Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 146

September 27, 2014

The sweetness of honey; the gates, open

[image error]As a child, I loved being able to drizzle my Rosh Hashanah challah with honey. I remember eating leftover challah toast with honey on the mornings right after the holiday. The golden honey pooling on the rich white bread always seemed deliciously decadent, especially in our Pritikin household. I knew that the honey was a kind of prayer -- "sweet foods for a sweet year." (That's what's behind the custom of dipping apples or challah in honey on Rosh Hashanah.)

But I thought that was a one-time thing. Honey on challah, honey on apples: we ate those on the holiday itself, and then maybe for a few days until the Rosh Hashanah challot were nothing but crumbs. I didn't learn until I was in my mid-thirties that there are customs of continuing to eat honey on one's challah, and praying for a year of sweetness, until Shemini Atzeret.

Shemini Atzeret means "the pause of the eighth day." It's the 8th day of the 7-day festival of Sukkot, the day when (tradition says) after we've lived seven days in our sukkot, God murmurs "this has been so sweet; don't go yet; linger just a little longer?" So we stick around and celebrate one more day of festival together. And though we read during the closing service of Yom Kippur that "the gates (of repentance) are closing," some hold that they remain open until we reach Shemini Atzeret. Hence the tradition of continuing to put honey on our challah all the way until then.

I love the feeling of urgency which comes during the last service of Yom Kippur. The day is almost over; the long day of fasting and prayer and song is almost gone; and what has it gained me? Have I gone deep enough into the liturgy and into my own heart and soul? Is it going to change me? I want to be compassionate and kind to everyone I meet, I want to be mindful -- but have I done the inner work I need to do? The gates are closing, the liturgy tells us. The day is passing. We pray the whole closing service with the doors of the aron kodesh, the holy ark which contains our Torah scrolls, open to remind us that the gates are open and the way to God is open. The sun goes and turns. Let us enter Your gates!

I appreciate that urgency. (I think I need it. Every year when we reach Ne'ilah, that closing service, it lifts me to a place I couldn't have reached otherwise.) But I also appreciate the teaching that the gates remain open during this whole holiday season -- that we can still sweeten our bread with honey, an embodied prayer for a sweet year to come, until Sukkot is drawing to its close. Even after the dramatic end of Yom Kippur with its long and piercing tekiah gedolah, the gate of teshuvah (repentance / return) remains open to us.

When we make teshuvah, we sweeten the year to come. Not because we gain any control over what's ahead, but because we've created a shift in ourselves which will allow us to experience more sweetness. That's the message I hear in the Unetaneh Tokef prayer which we sing on the days of awe each year. Who will be contented, and who will be restless? Who will be healthy, and who will be sick? We can't know what the new year will hold. But when we practice teshuvah, tefilah (prayer), and tzedakah (giving to others), we can ameliorate whatever is to come, because we create change in ourselves. We can't change what will be, but we can change how we experience whatever comes our way.

Of course, teshuvah doesn't happen only during this time of year. Teshuvah can be an every day journey, an every-week journey, an every-month journey. And I believe that God is always waiting with open arms, ready to welcome us with love, any time we turn away from our misdeeds and try to orient ourselves in the right direction again. Our liturgy teaches that "we are loved by unending love," and that's always true, not only during the holidays.

So what does it mean to say that the "gates" are open, or closing, or closed? Maybe the gates are our own. Maybe they are the gates of the season. Once we make it to the end of Sukkot, we will be spiritually worn-out from the intense emotions and intensive holiday journey of this time of year. We will need to close the door on this chapter and move into what's coming. We can't live all year in this state of heightened intensity. We are the ones who close the gates.

The gates which are now open are the gates of our hearts and souls. What do we want to draw forth from ourselves as we move through these gates? When the time comes for us to close the gates on this season, who do we want to have become?

September 25, 2014

Children of Sarah and Hagar (a sermon for Rosh Hashanah Morning 1, 5775)

The story I want to tell you begins on the final day of a retreat for spiritual leaders. We'd been asked to pair up and share a favorite spiritual practice.

My partner and I sat facing each other, our knees almost touching. I told her about my favorite prayer, the modah ani prayer of gratitude. I try to focus on these words first thing in the morning: if not the very first thing which comes to mind when our son wakes me, then at least the first conscious thought I summon into my mind. "I am grateful before You, living and enduring God. You have restored my soul to me. Great is Your faithfulness!" I love the modah ani because it reminds me to cultivate gratitude.

My colleague took this in, nodding. And when it was her turn to speak, she told me that her relationship with the words of formal prayer has shifted and changed over the years. Sometimes the words allow her to speak from her heart; other times the words may feel hollow, or her relationship with the words may feel complicated. (I can relate to all of those.) But the prayer practice which she cherishes most, she told me, is non-verbal. Her most beloved spiritual practice is prostration, which her tradition calls her to do five times a day.

This conversation took place on a Retreat for Jewish and Muslim Emerging Religious Leaders. I particpated in this retreat as a rabbinic student. This summer I went back as an alumna facilitator.

When my new friend told me about her favorite prayer practice, I felt an immediate spark of recognition. Jews prostrate in prayer, too. Though unlike our Muslim cousins, we only do it during the Days of Awe.

Y'all have known me for a while now, so you're probably aware that I love words. As a writer, as a poet, as a liturgist, as a rabbi, as a scholar: words are at the heart of everything I do. And yet the power of our annual moments of prostration, for me, lies not in the words but in the embodied experience.

If you practice yoga, and have relaxed gratefully into child's pose, you've had a flicker of this experience. If you have ever curled into fetal position and clutched yourself close, literally re-membering the position each of us once held in the womb, you've had a flicker of this experience.

But prayerful prostration is something a bit different from each of these. It's a visceral experience of accepting that there is a power in the universe greater than me. Of acknowledging that I am not truly in charge. There is something in the cosmos greater than I am, a force of love and connection which we name God, and in prostration I place myself in the palm of God's hand.

As we sing in Adon Olam:

ּבְיָדֹו אַפְִקיד רּוחִי, ּבְעֵת אִיׁשַן וְאָעִיָרה.

וְעִם רּוחִי ּגְוִּיָתִי, יְיָ לִי וְֹלא אִיָרא.

"Into Your hands I entrust my spirit, When I sleep and when I wake; And with my spirit, my body, too: You are with me, I shall not fear." I love that on our holiest days of the year, the days when we might feel the most wound-up, our tradition reminds us of the profound gift of letting go. And when we do so, we get a glimpse of what our Muslim cousins have the opportunity to feel five times a day.

I find this ancient practice very powerful. And it's always resonant to me that we do this on the first day of Rosh Hashanah: the day when our Torah reading tells the story of Sarah's jealousy and the casting-out of Ishmael and Hagar.

As Jews, we are the spiritual descendants of Abraham through the line of Isaac. According to both Jewish and Muslim traditions, Abraham's other son Ishmael became the progenitor of the Arab nations. In Islam, Ishmael is seen as the ancestor of the prophet Muhammad. Jews and Muslims are cousins, forever related through the brotherhood of those two men who were sons of Abraham.

Of course, Jews and Muslims are descendants not only of Abraham, but also of Sarah and Hagar, the two women who are so central to this story. What changes if we think of ourselves and of the Muslim community not as members of an "Abrahamic" religion but as the children of these two mothers? Does that offer us the possibility of relating to each other in a different way?

Of course, as we heard in today's Torah portion, Sarah and Hagar's relationship was not always easy.

I've always been uncomfortable with the story of Sarah sending her slave and Abraham's other son into the wilderness to die. In my unease, I follow in the footsteps of our sages. Judith Plaskow teaches that our sages were torn between reverence for Sarah as our matriarch, and concern for the powerless, including the slave-woman Hagar. Torah clearly teaches kindness to strangers and to slaves -- and yet Torah also shows us Sarah demanding that Hagar and Ishmael be cast out. What can we do with this tension?

One answer is to cut Sarah some slack. Often, we who make unkind choices do so because we ourselves are suffering in some way.

In this story, Sarah's the one in power. But there are other stories where that's not the case. For instance, to save his own life, Abraham passes her off not once but twice as his sister. He lies about who she is, and Sarah winds up taken into two different foreign harems, powerless to control her own fate.

Torah is a mirror of human experience. It's pretty common for someone who has been oppressed to oppress others in turn. Abraham made choices for Sarah without her consent; in turn, Sarah made choices for Hagar and Ishmael without theirs. One thing we learn from this story is that someone who doesn't have power over her own life may feel the need to assert power over someone else's.

Another thing we learn from this story is that sometimes what we most need appears, if only we have eyes to see. God causes a spring to appear right where Hagar and Ishmael need it -- or perhaps God opens Hagar's eyes to the spring which was already there. When we place ourselves in Hagar's shoes, this becomes a story about miracles and gratitude.

Sarah, Hagar, and Ishmael also appear in Muslim sacred texts. Many stories about these three figures are found in what's called the Isra'iliyyat -- interpretive traditions transmitted during times of close connection between early Muslims and Jews. The way we understand our sacred story has shaped how they understand theirs.

And the way they understand their sacred story has informed how we read ours. How many people here know the story about Abraham smashing the idols in his father's workshop and placing a stick in the biggest idol's hand? Did you know that it isn't in the Torah? It's in our midrashic tradition -- and it's in the Qur'an.

In the collection of classical midrash known as Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, we learn that Ishmael's wives were named Fatima and Ayesha. In Muslim tradition, these are the names of the wives of the prophet Muhammad. That's another sign of how our traditions have influenced each other.

The story we heard today is also one we share with our Muslim cousins. It's an integral part of the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca which each Muslim is expected to make once in a lifetime. In their telling of the story, Hagar, whom they call Hajr, ran back and forth between two hills in search of water. In their version, as in ours, she could not bear to watch her child die. When she called out in her grief, an angel struck the earth with its heel, and at that spot a spring called Zamzam began to flow. As part of the Hajj they reenact her running, and wash hands and feet for prayer in the spring which is said to be the one which appeared and saved Ishmael's life.

Our traditions have so much in common. Not only do we share stories, but both of our traditions are centered around scripture written in a language which for most practitioners is not a native tongue. Not only that: our two sacred languages are cousins. They call God ar-rahman, we call God ha-rachaman, and we're both saying "The Merciful One," using a name which comes from the root rechem which means womb. And that in turn reminds me of the prostration which our traditions have in common, which is so like the fetal position we all knew in the womb.

We can delight in our common ground even as we learn from our differences. In Judaism we feel entirely permitted to grapple with what may seem to us to be flaws or problems in our holy stories. That kind of chutzpahdik interpretation can be a revelation to our Muslim cousins. Meanwhile, our Muslim cousins have things to teach us about the spiritual values of trusting divine providence, of maintaining faith in God, of gracefully submitting to the truth that we're not always in control.

This is going to seem like a non sequitur, but bear with me. Take a moment to notice your body. Focus your attention on your breathing; touch your wrist or neck to feel your heartbeat. Isn't it amazing how your organs work together to keep you alive? Now imagine what it might feel like if your heart stopped speaking to your lungs, or if a clot kept blood from reaching your brain. As a multiple stroke survivor, I can tell you that I didn't feel the blood clots when they happened -- but I noticed their damaging effects.

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi taught that each religion is like an organ in the body of humanity. We need each religion to shine with its own unique strengths. After all, if the heart tried to do the liver's work, the body wouldn't function so well! But we also need each religion to be in community and connection with the others. Because if the heart weren't speaking to the liver, the body couldn't function, either.

All of humanity is part of one whole. And when we mistrust each other, the lines of communication between one faith-tradition and another -- between one organ and another -- become blocked. Our fear of each other is like a clot, blocking the connections that humanity needs most.

There are old wounds between our two religious communities, wounds which may date all the way back to Abraham's expulsion of Hagar and her son. They're certainly exacerbated by the painful last century in the Middle East.

It's easy for both communities to take refuge in triumphalism: for us as Jews to say "our story is the right one because ours was here first," for them as Muslims to say "our story is the right one because it came down as a corrective to yours!" And there are triumphalist voices in both communities -- voices of those for whom religion is a zero-sum game, for whom in order for us to be right, they have to be wrong, whoever "they" are.

But I believe that in this historical moment we are called to shed triumphalism, and to embrace the redemptive potential of affirming that ours is not the only path to holiness. I believe that this era of internet-assisted interconnectedness gives us a historically unique opportunity to see ourselves as part of a greater whole. As Reb Zalman also taught, once humanity became able to see our planet from space, our eyes were opened to our interconnectedness. What hurts "them" hurts "us" also.

If each religious tradition is an organ in the body of humanity, then our fears and anxieties about each other are shrapnel in that body, sources of recurring pain. But what might happen if we committed ourselves to learning about each other? To meeting each other face to face not as strangers but as cousins, descendants of the same complicated clan?

Maybe we would have the experience of looking into our cousins' faces and seeing glimmers of the common ancestors we share. Even if our physical appearances differ, even if our customs of dress differ, even if our languages of prayer differ -- we're part of the same family.

Making these connections can be a challenge in northern Berkshire, where the Muslim community is small and mostly collegiate. But during the coming Jewish year I'm going to bring one of my Muslim colleagues and friends to speak at CBI and to share her wisdom with you. That will be an opportunity to learn about Islam and to teach about Judaism face to face, with open hearts, as I was blessed to be able to do on my retreat this past summer.

For a different kind of learning, on your way out today you can pick up a curated reading list of good books, designed to introduce Muslims to Judaism and to introduce Jews to Islam. (Here it is for those who are reading online:Jewish-Muslim-Reading-List. I welcome other suggestions from readers in comments, too.)

This work of learning and connection is happening in Israel, too. There are courageous Arab and Jewish peacemakers who learn together, visit each others' communities, celebrate each others' lifecycle events and mourn each others' losses. Organizations like the Sulha Peace Project and the Jerusalem Peacemakers draw on Jewish, Christian, and Muslim prophetic voices to bring Jews and Muslims, Israelis and Palestinians, together in the service of building peace.

Building peace together was also the impetus for Choose Life, a joint Jewish-Muslim fast for peace on July 15th of this year. In our tradition, that day was the minor fast day of 17th Tamuz, when we remember the breach in Jerusalem's walls in 586 BCE which led to the Babylonian destruction of the first Temple. In their tradition, that day fell during the fasting month of Ramadan. This Fast for Peace originated with a Jewish settler and a Palestinian activist in the West Bank, and quickly spread to communities around the world.

All that's required is openness... and the willingness to make a connection. It's like how we make hamotzi here on Shabbat mornings: everyone helping to hold up the challah, or touching someone who's helping to hold up the challah, or touching someone who's touching someone, until we're all connected.

Because we are all connected. This summer I was invited into pre-dawn prayer by my Muslim sisters. A new friend offered the Sufi teaching that one should seek with every breath to say a prayer asserting that there is nothing else but God. And I thought of the line from Psalm 150, כֹּל הַנְּשָׁמָה תְּהַלֵּל יָהּ, "let every breath praise You." And I thought of the kabbalistic teaching that אֵין עוֹד מִלבַדוֹ, "there is nothing else but God." I thought: wow, our traditions have this in common. And then we sat together in our pyjamas, singing names of God until the sun had risen.

A few hours later the Jews reciprocated, opening up our prayer space so our Muslim sisters could join us for shacharit, daily morning prayer. Afterward, a friend said to me that while our melodies were unfamiliar, the meanings behind the words made perfect sense, because what we're saying exists in their tradition too.

There's more that connects us than divides us. I believe this is true not only between Jews and Muslims but across almost any difference on this beautiful earth. Across nationalities, across cultures, across borders: there's more that connects us than divides us. Imagine if we all woke up in the morning with the intention of strengthening what connects us, instead of digging in behind what divides us.

I'm not saying we're all the same. Thank God, we're not! Thank God, our world is full of difference and diversity. And Torah teaches that we are all made b'tzelem Elohim, in the divine image. In my understanding, that means that it takes every human being who was, is, and ever will be to make up the reflection of our infinite God. Our differences are essential. And, when you put us all together, we're part of a greater whole, a Unity of which each of us is an integral part.

Our sages teach that today, on Rosh Hashanah, the world is born anew. Or, in another translation, today the world is pregnant with possibility. Today anything is possible.

What different future do we want to dream for the children of Sarah and Hagar, the spiritual descendants of Abraham / Ibrahim?

The opportunity to learn about each other -- to build and strengthen our connections -- to change the shape of humanity -- to see and celebrate how we are connected -- is in our hands.

The angel tells Hagar, "don't be afraid." As I chanted earlier this morning: וַיִּפְקַ֤ח אֱלֹהִים֙ אֶת־עֵינֶ֔יהָ וַתֵּ֖רֶא בְּאֵ֣ר מָ֑יִם וַתֵּ֜לֶךְ וַתְּמַלֵּ֤א אֶת־הַחֵ֨מֶת֙ מַ֔יִם וַתַּ֖שְׁקְ אֶת־הַנָּֽעַר:

"And God opened her eyes and she saw a well full of water. She went and filled her container and gave it to the boy to drink."

This Rosh Hashanah I want to say to you: Don't be afraid. Open your eyes. There's a wellspring of life-giving water right here, within our grasp. And it can sustain not only us, but also our children -- with the promise of a different future, a world of interconnection between the children of Hagar and the children of Sarah.

כֵן יְהִי רַצוֹן: may it be so.

New poem: the story of Chanah

On the first day of Rosh Hashanah, our haftarah reading -- the assigned reading from the later books of the Hebrew scriptures -- is the story of Chanah, from the book of First Samuel. For the last few years I've offered the haftarah as a storyteller telling a story. This year I'm sharing a poem instead. The poem draws substantially on classical midrash about Chanah. I hope it speaks to you.

Chanah Speaks

We didn't marry for love

but Elkanah (whose name

means "God is zealous")

had kind eyes and gentle hands

and I was not afraid.

How he'd learned

the ways of the marriage bed

I never asked.

We came to know each other

and came

to know each other again

and I walked around town

smiling that secret

newlywed smile.

Until the day I bled.

Regret pierced my heart.

But at the mikveh the women said

it can take a few weeks

don't panic, keep trying.

But I bled again.

And again. And then the moon

waxed and waned

and I stayed intact

and our hearts skipped like lambs --

and then I woke to blood.

The women stopped

meeting my gaze

at the mikveh, fearful

of my barren womb.

As if my eye meant harm.

After ten years

Elkanah took another bride.

The Mishna says

he didn't have a choice.

He needed an heir.

And Peninah provided.

Oh, Peninah provided,

child after child after child

with their chubby thighs

and fists wet with drool.

When the time came

to offer sacrifices at Shiloh

Elkanah brought a cow

and when the priests

had carved her up, some

for God and some for them

and the rest for our feast

Elkanah gave one plate to me

and the rest went down the table

to Peninah and her brood.

I couldn't hate those kids.

But there was a void

where my child should be.

Absence gnawed at my heart

and left me in tatters.

Centuries later the sages would say

I was devout in lighting candles

and going to the mikveh

and burning a pinch of dough

before Shabbat, all the things

a Jewish woman's meant to do.

But what kind

of compassionate God

would keep me barren

because He desired my prayers?

Nine years I watched

as Peninah thrashed in labor.

She overflowed with milk

and though I'd married young

I was a dried-up spring.

On the way home from the shuk

Peninah would needle

did you buy a tunic

for your oldest son?

And in the mornings she'd croon

aren't you going to get up

and bathe your boys before school?

And at 3pm, the poisonous murmur

aren't you going to fix

a snack for their return?

And Elkanah would say

Chanah, my love

why are you crying?

Aren't I better to you

than ten sons?

He didn't understand

my emptiness.

That year when we returned to Shiloh

I draped my veil over my face

and whispered to God

What do You want from me?

Please, God (I said)

please, I'll do anything

You know my thoughts

and my most secret heart.

Why did You give me breasts

if I'll never use them

to nurture new life?

Why have You sentenced me

to this slow death?

Jezebel was wicked

and You gave her seventy sons.

You scatter children

in the countryside like seeds

but my soil is barren.

Lend me a son

and I will dedicate him to You!

Eli the priest shamed me,

thought I was drunk

but when I said no, my lord,

I am crying out

before the One Who hears me

he was chastened

and said God grant your prayer.

And Elkanah knew me.

The sages say

more than the calf wants to suckle

the cow yearns to give milk.

More than I yearned for a son

God yearned to grant my desire.

This time Peninah watched

as my belly swelled

like a ripe watermelon

and I relished every hiccup

every kick to the ribs.

When the baby was born

I named him Shmu-el, "I asked God."

When the time came

to go up to Shiloh I refused

and Elkanah understood.

I couldn't bear to give up

the boy who'd rested on my chest

with his limbs frogged up

who had transformed my body

into a receptacle for holiness

-- not yet.

I stored up every memory:

his wobbly footsteps

and first words, his wee handprint

baked into sun-hardened clay

and though I was still nursing

I conceived again

and again, two more sons

and two daughters

no two of them the same.

When Shmuel was weaned

I returned to Shiloh a different woman.

I carried myself now

like someone who has held

a baby on her hip.

Eli didn't recognize me

but I reminded him

I am the one

who prayed silently

and this boy is my prayer

and as I promised

I lend him back to Adonai.

Shmuel was brave

and bright-eyed, staring

at the bustling precincts

-- pilgrims bringing pigeons

and goats, priests

in their bright linen robes --

and he hugged me goodbye

without a fear in the world.

I had thought

I would grieve

when I came home, but

I can still feel him, tethered

forever to my heart.

September 24, 2014

The last #blogElul poem: Return

RETURN (ELUL 29)

RETURN (ELUL 29)

This month is all about return.

Take stock of who you are and start again.

You can always turn over

a new leaf. Nothing's written

in stone, no lock is sealed.

The important thing is to begin.

The habit may seem strange when you begin.

Pausing each night to turn and re-turn

the day's events in memory before they're sealed

by sleep? What's the point of that, again?

But you know your hard drive's written

by your words and deeds, over

and over. Go deep, let the waves wash over

your head. Once you're there, begin

to read the lines you've written

in your book of memory. Return

to where you started from again.

Life imprints the soft wax of your heart, sealed

like a signet ring, sealed

and drying fast. But it's not over

yet. You can try again.

Pick up your pencil and begin.

Only a few days until you'll return

your blue book, and what you've written

is what God will judge. Days written

on your body; your choices sealed

into your skin. Time to return

the library books you've kept over

due, face up to the fine, begin

to think about reading lists again.

Freedom's carved on your tablets again.

Inscribed with God's own hand, written

under your skin. Will you begin

to excavate what's concealed

inside your heart? Over

turn the harsh decree and return

again? On Yom Kippur is sealed

what now is written. Can you get over

your own fears? Begin. Be loved. Return.

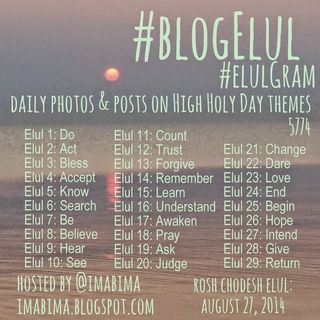

This is the final poem of this year's #blogElul. Whether you've only just started reading, or whether you've been reading all the way along, thank you for sharing this journey.

(I'm already working on revising and polishing these 29 poems, and hope to make them available as a print chapbook before next year's Elul. Stay tuned for more on that.)

May your Days of Awe be awesome, meaningful, and sweet; may you be inscribed for a good year to come. Here's to 5775!

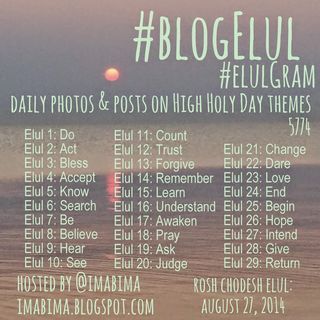

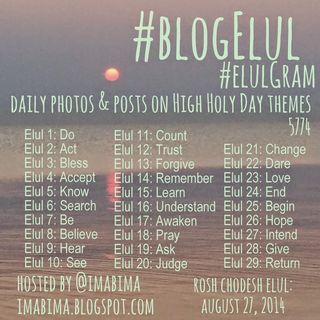

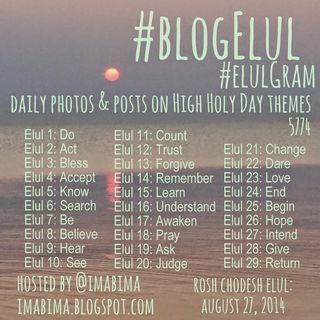

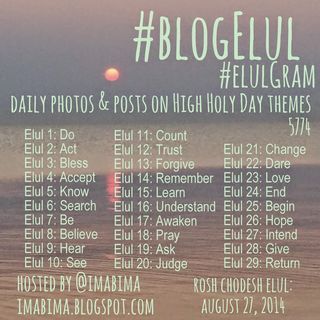

I'm participating again this year in #blogElul, an internet-wide carnival of themed posts aimed at waking the heart and soul before the Days of Awe. (Organized by Ima Bima.) You can read last year's and this year's #blogElul posts via the Elul tag; last year's posts are also available, lightly revised, in the print chapbook Elul Reflections.

September 23, 2014

A poem for #blogElul 28: Give

GIVE (ELUL 28)

GIVE (ELUL 28)

Another chance. Is that so much

to ask? Give me a do-over.

Let me erase these wild formulae

from the blackboard and write

love letters instead. Hand me

that screwdriver; I want to fix

the things I cobbled together

in haste, the hinges between us

hanging broken. I won't waste

this time. Look how time itself

gleams, every moment a dewdrop

beading the finest of spiderwebs.

Every morning when I open my eyes

I'll shout blessings from the deck.

That my soul enlivens this body

still! I won't take it for granted.

I'll tuck a spoon in my pocket

and taste everywhere you take me.

I'll remember to give compliments.

I'll crease cynicism into quarters

like a battered old roadmap

and throw it away. I'll navigate

by whatever coordinates you give.

I'm participating again this year in #blogElul, an internet-wide carnival of themed posts aimed at waking the heart and soul before the Days of Awe. (Organized by Ima Bima.) You can read last year's and this year's #blogElul posts via the Elul tag; last year's posts are also available, lightly revised, in the print chapbook Elul Reflections.

September 22, 2014

A poem for #blogElul 27: Intend

INTEND (ELUL 27)

INTEND (ELUL 27)

And what did I intend, after all?

To uncover beauty everywhere.

To travel even

into the heart of an enemy

and unlock the rusted gate.

To walk beside someone

for a time; to share

a simple sunrise as spectacular

as a nebula unfolding.

To act as though

I were really the person

your starry eyes imagine.

To be a story.

Remembered and retold.

I'm participating again this year in #blogElul, an internet-wide carnival of themed posts aimed at waking the heart and soul before the Days of Awe. (Organized by Ima Bima.) You can read last year's and this year's #blogElul posts via the Elul tag; last year's posts are also available, lightly revised, in the print chapbook Elul Reflections.

September 21, 2014

Visiting those who are gone

My congregation, like many communities, has a custom of holding a short memorial service in our cemetery on the Sunday afternoon just before Rosh Hashanah. It is usually an intimate affair. Those who attend tend to be our oldest members, who frequently have generations of loved ones buried in this hallowed ground. Many of our younger members are transplants to the area (as am I, though after 22 years I have come to feel pretty well rooted here) and don't have graves to visit here. And even if we did have graves to visit, I don't know that most of us would take on this practice.

My congregation, like many communities, has a custom of holding a short memorial service in our cemetery on the Sunday afternoon just before Rosh Hashanah. It is usually an intimate affair. Those who attend tend to be our oldest members, who frequently have generations of loved ones buried in this hallowed ground. Many of our younger members are transplants to the area (as am I, though after 22 years I have come to feel pretty well rooted here) and don't have graves to visit here. And even if we did have graves to visit, I don't know that most of us would take on this practice.

Every time I prepare to lead this service, I think about my maternal grandmother, Alice Epstein z"l, whom we called by the Czech term of endearment Lali. She grew up in Prague, and used to grouse that Americans were peculiar in our reticence to visit cemeteries. In her childhood it was common practice to visit the cemetery on Sundays, perhaps bringing a picnic, and to spend time paying respectful visits to one's loved ones who had left this life.

I think I must have heard that story from her when we visited the new cemetery in Prague together in 1993 along with several other members of my family. ("New" because it was built in 1891 to relieve the overcrowding at the old cemetery, which had been in use since the 1400s. We visited that one too, though more as a historical site than as a place of our own family history.) Where the old cemetery was a crowded jumble of ancient Hebrew-carved stones, I remember the new cemetery as being stately and green, filled with ivy and tall trees and art deco headstones.

I think of that Czech cemetery when I visit the one where I work today, because this one too is tree-lined and beautiful. And I wonder: is it Americans (as opposed to the Czech) who don't make a habit of visiting cemeteries, or is it the younger generation, no matter where in the world we are? ("Younger" in this case meaning younger than my grandparents, of blessed memory, who were born in the early years of the 20th century.) How many of us, in today's world, still live in the towns where our parents or grandparents or great-grandparents are buried?

I think of that Czech cemetery when I visit the one where I work today, because this one too is tree-lined and beautiful. And I wonder: is it Americans (as opposed to the Czech) who don't make a habit of visiting cemeteries, or is it the younger generation, no matter where in the world we are? ("Younger" in this case meaning younger than my grandparents, of blessed memory, who were born in the early years of the 20th century.) How many of us, in today's world, still live in the towns where our parents or grandparents or great-grandparents are buried?

My shul's cemetery is up in the hills just outside of North Adams proper, in the town of Clarksburg. To get there, one drives along route two and then up into the hills. One drives past houses and trees and horses at pasture before arriving at the gates to our cemetery, our "house of life." That's what Jewish cemeteries are traditionally called. The name arose because of the belief that when this incarnation ends, our souls continue to eternal life beneath the wings of Shekhinah. For many people today, maybe the cemetery is a house of life in that it reminds us that we ourselves are still living.

Anyway, our house of life is in a beautiful spot, surrounded by trees whose leaves rustle at this season as they begin to turn orange and red and gold. They'll flame brightly before they brown and fall. There's something especially poignant about holding our cemetery service surrounded by trees which are about to undergo, or are already undergoing, that change. It's so easy to experience the seasons as a metaphor for the cycles of human life.

Anyway, our house of life is in a beautiful spot, surrounded by trees whose leaves rustle at this season as they begin to turn orange and red and gold. They'll flame brightly before they brown and fall. There's something especially poignant about holding our cemetery service surrounded by trees which are about to undergo, or are already undergoing, that change. It's so easy to experience the seasons as a metaphor for the cycles of human life.

Each year on the Sunday before the holidays I join a handful of our members in a semicircle of folding chairs and I lead them in prayer. The service itself is brief: a few prayers, a few poems, some singing which rings out against the headstones and the hills. The memorial prayer which I sing at every funeral. The mourner's kaddish, our prayer which reminds us to offer praise even in the face of death. And then the small crowd disperses to walk among the stones, to trace engraved names with wrinkled fingertips, to place pebbles as markers of our visit and our remembrance.

During this year's service I pointed out that the silent yizkor prayers of remembrance promise that we will engage in acts of tzedakah (righteous giving) in memory of those whom we have lost. I explained the traditional belief that giving tzedakah in remembrance of a loved one can help that loved one's aliyat ha-neshamah, the ascent of their soul to higher and higher levels of the heavens. Even if that image doesn't work for us, or doesn't mesh with what we believe about the afterlife, it's still a beautiful teaching.

During this year's service I pointed out that the silent yizkor prayers of remembrance promise that we will engage in acts of tzedakah (righteous giving) in memory of those whom we have lost. I explained the traditional belief that giving tzedakah in remembrance of a loved one can help that loved one's aliyat ha-neshamah, the ascent of their soul to higher and higher levels of the heavens. Even if that image doesn't work for us, or doesn't mesh with what we believe about the afterlife, it's still a beautiful teaching.

After the service, when we were lingering at our folding chairs, someone asked what I believe about the afterlife. We talked for a while about what I believe -- I offered the image of the droplet of water rejoining the waterfall, the soul returning to its source; I offered my belief that those who have died can hear us when we need to speak to them, at Yizkor services four times a year, or when we visit them in their places of burial -- and how my beliefs fit with some of our tradition's teachings, among them the idea of gilgul ha-nefesh, the "transmigration of souls."

And then I sat for a while with a particular elder congregant, who reminds me every time we meet that when we first met he "engaged me" to officiate at his funeral. I told him, as I always do, that I remember the promise -- and that I'm glad that he hasn't yet cashed in that chit.

There is something awe-inspiring for me about being able to daven these prayers with our oldest members each year, and also with some of the children of our elders who come in remembrance of their parents. Our elders have seen a lot of rabbis come and go. I'm honored that they, along with the rest of my community, have entrusted the care of this holy community to me.

When I wake up on the Sunday before the holidays, there's always a lazy part of me which wishes -- just the slightest bit -- that I could spend this last Sunday of the old year curled up on the couch with a giant mug of coffee, the Sunday Times, and a good football game. It would be nice to relax into a little bit of normalcy and calm before the whirlwind of the Jewish holidays! But I know that when I get to the cemetery, its calm quiet will enliven me. I will remember every funeral over which I have been humbled to preside. I will greet my community's elders with gratitude for their presence and for my own. And for the remainder of the the old year, and well into the new one, I will be glad to have gone.

A poem for #blogElul 25: Begin

BEGIN (ELUL 25)

BEGIN (ELUL 25)

Of course it isn't easy.

You'll wobble on your feet

like an unsteady calf.

Colors will taste different.

Old comforts will be strange.

Everyone you thought you knew

will look unfamiliar

through your remade eyes.

Dreaming, you'll mutter

in the oldest language.

And what kind of person

are you this time around?

Do you take the door

or leap out the window, wear

tweed or stripes or basic black?

Who do you think you are?

After coming through

these golden days

your skin will be tender

and your heart afire.

It's all right to be afraid.

You're not alone; never that.

Look for the messages

you set afloat in bottles

in your former life

drifting and bobbing

across the endless stars

to find you on this shore.

I'm participating again this year in #blogElul, an internet-wide carnival of themed posts aimed at waking the heart and soul before the Days of Awe. (Organized by Ima Bima.) You can read last year's and this year's #blogElul posts via the Elul tag; last year's posts are also available, lightly revised, in the print chapbook Elul Reflections.

Returning in love: short thoughts on Nitzavim-Vayeilech

Here's the brief d'var Torah I offered at yesterday morning's Shabbat service at my shul. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

If you only take one thing away from this morning's Torah reading, let it be this: that teshuvah is a two-partner dance, and that God is always ready to turn to us in love.

This week's Torah portion speaks in terms of blessings and curses. We might call those "good outcomes" and "bad outcomes." We know that our choices come with consequences, and that sometimes our poor choices lead us to unpleasant consequences. And we know that sometimes we receive outcomes we didn't wish for, even when we've chosen as wisely as we could.

Torah teaches that when we consciously choose a life of mitzvot, connective-commandments, blessings will be open to us. This doesn't mean that if we abide by the mitzvot then nothing painful will ever happen to us. But it could mean that if we weave the mitzvot into our daily lives and into our practice, we'll have more resiliency when the painful outcomes happen, as they sometimes do.

And Torah teaches that when we make teshuvah and turn-toward-God, God is always already turning-toward-us in return, with love.

We've all had the experience of hurting someone's feelings, and then feeling reluctant to apologize for fear of how that person might react to seeing us again. People are complicated. Sometimes we respond from a place of reactivity. But the guiding force of the universe isn't like that. When we make teshuvah, says this Torah portion, God responds to us in love.

If you've paid attention to the Torah readings we've been encountering over the course of this whole year, you might feel inclined to argue with that. It's true that in Torah, God does not always seem to respond with love. Personally, I think that one of the things we see in Torah is the children of Israel learning how to be a people, and God learning how to be our God.

Like any new parent, God seems to respond out of anger sometimes. But if we remember that the name God gives to Moshe at the burning bush is Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh, "I Am Becoming What I Am Becoming," maybe that can help us understand God as constantly growing and changing. God is in the very process of growth and change.

Here is one thing I know for sure: ahavat olam, neverending love, is an essential part of God. Perhaps it isn't a coincidence that we read this portion each year as Rosh Hashanah approaches, precisely at the time when we might be getting most anxious about our journey of teshuvah. "Don't worry," the Torah seems to be telling us. "It's going to be okay. God will greet you with love, no matter what."

On the heels of that teaching comes one of my very favorite passages in the whole Torah:

11Surely, this Instruction which I enjoin upon you this day is not too baffling for you, nor is it beyond reach. 12 It is not in the heavens, that you should say, "Who among us can go up to the heavens and get it for us and impart it to us, that we may observe it?" 13 Neither is it beyond the sea, that you should say, "Who among us can cross to the other side of the sea and get it for us and impart it to us, that we may observe it?" 14 No, the thing is very close to you, in your mouth and in your heart, to observe it.

This mitzvah, this connection, this instruction, is not beyond us. It doesn't require us to be someone that we're not. It doesn't demand that we change altogether before we even attempt to take it on. This is a mitzvah which is already sweet in our mouths, already encoded in our beating hearts. Place two fingers on a pulse point and feel for your heartbeat. Lub-dub, lub-dub: you turning toward God, God turning toward you. You reaching out, God reaching back.

Make teshuvah. Turn in the right direction again. Align yourself with your highest dreams and hopes. And you will be received with infinite, neverending love.

A poem for #blogElul 26: Hope

HOPE (ELUL 26)

HOPE (ELUL 26)

For the heat-cracked soil of our hearts

to receive gentle rain.

For the winds which fan our blazes

to still themselves.

For the stains on the cobblestones

to be only pomegranate juice.

For every parent to wake joyful

because their child is safe.

For God to be able at last to stop

rending her garments with grief.

In Jewish tradition it is customary to rend one's garments in mourning when a loved one dies. This poem imagines God mourning every unnecessary human death as a human parent would mourn the loss of a child.

I'm participating again this year in #blogElul, an internet-wide carnival of themed posts aimed at waking the heart and soul before the Days of Awe. (Organized by Ima Bima.) You can read last year's and this year's #blogElul posts via the Elul tag; last year's posts are also available, lightly revised, in the print chapbook Elul Reflections.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers