Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 143

October 29, 2014

The work

This is the work: remembering reasons for gratitude before I even get out of bed. There is always something for which I could be saying thank You.

This is the work: remembering reasons for gratitude before I even get out of bed. There is always something for which I could be saying thank You.

This is the work: balancing brisk ("c'mon, we've got to get out of the house, I'm going to be late") with gentle ("want me to help you with your sneakers?")

This is the work: laughing at the same jokes again and again, because no one has an appetite for repetition like a five-year-old who's just discovered the "interrupting cow."

Noticing where I've made progress in my inner life, and celebrating myself for that. Noticing where I'm bumping again into things I thought I'd figured out, and forgiving myself for that.

Fixing the same meals, singing the same songs, doing the same bedtime routine. Waking myself up to the sweetness cradled in that routine's familiar contours.

Finding blessings in whatever unfolds. Even when the day is boring or grey or I feel as though I'm walking on a treadmill without getting anywhere. Can I turn the treadmill into a meditation labyrinth, where what matters are my conscious foosteps, not the destination?

This is the day that God has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it. It only comes once. Tomorrow will be a new day, filled with new joys and new adventures. Or filled with new sorrows and new challenges. Or all of the above. But whatever it is, it won't be today. I don't want to miss today.

This is the work: setting boundaries even when our son doesn't like them, even when he tells me tearfully "if you say that one more time I won't be your friend!" Letting him know that it's okay to feel what he feels, and that I hear him, and that the rule still stands.

Letting myself know that it's okay to feel what I feel, and that God hears me, even when the world doesn't conform to my every wish any more than it conforms to our son's every wish. Remembering that even on my crankiest days, I am loved unconditionally.

Setting aside expectations so that I can embrace what is, whatever it is. Trying to grow radical acceptance and trust in the sometimes rocky soil of my heart. Watering that soil with prayer. Practicing the mantra of "I love what comes and I love what goes."

Parenthood is -- spiritual life is -- a parade of constant changes. Infancy gives way to toddlerhood, which gives way to childhood. The bitter passes away, and so does the sweet. Maybe for God, every instant of our lives coexists, but we're time-bound. This is the work: this moment, right now.

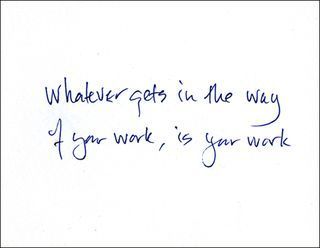

Image: a poetry postcard featuring a quote from Sophie Cabot Black. I learned the phrase slightly differently from my mentor Jason Shinder z"l -- "Whatever gets in the way of the work, is the work."

October 28, 2014

Lesson

After the party

the trees reveal

their elegant bones.

When winds blow

they flirt, naked

branches touching.

The hills unveiled

show off their hips,

put on new clothes.

Now they're professors

in faded purple corduroy

with conifer elbow patches.

They sit zazen

and teach stillness.

How to love what comes

and what goes.

How to appreciate

colors now muted

and light diffuse

soft as wet leaves

cushioning every step.

Bless what's fallen

gracefully yielding

to disintegration.

This poem began its life as the prose post Once the leaves fall, which I posted yesterday.

October 27, 2014

Once the leaves fall

I always forget that once the leaves fall, the trees reveal their elegant bones. So do the mountains. With branches bare, the contours of every hillside come clear. I can see houses, hills, horizon through what used to be a solid wall of leaves.

The hills take on their late-fall garb. Now they're turning a faded purplish-brown with patches of evergreen -- starting from the tops of the mountains, where the leaves are all already down. These colors are comforting and gentle on the eyes.

The skies here have been overcast lately. I tell myself that they are pearlescent and dove-grey rather than gloomy. I think of how beautifully Dale writes about diffuse light, about light during rain, and resolve to savor these variegated clouds.

We're on the last week before the time change. Next Saturday night, while we are sleeping, our nation's clocks will shift backwards an hour. In early mornings, the time change is a mercy; our wakeup time won't be pitch-black anymore. (Not until midwinter, anyway.)

And early evenings...? That's the trade-off. We're heading toward the time of the year when it will be dark by the time we finish Hebrew school on Monday afternoons. Every summer I remember that fall and winter are like this, and I can't quite remember how it's bearable.

But this time of year has its beauty, too. There's one house on Route 7 which I pass on the way home from work every day which is already lighting an electric candle in every window at nightfall. Some mornings now when our son wakes me I get to see the sunrise.

And after twenty-odd years in New England I find that there's comfort in the turn of the seasons, the inevitable change in the mountains' everyday dress, the way that month leads on to month and the year unfolds exactly the way it always does, the way it should.

October 26, 2014

Go into the word and reveal the light: a different reading of Noah

Last week we read parashat Noach -- the Torah portion which tells the story of Noah, the flood, the ark, and the rainbow. One of my favorite teachings about this story turns it into something else entirely. It hinges on the Hebrew word teva, "ark," which can also be understood to mean "word."

When God tells Noah to enter the ark -- so teaches the Baal Shem Tov -- God is also saying, "Enter the word." Go deeply into the word. Which word? The words of prayer. God's instruction to Noah is also an instruction to all of us. We're meant to go deeply into the words of prayer.

Some interpretations continue: just as the ark had three floors or levels, our use of words has different levels: mundane or ordinary speech on the bottom floor, conscious speech on middle floor, and holy speech on the top floor. (I'm not sure this refinement originates with the Baal Shem, but it's lovely.)

The instructions in Torah continue: Noah should make a tzohar, a window, in the ark to let in light. We need to make spaces for light in our words, to ensure that every word we speak is one which brings light to the world. In everything we do, we need to make sure that divinity can shine in.

The grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, Rabbi Moshe Chaim Efraim of Sudlikov (usually known by the title of his best-known book, the Degel Machaneh Efraim), writes -- in one of his short commentaries on Noah and the ark -- that there is always light hidden in the darkness.

Sometimes, the Degel notes, light seems to be covered-over and we can't access it at all. At those times, it's our job to open up the covering and reveal the light. Because light can be found even in the darkness. Maybe especially in the darkness, because darkness is what makes us seek.

October 24, 2014

Cheshvan

Tonight at sundown, when we enter into Shabbat, we will also enter into a new lunar month. On the Jewish calendar, we're about to begin the month of Cheshvan.

Cheshvan is an empty month. A blank slate. An open expanse. It is the only month which contains no Jewish holidays (aside from Shabbat) and no special mitzvot. Some people have the custom of calling this month Mar-Cheshvan, "Bitter Cheshvan," because after so many weeks of feeling ourselves to be in God's presence, we enter into a whole month with no festival opportunities to feel that closeness.

Some rabbis (me included) joke that Mar-Cheshvan is short for "Marvelous Cheshvan," and that Cheshvan is our favorite month precisely because there is nothing in it. After the hard work and the emotional-spiritual rollercoaster of the Days of Awe and Sukkot, a month containing nothing but weekdays and Shabbat feels like a gift. A time to embrace emptiness and quiet. Thank God for Cheshvan; I can't keep up this work-pace anymore!

But I think there's a deeper truth hidden in the "I ♥ Cheshvan" jokes. Our festival cycle has a rhythm, a natural ebb and flow. Times of extroversion and times of introversion; times of intense spiritual work and times of quiet when the aftereffects of that work can reverberate in our hearts and souls. After the spring journey of Pesach and the Omer, we get a quiet period before the summer's fasts and Tisha b'Av and the ramp-up to the Days of Awe. After the fall journey of the Days of Awe and Sukkot, we get a quiet period before the small holidays which stud the wintertime lead us toward spring and Pesach.

(These are northern-hemisphere interpretations; if you live in the global South, the seasonal rhythm is inverted, but the holidays still lead one to the next, and the spiritually-fallow periods are still built-in.)

The quiet time matters too. It's like the silence after the chant, writ large. When a long-anticipated event is over, there can be a let-down. All that time preparing and getting excited, and now it's over; now what? But Cheshvan offers the opportunity to experience the quiet time after the feasts and festivals as a necessary part of the rhythm.

Reb Zalman (may his memory be a blessing) used to speak about the importance of "domesticating" the peak experience -- taking the spiritual highs we can experience on retreat, and using their energy to fuel spiritual practice when we're home again. Coming down from the big fall holiday season is a little bit like coming home from a retreat. We return our focus to all the details of ordinary life. But that doesn't mean that we're no longer in the radiant Presence. We just have to remember how to access that Presence through ordinary living. Avodah b'gashmiut, in Hasidic parlance.

We couldn't live at the intense pace of the Days of Awe and Sukkot all the time. From the practical work of preparing services and sermons and setting up chairs and building sukkahs, to the intellectual work of studying the holidays' texts and liturgies and themes, to the emotional work of noticing what arises in us during the holiday season, to the spiritual work of teshuvah and inner transformation -- there's no way to sustain that level of activity and experience all the time. And that's okay.

The downtime helps us integrate the experience we've just had. Try this metaphor on: the quiet month which comes after all of the festivals is like the morning after a grand and elaborate wedding. The planning and preparation all culminated in a beautiful ceremony and a fabulous party -- and now it's the next day; the first day of the rest of the couple's life; time to integrate the memories and carry them into whatever comes next. Tishri was the wedding. Now it's the morning-after.

The party is finally over. The last guests have gone home. Awaken to your quiet house, a sweet sunrise, coffee filling the room with fragrance. Cup your hands around your mug and look around you. Something new is beginning, right here in this quiet place. Welcome to Cheshvan.

Related: The year as a spiritual practice, 2009

October 23, 2014

An afternoon on Heimaey

For #throwbackthursday: a few photos from 1998, illustrating a short essay of that same vintage. As far as I can recall, this one was never published anywhere.

Lonely Planet is my favorite series of travel guides. The guidebooks focus on exciting places. They're geared to the budget traveler. And I'm charmed by the fact that the series started out as a xeroxed handful of pages about the founders’ journey across Asia. The trick with Lonely Planet, though, is that you have to learn how to interpret their enthusiasm.

Imagine a spectrum of travelers. At one end is the tourist who prefers posh and expensive glamour-travel. At the other end is the traveler whose hiking boots have seen the world and who has the capacity to be entertained by watching fish swim by in a small stream. (No joke; that’s one of the pastimes the Faroe Islands section of our guidebook recommends.) Lonely Planet is geared toward that second archetype.

The Lonely Planet Guide to Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands says of the island of Heimaey, one of the Vestmannaeyjar (Westman Islands, so named after the Irish slaves who unwittingly became their first inhabitants), that visitors normally allow themselves a day or two there, but many wish they’d allowed more. "If you have fine weather (which can include light rain, fog, or overcast skies), three days will allow time to best appreciate the place," the Guide says. We read these words as we were planning a five-day stay in Iceland at the start of our honeymoon. We decided to spend two of those days on Heimaey.

We woke around 5:30 to take a small plane from the tiny domestic Reykjavik airport to the tinier Heimaey one. (Getting up early was no problem, given that the sun had never set.) As we approached the island from the air, everything on its small teardrop shape was visible: at one end, the cross-shaped single airstrip; at the other end, two volcanoes, the harbor, the colorful roofs of Heimaey town.

We shouldered our packs and walked the two kilometers from the airport to the campground on the other side of town; pitched camp; and realized that we’d already covered the length of the island. It was barely eight am. Climbing the island’s active volcano, Eldfell, could only take so long; what were we going to do with two entire days here? This is when the Lonely Planet Scale of Travelers occurred to us, and I chastised myself roundly for not remembering to filter the guidebook’s advice with a little common sense. But there was no changing things; here we were.

So we climbed Eldfell. That was, I must admit, pretty extraordinary. There’s nothing like digging your fingers into the earth's surprisingly hot gravel and having steam come out. From the top we could see the mainland, across a strait of the North Atlantic, covered with a thick icing of glacier. Then we turned around and went back down.

Since we still had time to kill, we headed across the lava fields. Eldfell erupted in 1973, and the eruption lasted for five months; the island grew another third in size from the lava it emitted. Everyone was evacuated, and miraculously the only casualty was a local drug addict who broke into the pharmacy and died of smoke inhalation. (At least, that’s what Lonely Planet says. On factual matters I trust it implicitly.)

Afraid that lava would completely engulf their town and seal off their harbor, the island’s only source of livelihood, the residents sprayed seawater on the encroaching flow. Either the lava ran out of steam, or the water trick worked, because the town and harbor were spared – and an enormous lavafield was created, which is what we were wandering aimlessly across.

My husband led us toward a steep escarpment of tiny lava pebbles and started down to the sea. “I can’t go down that!” I said nervously.

“Sure you can,” he told me. “Just sink in up to your ankles, it’ll hold you steady.” Sure enough, it worked, and after several S-curves we made it down to the shore.

The beach was all black and grey boulders, washed smooth by the sea. And it was completely deserted. On our way down the volcano we’d seen someone else climbing up the other side, but now that we were on the beach there wasn’t a soul besides us. I indulged for a moment in the idea that we were the only people left on the island, in the world.

There were a few eider ducks bobbing in the sea, and we watched them for a while. We curled up on the rocks like seals basking in the sun, and read our books, and drank from our water bottles. Sub-arctic summer isn’t exactly hot, but the boulders sheltered us from the wind, and they soaked up sun. After a while we took off our boots, shook the lava pebbles out of our socks, and rested our bare feet on sun-warm stones.

After a few hours we walked over to the water’s edge and cautiously dipped fingers and toes into the North Atlantic. It was about as cold as I expected. We went back to our stony resting place and rested and read some more.

In memory, the afternoon on the deserted volcanic beach is wrapped in a clear glass shell. It stands apart from the rest of our trip. Elsewhere in Iceland we explored, rented a car, visited museums, climbed rocks; later, in Scotland, we drove nearly a thousand miles, camped in the rain, toured castles, visited distilleries, packed a million things into ten days. On the beach on Heimaey, we were silent: we were still: we listened to the wind and the water, read our books, and watched the occasional arctic tern fly by.

Around six, although the sun hadn’t lowered appreciably in the sky, we decided to head back to town. Our earlier agitation about being trapped on Heimaey had vanished. We walked on a lava-gravel road parallelling the sea, past someone’s large balanced-stone sculptures, and wound up in town by seven. After the silence of our stony beach, even sleepy Heimaey town seemed cluttered.

We dined at the town’s one pizzeria. The menu was all in Icelandic, so we ordered a pizza more or less at random. (It turned out to be covered with tiny North Atlantic shrimp and smoked oysters, which was unexpected.) Then we walked back to our campground for the bright and windy night.

A glimpse of 1977

When I traveled to San Antonio over the summer I brought back a bag of old photographs, which I am slowly digitizing, a few at a time.

When I traveled to San Antonio over the summer I brought back a bag of old photographs, which I am slowly digitizing, a few at a time.

Many of the photos are undated, so I have to guess at when they were taken. This one, though, says "1977" on the back. I'm grateful for that piece of metadata. It tells me that in this picture, I am two going on three, and my mother is only a couple of years older than I am now.

This was taken in the backyard of my childhood home. That house was made of limestone, with a roof made out of red clay tiles in the Spanish style. I remember that gate around our swimming pool, and I remember the little sculpture of a turtle (visible, though blurry, in the bottom right-hand corner) which had been shaped around a pipe, so that water could be made to spray into the pool out of the turtle's open mouth.

Some years later, when I was a decent swimmer and it was safe to take the railing down, my parents replaced the pebbled concrete around the pool with red bricks. And eventually the turtle too went away, though the little fountain remained. I think I insisted on keeping the turtle in the secret hideaway I constructed in the small space between our backyard and the backyard of our next-door neighbors. But none of that had happened yet when this photo was taken.

So many of the experiences I think of as having been formative hadn't happened yet when this photo was taken. At two there's an inconceivable amount of growing and changing ahead. My mother, in contrast, was already recognizably herself when this photo was taken. She had been a mom for years; she had already grown into the adult she intended to be. Of course there were decades of adventures ahead for her, too -- but I think nothing is as extreme as the changes we undergo as kids.

When I look now at photographs of myself as a child with my parents, I'm conscious of being a link in a generational chain. It's fascinating to imagine our son, when he is approaching forty, looking at photographs of me holding him when he was two. What will he see in the expression on my face, the way I look at him, the way we are together? What will he remember of those early years of stubbornly insisting "I do it," climbing and running and falling, playgrounds and sippy cups?

I'm taking advantage of the #throwbackthursday / #tbt meme -- which usually involves posting old photos on Thursdays -- as an opportunity to write short snippets of remembrance, sparked by whatever old photo I find to post. I can't guarantee that I'll do this every Thursday, but I'm enjoying the practice so far.

October 21, 2014

A poem about the name no one can know

SECRET NAME

No one knows the name I was given

by the one who taught me Torah

in my mother's womb. The tap

on my philtrum hid it from me

along with the mysteries of splendor

the secret of mixing fire and water

the spiced air of Eden.

When this deployment is through

and I stand before the Throne

I will not be asked

why I was not Zusya

but did the names I earned

live up to my very first name

which only the angels can speak?

Turning again to Luisa A. Igloria's poetry prompts, I accepted the one for the 21st: Write a poem about your secret name(s).

There's a midrash which holds that an angel teaches each of us all the Torah in the world while we are in the womb, but when we are born, a tap beneath the nose / above the lip makes us forget.

Re: "why I was not Zusya," if you don't know the Hasidic story about Rabbi Zusya on his deathbed, go and read -- it is wonderful.

October 17, 2014

Tools for new beginnings

"This Shabbat is Shabbat Bereshit," I say, "the Shabbat when we begin the cycle of Torah readings again with 'In the beginning...' -- or 'With beginnings...' -- or perhaps 'As God was beginning...'"

I'm speaking aloud to those who've come for Friday morning meditation at my synagogue. My eyes are closed but I know who else is in the room.

"It's a time of new beginnings for us too. What will we need as we enter into this new year?" I let the question float for a moment.

"Imagine that you're standing at the bottom of a flight of stairs," I say, "and at the top there is a door. Walk up the stairs slowly, one by one. When you reach the top, the door opens, and inside is -- you! An older version of you, one who has lived through this year to come and knows what you will need. Invite yourself in. Sit down together. And accept whatever gifts your future self has to offer."

We move into silence.

I am picturing the same room I have pictured before when I have done meditations like this. It is cosy and has windows on all sides; I think it's octagonal, like a room in the turret of an old Victorian. There are rugs and bookshelves and an overstuffed chair or two and probably somewhere there is a cat. On the table between the two chairs is a teapot and a pair of cups, and my older self pours me a cup of tea which warms my hands.

"You're here to get tools for the year to come," she says, and I nod. "Excellent. I was hoping you'd drop by."

The first thing she hands me is a fountain pen. I recognize it: it's Dad's old Mont Blanc, the one I loved so much as a kid, which he gave to me when I went off to college. "I haven't seen this in years," I marvel. My older self smiles. "So this is -- what, writing?"

She nods. "Writing is the best tool we have. Whatever the year brings, write through it. Write it while it's happening. Write what you remember after it's over. Write for yourself, write for an audience, just keep writing."

The second thing is my velvet tefillin bag. "I'm wearing these now," I say, because I am -- here in the sanctuary, where my body is sitting -- though I don't have tefillin on in my imagination.

"I know." She gives me a private little smile. "Consider this a reminder about spiritual practice in general. Davenen, meditation, laying tefillin, talking with Shekhinah in the car -- whatever you can do to remind yourself that you're part of something bigger than your own life and that you're connected with the Holy One of Blessing."

The third thing she hands me is a ball of string. "Tzitzit?" I hazard a guess, because I've been thinking about tzitzit lately, and she grins and shakes her head.

"Remember that exercise where you sit in a circle with a group of people and one person holds one end of a ball of string, and throws it to another, who throws it to another...?"

I nod; of course I do, we have the same memories.

"We're all connected," she continues. "One person tugs on the string, everyone in the circle feels the pull. The string represents your connections. Keep them alive and humming. Reach out to people when you need them. Trust that you're always part of a web of connection. You're never alone."

I place the pen, the tefillin bag, and the string into my purse.

We sip our tea. After a while I say "Sorry, I have to--"

"--have to go, I know," she finishes for me. "See you next time."

I return my attention to the sanctuary where I'm seated. "Whatever gifts you've received, tuck them away so they'll be safe," I say aloud. "Say thank you for them. And walk slowly back down the stairs, back to this place and time, back to where we are."

I wonder what gifts my fellow meditators received. And I resolve to follow my own directions, and to take five minutes to write this down before I forget.

Happy Shabbat Bereshit, everyone. Here's to starting the story anew.

October 16, 2014

String theory

It's a good thing my rabbinic smicha wasn't contingent on my sewing skills. That was the thought which kept going through my head as I struggled with carefully snipping seams (without snipping fabric), placing careful stitches to keep the seams from unravelling further, and then stitching four squares of folded fabric to make reinforced corners. I am not a seamstress, so this pushed the limits of my sewing capabilities. My stitches are far from beautiful or even. But they're functional, and that's what matters. Then I lined up threads in groups of four -- three short, one long -- and pushed them through the reinforced corners. And then I twisted them and tied them.1 By the time I was done, I had made myself a tallit katan.

Next week I'm going to be teaching my fifth-through-seventh-grade class about the mitzvah (connective-commandment) of tzitzit: wearing fringes on our garments. In theory they should already be familiar with this one. They've seen adults wearing tallitot (prayer shawls) in shul. And every Saturday morning, in the third paragraph of the Shema, we pray the verses which instruct us to place fringes on the corners of our garments in order that we might remember the commandments, and the Exodus from Egypt, and our relationship with God. Here's the way I usually sing them (the translation is designed to be singable to the same trope melody as the Hebrew):

And God spoke to Moses saying: speak to the children of Israel and say to them

that they should make tzitzit on the corners of their garments for all time,

and they shall place on the tzitzit a little thread of blue.

And these shall be for you as tzitzit, that you may look upon them,

that you will remember all of the mitzvot of Adonai and you shall do them,

so that you will not go running after the cravings of your heart

or the turnings of your eyes which might take you into places where you should not be!

So that you may remember and do all of My mitzvot, and be holy like your God.

I am Adonai your God,

the One Who brought you out from the land of Egypt to be your God.

I am Adonai your God!

(These verses are part of Jewish daily prayer too, though most of my students have never experienced weekday davenen.) But just because we sing the words all the time -- even given that I sing these particular words in English to make sure they're understood, and hold up my own tzitzit as a visual aid -- that doesn't necessarily mean that my students have ever paid attention, or thought about what the mitzvah means. I want to change that.

Sometimes I offer the translation created by Reb Zalman (may his memory be a blessing.) His rendering is a little bit different from the one with which most of us grew up, and I love it. Like all of his liturgical renderings, it's rooted deep in the Hebrew from which it derives:

ה׳ Who Is said to Moshe

"Speak, telling the Yisrael folks to make tzitzit

on the corners of their garments,

so they will have generations to follow them.

On each tzitzit-tassel let them set a blue thread.

Glance at it and in your seeing

remember all of the other directives of ה׳ who Is,

and act on them!

This way you will not be led astray,

craving to see and want,

and then prostitute yourself for your cravings.

This way you will be mindful to actualize my directions

for becoming dedicated to your God,

to be aware that I AM ה׳ who is your God --

the One who freed you from the oppression

in order to God you.

I am ה׳ your God."

If I were to present these two texts in an adult education class, we would probably have a fascinating conversation: about the two translations, about the Hebrew words behind them, about the mitzvah of tzitzit and how we might understand it as liberal Jews today. But I wanted to give my ten-through-twelve-year-olds a different relationship with the words, something more experiential.

It would be neat to teach the kids how to tie tzitzit, was my first thought. That way if we ever want to make tallitot with the kids who are becoming bar or bat mitzvah, they could tie their own fringes on the edges of their decorated cloth. But then I realized that teaching them to tie tzitzit for that purpose was probably premature. Most of the kids in this mixed-age-group class won't be ascending to that lifecycle event this year, and a tallit is only worn by those of bar or bat mitzvah age or older.

It would be neat to teach the kids how to tie tzitzit, was my first thought. That way if we ever want to make tallitot with the kids who are becoming bar or bat mitzvah, they could tie their own fringes on the edges of their decorated cloth. But then I realized that teaching them to tie tzitzit for that purpose was probably premature. Most of the kids in this mixed-age-group class won't be ascending to that lifecycle event this year, and a tallit is only worn by those of bar or bat mitzvah age or older.

And then I thought: hey, there's another way to fulfill this mitzvah! The variant with which most liberal Jews are familiar is the fringed prayer shawl called a tallit (or tallis -- one is Sefardic / modern Hebrew pronunciation, the other is Ashkenazic pronunciation, but they're the same word.) Tallitot come in a variety of styles and shapes. (I myself own several. My mother has been known to say that one can't have too many shoes; my variation on that theme is that one can't have too many tallitot!) But there's another way to wear fringes: on a tallit katan ("little tallit), a fringed undergarment, which unlike the tallit gadol is worn all day long.

And also unlike a tallit gadol ("big tallit"), a tallit katan can be worn before one comes of age. In some communities boys begin wearing them at the age of three. By that metric, my group of ten-to-twelve-year-olds is well overdue! In Orthodox settings, of course, the tallit katan is worn only by boys and men. (In that same paradigm, the tallit gadol is worn only by men, too.) But in the liberal Jewish world I inhabit, people of all genders can wear tallit gadol for prayer... and there are people of all genders who have taken on the mitzvah of wearing fringes all day every day, as well.

I remembered that Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg had written something about how to make a tallit katan for a woman's body, so I dug up her instructions. Before I made them with the kids, I wanted to make my own, first. I needed to do it before I asked them to do it, both so that I would be a more effective help to them in the nitty-gritty of the stitching and tying, and also so that I wouldn't be asking them to do something I hadn't myself been willing to do. Because I didn't want the journey to end with tying the knots. Making the tallit katan would be part one of the project. Part two would be wearing it throughout at least one day in the coming week, and then reporting back to the class about how it had felt to wear this palpable reminder of Jewishness, of the mitzvot, and of God all day long.

Of course, wearing visible fringes can be chutzpahdik. In some religious settings, if I were wearing fringes, someone might stop me and challenge my my entitlement to take on the mitzvah because I am female. In some secular settings, someone might stop me and say "what are those?" because they've never seen such a thing in their life. (I've had both of those experiences while wearing a kippah.) I don't want to give my kids an assignment which could lead to them feeling ostracized or uncomfortably weird, or perhaps even being bullied. So I did a bit of studying and confirmed that wearing fringes doesn't necessarily have to be a visible act. (Granted, many authorities will argue that we ought to let our fringes hang out, but there are also interpretations which hold that tallit katan represents one's inner relationship with God and therefore can be kept private.)

There are people who keep tzitzit tucked away. Certainly if one's safety would be compromised by wearing this visible sign of Jewishness, then it's okay to conceal it. As far as I'm concerned, that includes emotional safety as well as physical safety. Each of my students will make their own decision about what feels right and comfortable for them. I suspect that they will choose to wear their fringes inside their clothes, and that's okay. It's hard enough being different when you're an adolescent, and when you're one of only a handful of Jewish kids in your school, the otherness can be challenging even without a visible reminder of difference. But even if they wear the fringes in a hidden way, they'll be reminded of them as they go about their day, and I think that will be an interesting experience in all four worlds -- physical, emotional, intellectual, spiritual.

At least, that was my theory. Would it be borne out in practice? There was only one way to find out. And I would find out along with them by wearing tallit katan one day, too -- though of course as The Local Rabbi in a smalltown community, I'm accustomed to being visible as a Jew, so letting my fringes fly didn't seem as scary to me as it might to them. Still, I was excited to explore this new experience. How might wearing fringes feel different from, and also similar to, wearing a kippah? Would it feel different if I made a point of entering into secular spaces (the grocery store, e.g., or the town coffee shop) than it would if I were only walking around the shul? Would tzitzit feel different from a kippah in those non-Jewish spaces? Would I find myself explaining and teaching more than usual? Would that be fun for me, or frustrating, or both?

I learned from Rabbi Marcia Prager the following rule of thumb for exploring a new practice: doing it once is an experiment; doing it a second time is a way to test the experience one had the first time; and doing it a third time is a commitment to continue with the practice. She offered that teaching in the context of a conversation about adults trying on new Jewish practices, and I like her rubric. For kids, I think there's even more flexibility. Especially in the years leading up to bar or bat mitzvah, I want our kids to be thinking about what Judaism means to them and experimenting with different forms of Jewish practice. I think this tzitzit experiment is a good way for my students to live out one of the core values of Reform Judaism: making informed choices bout one's own Jewish practice.

(And, of course, any decision one makes at the age of ten, eleven, or twelve can and should be revisited over the course of one's life! But I like the idea of empowering my students to learn about a mitzvah and to have a direct experience of that mitzvah, even if their decision-making at this age isn't binding for life.)

I don't think that wearing tallit katan is something my students will take on as a daily practice. I don't think it's something I'm going to take on, either. But it's a piece of Jewish practice I have long wanted to try out. And I know that many mitzvot operate on an experiential level more than on an intellectual one. Intellectually I can tell you why it's nice to light Shabbat candles; experientially, the feeling I have while lighting them far transcends that intellectual explanation. (I've written about that before: To Do is To Understand.) So I'm open to the possibility that wearing tzitzit all day will be a transformative experience in ways I don't intellectually expect beforehand.

In any event, even if my students don't wear their tzitzit again after their one-day experiment, I imagine that the embodied experience of tying them and wearing them for a day will be more memorable than any lesson or lecture I could offer. And I am already glad to have given my fingers the experience of tying these holy knots, this metaphysical string-around-the-finger, meant to remind me of connection with the Holy One of Blessing.

1. How did I tie them? There are many different methods for tying tzitzit. (Here are a few of them.) Next time I have the chance, I aspire to learn Reb Zalman's method, which features both white threads and tchelet (blue threads) and knots instead of merely twists. But for my first set of tzitzit, and for this class project, I'm using a simple and fairly standard Ashkenazic method as outlined in the First Jewish Catalogue. You can see that technique illustrated in the image which accompanies this post. In every variation I know of, the strings and knots and windings are given meaning; often the number of twists is correlated to the phrase Adonai Echad, "God is One," in gematria, Hebrew letter-math.↩

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers