Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 150

August 26, 2014

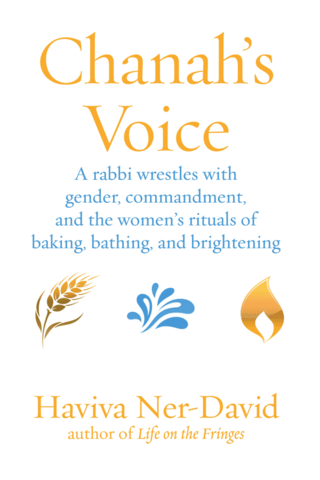

Rabbi Haviva Ner-David on "women's mitzvot" and transcending gender binaries

Last night I went to hear Rabbi Haviva Ner-David speak in Pittsfield at an event co-presented by Congregation Beth Israel (my shul), Knesset Israel, Hevreh, and and Rimon Center for Jewish Spirituality. Here's how we described the event on the flyers:

Last night I went to hear Rabbi Haviva Ner-David speak in Pittsfield at an event co-presented by Congregation Beth Israel (my shul), Knesset Israel, Hevreh, and and Rimon Center for Jewish Spirituality. Here's how we described the event on the flyers:

Rabba Haviva Ner-David is an author, pioneer in Jewish women’s post-denominational thinking, wife, and mother of seven living on Kibbutz Hanaton. She is also a dynamic speaker coming to share the experiences and thinking which led to her latest book: Chana’s Voice: A Rabbi Wrestles with Gender, Commandment, and the Women’s Rituals of Baking, Bathing and Brightening (new from Ben Yehuda Press).

All genders are invited to join us for a talk followed by light refreshments and an opportunity to chat with the author and get books autographed.

I'd actually heard Rabbi Ner-David speak a few years ago at the Mayyim Hayyim mikveh conference Gathering the Waters -- I blogged about her remarks in the post The emerging mikveh movement in Israel. I've been a fan of her work for a long time, ever since I first read Life on the Fringes: A Feminist Journey Toward Traditional Rabbinic Ordination.

She began her remarks by explaining how the process of writing her first memoir led to the spiritual and intellectual inquiry of this second book. "Life on the Fringes was about my childhood growing up Modern Orthodox in New York," she explained, "and my struggles as a feminist with Orthodoxy and tradition, and my decision to study to become a rabbi -- but wanting to get Orthodox rabbinic ordination."

That first book is memoir mixed with halakhic interpretation (Jewish-legal analysis), and one of its main themes is is women's role in tradition. Hair covering, women studying Torah, taking on the obligations which only men are technically obligated to perform -- the "positive time-bound mitzvot." (I've written about those before: Time-bound, 2010.) It occurred to me, as I heard her speak, that the combination of memoir and halakhic interpretation makes me think of midrash aggadah and midrash halakha, the interweaving of narrative and legal interpretation which makes up so much of classical Jewish tradition.

She wrote in Life on the Fringes about tallit and tefillin -- things which (in her Modern Orthodox childhood) men did, and women didn't do. Chanah's Voice explores how she came to recognize that in focusing so strongly on claiming tallit and tefillin for herself, she had neglected the mitzvot which women are traditionally obligated to perform. "I didn't know when I started writing the book what I was going to find," she noted. "But I decided to spend that year struggling with these three mitzvot."

The three mitzvot which are traditionally considered womens' mitzvot are challah (taking challah -- when one bakes a certain amount of bread, one is supposed to take out a portion of the dough and set it aside for the priests, and since today we don't have priests, one sets it aside and burns it), niddah (after menstruation one counts a certain number of days and then immerses in a mikveh before engaging in sexual relations again) and hadlakat ha-ner (lighting shabbat candles.) Together they're known by the acronym ChaNaH, which is a nifty confluence because Chanah is the Biblical figure who is considered to have invented prayer.

"As a feminist, I had a lot of baggage around all three of these [mitzvot]," she admitted, and all the women in the room chuckled.

Where her first book interwove memoir with halakha, this book interweaves memoir with other kinds of Jewish texts -- midrash, Hasidut, and kabbalah. She notes that when she wrote Life on the Fringes, she was caught-up in halakha, a subject which as a woman she wasn't encouraged to study at all. Studying Jewish law was a way of doing what the men did, and she did that for many years. But this book arises out of a different impulse, and not surprisingly draws on different kinds of Jewish texts.

How did the project of Chanah's Voice begin? "My Rosh Chodesh group had disbanded," she recalled, "and around that time, there was a small group of us left who wanted to continue to meet, so we decided to meet twice a month. We were trying to think of a topic on which to focus, so I said, I just decided I want to spend time understanding these three mitzvot; maybe we can do that as a group?"

The book begins with a beautiful short preface about the kabbalistic notion of the breaking of the vessels, a text suggesting that the breakage was intentional because it allows us as humanity to have a role in creating repair. "Revelation of Torah is continual; it's not something given once in one time and one place," she noted. Feminism too is a continual revelation, and is one of the ways we can work together toward creating a redeemed world.

After that preface, Chanah's Voice is divided into three sections, one focusing on each mitzvah. Each section opens with a quote from classical Jewish text which shows what she was struggling with as that section was written -- for instance, "There are three sins for which women die in childbirth: a lack of care with regard to niddah, the separation of challah, and the lighting of the Shabbat lamp." (This is a famous mishna, and oy, is it problematic to the contemporary feminist mindset.)

The challah section of Chanah's Voice, she said, is very much about the idea of the tradition valuing men's work over women's work, and about her journey into shifting that perspective. Challah, baking bread, is definitely considered women's work. (Whereas in that traditional paradigm, laying tefillin is men's work.)

For me one of the most interesting parts of the evening was when she was talking about how taking challah came to feel emblematic of a way of elevating the experience of living in Israel. She read part of the challah section of the book, beginning with a passage about how when she and her husband first made aliyah (emigrated to Israel), she imagined that she was moving to an Israel which would soon be at peace with its Arab neighbors. That peace, in turn, would give Israel spaciousness to work on other important issues like religious pluralism and civil rights. Halevai -- would that it had been so. (Would that it were so even now!) But we all know that that dream has not yet come to pass. What does it mean, what can it mean, to elevate the choice of living in that place at this moment in time?

By way of response, she cited a teaching from Rabbi Yehuda Leib Alter of Ger (also known as the Sfat Emet -- I've posted his teachings here many times before) about why the commandment to take challah comes, in the Torah, right after the story of the spies. The spies returned with the slanderous description of the promised land as a place which devours its inhabitants, and right after that we read the commandment to take challah. How are these related? Challah represents physical sustenance drawn from the earth. When we give a gift of dough to God, we elevate our need for sustenance into a holy act. We respond to the physical world with elevation. But the spies didn't do that:

The sin of the spies represented a failure to cope with the actuality of the physical world. Because they refused to live in the reality of the lower world, they couldn't elevate it with their piety -- instead they disparaged it. They brought the people down with them. The response to the sin of the spies, therefore, is to practice taking challah -- to elevate the world through spiritual acts.

No matter how hopeless it may seem to seek to build the just and righteous society of her dreams in the land of Israel, she resolved to remember the Sfat's Emet point that we can always seek to uplift the reality we're given. She recommitted herself, she said, to "renewed elevation in the face of despair." She decided to prepare enough dough to fulfill the mitzvah of taking challah -- a symbolic reminder of the weekly mission of elevating the physical world and perfecting it. (The mitzvah of taking challah only applies when you bake a certain quantity of bread.) The choice to bake extra bread becomes a holy act, and baking more bread than you need creates an opportunity to give it away, to practice the mitzvah of giving.

Some people might think that as a feminist, and at the time a rabbinical student, I would end up with a more apologetic solution -- that I would look into these womens' mitzvot and say, oh, look at these beautiful mitzvot women were given, why am I running to do tallit and tefillin? But the solution that I came to is that, no, there's beauty in both the "mens' mitzvot," the things we've constructed as a society to call the male side of Judaism, and the more "feminine side." The feminine side has been devalued; we have to find the value in it and lift it up, and offer it to the men and say, look what you've been missing as well.

"I'm in favor of de-gendering mitzvot in general," she noted. In her opinion, there shouldn't be "men's" mitzvot and "women's" mitzvot -- there should be mitzvot, period. "In general I think it's a mistake to obligate certain people based on their gender. People have all kinds of talents and callings, and it seems to me arbitrary to divide it along gender lines."

She told the story of baking challah together with her women's group, and chanting intensely while baking and kneading, and then experiencing an earthquake in Jerusalem while they were doing that. (This is very rare!) And she related that to the story of Korach, in which the earth opens up and swallows the rebels -- who dared to say "we're all equal." (A story with which she acknowledged she has always struggled -- I suspect that every Jewish feminist has.)

Ultimately she made the case that Korach's message was true but it came before its time -- though she also suggested that Korach's problem may have been a hidden belief that he himself should be in power (e.g. he wanted to uplift himself by way of devaluing Moshe), and noted that she doesn't want to uplift women's mitzvot by devaluing men's ones -- she wants to elevate them all.

She spoke beautifully about baking bread with the right kavanot (holy intentions) of connections with the earth and with God. "Bread baking is not just about the end result; the dough and the baker are both changed in the process. Baking challah... has become like a prayer for me," a prayer which she believes has the ability to effect cosmic change. (That made me think of my recent post Seeking peace, and about the idea that in pursuing internal peace we can effect change in God.) "The mitzvah of challah is about recognizing brokenness, and building, without ever destroying."

I appreciate her point that taking on mitzvot which are traditionally understood to be the purview of men is only a partial step toward progress. Taking on tefillin instead of challah, e.g., does nothing to break down the inequality built into the system as we've inherited it. And I resonate strongly with her vision of a world in which men and women together create change in how we relate to gender roles. "The new model," she said, "will be more just, more healthy, more balanced, and therefore more sustainable." It's a very Judy Chicago vision -- "and then both men and women will be gentle, and then both women and men will be strong," etc. (And it's a very Jewish Renewal vision.)

Part of the process of writing this book, she explained, has been a process of coming to question tradition in certain ways -- coming to a place of total egalitarianism and counting women in minyan, for instance. That's a huge shift from the kind of Orthodox feminism which had been home for her previously. "I decided I wasn't willing to wait anymore," she said.

When reading from the section about niddah, she cited the midrash about how at the parting of the Red Sea, even fetuses in their mothers' wombs were able to see the presence of God because their mothers' wombs became as transparent as glass. It's a beautiful piece of poetry, and I liked her interpretation of what it means. Of course the fetuses could see God; "having not yet been influenced by the human world, their connection to God would have been intuitive," she noted.

The real miracle, she said, was not that fetuses could see the presence of God; it was that people who were already living in the human world could "see" God's presence! The era of seeing God's presence is long over. Maybe today we need to think in terms of a different sense. Maybe we need to listen to our own inner voice and trust that it reflects the divine spark within us.

She talked about the problem of male-dominated systems -- the halakhic system; the medical system -- presuming control over women's bodies in order to preserve the patriarchal status quo. What would it take for us to be courageous enough to implement a halakhic solution to the challenges of working with infertility within the niddah paradigm which wouldn't sacrifice women on the altar of "the way things have always been done"?

And she returned to the midrash about the fetuses in their mothers' glass wombs. "The halakha that the rabbis had been interpreting for centuries felt like opaque and impenetrable walls --" providing a safe enclosure, and/but, also suffocating. "I felt able to see through these traditions and walls, perhaps for the first time, to the presence of God."

If Judaism is representing something that's not progressing toward a better world, then it's worth taking a risk to see what will happen if we change things. To listen to Chanah's voice. To not be so afraid. Fear will hold us back from a system that's more just and more holy.

Ultimately, she said, "Torah must be just and good. If not, we are misinterpreting Torah."

Chanah's voice is the silent voice. This is of course how women's voices have so often historically been experienced -- silent; or at least, not heard by men; not meant to be heard by men; not honored by men. (Look at the story of Chanah in I Samuel -- she goes to pray silently for the deepest yearnings of her heart, and the priest rebukes her because he assumes she is drunk. I'll be sharing a new poem about that on Rosh Hashanah, by the way.)

What does it mean to seek to hear the silent voice, to read the white fire within which the black fire is contained? I think this is the whole project of Jewish feminism. I'm really excited to read this book and to delve more deeply into the piece of an answer which R' Ner-David brings to this major question of our time.

August 21, 2014

Seeking peace

Lately I've been working on finding the right balance between paying attention to the world and its many injustices, and cultivating an internal sense of peacefulness and compassion. Against this backdrop, a friend recently shared with me a teaching from her Buddhist practice. According to this way of thinking, if one increases one's own suffering, one adds to the suffering of the universe; if one increases one's own peacefulness, one adds to the peacefulness of the universe.

Lately I've been working on finding the right balance between paying attention to the world and its many injustices, and cultivating an internal sense of peacefulness and compassion. Against this backdrop, a friend recently shared with me a teaching from her Buddhist practice. According to this way of thinking, if one increases one's own suffering, one adds to the suffering of the universe; if one increases one's own peacefulness, one adds to the peacefulness of the universe.

My first reaction, upon hearing this, was that it's a way of justifying contemplative practice. It's easy (for some folks) to knock prayer and contemplative practice by saying that we who engage in prayer and contemplative practice aren't "doing anything" to heal the broken world, and that therefore these spiritual practices are self-centered at best. But in this Buddhist way of thinking, if I can cultivate peace and compassion in my heart, I will add to the overall peace and compassion of the whole cosmos.

This makes some sense to me. If I can cultivate peace and compassion, I'm likelier to relate to others with those qualities instead of with impatience or anger. When I am feeling grounded and mindful and kind, I think I'm a better parent; I suspect I'm also a better partner, rabbi, and friend. That's a small-scale change which might have a ripple effect. But can my acts of meditation and prayer shift the peacefulness in the cosmos in a bigger-picture way? When I work on myself, do I really change the universe?

The Zohar speaks of itaruta d'l'ila and itaruta d'l'tata, "arousal from above" and "arousal from below." Sometimes God pours blessing, love, divine shefa down into creation entirely of God's own accord, and that divinity streaming into creation further awakens us. That's (what the Zohar calls) arousal from above. And other times it is we who initiate the connection -- with our cries and prayers and contemplation, we stimulate the flow of blessing and abundance from on high. That's arousal from below.

Contemplative practices -- meditation, prayer, chant, even the internal work of teshuvah (repentance or return) which is the primary focus of the coming month of Elul and the holidays which follow -- are practices designed to facilitate that arousal from below. When we cultivate peacefulness, or enter into teshuvah, or make a conscious effort to practice kindness, perhaps we awaken parallel qualities on high. At least, that's how the Zohar understands it. Our prayers and meditations can awaken God.

The psalmist teaches "turn from evil and do good; seek shalom/peace and pursue it." (psalm 34:14) We usually understand shalom to mean peace and wholeness in an external sense, between people(s). But I wonder whether we can also read it as an instruction to seek internal peacefulness. Maybe when I cultivate peace within myself, I stimulate the divine flow of more peace into the world. (Or, in the Buddhist framing with which this post began, I add to the net peacefulness of the universe.)

"Seek peace and pursue it" seems at first to be repetitive. If I'm seeking it, surely that means I'm pursuing it too, right? But our sages teach that there are no extraneous words in Torah -- or at least that we can find or make meaning even in the most apparently repetitive of phrases. Ergo there must be a difference between "seeking" peace and "pursuing" it. All well and good, but what might that difference be? Here's one traditional answer, from the collection of midrash called Vayikra Rabbah:

Great is shalom, peace, because about all of the mitzvot in the Torah it is written, “If you happen upon,” “If it should occur,” “If you see,” which implies that if the opportunity to do the mitzvah comes upon you, then you must do it, and if not, you are not bound to do it. But in the case of peace, it is written, Seek peace, and pursue it—seek it in the place where you are, and pursue after it in another place. (Vayikra Rabbah 9:9)

In other words: the other mitzvot ask us to make certain choices when opportunity presents itself. But in the case of peace, we have to be proactive. We have to cultivate peace not only where we are, but also in the places where we haven't been yet (or where peace hasn't been yet). We have to cultivate external peace, and internal peacefulness, precisely in the places -- and the hearts and minds and souls -- which aren't yet peaceful. And when we do this work, we can hope that we awaken God on high to do the same.

On Project Daniel, 3D printing, and hope

Over coffee this morning, my friend Colin showed me a video which I found pretty extraordinary. It's about an endeavor called Project Daniel:

The video isn't new, but it was new to me. Here's how the project's creators describe it:

Just before Thanksgiving 2013, Mick Ebeling returned home from Sudan's Nuba Mountains where he set up what is probably the world's first 3D-printing prosthetic lab and training facility. More to the point of the journey is that Mick managed to give hope and independence back to a kid who, at age 14, had both his arms blown off and considered his life not worth living.

I'd heard about 3D printing, but I'd never actually seen a 3D printer in action, or seen the kinds of things one can create. In my mind, 3D printing was more or less the stuff of science fiction -- Rule 34 by Charles Stross, or Maker Space by KB Spangler. But as this video demonstrates, this technology is very real -- and while I'm sure it's being used for a lot of delightfully silly purposes, it can also be turned to really meaningful forms of service.

Just prior to the trip, the now 16-year-old Daniel was located in a 70,000 person refugee camp in Yida, and, on 11/11/13 , he received version 1 of his left arm. The Daniel Hand enabled him to feed himself for the first time in two years... After Daniel had his own “hand,” with the help of Dr. Tom Catena, the team set about teaching others to print and assemble 3D prostheses. By the time the team returned to their homes in the U.S., the local trainees had successfully printed and fitted another two arms.

I don't want to glorify the "white savior swoops into Africa" narrative. An uncountable number of extraordinary things are done by Africans, in Africa, all the time, though they aren't often reported in American news media. (Take, for instance, the story of William Kamkwamba and his windmill.) But what's remarkable about this story to me isn't Mick Ebeling per se, but the fact of a technology which can create functional prosthetic limbs cheaply, and the look of joy on Daniel's face when he holds a spoon in his new hand and lifts it to his mouth without aid.

It turns out this kind of thing is happening here in the States, too. E-nabling the Future is "a network of passionate volunteers using 3D printing to give the World a 'Helping Hand.'" They design 3D-printable prosthetic limbs and make the designs available under Creative Commons:

We are engineers, artists, makers, students, parents, occupational therapists, prosthetists, garage tinkerers, designers, teachers, creatives, philanthropists, writers and many others – who are devoting our “Free time” to the creation of open source designs for mechanical hand assistive devices that can be downloaded and 3D printed for less than $50 in materials.

Our designs are open source – so that anyone, anywhere – can download and create these hands for people who may need them and so that others can take these designs and improve upon them and once again share with the World in a “Pay it Forward” type of way.

People are using this technology to make new limbs for toddlers, and new hands for veterans. And because the designs are available online as open-source materials, freely available for use and for remix, they're available for anyone who needs them.

At a moment in time when there's so much tragedy and trauma in the world -- Syria, Israel and Gaza, Ferguson, the list goes on and on -- I'm grateful to be reminded that there are people in the world who are giving their time and energy to help others, and to make the world a kinder and more functional place.

August 19, 2014

Poem linked from Slate

Thanks, Slate, for linking to my poem about the "next highest turnpike elevation" sign in What Does This Beloved Road Sign on the Massachusetts Turnpike Actually Mean?

(The poem is one I wrote in 2007, spurred by a prompt which invited the writing of poetry about road signs. It's here: Cross-Country Drive, 1996.)

The Slate piece also taught me a bunch of things about that road sign and about I-90 which I didn't already know. So that's pretty neat.

Dear everyone else: if you're here via that Slate link and wondering just where you've landed, hello and welcome! Check out my About page and/or my list of Favorite Posts. Pull up a chair, stay a while.

August 18, 2014

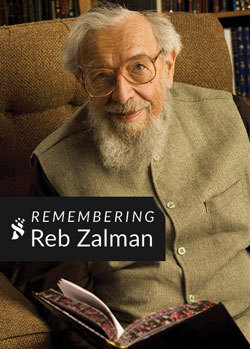

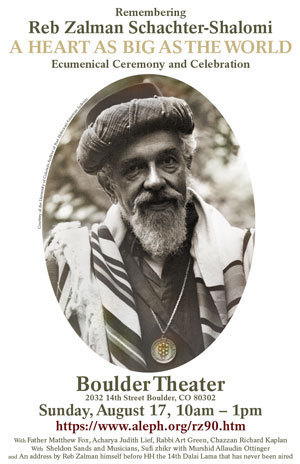

Glimpses of the Remembering Reb Zalman Shabbaton

1.

1.Arriving back at this OMNI gives me a peculiar sort of Brigadoon feeling. Even though I know that my hevre (beloved study-friends) have been geographically scattered since we last met, when I return here and they are here too, it feels as though this place and this community have just been waiting for me to walk in again. The moment I walk in the door, I see people I know and love all over the lobby, chatting and checking in and hanging out, and it feels like home.

I knew that our community would continue long beyond Reb Zalman's time on this plane. I have been certain of this for years -- at least intellectually. And yet there's something in me which needed proof; needed to feel that the connections of our community are as real as they ever were, even though he is gone. Being together, remembering him together, matters so much to me right now.

It is wonderful to be here. And yet I see Rebbetzin Eve (Ilsen) walking through the lobby and it's still hard to believe that Reb Zalman isn't walking beside her. The sweet and the heart-clenching, all in one moment.

2.

The bracelets we're given at registration, which we will need to wear in order to get into the Sunday "A Heart As Big As The World" event at the Boulder theatre, are not flimsy fluorescent-colored plastic like the wristbands I've received in other places. These are made of what feels like recycled paper, nubbly and rough. Then I realize that they are made of handmade paper which contains wildflower seeds. The idea is that we will each take our bracelet home, plant it, and come up with wildflowers. This feels like ALEPH in a nutshell -- sweet, lovely, a little bit orthogonal to the way most people do things, not only eco-conscious but striving to bring more beauty into the world.

3.

Rabbi Arthur Green (or "Reb Art," as he has asked us to call him) begins the weekend with a beautiful teaching about the shema. First he tells us that if his Torah sounds familiar and like Reb Zalman's in many ways, it's because over the decades of their friendship Reb Zalman's Torah became part of him. (After Reb Zalman's earthly deployment ended, Reb Art wrote a beautiful piece about his relationship with Zalman -- My mentor, teacher, dear friend.)

The shema, he points out, isn't a prayer, because it has no atah, no You. It's not spoken to the One, there's no I/Thou interaction. In the shema, everything is One; there's no "us" and "God," there's just the unity of all things. Atah, he notes further, is spelled aleph-tav (the first and last letters of the Hebrew aleph-bet -- what in Greek would be the alpha and omega) and heh, which is the letter of breath and of Shekhinah. Put those together and you get atah, connoting "from beginning to end, enlivened with spirit"!

But the shema has no atah. What it has is unity. And the first line of the shema is sandwiched between the love-prayer of ahavah rabbah / ahavat olam ("a great love," "an eternal love," which our liturgy teaches God has for us), and the love-prayer of the v'ahavta ("And you shall love YHWH your God with all your heart..."). Love leads us to oneness; oneness leads us back to love.

The final paragraph of the shema speaks of tzitzit, the fringes which are intended to remind us of the mitzvot. Reb Art notes that tzitzit is a feminine word, but in the paragraph we chant daily we say the words u'ritem oto, "you shall look upon (masculine) it." It, or perhaps him, not her. (I usually gloss over that when I sing the rendering in English.) So what is the oto on which we're meant to look, if not the tzitzit? His answer is -- God. And he gives us the image of holding up the tzitzit like fringes in a curtain: we're on one side looking at God, and God's on the other side looking at us.

4.

At the beginning of Kabbalat Shabbat, Rebbitzen Eve leads us in an imaginal exercise of filling our innermost hearts with light and then sharing that light with a loved one, and then she kindles the Shabbat lights. She also leads us in a shehecheyanu -- an extraordinary moment of bittersweet celebration. I don't think anyone else would have had the chutzpah to suggest reciting that blessing which thanks God for keeping us alive until this moment. But when Reb Zalman's widow begins the bracha, all of our voices ring out with hers.

Shir Yaakov and Reb Sarah Bracha lead a song-filled Kabbalat Shabbat service, which is exactly the right gentle ramp I needed in order to transition from home to here, from anticipating this weekend to actually being in it, from workweek to sacred time. Shir Yaakov notes, as we begin, that this room in which we are sitting -- the room in which I was ordained! -- is full, so full, of history and memories. That's the starting place from which our prayers will arise.

For me the sweetest parts are singing part of Lecha Dodi to the melody of the bati l'gani niggun which Reb Zalman wrote in memory of Rabbi Yosef Yitzhak Schneersohn, his rebbe; and singing Reb Shlomo's psalm 92 variation ("The whole wide world is waiting, to sing a song of Shabbat..."); and singing some of Shir Yaakov's own melodies which I know from the Shir Yaakov / Romemu soundcloud but had never gotten to daven with him. At the end of the service, after the people who are in active mourning say the mourner's kaddish, Shir Yaakov quietly reads Reb Zalman's translation of mourner's kaddish. Hearing it read aloud in this place in this moment gives me chills.

I am so grateful to be in a room with so many of my hevre, my beloved friends, all of us singing and davening and rejoicing together. Seeing Reb Zalman's sons dancing in the impromptu hora line which snakes through the aisle. Adding my voice to the multipart harmony of our prayer.

5.

And always there are the moments which defy description, which seem banal when written down but are glorious while they're happening. Discovering the small teepee on the hotel grounds (it's always wintertime when we're here for OHALAH; I'd never explored the gardens before); standing in it with friends and declaring it to be our ohel, our tent, which with intention we can transform into a mishkan, a dwelling-place for God; a few precious late evenings sitting with friends in the bank of Adirondack chairs in the night breeze, talking, connecting, laughing, telling stories, just being together. These are gifts beyond price.

6.

Shabbat morning services are delicious. First Reb Arthur (Waskow) weaves a beautiful Torah discussion about the second paragraph of the shema. Then Reb Marcia (Prager) and Hazzan Jack (Kessler) lead a delicious psukei d'zimrah, the songs and psalms of praise designed to open up the heart. I especially love their use of part of "Bright Morning Stars Are Rising" (by Emmylou Harris) as a melodic container for the morning blessings. Also singing Psalm 150 to the tune of Miserlou, a melody which I associate with Pulp Fiction. (It suits the psalm surprisingly well.)

My friend Reb Hannah (Dresner) leads shacharit proper with tremendous sweetness. As I hear her sing, I remember how Reb Zalman used to beam when she led davenen. He loved how she refracts and translates Hasidut into her own feminine idiom. During the Torah service I'm honored with the opportunity to participate in leyning, chanting Torah. I chant, in Hebrew and English, the verses which I translated in the post Cut away the calluses on your heart. I offer a blessing for removing those hard places which obstruct our openheartedness -- and also a blessing for those who may be feeling as though their hearts are already raw, and who need salve and comfort in order to retain the openness with which we want to greet the world.

Reb Nadya and Reb Victor (Gross) lead us in the concluding prayers. Reb Victor tells some stories about Reb Zalman. And Reb Nadya leads us in an amazing Ein Keloheinu ("There Is No One Like God") interspersed with la illaha il'Allah ("there is no God but God.") Reb Zalman's, and by extension Jewish Renewal's, post-triumphalism and deep ecumenism were among the things which first drew my heart and soul here. This juxtaposition of our language for this truth about divinity, and our cousins' language for the same truth, is a beautiful illustration of the deep ecumenism which I so prize.

7.

Sunday morning, 10am, the Boulder Theater. As the crowd gathers in this beautiful art deco building, Reb Zalman's voice is pouring out of the speakers, singing songs and niggunim, while a slide show of his life is cascading across the big screen.

Sunday morning, 10am, the Boulder Theater. As the crowd gathers in this beautiful art deco building, Reb Zalman's voice is pouring out of the speakers, singing songs and niggunim, while a slide show of his life is cascading across the big screen.

Reb Tirzah (Firestone) opens the event with words of welcome, and her presence helps to hold the container in which the whole event unfolds. Father Matthew Fox offers a stunning opening benediction which is also a reflection on Reb Zalman's life and work. Charles Lief, a student of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche and the president of Naropa University where Reb Zalman for years held the World Wisdom Chair, speaks beautifully about Reb Zalman's breadth of knowledge and of passions. (Truly, he says, it was more of a World Wisdom Loveseat, because Rebbitzen Eve was always by his side sharing her wisdom, too.)

Hearing Reb Art (Green) talk about Reb Zalman, his importance, his work, his legacy, is incredible. "When his soul reached heaven," he says (or something along these lines -- I'm paraphrasing), "God did not ask him why he was not Yochanan ben Zakkai, founding a new way of learning in a time of paradigm shift. God did not ask him why he was not the Arizal, master of kabbalistic wisdom. God did not ask him why he was not the Baal Shem Tov, bringing devotional practice to the people. God did not even ask him why he wasn't Reb Zusya, the holy fool!" Because Reb Zalman was all of these and more.

Throughout the event, spoken word reminiscences are interspersed with song. Hearing Hazzan Richard Kaplan sing is incredible, especially when he sings the Baal Shem Tov's Yedid Nefesh and closes his eyes and is visibly transported to other realms. He takes us there with him, and I remember how Reb Zalman used to love to listen to him bringing life to these old and deep Hasidic melodies. His singing becomes the vehicle which carries us aloft.

Singing along with Shir Yaakov and the band as they play his Or Zarua is the first thing that really cracks my heart open. "Light is sown for the righteous, and for the upright of heart, joy" -- surely Reb Zalman sowed seeds of light wherever he went, and now in whatever realm his soul inhabits, surely there is joy. The whole theatre is singing, and I know I am not the only one singing through tears.

That's not the only time that weeping overcomes me. When Rebbitzen Eve gets up with the piano and band and sings "Here's to Life," by Artie Butler, a torch song of love and embracing life to the fullest -- when she walks over toward his big rebbe chair, sitting in a spotlight at the edge of the stage, empty but for the rainbow tallit he designed -- my tears fall again. I cannot begin to imagine the depth of her loss.

When we watch the (never-before-broadcast) video of the address "The Emerging Cosmology," given at the Roundtable Dialogue With Nobel Laureates in Vancouver ten years ago (which explains why His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Bishop Desmond Tutu and other luminaries were seated on stage), I laugh and clutch at my heart. His fur streiml! His joking about looking like someone from Fiddler on the Roof, and then breaking into song! His Star Trek "mind meld" answer to the teenaged girl who asks him a question! And in between all of these sweet things, a powerful teaching about post-triumphalism and organismic thinking and how we need to care for our world.

We close with a Sufi zhikr, a practice in which we remember God through chanting divine names, which breaks my heart open even wider. We are singing three lines, interwoven: bismillah ar-rahman ar-rahim, "in the name of the Compassionate, the Merciful;" ya salaam, ya shalom, may there be peace, God of peace; and a chant which Reb Tirzah tells us she wrote quite recently. "Reb Zalman asked if I would write a niggun when the time was right, to these words," she tells us, and then speaks the words tehi nishmato tzrurah bitzror ha-chayyim and they pierce my heart clean through, because they are a line from El Maleh Rachamim, the prayer we sing only in mourning. "May his soul be bound up in the bonds of eternal life."

Murshid Allaudin Ottinger, a senior dervish of the Sufi Ruhaniat International, leads us in the zhikr. The full band plays: piano, violin which calls out like a human voice in jubilation and in grief, clarinet soaring high, three hand-drummers on different drums. The entire building is packed and we all rise and we sing and the melodic lines braid together. We are hand in hand, or arms around each other, or standing separately but swaying together as we sing: to one side, to the other side, forward. In the name of the One. Peace, God of peace. May his soul be bound up in eternal life. The zhikr builds and builds and I can feel how our singing and our prayer and our memories and our love are lifting Reb Zalman's neshamah higher and higher.

When the event ends my face is wet with tears and my heart is as wide-open as it can be. I am out of words, but I am so grateful, and so full of love.

August 14, 2014

Grief at the deaths of unarmed black men

I've watched with grief and horror this week as stories have emerged of police shooting unarmed black men. Michael Brown was shot by police in Ferguson, Missouri. Ezell Ford was shot by police in Los Angeles. Both of these deaths come on the heels of the death of Eric Garner, strangled by police in New York, only a few weeks ago. Mother Jones reports Four Unarmed Black Men Have Been Killed By Police In The Last Month.

I've been following the #IfTheyGunnedMeDown hashtag on Twitter. "If the police shot me," ask those who tweet with this hashtag, "what photograph of me would the news reports show?" The subtext is often: the news media would choose a photo which makes the victim look "like a thug," as though that justified the killing of an unarmed human being. (See the pair of photos enclosed in this post for an example of what that means.)

I've been reading the essays which smart friends have shared, among them Black kids don't have to be college-bound for their deaths to be tragic. Jasmine Banks writes:

I've been reading the essays which smart friends have shared, among them Black kids don't have to be college-bound for their deaths to be tragic. Jasmine Banks writes:

Let me be clear: Unarmed college hopefuls don't deserve to be shot. Unarmed kids heading to work or trade school don't deserve to be shot. Unarmed kids floundering aimlessly through life don't deserve to be shot. Unarmed kids who have been in trouble—even those who have been nothing but trouble—don't deserve to be shot.

The act of pinning the tragedy of a dead black teen to his potential future success, to his respectability, to his "good"-ness, is done with all the best intentions. But if you read between the lines, aren't we really saying that had he not been on his way to college, there'd be less to mourn?

Also The death of Michael Brown and the search for justice in black America. In that essay, Mychal Denzel Smith writes:

Michael Brown was robbed of his humanity. His future was stolen. His parent’s pride was crushed. His friends’ hearts were broken. His nation’s contempt for black youth has been exposed. A whole generation of young black people are once again confronted with the reality that they are not safe. Black America is left searching for that ever-elusive sense of justice. But what is justice?...

Counting the bodies is draining. With every black life we lose, we end up saying the same things. We plead for our humanity to be recognized. We pray for the lives of our young people. We remind everyone of our history. And then another black person dies.

In my Yom Kippur sermon last year I spoke about the murder of Trayvon Martin. This week I find myself thinking again of Trayvon and of those who grieve him. This week's news seems somehow "worse," as though it were possible to rank this kind of outrage and grief, because this week's killings were committed by police offers. Here is an excerpt from last fall's sermon -- I'm not sure I can say it better now than I did then:

I am the mother of a boy. Someday he will be a teenager. Someday he will walk the streets of an unfamiliar neighborhood in the dark. He might even be wearing a hoodie, or whatever item of clothing teenaged boys think is cool in another twelve or fifteen years. And the odds of someone deciding that he is a threat, and (God forbid) shooting him, are vanishingly slim. Because my son is white.

Because my son is white, if he's pulled over while driving his car, he's not likely to be searched, or to be mistreated by the police. His African American and Latino friends will be three times more likely to be searched and frisked -- at least if things stay the way they are now. Right now, African Americans are almost four times as likely as white Americans to experience the use of force from police. [Source] ...

I am grateful that my son will enjoy the blessings of liberty and autonomy. But I am angry and appalled that other people's children don't have them, simply by virtue of the color of their skin. Every child deserves the privileges I want for my son.

And every parent deserves to live secure in the knowledge that their child can walk the streets safely without being killed. Period.

These deaths are not isolated incidents. They're part of a bigger pattern of systemic racism which is a cancer eating at the heart of my country. In every sphere of life, white Americans are treated differently than Americans of color. (I wrote a little bit about my own process of coming-to-terms with this for Zeek earlier this year -- New Depths in Jewish-Muslim Dialogue: Jewish Privilege.) And this difference in how we are treated, how we are regarded, how we are valued, extends to what assumptions police make about us and how likely they are to shoot.

This is unbearable. This is not the America I want to live in. And as a religious Jew, I'm conscious of the disjunctions between this reality and what Torah teaches. Time and again Torah reminds us not to treat the rich differently than the poor, because that would be a perversion of justice. But what is today's American reality if not precisely that -- breaking down not necessarily along lines of class and wealth (though that happens too) but lines of race and color? We aspire to liberty and justice for all, but black kids and white kids don't experience the same justice, and as a result we don't have the same liberty.

Because American racism is so systemic, it can be difficult to figure out where to begin to approach it. It's woven deep into the fabric of our culture; how shold we begin to go about pulling out those threads? I asked Twitter what I/we might do to make a difference right now, and got some smart suggestions, among them:

support the ACLU in Missouri to help those who were arrested for peaceful protesting & can’t afford their legal costs

contribute to the bail and legal fund for those arrested in Ferguson protesting Michael's killing

listen to, and amplify, black voices speaking about their experience (be prepared to be quiet and learn)

hold our media accountable for telling the real story intead of buying in to predictable and biased narratives (see News reports on Michael Brown's death: how do mourners become a mob?, Ethan Zuckerman)

protest the militarization of police (I'm not sure our tiny rural police department has been part of this trend, but I appreciate the suggestion)

don't forget about this next week when the next sensationalist story hits the front page -- keep pushing for real change

I welcome further suggestions in comments.

My heart goes out to the family of Michael Brown. The family of Ezell Ford. The family of Eric Garner. And all those whose names I do not know. May the Source of Peace bring them comfort along with all who mourn.

Further reading:

Things To Stop Being Distracted By When Another Black Person Gets Murdered By Police, Mia McKenzie

Unarmed Black Men Killed by Law Enforcement, Jenée Desmond-Harris

Do Black Lives Matter In Our Community, Nekima Levy-Pounds

What white people can do about the killing of black men in America, Paul Raushenbush

America Is Not For Black People, Greg Howard

Becoming A White Ally to Black People in the Aftermath of the Michael Brown Murder, Janee Woods

Am I ready?

I've packed white linen skirt, white linen shirt, white kippah. When we welcome the Shabbat bride our whole community will be resplendent in white. I've packed my little jar of glitter so that I can sparkle for Shabbos not only metaphorically but literally.

I've packed Shabbat morning clothes, Shabbat relaxing clothes, something appropriate to wear to the Sunday celebration "A Heart As Big As the World." I've packed swimsuit and coverup, because hey, you never know, I might manage a Shabbos swim.

I've packed tallit and tefillin for Sunday morning, when we'll return to weekday consciousness though not quite yet to our ordinary lives again. I have boarding passes on my phone. In the world of assiyah, action and physicality, I'm about as ready as can be.

In the world of yetzirah, emotion, I'm not so sure. I know that it will be sweet to reconnect in person with my Jewish Renewal community, people who I otherwise wouldn't see again until next winter. But what will it feel like to be together for this reason?

In the world of briyah, intellect, I feel reasonably prepared -- and I also know that I'm going to experience this weekend in ways which transcend intellect and thought. No matter how much I think about this, thought can't prepare me for what lies ahead.

In the world of atzilut, spirit, I hope that the spark of divine light which enlivens my soul will derive joy from reconnecting with so many other sparks, and from coming together in celebration of the neshama klalit, the great soul who lifted us all up.

If you're going to be at the Remembering Reb Zalman weekend, the Shabbaton and/or the Sunday celebration of his life and work, I look forward to seeing you there. To everyone else, I hope your Shabbat is sweet, and thanks for reading, as always.

August 13, 2014

New year's card

DEAR GOD

Spiritual life unfolds

Spiritual life unfolds

in staccato bursts of prayer:

@God thanks, help, please.

Do You miss the measured curves

of pen and ink on cardstock,

our prescribed correspondence

each morning, picture postcard

every afternoon, night's letter

brief but complete? I do too.

But I trust Your mailbox opens

to these ad hoc forms,

praise You for gifts tucked

in the folds of my days:

the cat's rusty purr, scent

of candy-colored Play-Doh,

boy leggy as a flamingo

bouncing on our bed at dawn.

Teach me to listen like You

with endless love. Grant me

another year to practice.

Unfurl my heart's armor.

Comfort, please, the sick;

console those who mourn

open the faucet of blessings.

In return I'll turn

toward You like a sunflower.

Ever grateful for Your ear,

bent to hear

what I need to say.

Here's to the year.

לשנה טובה תכתבו ותחתמו

May you be inscribed for a good and sweet year!

with love,

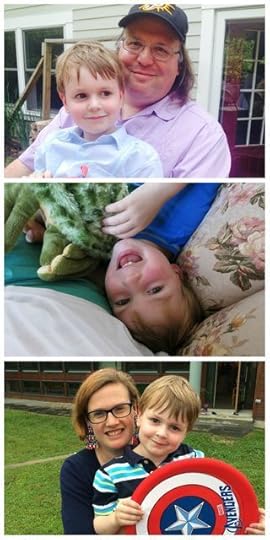

Rachel (Barenblat), Ethan (Zuckerman), and Drew

(For those who are so inclined, here's a link to my archive of new year's card poems...)

This week's portion: cut away the calluses on your heart

At this weekend's Remembering Reb Zalman Shabbaton in Colorado a variety of my friends and colleagues will be collaborating on leading Shabbat davenen. I am humbled and honored to have the chance to leyn Torah on Shabbat morning. I was given the opportunity to choose the handful of verses from parashat Ekev which I wanted to leyn, and I chose Deuteronomy 10:12-19, which translate as follows:

At this weekend's Remembering Reb Zalman Shabbaton in Colorado a variety of my friends and colleagues will be collaborating on leading Shabbat davenen. I am humbled and honored to have the chance to leyn Torah on Shabbat morning. I was given the opportunity to choose the handful of verses from parashat Ekev which I wanted to leyn, and I chose Deuteronomy 10:12-19, which translate as follows:

And now, Israel: what does Adonai your God ask of you?

That with awe of the One, you walk in God's ways, and love God;

that you serve Adonai your God with all your heart and all your soul.

Keep God's connective-commandments and engraved-commandments

which I am giving to you today for your good / to improve your lives.

Behold: the heights of the heavens belong to God; the earth, and all that is upon it.

It was to your ancestors that God was drawn, out of love,

so that you, their descendants, continue to be chosen among all peoples even now.

Cut away, therefore, the calluses on your hearts; stiffen your necks no more.

For Adonai your God is the utmost and the highest (God of God, Lord of Lords.)

God: great, mighty, and awesome, Who doesn't play favorites and takes no bribe,

Who upholds the cause of the fatherless and the widow

And loves the stranger, providing food and clothing.

Just so, you should love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.

I initially chose these verse because I was drawn both to the beginning and to the end of this passage. I liked the exhortation to walk in God's ways and to relate to God both with awe and with love. I liked the exhortation to love the stranger, the Other, for we too have known Otherness and alienation. I imagined that I would offer a blessing, for those who come up for this aliyah, relating to these images. And I still resonate deeply with these verses.

But as I've been rehearsing these lines this week, what's really leapt out at me has been verse 16: "Cut away, therefore, the calluses on your heart, and stiffen your necks no more." Maybe it's standing out for me because of the way the Torah trope (the dots and dashes and symbols which indicate chanting melody) place emphasis on the instruction to cut away -- the melody rises like a waterfall flowing upward before gliding back down again.

And maybe it's resonating for me because I feel lately as though this is precisely what has been happening in me -- the calluses over my heart have been cut away, and my heart is open to the joy and the pain of the world. Every parent rejoicing, and every parent grieving. Every child who laughs, and every child who weeps. Everything that is good and beautiful and right in our world, and everything that is unjust and broken.

The great sage Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote (in his essay "On Prayer") that prayer should be subversive, should shatter the pyramids of domination and cut away the calluses on our hearts. Lately I've been aiming to open up the prayerful opportunities in every moment regardless of whether I'm engaged in liturgical prayer. Even when I'm not reciting formal words of prayer, life offers opportunities to bare my callused heart.

We can choose to make a practice of opening our hearts, of removing the protective scar tissue of anger and mistrust and the need to be right -- or we may find that life does that work for us, stripping away our walls and our calluses through illness, depression, tragedy, or loss. I think it is easier, perhaps gentler, if we do the work ourselves. If we ourselves cut away the calluses we have formed through indifference and callousness.

It is not easy to walk through the world with our calluses removed, with our hearts open to the exultation and the grief. But this is what this passage asks of us. This is what spiritual practice asks of us. When we cut away our defenses, and truly see the anguish of the widow and the orphan, the mother sobbing for her child, the injustices of war, the horrors wrought by illness, we can't help but fulfill the commandment most oft-repeated in Torah, to love the stranger for we were strangers in the land of Egypt.

This week as we prepare to remember our teacher, rebbe, colleague, and friend Rabbi Zalman Meshullam Hiyya Schachter-Shalomi, these verses remind us to keep our hearts open to our mourning and our loss. To keep our hearts open to the sorrows in the news. To actively seek to remove the calluses which would protect us from awareness of suffering. To face that which we don't want to face: in the world, and in ourselves.

This is what Torah asks us to do. Maybe because when we do this, we naturally unlock our store of compassion, which leads us to work to repair what is broken in our world. Maybe because this is part and parcel of relating to God in love and in awe, of walking in God's ways. And maybe because this is a deep spiritual practice through which we do the inner work of transformation, the refining of the soul, for which we are born into this world.

Image source: Circumcision of the Heart by Gwen Meharg.

August 11, 2014

Preparing to remember

On Friday morning I'm going to wake up shortly before 4am (ouch) and drive to the airport for a long-awaited trip to Colorado. I go there every January for the ALEPH smicha (ordination) ceremony and for the conference given by OHALAH, the association of Jewish Renewal clergy. This will be my first summertime trip there.

On Friday morning I'm going to wake up shortly before 4am (ouch) and drive to the airport for a long-awaited trip to Colorado. I go there every January for the ALEPH smicha (ordination) ceremony and for the conference given by OHALAH, the association of Jewish Renewal clergy. This will be my first summertime trip there.

When I planned this trip, my intention was to participate in a celebration of Reb Zalman's 90th birthday. Now it will be a celebration of his extraordinary life and legacy, and an opportunity to reconnect with my beloved Jewish Renewal community as we begin to prepare ourselves for the next era of Jewish Renewal and for whatever comes next.

(For more on Reb Zalman, zichrono livracha / may his memory be a blessing, I direct you to Remembering my rebbe, a post I shared here earlier this summer.)

The weekend is going to be action-packed. On Friday we'll have the opportunity to hear from Rabbi Art Green and to daven with Shir Yaakov, which is always a joy. On Shabbat morning services will be led by a variety of Jewish Renewal folks, including many of my teachers and friends. I'm honored to be participating in Shabbat morning services as well.

On Sunday there will be an event at the Boulder Theater, featuring Father Matthew Fox, Acharya, Judith Lief, Rabbi Art Green, and Chazzan Richard Kaplan, among others. We'll also have an opportunity to experience zhikr with Murshid Allaudin Ottinger and to hear an address from Reb Zalman which was given before His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama and which has never before been aired.

I know it's going to be an extraordinary weekend, full of community and connection, togetherness, laughter and tears, memories and hopes.

You can read all about the weekend, and register for its various components (the Shabbaton, and/or just the Saturday night event, and/or just the Sunday event) at Kol ALEPH: Remembering Reb Zalman Update.

If you can't attend, the event will also be live-streamed, and you can register for that on the Kol ALEPH website, too.

To all who will be joining us in Boulder this weekend: I am looking so forward to being with you and to celebrating Shabbat in the embrace of this extraordinary community. And to all who won't be joining us: I hope you'll consider signing up for the livestream so that you can glimpse a little bit of the memory, celebration, tears, and wonder.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers