temple. Rodger writes:

Reb Zalman's spontaneous davening in a Sikh temple had placed him squarely on the side of total immersion dialogue. Explaining to me later, he quoted from the Psalms, "I am a friend to all who respect you, O Lord." The Sikh guru and he are "in the same business, struggling to see holy values don't get lost. I see every other practitioner as organically doing in his bailiwick what I am doing in mine. When a non-Jewish person affirms me, I feel strengthened in my work. When I affirm a non-Jewish person, he or she feels strengthened in their work." Zalman also cited Isaiah's prophecy, "My house shall be called a house of prayer for all nations."

...I was electrified by his joyous crossing of boundaries, his davening chutzpah. It broke through my own neat categories. I associated Orthodox practice with insularity. Yet here was Zalman, making contact with another religion by davening maariv.

I read that and I thought: holy wow -- his roots are so deep, and his wings are so broad.

Here's another scene from that book which moved me profoundly:

The morning [Reb Zalman] led the davening, he came up to me during the last part of the Shema, touched me on the shoulder, looked straight into my eyes, and said, "Your God is a true God." I found that a powerful challenge.

I usually felt as I prayed in a group that I was assenting to ideas and images that were very foreign to me or that I didn't have time to check out. Zalman's gesture had cut through that in a very personal way.... My God is a true God? Whch God was he talking about? Long white beard, old Daddy in the sky? Autocrat, general, father, king? Master of the Universe, doyen of regulations and punishments? These were the images that made me reject the very idea of God.

But in a funny mental jujitsu, the more I struggled with these images, the more what Zalman said came through. "Your God is a true God" meant to me that the images and the language weren't going to be supplied in advance. I would have to find them for myself out of my own experience....

I think of that scene every time I daven the words Adonai eloheichem emet, "your God is a true God." What does it mean to assert that my God is true? Perhaps that I am ready and willing to continue engaging with the tradition, with God, with our central stories and beliefs, in order to wrestle forth from all of those things a true relationship with the Holy One of Blessing. One way or another, Reb Zalman's challenge to Rodger continues to resonate in me.

And, of course, there's the chapter where the angel of the Jews meets on a high plane with the angel of Tibet. (If you've read the book, you know the one I mean. If you haven't, I won't spoil you -- it's worth reading in context. Trust me, this book is incredible.)

I reached the end of that book and I thought, "Wow, that rabbi sounds amazing. I didn't know you could be a rabbi like that." He was so clearly erudite, grounded, rooted in Jewish tradition (ordained by Chabad, for heaven's sake) -- and also equally clearly open to the unique wisdom available in other spiritual traditions. Around that time, when my then-boyfriend, now my husband, asked me to help him understand what I loved about Judaism -- what I dreamed Judaism could be; why I was attached to it; what I loved about it -- I lent him Judith Plaskow's Standing Again at Sinai and Rodger Kamenetz's The Jew in the Lotus. (It is a source of endless joy to me that I have now had the opportunity to get to know both Judith and Rodger!) Over the next several years I read what I could about, and by, Reb Zalman. His words and actions, in Rodger's book, had touched something deep in me.

I reached the end of that book and I thought, "Wow, that rabbi sounds amazing. I didn't know you could be a rabbi like that." He was so clearly erudite, grounded, rooted in Jewish tradition (ordained by Chabad, for heaven's sake) -- and also equally clearly open to the unique wisdom available in other spiritual traditions. Around that time, when my then-boyfriend, now my husband, asked me to help him understand what I loved about Judaism -- what I dreamed Judaism could be; why I was attached to it; what I loved about it -- I lent him Judith Plaskow's Standing Again at Sinai and Rodger Kamenetz's The Jew in the Lotus. (It is a source of endless joy to me that I have now had the opportunity to get to know both Judith and Rodger!) Over the next several years I read what I could about, and by, Reb Zalman. His words and actions, in Rodger's book, had touched something deep in me.

For personal reasons, in the years after college, I went through a period of painful alienation from Jewish community. What brought me back in? My first week at Elat Chayyim, the Jewish Renewal retreat center where I had my first living experiences of Jewish Renewal community, Jewish Renewal learning, and most importantly Jewish Renewal prayer.

For reasons I couldn't consciously explain, despite feeling distant from Jewish community, I signed up for a week-long retreat at Elat Chayyim with Reb Zalman. I'd come away from The Jew In The Lotus wondering whether this guy could possibly be as wonderful as Rodger made him sound. I needed to know whether he was for real. Unfortunately that summer he needed surgery and wasn't able to be at Elat Chayyim in person, but I'd already committed the money and planned to take a week there that summer, so I chose a different week-long retreat and took the plunge.

My first week at Elat Chayyim proved to me that there was more in Judaism than I had ever dreamed. I came home from that week and told Ethan that I had found my teachers -- that I wanted to become a rabbi someday like these people were rabbis. I learned that week that not only was Reb Zalman "for real," but he was part of an amazing community of teachers, learners, and fellow seekers. People who yearned as I yearned. People who had dedicated their lives to opening up the immeasurable treasures of Jewish tradition to we who were thirsty. Reb Zalman was in many ways the grandfather of Jewish Renewal -- and has left behind an amazing legacy of students, and their students, and their students, and generations of seekers and learners to come.

Reb Zalman on dialogue with Bishop Tutu, the Dalai Lama, and others: "What cosmology is needed to heal the planet?"

One of the things which drew me to Reb Zalman and to Jewish Renewal was what he called "deep ecumenism" -- not merely interfaith conversations on a surface or superficial level, but the need to enter into deep conversations with other people of faith, not only for our own sakes, but for God's sake, and for the sake of the planet:

I’d like us to enter into dialogue with devoutness, a dialogue of devoutness. There is a dialogue of theology, and that’s mostly futile. Why? Because it begins with what we should finish with. All theology is the afterthought of a believer. If we can’t get to the primary stuff of belief ...how do you get to the primary stuff of belief? By simply talking about how do you davven? If you show me your way that works for you I’ll show you mine and we can share. (From Deep Ecumenism, the transcript of a weeklong workshop taught at Elat Chayyim in 1998.)

He taught that every religion is an organ in the body of humanity -- that we need each one to be what it most uniquely is (after all, if the heart tried to do the liver's work, we'd be in trouble) and we also need each one to be in conversation and connection with the others (if the heart stopped speaking to the lungs, that wouldn't be so good either.) I've pointed many times before to the story of Reb Zalman among the Sufis of Hebron, which remains one of my favorite stories about him. I was drawn from the start to his post-triumphalism -- the knowledge that ours isn't the only legitimate path to the One.

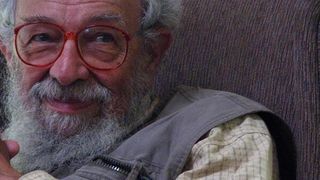

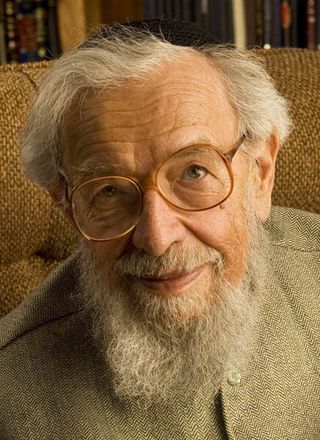

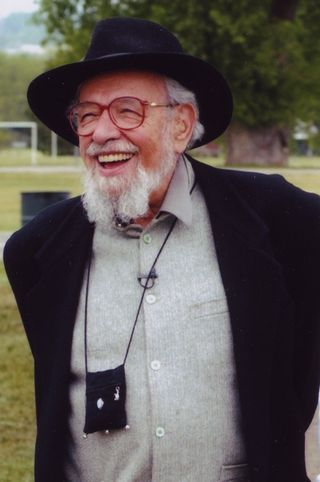

Reb Zalman could be very serious when the moment demanded, but he was frequently merry when he taught or when he led davenen. His eyes twinkled. He laughed a big beautiful belly laugh. He sang often while teaching -- lines of psalms or prayer, quotations, references, which were almost as likely to be in Arabic or Latin or Greek or Sanskrit as they were to be in Hebrew or Aramaic. He held an enormous wealth of kabbalistic and Hasidic teachings in his mind and was able to draw them forth and speak them in contemporary language, using metaphors which reached us where we are today.

Reb Zalman could be very serious when the moment demanded, but he was frequently merry when he taught or when he led davenen. His eyes twinkled. He laughed a big beautiful belly laugh. He sang often while teaching -- lines of psalms or prayer, quotations, references, which were almost as likely to be in Arabic or Latin or Greek or Sanskrit as they were to be in Hebrew or Aramaic. He held an enormous wealth of kabbalistic and Hasidic teachings in his mind and was able to draw them forth and speak them in contemporary language, using metaphors which reached us where we are today.

He loved computer metaphors. He used to say that his first computer had only 36k of memory, and what he can do now on his computer he couldn't have imagined then; just so, our increasing consciousness allows us to bring added holiness into the world in our generation. He taught us to think of the three words for "forgive us," which we recite over and over on Yom Kippur, as "drag the sins into the trash; empty the trash; and wipe the hard drive clean." I was always tickled when he pulled out science fiction metaphors, too. I remember hearing him teach about an imagined planet of two-headed beings; he used that story as a parable to explain the halakhic validity of counting those who are not men toward a minyan.

Or he would draw an analogy between how different religious traditions call on different names and faces of God, and "logging on" in different ways to the Cosmic life-source which we name as God. Our chants and prayers are the "password" which connect us with the Holy One of Blessing, and maybe our blessings connect us with this "port" and someone else's words connect them with that "port," but we're all connecting with the same One. And, he would point out, in the past we saw a difference between praying, e.g., in the name of the God of Israel or praying Bismillah ir rahman ir rahim (in the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate) or praying in Jesus' name. But that kind of triumphalism is no longer fruitful. As he wrote in "An Empathic Ecumenism:"

In the past every religious community wanted to make the deposit in the God-field only in their own name. They even saw it as a great combat in Heaven. Which religion is going to win? Which are going to be the victors in the religious sphere? It may have been necessary at one time in our development that we have such an attitude. But, today, this attitude just doesn't work. The question now is not who is going to be the champion of all religions, but how can we potentiate all the memory, all the energy, all the awareness, all the spirituality of all those forces in order to raise them?

The question isn't who's going to "win" -- it's how can we all bring our energy, our spiritual technologies, our hearts and souls, together in order to effectively transform the broken world? "The only way to get it together," he used to say, "is together."

Singing, Reb Zalman dons the Bnai Or rainbow tallit which he designed years ago.

He taught about paradigm shift, and saw the great events of the 20th century (from the horrors of the Shoah to the wonder of seeing Earth from space) as part of a new paradigm shift, a new turning. He taught about the importance of integral thinking, of seeking to build change which could both include and transcend what had come before. (This very much shapes the way Jewish Renewal rabbis think about halakha.) He taught us new (old) ways of entering deeply into prayer. The words of prayer, he taught us, are like a recipe book -- but in order to be sustained by the recipes, we have to enact them, to feel them in our hearts and souls.

In recent years he spoke to us frequently about how this "deployment" would someday end. I love that language: the sense that God had deployed his soul (indeed, has deployed all of our souls!) into this life to do particular work. He knew his time in this incarnation would not be forever. When he spoke to us in January at the OHALAH conference, he said:

It's such a wonderful trip that the Ribbono Shel Olam put me on. I can't tell you how grateful I am for the movie in which I acted in life! It is so amazing. And yet. Movies come to an end too...

When my tour of duty is over, the One who deployed me will find others to deploy.

I posted not long ago about about the book The December Project, by Sara Davidson, which consists of interviews with Reb Zalman about death and dying and end-of-life work, framed by her experiences and her skepticism and her transformation. If you never had the blessing of being able to learn directly with Reb Zalman, this book is one way to get a glimpse of how he spoke. Another way, of course, is to dip into some of the wealth of material on YouTube. I am already finding sustenance in watching short YouTube videos -- hearing his voice, seeing the sparkle in his eye, remembering that his teachings are alive even though his body has reached its rest. (I can also recommend his books -- I frequently lend out my copy of Jewish With Feeling, and his recent book Davening: a Guide to Meaningful Jewish Prayer is terrific, and oh, his new edition of Psalms in a translation for praying...!)

He taught me to talk not about God but to God -- which has deeply informed not only my prayer life but also the way I'm trying to teach our son about God. At OHALAH in January he remarked:

When I drive, I have a sense that the Ribbono Shel Olam in blue jeans is sitting in the passenger seat and I can just talk. Even that kind of thing, having a daily conversation with the holy Shekhinah in that way, is what keeps you on track...

I can't tell you how often I have followed his example and spoken with God while driving alone on a quiet country road, or how frequently that practice has opened my heart and sustained me.

The last time he and I spoke was some months ago when I shared a post I'd been working on for a long time -- about taharah before cremation. Once the post was online, I sent an email about it to the listserv for OHALAH, the association of Jewish Renewal clergy. Within an hour of my sending it, I got a call from Reb Zalman. "Reb Rachel lebn," he said, "I want to talk with you about what you've written." And we talked, and he clarified some things about his own thinking, and later that day I added an addendum to the post. He was actively engaged with thinking and teaching until the very end of his life -- he had just completed a Shavuot retreat at Isabella Freedman a few weeks ago when he fell ill and was hospitalized.

I am even more grateful now that I took our infant son to a Shavuot retreat with Reb Zalman at Isabella Freedman the spring before I received smicha -- and that I was privileged to hear in person the Torah he gave over at 4am that night, the last and most intense teaching of the tikkun which led us to the dawn. Someday I will be able to tell our son, "You don't remember this, but your first Shavuot, I took you to a retreat with my rebbe, and it was amazing."

I find myself thinking now about something else he said at OHALAH a few months ago: even as he was reminding us to hold fast to those things which are foundational and should not be changed, he also urged us to continue innovating and exploring. That was Reb Zalman in a nutshell: deeply rooted in the soil of our tradition, and also stretching branches out toward the highest heavens. He said:

Ours is the beta version of what klal Yisrael needs. And in a beta version, not everything that's being tried is going to be finally adopted! But we have to continue to experiment, to experience, so that the things that come from the past, we can see how can they be updated and shaped. In this way the past can serve us in the present and in the future.

And when we realize that there are certain things that cannot be updated, and we open ourselves to the Ruach haKodesh and ask ourselves what the future needs, then we learn to see in the present what we need to create.

That kind of openness is what led him to playfully experiment with so many different things: from recorded prayers designed to be heard on a walkman so that Hebrew would flow into one ear and English into the other, to bringing ancient Jewish meditation practices to the forefront of modern Jewish life, to workshops in "davenology," to chanting English translations of Torah and haftarah to the ancient melodies of trope, symbolic rainbow-striped tallitot, calling people to the Torah in group aliyot and giving group blessings, eco-kashrut, and countless other ideas and innovations which have shaped Jewish life today across the denominations. As his official ALEPH obituary notes, "Where others saw walls, he saw doors."

When I learned that Reb Zalman's soul had left this earthly plane, I was at the synagogue preparing for Shabbat. One of my congregants, who was here that afternoon and saw me weeping, left a card for me on my desk. "How blessed we are if, in our lifetime, we meet someone whose guiding light leads us where we are meant to go," she wrote. I am blessed indeed.

What makes a rebbe? One traditional answer is that "A rabbi answers questions; a rebbe answers people. A rabbi hears what you say with your mouth; a rebbe hears what you say with your soul." Reb Zalman taught that "rebbe" is a role -- not a specific person, necessarily, but a way of relating. He taught that we can be rebbeim for each other, that we can consciously choose to move in and out of the rebbe role. "Everyone should, for time to time, get the chance to sit in the master's chair," he said in 2013. "Just so that they can get attuned to what happens when you reach up and say, dear God, what would you like me to share with these people? And to see what comes; it's very beautiful, very holy." He used to do an actual exercise where everyone would sit at the table, with him in the rebbe's chair at the head, and he would offer a teaching -- and then instruct everyone to rise and shift over one chair, and whoever had moved into the rebbe's chair would have the opportunity to be in that role for a little while. (In retrospect I see in that teaching yet another gentle way of reminding us that his deployment wouldn't be forever.)

It seems to me that a rebbe is not only a pastoral caregiver but a spiritual conduit. The Zohar, a foundational work of Jewish mysticism, refers to Moses as the raaya meheimna of Israel -- a phrase which can be translated both as "faithful shepherd" and "shepherd of faith." A rebbe, like Moses, not only cares for his flock, but serves as a conduit for our faith, connecting us with God. The rebbe is never the object of that faith, the endpoint of the faith -- God forbid we should worship a rebbe, even a great one! Rather, the rebbe opens the door and helps us connect with God. She is not the moon, but the finger pointing to the moon.

It is said of Moshe Rabbenu, Moses our Teacher, that "never again will there arise a prophet like Moshe." And indeed there will not. Moshe led the people out of Egypt and into a new reality. Moshe spoke directly to God, face-to-face. And there are ways in which Reb Zalman feels to me like a Moshe -- irreducible, irreplaceable. There will never be another one like him. No one will ever bridge between pre-Shoah Europe and postmodern America, between deep Hasidic immersion and far-flung spiritual influences, between kabbalah and Sufism and Native American shamanistic practice and Buddhism and integral theory and transpersonal psychology and Gaia theory and computer metaphors, the way that he did. Never again will there arise a teacher like Reb Zalman.

And at the same time, I think back to a Hasidic story I heard Reb Zalman tell many times, about the hasid who inherited his father's Hasidic dynasty and promptly began doing things differently than his father had done. His followers complained, but he countered that he was doing precisely what his father had done -- "my father was the rebbe in the way his heart called him to be, and I am the rebbe in the way my heart calls me to be."

There will never be another Reb Zalman, but I hope that all of us who are his students, and the students of his students, and the students of his students of his students, will follow in his footsteps -- not by mimicking his life and practice but by living out Jewish Renewal in the ways our hearts and souls call us to do, and the ways we perceive the Holy One is calling us to do. By serving the Holy One of Blessing as only we can. By doing the work of healing and bridge-building for which our souls were deployed in this world. That's how we can honor his memory. And I feel certain that somewhere, somehow, in some ineffable way that I can't intellectually understand, he is smiling at us still, and singing with us, and shepping naches to see us continuing the work of renewing Judaism and healing our earth.

Some of the other posts I've found meaningful:

Rabbi Zalman Shachter-Shalomi - Jewish, With Feeling (Rabbi Shulamit Thiede) "Reb Zalman reached out to the disaffected, to the secular Jew, the alienated Jew, to any Jew. You only needed to stop for a moment and he could hold you with a story – each blessed with an unforgettable punch line that always, inevitably, elicited a smile, outright laughter, a nod, or a tear. // This morning I told a friend, 'He gave something to everyone.'"

Rest in Peace Reb Zalman: My Rebbe Died Today (Amichai Lau-Lavie) "[T]he sacred master, holy fool, kindest soul, fierce teacher, visionary founding father and leader of the Jewish Renewal movement, the holy spark responsible for countless souls on fire all over the world, for a global spiritual revolution, for the revival of a Judaism that matters to the body, earth, soul and mind, the genius whose prophecy of paradigm shift was and still is ahead of its time – died in his sleep today, at 89 years old...Few could straddle the authentic hasidic and mystical path along with true devotion to the soul of the planet, and to every sacred path. None did it with such elegance and depth and grace."

Reb Zalman Married Counterculture to Hasidic Judaism (Shaul Magid) "Not since Mordecai Kaplan’s founding of the Reconstructionist movement has an American Jewish spiritual leader offered as detailed and as systematic a vision for Judaism in the twentieth century. Part of Schachter-Shalomi’s project is founded on his belief that exploring the untapped commonalities between religious traditions and spiritual practices would both enhance Judaism and move human civilization further toward overcoming oppositional barriers..."

On the Death of Zalman Schachter Shalomi, z’l: A Great Jewish Teacher and the Founder of the Jewish Renewal Movement (Rabbi Michael Lerner) "Rabbi Zalman Schachter Shalomi, founder of the Jewish Renewal movement, [was] one of the most creative and impactful Jewish theologians of the last forty years... I write with tears in my eyes and love in my heart for this incredible teacher, a source of inspiration for literally hundreds of thousands. I loved this man very very deeply for the past fifty one years that I knew him... What was most amazing about Zalman was that he continued to grow throughout his life both intellectually and spiritually."

Laying Our Rebbe to Rest (Rabbi Marc Soloway) "So many of us feel like we are among the mourners in this loss...I think the thousands and thousands of people who have been touched by Reb Zalman each carry their own piece, their own story, their own holy sparks of this great man. My hope and prayer is that we can and will each make manifest these holy shards, so that Reb Zalman’s light continues to shine in this dark world and that we, collectively, can continue his paradigm-shifting work of inspiring and lifting up souls."

My mentor, my teacher, dear friend (Rabbi Art Green) "Our lives were dedicated to the very same question: How do we take this mystical Judaism we both love and make it alive and vital for the current era? Zalman was driven by that question, knowing how rich and deep the sources of that teaching are, and how alien and difficult their original garb is for those we teach. What should we keep of that tradition? What should we adapt? What should we lovingly leave behind? How do we figure out that balance, not “losing the baby with the bathwater,” as it were? We both have given our lives to that search. //...Zalman was my model of the contemporary Jewish seeker. That model means both feet firmly planted in the tradition; both eyes wide open to what’s happening in the world, both today and in anticipated tomorrow. Zalman PIONEERED this path; I was privileged to follow it, in my own way."

Fifty Year Tribute, Passed but Present (Morah Yehudis Fishman) "In one recent class, he referred to the movie, Her, and especially the line that the man says to his living computer- ‘Are you as intimate with anyone else as with me?’ And the answer came back- ‘multitudes.’ Reb Zalman said that’s the way it is with G-d. And I would like to add, that’s the way it was with Reb Zalman. So many people, men women, and children-here and around the world felt that hug of intimacy from Reb Zalman as if you were his ‘one and only love.’ And each of us was, because his heart was bigger than this whole world, and will continue to embrace us from wherever he is."

Obituary posted by Miles Netanel-Yepez, one of his dear collaborators: Rabbi Zalman Shachter-Shalomi, Father of Jewish Renewal, Dies at 89. It's an extraordinary obit, which explores (among other things) his legacy within Jewish Renewal, how he reached spiritual seekers who had been disaffected from Judaism, and his longtime friendship with spiritual leaders such as Thomas Merton and the Dalai Lama. Also don't miss the recent exhibit curated by the University of Colorado: Reb Zalman and the Origins of Post-Holocaust American Judaism.

Memorial contributions may be made to ALEPH's Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi Endowment for Jewish Renewal. Please give generously in his memory and to help sustain his legacy.

July 4, 2014

Fourth of July: not a yontif, but still has meaning

Ten years ago when I first heard Reb Zalman (zichrono livracha / may his memory be a blessing!) teach in person, he sighed that the Fourth of July had once been an important yontif (holiday), but seemed no longer to be so for many American Jews. He was talking about how certain ideas don't necessarily hold the power for us that they did in earlier eras. (For instance, "King" used to work well as a metaphor for God, but today it doesn't have the resonance it used to, so we've needed to find different partzufim, different "faces" of God, to which we can better relate.)

Ten years ago when I first heard Reb Zalman (zichrono livracha / may his memory be a blessing!) teach in person, he sighed that the Fourth of July had once been an important yontif (holiday), but seemed no longer to be so for many American Jews. He was talking about how certain ideas don't necessarily hold the power for us that they did in earlier eras. (For instance, "King" used to work well as a metaphor for God, but today it doesn't have the resonance it used to, so we've needed to find different partzufim, different "faces" of God, to which we can better relate.)

I suspect that when Reb Zalman was a young man it was easier than it is today to feel unambiguous patriotism. That may have been especially true for Jews who came here in the wake of the Shoah and saw America as the goldene medina, the golden land of opportunity and freedom where it was safe to be a Jew and where anyone could succeed. Certainly that was true for Reb Zalman, as it was true for my grandparents -- all of whom escaped wartorn Europe, all of whom lost loved ones in the Shoah, all of whom found new opportunity in this land.

In my generation, at this moment in time, patriotism can be a complicated thing. Many of us have mixed feelings about our government and its actions, regardless of which party is in power. We're increasingly aware of how our nation's exercise of power around the world can be problematic. We're also increasingly aware of systemic racism and injustice -- places where our nation hasn't lived up to our hopes.

I love many things about this country; I love many places in this country; I love many of the ideals of this country. But I don't love everything that this national entity does. And patriotism seems inextricably linked with nationalism, and nationalism has led to a lot of suffering around the world in recent history. As Lee Weissman tweeted a few days ago:

The simple cure for Nationalism should be a decent high school course in Modern European history.

— Lee Weissman (@JihadiJew) July 2, 2014

It seems to me that nationalism played a role in both World War I and World War II. (Certainly German nationalism was one of the forces which fed into Hitler's ascent to power and the horrors of the Shoah and the deaths of millions.) Nationalism played a role in the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, in which at least a million people were killed and some 12-14 million people were displaced. And I think nationalism plays a role in the continuing conflict in Israel and Palestine.

In our household we talk a lot about cosmopolitanism, embracing the notion of being a citizen of the world in all of its interconnectedness. Here's how my husband Ethan described cosmopolitanism in an interview with Henry Jenkins:

[Kwame] Appiah, a Ghanaian-American philosopher, suggests that cosmopolitans recognize that there is more than one acceptable way to live in the world, and that we may have obligations to people who live in very different ways than we do. This, he argues, is one of the possible responses to a world where we find ourselves interacting with people from very different backgrounds. Cosmopolitanism doesn’t demand that we accept all ways of living in the world as equally admirable – he works hard to draw a line between cosmopolitanism and moral relativism – but does demand that we steer away from a fundamentalist or nationalist response that sees our way as the only way and those who believe something different as inferior or unworthy of our consideration or aid.

(Read the whole interview at Henry Jenkins' blog. And hey, while you're at it, read Ethan's award-winning book Digital Cosmopolitans: Why We Think the Internet Connects Us, Why It Doesn't, And How To Rewire It.)

What does one do with all of these feelings on the Fourth of July?

For me, the glorious Fourth feels a little bit like the tailgate party outside a Green Bay Packers game. Does that sound sacreligious? I suppose that's evidence for Reb Zalman's theory that for many Jews today, Independence Day is less a yontif than it was for our forebears. But I don't mean it as a knock on the day. It's great to celebrate one's team and the community which has arisen around that team -- as long as one doesn't fall into the fallacy of imagining that people who support a different team are inferior.

How will we celebrate the Fourth? Weather permitting, we'll go to the sweet little parade in a nearby town. Everyone will be wearing red, white, and blue. There will be bunting and streamers and balloons galore. There will be a marching band, and kids on tricycles, and people riding in classic convertibles throwing candy. Everyone will cheer. Then my family will go to the synagogue picnic, where little kids will splash in a kiddie pool, and adults will grill hot dogs and hamburgers, and we'll eat watermelon and popsicles. Then, after the kids are put to bed, we'll sit on our deck and watch distant fireworks across the valley.

It feels great to celebrate community. But at the end of the day, just as I know that there are other teams in the NFL besides the Packers for whom one might reasonably root, I know that my community -- this nation -- isn't the only wonderful one in the world. I know that our customs and contexts aren't the only way to live. (They're not even the only good way to live. Those who've been fortunate enough to live in, or even to visit, more than one country get a sense for how norms and customs differ, without any one set being the "right" ones -- that's part of why travel is so wonderfully broadening.) And that's okay. I don't need my country to be the "best place on earth" -- I just need it to be the best version of itself that it can be.

I want to live in an America which lives up to the ideals I hold dear. Some of those ideals were built into the fabric of its founding (equality, rights, liberty and justice for all.) Others have arisen in recent decades as humanity as a whole has become more enlightened (equal rights for women and for people of all races, equal marriage rights, equal rights for GLBTQIA folks, and so on.) When I think about the positive valances of patriotism, I think of those ideals. I think of times when I've felt hope that this country could be a better place, a kinder place, a more just and righteous place. That's what I'd like to be cultivating today.

Some months ago a friend and I went to the Williams College Museum of Art to see, among other things, original copies of some of America's founding documents. I felt a frisson of awe looking at that looping old handwriting, the paper so fragile but the words so enduring. "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men [sic] are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness..." I admire the idealism and the optimism with which those words are imbued.

Is today a yontif, a holy day, for me? Not exactly. But it is a day for pausing to celebrate where we are, before we pick up our tools again and continue the work of -- in the words of our Constitution's Preamble -- trying to "form a more perfect Union." Happy Fourth of July to all who celebrate.

Related: the poem Not There Yet. "When Moshiach comes / everyone will celebrate / interdependence day..."

July 3, 2014

May his light continue to shine

My beloved teacher, rebbe, and zaide ("grandfather") Rabbi Zalman Shachter-Shalomi, z"l (may his memory be a blessing) died this morning in his sleep. He was 89.

Here is a seven-minute video in which he explains and explores psalm 23 -- which seems like a fitting way both to remember his vitality, his laughter, and his wisdom, and also to ease the hearts of those who grieve.

I'll write more about him later. Right now I have only tears and gratitude.

Reb Zalman is the reason I became a rabbi. That's a longer story; maybe I'll tell it next week. For now, I am so endlessly grateful to have known him, to have learned from him, and to be a part of his rabbinic lineage.

May all who mourn his passing -- most especially his widow Eve, his many children and grandchildren, his students and the students of his students -- be comforted. זכרונו לברך –– may his memory be a blessing.

Memorial contributions may be made to ALEPH's Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi Endowment for Jewish Renewal.

A prayer in remembrance

by Rabbi Rachel Barenblat and Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb

May the memories of our boys

killed in senseless hatred

be for a blessing.

May their spirits be lifted up

and comforted in the close embrace

of God's motherly presence.

May our precious children be safe from harm.

May all the children be our children.

May we protect all parents from mourning.

May our hearts and the hearts of our people

be healed quickly in our day

from the wounds of the past and present.

May every grieving parent find comfort.

May we live to see the day

when no parent has to grieve.

We'll read this prayer at my congregation on Shabbat morning before mourner's kaddish. If it speaks to you, you are welcome to share it with your community, though please take care to keep authors' names attached. May the families of Naftali Fraenkel, Gilad Sha'ar, Eyal Yifrah, and Muhammad Hussein Abu Khdeir be comforted.

A poem about night waking

WAKING

I will wake in the morning -- will my breath remember me, will my spirit be returned back from the rooms' shell, caverns echoing and empty?

-- Seon Joon, "the quiet"

Because You grant it

I will emerge from sleep

not once but twice tonight

my spirit returning

to alight in this body

like a small butterfly

as I shuffle yawning

across warped floorboards

until my feet reach cool tile

and half-asleep

bless miraculous

tubes and openings

if one were to be closed

where it should be open

-- another clot to the brain

this time maybe

not so gentle. But so far

so good: the body's working

and when dawn comes

my soul, my breath

will be restored to me

for another day

of offering praise.

You have faith in me.

This poem was inspired by a line from Seon Joon's post the quiet, which was in turn inspired by a poem by Luisa A. Igloria.

On "miraculous / tubes and openings..." see Morning blessings for body and soul (2007) and Sanctifying the body (2005.)

On "another clot to the brain," see One year stroke-free (2007.)

On "my soul, my breath / will be restored to me," see One from the archives: morning blessing poem cycle (2012). (Some of those poems will appear in my next collection, Open My Lips, forthcoming from Ben Yehuda Press -- stay tuned.) Also see On gratitude and thanks: a sermon for the UU community of Montréal (2013.)

July 1, 2014

Not everyone can carry the weight of the world

A while back I ran across a quotation from Audre Lorde which really struck me, so I copied it into the to-do list file which is always open on my computer, as a reminder that self-care is always on the to-do list. Lorde wrote:

A while back I ran across a quotation from Audre Lorde which really struck me, so I copied it into the to-do list file which is always open on my computer, as a reminder that self-care is always on the to-do list. Lorde wrote:

"Caring for myself is not self-indulgence;

it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare."

Our world tells us, in myriad subtle and unsubtle ways, that taking care of ourselves is self-indulgent and that we should be focusing our energies on more important things. (This message is, I think, most insidiously communicated to women, particularly mothers -- though I'm sure that men and non-parents hear it too.) But I believe Lorde is right: taking care of oneself is an act of self-preservation, and because that act flies in the face of every voice which would argue that we're not important, it's an act of profound defiance.

You are important. You, reading this right now. Regardless of your gender or race or class or faith, regardless of whether you are healthy or sick, whether you are able-bodied or disabled, no matter who you are and where you come from -- you matter. And your wellbeing matters. In (Jewish) theological language, I would say that you are made b'tzelem Elohim, in the image of God. Your soul is a spark of light from the Source of all light. And that makes you holy and worthy of care, as are we all.

I'm going to assume for the moment that you agree with me that self-care is valuable and that each of us is deserving of care. So far, so good. But what does it mean to care for oneself online? In the offline world it's relatively easy to discern ways of taking care of oneself: get enough sleep, exercise, perhaps treat oneself (budget permitting) to an iced coffee or a manicure -- we all know our preferred modes of self-care. But how do we practice responsible self-care online?

I'm not entirely certain what online self-care entails, but I'm pretty sure that one piece of that puzzle is being mindful in where we go, online, and what kinds of conversations we have when we're there. The things we read, the news we consume, the conversations in which we engage: all of these have an impact. They impact us in all four worlds: not only intellectually, but also emotionally, spiritually, even physically in our bodies. And there's a lot of tough news in the world right now.

Maybe for you it's news about the Facebook research on "emotional contagion." (Lab rats one and all: that unsettling Facebook experiment.) Or the recent Supreme Court decisions. (I feel sick: liberal pundits react to Hobby Lobby ruling.) Or the deaths of Gilad Shaar, Naftali Frankel, and Eyal Yifrach. (We should all be ripping our clothes in mourning.) Or the death of Yousef Abu Zagha. (What was Yousef Abu Zagha's favorite song?) Or something else I haven't mentioned -- there's always something else.

One way or another, our social media spaces -- our virtual public square -- are the places where we connect. And as Facebook's "emotional contagion" research showed --and I suspect most of us knew this intuitively -- the things we hear from the people around us have a measurable impact on how we ourselves feel. (As Charlie Brooker quipped in the Guardian, "Emotional contagion is what we used to call 'empathy.'") When people are expressing joy and celebration, our hearts incline in that direction too. And when people are expressing grief, anxiety, sorrow, pain, our hearts incline in those directions instead.

That our hearts feel a pull toward the emotions expressed by other people in our lives is a fact of human nature, and on balance I think it's a good thing. But the internet facilitates more kinds of connections, between larger networks of people, than used to be part of ordinary human existence. Many of us check in with social media many times daily. Maybe you keep Twitter open in another browser tab, or check Facebook on your phone while standing in the check-out line at the drugstore. This can be a tremendous boon -- I remember nursing our infant son in the middle of the night and reading updates from friends on my phone, and feeling incredibly grateful that I could be connected with their lives even when my own life felt so isolating.

But sometimes our interconnection can become enmeshment. And at times of tragedy or crisis, it's easy to get caught-up in online conversations which aren't actually healthy. Pause and notice how you're feeling when you're navigating your online world. Make an active decision about whether your online spaces are helping you feel connected, or whether they're contributing to feelings of alienation or overwhelm. Different people can handle anger, anxiety, and grief to differing degrees. And any single person will be able to handle different levels of these emotions at different times in their life, depending on what else they may be carrying.

Maybe you're usually able to handle a lot of negativity around a given issue, but right now you're worried about a sick family member, and as a result your heart feels more exposed, which means you're experiencing everyone else's sorrow more deeply, so reading Twitter has you near tears. Maybe you're usually untroubled by confronting other people's anxiety, but today you're finding that your own fears are triggered by what you're reading, and watching friends argue on Facebook is making your chest feel clenched and tight.

If being in your usual online spaces is giving you more anxiety, or more grief, or more anger than you can comfortably manage, give yourself permission to step away. (Or if you need permission from outside yourself, consider it rabbinically granted!) Keeping up with every latest update -- every news bulletin, every blog post, every Tweet and status update -- may help us feel informed, but it doesn't necessarily help us emotionally or spiritually. Guard your own boundaries however you need to do.

It's okay to step away from certain parts of the internet, or to deflect certain dinner table conversations, in order to maintain your equilibrium. And if someone in your life needs to step away from something, give them the benefit of the doubt. We never know what the other people in our lives are dealing with. (We especially never know what other people on the internet are dealing with.) No one can be responsible for taking care of everyone's emotional and spiritual needs, but each of us can be responsible for her own.

This post's title is borrowed from an REM song.

I also commend to you Beth Adams' A plea against anxiety.

Moments

There is only one of me; I can only be in one place at one time. And yet my job calls me to inhabit several moments in time simultaneously. This is the nature of rabbinic work.

There is only one of me; I can only be in one place at one time. And yet my job calls me to inhabit several moments in time simultaneously. This is the nature of rabbinic work.

On the one hand: today. This is the day that God has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it! I offer a morning prayer for gratitude, I open up my calendar, I scan to see with whom I am meeting today and what is on my to-do list.

On the other hand: Shabbat. I study this week's Torah portion, I prepare verses to read from the scroll, I think about songs and prayers. I pick up my guitar and my fingers automatically go to the chords for our Shabbat melodies.

On yet another hand: the Days of Awe. Now the machzor is released into the world, and I'm having weekly Skype dates with our student cantor. Every time he sings a line of high holiday nusach, the holidays come rushing in around me like waves.

On another hand still: a funeral which took place many months ago, and the ritual unveiling of the headstone which will take place some months hence. A "then" which is past, and a "then" which hasn't happened yet.

I remember preparing the eulogy for that funeral. I remember standing on the cold winter earth. I imagine what it will feel like to return to that spot with the family to dedicate the stone which marks that spot, which memorializes that life.

One of the names for God which we most frequently use is מלך העולם, melech ha'olam, usually translated as "king of the world" or "sovereign of the universe." But the word olam can mean both space and time (as in l'olam va'ed, "for ever and ever.")

My son sometimes asks me at bedtime where God is, and I tell him that God is everywhere. ("But invisible," my son prompts, and I confirm that yes, he's got that right.) God is also everywhen -- present in every moment. Past, present, and future all at once.

It's my job to be in this moment -- if I am sitting with a congregant for a pastoral conversation, they deserve my full presence. And also to be in that moment, and that other moment -- remembering what has come before; anticipating what's yet to come.

June 29, 2014

A day in the sun

An afternoon at a friend's house. The scent of sunscreen, the feel of water lapping against my body, the excited squeals of several little boys wearing floaties and splashing around the pool clutching pool noodles and kickboards emblazoned with superheroes.

In between swishing our kids through the water in giggly circles, the adults talk about books we've been reading, about the local college (from which many in this circle of friends graduated, and where others among us now teach), about summer memories.

I remember chlorinated swimming pools, and fingers wrinkled pruny from spending all day there. The rub of the diving board beneath my tender toes. Sunwarmed bricks at the edge of the pool. Night swimming, lit by one underwater light.

I remember the warm waters of Lake McQueeney and the gentle Guadalupe which feeds into it. I remember floating in an inner tube down the river, or leaping from the back of a boat in a lifevest and skis, letting rough woven rope play through my hands.

And I remember basking like a contented lizard in the south Texas sun, lying on a woven chaise and listening to Ottmar Liebert or k.d. lang as sweat dripped down my nose, holding out as long as I could before diving into the pool and exulting in the cool splash.

In between swimming this afternoon we pause to eat cold crisp cubes of watermelon and fresh local strawberries warm from the sun. I wonder what this group of little boys will remember about this ordinary, extraordinary summer day when they are grown.

June 27, 2014

Confronting Jewish privilege at the Jewish-Muslim emerging leaders retreat

“If you have parents who went to college, take a step forward.”

“If when you walk into a store, the workers sometimes suspect you are going to steal something because of your race, take one step back.”

“If you see people who share your identity reflected on television and in movies in roles you don’t consider degrading, take a step forward.”

When we began the exercise, we were standing in a row, holding hands. Our facilitators took turns reading a series of statements: if this is true for you, step this way. If that is true for you, step that way. It wasn’t long before our chain of hands was broken.

Before this session, I would have said I was aware of my privilege as a white, affluent, college-educated, Jewish cis-gender woman. I’ve read White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. But it turned out that I wasn’t nearly as aware of privilege as I had thought.

In Jewish Renewal we speak often in the paradigm of the “four worlds”, of assiyah (physicality), yetzirah (emotion), briyah (thought) and atzilut (spirit/essence). In briyah, the world of intellect, I think I did have a handle on my own privilege. But when I had the physical experience of having to let go of the hands of my friends, and of seeing at the end where each of us was positioned, the realities impacted me in the emotional and spiritual realms, and they hit me hard.

This exercise, often called The Privilege Walk, was part of our session on “Challenges in Jewish-Muslim Engagement” at a wonderful retreat for Jewish and Muslim emerging religious leaders, held this month in Chester, Connecticut, and organized by the Reconstructionist Rabbinic College’s department of multifaith initiatives...

Read my whole essay at Zeek: New Depths in Jewish-Muslim Dialogue: Jewish Privilege.

Deep thanks to RRC and to the Henry Luce Foundation for making the retreat possible, and to my Jewish and Muslim sisters who attended, facilitated, and taught at the retreat.

Shabbat shalom and chodesh Tamuz tov to my Jewish readers; to my Muslim readers, Ramadan Mubarak!

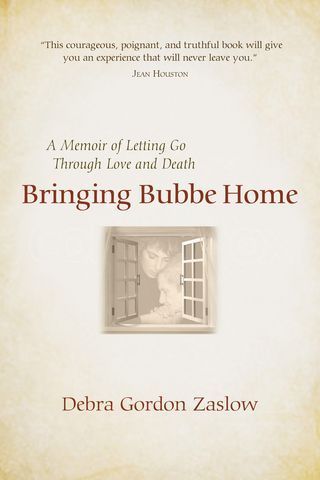

Debra Zaslow's Bringing Bubbe Home

Several years ago, at an ALEPH Kallah in California, I was blessed to take a week-long sacred storytelling class taught by master storyteller Debra (a.k.a. Dvorah) Zaslow. The class was wonderful, not least because Dvorah's way of telling stories, and teaching the telling of stories, goes straight to the heart. So when I heard that she had a new book out -- Bringing Bubbe Home: A Memoir of Letting Go Through Love and Death (White Cloud Press, 2014) -- I knew I wanted to read it.

Here's a video trailer for the book:

"Seventeen years ago I was immersed in my life as a professional storyteller, wife of a rabbi, and mother of two teenagers when I felt compelled to bring my 103 year-old grandmother, Bubbe, who was dying alone in a nursing facility, home to live and die with my family. I had no idea if I'd have the emotional stamina to midwife her to the other side."

The story unfolds with slow inexorability. There is nothing easy about bringing an elderly relative home to die, and this slim but powerful memoir doesn't gloss over the hard parts. And yet once I started reading, I didn't want to stop; I wanted to know how it would unfold. It's not exactly that I wanted to "know what happens next" -- obviously the book was going to lead to death, the end of every human story since time immemorial. But I wanted to see how it would happen, and how Dvorah and her family would get there, and what blessings might be there for the finding.

The book is beautifully-written. I found myself particularly moved by passages where Dvorah was reflecting on what she was doing and why:

The book is beautifully-written. I found myself particularly moved by passages where Dvorah was reflecting on what she was doing and why:

Below us the metal rails of Bubbe’s new bed gleam. I don’t stop to think that maybe I’m bringing Bubbe here because I couldn’t be with my mother at her death. I can’t really see the hole in my heart or hear my mother’s voice. Bubbe’s voice is all I hear, as if she’s calling from under deep water. I’m answering her, ready or not.

Her descriptions of caring for her Bubbe, even with caregivers employed around the clock, remind me of the sometimes bleak exhaustion of caring for a newborn. It's an obvious comparison, of course, and it's one which Dvorah makes, too:

Each morning I descend the stairs to Bubbe’s room and come up for air at bedtime. It’s lucky if I can sneak upstairs for a shower, and if I find time to go out, I’m too exhausted to speak to anyone. Apparently I’ve forgotten how to say anything interesting anyway, so it’s better that I keep my mouth shut. Again, this is very much like new motherhood, but the baby is not as cute, much harder to lift, and she spits like a sailor...

In the midst of the chaos, Bubbe remains at the center. When I come in, she grasps my fingers and rubs, as if pulling the warmth of my hands into hers, stirring the blood. Our foreheads tilt together until they meet, and my heart stretches. I’m reminded of the long nights with a cranky baby, when you’re so sleep-deprived that you’re beyond sanity, then just as you contemplate hurling the baby out the window, he looks up and gives you a gurgly smile. Your heart melts and you decide to keep him and nurse him for the eighteenth time on that sore, cracked nipple.

I remember how difficult our son's infancy was for me -- the dark days of sleep deprivation and postpartum depression (chronicled week by week in Waiting to Unfold) -- and I am awestruck at Dvorah's ability to take on this kind of care for someone at the equally-needy other end of life.

This book awakened both compassion and anxiety in me as a reader. Compassion for Dvorah and her Bubbe and her family; anxiety about death and aging, about what indignities or difficulties might come next, about my own loved ones who will some day leave this life. And then every so often I'd come across a passage which just made me smile:

Bubbe looks up at the dancing light, takes in the singing, and says, “I never vould hev believed I’d live long enough to see dis. To be here vit my grendchildren, and great-grendchildren, singing at Chanukah. Who vould believe dis? Ven I get home, I’m going to tell dem about all of you; dey’re not going to believe dis.”

"When I get home." Is Bubbe just confused, does she not remember that Dvorah's house is her home now? Or is she thinking about the going-home which comes at the end of every life, the return to the Mystery none of us can quite imagine? Either way, it touched me.

One of the scenes in the book which has stayed with me the most is an argument between Dvorah and her husband Rabbi David Zaslow. At this moment, she is angry with him for not going downstairs to see Bubbe for almost a week, and now he's getting ready to leave town to lead services for a weekend in another place -- doing the work to which he is called, and also the work which pays the bills, but there's no escaping the fact that it's also work which allows him to leave the house with the dying woman in it.

“You think you’re so holy, but you can’t handle doing something simple. You tell me how meaningful it is to sit on the deathbed of a congregant’s mother, sharing the profound moments with the family, but you don’t sit on the deathbed at home.” I’m pretty sure now that I’m morally superior to him and even if he gets angry and defensive, it will be worth it. I’m on a roll.

“You tell stories of how bonded you were with a girl with a brain tumor, how she played a tape of you singing that echoed through the halls of the hospital—but you don’t bond with Bubbe, because it doesn’t serve your ego.”

I steel myself for a counter-attack, but David just sits down on the bed and shakes his head. “I know,” he says. “It’s true. I don’t know why, but the more intense part of life is what I’m good at. The day-to-day stuff is harder for me.”

This conversation resonated for me for at least two reasons. One is that I remember feeling resentful when our son was an infant and Ethan left the house to go to work three hours away. And the other is that I worry about being "the rabbi" in this scenario. I know there's a risk of my family feeling that I'm giving them short shrift because I'm too busy focusing on the births and deaths and lifecycle events of my congregants to be present to the small dramas of every day at home. It's a testament to Dvorah's writing that I came out of this scene empathizing with both of them.

I'll offer just one more short quote from the book. This is near the end -- of the book, and of Bubbe's life:

It’s silent for a while, then I begin to stroke her arm and speak.“Passover is coming tomorrow, Bubbe. It’s time to go out of Egypt. It’s time. The Red Sea is going to part for you, Bubbe. Moses is going to lead you out of Egypt.” She nods, flicks her eyelids, seems to hear. “It’s okay for you to go now, Bubbe. We love you. We’ll be fine, and we’re going to remember you. Rachel and I are cooking chicken soup with matzo balls, just like you used to. And we’re sewing, like you taught me. We’re going to make popovers from your recipe all during Passover. We’re going to always remember you. We love you, Bubbe. It’s time to let go.”

It's a beautiful passage, and a beautiful modeling of how to grant someone permission to leave this life.

Bringing Bubbe Home is poignant, real, painful, and peaceful. I recommend it -- not only to anyone who's considering bringing a loved one home for end-of-life care, but for anyone who's curious about the end-of-life journey, and anyone who's interested in exploring how we relate to our elders and to the stories which shape us.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers